CULTURAL CONTESTATION

‘Orientalizing’ in the archaic and classical periods

From even before the early Iron Age, the peoples of the Greek mainland had shown an interest in the cultures and civilization of Asia. in the wake of the Mycenaean collapse, this interest was reinvigorated, and images from Asia became an important and continuous source for the development of Greek ideas, culture and political theorizing (this last was particularly the case at Athens).

We have already seen in an earlier chapter how the Greeks (and especially the Greeks of Asia Minor) in the archaic period found in exotic and barbarian Asia an important ‘edge’ against which they could define and assert a self-conscious Greek identity. Furthermore, we also saw that this negotiation of difference was not necessarily simple. The very act of negotiating cultural boundaries could also entail recognizing similarities, or even assimilating elements from other cultures in order to create new (and different) cultural expressions. Although some have seen this Greek use of oriental images as not much more than simple imitation, in fact by adapting cultural forms from Asia the Greeks developed an independent cultural idiom which reflected particularly Greek ideas and values. What oriental images and ideas provided was a starting point for working through and expressing something particularly Greek, and an idiom for exploring both cultural forms and political institutions.

In this chapter we will begin by looking at the complex ways in which the Greeks developed oriental motifs in both the archaic and classical periods. We will then turn more specifically to the Panhellenic war against the barbarian and especially the fear of the Persian/barbarian that was integral to it, particularly at Athens. We will consider how these ideas of the barbarian war and the fear it engendered were used in conjunction with other Panhellenic themes, both in positive and negative ways, not only to express Athenian relations with the rest of the Greek world, but also to conceptualize the Athenian democratic state.

Contested barbarians

Commentators often point to Aeschylus’ Persians, produced in 472 Bc, as the prime example of the Asian barbarian as anti-Greek in the post-war period. Edith Hall, in particular, has shown the way in which the polarity of Greek and barbarian appears in the play in its developed form.1 The Persians are represented as different and exotic through their vocabulary, behaviour, hierarchies, decadence and unrestrained emotion.2 In addition, for Aeschylus Persia was synonymous with wealth (e.g. 250, 842; cf. [Simonides] XXI Page FGE), and the poet uses the evocative and sensual image of the ‘luxurious’ marriage-beds that the young men of Asia have left behind (537–45; cf. 134–7, 288–9) to emphasize Asian decadence. This cultural polarity between Greek and barbarian is established in Atossa’s dream in geographical terms at the beginning of the play when she sees two women: one wears Persian robes, the other Doric; one lives in Hellas, and the other in the barbarian land; one bears proudly the yoke of servitude placed on her by Xerxes, the other shakes it off (181–97). The geographical and cultural opposition then provides the political paradigm for the play: Greek order is contrasted with Persian disorder (375–428), and rule by one man is contrasted with rule by none (241–2).

However, the Persian Wars is not as significant a point of change in the representation and interpretation of the non-Greek in the periods as has sometimes been suggested. We have already seen in an earlier chapter that the idiom of ‘barbarism’ employed by Aeschylus was familiar from the archaic period: Xerxes’ cruelty, violence, and disregard for the gods (369–71, 809–15, 1038–65) resonate with the cruelty and lack of respect for the gods of the Cyclops, Polyphemus, and with the violence of the Laestrygonians. Drawing on the ‘repertoire of otherness’ that had developed during the archaic period, Aeschylus ‘orientalizes’ Persia in the same ways as Lydia had been orientalized in the sixth century (indeed Aeschylus refers to the luxurious lifestyle of the Lydians: άβροδίαι/ποι Λυδοί: 41). Not only were the Greeks already interested in the non-Greek as a cultural opposite before the Persians, but also there had long been a subtle and relatively developed interest in non-Greeks and non-Greek culture,3 which worked in more than one direction. As well as the focus for definition of Greekness through difference, the Greeks also adapted Asian cultural forms as a positive means of self-expression. This orientalizing in the archaic period is well documented, and is often described as a form of cultural borrowing, while the Greeks’ own innovation is downplayed. In the next section we will look at the ways in which the Greeks worked with oriental ideas, not to supplant or to replace their own originality, but as a vehicle for creating it.

Oriental ‘borrowings’

The Hellenes had long been in contact with Asia. Even before the settlements in the Levant in the eighth century, luxury items were being brought to Lefkandi on the island of Euboea, and excavation of the tombs at Lefkandi (which date to the mid-tenth century) has produced artefacts showing clear links with the civilizations of Asia:4 a Syro-Palestinian juglet found at Lefkandi dates to the late-eleventh century;5 from the tenth century, Phoeni cian faience and glass, Egyptian faience, and egyptianizing bronze situlae and bronze bowls (probably Phoenician) have been found, as well as Cypriote jugs, a centaur, and a mace-head of Cypriote type; from the ninth century, a quantity of gold jewellery either from Asia or with oriental inspiration, and Phoenician stone and faience seals.6 Other Greeks were also receiving goods from Asia in the tenth and ninth centuries, especially Athens and Crete.7

Also in the ninth century, Phoenician craftsmen who based themselves in Lefkandi, Athens, Crete and the Dodecanese (and possibly other parts of Greece including Laconia, Thera and Thasos) were involved in the receipt and production (by Phoenicians) of these items.8 In fact, although there is no certain evidence for Phoenician involvement in the West before the ninth century, it seems likely that Greeks, especially Euboeans, were not only using trade networks established by the Phoenicians, but also working with Phoenicians, especially on Sardinia and Cyprus.9 In addition, Phoenicians lived side-by-side with Greeks at Pithecussae in the eighth century.10 Even more importantly for our purposes, however, Boardman has shown by the distribution patterns of North Syrian objects (ivories, metalwork, and Lyre Player seals) that the Phoenicians were not the only traders involved in the carriage of goods from Asia, but that the Greeks (mainly Euboeans, although others such as the east Greeks had a role later on) played a significant part in distribution to Greek lands probably the most significant part –from at least the tenth century.11 With the establishment of Greek settlements on the Levantine coast in the eighth century the trickle of oriental artefacts and images which found its way to mainland Greece became more of a torrent.12

