Chapter 3

Developing an Investment Strategy

IN THIS CHAPTER

Enjoying the luxury of time

Enjoying the luxury of time

Defining your investment goals

Defining your investment goals

Timing your trading

Timing your trading

Understanding what changes the price of a share

Understanding what changes the price of a share

Devising a sharemarket investment strategy means asking a basic question: ‘Why am I buying this share?’ If the answer to the question is ‘My brother-in-law told me at a barbecue on the weekend that this share was about to go through the roof’ … then you’re gambling.

But if the answer to the question is

- I’ve researched this unloved stock pretty thoroughly and I think the company is making a good product that doesn’t have much competition.

- I’m fairly confident the company has solved the problems that caused the share price to fall and I believe its earnings are going to grow.

- This share fits all my criteria for buying, and I’m happy to buy it at this price …

… then you’re investing, and developing your investment strategy is what this chapter is about.

Investing is a simple concept. You store buying power in the form of money today for future use. What you’re trying to do when you invest is to conserve the capital that you’ve earned and saved, and to make it grow. To invest successfully, you need to put your money where your investment can generate a return ahead of inflation (the rate of change in the cost of living), so that the purchasing power of your capital is at least conserved. Naturally, you want to earn a return above the inflation rate so that your invested money is actually growing in value.

Getting Rich Slowly

Investing in shares requires patience. If you attempt to compress the wealth-creating power of the sharemarket into weeks or even days, you’re asking for trouble. Occasionally — for example, amid the technology boom of 1999 to 2000 or, more recently, the over-confident market of 2019 — Australians forget this rule and try to participate in the spectacular short-term capital gains available on the sharemarket.

Giving yourself time in the market

Only after one of these periodic bouts of insanity do investors remember how the sharemarket really creates wealth — slowly, over years. Since 1900, according to AMP Capital, the All Ordinaries Accumulation index has delivered a total return of 11.5 per cent a year; much better than Australian bonds (5.9 per cent a year) or cash (4.7 per cent a year). If you’d had an astute investor in your family tree who’d put $100 in the sharemarket on your behalf in 1900 (in the equivalent of the All Ordinaries Index) and left it to accumulate, with all dividends reinvested, that investment would have grown to more than US$48 million (A$48.2 million) by now.

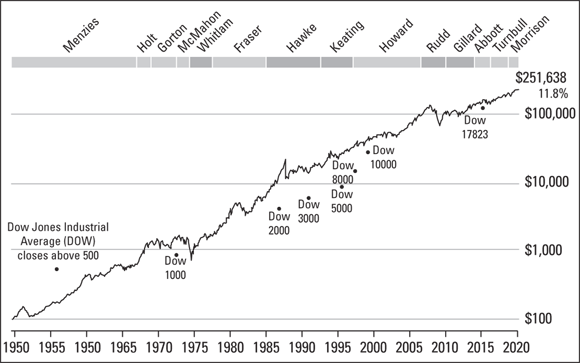

Since 1950, says research house Andex Charts, the S&P/ASX All Ordinaries Accumulation index (which counts dividends reinvested as well as capital gain) has delivered a return of 11.8 per cent a year, enough to turn an investment of $100 in 1950 into $251,638 (see Figure 3-1). That compares to 7.7 per cent a year for bonds, 6.2 per cent a year for cash, and inflation at 4.9 per cent a year.

Source: Andex Charts Pty Ltd

FIGURE 3-1: The growth of a $100 investment in the sharemarket over 70 years.

Not many people have an investment term of 100 years, or even 50 years. Most investors are active for 20 or 30 years. The good news is that in the past three decades, shares have actually outpaced their century-long average return because of economic growth and falling inflation. Over the 30 years to the end of 2019, says Andex Charts, the S&P/ASX All Ordinaries Accumulation index has earned investors 9.2 per cent a year; over 20 years the return is 8.3 per cent a year. This steady rise in share price is the key to sharemarket investing.

Although share prices are extremely volatile, share dividends are far less so. When you buy a share, you’re buying a portion of the future earnings of that company, part of which comes to you as a dividend, and part of which goes into retained earnings. Over time, this process of building equity also results in capital gain.

You can’t expect a return of 11.8 per cent on your share portfolio next year or the year after that, but the pattern of growth should remain similar even though the market may lose value during any given year. Those downward blips on the graph represent risk.

Any sharemarket index has a very high degree of ‘survivor bias’. In 2019, advisory firm Stanford Brown crunched the Australian numbers and estimated that the 2,300 companies listed on the ASX represented just 6 per cent of the companies that had raised from investors and listed on an Australian stock exchange since the early 1800s. Moreover, only an estimated 580 of those listed companies were making money — meaning that only about 1.5 per cent of all the companies that have ever listed in Australia managed to survive and build a profitable business.

Where did the 94 per cent of companies that had not survived go? Stanford Brown estimated that up to 1,000 of them, or about 3 per cent, were taken over by other local companies. Another 200 or so were taken over by foreign companies. The rest simply failed and disappeared, or were mopped up at very low prices.

Compounding magic

You’re taught about compound interest at secondary school, but you probably didn’t pay too much attention to it. A quote commonly misattributed to Einstein is that compound interest is ‘the greatest mathematical discovery of all time’.

