Chapter 4

Assessing Your Risk

IN THIS CHAPTER

Being honest with yourself

Being honest with yourself

Exposing your investments to risk

Exposing your investments to risk

Picking the danger signals

Picking the danger signals

I once studied English literature and language and thought myself a traditionalist, particularly when watching Shakespeare’s plays. That perception changed when I saw the Bell Shakespeare Company’s version of The Merchant of Venice, with the characters dressed in snappy suits and sunglasses with mobile telephones glued to their ears. Antonio and his friends looked like stockbrokers — the Venetian equivalent. I was hooked on this modern interpretation. I found out that Antonio, like any finance professional, understood that diversification helps to spread the risk.

My ventures are not in one bottom trusted

Nor to one place; nor is my whole estate

Upon the fortune of this present year:

Therefore my merchandise makes me not sad.

Well, he thought he was protected by diversification, until all his ships hit bad weather and were wrecked. The problem for Antonio was that, although his ventures were all seemingly well diversified, and his ships sailed from different places, his investments were all the same asset class — trading ships. In this chapter, I discuss how many investors think they’ve covered their risk through diversification or hedging until some unforeseen event changes everything.

Gambling or Investing?

Risk is the chance of an unexpected event happening or a particular objective or outcome not being attained; its basis is the unpredictability of the future. Risk is a relative concept that alters with circumstances and personalities. In the context of finance, risk means the possibility of losing invested capital. However, an investment doesn’t have to be unprofitable to be an unacceptable risk; the major aim of investing is to generate a financial return above inflation.

Like successful roulette players — if such people exist — successful investors understand that risk is merely the other side of gain, and you can’t have gain without risk. An experienced investor knows that the promise of high percentage returns usually means increased risk. Sometimes, people new to investing don’t make the proper connection between risk and return.

Measuring risk mathematically is possible. The statistical terms of variance and standard deviation measure the volatility of a security’s actual return from its expected return, but that’s a discussion that belongs in another book. However, in discussing the risk of a particular stock, standard deviation of return is a useful concept. The standard deviation measures the spread of a sample of numbers and the extent to which each of the numbers in the sample varies from the average. A low standard deviation of return in a stock means that it’s a relatively less risky investment.

Another way of measuring risk uses the beta factor, a statistical measure of a share’s volatility (see the sidebar ‘Measuring volatility’) compared with the overall market. The beta factor measures a share price’s movement against that of the market as a whole (for example, the S&P/All Ordinaries index). The index has a beta factor of 1.0. If the share has a beta factor of less than 1.0, you can expect its price to move proportionately less than the index. If the share has a beta factor greater than 1.0, you can expect the share price to rise or fall to a greater extent than the index. The higher the beta factor, the more volatile is a share’s price.

The bad news: Risk is inescapable

All investors store money for future use. What most concerns you is the possibility of losing the money you’re saving. Now you’re talking risk! However, some professional investors set even higher risk levels than the average individual investor. For example, a fund manager may decide that her fund will outperform the S&P/ASX 200 index. The manager’s main risk is not achieving this goal. Even if the fund’s investments make money, if they don’t exceed the return of the index, the portfolio has had a bad year. Investors know the fund failed to reach its benchmark, which can cause some fund investors to take their money elsewhere.

Wary investors associate risk with cataclysmic events, such as the great sharemarket crashes of 1929, 1987, 2007–09 and 2020, the bond market downturn in 1994 and the tech wreck of 2000. These events spark memories of collapsing companies, bankruptcies and share certificates made worthless overnight.

All assets offer a different reward and a different level of risk. They range from government bonds, which are considered a risk-free asset because they’re guaranteed by the government, to futures contracts and options, where you can easily lose all of your money. With futures assets, you’re taking on higher risk than if you buy an Australian government ten-year Treasury bond, but you’re entitled to expect a far greater return. Successful investing means balancing the return against the risk.

The good news: Risk is manageable

You can offset risk either by hedging or diversification. Hedging is investing in one asset to offset the risk to another. Diversification is the spreading of funds across a variety of investments to soften the impact on your portfolio return if one investment performs badly. You can also include a few individual risk shares in a portfolio that’s otherwise well balanced.

Hedging is a form of insurance in which you try to make two opposite investments, so that if one goes wrong, the other can nullify or lessen the blow. When buying or selling shares, you can use the derivatives markets (exchange-traded options or warrants) to take the opposite position to an investment in the sharemarket. You may own shares in National Australia Bank (NAB), but also own a put option (the right to sell the shares at a predetermined price) in NAB that will increase in value if the share price falls.

Spreading the news: Risk increases your return

The mathematics involved in risk-and-return theory are mind-boggling. In taking your first steps into share investing, you may come across terms such as ‘modern portfolio theory’ and the ‘capital-asset pricing model’. These are complicated theories for money nerds to play around with and are far beyond the scope of this book — and far beyond your humble author, too! Simpler ways exist to understand how risk increases your return. For example, when you have an asset that earns a rate of return every year, you end up with a sample of yearly returns. When you’ve owned the asset for two years, you can calculate the average return that the asset has earned. However, the share return at any given time may fluctuate a good deal more than your calculated average. The wider the variance of the extremes, the more volatile the asset and the higher its standard deviation.

Assessing Your Risk

As an investor, you have to deal with different kinds of risk. In some instances, you may be able to lessen the risk, but in other situations, the degree of risk may be unchangeable. Some investments are like a cocktail of several kinds of risk. Understanding how each type operates helps you put together a balanced portfolio.

Market risk

Market risk is the risk you take by being in the sharemarket, trying to capture the higher return generated by shares (which, with dividends included, has run at 11.8 per cent a year since 1950). As the market fluctuates, the price of a company’s shares varies too, independent of factors specific to the company. The higher prices rise and the more the market moves away from its long-term trendline, the more likely a correction will take place (when a share price or market index falls by 10 per cent or more).

The crash of 1987 stripped 25 per cent from the value of the All Ordinaries Index in one day. The slump knocked the very best stocks off their perch for a year to 18 months. Many others in the top 100 took three years to get above their pre-crash highs and some stocks never recovered. The massive bear market of November 2007 to February 2009 stripped 54 per cent from the value of the Australian sharemarket — once again, setting many companies a long and difficult task to regain and surpass their previous share-price high-points.

In February–March 2020, the damage to the index was 38 per cent, and considerably more than that to the share prices and market valuations of many individual stocks (refer to Chapter 3 for some examples).

CSL, for example, was trading at $34.50 before the market slump started in November 2007 — fast-forward to February 2020, just before another big slump, and it was trading almost ten times higher, at $341.00. But it must be said, not every stock has done that well.

Every sharemarket company incurs a cocktail of risks, daily, in going about its business. That’s part and parcel of business — running risk to generate return.

Financial risk

Every company has financial risk, that is, the possibility of the company getting into financial difficulties. Managing the finances of a publicly listed company isn’t an easy task. The company may have borrowed too heavily and exposed itself to danger from rising interest rates, a recession or, worst of all, a credit crunch — when banks stop lending. That’s what happened in the GFC, particularly after Lehman Brothers collapsed and the global banking system temporarily froze. Suddenly, after years of cheap credit, debt was a dirty word. Over-borrowed companies’ share prices simply sank like stones on the sharemarket, when they couldn’t roll over their debt.