In the Iron Age and archaic period, the nascent Hellenes, as their horizons expanded and they began to travel more widely in the Mediterranean, gradually came to be more aware of those who were not Hellenes, that is, those who did not subscribe to the same set of cultural, moral and ethical values. However, having come into contact with the peoples of Asia, far from whole-heartedly rejecting their ideas as alien, at least by the seventh century some Greeks embraced them. Indeed, in recent years it has become fashionable to show the degree to which Greek literary and visual arts were dependent on the Asian cultures and civilizations,13 and it has sometimes been said that Greek culture was simply an adjunct of Asia. West, for example, says: ‘As it was, the great civilizations lay in the East, and from the first, Greece’s face was turned towards the Sun. Greece is part of Asia; Greek literature is Near Eastern literature.’14 More recently, Sarah Morris in more moderate terms also claims a Near Eastern heritage for Greek culture, and argues that the ‘orientalizing’ period, which she claims extended from the Bronze Age to late antiquity, ‘remains better understood as a dimension of Greek culture rather than a phase’.15

Gods and heroes

Without doubt, Greek heroic literature found its template in the literary traditions of the cultures of Asia. As an example of fairly clear borrowings, there are obvious parallels between Hesiod’s Theogony and the Hittite Song of [Kumarbi], and West has shown how there are also correspondences, though to a lesser extent, with other myths from Asia, such as the Babylonian Enumaeliš.16 Consideration of just the Song of [Kumarbi], however, makes the point, and shows the extent to which the Theogony uses the much older tradition to structure its divine genealogy. In the Kumarbi, for example, the succession of Anu (‘Sky’), Kumarbi (corn god), and Tessub (Storm-god) have counterparts in the Theogony s Ouranus, Cronus (who may derive from a harvest god), and Zeus (a storm god). Further, both Anu and Ouranus have their genitals cut off, and the dismembered genitals produce new gods. Anu warns Kumarbi and Ouranus warns the Titans that they will have their revenge for the castra tion. Both Kumarbi and Cronus have gods in their belly. Both Kumarbi and Cronus are given a stone to eat in place of a child, and in both cases the stone later becomes an object of cult. Teššub/Zeus attacks Kumarbi/Cronus and their allies. A deity may have been born from Kumarbi’s head, just as Athena was from Zeus’.

The resemblances between the two texts are so close as to presuppose in the creation of the Theogony more than just a general familiarity with the older story, but a quite detailed knowledge. Nevertheless, there are also substantial points of difference. For example the purpose of the Theogony is not just to tell the story of Zeus’ divine kingship, but also to provide a framework for synthesizing, rationalizing and explaining the Greek pantheon; even West concedes that the content of the poem is ‘Greek, or at least hellenized’ (so that, he argues, it must date back to the Mycenaean period).17 The primary social function of the two poems also differed: while the Hittite poem was used for and embedded in ritual, the Greek poem had no such significance.18 It borrows heavily from Asian forms, but is still a Greek poem.

Other myths and stories also found their way to the Aegean and influenced or inspired Greek versions. For example, the Akkadian Atrahasis, which told the story of the hero Atrahasis and the great flood (and which was also used in the Epic of Gilgamesh and retold in the Old Testament with Noah as protagonist), was adapted by the Greeks, although probably not until the mid-sixth century (it is first alluded to by Epicharmus and Pindar in the first half of the fifth century).19 Burkert also argues that the Atrahasis influenced passages in the Iliad.20

Parallels can also be drawn between the Epic of Gilgamesh (best known in its Akkadian version), and the Iliad and Odyssey. Some of West’s strongest claims for Asian influence concern the impact of the Gilgamesh tradition on Greek epic; he argues that there must have been ‘some sort of “hot line” from Assyrian court literature of the first quarter of the seventh century’.21 In fact, Gilgamesh can be compared to both Achilles and Odysseus. Like Achilles Gilgamesh has a divine mother, and like Achilles he also has a close and formative relationship (with Enkidu). Enkidu is chosen by the gods to die, and as a consequence Gilgamesh is both distressed at his friend’s death and forced to come to terms with his own mortality. Likewise, Odysseus and Gilgamesh are men who have travelled widely and experienced much. Odysseus’ adventures with Calypso and Circe recall Gilgamesh’s encounter with the goddess Ishtar, who wants to marry Gilgamesh, though he rejects her. Odysseus’ journey to Hades also echoes Enkidu’s description of the underworld on Tablet XII, an Akkadian translation of a Sumerian poem found at Nineveh.

Yet, while Odysseus and Achilles may be modelled on Gilgamesh in some respects, they are both – and Achilles in particular –different kinds of heroes.22 Gilgamesh confronts his mortality in the death of his Enkidu, and seeks everlasting life, although ultimately he has to resign himself to his own human weaknesses and the fact that he too will die. Achilles’ response to his mortality works in a contrasting direction. Although a ‘swift death’ is predicted for him if he fights the Trojans (e.g. Il. 1.352, 415–16, 505–6, 9.410–16) and Thetis prophesies that Hector’s death will bring on Achilles’ own (Il. 18.95–6), his response to the death of Patroclus is to seek to avenge his friend by killing Hector (‘Since neither my heart urges me to live nor to remain among men unless Hector is first struck with my spear and loses his life, repaying the penalty for the slaughter of Patroclus the son of Menoetius’: Il. 18.90–4). Further, with his friend’s death, Achilles even welcomes death himself. ‘May I die at once,’ he says, ‘since I was not destined to bring help to my companion as he was slain’ (Il. 18.98–9). Rather than trying to escape his doom, Achilles becomes philosophical about the fate of man and his relationship to the divine. He says:

I will accept my fate at that time when

Zeus wishes to accomplish it and the other immortal gods;

for not even the might of Heracles escaped death,

who was very dear to Zeus, the son of Cronus, the king;

but destiny overcame him, and the grievous wrath of Hera.

(Il. 18.115–19)

Further, that Achilles knows from the moment of Patroclus’ death that he too will die is his tragedy, but it is also the pivotal moment in his heroic development. In the knowledge of his death, he changes from a young man, caught up in the mortal concerns of lack of honour and lost prizes, to a mature hero who can accept the responsibilities of life and death, and the remaining action of the poem is coloured by this knowledge.23 The maturity he has found in his grief allows Achilles the insight to see that the father of Hector, his enemy, was just like his own father, and that Priam’s grief was not so very different from his (Il. 24.507–512), and for that reason deserves pity.