Here’s how compound interest works:

- Interest is earned on the original sum invested.

- Next, interest is earned on both the original sum invested plus the first round of interest.

- Then, interest is earned on the original sum and all the interest so far accumulated, and so on over the period of the investment.

Over time, compound interest produces impressive growth. An investment earning 7 per cent a year will almost double in ten years. When the time required for compound interest to really get cracking is not available — for example, you want your investment to double in less than ten years — then you need to be a less conservative investor. If you want to shorten the time for your investment strategy and still double your money, you need to draw a deep breath and take more risk.

Starting with Strategy

Self-knowledge is the key to setting up your investment strategy. You have to know where you’re going before you set out on the journey. You already know that time, patience and diversification load the dice in your favour when approaching sharemarket investment.

- Income investor: Someone looking for share investments that can pay a wage

- Retiree: The most conservative and risk-averse income investor

- Straight investor: A wealth builder

- Speculator: An impatient wealth builder willing to take risks

- Trader: An impatient wealth builder, prepared to spend a lot of time watching the market for opportunities

Each of these types of investor faces different challenges. You can determine which type of investor you are and then choose the strategy that serves your needs. Retirees invest their money conservatively in order to guarantee returns. Gamblers — speculators — take very risky short-term bets to make a quick capital gain. Straight investors stick to the higher quality industrial stocks, the blue chips, for long-term growth.

Spreading the risk

Diversification, which you can read more about in Chapter 5, is a popular investment strategy. The idea is to spread the funds you have available for investment among different assets in order to distribute and, hopefully, contain the risk.

The other side of diversification is that it can lower performance because it introduces more elements; but for many investors, containing the risk of sharemarket investment is more important.

Diversification isn’t just a protective measure; it also allows you to generate a higher rate of return for a given level of risk. You can achieve reasonable diversification of a share portfolio with as few as ten stocks. Buying up to 15 different stocks adds to the diversification, but beyond that number, monitoring your portfolio of stocks properly is difficult. A good diversification strategy for ten stocks means not having more than 15 per cent of your portfolio by value in any one stock.

A share portfolio can be spread around and still not be properly diversified. You need to buy shares from market sectors that balance each other, so if one part of the portfolio is performing poorly, other shares will be doing better. For example, an investor who bought shares in CSL and subsequently in REA Group balanced global healthcare with an investment in real estate websites in Australia, Europe, Asia and the US. The same investor buying shares in diversified miner and petroleum producer BHP would give the portfolio an interest in industries unrelated to the other two.

Setting your goals

What are you hoping to do with your share investments? Are you saving for a deposit on a house? Your children’s school fees? Retirement income? Or, are you simply trying to maximise capital growth? All these goals pose different time constraints and risks. After you’ve settled on the type of return you’re after — a decision that also helps you decide what type of investor you are — you can decide which shares can deliver the results and which shares you can rule out. If you’re a straight investor, look for companies that promise long-term capital growth. If you’re a retiree, you may be interested in a strong and sustainable flow of fully franked dividends.

Setting your time frame

How long can you give the investment? The longer you give your investments, the better. However, if you need short-term income, you have to be more aggressive in your wealth creation strategy. You may have to take on some speculative shares that carry more risk but promise greater return. Unfortunately, this means that you’re in for some scary periods because you’re unable to use the great risk minimiser — time. Deciding how much time you have helps you determine what type of investment strategy, and therefore shares, you require.

Setting your risk tolerance

After you know your goal and your time period for investing, you can begin to understand your risk profile. What is the maximum level of risk that’s acceptable? How comfortable will you be if your investment loses 20 per cent of its value — or half? If you can’t handle that sort of volatility, you may need to adjust your goals and the time frame. Unfortunately, risk comes with the territory. If you want to invest in the sharemarket, as opposed to other asset classes, it pays to be realistic about the level of risk that you can tolerate.

If you want your share investments to fund your children’s education, or your own retirement, you have to be reasonably risk-averse. That doesn’t mean sticking to government bonds or term deposits, because those assets simply wouldn’t create the capital growth that you need. Being risk-averse as a share investor means concentrating on those companies with the most reliable long-term track record of earnings and dividend growth, rather than speculating in a minerals explorer or drug-development hopeful that has not yet made a profit. Those kinds of stocks may make a lot of money, but as a risk-averse investor you can’t afford to take that bet. You need to be in stocks where the compounding of a growing earnings stream is a much surer driver of capital growth.

Setting your financial needs

Do you have tax and liquidity issues? If you have short-term financial needs, you may have to face the prospect of unravelling your strategy. If the money you plan to invest in the sharemarket is money that you really can’t afford to lose, maybe you need to rethink what you’re doing in the first place.

Although the sharemarket offers a better prospect of capital growth than a term deposit in a bank or a government bond, it’s not as safe a place to put money that you can’t afford to lose. The sharemarket is much better suited as a place to invest money that you can afford to lose — and leave for a long time — to give your investment the best possible chance to make money for you.

Buying and Holding

A straightforward strategy for share investment is to buy and hold. You buy a portfolio of stocks and hold on to them for the long term.

One more element to the buy-and-hold strategy exists and that is ‘sell’ (although the strategy would then become buy, hold and sell). If you never sell a stock, the wealth the stock creates exists only on paper.

