Chapter 5

Eggs and Baskets

IN THIS CHAPTER

Building a strategy for diversification

Building a strategy for diversification

Selecting a variety of shares

Selecting a variety of shares

Managing a balanced portfolio

Managing a balanced portfolio

Relying on managed funds

Relying on managed funds

Investing overseas with managed funds

Investing overseas with managed funds

Looking at some non-traditional options

Looking at some non-traditional options

Diversification means using your investment money to buy different assets. Your goal in diversifying is to benefit from the performance of different assets that are usually not synchronised. If shares, for example, are performing poorly, property or bonds may be performing well. You want to include one or both of these in your portfolio in order to diversify across a range of investment options. You also want to diversify within an asset class. Say you already own mining shares — if you then buy a bank stock, a portion of your portfolio isn’t dependent on commodity prices for growth. The aim of diversification is to ensure that, at any time, part if not all of your investment portfolio is performing well.

These days, an Australian investor’s portfolio may contain any of the following:

- Australian shares, property and bonds

- Foreign shares, property and bonds

- Managed funds

- Hybrid securities

- Exchange-traded funds (ETFs)

- Listed investment companies and trusts (LICs and LITs)

- Warrants, options and derivatives

Keep in mind that diversification is a good strategy for all types of investing. If you think of diversification in terms of the adage about eggs and baskets, then more baskets than ever before exist to accommodate your precious eggs. In this book, I talk mainly about diversification within a single asset class, shares. In this chapter I cover risk versus return, growth and value stocks, investing overseas, using managed funds and considering alternative options such as hedge funds, commodities and collectables.

Spreading the Risk

Diversification is an essential strategy for protecting your investments over the long term. The second share you buy diversifies your portfolio, at least a little. Understanding how diversification works is a necessary step in acquiring a balanced portfolio. Three levels of diversification exist:

- You can own different asset classes, such as shares, government bonds and property.

- You can acquire different investments within one asset class, such as owning shares in BHP, CSL, Afterpay, Australian Agricultural Company and Woolworths.

- You can use geographical diversification, such as making an investment in overseas assets.

As an Australian investor, you can choose from about 2,200 stocks listed on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX), which allows you to put together a highly diversified portfolio. You can put together a portfolio that includes higher risk, higher reward opportunities, as well as conservative investments. You can place a small proportion of your total investment funds in higher risk speculative shares — perhaps 5 to 10 per cent, depending on your appetite for risk. (Refer to Chapter 4 if you need help in quantifying just what your risk level is.) However, high-risk investments need good research to ensure that those investments are more of a calculated risk rather than a wild stab in the dark.

Unfortunately, Australian investors have a poor record with diversification when buying shares. A total of 35 per cent of Australian adults — or 6.6 million people — own listed investments outright, according to the ASX Australian Investor Study for 2020. Of course, many more people own listed investments indirectly, through their superannuation accounts.

The likelihood of share ownership increases with age. In 2020, only 40 per cent of ‘next generation’ investors (those aged 18 to 24) hold domestic shares directly, compared to 62 per cent among ‘wealth accumulators’ (25 to 59 years) and 84 per cent among retirees (60+ years).

However, adequate diversification remains a problem. In the 2017 ASX Australian Investor Study, 46 per cent of investors said they had a diversified portfolio, yet on average, they owned only 2.7 investment products. In 2020, 54 per cent believed their portfolio was diversified. Of these, however, 58 per cent were only invested in one to two products, with the average holding 2.6 investment products. Roughly only 5 per cent held six or more investment products. Investors who believe they have diversified portfolios are significantly more likely to hold ETFs, international direct shares, LICs and managed funds, all of which help a lot with their portfolio diversification.

The unlisted property sector collapsed at the start of the 1990s, as regulators were forced to impose a freeze on every unlisted property trust in the country. The sector slowly returned to favour, only to blow up again in the GFC. Once again, many unlisted property structures were frozen, as they struggled with excessive debt, and some were forced to cease distributions. And once again, the liquidity risks inherent in having investment vehicles that offered ready redemptions despite their underlying assets being illiquid made themselves felt. Structures were cleaned up following the GFC slump, and unlisted property recovered its place in a portfolio. Over the five years to June 2019, as interest rates plumbed new lows, Australian unlisted property generated 21.6 per cent a year for investors, according to global index provider MSCI and the Property Council of Australia (PCA).

Table 5-1 shows the historical total returns (meaning income is included) from different asset classes available to an Australian investor between 1990 and 2020. Each of these asset classes has enjoyed at least one year in which it was the best performer — even cash, in 1990. A portfolio that was wholly invested in US shares would have been the best performer, on average, followed by Australian and international listed property. (However, the US shares investment would also have been the most volatile, and had six negative years.) Australian shares delivered 10 per cent a year, with five losing years. On average, unhedged international shares — taking full ‘currency risk’ (refer to Chapter 4) — beat international shares hedged into A$.

At the other end of the risk–return scale, cash isn’t capable of consistently generating the return of a growth asset like shares. However, cash never returns a loss.