Structured finance specialist Allco Finance Group, which was valued at $5 billion at its peak in February 2007 — shortly before it was the key player in a consortium that tried to take over Qantas — fell 98.9 per cent on the way to administration in November 2008, owing more than $1 billion. Investment bank Babcock & Brown, which floated at $5 in 2004 and reached a peak of $33.90 in mid-2007 (when it was valued at $10 billion on the ASX), fell 99.6 per cent — 45 per cent of that in two days in June 2008 — before it limped into administration in March 2009.

In January 2008, financial services and property group MFS lost almost 70 per cent of its value during a phone call — a conference call with analysts in which chief executive Michael King revealed a shock $550 million capital raising, almost three times larger than the analysts were expecting. MFS changed its name to Octaviar, but went into liquidation in July 2009.

Shopping centre owner Centro Properties lost 99.4 per cent between February 2007 and April 2009; 84.5 per cent of that value was lost in two trading days, in December 2007, after it revealed that it couldn’t roll over $4 billion in short-term debt. (Centro did not go into administration; in fact, it never missed an interest payment. Its banks sold the debt to the bondholders, who ultimately swapped the debt for equity in a new company, Federation Centres, which in 2015 merged with Novion Property Group to form Vicinity Centres.)

Childcare centre operator ABC Learning plunged 92 per cent on its way into receivership, and infrastructure operator Asciano fell 96.5 per cent, from $11.64 in June 2007 to 40.8 cents in February 2009. (Asciano was taken over at $9.13 a share in mid-2016 by logistics group Qube, Canada’s Brookfield Infrastructure and a group of international pension funds.) The end of the road in share price terms for Allco Finance Group, Babcock & Brown, MFS/Octaviar, Centro Properties and ABC Learning is shown in Figure 4-1.

Data source: © IRESS Market Technology

FIGURE 4-1: Allco Finance Group, Babcock & Brown, MFS, Centro Properties and ABC Learning share prices, 2005–09.

Real estate investment trusts (REITs) with high debt levels were hammered just as badly. FKP Property, Goodman Group and ING Industrial Fund all fell more than 95 per cent; GPT lost just less than that. Abacus Property and Australand both lost 91 per cent. Anywhere the market saw short-term refinancing risk, or simply too much debt, it was much the same. (Although well short of their pre-GFC unit-price highs, Goodman Group and GPT remain pillars of the A-REIT sector.)

The worst slump of all was toll road company BrisConnections, which was floated by Macquarie Group and Deutsche Bank with awful timing — in August 2008, when over-geared infrastructure stocks were badly on the nose. BrisConnections’ $1 partly paid units fell 59 per cent on their first day of trading, and by May 2009 they were trading at 0.1 cent (the lowest tradeable price on the ASX), for a fall of 99.9 per cent.

At the time, holders of the units were still obliged to pay the second and third instalments of the purchase price, of $1 each; naturally, they didn’t want to do so. Many decided not to, amid threats of legal action. Eventually Macquarie Group and Deutsche Bank took up the unwanted units, leaving them owning 79 per cent of the company. The fully paid (to $3) units returned to trading in January 2010, at $1.30; the company’s toll road in Brisbane, the Airport Link, opened in July 2012 but failed to meet its traffic targets, and the units were suspended for good in November 2012, at 40 cents.

Another example of financial risk involved the mining group Sons of Gwalia, which collapsed in 2004. Better known as a gold miner, Sons of Gwalia was also the world’s largest producer of tantalum, a metal widely used in the electronics industry, and lithium, a metal used in aerospace and healthcare. In 2001, Sons of Gwalia was valued at more than $1 billion. Three years later it collapsed, taking about $250 million of shareholders’ funds with it. Sons of Gwalia got its gold hedging wrong. It had forward sales agreements that committed it to deliver gold, but the reserves that it had to mine were insufficient to meet those commitments. A $500 million liability on its gold and foreign exchange hedging ‘book’ brought it down.

Data source: © IRESS Market Technology

FIGURE 4-2: Sons of Gwalia share price, 2001–04.

Another kind of financial risk is when the price of a company’s product drops for reasons beyond its control. Agrichemical company Nufarm encountered this problem between 2008 and 2010 when prices for its main weedkiller product, glyphosate, slumped as cheaper Chinese products and weak demand hit the market. Nufarm’s margins more than halved over the period, forcing the company into a loss in the 2009–10 financial year, its first loss in more than a decade. Nufarm was forced to slash its earnings forecasts in half in July 2010, triggering breaches of debt covenants (agreements between a company and its bankers that the company should operate within certain limits) that left it at the mercy of its banks. Nufarm shares slumped by 70 per cent in 2010, and by early 2020, the share price had not yet fully recovered.

Commodity risk

A commodity is a tradeable good; the word is generally used in the context of physical commodities — basic resources and agricultural products — that are bought and sold all over the world, and have actively traded markets. ‘Hard’ commodities are those extracted by mining, while ‘soft’ commodities are agricultural goods that are grown. You also get ‘energy’ commodities, such as oil and gas. Companies that produce commodities are exposed to commodity risk, which refers to the uncertainty caused by the fluctuation of the price of commodities in the market, and thus the income derived from producing them.

The surge in Chinese economic growth through the 2000s — peaking at an exhilarating 14 per cent in 2007 — sent the price of iron ore rocketing, from US$12.45 a tonne in June 2000 to US$187.18 in February 2011. This was fabulous news for Australian iron ore miners, who dug up as much ore as they could and shipped it to China. Moreover, any mining company that could do so committed to huge volume expansions to take advantage of the higher prices. BHP, Rio Tinto and Fortescue Metals all forged ahead with big expansion plans, as did the other major iron ore player, Valé of Brazil. New players also entered the market. But as is typical with supply responses to high prices, the extra tonnes began to arrive just as the demand from China began to slow on the back of a weakening economic growth rate. (This was to be expected, because China had moved slowly towards a more consumer-spending and services-oriented economy, and relied less on massive infrastructure projects to boost its growth.)

By 2015, China’s GDP growth rate had fallen to 7 per cent a year, and although this is still massive growth, given the sheer size of the Chinese economy, it meant that iron ore was less in demand. Sure enough, by December 2015, the iron ore price was under US$50 a tonne.

This was bad enough for the major producers, BHP and Rio Tinto, but at least they were diversified commodity producers. For the miners that only produced iron ore, however, it was a disaster, as the sagging iron ore price threatened to fall below their cost of production.

The largest of the single-focus iron ore miners, Fortescue Metals, dropped 71 per cent on the ASX. The smaller iron ore ‘juniors’ fared even worse: Gindalbie Metals slumped 98.5 per cent, Atlas Iron lost 99 per cent, BC Iron plunged 94.5 per cent, and Mount Gibson Iron fell 91 per cent. Gindalbie and Atlas Iron bit the bullet, and stopped mining temporarily. Gindalbie was eventually taken over by a Chinese company in 2019, Atlas Iron was taken over by Gina Rinehart’s Hancock Prospecting in 2018, and BC Iron got out of the iron ore business and changed its name to BCI Minerals. Only Mount Gibson Iron is still producing (after an unfortunate hiatus — see the section ‘Engineering risk’, later in this chapter, for further details).

However, from the low point mid-decade, iron ore kicked off again, helped by a catastrophic tailings dam failure in Brazil, to reach US$120 by July 2019. The tragedy in Brazil cut the production of the dam’s owner, Vale, by one-fifth in 2019, to 302 million tonnes (allowing Rio Tinto to topple Vale as the world’s largest producer), and continued production difficulties at Vale have kept iron ore prices above US$90 a tonne — helped by China’s determination to re-stimulate its economy after the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. And as Fortescue continues to drive its cost of production ever-lower, the dark days of $1.50 in January 2016 seem a long way away for Fortescue, at $13.84.