Philip Fisher, in his classic book Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits, states: ‘If the job has been done correctly when a common stock is purchased, the time to sell it is — almost never.’ This approach is fine if you want the value of your shares to be part of your estate to be passed on to your heirs, but plenty of people look at successful buy-and-hold share investing as a way to fund a happy and fulfilling retirement, free of financial worry. If that’s what you’ve decided, selling shares to raise money is fine if you plan carefully.

For the buy-and-hold strategy to work, you have to choose your stocks carefully. Obviously, you want more stocks in your portfolio to be like Westfield (sadly, gone from the Australian sharemarket) or CSL. (If you manage to pick the next Westfield or CSL, you don’t have to worry about the rest of your portfolio. See the sidebar ‘The miracle of Westfield’ for more information on this stock, and the later section ‘Timing for the long run’ for more on CSL.) Buy and hold doesn’t work with every stock. For example, it doesn’t make sense to buy shares in building materials companies, such as CSR, Boral, James Hardie Industries and Adelaide Brighton, and just put them in your bottom drawer. The Australian building industry is highly cyclical because it’s based on the ups and downs of the economic cycle. The industry has taken steps to rectify this by moving into other countries, but it remains vulnerable to Australian construction cycles.

A range of shares exists that’s too volatile to be part of a stable portfolio that doesn’t change over a long period. For example, property developers and contractors don’t really suit this purpose because their activities depend on interest rates, which can fluctuate. The same used to be said for the big mining shares, such as Rio Tinto, BHP, Fortescue Metals and Alumina, because they are linked to the ups and downs of commodity prices, which are linked to the economic cycle of the major Western economies. However, this perception prevailed before the Chinese economy, with its huge appetite for raw materials, took off in the late 1990s to early 2000s, on its way to becoming the second-largest economy in the world. Australia’s miners are still exposed to the global economy, but the driver of the global economy is China.

Timing your strategies

With the right timing, you can make money on the sharemarket. You can buy a share, sell it for a gain, watch it fall all the way back and buy it again, and then begin the whole process over. However, this sort of transaction is hard to do because it involves forecasting. Predicting the points in the sharemarket at which a top or a bottom is reached is virtually impossible.

Nobody rings a bell at the top, or the bottom, of the market; these highs and lows can usually only be seen in hindsight. For example, in March 2009 when the Australian market finally found a bottom after 15 months of falling — or even after a much quicker fall such as in February to March 2020 — going back into the market seemed the worst thing to do, because the headlines were uniformly gloomy and the prevailing sentiment was terrible.

Studies from the USA, Canada and Australia show that professional investors and fund managers don’t always make money from attempting to correctly time their moves. In fact, some of these experts can make big mistakes. Knowing when to time risk can be a big problem for market timers; they often fail to predict a turning point. An example is when market timers pull their investments out of the market, believing that the market will fall, and then a sudden rally leaves them little time to get back in. The problem for aspiring market timers is that very few investors, even professional ones, can accurately predict the behaviour of the market.

A further problem is that if you buy and sell an investment several times, you have to take this activity into account when adding up your profit. Your profit can be eroded by transaction costs, meaning if you sell the shares and remake the initial investment several times, your capital gain still may not be as good as that made by the investor who buys once, holds and sells.

Trading on your portfolio

Even if you invest with a long-term view, you can also act in the short term. You may think that having chosen 10 to 12 stocks for a portfolio, you’ll still be holding them at the end of your predetermined investment period. Sometimes, however, you have to change your strategy.

If some of the shares in your portfolio are performing poorly, or if you change your view on the quality of the business, don’t hesitate to turf them. The shares in your portfolio are there to do a job, which is to make money for you. If circumstances change, and they can’t do the job, cut them loose. Set a level of loss beyond which you’re not prepared to follow — say, 15 per cent. Set a profit limit, too, beyond which you’re not prepared to follow. Be ruthless with yourself and don’t regret the profits you didn’t get. As the saying goes, you don’t go broke taking a profit. Of course, long-term investors may choose to use a short-term price fall to buy more shares.

Whatever strategy you choose, stick to it. If you adopt the buy-and-hold approach, don’t allow yourself to be panicked out of a shareholding. If your strategy is to maximise your returns through active trading, make sure you have your ground rules in place on when to buy and sell. Don’t be seduced by emotion — whether it be fear or greed!

Timing for the long run

Time works to minimise risk. In the short term, shares are the most likely of the asset classes to fall in price — in the words of the pros, to ‘generate a negative return’. Statistically, the sharemarket is more likely to record a negative return in a given year than any other asset class. In the longer term, however, shares are the most likely to generate a positive return.

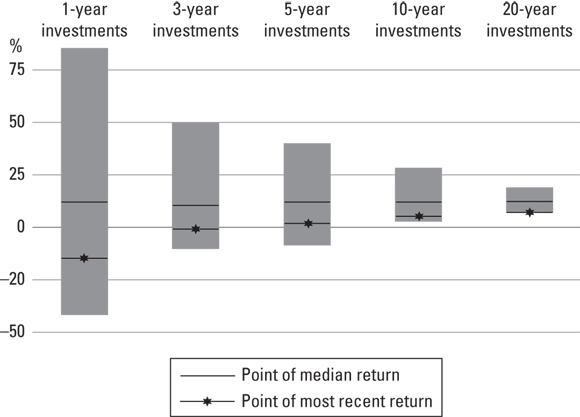

Andex Charts has calculated the risk and return from the Australian sharemarket (as measured by the S&P/ASX All Ordinaries Accumulation index) over the period 1 January 1950 to 31 December 2019, measured over one, three, five, ten and 20 years, with investments made at month ends. Andex measured 829 one-year periods, 805 three-year periods, 781 five-year periods, 721 ten-year periods and 601 20-year periods (see Figure 3-2).