TABLE 5-1 Asset Class Returns, 1990–2020

Australian Shares |

International Shares |

International Shares (Hedged)1 |

US Shares |

Australian Bonds |

International Bonds (Hedged)2 |

Cash |

Australian Listed Property |

International Listed Property3 |

|

1990 |

4.1 |

1.9 |

5.3 |

11.2 |

17.8 |

13.1 |

18.5 |

15.2 |

|

1991 |

5.9 |

–2.0 |

–5.8 |

10.8 |

22.4 |

15.3 |

13.5 |

7.7 |

–15.9 |

1992 |

13.0 |

7.1 |

–3.0 |

16.5 |

22.0 |

15.8 |

9.0 |

14.7 |

6.9 |

1993 |

8.7 |

31.8 |

17.3 |

27.9 |

13.9 |

14.7 |

5.9 |

17.1 |

28.3 |

1994 |

15.5 |

0.0 |

6.7 |

–7.8 |

–1.1 |

2.1 |

4.9 |

9.8 |

8.4 |

1995 |

6.4 |

14.2 |

3.7 |

29.9 |

11.9 |

13.1 |

7.1 |

7.9 |

7.5 |

1996 |

14.3 |

6.7 |

27.7 |

13.5 |

9.5 |

11.2 |

7.8 |

3.6 |

2.4 |

1997 |

26.8 |

28.6 |

26.0 |

41.5 |

16.8 |

12.1 |

6.8 |

28.5 |

35.7 |

1998 |

1.0 |

42.2 |

22.1 |

57.5 |

10.9 |

11.0 |

5.1 |

10.0 |

25.0 |

1999 |

14.1 |

8.2 |

15.9 |

14.9 |

3.3 |

5.5 |

5.0 |

4.3 |

–6.8 |

2000 |

16.8 |

23.8 |

12.6 |

18.2 |

6.2 |

5.0 |

5.6 |

12.1 |

14.1 |

2001 |

8.8 |

–6.0 |

–16.0 |

0.6 |

7.4 |

9.0 |

6.1 |

14.1 |

38.2 |

2002 |

–4.5 |

–23.5 |

–19.3 |

–25.8 |

6.2 |

8.0 |

4.7 |

15.5 |

7.5 |

2003 |

–1.1 |

–18.5 |

–6.2 |

–16.1 |

9.8 |

12.2 |

5.0 |

12.1 |

–5.2 |

2004 |

22.4 |

19.4 |

20.2 |

14.7 |

2.3 |

3.5 |

5.3 |

17.2 |

28.7 |

2005 |

24.7 |

0.1 |

9.8 |

–2.8 |

7.8 |

12.3 |

5.6 |

18.1 |

21.2 |

2006 |

24.2 |

19.9 |

15.0 |

11.5 |

3.4 |

1.2 |

5.8 |

18.0 |

24.2 |

2007 |

30.3 |

7.8 |

21.4 |

5.6 |

4.0 |

5.2 |

6.4 |

25.9 |

3.0 |

2008 |

–12.1 |

–21.3 |

–15.7 |

–23.2 |

4.4 |

8.6 |

7.3 |

–36.3 |

–28.6 |

2009 |

–22.1 |

–16.3 |

–26.6 |

–12.4 |

10.8 |

11.5 |

5.5 |

–42.3 |

–31.2 |

2010 |

13.8 |

5.2 |

11.5 |

9.5 |

7.9 |

9.3 |

3.9 |

20.4 |

31.3 |

2011 |

12.2 |

2.7 |

22.3 |

3.1 |

5.5 |

5.7 |

5.0 |

5.8 |

9.2 |

2012 |

–7.0 |

–0.5 |

–2.1 |

10.1 |

12.4 |

11.9 |

4.7 |

11.0 |

7.5 |

2013 |

20.7 |

33.1 |

21.3 |

35.0 |

2.8 |

4.4 |

3.3 |

24.2 |

24.3 |

2014 |

17.6 |

20.4 |

21.9 |

20.8 |

6.1 |

7.2 |

2.7 |

11.1 |

11.8 |

2015 |

5.7 |

25.2 |

8.5 |

31.9 |

5.6 |

6.3 |

2.6 |

20.3 |

23.1 |

2016 |

2.0 |

0.4 |

–2.7 |

7.3 |

7.0 |

10.8 |

2.2 |

24.6 |

20.4 |

2017 |

13.1 |

14.7 |

18.9 |

14.4 |

0.2 |

–1.0 |

1.8 |

–6.3 |

–4.8 |

2018 |

13.7 |

15.4 |

10.8 |

18.7 |

3.1 |

2.5 |

1.8 |

13.0 |

9.0 |

2019 |

11.0 |

11.9 |

6.6 |

16.3 |

9.6 |

7.0 |

2.0 |

19.3 |

13.5 |

Average |

10.0 |

8.4 |

7.6 |

11.8 |

8.3 |

8.5 |

5.7 |

10.6 |

10.6 |

Best |

30.3 (3) |

42.2 (2) |

27.7 (5) |

57.5 (6) |

22.4 (3) |

15.8 (3) |

18.5 (1) |

28.5 (3) |

38.2 (4) |

Worst |

–22.1 (2) |

–23.5 (3) |

–26.6 (4) |

–25.8 (3) |

–1.1 (2) |

–1.0 (2) |

1.8 (7) |

–42.3 (3) |

–31.2 (4) |

(X) denotes the number of times each asset class was the best/worst performer during a financial year ending between 1990 and 2019. Source: Andex Charts Pty Ltd. Notes: 1. MSCI World ex-Australia Net Total Return Index (Local Currency) – represents a continuously hedged portfolio without any impact from foreign exchange fluctuations. 2. Index prior to 30 June 2008 is the Citigroup World Government Bond Index AUD hedged, from 30 June 2008 the index is the Bloomberg Barclays Global Treasury Index in $A (Hedged). 3. Prior to 1 May 2013, index is the UBS Global Real Estate Investors Index ex-Australia with net dividends reinvested. From May 2013 the index is the FTSE EPRA/NAREIT Developed ex AUS Rental Index with net dividends reinvested. Past performance is not an indicator of future performance. |

|||||||||

Source: Andex Charts

Building a Portfolio

Before you start buying shares, decide your level of risk, what income you want from shares and your time frame for investing. With a well-diversified portfolio and a medium- to long-term horizon — at least five to ten years — you’re giving your sharemarket investment the best chance to come out ahead of the other asset classes. Choosing your stocks well is the hard part. You need to follow a logical method in deciding on the stocks you buy.

Professional investors who are active managers of a share portfolio (those who try to add value to the portfolio by choosing stocks that can outperform the market) are usually either growth-oriented or value-oriented. Growth investors loved the tech boom of 1999 to 2000 because it briefly fulfilled their wildest dreams. Value investors hated it because the market paid no attention to their carefully chosen bargains. The market of the value investors’ dreams was the one that came about after the market had halved, from March 2009 onward.

Buying growth stocks

Growth stocks are shares with earnings that increase faster than the growth rate of the economy. They have high earnings, a low dividend yield — if they have a dividend at all, because these companies usually reinvest their earnings into product research and expansion. When you buy a growth stock, you’re usually relying solely on capital gain for the return on your investment. They usually have innovative products, a business model that is able to ‘disrupt’ the incumbent companies in that field, and a large (and expanding) market opportunity.

Over the latter part of the 2010s, as growth investors took the upper hand, a new generation of market darlings began to command P/E multiples of 40, 70 and even 100 times forecast earnings. (The general rule for P/E multiples was traditionally that a value of 10 or lower was cheap and 20 or above was expensive — see Chapter 7 for more information.) This group was led by the ASX’s cohort of technology stars, based around WiseTech Global, Appen, Altium, Xero and Afterpay (then known as Afterpay Touch). Construction software company Aconex was also a fully paid-up member, until it was bought by Oracle for $1.6 billion in early 2018; data centre owner operator NEXT DC was also one, as were specialist dairy company A2 Milk Company and Domino’s Pizza.