Liquidity risk

Liquidity risk is the possibility that you’ll be unable to get out of an investment because no-one will buy your shares. Holders of internet stocks after the April 2000 tech wreck know all about liquidity risk, as do owners of small company stocks during the GFC. You can’t sell shares if no-one wants to buy them. If liquidity risk bothers you, don’t stray out of the top 100 stocks.

Business risk

Each share carries business risk — that is, the possibility that the company will make a mistake in its business. Business risk is part and parcel of the capitalist system. But business risk can very soon become financial risk — a very good reason to have a well-diversified share portfolio.

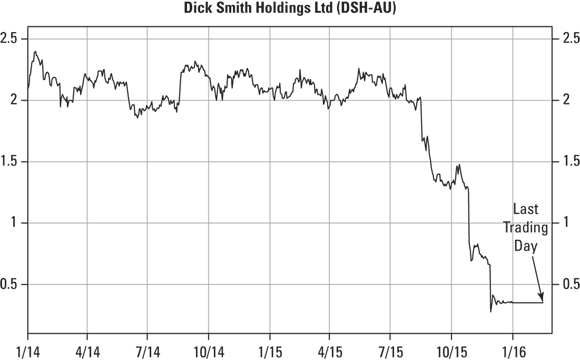

In the IPO, 66.2 per cent of Dick Smith was sold, with Anchorage holding on to 47.3 million shares or 20 per cent. However, Anchorage had fully sold out by September 2014.

By January 2016, Dick Smith Holdings was in receivership, with 393 stores and 3,300 employees. The appointment of administrators and receivers came after two painful earnings downgrades in its last six months and a $60 million inventory write-off that sent shares plunging by as much as 70 per cent, hitting 20 cents at one point. By the time Dick Smith shares went under, the shares had slumped by 84 per cent.

What blew the company up were inventory problems — it bought too much inventory in anticipation of certain sales levels, and then didn’t achieve those levels. Court hearings into the collapse heard that Dick Smith’s management chose its products to maximise rebates (the money that retailers get from suppliers to stock and promote their goods), rather than on what its customers actually wanted to buy. Worse, the receivers alleged that the company breached accounting standards by booking those rebates as profit before it actually sold the products and was paid. As rebate-carrying inventory built up, the company had difficulties securing finance to purchase new stock.

This became a vicious circle — the reliance on rebates ultimately led to slowing of inventory turnover rates, because the products were generally less popular with customers. Eventually, reported the company’s administrator, ‘heavy discounts were needed to sell the rebated stock, destroying the margin uplift that the rebate sought to achieve and, in some cases, the stock could not be sold at all and became obsolete.’

The company committed some of the cardinal sins — it grew too fast, used short-term working capital to fund long-term assets and (after stock write downs) wasn’t profitable. The bottom line is that there was insufficient profitability or insufficient access to funding for growth, and its executive remuneration appeared to be too focused on the short term. In November 2015, the company revealed it would write-down the value of its inventories by 20 per cent, or $60 million. Dick Smith became insolvent because it was unable to make scheduled payments to its financiers, and breached its banking facility agreements in December 2015. The company tried a last-ditch ‘70 per cent off everything’ sale just before Christmas 2015, but it didn’t work.

In the end, Dick Smith had $1.3 billion in sales but collapsed owing its creditors $260 million. The retailer’s staff received their full entitlements, but shareholders did their dough.

Figure 4-3 shows Dick Smith Holdings’ share price over its life as a listed company.

Source: FactSet Prices

FIGURE 4-3: Dick Smith Holdings share price, 2013–16.

Product risk

Similar to business risk, some companies carry product risk — that is, the possibility that their products may fail. This is a particular concern for biotech shareholders, because a failed clinical trial can make a major dent in their investment.

Just ask the shareholders of Factor Therapeutics, which in November 2018 was testing its wound-dressing drug VF001 to treat venous leg ulcers. But the trial failed — or, in the precise language of biotech, ‘analysis demonstrated no clinically meaningful or statistically significant difference in measures of wound healing compared to placebo’ — and the shares were virtually wiped out, closing the fateful day down 97 per cent at 0.2 cents. Ongoing development of VF001 for all indications was halted.

‘We started with hope and belief based on the evidence we had that it would be effective and we could take it to market,’ Factor Therapeutics chair Dr Cherrell Hirst told a conference call with investors on the day it reported the trial result. ‘But the results were strongly negative and there was no ambiguity.’

The company is still looking for a new business opportunity that involves clinical-stage (or near to clinical-stage) assets with sufficient data to support a high likelihood of successful commercialisation.

It was an even worse story for shareholders of Innate Immunotherapeutics in June 2017. Innate was developing a drug called MIS416 for the treatment of multiple sclerosis, specifically the secondary progressive stage of the disease. MIS416 looked to stimulate the body’s immune system to reduce inflammation, and protect — and even repair some of the damage the disease causes to — the central nervous system. No approved drugs for the effective treatment of secondary progressive MS were yet available, so the drug had blockbuster ($1 billion-plus) sales potential.

Innate shareholders would have gained confidence from the data from an earlier clinical trial, as well as the fact that the drug had ‘investigational new drug’ (IND) status from the US Food & Drug Administration (FDA). Anecdotal evidence was also coming from New Zealand, where it was being used under a ‘compassionate’ patient program, because patients had no other effective treatment options. This indicated the drug actually reversed some of the disabilities that came with MS, and looked to be particularly effective at improving physical strength, energy levels and lessening pain.

That’s what makes it even worse for Innate shareholders — the drug looked good. But again came the dread words — ‘no clinically meaningful or statistically significant difference in measures of neuro-muscular function or patient-reported outcomes.’ The shares fell 90 per cent in a matter of minutes. (Incidentally, the slump in Innate Immunotherapeutics shares claimed the job of a US congressman, who was a director of the company and its largest shareholder: Chris Collins resigned from Congress after being charged with insider trading in Innate shares, of which he was found guilty. He was jailed in 2020.)

Innate Immunotherapeutics is now known as Amplia Therapeutics (see Chapter 8), which has a drug candidate that has received two ‘orphan drug’ designations from the FDA. This status is given to drugs intended to treat, prevent or diagnose a rare disease.

Not even Australia’s world-leading medical device makers — hearing aid maker Cochlear and sleep-breathing product developer ResMed — have been immune from this kind of issue. In September 2011, Cochlear issued a global recall of its best-selling product line after noticing a mysterious rise in the number of its hearing implants that had suddenly stopped working. The share price fell 25 per cent in a morning. And in May 2015, ResMed shocked the market with the results of a clinical trial that they’d hoped would show that its sleep therapy products protected heart attack victims; instead, the trial result showed that a group of patients were put at increased risk of dying. The sharemarket reacted by cutting 27 per cent from ResMed’s share price.