Source: Andex Charts Pty Ltd

FIGURE 3-2: How time tempers the risk and return on shares.

The one-year investments showed great volatility, with a best return of 86.1 per cent (year to 31 July 1987) and a worst performance of minus 41.7 per cent (year to 30 November 2008). The average gain was 13.5 per cent, but more than one in five (22.4 per cent) of the short-term investments showed a loss.

When the investment period was extended to three years, the probability of success rose to more than 90 per cent. The best return was 50.3 per cent a year (three years to 30 September 1987), while the worst performance was minus 10.9 per cent a year (three years to 31 December 1974). The average gain was 12.2 per cent a year.

The average return over five years was 12.2 per cent a year, with a best return of 40.4 per cent a year (five years to 31 August 1987) and the worst performance being a loss of 9.2 per cent a year (five years to 31 December 1974). The risk of loss in the five-year periods was still present, though, with a handful of the periods (4.4 per cent) failing to make a positive return.

By the time the investment term was extended to ten years, all investment periods showed a positive return. The best result was 28.7 per cent a year (ten years to 30 September 1987), the worst was 2.9 per cent a year (ten years to 30 September 1974) and the average gain was 12.2 per cent a year.

Over 20 years, the average investment in the sharemarket showed a gain of 12.4 per cent a year. The best was 18.9 per cent a year (20 years to 30 September 1994), while the worst came in at 7.9 per cent a year (20 years to 31 December 2018.) The sharemarket doesn’t come with a capital guarantee, but on the statistical evidence gleaned from seven decades, a ten-year investment in the sharemarket is as good as guaranteed.

Interestingly, when this data was updated to take in the COVID-19 crash, it barely changed. Even though the Australian sharemarket endured a 38 per cent slump at one point in the March 2020 quarter — which took it to a 12-month loss at 31 March 2020 of 15 per cent — adding another three one-year measurements to the figures did not change the average rolling 12-month average return, at 13.5 per cent. Returns were positive 77.5 per cent of the time.

At 31 March 2020, the three-year return was a loss of 0.7 per cent a year; the five-year return was 1.5 per cent a year; the ten-year return was 4.8 per cent a year; and the 20-year return was 6.8 per cent a year.

Share prices can and do fluctuate alarmingly. In the COVID-19 Crash, some of the price falls in the S&P/ASX 200 included the following:

- Flight Centre –74.9%

- Afterpay –74.8%

- Credit Corp –73%

- Webjet –72.2%

- oOh! Media –70.4%

- Corporate Travel Management –69.5%

- EML Payments –69.5%

- Challenger –67.8%

- Oil Search –67.8%

- Qantas –67.1%

In that kind of heightened volatility and extreme nervousness, shares can plunge alarmingly — and indiscriminately. Even the market’s top ten behemoths by market value were pounded mercilessly in February to March 2020:

- CSL –29.2%

- Commonwealth Bank –41.3%

- BHP –43.2%

- Westpac –55.2%

- National Australia Bank –56.0%

- ANZ Banking Group –51.9%

- Woolworths –20.3%

- Wesfarmers –37.3%

- Macquarie Group –53.8%

- Transurban Group –44.7%

Those are the kinds of falls that can immolate several years of patient appreciation. On the plus side, however, news of a takeover bid, or a mineral discovery, or a successful drug test result can send a share rocketing. Any share that you own can jump by 25 per cent tomorrow, but it can just as easily suffer a drop of the same proportion.

If you get in on the ground floor, the rewards can be spectacular. For example, the former Commonwealth Serum Laboratories (now CSL Limited) — the largest Australian stock by value — is one of the all-time great stories of the Australian stock market. When the Australian government floated CSL on the stock market in June 1994, it clearly had no idea what it owned.

CSL was floated at $2.30, raising $300 million for the government (it is now valued at $136.8 billion.) After a three-for-one share split in 2007, the float price was effectively 77 cents a share. Each of those shares now trades at a staggering $310.00. Add the $22.08 that has been paid in dividends to the share price, and the original shareholders have made more than 400 times their investment. To have generated $1 million out of CSL, all that an investor buying in the float had to put in was $2,483.

Commonwealth Bank was also sold onto the sharemarket by the Australian government, in its case for $5.40 a share, back in September 1991 (subsequent tranches sold for $9.50 and $10.00). Investors who backed the original float now have shares that trade for $58.90 (down from their high of $91.00 in February 2020), meaning they have multiplied their investment by close to 11 times. But they have also received $65.99 in dividends along the way, which takes their gain to 23 times. Financial newsletter Motley Fool takes this even further, calculating that an initial investor who reinvested every dividend in more CBA shares would have made 73 times their money.