Value investors could not stomach paying what to them were ridiculous P/Es for these stocks. Afterpay did not even own a P/E, because it hadn’t made a net profit (and still hasn’t — analysts don’t expect the company to make a net profit until 2022). Xero, at $84.70 in May 2020, was priced at 4,381 historical earnings (it earned 1.9 cents a share in FY20) and at 335 times forward earnings (consensus among analysts is that it will earn 25.3 cents a share in FY21). Glumly, value investors watched the growth superstars rise ever-higher, made worse by the fact that not owning them pummelled the value managers’ relative performance figures.

Prior to the COVID-19 crisis, high-growth companies (defined as those showing EPS growth above 20 per cent), were trading at forward P/Es at well over twice the market, and about 60 per cent above their international peers, according to broker Goldman Sachs. The ASX tech stocks, as represented by the S&P/ASX 300 Software and Services sector (the S&P/ASX All Tech had not been created) were trading at a forward P/E of 40.7 times earnings — which was 3.6 standard deviations above the market’s average forward P/E since 2001, of 19.3 times.

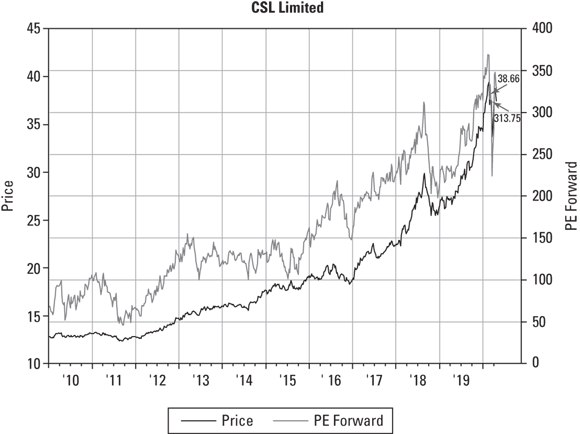

The market can get more comfortable paying a rising P/E: CSL is a great example of a growth stock where the rising P/E, and the expectations that implies, has been borne out by the earnings, and the share price has steadily trended higher (see Figure 5-1). But growth stocks live by the sword, and can die by it, too — when a much-fancied stock growth fails to deliver what the market expects, disappointment can be hefty.

Source: FactSet Prices

FIGURE 5-1: CSL share price and P/E, 2010–2020.

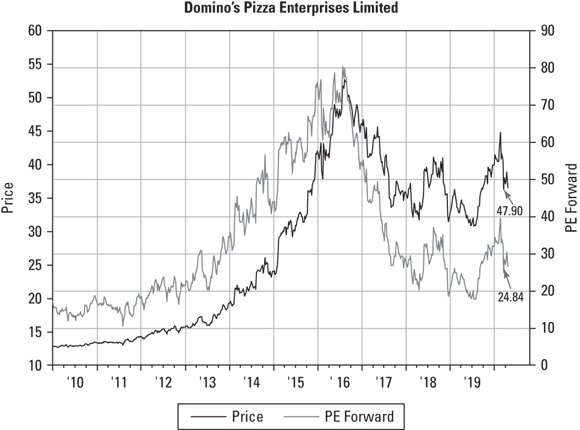

In the early part of the 2010s, investors pushed Domino’s Pizza to a forward P/E of 55 times earnings, as it rattled off several years of 40 per cent–plus profit growth. In the five years to August 2015, Domino’s delivered a total return of 732 per cent, compared to a 60 per cent gain in the major index. Even more impressively, any investor who snapped the share up in 2005 was sitting on a total return of 1,762 per cent, compared to a 97 per cent gain from the market. That’s what a growth stock can do.

At its core, Domino’s is a fast-food company; however, chief executive Don Meij continually told the market that Domino’s should be viewed as a technology company. With online ordering, mobile ordering, ‘four-click’ ordering, customers able to track the progress of their pizza via GPS, Domino’s walked the tech talk.

But, in doing so, Domino’s raised the bar on what growth investors expected. So, when, after several years of 40 per cent–plus growth, investors were given a forecast of only 20 per cent growth in 2015, they didn’t like it. Domino’s had been a standout performer, but at 55 times earnings, any bad news does not go down well. Two years later, even a record full-year profit could not save the stock, because it fell short of the company’s guidance. (An ugly scandal of Domino’s underpaying workers over a four-and-a-half-year period also didn’t help.) All of a sudden, Domino’s was trading at 30 times expected earnings — with the price following the ‘de-rated’ P/E lower. In 2020, it is trading at 25 times expected earnings (see Figure 5-2), and investors are yet to fully trust it again as a growth stock.

Source: FactSet Prices

FIGURE 5-2: Domino’s Pizza share price and P/E, 2010-2020.

Xero, which sells a cloud-based accounting software platform for small- and medium-sized businesses, is another example. The software giant broke through to profitability in the year to 30 March 2020, delivering on the promise of chief executive Steve Vamos to keep investing for growth but in a disciplined fashion. Xero added 467,000 new subscribers in that same period, had a total subscriber base of 2.29 million worldwide, with its biggest markets being Australia, the UK, New Zealand and the US. It increased revenue by 30 per cent to NZ$718.2 million (A$668.1 million) in FY20, while achieving a net profit of NZ$3.3 million (A$3.07 million). In earnings per share (EPS) terms, that came to 2 Kiwi cents (1.94 Aussie cents) a share.

That was good news for the P/E — because one could finally be calculated. As mentioned earlier in this section, on FY20 numbers, Xero was trading on 4,381 times earnings.

Clearly, that is ridiculous. Now that it is profitable, analysts’ consensus appears to be that Xero will earn 25.3 Australian cents a share in FY21, and 50.3 cents in FY22, which at $85.00, puts it on forward P/E multiples of 336 times FY21 earnings and 169 times FY22 earnings. Again, these are mortifying P/Es for a value-oriented investor, and they will not pay them.

Xero is obviously trading on huge expectations that its aggressive growth strategy will pay off in the long run, as tax and compliance for its SME (small- to medium-sized enterprises) market increasingly goes digital. The question will be whether these huge profits materialise to the extent that the market expects in 2021 and 2022. And the answer to this question will depend on the company’s ability to continue to innovate and provide a product to customers that they find superior, for their purposes, to the offerings from Xero’s competitors — of which there are plenty.

Growth investors buying Xero at these valuations simply believe that the market undervalues the leverage coming through the business, as it builds market share in what are large markets. Indeed, analysts estimate Xero’s total addressable market in Australia and New Zealand alone should reach NZ$1 billion (A$935 million a year), but its markets in the UK and the US are twice that size and ten times that size respectively.