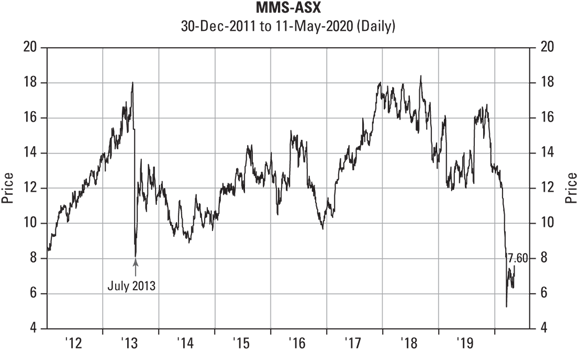

Legislative risk

Another form of specific risk is legislative risk, which is the possibility that a change in legislation may adversely affect a company in which you own shares. (This is also known as regulatory risk.) No better example of this exists than the experience of salary packaging and fleet management services company McMillan Shakespeare in July 2013. McMillan Shakespeare was blindsided by the then Labor Government’s proposed changes to fringe benefits tax (FBT) laws in relation to car use for business. As a major player in the car-leasing market, McMillan Shakespeare immediately stood to lose up to 40 per cent of its earnings. The shares promptly fell 55 per cent.

Until then, McMillan Shakespeare had been a market darling, rising from a post-GFC low of $2 to $18. What most angered McMillan Shakespeare and its fellow car-leasing companies was the lack of consultation — the change was sprung on the industry by the government, out of the blue. Hence the dramatic share price fall. Even though the incoming Coalition government overturned Labor’s changes later that year, the shares took five years to recover the lost ground. Complicating matters were also involved — competition intensified in MMS’s business areas in Australia, New Zealand and the UK; the company’s efforts to diversify resulted in a class action over its extended car warranty business NWC; and a planned merger with fellow auto leasing company Eclipx fell through. The bottom line, however, is that McMillan Shakespeare was badly bruised by a government decision that it didn’t see coming — see Figure 4-4. (The COVID-19 crash took 58 per cent off the MMS share price, but that’s a different kind of risk.)

Source: FactSet Prices

FIGURE 4-4: McMillan Shakespeare share price, 2011–20.

As mentioned, a close relative of legislative risk is regulatory risk. In September 2018, life-insurance distributor Freedom Insurance experienced a gruelling appearance at the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry, in which its business model of directly selling insurance through cold-calling (unsolicited phone calls) was exposed as having involved high-pressure sales tactics, and high commission payments. As a result of the Royal Commission hearings, in December 2018, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) banned insurers from cold-calling customers to sell life and consumer credit products. At a stroke, that ban took away Freedom Insurance’s business model. Between them, the Royal Commission hearings and the ASIC ban stripped 95 per cent from Freedom Insurance’s market value — and left the company no option but to voluntarily put itself into receivership.

Technical risk

Occasionally companies developing ambitious new projects using new technology can come unstuck on technical risk, when the technology proves difficult to bed down or simply doesn’t work.

Anaconda Nickel was a Western Australian nickel company that in the mid-1990s, saw the potential of large, already-discovered laterite deposits in the northern goldfields of WA. These deposits were discovered in the nickel boom of the early 1970s but were left untouched because they were considered to be uneconomic. But with the development of a new process called pressure-acid-leach, suddenly these deposits became viable.

Anaconda embarked on an ambitious $1 billion world-scale 45,000 tonnes-a-year nickel plant at Murrin Murrin, near Leonora in Western Australia. Anaconda had no difficulty raising the money, with mining giant Anglo American and Swiss metal trader Glencore among the project backers. The plan was to expand production at Murrin Murrin to 100,000 tonnes of nickel and become one of the world’s biggest producers. In 1999, Anaconda was a top 100 company, valued at $1.5 billion. However, the cracks in the plan were emerging.

Anaconda was in a hurry to get into production, so it skipped the demonstration plant stage and went straight from the laboratory to full-scale production. The plant couldn’t handle it. The ore proved more difficult to process than first thought, and construction design flaws and engineering problems rose aplenty. In March 2002, Anaconda — now out of the top 100 — defaulted on its debt, and in September 2002 the company posted a net loss of $919 million, then the largest loss from a company ranked outside the top 100. As the company’s flagship project stalled and the share price plummeted, in 2001 Anglo American led a bid to oust Anaconda’s chief executive — one Andrew Forrest, who soon after moved on to another, more successful career as an iron ore magnate, with Fortescue Metals Group. Anglo American sold out of its disastrous Anaconda investment in 2003, leaving Glencore to take full control. In the same year, the company was renamed Minara Resources, which Glencore ultimately took over in 2011.

Engineering risk

Closely related to technical risk is engineering risk, of which Mount Gibson Iron fell foul. The company has the distinction of producing Australia’s highest grade of direct shipping ore, at 65.5 per cent iron. But that didn’t do it much good between 2014 and 2019, when its open-cut mine on Western Australia’s Koolan Island was not only filled with water, but even hosted sharks and crocodiles.

Koolan Island is on the remote Kimberley Coast, 2,000 kilometres north of Perth, and the mine there (first developed by BHP in the 1950s) lies below sea level, separated from the sea by a wall. In 2014, its seawall collapsed, flooding the mine’s main pit. Mining stopped for five years, but insurance payments, plus ongoing cash from its Iron Hill mine inland from Geraldton, kept Mount Gibson in a healthy financial position, and after two years of cleaning up the site, a new seawall was built, enabling mining to recommence. In April 2019, Mount Gibson Iron was back in business, shipping ore. Mine life is a problem at Koolan Island, but at current iron ore prices its high-grade ore is raking it in.

Project risk

Similar to technical and engineering risk is project risk, when a project runs into problems that end up being terminal.

Mining services company Forge Group floated in 2007 at 64 cents a share, and peaked at $6.80 in 2011. But the company collapsed in March 2014, with the shares back down to 82 cents and under the weight of more than $500 million in debt.

Forge’s problems began when it bought power station builder CTEC in 2012. Two power stations that CTEC was building ran into construction problems and cost blow-outs, and Forge Group had to make major write-downs. The power station issues couldn’t be solved and Forge Group had to go into administration.

The administrator’s report was not enjoyable reading for Forge shareholders. It found that Forge over-estimated income, and its labour costs, material costs and work overheads, were much higher than budgeted. The administrator said Forge had collapsed for a combination of reasons, including a reliance on debt for capital funding, an aggressive approach to acquisitions, insufficient risk control measures and failed restructuring.

The administrator’s report also revealed to shareholders that Forge’s largest shareholder, engineering group Clough, raised its concerns that at the time that it bought CTEC, Forge had not done its due diligence on the acquisition properly.

Figure 4-5 shows Forge Group’s share price over its life as a listed company.

Data source: © IRESS Market Technology

FIGURE 4-5: Forge Group share price, 2007–14.

Engineering group RCR Tomlinson, founded in Perth in 1898 and listed in 1951, also fell victim to project risk, which saw it enter voluntary administration in November 2018. The problems began when the company — which specialised in the mining and resources industry — moved aggressively into the solar power arena from 2016 onward. By mid-2017, RCR was telling shareholders that it was ‘positioned for major spend in solar’ and when it announced its interim results in February 2018, it boasted its group revenues had doubled to $940 million with help from its expanding renewable energy portfolio. At that stage, RCR controlled 20 per cent of the market for building solar power farms.

But later that year, it started to emerge just how ultra-competitive that construction market was, as intensifying rivalry for new projects squeezed profit margins. RCR’s strategy of bidding aggressively for solar farms and undercutting its competitors was causing problems. Although its solar portfolio had grown to include more than $1 billion worth of projects, several of them were behind schedule, forcing RCR Tomlinson to pay damages to solar farm developers at the same time it was trying to pay workers and suppliers, draining its available cash.