Property websites operator REA Group was floated (as realestate.com.au) in December 1999 at 50 cents; at $91.99, shareholders have made 184 times their money. And if you were one of the prescient investors who snapped REA up for 4.9 cents a share in September 2001, when the sharemarket in its wisdom judged that the business wasn’t going so well — you’ve multiplied your investment by 1,877 times.

The share market is full of these kinds of stories. Indeed, investors often talk about the hunt for the almost-mythical ‘ten-bagger’ — a stock that returns ten times the investment — but 20-, 30-, 40-, even 50-baggers are everywhere, with the important caveat that investors only know this with the benefit of hindsight. And ‘baggerhood’ of any multiplication, once achieved, is not necessarily permanent.

Macquarie Bank (now called Macquarie Group) came to the share market in 1996 at $6.50 a share. It went as high as $98.64 in May 2007 — becoming a 15-bagger — but the GFC knocked it back to $15 in March 2009. Amazingly, investors got another chance — the company’s impressive post-GFC turnaround saw it peak at $148.58 in February 2020 — just failing to become a ten-bagger for the second time (rising by 9.9 times). With dividends included, however, it made it.

In the midst of the GFC, travel agency business Flight Centre traded as low as $3.90, but by August 2018 was $61.56. With travel trashed by COVID-19, however, Flight Centre has slumped back below $10.

But, sadly, at any time some companies are always heading in the other direction. In May 2007, law firm Slater and Gordon floated on the stock exchange at $1.00, as the world’s first legal practice to list. At its peak in April 2015, the shares were $8.00; however the company blew up through over-expansion and the shares fell to be virtually worthless — after a one-for-100 consolidation, the still-trading shares are down by 99.9 per cent from the high. (See Chapter 4 for more on the rise and fall of Slater and Gordon.)

Surfwear group Billabong International was floated in August 2000 at $3.15 a share, raising $295 million. Seven years later, when Billabong’s shares touched $18.51, the company was worth $4 billion. But problems with expansion and mounting losses saw Billabong hit the skids. In June 2013, the shares hit a record low of 13 cents. In other words, in May 2007, a buyer was willing to pay $18.51 for Billabong; but in June 2013, a seller was willing to accept 13 cents. Let’s hope it was not the same person, because that 99.3 per cent potential loss is about as bad as it gets on the sharemarket.

Billabong was a growth story in the 2000s, and the sharemarket loved the notion of the Australian brand going global. But it eventually left the sharemarket after being taken over in April 2018, at the equivalent of 21 cents a share, by US sports and lifestyle company Boardriders.

However, as Stanford Brown’s research discovered, traffic toward the corporate knackery is constant. The trick to successful investing on the sharemarket is to have more of the stocks in their portfolios heading in the CSL or CBA kind of direction, rather than the Slater and Gordon or Billabong one.

Working Out Why Share Prices Change

From the moment the ASX opens for business at 10.00 am, until the trading day closes at 4.12 pm, shares in most of the 2,200 listed stocks are being priced continuously, upwards or downwards. Some stocks remain dormant, waiting to be traded.

A company’s value on the sharemarket reflects the perception of its earnings (profit) flow. Theoretically, if the sharemarket detects something about a company that may harm its earnings flow, the company’s share price falls. If the sharemarket hears good news about the company’s earnings, its share price rises.

The Australian sharemarket, like all sharemarkets, is greatly influenced by the US sharemarket. If the major US indices — the S&P 500 index, the Dow Jones or the Nasdaq Composite index — fall substantially, Australian share prices are likely to be under pressure for no other reason than US prices fell. Not fair, maybe, but it happens, and should be factored in to any short-term assessment of the local market. Since 2016, investors have had to add in another unpredictable influence — President Trump’s penchant for Tweeting his thoughts. These Tweets can cause market conniptions. Often this happens while Australian investors are asleep, and they can wake to find the US markets, or their futures versions, are down.

Influences on the price of a share

Share prices change because sellers and buyers are constantly reviewing companies’ earnings prospects. Over the long term, two factors determine the direction of share prices — future expectations of earnings and the price-to-earnings (P/E) multiples (see the sections ‘Earnings, earnings, earnings’ and ‘The pull of the P/E’, later in this chapter). Both of these factors depend on an evaluation from buyers and sellers as they learn more about the listed companies.

An increase in demand for a company’s shares means an increase in price, unless supply increases to match it. If an increase in demand is accompanied by a decrease in supply, the rate of the price rise increases. To coax sellers into parting with their shares, buyers raise their bid prices.

From the sellers’ position, if their shares can’t find buyers, the asking price drops until the shares sell. The keener sellers are to sell, the lower the price at which they offer their shares.

Sometimes a kind of equilibrium happens when buyers are happy to pay and sellers to accept at the prevailing price. Investors who chart prices call this a trading range or sideways trading.

Pricing and liquidity

Liquidity — the ease of buying or selling a share — can be a major influence on a share price. If a company’s shares are rarely traded, even just one active buyer or seller can decisively influence the share price in the short term.

If a share is not liquid, sudden trading can deplete the possible sellers without satisfying demand. Now, the buyers have to tempt other sellers by bidding up the stock and paying more for it than they intended. Similarly, a large selling order can overwhelm the possible buyers in the market. Now, the share price will go down to attract buyers. Non-liquid stocks are usually more volatile in price than liquid shares.