The stories of Gilgamesh and Achilles may have narrative and thematic similarities, but the way in which the poets choose to treat the theme of the heroes’ confrontation with death is profoundly different.24 Gilgamesh grieves that he cannot escape death. His heroic development culminates in his resignation and acceptance of the inevitability of his doom. For Achilles, on the other hand, acceptance of death brings understanding of the relationship between gods and men, as well as self-knowledge, maturity, and true virtue. Greek literature may have found a fund of material to work with in Asian literature, but the stories that were created from it reflected Greek interests and concerns. Gilgamesh reflects on the inescapable fate of mankind. Achilles shows how man can be greater than (and for) it.

Domesticated monsters

Greek art was also influenced by the cultures of Asia, but in a different way for similar ends. The impact on Greek art of the seventh century is most obvious in the so-called ‘orientalizing revolution’, an artistic movement which provided a fresh idiom for exploration of new ideas. In the eighth century, as we have already seen, the Euboeans were in contact with the civilizations of Asia (possibly through Al Mina), and large amounts of Euboean pottery found their way to the Levant and Near East.25 Although artistic expression in many parts of Greece remained conservative, exotica presented as dedications have also been found at the Samian Heraeon and Perachora (two sanctuaries which, along with Eretria, were also among the first to build temples in the eighth century, suggesting close links with Asia).26

Also in the eighth century, in vase-painting, there were some oriental borrowings in the depiction of animals such as deer and gazelles, although in shape and arrangement these were subordinated to the geometric theme.27 In other media, gold bands from the last quarter of the eighth century bear animals which are oriental in technique and inspiration, though still arranged in a rhythmic geometricizing sequence.28 On Crete, which resisted Attic-style geometric pottery until the end of the ninth century, a bronze tambourine from the Idaean cave, dating to the eighth century, stands out as a work ‘surely by an eastern hand’, as do embossed shields also from the Idaean cave and elsewhere in Crete, as well as Delphi, Dodona and Miletus.29

At the end of the eighth century, after more than a century of quite profound contact with Asia and Asian cultures, oriental motifs truly seized the artistic imagination. After the geometric pottery style had run its course, first at Athens jewellery displayed sphinxes and mythical creatures, then, with new shapes and new techniques, painted pottery appeared at Corinth at the end of the eighth century, followed by Athens, the Cyclades and Crete from about 700 Bc.30 In this new style, which replaced the now exhausted Late Geometric, exotic animals and plants abounded. In sculpture, mould-made clay plaques of the naked Syrian goddess Astarte were translated into clothed figures of Aphrodite with what became known as the ‘Daedalic’ style: frontal relief, angular form, wig-like hair, large eyes and prominent nose.31 These Daedalic figures were then produced on jewellery, vases and wheel-made figurines, and finally carved in stone, though the idea for monumental sculpture probably derived from Egypt.32

Initially, Greek craftsmen copied oriental forms. Coldstream, for example, identifies ninth-century granulated earrings from Lefkandi as crude copies of originals from Asia.33 Once new techniques had been mastered, however, the Greeks set out to create something of their own. With painted pottery, the Corinthians who originated the style applied the new motifs, both flora and fauna, to a medium in which it had been virtually unknown in this period among the cultures of Asia.34 Boardman also points to ivories from Athens dating to the middle of the eighth century. Modelled on plump Astarte figures from Syria, although ‘their pose and caps are derived directly from the ivory figures of the naked goddess Astarte which are so common in the Near East’, ‘their slim bodies, angular features and the meander on their flat caps proclaim their Greekness’.35 Osborne, comparing a bronze statuette of the Egyptian goddess Mut with a mid-seventh-century wooden statuette of Hera, both from the Samian Heraeon, discusses the way in which the Greek artists treated the human body differently, and, by placing emphasis on the head rather than body-shape, used oriental motifs ‘to think with’ in order to explore and give expression not just to shape, form and the fantastic, but to the relationship between gods and men.36

A similar transformation occurs in monumental sculpture. Based on Egyptian prototypes, the naked male figures are different in purpose and spirit from the Egyptian originals.37 While the Egyptian figures were clothed and supported, the Greek figures were naked and the rear support has been taken away. The Egyptian figures represented powerful individuals, the Greek kouros, the statue of the naked youth, on the other hand, was generic. As Osborne says, unlike the Egyptian figures who impress themselves on the viewer,

the viewer writes himself upon a kouros. The stone figure, from near or far depending on its scale, returns the viewer’s gaze without adding any mood or experience; indeed unlike the gaze returned by a mirror, this gaze does not duplicate the mood or experience of the viewer. The man who looks on a kouros finds himself being looked upon by a figure that is male and impassive: here is a male who stands firm, unbending, and constant. Such a figure makes a dutiful servant to the gods or to the city, but also an image of the unageing constancy of the gods themselves.38

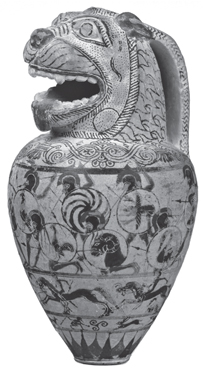

Even Asian monsters were domesticated. Griffins, known from the Bronze Age and then revived from the eighth century as decorative attachments to cauldrons and then figures on pots, were fierce but became taut and elegant creatures in Greek hands.39 High prestige items such as these were also joined by pots, including the tiny perfume pots, the aryballoi. Beautifully executed lions and panthers prowl over miniature perfume pots, and display a ‘power and prettiness’40 which was at once undermined and trivialized by the contents of the pots, while at the same time empowering the owners by their potent symbolism of access to a wider (and more socially privileged) world.

As an example of the Corinthian orientalizing style, the tiny Macmillan aryballos , a perfume pot from the mid-seventh century, surprises and delights (Fig. 2). The lion-shaped mouth of the pot roars (or laughs), hoplite figures battle fiercely around the central band, while dogs chase rabbits beneath, presenting an ideologically complicated mix of images. The decoration is exuberant and energetic, and the miniaturist detail betokens a society that could afford to expend detail on something so small and frivolous, and to revel in it.

Fig. 2. 'Macmillan' aryballos, Protocorinthian; decorated with eighteen warriors, a hare-hunt and horse-race (British Museum, 1889, 0418.1; photograph © The Trustees of the British Museum).