In August 2018, RCR shocked the sharemarket by announcing a $57 million write-down on two Queensland solar farms and launching a $100 million capital raising. Ground conditions had been misjudged, along with procurement issues and poor information flow to management; more importantly, however, costs had blown out on the fixed-price contracts RCR had signed to build the solar farms. RCR did raise the $100 million — assuring investors that its business was secure — but the write-down was the beginning of the end. In November 2018, the company collapsed when its banks refused to lend it any more money. In December 2018, the administrators reported that RCR had debts of up to $630 million. At its peak in August 2017, shares were trading at $3.50, and the company was valued at almost $1 billion. The shares were trading at 87 cents when the company collapsed; shareholders got nothing. Figure 4-6 shows the share price fall.

Valuation risk

Valuation risk is tied to the price of a share. A company may be well run, profitable, with a conservative balance sheet and part of a stable industry, but the shares can be too expensive to buy. The shares are overvalued.

Valuation risk usually isn’t a problem for investors with a long-term investment strategy because they can afford to wait for the quality of the stock to push the stock past its over-stated value, although a major market slump can force them to extend their holding period beyond what they had expected.

Source: FactSet Prices

FIGURE 4-6: RCR Tomlinson share price, 2014–19.

However, short-term investors have to wait for the price/earnings ratio (P/E) to come back down to earth, which may not fit their investment strategy.

Political risk

Political risk refers to the uncertainty of return from a foreign investment because political or legislative changes in that country may be detrimental to investors’ interests; or, in less stable countries, that coups and political violence can affect companies.

Australian companies, particularly mining and petroleum exploration companies, operate in some of the furthest-flung reaches of the planet, in some cases under regimes considered highly unsavoury and in countries considered unsafe for Westerners.

In November 2019, for example, a convoy of buses containing hundreds of workers at a Canadian-owned mine in the African nation of Burkina Faso — some of them employees of Australian engineering company Perenti Global — was attacked by jihadi terrorists. In the attack, 37 people were killed, 19 of them Perenti employees, and 20 of the company’s employees were wounded. It was a sobering reminder of the risks of operating in unstable regions, and Perenti would hardly have cared about the 11 per cent fall in its share price. The company exited that mining services work contract immediately, but continues to work on three other contracts in Burkina Faso, deeming them to be located in more secure regions.

Africa-focused Australian gold miner Resolute owns and operates three gold mines in Africa — Syama in Mali, Mako in Senegal and Bibiani in Ghana — and concedes that the jihadi terrorist risk has increased in Mali in recent years. While the French Army is working with the Malian government to pacify the country, Resolute says it is taking all the safety measures that it can, including building refuges at the Syama mine.

A more traditional case of political risk involved Australian mining company St Barbara, which operated the Gold Ridge gold mine in the Solomon Islands. Gold Ridge had already been abandoned by its Australian owners once before (in 2000) due to civil unrest, and St Barbara took it over in 2012. The mine experienced incursions into the site, attacks on company vehicles, and vandalism and fire damage to mine infrastructure, only for the workers doing the repair work to then be attacked by locals. Then in 2014, deadly floods shut the mine and threatened its tailings dam, stretching St Barbara’s relationship with the Solomon Islands’ government to breaking point. In 2015, St Barbara sold the mining operation to local landowners for just $100, but not before the problems at Gold Ridge had slashed the company’s value by 96 per cent. (With the Solomon Islands out of its hair, and concentrating on its mines in Australia and Canada, St Barbara has subsequently made a very impressive recovery.)

In early 2016, Australian miner Kingsgate Resources was happily mining its Chatree gold mine in Thailand, which it had discovered in 1995 and started mining in 2001. But in May 2016, the Thai Government announced that all gold mining in Thailand would cease by 31 December 2016 — and Chatree was the only operating gold mine. Kingsgate put the mine on ‘care and maintenance’ in January 2017.

The Thai government’s stated reason for its decision was that the local community was being affected by elevated levels of arsenic and manganese, leading to sickness. Kingsgate countered that extensive testing had shown levels of the naturally-occurring toxins to be similar to other provinces in Thailand. That did not help — the mine was not only closed, but was also expropriated by the Thai government.

Kingsgate had specific ‘political risk’ insurance, but when it tried to claim on this policy in May 2016, the claim was denied. Kingsgate commenced international arbitration proceedings against its insurers in October 2017. In March 2019, the company settled a New South Wales Supreme Court case against its political risk insurers for more than $82 million.

In June 2020, Kingsgate was still trying to get the Chatree mine up and running again, while also taking arbitration measures under the Australia–Thailand Free Trade Agreement to recover from the Thai government losses it claims to have suffered. Kingsgate is also developing its Esperanza gold/silver project in Chile.

Expansion risk

Many companies come awry when they attempt to expand, particularly when moving into another country. Obviously, companies can outgrow the small Australian market, and companies such as CSL, Sonic Healthcare, Ramsay Health Care, IRESS, Computershare, Amcor, Macquarie Group, James Hardie Industries, Cochlear, ResMed and Aristocrat Leisure, to name just a few, have made a very good fist of expanding overseas. Geographic diversification is a good thing.

But many companies have failed.

Examples abound. Casino operator Crown Resorts’ push overseas, from 2004 to 2016, is a case in point. In the heady pre-GFC times, James Packer decided to expand into the gambling hub of Macau. In 2004, Crown entered a joint venture with Melco International Development — the company of Hong Kong and Macau billionaire Stanley Ho — to develop the City of Dreams casino complex in Macau. The joint venture, Melco Crown Entertainment, in which Crown invested $770 million, opened the City of Dreams, Studio City and Altria casino resorts in Macau.

Then, in 2011, Crown bought the Aspinall’s Club in London, a private Mayfair gambling club that it rebranded to Crown London Aspinalls. In 2014, Crown decided to enter the Las Vegas gambling market, buying a prime 7.4-hectare site (and leasing the remaining 6.5 hectares), where Packer planned to build the $2.5 billion Alon casino and hotel project. Then, in 2014, Melco Crown applied for a licence to build a new $US5 billion ($5.4 billion) casino complex in Japan, in time for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.

This expansion was too much. It turned out that competing in Las Vegas and Macau was a bit different from owning an exclusive casino in Melbourne. In October 2016, 17 Crown employees (and two former employees) were arrested in China and charged with illegally promoting gambling; ten (including two Australians) were jailed for nine months. Crown had legitimate fears that it might lose its licence, so it sold out of Macau, halted its development plans in Las Vegas, and shrank the business back to Australia, and its three casinos. (In November 2013, Crown announced it had received approval for the second Sydney casino licence at the Sydney precinct of Barangaroo, where it is building Crown Sydney, scheduled to open in 2021.)

In 2016, Wesfarmers bought the UK/Ireland hardware business Homebase for $700 million, hoping to clone its successful Australian Bunnings concept offshore. Wesfarmers initially told Australian fund managers that it would expand into the British Isles incrementally — but it seemed to get impatient, and changed all the Homebase stores to the Bunnings Australian format straightaway. The business lost sales, key staff and, most importantly, customers, too quickly. In February 2018, Wesfarmers wrote off $1 billion from its investment in Homebase; three months later, it sold the Homebase business for £1, to restructuring firm Hilco Capital.