It is a similar story with buy-now, pay-later (BNPL) fintech leader Afterpay. It is yet to make a profit, so traditional valuation measures like P/E aren’t valid. Afterpay doesn’t even have a forward P/E — analysts can’t see a profit until at least FY22. So why would anyone buy it?

Afterpay has grown from a $165 million micro-cap stock to a $12.3 billion member of the S&P/ASX 50 in just over four years. It has done this while becoming a verb to its customers, who love using it — more than 90 per cent of gross merchant volume (GMV) comes from repeat customers. Afterpay’s customer base and global underlying sales transactions have been growing hugely, and the shift to online purchases in the wake of COVID-19 has favoured it. Afterpay has shown that its payments business is scalable as it starts to grow in a big way in its new markets of the US and the UK. As this happens, the operating leverage — when most of a company’s costs are fixed, and increased sales volume starts to magnify the profits earned — is potentially massive, particularly in the US. That is what growth investors are buying in Afterpay.

Finding value stocks

Value investing is based on fundamental analysis. Value stocks are shares considered cheap because they’re out of favour with the market and are consequently priced low, relative to the company’s earnings or assets. The P/E and the dividend yield are important numbers for a value stock, but so is the ratio of price to net tangible asset (NTA) backing. The NTA backing represents the amount of tangible — that is, real — assets that stand behind each share. To work out NTA, subtract the value of any intangible assets, such as goodwill and brands, from shareholders’ equity, and divide by the number of shares on issue. (Under ASX reporting rules, companies must give their NTA in their interim [half-year] and full-year reports to shareholders, and show the equivalent figure for 12 months earlier.)

The long-term average P/E on the Australian market is about 14 times historical earnings; the average dividend yield is about 3.3 per cent (although full franking, at the large company tax rate of 30 per cent, turns that into a gross yield of 4.8 per cent).

Value investors usually look for stocks trading at P/Es well below the prevailing market P/E and well above the prevailing market dividend yield. But at all times they have to be aware of ‘value traps’, which are stocks that are trading where they are for very good reason. You can’t just pick out the ten lowest P/E ratios or the ten highest dividend yields. The highest dividend yield or the lowest P/E may be a result of a sharp fall in the share price. When aiming to buy stocks which trade at a discount to fair value, it is important to distinguish between those that are cheap, and those which represent good value.

Value investors like to buy good stocks at low P/Es — single-digit, if they can find them— that are not value traps, and ride these stocks as the market ‘re-rates’ them to a higher P/E. Value investors don’t chase high growth, high multiple stocks that are highly vulnerable to savage re-rates if earnings disappoint. But investors who lived by that rule would have missed out on stocks like Cochlear and CSL, which have continually traded on high multiples and delivered great returns.

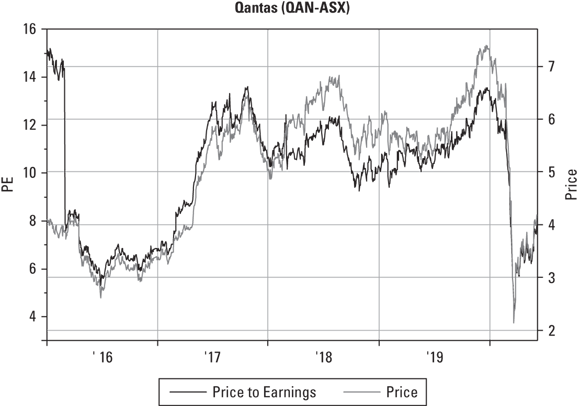

An example of a value stock was Qantas Airways, which in October 2017 was trading at a P/E (historical) of 14.5 times earnings. However, a general market slump in the latter half of 2018, weak consumer spending and intense domestic capacity battles saw the share price fall 18 per cent, and the P/E cut to 9 times. Value investors piled back into Qantas at levels around $5.50 to $5.60 a share. That buy was working a treat for them heading into 2020, with the share price above $7 and the P/E back to 13.7 times, but, unfortunately, the airline was pounded by the COVID-19 pandemic — which grounded aviation virtually completely. And like many companies in March 2020, Qantas was suddenly a value stock again — if you believed that travel patterns, both domestically and internationally, would eventually return to pre-COVID levels. Figure 5-3 shows the movement in the Qantas share price to March 2020.

Source: FactSet Prices

FIGURE 5-3: Qantas Airways share price and P/E, 2016–2020.

The rise of the technology stocks has put a lot of stress on 20th-century investment truisms — such as the Warren Buffett (see Chapter 11) Paradigm — which hold that a stock’s value is based on hard assets and reliable earnings. For many of the big tech growth stocks, value is based on the future revenue from the technology they’ve developed — and value investors struggle to reconcile this with their precepts.

For example, NTA — what in the US is called ‘book value’ — completely ignores assets such as brand name, patents and other intellectual property that’s been created by the company. Book value does not mean much to service-based firms with few tangible assets. For example, the bulk of Microsoft’s asset value is determined by its intellectual property, rather than physical assets. Microsoft’s share value (or Afterpay’s share value) bears little relation to its book value.

Knowing How Many Stocks to Buy

Many professional investors believe they can minimise their risk with about 40 stocks in their portfolios. They believe that this number adequately diversifies away the risk. Unfortunately, for most investors, owning 40 stocks isn’t an option. For an individual, no matter how much time you devote to monitoring your portfolio, you can’t keep track of 40 stocks — unless you’re very dedicated! As a single investor taking care of your own portfolio, you probably want no more than 15 shares, with a minimum of 10. Owning around 15 shares allows you to adequately monitor a portfolio and ensure that your investments are well-diversified.

Picking your sectors

The Australian sharemarket hosts companies involved in a huge variety of activities. In March 2002, the ASX adopted the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS), which was developed by Standard & Poor’s (S&P) and Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI), and established in 1999. The GICS structure initially consisted of ten sectors and 24 industry groups, into which investors can ‘drill down’ further to 67 industries and 147 sub-industries. A company is classified into the sector that most closely describes the business activities from which it generates most of its revenue.

In August 2016, a new sector, Real Estate, was created, elevated from its position as an industry group within the Financials Sector. That was the first time a new sector had been created within the GICS structure since its inception in 1999, and the update acknowledged the importance of real estate in the global economy.