This tiny aryballos was truly a product of its times. The seventh and sixth centuries were two of the most turbulent in Greek history, although not because of the threat of the wider world, which bythe seventh century had, at least for the Greeks of the mainland, become safer and better known. By the mid-seventh century, the Greeks were familiar with travel to Asia and the western Mediterranean. A permanent post had been established in Egypt, and the north-African coast had been settled, as had parts of Sicily and Italy. Their pottery travelled with them. Generally found in locations associated with death and the divine (sanctuaries, cemeteries in Italy and Sicily), Corinthian pottery also travelled, though not always or necessarily through trade.41

However, the eighth and seventh centuries were a time of social upheaval. Michael Shanks highlights the importance of travel and warfare for allowing a new social mobility, as they provided opportunities for ‘enrichment of lifestyle, for acquiring the expensive equipment of a hoplite, for acquiring the trappings of a landed aristocracy in the absence of their inheritance’.42 These were important and exciting times as communities started to find a new shape and social order, an excitement exemplified by the juxtaposition of hoplites with elite hunting scenes and Asian lions on the Macmillan aryballos.43 There were new ideas and new ways of thinking, not just about the world outside, but the world inside as well, since the changes and upheavals of the early archaic period certainly produced social tensions within communities.

In fact, Osborne, Morris and Shanks interpret the seventh-century ‘orientalizing revolution’ in social terms. For Morris, the adoption of oriental motifs was aristocratic, and represented a means of justifying elite values.44 ‘True aristocrats,’ he says, ‘were comfortable using the East, moving within their own version of the culture of Gyges.’ For Morris, perfume pots belonged to the world of the symposium:

The new symbols justified their users’ claims to superiority – they virtually mixed with the gods themselves, just like the ancient heroes, on whom society had depended for its very existence; and they felt like the kings of the East, whose power vastly exceeded that of the Greeks.

For Shanks, on the other hand, Corinthian pottery promotes an aristocratic ideology, but

...is one of the several material forms which provide a medium for the transient present to be subsumed beneath larger and transcendent experiences. These are to do with the personal, death, the divine, animal and bodily form, an expressive aesthetics, the exotic and ‘other worldly’, and masculine sovereignty ... For the artifact enfolds the interests and interpretative decisions of those who made it, and these may be ideological, bolstering inequality, reconciling social contradictions, working on social reality to make it more palatable.45

Similarly, Osborne links the proliferation of orientalia in the seventh century with the opening up of society, and the aspirations of a non-elite class.46 For him, the little perfume pots represent the popularization and increased accessibility of oriental imagery which had formerly been the preserve of the elite.

Indeed, in archaic society political tensions were generated by more than one source. There is evidence in archaic Greece of pressure between status groups. For example, Theognis of Megara bitterly complains:

Cyrnus, this polis is still the polis, but there are other people,

who previously knew neither justice nor customs,

but who used to wear goat skins on their sides,

and lived like deer outside this city.

And now they are agathoi (‘good men’), Polypaïdes, and those who before

were esthloi (‘noble’)

are now deiloi (‘wretched’). Who could endure looking on these things ?

And they deceive each other and mock each other,

not able to distinguish the principles of the kakoi (‘wicked’) or the agathoi.

(Theognidea 53–60 West IE )47

Likewise at Athens, Solon was clearly dealing with a situation where there were some who had traditionally been excluded from political power, but who now had wealth and wanted power as well (e.g. frs. 5, 13, 34 West IE 2 ). Across the Greek world, there also seem to have been economic tensions, and demands for a redistribution of wealth through a redistribution of land (Arist. Pol. 1306b39–1307a2; Solon fr. 34 West IE 2 ). Nevertheless, as we have already seen in chapter 2, Greek society tended to be aspirational. Solon in his poetry may have insisted that he gave neither the dēmos too much nor gave too little to ‘those who had power and were admired for their possessions’ (οί δ’ είχον δύναμ/ν και χρήμασι/ν ησαν άγητοί), (frs. 5, 34 West IE 2 ), but his reforms failed to bring political stability to Athens (Ath. Pol. 13.1–3). Further, taken together with Theognis’ resistance to a new social order, Solon’s insistence that he will not change social structures through his political and economic reforms seems to indicate not only a social conservatism by the elite, but also resistance to the changing shape of society as the traditional elite were placed under pressure by those who aspired to social status as well as political power.48 The Macmillan aryballos with its elitist hunting scene below the community-based aspirations of the fighting hoplites, together with its sympotic and divine contexts,49 suggests a society where the audience for this perfume pot and others like it wished to blur an apparent conflict between communal polis and elite symposium.

Nevertheless, although the Greeks were happy to receive luxury items from Asia, in the visual arts there was initially an apparent reluctance to adopt oriental motifs in their own art.50 The sudden use of these images in Greek art in the seventh century possibly reflects a society that needed a new and safe idiom. The new needs of increased prosperity and the new ways of organizing society had to be accommodated. The story of the archaic period is just as much one of accommodation as of conflict. It is often observed that the orientalizing revolution in Greek art was superficial, but the superficiality was important. By the seventh century, oriental motifs seem to have tran scended class and provided for both the elite and those who wanted to be elite a safe idiom in which to think about danger, although not necessarily or always the dangers of the external world, as the Cyclopes seem to have done. In the visual arts of the seventh-century there seems little actual interest in the monsters as monsters. Rather they express controlled excitement, energy and the conflict of new visions as well as new horizons, although the dangers are domesticated and brought under control.

Centres and peripheries

And indeed the artistic idiom of Asia was exciting and different. As the Greek communities looked increasingly outwards in the early Iron Age, they attempted to locate themselves in the wider world. As travellers without maps, they needed to describe space and movement across space. By the same token, as they moved into the sphere of influence of Asia, the Greeks explored their relationships with oriental cultures. One reaction was to see themselves as living on the periphery of Asia, and consistently throughout the early Iron Age and archaic period, and even into the fifth century, orien talia were used as social markers by both the elite and those who aspired to join them. As we shall see in the next chapter, oriental genealogies were also developed, and even increased in significance, as the Greeks aligned themselves against the civilizations of Asia. Indeed, as relationships with the peoples of Asia became more intense, the need to place themselves within the boundaries of the Asian empires became more pronounced.