Another of the biggest bonfires of shareholder value in recent years also took place in the UK. As mentioned in Chapter 3, Melbourne-based law firm Slater and Gordon listed in May 2007, the first legal firm to list in the world, and floated at $1. The stock was welcomed onto the ASX, rising to $1.40 on its first day of trading. With the capital contributed by external shareholders, Slater and Gordon was able to accelerate its acquisition of competitors and consolidation of the Australia market. The firm made progressively larger acquisitions, and in the process consolidated its position as Australia’s largest personal injury law firm, with a market share of about 30 per cent.

These acquisitions grew earnings per share (EPS) significantly, as Slater and Gordon was generally able to buy the smaller law firms at attractive prices. In 2015, Slater and Gordon saw an opportunity in the UK, where the personal injury law market was up to five times the size of that in Australia. Slater and Gordon could increase the size of its business many times over by snatching a 10 per cent or 15 per cent share of that market.

In early 2015, the Australian firm swooped on the professional services division of British law firm Quindells, buying it for $1.3 billion. The debt-funded acquisition, which management hoped to be transformational, very quickly turned into large losses. Quindells was a basket case, in a cash crisis, and its aggressive accounting tactics had been questioned by analysts. In February 2016, Slater and Gordon wrote down the value of this investment by $800 million. By August 2016, the investment had been completely written down, plunging Slater and Gordon to a $1 billion loss for 2015–16, and forcing it to restate its 2014–15 profit from $82 million to $62 million.

The company could not recover from the disastrous acquisition. By March 2017, its banks — including Westpac, National Australia Bank, Barclays and Royal Bank of Scotland, which were collectively owed about $700 billion — sold their debt to distressed debt-buyers (mainly hedge funds), and recapitalised with a one-for-100 share consolidation, virtually wiping out the existing shareholders.

These shareholders had seen their shares peak at $8 a share in July 2015, which valued the company at $2.8 billion. Between July 2015 and April 2017, the share price fell 99 per cent, to 6.8 cents. In its independent expert’s report for the recapitalisation, accounting firm KPMG estimated an implied pre-recapitalisation value for the shares of negative $1.19 to negative $1.65. The shares are still listed in 2020, trading at 90 cents, or 0.9 cents in the pre-recapitalisation currency (see Figure 4-7). At least Slater and Gordon is eking out a profit again.

Currency risk

If a company operates in any currencies other than the Australian dollar, that company has currency risk. Currency risk is a bet that can have a number of outcomes. If the price of your foreign assets rises, you get a capital gain. The important question then concerns the value of those assets in their local currency. Here’s what can happen:

- If the foreign currency strengthens against the Australian dollar (A$), your capital gain is magnified.

- If the foreign currency loses ground against the A$, your capital gain is reduced.

Source: FactSet Prices

FIGURE 4-7: Slater and Gordon share price, 2007–20.

- Conversely, if your foreign assets fall in value, you don’t want the foreign currency to weaken against the A$ because that increases your loss.

- With a falling asset price, you want the foreign currency to strengthen against the A$ to offset some of your capital loss.

Companies try to lessen or negate their currency risk by using the derivatives markets to lock in future receipts or amounts to be spent, at a predetermined rate. This practice of hedging is a form of insurance that can cost money. Hedging doesn’t always work, as with the Sons of Gwalia example, which I discuss in the section ‘Financial risk’, earlier in this chapter.

Specific risk

Risk that is particular to a certain stock is called specific risk. A good example is the biological risk that has affected several listed aquaculture businesses. The first example is Western Kingfish, which was floated on the ASX in July 2007. Western Kingfish operated fish farms at Jurien Bay in Western Australia, where it produced yellow-tailed kingfish. In November 2008, a bacterial infection wiped out 75 per cent of the company’s fish, plunging it into administration.

Fellow fish farmer Clean Seas Seafood had a similar issue. It endured a disastrous period in 2008 to 2012, when it saw fish deaths increase from a normal rate of 15 per cent to about 80 per cent, and it lost 4,000 tonnes of biomass. The company had to liquidate assets, cut workforce numbers in half, and withdraw from international markets (Europe and USA) to survive. It was discovered that the fish-feed was defective in levels of a critical sulphonic acid, taurine, and restocking biomass and slowly re-entering international markets took two years. Death rates have since returned to pre-feed crisis levels of about 15 per cent — and Clean Seas is suing its feed supplier. At least Clean Seas Seafood survived — it specialises in Hiramasa Yellowtail Kingfish, and is Australia’s only commercial producer of the species, and the largest breeder outside Japan.

Tasmanian-based Atlantic salmon producer Huon Aquaculture also demonstrated the risks inherent in aquaculture, this time in 2018–19. A combination of warmer-than-expected water temperatures at its sites and a disease outbreak caused by a jellyfish bloom combined to lower the harvest tonnage by 18 per cent, and slash net profit by 55 per cent.

Huon’s fellow Tasmanian-based Atlantic salmon producer Tassal has also been plagued by environmental issues. As with all animal husbandry, aquaculture has inherent challenges with managing disease and environmental impact, and these challenges have certainly been encountered in Australian aquaculture. But bit by bit, Australian businesses have made clear progress toward best-practice aquaculture — for example, improving the engineering of their ‘pens’ so they can be placed in open ocean, rather than estuaries and waterways closer to land — to the point where the industry is regarded as global leaders in fish and seafood farming and environmental stewardship. The Australian aquaculture industry is on a roll, benefiting from global demand for protein and the twin drivers of a shift to healthy eating and consumers’ need to know that food comes from clean and sustainable sources.

Sector risk

A risk not shared by the market as a whole, but affecting representatives of only one industry, is called sector risk. The mining companies’ health, for example, is dominated by overseas news (especially from emerging markets) and movements in commodity prices and exchange rate movements, requiring investors to keep a close eye on global macroeconomic and geopolitical events.

Fraud risk

Any company with inadequate internal financial controls runs the risk of falling victim to fraud (an economic crime perpetrated against the company, whether by an insider or outsider).

In August 2009, electrical retailer Clive Peeters’ senior accountant defrauded the company of $20 million. She was caught and jailed for five years, while Clive Peeters went into receivership in May 2010, after falling sales and crippling debt of $140 million forced the board to pull the plug. Harvey Norman bought the business in July 2010. The fraud wasn’t responsible on its own for the demise of Clive Peeters, but it certainly contributed.

In 2014, the high-flying chief executive officer of biotech company Phosphagenics, Esra Ogru, was sentenced to six years in jail for creating an elaborate system of fake invoices and credit-card claims to defraud the company of $6 million in a fraud that took place over nine years between 2004 and 2013. After Phosphagenics (which changed its name to Avecho Biotechnology in May 2019) alerted the ASX in July 2013 that ‘invoicing and accounting irregularities’ had occurred, the share price lost 82 per cent.

In 2015, the former chief executive and former chief financial officer of generic drug maker Sigma Pharmaceuticals (which changed its name to Sigma Healthcare in March 2017) pleaded guilty to falsifying the company’s accounts in 2009 and 2010. The court heard that Sigma’s accounts overstated the company’s income and revenue by $15.5 million, inventories by $11.3 million, and net profit by $9.6 million.

Sigma’s financial difficulties during 2009 and 2010 had already resulted in the company agreeing to pay shareholders almost $60 million in 2012, to settle a class action brought by disgruntled investors. The class action rested on the company predicting that it would record modest profit growth when it was conducting a $300 million capital raising in September 2009; six months later, Sigma shocked the market by revealing a $424 million write-down that led to a $389 million loss for the 2009–10 financial year (ending 31 January, 2010).

That unexpected loss — announced in March 2010 — saw the sharemarket halve Sigma’s market value in a day.