When the ASX adopted the global standard, the new classification system had some drawbacks for Australian investors because the resources component of the market was split. The miners were placed in the materials index, which also contains stocks like James Hardie Industries (building materials) and Orica (chemicals and explosives), whereas the oil and gas companies were placed in the energy index. Investors couldn’t readily see how the entire resources sector was performing and what proportion of the index resources represented.

To redress this — and to support the metals and mining industry, which has been a major driver of economic growth in the 2000s — two new indices were launched in mid-2006 — the S&P/ASX 300 Metals and Mining index and the S&P/All Ordinaries Gold index — to provide benchmarks for these important segments of the Australian sharemarket. In addition, for each tier of the market, separate indices are now calculated for resources (stocks in the energy sector and the metals and mining industry sub-sector) and for industrials (all others in the materials sector). Table 5-2 gives you the details.

Selecting shares from these sectors can give you a diversified and protected portfolio. However, if you try to cover the entire list of industry groups, your portfolio may become cumbersome and difficult to follow. On the other hand, if you’re an income-oriented investor, and the search for a fully franked dividend yield leads you to end up owning shares in National Australia Bank, Commonwealth Bank and Westpac, you have a portfolio that’s too dependent on banks.

TABLE 5-2 GICS Economic Sectors and Industry Groups

GICS Economic Sectors |

GICS Industry Groups |

Energy |

Energy |

Materials |

Materials |

Industrials |

Capital goods; commercial services and supplies; transportation |

Consumer discretionary |

Automobiles and components; consumer durables and apparel; consumer services; retailing; media |

Consumer staples |

Food and staples retailing; food, beverage and tobacco; household and personal products |

Healthcare |

Healthcare equipment and services; pharmaceuticals, biotechnology and life sciences |

Financials |

Banks; diversified financial; insurance |

Information technology |

Software and services; technology, hardware and equipment; semiconductors and semiconductor equipment |

Real estate |

Real estate investment trusts (REITs); real estate development, management and services |

Telecommunications services |

Telecommunications services |

Utilities |

Utilities |

Source: Standard & Poor’s

Choosing core stocks

The Australian sharemarket is one of the most concentrated in the world. The S&P/ASX 50 index — the market’s largest 50 companies by value — accounts for about 61 per cent of the sharemarket’s total value.

That leaves roughly another 2,150 stocks making up the remaining 39 per cent. The 50 largest companies make up the core stocks to invest in, and are listed in Table 5-3.

TABLE 5-3 The Top 50 Companies on the ASX by Value as at May 2020

Stock |

Market Value ($billion) |

CSL |

136.75 |

Commonwealth Bank |

105.51 |

BHP |

92.50 |

Westpac Bank |

56.02 |

National Australia Bank |

51.39 |

ANZ Banking Group |

44.61 |

Woolworths |

43.83 |

Wesfarmers |

42.46 |

Macquarie Group |

37.28 |

Transurban |

37.20 |

Fortescue Metals Group |

37.07 |

Telstra |

36.04 |

Rio Tinto |

30.81 |

Goodman Group |

26.26 |

Newcrest Mining |

22.31 |

Woodside Petroleum |

20.89 |

Coles Group |

20.28 |

Fisher & Paykel Healthcare |

16.09 |

Brambles |

16.09 |

Aristocrat Leisure |

15.95 |

ASX |

15.93 |

Ramsay Health Care |

13.61 |

A2 Milk Company |

13.44 |

APA Group |

13.29 |

Amcor |

12.97 |

REA Group |

12.53 |

Sydney Airport |

12.32 |

Sonic Healthcare |

12.30 |

Insurance Australia Group |

12.20 |

Cochlear |

11.93 |

Xero |

11.68 |

Scentre Group |

11.42 |

Suncorp Group |

11.23 |

QBE Insurance |

11.01 |

Afterpay |

10.65 |

AGL Energy |

10.37 |

Santos |

10.10 |

Magellan Financial Group |

10.02 |

Origin Energy |

9.74 |

Dexus |

9.66 |

Northern Star |

9.64 |

James Hardie Industries |

9.59 |

Evolution Mining |

9.19 |

South32 |

8.97 |

ResMed |

8.97 |

Mirvac Group |

8.61 |

Aurizon |

8.60 |

Auckland International Airport |

7.88 |

Spark New Zealand |

7.84 |

GPT Group |

7.81 |

Source: Australian Securities Exchange Ltd

Since 2019, packaging giant Amcor’s parent entity, Amcor plc, has been incorporated in Jersey, with a tax domicile in the UK. Because it is no longer incorporated in Australia, franking is not applicable, and dividends are not franked. Both BHP and Rio Tinto, however, are dual-listed, and the London and Australian stock have equal rights over the company’s assets, with the only difference for investors being local tax laws — under this arrangement, holders of the Australian shares receive fully franked dividends.

Each sector has its top 50 representatives. The market has given these blue chip shares a capitalisation (value) that reflects their reliable nature. The S&P/ASX 50 contains the large-caps — the largest 50 companies by market capitalisation, or value. This cuts out at about $7.8 billion. (Market value is not the only criterion for inclusion in the S&P/ASX 50; liquidity, or turnover, is also required.) These are the elite group of stocks from which many of your core portfolio holdings come. Size, however, doesn’t necessarily equate to blue chip status.

Evaluating second-liners

Outside the top 50 come the mid-caps, usually considered to be the companies ranked 51 to 100 by value. This group is covered by the S&P/ASX Midcap 50, which starts at about $7.7 billion and ends at about $3.4 billion. Then come the small-caps, generally taken to mean those ranked between 100 and 300 by market capitalisation, as measured by the S&P/ASX Small Ordinaries index. This means that, roughly, any stock between $630 million and $3.4 billion in size is a small-cap.

Institutional investors usually consider only the stocks comprising the S&P/ASX 200 index — with a lower limit of about $1.2 billion — to be investment-grade (suitable for investment). Companies with stocks that lie within the 200 to 300 range may make the grade, but haven’t yet. But individual investors may have a different view than institutional funds of what constitutes investment grade.

The institutions typically concentrate their analysis and efforts on the top 100, although an increasing number of small ‘boutique’ managers look outside the top 300. Individual investors realise that they can use their research skills outside that range to find undervalued companies that the wider market has overlooked.

Potential leverage is even greater in the ‘micro-caps’, which are the stocks that lie outside the S&P/ASX All Ordinaries index (consisting of the 500 largest companies by market capitalisation). This cuts out at about $220 million. The companies below that level are even less researched than the small-caps, with many going about their business virtually unnoticed. Not many institutional fund managers go anywhere near the micro-caps because these stocks have low liquidity, meaning that if the manager gets it wrong, the fund may not be able to sell the shares, and may make a 100 per cent capital loss. On the other hand, the fund may be one of the only — if not the only — institutions on the share register, and may be invited on to the board for that reason.