Nevertheless, as we will see in the sections that follow, increased contact with other cultures, and the cultures of Asia in particular, helped to define difference. Despite – and even because of – this difference, oriental images were, as Osborne puts it, also useful ‘to think with’. Poetic forms were adapted to express Greek concerns and values and man’s relationship with the gods and other men. While in the early Iron Age oriental items were used to mediate relationships both in society and with the gods (dedications of tripods, for example, made a statement both to mortals and the divine by declaring status through a heroic value system and the conspicuous consumption of wealth), from the mid-seventh century increased contact exacerbated the awareness of essential difference so that the cultures of Asia became a foil for Greek culture. Asia, however, was not just or primarily the Other, a mirror reflection for the Greeks to define themselves against. Looked at from one point of view, the peoples of Asia were ‘them’, most forcefully declared in beleaguered Asia Minor; however, they were also part of ‘us’ as fellow-actors in the world and in relationships with the gods.

A post-war Other

Even after the Persian Wars, the barbarian was not just Other. Just as the awareness of difference before the Persian Was is often understated, the power and pervasiveness of the stereotyping of the non-Greek as Absolute Other in the post-war period is generally overstated. What we find instead is remarkable thematic continuity across both periods. Indeed, the question needs to be asked whether the Persian Wars actually did form a substantial break between periods, even though they do seem to mark a strengthening of a particular position and idiom.

Despite the intensity of the Greek/barbarian polarity in the play, even in the Persians the apparently simple categorization of Self and Other was being complicated, as Aeschylus hints at traditional concerns about human relations and poses a question about the universality of not only human experience in general, but the human experience of the divine (see further chapter 5). However, by the 460s and the production of the Suppliants, Aeschylus and his audience are ready to probe in a deeper way whether Greeks and barbarians really were such opposites. Although most commentators see such a shift coming much later in the century in the work of Euripides, already in the Suppliants Aeschylus sets out to question and undermine the polarity and complicate the relationship between the Argives, and Egyptian Danaids, who trace their descent from Argive Io, and, on this basis, ask the Argives for sanctuary from their cousins, the sons of Aegyptus, who wish to force them into marriage. While it is generally agreed that the major theme of the Suppliants, and of the trilogy it belongs to, is marriage (whether it is marriage in general, marriage to the sons of Aegyptus, or an endogamous marriage to cousins) another strand of the saga of Io and her descendants, which had already assumed importance in the archaic period, was revived in this play and given a new significance: the relationship of the Aegyptiads and the Danaids to the Argives.51

For the Danaids are both Self and Other. Danaus and his daughters, as well as the sons of Aegyptus, are described as different from the Greeks, using motifs familiar from the Persians, especially the violence, luxuriousness and exoticism of Asia.52 Nevertheless, despite appearances, the Danaids are also ‘insiders’ who have a positive right to supplicate the Argives because they are descendants of Io (16–19, 274–6, 291–324). Pelasgus, after hearing the whole story of their descent, accepts their ancient claims of kinship (325–6), as do the Argives (cf. 632, 652). Furthermore, they are acceptable as insiders since they have ‘Hellenic’ aspects: in particular, they are modest, and, unlike the Egyptian herald, honour Greek gods, and call on Zeus (210, 212), Apollo (214), Poseidon (218) and Hermes ‘according to the customs of the Greeks (Έρμης ὅδ’ ἄλλος τοίσιν Ελλήνων νόμοις)’ (220). In fact, Pelasgus, the Argive king, sums up the ambiguity of their position when he calls them astoxeinoi, citizen-strangers (354–8).53

The dual role of the Danaids as insiders and outsiders seems to be fundamental to the play, and probably was for the trilogy also. Non-Greekness, and a non-Greekness which is described in ‘barbarian’ terms (although, astoundingly, the word barbaros is used only once in the play, and then to describe the Danaids’ clothing, at line 235; otherwise they are epēludes, ‘incomers, strangers’), is brought right to the heart of Greekness. Not only are the Danaids accepted as kin of the Argives, but also it is implicit in their story that from the marriage of Hypermestra and Lynceus the Argive royal line will be founded. The Danaids are dark skinned and exotic, yet they are kin of the Argives, as, by implication, are their violent cousins.

The action of the play is set in Argos, which, according to Zeitlin, is Athens’ alter-ego, and acts in general terms as the middle ground between Athens and the anti-Athens, Thebes.54 While Thebes becomes a closed and confined mythic space in which the Athenian audience can watch re-enacted ‘these same intricate and inextricable conflicts that can never be resolved and which are potentially present for the city of Athens’, Argos is the city of redemption, and provides possibilities denied by Thebes.55 It is ruled by Pelasgus, ‘a model king, just like Theseus, and a democratic city that closely resembles the Athenian ideal’.56 It, like Athens (and Thebes), boasts autochthonous origins. Aeschylus – and here he is being original – makes Pelasgus the son of agēgenēs (‘earth-born’), Palaechthon, ‘Ancient Earth’, although Acusilaus before him had already made Pelasgus Argive (FGrHist 2 F 25).57 The Athenian audience is also helped to identify with the daughters of Danaus by their singing of ‘Ionian songs’ (Tαόνιοι νόμοι 69), surely at least a double pun, alluding also to the Danaids’ descent from Io (the Argives in the fifth century claimed Dorian antecedents). For Calame the trilogy, by the ‘refounding’ of Argos through the union of Lynceus and Hypermestra, reworks for the Athenians their autochthonous origins, providing within the context of the ideological rhetoric of ‘Greeks and barbarians’ a new model for the place of Athens within a consciously united Greece in the post-Persian- Wars world.58 It might also be argued within a ritual and civic context that the play is concerned with the incorporation of ‘the Other’ within civic and ritualized structures of the Athenian polis.59 However, the play can also be read against political and historical contexts. On this level, the Suppliants seems to represent the opening up of Athenian attitudes to the non-Greek world, or at least Egypt, since only a few years later the Athenians were involved (ultimately disastrously) in the Egyptian revolt from Persia, which was set in motion by the Libyan Inaros (Thuc. 1.104). Nevertheless, in the play the Aegyptiads are straightforwardly, stereotypically and negatively ‘barbarian’ (although they are never given that name), and even the Danaids are not represented in a wholly positive light and by no means represent a ‘Greek face’ of barbarity. What can be said, however, is that it was possible to question the stereotypes, and to propose in strong terms a level of intimacy with the non-Greek world, while at the same time asserting difference.