While supply and demand affect share prices in the market, it’s just as important to ask what influences supply and demand (see the sidebar ‘Buying back the farm’).

Earnings, earnings, earnings

The three most important words when you’re dealing with the sharemarket are earnings, earnings and earnings. Over the long term — which you should be thinking about when investing in shares — rising share prices follow rising earnings.

Over the long term, just over half of the total return of the Australian sharemarket comes from dividends (52 per cent, according to AMP Capital). The rest comes from the increase in the value of companies, which rises as the retained earnings compound inside the company. Given good management, the earnings — and thus the dividend — grow over time.

Table 3-1 shows a simplified version of how a company — and thus its shares — grows in value. In the example shown, a business is started with $100 in assets. The business makes a profit of $10 in its first year, a return of 10 per cent. Of that profit, the business decides to pay half out as a dividend to shareholders, and retain the other half for reinvestment. Table 3-1 shows what happens to business assets if these returns and pay-out rates continue for six years.

TABLE 3-1 The Earnings Matrix

Year |

Business Assets ($) |

Profit (Return on Equity) ($) |

Dividend ($) |

Retained Earnings ($) |

1 |

100.00 |

10.00 |

5.00 |

5.00 |

2 |

105.00 |

10.50 |

5.25 |

5.25 |

3 |

110.25 |

11.00 |

5.50 |

5.50 |

4 |

115.75 |

11.60 |

5.80 |

5.80 |

5 |

121.25 |

12.20 |

6.10 |

6.10 |

6 |

127.65 |

12.80 |

6.40 |

6.40 |

7 |

134.05 |

Source: Investors Mutual Limited

As Table 3-1 shows, in its second year, the company also makes a return of 10 per cent. But this figure now applies to a larger asset base, by virtue of the $5 of retained earnings from year one. The dividend payout ratio remains at half of the profit, so it increases — as does the amount of retained earnings. In this example, the return is a consistent 10 per cent; because this applies to an ever-increasing asset base, if the payout ratio remains the same, the dividend and the amount of retained earnings increase every year.

If dividends are a poorly understood feature of sharemarket investment, retained earnings are even less visible. But as retained earnings compound over time, the part they play in building wealth is very important.

Successful companies grow their revenue and profits. When CSL was privatised by the Australian government in 1994, it had revenue of $193 million and profit of less than $20 million. In the 2019 financial year, the company (which these days reports its results in US dollars) earned revenue of US$8.5 billion (A$12.1 billion) and a profit of US$1.9 billion (A$2.7 billion.)

The pull of the P/E

The price/earnings (P/E) ratio simply relates a share’s price to its earnings. However, it is also a strong driver of a company’s share price because it reflects the going rate for the company’s earnings, in that the market pays a premium for companies with earnings that are growing faster.

The stronger the earnings growth, the higher the prospective P/E is pushed — this is P/E expansion. P/E expansion is one of the three components of return from the stock market, along with earnings growth and dividend yield. When it works well, P/E expansion is a turbo-charger for share prices. When it reverses — and becomes P/E contraction — it can wipe out several years of capital growth.

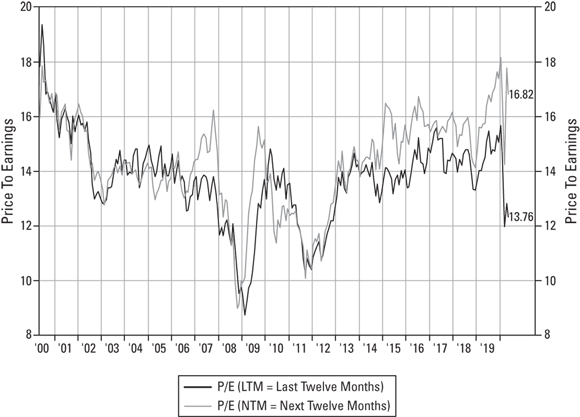

Source: FactSet

FIGURE 3-3: S&P/ASX 200 P/E changes, historical and forward, 2000–2020.

I provide more detail on the P/E ratio in Chapters 5 and 7, including how to use it when assessing what is a ‘value’ stock and what is a ‘growth’ stock.

The tyranny of expectations

Because company earnings are a major factor in determining share prices, any change in the direction of earnings or earnings forecasts causes a market reaction. This reaction immediately affects the supply and demand for a share. For example, a surprise in reported profit, or an upgrade or downgrade to a profit forecast, generally results in a reaction from buyers and sellers. The rule here is that the market hates to be surprised with bad news. However, the market likes a surprise of good news, especially a rise in profits and earnings.

The companies’ investor relations departments, and their management, work with analysts to keep them as informed as possible — without breaching commercial confidence, of course, or giving them priority over the market.

Watch out for announcements

The continuous disclosure regime required by the ASX means that a constant stream of announcements is released by the 2,200 listed companies, all day, every trading day, Many of the announcements are mundane corporate house-keeping, but occasionally a genuine bombshell is sent out, flagged by the ASX with a red ‘$’ symbol — denoting ‘price-sensitive,’ which means ‘must read, could affect the share price’. If the announcement is virtually certain to affect the share price, the stock will usually be placed in a trading halt before the announcement and stay temporarily suspended to allow the market to digest the new information.