Fraud can even come from outside the company. In January 2013, coal miner Whitehaven Coal lost 9 per cent of its market value after an anti-coal activist issued a fake press release stating that ANZ Bank had withdrawn its $1.2 billion loan to help Whitehaven build a new coal mine because of environmental concerns. Whitehaven shares lost about $280 million in market value in a matter of minutes.

Agency risk

Agency risk refers to the risk that management and the board (the investors’ ‘agent’) may act in the best interests of the agent rather than the investors. An obvious example is when boards approve ridiculous salary packages for managers, but agency risk can manifest itself in quite a number of areas:

- Senior management paying themselves disproportionately to the earnings of the business, and their own performance

- Management making investment decisions that might maximise the short-term earnings and/or share price performance to realise incentive payments, even if those investment decisions are not in the long-term interests of shareholders

- Management increasing corporate expenses, including significant employee perks

- Management focusing on growing the size of the business, rather than its profitability

- New management tossing out the garbage early in their term of office — for example, booking big provisions and write-downs in the early years, so as to demonstrate improved performance, and make earnings targets easier to reach in later years, thus achieving bonuses

- Management making decisions on mergers and/or acquisitions (either as the target or the acquirer) that result in significant personal benefits, when the benefit for shareholders is far less apparent

An increasing trend in recent years has been professional fund managers looking to lessen agency risk by tilting toward businesses where the agency risk is naturally lessened; typically where the business (although listed) is still largely founder-led, or where the CEO and/or board members have significant ownership. These investors are voting with their feet by seeking out companies with much tighter alignment between management’s and investors’ interests.

Examples of companies where the founders — or their families — are still heavily involved at management level include plumbing supplies group Reece (the Wilson family), retail business owner Premier Investments (Solomon Lew), Flight Centre (chief executive Graham Turner is one of the three founders, and the other two founders, Bill James and Geoff Harris, are still major shareholders), enterprise software group TechnologyOne (founder and executive chairman Adrian Di Marco), TPG Telecom (founder and executive chairman David Teoh), Nick Scali Limited (the Scali family) and Event Hospitality (the Rydge family). Other companies where the founders remain big shareholders include Fortescue Metals Group, Computershare, Magellan Financial, Mineral Resources and Pro Medicus.

Non-financial risk

Non-financial risk can come from such areas as product liability, occupational health and safety, human resources and security issues. Political, environmental and market changes can also be termed non-financial risk. Although these elements don’t have specific dollar values, they eventually have a direct impact on financial risk.

Climate-change risk

These days, companies are expected to monitor and report to shareholders on their exposure to material economic, environmental and social sustainability risks, and what they are doing to manage these risks. In particular, climate-change risk has become an important risk to be disclosed, and every regulator with which Australian listed companies deal has spelled out for them what is expected.

In the last four years, listed companies have had the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), the Australian Accounting Standards Board (AASB), the Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (AUASB), the Council of Financial Regulators (CFR) and the ASX — and even the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) — all emphasise the need to improve climate change risk disclosure.

The framework that has become increasingly prominent globally — and has been adopted by Australian regulators — is that of the Taskforce on Climate Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), a body established by the Financial Stability Board of the G20 nations.

The TCFD recommendations set out the kind of information that must be analysed and disclosed in order to truly and fairly represent (and enable assessment of) the impact of climate-related risks on companies’ financial positions and prospects, in a consistent form, such that investors, lenders and insurers can base decisions on it. The TCFD contemplates not only the disclosures themselves, but also the risk metrics and targets, strategy and governance processes within which climate risk issues are managed.

In August 2019, ASIC rewrote its Regulatory Guidance on market disclosures for both prospectuses (RG228) and annual report operating and financial reviews (RG247), describing climate change as ‘a systemic risk that could have a material impact on the future financial position, performance or prospects of entities’. ASIC also now includes climate risk in its list of factors that may result in non-financial impairment.

In the fourth edition of the ASX’s Corporate Governance Council’s Principles and Recommendations — which took effect for an entity’s first full financial year commencing on or after 1 January 2020 — the ASX explicitly referred companies to climate-change risk as part of Recommendation 7.4, which deals with material exposure to ‘economic, environmental and social sustainability risks’.

Recommendation 7.4 encourages entities to both consider whether they have material exposure to climate change risk by reference to the TCFD recommendations and, if they do, make the disclosures recommended by the TCFD.

Reputation risk

Climate-change risk is just one risk that comes under the Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) umbrella, which refers to how a company is performing in terms of the environmental, social and governance aspects of its operations — and how seriously it takes these aspects. ESG is a broad topic, but covers areas such as environmental impact; ‘human capital’ issues, such as gender and ethnic diversity in the composition of board, management and staff; the social and health impact of the company’s operations; and the quality of the governance by which the company is structured and operates.

ESG risk is an example of risk that is incurred by the company’s conduct, which can affect its reputation. And with the rise of social media, companies have had to get used to the idea that any reputational risk is likely to be on social media within minutes. Cyber-risk (the risk of having data compromised) and supply-chain risk (the risk that other companies in their supply chain have practices they might not know about, such as modern slavery) are other, newer risks that companies run; terrorism risk is another.

How good a corporate citizen a company is — with respect to all of its stakeholders, and measured by ESG factors — now ranks as one of the most important ongoing tasks for management. Being measured solely on financial metrics and praised as a good investment that rewards shareholders is no longer good enough; companies are now seen as having a ‘social licence to operate’, that they must maintain, and which, by implication, can be withdrawn at any time if the community feels let down by the company’s actions.

The problem of subjectivity is shown by the case of coal miner Whitehaven Coal, which, as a producer of coal, is accused by environmental groups of not having a social licence to operate. But Whitehaven Coal turns that around by arguing that hundreds of millions of people in Asia and other parts of the world do not have electricity, and that it supplies the coal that brings electricity — and thus, the ability to function better economically — to some of these people. That argument shows that the social licence to operate is in the eye of the beholder.

Some companies have been slow to respond to ESG allegations, believing that it does not pay to rock the boat. When copper miner Sandfire Resources read in the media in 2014 that Australian National University (ANU) was selling out of its shares in the miner (and six other resources companies) because they were ‘not socially responsible, and doing harm’, according to the university’s then vice-chancellor, it was at first annoyed, and then — when the ANU’s decision was reported on the front page of the Wall Street Journal — it was angry.

Research firm the Centre for Australian Ethical Research (CAER) had been commissioned by the ANU to do proprietary research into the environmental, social, governance and ethical performance of the companies in its portfolio, and it recommended that Sandfire be dropped. Sandfire believed that what CAER had said about it was incorrect, out of date and misleading.

Sandfire brought a case against CAER in the Federal Court, which it discontinued in April 2015, once CAER issued a statement saying that the ESG ratings and reports on Sandfire it provided to ANU were ‘deficient and inaccurate’ and that ‘significant aspects of the research, conclusions and ratings were drawn from incomplete and out-of-date information’.

Sandfire’s CEO said that the stakes were too high to let the allegations slide. The company was trying to gain permits for a copper project in the US and letting the allegations stay on the public record could prejudice that. But more worrying to the company was that it did not want the rest of its shareholders and stakeholders to believe that it was not prepared to defend its ESG record.

On the other hand, clear cases of companies not adhering to ESG factors can greatly cost them. One of the highest profile examples is German car giant Volkswagen, which was discovered in 2015 to have cheated on its cars’ pollution emission tests. The scandal cost VW US$33.3 billion (A$51 billion) in fines, penalties, financial settlements and buyback costs, but what would have hurt the company more was that it halved the share price — and trashed its reputation.