In other contexts too, the non-Greek was not always just a negative stereotype, and in the post-wars period there was considerable and positive interest in non-Greek culture. For example, books were compiled on a variety of non-Greek cultures: Scylas of Caryanda wrote the first description of India; Dionysius of Miletus wrote a Persika, as did Charon of Lampsacus; Ion of Chios wrote his Epidēmiai about his travels in Asia; while, among the contemporaries of Herodotus, Xanthos of Lydia composed a Lydiaka, Hellanicus a Phoenikika, a Cypriaka, an Egyptiaka, a Persika, a Scythika and a Barbarika nomima (Barbarian customs), and at the very end of the fifth century and beginning of the fourth Ctesias compiled his Persika.60 Choerilus of Samos also wrote the epic poems Barbarika, M̑dika, and Persika. As well as his two ‘historical’ tragedies, Fall of Miletus and Phoeni- cian Women, Phrynichus wrote tragedies called Aegyptians, Antaeans or Libyans and Danaides. Aeschylus wrote, in addition to Persians, Aegyptians and Danaides, Carians, a Memnon, Mysians, and a Phrygians. There are also a number of lost comedies with suggestive names such as Chionides’ Persians, Pherecrates’ play of the same name, and Magnes’ Lydians. Athenian literature is also littered with references to exotic places, animals, artefacts and customs:61 for example, peacocks, prostration, the cock (as Tuplin notes ‘the other Persian bird’), lucerne (‘Persian grass’), fly whisks, eunuchs, and various items of Persian clothing. As Miller has shown in great detail, in the fifth century the Athenians also adopted, incorporated and adapted Persian artefacts, including Persian styles in cups, bowls, and parasols, as well as styles and designs in clothing as fashion statements and status indicators.62

The visual and plastic arts also show an interest in non-Greeks. From the archaic period differentiated clothing and physical characteristics for Thracians, Scythians, Persians, Egyptians and Ethiopians are represented in Greek vase-painting.63 Non-Greeks are also given stereotypical characteristics on painted pottery. While heroic figures such as the Ethiopian Memnon were generally depicted as if they were Greek heroes, the Ethiopian attendants of Memnon were shown (however inaccurately) with snub noses, thick lips, and frizzy hair.64 Similarly, the Egyptian context for the Bousiris myth is clearly marked until about the 460s, either by dress, or by an attempt to create an ‘Egyptian’ physiognomy, with snub noses, thick lips and shaved heads (Fig. 1, p. 56).65 Surprisingly rare, representations of conflicts between Greeks and Persians in the first half of the fifth century pay close attention to the ethnographic detail in the combatants (Fig. 3a–b; note that all figures, Greek and Persian, are fully clothed).66

Fig. 3. Red-figured cup, depicting Greeks and Persians fighting, c. 490 bc (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford 1911.615; photograph courtesy of the Museum).

Other representations of non-Greeks also show an interest in ethnic detail. A moulded cantharus in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens represents the heads of two women, one Greek and the other Negroid, dating to about 490 BC(Figs. 4a–c), in which the Negroid head is portrayed stereotypically as black with white hair, snub nose and thick lips (just as indeed the Greek woman is also stereotypically white with contrasting long straight nose and softer facial planes). Certainly this vase shows an interest in antithesis (particularly the striking opposition between black and white), but there is not necessarily any moral or hierarchical loading in the representations, and there seems to be a developed ethnically-based aesthetic and interest in different kinds of beauty, since the Negroid woman is by no means caricatured and is striking for the softness, voluptuousness, and yet regularity of her features.67 In fact, the ‘joke’ in this vase at least is the ‘simple’ shock of ‘black’ and ‘white’, rather than any qualitative differentiation of ‘black’ and ‘white’. Possibly more morally loaded are the male/female head-vases of the same type, or the female/satyr vases, which oppose gender in a similar way. As Lissarrague points out, the context of the symposium probably ‘loads’ the meaning of the vases.68 While male symposiasts may have been shocked by drinking from the bisexual cups, the allure of the bi-ethnic cups would have had a different impact. Although gender norms may have been overturned, the female heads have more the impact of a sensual and sexual provocation than of an affront.

Figs. 4a–c. Moulded cantharus representing the heads of two females, one Greekand the other Negroid, janiform arrangement, c. 490 bc (National Archaeological Museum, Athens 2056; photographs courtesy of the Museum).

‘War against the barbarians’

However, at the same time as the Greeks were expressing ambivalent ideas about barbarians, or at least some barbarians, the ideas of the Asian barbarian as wealthy, exotic, luxury-loving and tyrannical had already developed in the seventh and sixth centuries, and the war against Asia was also forming in Greek thought. There is some evidence that it may have started gaining shape prior to the Ionian revolt. As Herodotus describes it, the Ionian Revolt seems to be a straightforward Panhellenic venture, and Aristagoras’ speeches at Sparta and Athens voice Panhellenic themes.69 At Sparta (Hdt. 5.49), Aristagoras tells Cleomenes that the Greeks of Asia Minor are ‘slaves’ and not ‘free’. He claims that involvement in the revolt is a special duty of the Spartans because they are ‘leaders of Greece’,70 and rallies them by the ‘gods of the Greeks’ to ‘rescue the Ionians, men of the same blood, from slavery’. He also tries to persuade the Spartans by enticing them with the rich pickings that are to be had from Asia: gold, silver, and bronze, and fancy clothing, beasts of burden and slaves; for the barbarians have more good things than all the others put together! He finishes by asking how, if it is possible to rule Asia, they could choose to do anything else. At Athens, he says the same things, only adding that the Milesians were colonists of the Athenians, and it would be fitting to save the Ionians and their money (Hdt. 5.97). While, at first glance, these sentiments might seem appropriate to a Panhellenic war, they are probably anachronistic. Nevertheless, at Athens ‘liberation’ from tyranny and the establishment of isonomia may well have become a catch-phrase soon after the expulsion of the tyrants in 510, which gives some credibility to Herodotus’ reporting of the unrest prior to the Ionian revolt in terms of a call for equal treatment.71

Whatever its level or stage of expression before the Persian Wars, as a result of the Persian invasions, the barbarian war became an important Panhellenic theme, and the Trojan Wars as well as a sequence of other mythical wars, such as the war between Thracian Eumolpus and the Athenians, or, later, the war between Heracles and the Trojans, were recast as Greek wars against barbarians. The Persian Wars, however, ensured that, whatever other ‘barbarians’ the Greeks might confront, the Persians became the enemy –and the threat –par excellence.