But the attraction for the retail investor is that you can find value you simply can’t find in larger stocks. If you can get a micro-cap investment right, you’re looking at a star investment. A compound annual growth rate of 30 to 50 per cent over ten years is possible. As an example, 30 years ago, Fortescue Metals Group was a micro-cap; its market cap is now $37.1 billion. And 25 years ago, Sonic Healthcare was a micro-cap; its market cap is now $12.3 billion. Although the risk is far greater than investing in S&P/ASX 100 stocks, many investors like this sector of the market.

Outside the All Ordinaries index, after you cull resources explorers and research and development stocks, you have almost 500 profitable industrial companies. That’s a big universe in which to try to spot the next Fortescue Metals Group or Sonic Healthcare.

But at some point, when delving around the approximately 1,700 stocks that don’t make it into the S&P/ASX All Ordinaries Index (the top 500 by market value), you’ll find yourself dealing with the specialised world of the specs, or speculative stocks.

Gambling on specs

In Australia, a spec, or speculative stock, once meant a mineral or petroleum explorer. Nowadays, spec refers to any stock that does not have a positive financial track record, but may have prospects. Usually these prospects are called blue sky, meaning the possibility exists of very large gains in the future. Mineral- and oil-exploring companies are still specs, but a host of biotechnology and telecommunications hopefuls have also joined this category.

You can punt on a few speculative shares. If you set a limit on the amount you invest and you have a strategy for buying them, you can even come out ahead.

Diversifying through Managed Funds

When you analyse a diversified share portfolio, you have to keep in mind that it only contains shares. Full diversification requires another step. To protect your total investment, make sure your portfolio contains shares, property and interest-bearing investments, with a cash component kept in reserve. This kind of balanced portfolio is what a professionally managed diversified fund tries to put together.

Australian investors are big users of managed funds, with Australia having the fourth-largest managed funds market in the world. According to research firm Rainmaker, in 2019 Australians had $3 trillion invested through fund managers and super funds (including managed funds, wrap platforms — which allow an investor to hold shares, managed funds and a cash account, all under one umbrella — and all kinds of superannuation). This is up 135 per cent since 2010, and has increased by 9 per cent each year over the past decade. The nation’s growing superannuation kitty also accounts for $3 trillion (about one-third of super is directly invested by funds, while about one-third of money invested by fund managers comes from non-super).

Managed funds have opened up virtually all of the major asset classes to individual investors. Approximately 5,000 funds (excluding ETFs) are open for retail money. The $3 trillion managed funds pool is spread mostly across Australian shares ($595 billion), international shares ($600 billion), Australian bonds ($330 billion), real estate investment trusts ($110 billion), cash ($210 billion), direct property ($190 billion) and international fixed interest ($180 billion). Another $570 billion is invested in infrastructure, private equity, hedge funds and other ‘alternative’ assets.

Unlisted equity trusts are very popular. The largest of these are two index funds, the Vanguard International Shares Index Fund, with $14.8 billion of investors’ money, and its domestic stablemate, the Vanguard Australian Shares Index Fund, with $11.9 billion. Then comes the largest actively managed funds, both international equity funds — the Magellan Global Fund ($11.6 billion) and the MFS Global Equity Trust ($5.5 billion) The currency hedged version of the Vanguard International Shares Index Fund is next, with $5 billion, followed by the Fidelity Australian Equities Fund ($4.7 billion), the iShares Wholesale International Equity Index Fund ($4 billion), the CFS Colonial First State Wholesale Index Australia Share Fund ($3.7 billion) and two more international share funds, the Walter Scott Global Equity Fund ($3.7 billion) and the Antipodes Global Fund ($3.4 billion).

Real estate investment trusts (REITs) (see Chapter 8) are now a $110 billion component of the ASX, and property securities funds — these funds offer investors access to a portfolio of REITs, managed by professional fund managers — are also a $110 billion sector.

The other basic kinds of managed funds are

- Bond (or fixed-interest) funds, which own portfolios of government, semi-government and corporate bonds

- Cash management trusts (CMTs), which invest in term deposits, cash bank bills or short-term money market securities (instruments that can be quickly converted to actual cash)

- Mortgage funds, which hold a portfolio of mortgages over various kinds of property

In the past decade, the growing sophistication of the Australian investment marketplace has seen new kinds of managed funds emerge:

- ‘Absolute return’ funds, which invest for maximum return, without reference to any benchmark index (and carry higher risk as a result)

- Debt securities funds, which invest in sovereign (government) and corporate debt (or bonds)

- ‘Hedge’ funds, which claim the ability to make money regardless of what the share and bond markets are doing

- Income funds, designed to generate a reliable income for investors

The latest innovations are:

- Private equity funds: These funds invest in private companies, which are not listed on the stock market. In 1994, $71.1 million was invested in private equity; Australian investors now have $49 billion invested there.

- Global property securities and infrastructure securities funds: In the same way that global equity funds invest in overseas shares, global property securities and infrastructure securities funds invest in the much larger markets in those assets overseas. Global property securities is a $1.5 trillion market; global infrastructure securities is estimated to be even bigger, at $2.3 trillion.

- Socially responsible investing (SRI) funds: These funds’ investments are screened from an ethical or social perspective. They’re either directed away from unacceptable investments — for example, arms makers, gambling companies and alcohol/tobacco companies — or actively channelled to acceptable investments, such as companies showing good environmental or social behaviour, or with products that demonstrably serve a good purpose. SRI is a small but growing market in Australia. According to Rainmaker Information, dedicated ethical/SRI investment funds held $65 billion at March 2015, up from $6.2 billion at June 2010 — but if this is widened to include all of the superannuation funds now managed by fiduciaries that have signed up to environmental, social and governance (ESG) principles, the ESG investment sector in Australia is as large as $2 trillion.

Investing outside Australia

One strategy for managing your portfolio is to have some of your investments outside Australia. True diversification involves investment not only across a range of asset categories but also across local and foreign investments. The Australian sharemarket accounts for less than 2 per cent of the total capitalisation (or value) of the world’s sharemarkets. Your share portfolio (or asset portfolio in general) isn’t truly diversified unless it contains shares outside Australia.