Closer to home, financial services heavyweight AMP had a horror time in the Australian government’s Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry in 2018. As if two decades of poor performance were not enough, AMP shareholders had to endure the painful sight of a string of executives, including then-chief executive officer, Craig Meller, and head of wealth solutions, Paul Sainsbury, admitting to various kinds of corporate misconduct, including charging customers fees where no service had been provided, and even continuing to charge deceased customers despite knowing they had died; breaching criminal provisions in the Corporations Act; and intentionally misleading the corporate regulator, the Australian Securities & Investments Commission (ASIC), for almost a decade.

Figure 4-8 shows what the sharemarket thought of AMP’s appearances at the Royal Commission — the company’s already poor reputation headed to the toilet. (Mr Meller’s and Mr Sainsbury’s appearances before the Royal Commission are indicated at points (1) and (2).)

Source: FactSet Prices

FIGURE 4-8: AMP share price, 2017–20.

Information risk

Information risk is when investors who are buying shares rely on such published information as a company’s prospectus, announcements to the stock exchange, annual reports and brokers’ research documents. All of these documents carry legal disclaimers that say, in a variety of ways, that they can’t be relied upon, even if audited. As a wary investor, you need to research information from different sources to lessen the impact of information risk.

Avoiding the Turkeys

You can use a variety of techniques to assess whether any of the shares in your portfolio are at risk. The health checks you can apply to shares can be either fundamental or technical. Technical analysis involves charting share prices and trying to extrapolate from past trends. Fundamental analysis looks at a company’s financial performance — cash flow, balance sheet, revenue, earnings and dividends.

Using technical analysis

Investors who follow charts like to identify support levels for stocks — that is, prices at which, in the past, the stock has turned upward. A stock falling through a support level on a chart is enough for most technically oriented traders to pull out of a company’s shares. Even if you don’t wholly trust technical analysis, you’ll find that often — especially with the aid of that precious investment tool, hindsight — the charts tell a story of trouble before the news gets out to the market.

Watching cash flow

When you review a company’s performance, always reconcile cash flow — the difference between revenue and outgoings as depicted in the cash flow statement — with reported profit. Those are the only earnings that matter. If you do this annually, you need to look beyond the company’s reported result to the improvement in its balance sheet. Deterioration in cash flow (or, worse, cash inflow becoming cash outflow) is a signal that the risk has become higher.

Charting dividend changes

A lowered dividend, or a dividend that is only maintained at the previous year’s level, is also a danger signal. Companies that pay a dividend go to almost any lengths, including borrowing, or dipping into their reserves, to maintain that dividend.

Gauging who’s selling — or buying

Heavy institutional selling (when the super and managed funds sell their shares) is an indication that something isn’t right with a company. The institutions follow a stock more closely than you do and know more than you do. If they’re queuing up to sell shares, it isn’t a good sign.

The exit of institutional investors from the share register of Sons of Gwalia after a profit warning in July 2004 was a sign that the market was concerned at the company’s direction — concerns that were borne out. Your broker is able to provide this kind of information so you can protect your portfolio.

The directors of a company know its prospects better than anyone. These days, following all the announcements a company makes is relatively easy and directors must notify the sharemarket if they sell shares. Change of Director’s Interest Notices announced to the ASX disclose when directors are selling securities in a company. This will be a signal for institutional investors to at least investigate the reason for the sale.

Insider selling is quite common, and investors often notice that it can precede company problems and steep share price declines. In recent years, examples include selling at Aconex and Bellamy’s Australia (when it was listed), Brambles, Healthscope, Sirtex Medical, Vita Group and Vocus Communications.

Insider selling can also occur in the best-performing companies, and at prices where the insiders forego considerable upside. Qantas CEO Alan Joyce sold $7 million worth of shares in August 2016, at $3.29 — prior to the COVID-19 crash, Qantas shares were trading at twice that price. Outgoing Aristocrat Leisure CEO Jamie Odell sold $12.6 million worth of shares in December 2016, at $11.94 — in the case, prior to the COVID-19 crash, Aristocrat shares were trading at more than triple that share price.

Insider share movements can also go the other way. Late in 2019, the new NAB CEO, Ross McEwan, showed his commitment to his new employer through an on-market purchase of 5,000 shares at $25.459. Spending $127,295 of his own coin would have come as a welcome vote of confidence for NAB shareholders, who had watched their company’s share price slide from $41.46 in 2007. Sadly for McEwan, after the COVID-19 crash, his investment was soon 35 per cent underwater. At least the shareholders know that their CEO is hurting, too.

In contrast, a new shareholder becoming a substantial shareholder is a sign that someone likes the company — whether as an investment or, in some cases, as a potential acquisition. Once an entity is a substantial shareholder, any subsequent increase of 1 per cent in its stake must be disclosed to the ASX. (They must also announce each 1 per cent decrease in their holdings.) The law prevents individuals or entities from acquiring over 20 per cent in a company without a formal takeover bid, but the ‘creep rule’ provision’ of the Corporations Act is an exemption — it states that an investor that has moved to 19 per cent of a company is allowed to buy an extra 3 per cent of the company every six months (even if they creep to holding 20 per cent or more). However, they have to wait another six months before making any formal acquisitions.

The highest risks bring the highest rewards. If you place your money on a single number at the roulette table, you have a 1 in 36 chance of your number coming up. That’s why the table pays $35 for every dollar you put on it. As anyone who plays roulette can tell you, the 35 to 1 payout is a wonderful win to have early in the night. However, if the hour is late and you’re chasing a win to get out of trouble, your odds may seem more like a 1 in 360 chance.

The highest risks bring the highest rewards. If you place your money on a single number at the roulette table, you have a 1 in 36 chance of your number coming up. That’s why the table pays $35 for every dollar you put on it. As anyone who plays roulette can tell you, the 35 to 1 payout is a wonderful win to have early in the night. However, if the hour is late and you’re chasing a win to get out of trouble, your odds may seem more like a 1 in 360 chance. Time also manages risk, by minimising it psychologically. As you come to understand the returns a share portfolio can generate over time, you begin to relax about short-term fluctuations.

Time also manages risk, by minimising it psychologically. As you come to understand the returns a share portfolio can generate over time, you begin to relax about short-term fluctuations. Companies may feel that the concept of a ‘social licence to operate’ is highly subjective, and the ASX seemed to tacitly concede this in 2019 when — to the surprise of some — it dumped a proposal to include reference to a social licence to operate in its updated corporate governance guidelines referred to in the preceding section. The new guidelines did refer to a companies’ need to maintain their ‘reputation’ and ‘standing in the community.’

Companies may feel that the concept of a ‘social licence to operate’ is highly subjective, and the ASX seemed to tacitly concede this in 2019 when — to the surprise of some — it dumped a proposal to include reference to a social licence to operate in its updated corporate governance guidelines referred to in the preceding section. The new guidelines did refer to a companies’ need to maintain their ‘reputation’ and ‘standing in the community.’ A company cuts or suspends a dividend only under extreme financial duress. You need to follow the dividend returns of companies in your portfolio and know when your dividend is under threat, despite the spin-doctoring in company announcements.

A company cuts or suspends a dividend only under extreme financial duress. You need to follow the dividend returns of companies in your portfolio and know when your dividend is under threat, despite the spin-doctoring in company announcements.