Fear of this barbarian threat gave a political power to the representation of the barbarian and the idea of barbarian war. Especially at Athens, public buildings, such as the Parthenon or the temple of Athena Nike, were decorated with images of Greeks fighting non-Greeks, whether Amazons or Persians. However, as well as this more obvious iconography of hostility to Asia and Asian barbarians, there was also an ‘internalized’ representation of the ‘barbarian’, and especially the barbarian tyrant King, with which the Athenians theorized democratic practice and democratic concepts. But as we shall see, this theorizing of barbarian monarchy, and the concomitant theorizing of democracy itself, cut in more than one direction; neither the representations of the barbarian monarch, nor of Athenian democracy, were simple or straightforward.

In the next sections, we will consider in more detail the idea of the ‘barbarian’ as the natural enemy, as well as the associated fear. We will then turn to the Athenian political representations of themselves, as well as to democratic theorizing in Athens, and see how these Panhellenic themes interacted with each other, and the multiple and sophisticated ways in which the Athenians deployed them not only to explore their relationship with others, both Greek and barbarian, but also to give a theoretical shape to their own institutions and to democracy itself.

Barbarians as the natural enemy

The Greek, and especially the Athenian, victory over the Persians was constantly revisited and recelebrated. Timotheus’ nome (a poem sung to the accompaniment of a lyre), the Persians (frs. 788–91 Page PMG ), composed probably after 412/11 and about the battle of Salamis, makes great use of the vocabulary of barbarism in terms that show its dependence on Aeschylus’ Persians.72 A festival was celebrated annually for the victory at Salamis and perhaps also at Plataea (cf. Diod. 11.29.3 and chapter 3). In addition, paintings within the Stoa Poikile depicted the Athenian victory over the

Persians at Marathon (Paus. 1.15.3), although they also probably represented Athenian victories over other Greeks as well (see further below).

Indeed, the barbarian as the natural enemy had become an important rhetorical figure, and was raised to the level of ideology; consequently, within the framework of the barbarian war, it is central that the cycle of war continues (Isoc. 12.163; Dem. 21.48–9). Furthermore, the barbarian is always looking for an opportunity to exploit Greek weakness (Isoc. 4.155: ‘Whom among us have they not wronged? At what time did they desist from plotting against us ?’), the Greeks must constantly seek revenge for barbarian ris (Isoc. 4.181–2; 12.61, 83, 160, Epist. 9.19), and the Greeks’ anger towards the barbarians is everlasting (Isoc. 4.157). Isocrates warns that the right time to strike is while the King is weak (cf. 4.138–56, 160–2), since with the King’s position in Asia strengthened ‘it is necessary to be quick and not to waste time, so that we might not suffer what our fathers suffered’ (4.164).

The archaic image of the luxury-loving and violent barbarians who were also proficient with drugs and magic was also developed in fifth- and fourthcentury literature. Aristophanes has great fun with Athenian ambassadors ‘dying’ of luxurious living at the Persian court (Acharn. 61–90). In the Iphigeneia at Aulis, Paris comes to Sparta ‘flower-bright in raiment, and shining with gold, barbarian luxury’ (73–4). Likewise, recalling Circe (among others),73 Euripides’ Andromache is accused (though falsely) of making Hermione childless and hateful to her husband with drugs (Androm. 32–3), and Medea kills Glauce with a poisoned wedding gown (Med. 1156–202). In the Helen Theoclymenus the Egyptian king threatens to kill all Greeks that come to Egypt (155, 468, 778, 1173–6), while among Iphigeneia’s Taurians the sacrifice of Greeks to Taurian Artemis is described with blood-dripping detail (IT 72–6). We have already seen how Xenophon in the fourth century borrows from the stereotypical contrast between simple Greek and luxury-loving Persian to heighten the dramatic tension in his description of the meeting between Agesilaus and the Persian satrap Pharnabazus at Dascyleium in 395, and in the Anabasis worries that the experience of Asian luxury might have the same effect on the Ten Thousand as the lotus did on Odysseus’ companions (see chapter 1).

While the barbarians are more cruel in punishing free men (ἐλεύθεροι) than the Greeks are their household slaves (Isoc. 4.123), Isocrates is clear that the barbarian was not necessarily a difficult enemy to overcome (5.139, cf. 4.140–3; Dem. 8.24), and Cawkwell has argued that this thought is behind Herodotus’ representation of the Persian efforts in the Persian Wars.74 Xenophon exhorts the army of the Ten Thousand to remember that Greeks are better than Asians at putting up with the extremes of heat, cold and hard work, and are also more courageous (Anab. 3.1.23). In fact, Xenophon has Cyrus say that the Ten Thousand should find the Persian army to be not of the same calibre as the Greeks, and that he chooses Greeks in his army over barbarians because Greeks know freedom, adding, ironically and in a backward reference to Herodotus, that he, Cyrus himself, would rather have ‘freedom’ than all the possessions that he has (Anab. 1.7.3–4; cf. Hdt. 1.1.26–7). Likewise, Arrian, in self-conscious imitation of Xenophon, has Alexander say to his commanders that the Medes and Persians will be easy to overcome since they were people long used to luxurious living (Anab.

2.7.4–5; cf. 8–9).

Yet the barbarian was not congenitally weak. For Isocrates he is weak because of his lifestyle. The barbarian ‘is soft and inexperienced in war and destroyed by his luxurious lifestyle’ (5.124). In the Panegyricus it is the Persians’ constitution and their lifestyle that are at fault:

None of these things happened for no reason, but all these things came about naturally. For it is not possible that those reared in this way and living under this kind of constitution could either share in any other virtue or in battle raise up a trophy over their enemies. For how could a clever general or a worthy soldier be produced among these practices of theirs ? Most of their number are an undisciplined mob inexperienced in danger, who give way in the face of war, and are better trained for slavery than are servants in our country. Those among them of the highest repute live their lives neither with a view to equality nor the commonality nor the political life, but pass through life being violent to some and being enslaved to others as men who are most perverted in nature. They pamper their bodies because they are rich, but are humbled in soul and afraid because they live under a monarchy, are passed for review at the royal palace itself, prostrate themselves, and practise humbling themselves in every way, doing obeisance before a mortal man but declaring him a god, and paying less attention to the gods than to men.