Over the long term, international shares generate returns reasonably close to Australian shares. For example, according to research house Andex Charts, over the 30 years to December 2019, Australian shares (S&P/ASX All Ordinaries index) returned 9.2 per cent a year, compared to 7.7 per cent a year for international shares (MSCI World ex-Australia Gross Total Return Index). But the true value of having international shares in your portfolio is not just the return aspect. The true value is the added diversification these international shares give you, in the 98.2 per cent of the ‘investable’ stock market universe that is not in Australia.

That is more than one-quarter of your holding straight off. Financials and Materials (which holds the miners) make up almost 46 per cent of the S&P/ASX 200 index. That can be a big problem if an issue crops up in one of those industries — which has actually been the case at different times in the past decade, for both mining and banking. BHP, for example, did very little in share price growth terms between 2008 and 2016.

Of course, the Australian market is not as concentrated as it was — having biotech giant CSL as your biggest investment in an S&P/ASX 200 Index ETF (9.1 per cent of it) does help. In 2000, the Health Care sector accounted for just 1 per cent of the S&P/ASX 200, but it has grown to become the third-largest sector, at 13.4 per cent of the index, powered by CSL’s rise to the number-one spot by market capitalisation (CSL represents about 70 per cent of the S&P/ASX 200 Health Care sector by market capitalisation). The Health Care sector’s weighting has grown at a compound annual rate of about 18.5 per cent over 20 years. Since March 2011, the combined weight of Financials and Materials — Australia’s largest sectors—has decreased from 59.4 per cent to 45.3 per cent, while Health Care has more than quadrupled in weighting, from 3.2 per cent.

But the composition of the Australian market in recent years means that local investors don’t have access to some of the more advanced exposures. For example, the Australian exchange doesn’t have any major telecommunications suppliers or aerospace companies. Nor can Australians invest on a large scale in the technology industry — although it does have some emerging tech leaders, it has nothing of the scale of businesses such as Apple, Microsoft, Samsung, Amazon, Alphabet (Google’s parent company), Twitter, Facebook, Netflix, Tencent, Alibaba, Tesla and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing. We don’t have any large-cap drug companies such as Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, Roche, Novartis and Merck, or consumer champions of the likes of Nestlé, Unilever, AB InBev and Procter and Gamble. Investors who want to be well diversified have to look outside the Australian market more than ever before.

For the vast majority of Australian investors, international equities means shares from one of the major sharemarkets, most of which are in countries that are members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Table 5-4 charts Australia’s peer group of developed sharemarkets (these are the countries used in the MSCI World Index).

TABLE 5-4 Developed Sharemarkets

Australia |

Hong Kong |

Portugal |

Austria |

Ireland |

Singapore |

Belgium |

Israel |

Spain |

Canada |

Italy |

Sweden |

Denmark |

Japan |

Switzerland |

Finland |

Netherlands |

United Kingdom |

France |

New Zealand |

United States of America |

Germany |

Norway |

Source: MSCI

Standard & Poor’s adds South Korea, Luxembourg and Poland to the list shown in Table 5-4.

Outside the first tier are the emerging markets, as shown in Table 5-5. These are the countries from the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. Shares from the emerging markets are a separate and more risky asset class than the shares from the major world markets.

TABLE 5-5 Emerging Sharemarkets

Argentina |

India |

Russia |

Brazil |

Indonesia |

Saudi Arabia |

Chile |

Malaysia |

South Africa |

China |

Mexico |

South Korea |

Colombia |

Pakistan |

Taiwan |

Czech Republic |

Peru |

Thailand |

Egypt |

Philippines |

Turkey |

Greece |

Poland |

United Arab Emirates |

Hungary |

Qatar |

Source: MSCI

South Korea sits uncomfortably outside the ‘developed markets’, despite being the 11th largest economy and 13th largest individual sharemarket. MSCI classifies it as an emerging market because of problems with the convertibility of currency and restrictions on foreign stock transfers imposed by the government.

Trailing the emerging markets are the ‘frontier’ markets — the stock exchanges in places like Bahrain, Bangladesh, Croatia, Estonia, Jordan, Kenya, Lebanon, Lithuania, Nigeria, Tunisia and Vietnam.

Both portfolio theory and funds management practice accept that the addition of foreign shares to a domestic share portfolio lowers the portfolio’s level of risk without jeopardising the return; or, conversely, increases the return for the same level of risk. The addition of shares from emerging markets can also, surprisingly, lower overall risk. The key to success in diversification is having a wide enough range of investments to protect your overall portfolio.

However, because most Australian investors hold at least 70 per cent to 80 per cent of their assets in Australian dollars, many actually want exposure to currency fluctuation, seeing it as an extra layer of portfolio diversification. These investors want to include the relative performance of the foreign currency to the Australian currency as part of their investment strategy.

Investing overseas requires some expert knowledge and constant monitoring, but it can be done quite easily. Knowing your way around the Australian sharemarket’s 2,200 stocks and making decisions about which stocks you want to buy isn’t easy — and if you decide that you want to invest in US shares, your decision-making process can become even more complicated. That’s why many people — even those who are self-reliant investors in the Australian marketplace — look to ETFs or managed funds for their international exposure. These people prefer to buy the simple international exposure and diversification of an ETF, or the strategy and investment expertise offered by an active managed fund.

But if you want to choose and manage your overseas investments personally, this can be done. Most of the large online brokers offer international stock trading, for as cheap as US$9.90 or £8.00 a trade. Interactive Brokers Australia P/L even goes as low as US$1.00 or £6.00 a trade but will charge a monthly fee of A$10.00 if monthly commissions are less than $US10.00.

In this way, nothing is stopping an Australian investor buying (and trading) major high-growth global stocks, either through the shares or American Depositary Receipts (ADRs), by which many top global companies trade on the US sharemarket.

The large number of investment opportunities available means you can readily assemble a well-diversified portfolio with some of your assets working for you outside the Australian economy. The downside to this increased sophistication is that intelligent investment is more complicated than ever before. However, by practising some basic diversification strategies, you can increase both your opportunities and your successes.

At the time of writing, Chi-X traded TraCRs of the following US shares: AT&T, Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Bank of America, Berkshire Hathaway, Boeing, Caterpillar, Costco, Disney, ExxonMobil, Facebook, General Electric, IBM, Intel, JP Morgan Chase, Johnson & Johnson, Lockheed Martin, McDonalds, Merck, Microsoft, NVIDIA, Netflix, Nike, Oracle, PepsiCo, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, Starbucks and Visa.