An example of good news came in October 2019 for shareholders of biotech company Actinogen Medical, which announced excellent results for its drug candidate Xanamem in a trial against Alzheimer’s disease. The Phase 1 clinical trial (for more information on clinical trials, see Chapter 8) demonstrated a ‘significant improvement in cognition’ in the trial volunteers — and Actinogen shares surged by 467 per cent.

Anti-microbial specialist biotech Zoono was trading at 47 cents in January 2020 before COVID-19 truly emerged. On the back of its Microbe Shield, a patented polymer that forms a barrier layer on all surfaces — human, building or machine — when applied as a spray, foam or wipe, the stock motored quickly to $1.94.

The same kind of thing is a feature of the resources stocks, and a share surge on the back of a promising drilling result, or a new discovery, has been one of the great traditions of the Australian sharemarket since its earliest days. In particular, the names of nickel explorers Poseidon and Tasminex live on as synonyms for instant riches — and the inevitable bust. On one day in January 1970, Tasminex shares surged from $3 to $96 on the basis of a false report that the company had struck nickel at Mount Venn in Western Australia. Fellow nickel explorer Poseidon made that jump look paltry, rocketing from 50 cents to $280 in a few months, on news that it had struck nickel nearby at Windarra.

In more recent time, in July 2012, nickel explorer Sirius Resources was trading at 5 cents until news of two huge nickel discoveries, first Nova and then Bollinger, in Western Australia’s Fraser Range area, sent the stock soaring to $5 by March 2013 — a 100-bagger. The second discovery sent Sirius rocketing from $2 to $5 in only a few days. Sirius was taken over by Independence Group (now IGO Limited) in 2015.

The most eye-watering take-off in stock price in recent years was that of Stemcell United, which extracts plant stem cells for use in traditional Chinese medicine. Stemcell shares pushed the ignition button in May 2017 on the back of (very vague) plans it announced to ‘pursue opportunities in the medical cannabis sector,’ then one of the hottest sectors on the Australian sharemarket. Stemcell stock bolted from 1.3 cents to 40 cents, for a gain of almost 3,000 per cent. The sad sequel is that Stemcell has returned to 1.3 cents.

Price movements are usually more staid in the industrial sector of the market, although good news is still good news, and double-figure gains in share price are often seen in this sector. On any given day, somewhere on the market, you can be sure something is soaring skyward — however temporarily.

Profits, expectations and ‘confession season’

Companies report their financial results to the stock exchange at least twice a year — an interim (half-yearly) and a preliminary final result. During the reporting seasons, January–February and July–August, the market is inundated with profit announcements. The two main reporting dates are 31 December and 30 June. Most Australian companies use the 30 June ending date for the financial year, but some follow the American model and use the calendar year as the financial year. Companies with a financial year that ends on 30 June report their final results for the year in July–August. At this time, companies that use the calendar year as their financial year report their interim (half-yearly) result to 30 June. The reverse occurs in January–February.

For most of the year, expectation of profit is what influences the share price. However, on the two trading days when the interim and preliminary reports are released, a company’s actual profit results affect the share price.

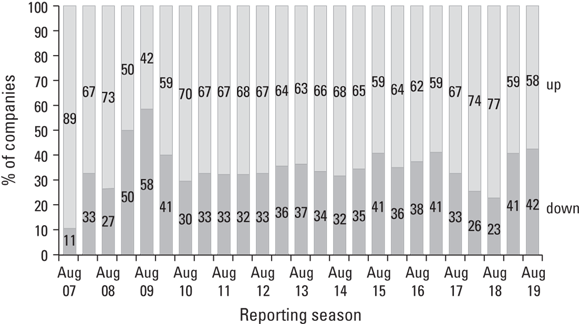

The weaker profits inevitably flowed through to dividends. AMP Capital reported that only 49 per cent of companies increased their dividends in 2018–19, well below the longer-term norm of 62 per cent. And 28 per cent of companies actually cut their dividends, which was the most in the last seven years.

During periods when a large proportion of listed stocks (really only the S&P/ASX 200 stocks are covered in this analysis) are beating their profit estimates, that is the main driver of P/E expansion, because the sharemarket is happy to pay higher P/Es for stocks with a good record of beating profit expectations.

Source: AMP Capital

FIGURE 3-4: 2007-2019 ASX reporting seasons, Australian company profits relative to a year ago.

When guidance alerts the market that the company is poised to announce a big profit increase — called a profit upgrade — the reaction is equally quick, with a price rise in the shares. But with the opposite, a profit warning, the reaction is equally quick — and savage. Share price falls of up to 40 per cent are common when highly favoured companies shock the market with a profit warning. This movement is P/E contraction in a very short period of time, and unfortunately — if you’re holding the shares — the ‘P’ (profit) contracts with the P/E.

In early 2020, as the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic spread, the ASX told its listed companies that they did not have to provide forward-looking statements, and could — in light of how the economic situation had changed so drastically, so quickly — ‘withdraw’ previously lodged guidance. A flurry of retracted guidance statements ensued, and any company maintaining its existing guidance was treated as if it had upgraded its expectations.

The reaction of the market to a profit downgrade can be horrendous — especially if it happens more than once. From levels approaching $9 in 2018, horticulture operator Costa Group has had its value cut by almost two-thirds, as it downgraded its profit guidance four times in a little over a year due to a series of issues, including drought, in its Australian and Moroccan growing areas. The market has brought the stock price down from a clearly too-optimistic level.