Another product that gives access to global shares is fund manager AtlasTrend’s diversified portfolios, of ten to 15 major international shares each, with capitalisations of US$1 billion or more, built around three major ‘trends’, which are long-term structural investment themes that the manager believes have global impact and strong growth characteristics. At the time of writing, Atlas Trend offered

- Big Data Big: This portfolio invests in areas such as technology, software, cloud computing, data centres, cyber-security and networking. Examples of stocks held in this trend were Alphabet and Apple.

- Clean Disruption: This invests in areas such as renewable energy, battery technology, electric vehicles, recycling and efficient materials. Examples of stocks held in this trend were BYD Company and Vestas Wind Systems.

- Online Shopping Spree: This invests in areas such as e-commerce retailers, logistics and online marketplaces. Examples of stocks held in this trend were Amazon and FedEx.

AtlasTrend makes global investment very easy, with minimum investment amounts of $1,000 (in one dollop) or $100 a month. Investment costs are 0.99 per cent a year, plus a 15 per cent performance fee if the investment makes a return above the MSCI World Net Total Return ex-Australia Index, in Australian dollars.

Considering Alternative Investments

Increasingly, savvy investors are considering allocating fairly large (10 per cent to 20 per cent) chunks of their portfolio to ‘alternative’ investments — that is, those that are not the traditional building blocks of a portfolio, being shares, cash, bonds and property. Alternative assets have different returns streams from mainstream investments, such as bonds and equities, where payments in the form of coupons or dividends can generally be expected every six months. This means alternative assets can help to diversify an investment portfolio.

The term alternative investments is usually taken to include:

- Hedge funds, which are managed funds that can invest across many different markets and strategies, with maximum flexibility, so they can make money regardless of what the share and bond markets are doing. They can lose money, too.

- Managed futures/commodity trading adviser (CTAs) strategies.

- Absolute-return equity-based funds, such as long–short funds, which will simultaneously go long (buy) under-valued stocks and short (sell) over-valued securities, and ‘market-neutral’ funds, which try to deliver above-market returns with lower risk by hedging out market risk. These look to negate the impact and risk of general market movements, and isolate the pure returns of individual stocks.

- Private equity — that is, capital invested in a private company not yet listed on the sharemarket. (A private equity investment made at a very early stage — for example, before the company has earned any revenue — is known as ‘venture capital’, and is sometimes considered a discrete investment class.)

- Infrastructure assets, where income streams can be generous but not without risk.

- High-yield assets — for example, funds that invest in distressed debt, junk bonds and mezzanine debt.

- Commodities, such as precious and base metals, oil and energy, and soft (agricultural) commodities.

- Agribusiness, such as investment in forestry, farming or horticultural businesses.

- Art and other collectible items, such as coins and wine.

More recently, the range of alternative assets available has been widened to include investment in insurance-linked securities (the value of which is driven by insurance events); water entitlements (traded in the Australian water market); ‘social impact’ investments, where the investment both earns a financial return and generates a targeted positive social outcome; shipping funds; aircraft and other equipment leasing; weather-related derivatives; volatility derivatives; carbon-dioxide emissions trading; and cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin. Like gold, Bitcoin is increasingly being seen as a genuine member of the liquid (easily sellable) part of the alternatives asset class.

Over the past four decades, the need for diversification has been clearly demonstrated as, repeatedly, all the asset classes took their turn suffering big slumps. The sharemarket crashed in October 1987, and fell badly again in 1990, 2000, 2001, the GFC crash of 2007–2009, 2018 and 2020. The bond market had its version of a crash in 1994. (US 30-year Treasury bond yields spiked from below 6 per cent to above 8 per cent, a massive move for that market. Remember: Bond prices fall as yields rise.) Australian cash rates fell by two-thirds from 1989 to 1994, and later traced an even deeper decline — from 7.25 per cent in August 2008, the cash rate fell to 3 per cent in just nine months, and has since been in a slow slide to its 2020 record low of 0.25 per cent. That slide caused the average three-year term deposit rate in Australia to plunge from 7 per cent to 1.25 per cent.

Over the past four decades, the need for diversification has been clearly demonstrated as, repeatedly, all the asset classes took their turn suffering big slumps. The sharemarket crashed in October 1987, and fell badly again in 1990, 2000, 2001, the GFC crash of 2007–2009, 2018 and 2020. The bond market had its version of a crash in 1994. (US 30-year Treasury bond yields spiked from below 6 per cent to above 8 per cent, a massive move for that market. Remember: Bond prices fall as yields rise.) Australian cash rates fell by two-thirds from 1989 to 1994, and later traced an even deeper decline — from 7.25 per cent in August 2008, the cash rate fell to 3 per cent in just nine months, and has since been in a slow slide to its 2020 record low of 0.25 per cent. That slide caused the average three-year term deposit rate in Australia to plunge from 7 per cent to 1.25 per cent. Growth outperformed value in the second half of the 2010s — and then another crash in 2020 brought great pickings for the value investors. As a non-professional investor, if you can identify an undervalued bargain, by all means buy it, and if you’re satisfied that you’ve identified a standout growth candidate, buy it too. Your portfolio can benefit from both approaches.

Growth outperformed value in the second half of the 2010s — and then another crash in 2020 brought great pickings for the value investors. As a non-professional investor, if you can identify an undervalued bargain, by all means buy it, and if you’re satisfied that you’ve identified a standout growth candidate, buy it too. Your portfolio can benefit from both approaches. Growth investors are looking at other measurements than P/E. For example, they are looking at Xero’s annualised monthly recurring revenue (AMRR), average revenue per user (ARPU) and its total subscriber lifetime value (LTV). The latter measures the revenue that an average subscriber represents to a software-as-a-service (SaaS) company over the subscriber’s lifetime.

Growth investors are looking at other measurements than P/E. For example, they are looking at Xero’s annualised monthly recurring revenue (AMRR), average revenue per user (ARPU) and its total subscriber lifetime value (LTV). The latter measures the revenue that an average subscriber represents to a software-as-a-service (SaaS) company over the subscriber’s lifetime. As the world emerges from the pandemic, there will likely be fewer people travelling for some time, and the international travel business in particular faces a protracted slowdown. But Qantas will emerge from the pandemic a more streamlined company, cashed-up, and with huge untapped value in its Frequent Flyer business. It is a high-quality, very well-run company, that will survive and prosper.

As the world emerges from the pandemic, there will likely be fewer people travelling for some time, and the international travel business in particular faces a protracted slowdown. But Qantas will emerge from the pandemic a more streamlined company, cashed-up, and with huge untapped value in its Frequent Flyer business. It is a high-quality, very well-run company, that will survive and prosper.