Treasury Wine Estates dismayed the share market with a surprise profit downgrade in January 2020, mainly on the back of problems in its commercial wine business in the US, where it was hit by a glut of cheap wine. Over two days alone, its share price took a 30 per cent dive, stripping $3.9 billion from its market capitalisation.

Boosting power of takeover bids

Any company listed on the sharemarket is up for sale. Another company or group of investors can make an offer to its shareholders at any time. A takeover bid is the kind of news that has little to do with earnings but can quickly affect a share price. Takeover activity can happen anywhere on the market at any time — from the depths of the resources exploration tiddlers to the very heights of the market, as with BHP’s unsuccessful $165 billion bid for rival Rio Tinto in 2008.

Usually, the shareholders of a company undergoing a takeover bid are happy with the instant boost this gives the share price. If the bidding company offers a substantial premium to the market price, shareholders may be coaxed into selling their shares. When another company gets involved, the takeover becomes a bidding war. This situation can bring an increase in share price worth several years of capital growth — or which reinstates some of the market value lost in market slumps such as the GFC and the COVID-19 crash.

A company considered a takeover target is said to have corporate appeal. When rumours of a takeover occur, speculators buy the company’s shares hoping to turn a quick profit when a bid is announced. The kind of bids speculators are looking for include:

- A bid that doesn’t prise open the target company’s share register, meaning the predator company has to lift its offer

- A bid that flushes out another potential predator and the two of them (or even more!) slug it out

A takeover bid can be an instant spark for the target company’s share price. In September 2019, milk and infant formula producer Bellamy’s Australia soared 55 per cent to $12.89 after receiving a $1.5 billion takeover offer from China Mengniu Dairy Company. Remote-site energy provider Zenith Energy jumped 45 per cent on receiving a takeover bid from private equity group Pacific Equity Partners in March 2020. And junior resources company Capricorn Metals rocketed more than 59 per cent after gold miner Regis Resources lobbed a takeover bid (which was ultimately unsuccessful) in September 2018.

The first bid can only be the start of proceedings. What investors most want to see is a bidding war in which their company is sought by more than one party (see the sidebar ‘Warrnambool Cheese & Butter takeover tussle’). Of course, takeover action can go the other way. In December 2019, business lending group Scottish Pacific announced a bid for trade finance and payroll manager CML Group, at 57 cents a share. CML Group shares jumped 19 per cent, to 56 cents, and a scheme of arrangement was subsequently announced. But in May 2020, the scheme was terminated by mutual agreement. On that news, CML Group shares sank 42 per cent, to 28 cents, taking them back to where they had been trading three years earlier. That’s a big ‘ouch’ for shareholders.

These numbers reflect the performance of the sharemarket index — not that of individual companies. Over the years, some companies perform much better than the index; however, an awful lot don’t.

These numbers reflect the performance of the sharemarket index — not that of individual companies. Over the years, some companies perform much better than the index; however, an awful lot don’t. Although diversification is a fundamental law of investment, the concept of diversification can easily be misunderstood. Spreading invested funds across a number of different assets reduces the overall risk for your portfolio because you’re not relying on only one asset as your investment.

Although diversification is a fundamental law of investment, the concept of diversification can easily be misunderstood. Spreading invested funds across a number of different assets reduces the overall risk for your portfolio because you’re not relying on only one asset as your investment. The process of setting a company’s value on the sharemarket is subject to the reality that the sharemarket is, on a day-to-day basis, hugely influenced by the prevailing collective nvestor sentiment regarding the health of the global economy, and geo-political happenings. Anything that is perceived to be negative for economic growth, or world trade, or for a companies’ ability to conduct their business profitably can potentially affect that sentiment — in both directions — and cause a widespread general rise or fall in share prices. Investors are always looking at the market information, including economic news (particularly changes to interest rates) and political events, which can cause share prices to rise or fall.

The process of setting a company’s value on the sharemarket is subject to the reality that the sharemarket is, on a day-to-day basis, hugely influenced by the prevailing collective nvestor sentiment regarding the health of the global economy, and geo-political happenings. Anything that is perceived to be negative for economic growth, or world trade, or for a companies’ ability to conduct their business profitably can potentially affect that sentiment — in both directions — and cause a widespread general rise or fall in share prices. Investors are always looking at the market information, including economic news (particularly changes to interest rates) and political events, which can cause share prices to rise or fall. The P/E can be historical, where the ‘E’ refers to the most recently reported earnings, or forward-looking or ‘prospective’, where the ‘E’ figure is the consensus of analysts’ expectations. According to financial data firm FactSet, over the last 20 years the Australian sharemarket has traded at an average historical P/E of 15.6 times earnings and an average forward P/E of 14.3 times earnings (for a chart of the fluctuations around these averages, see

The P/E can be historical, where the ‘E’ refers to the most recently reported earnings, or forward-looking or ‘prospective’, where the ‘E’ figure is the consensus of analysts’ expectations. According to financial data firm FactSet, over the last 20 years the Australian sharemarket has traded at an average historical P/E of 15.6 times earnings and an average forward P/E of 14.3 times earnings (for a chart of the fluctuations around these averages, see