(4.150–1)

Similarly Herodotus and the author of Airs, Waters, Places had blamed both political constitutions and soft-living for the moral and physical weakness of those living in Asia.75 Isocrates’ thinking here also seems to be close to the views of Plato and Xenophon, who attribute the failings of the Persian empire to education and wealth (Plato, Laws 3.694c–696a; Xen. Cyrop. 8.8.15–20). Yet even the environment can educate. Isocrates also claims that the soil of Athens rears better men than the rest of the world (8.94), and in the Menexenus (237a–239a) Plato ironically complicates the relationship between environment and education by using the metaphor of Attica as the ‘mother’ who looks after her children, providing both for their sustenance and their education in equality. Nevertheless, Isocrates is drawing on a similar rhetorical formula (if not a similar thought) when he says in the Areopagiticus that ‘our land is able to bear and rear men who not only in skills and deeds and words are the most naturally good, but also far excel in manliness and virtue’ (7.74). Thus it is culture with nature that has led to the success of the Athenians. However, as Briant points out, for Plato and Xenophon, Persian decline was a result of the falling away of traditional educational practices while for Isocrates it is the education process itself that is the problem.76 Plato suggests that the Persians could have rescued their empire if they had resisted the temptations of the good things which empire brought them. This means that for Plato (as indeed for Xenophon) the Persian could be a noble figure worth emulating, and Plato points in particular to Cyrus the Great who allowed ‘a measured balance between slavery and freedom’, so that ‘first they became free, and then became masters of all the others’ (Laws 3.694a). We will return to Cyrus later on.

Certainly, non-Greeks and their customs could be caricatured and maligned. The speech of the Persian ambassador in Aristophanes’ Acharnians is designed not only to indicate his foreignness but also to make him ridiculous (100–10), just as the image of the Persian King defecating on his golden hills demeans and reduces his eminence (80–2). Similarly, in Birds the foreign god Triballian (the Triballi were a Thracian tribe) is said to be ‘the most barbarous of all the gods’ who does not know how to dress himself properly and who twitters unintelligibly like a bird (1565–74, 1615, 1628–9, 1678–82).

In the visual arts as well as in literature the barbarian could be ridiculed and set against an ideal of Greekness. On the Athenian pelike dating from about 470 depicting Heracles’ defeat of the servants of the Egyptian Bousiris, the clothing of the Egyptian priests is pulled away to reveal swollen and pendulous sexual organs that contrast with the small, neat members of the hero (Fig. 1).77 There are other examples of possible caricature, though sometimes the moral dimension of the representation is as much the subjective projection of the viewer as the creator, and not everyone agrees that these representations of non-Greeks are necessarily designed for ridicule. Lissarrague, for example, cites as examples of caricature a moulded janiform cantharus (one of the series of so-called ‘Head Vases’ discussed above) from the necropolis of Acanthus, in the Collection of the Museum of Polygyros, pairing a beautiful European female face with a caricatured Negro male with prominent teeth (Figs. 5a–c; the inscription also suggests an ironic juxtaposing of the two heads: ‘I am Timyllus, as handsome as this face’, ‘I am Eronassa, very beautiful’),78 and the small sculpted vessels, rhyta shaped like pygmies with grotesquely dwarfish bodies, pronounced Negroid features and extended genitalia (see, for example, Figs. 6 and 7).79 Bérard, on the other hand, objects to a ‘hierarchical ranking’ in the implied antithesis of some of the moulded Head Vases, and, citing the example of the cantharus from Acanthus, comments on the balanced treatment of and lack of caricature in both heads, claiming that this is true for the whole series.80 Similarly for the representation of the pygmy and crane (Fig. 6), while it is true that the genitalia of the pygmy are distended (perhaps in the manner of old men more generally in Greek art) and the body squat and limbs thickened, the pygmy himself is fine featured with thin lips and fine aquiline nose (unlike the representations of Negroids), and the figure is carefully delineated and laughing. As a result, although the representation of the pygmy and crane compositionally is comic, the viewer perhaps laughs with the pygmy rather than at him. In relation to another vase in the ‘Pygmy series’ representing a young boybeing bitten by a crocodile (Fig. 7), Lissarrague concedes that although the composition is cruel and the boy is black, he is treated sympathetically, and there is no suggestion of dwarfism or physical deformity.81

Figs. 5a–c. Moulded cantharus depicting two heads, one female (European), one male (Negroid), janiform arrangement; inscribed: ‘I am Timyllus, as handsome as this face’, ‘I am Eronassa, very beautiful’ (Collection of the Museum of Polygyros; photographs courtesy of the 16th Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities, Thessaloniki).

Fig. 6. Pygmy rhyton, representing pygmy and crane, c. 460 BC(Institut für Klassische Archäologie und Antikensammlung, Erlangen P 1; photograph by G. Pöhlein; courtesy of the Institut).

Fig. 7. Pygmy rhyton, representing boy being eaten by crocodile, c. 460 BC(Staatliche Kunst- sammlungen Dresden, Rhyton des Sotades; photograph courtesy of the Staatliche Kunst- sammlungen).

In fact, it also seems that Negroid features were not necessarily in themselves an object of ridicule, and the response to these vases was varied and even multi-valent, in that they were open to multiple interpretations. A moulded aryballos from the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, this time in the shape of a Negroid man (Fig. 8) dating to the sixth century, shows a decided interest in his Negroid features (full lips, frizzy hair, high cheek bones, broad nose and lustrously black skin), but not to caricature them for their own sake. The vase is inscribed with the words ‘Leagrus is handsome’, satirically suggesting a contrast between the vase’s owner and his pot. But, while the contrast provides the joke, the response to the vase suggested by the inscription (though integral to the decoration of the pot) is in some sense of a secondary order since the features of the Negro are in no way deformed but are treated with sympathy. Indeed, we have already discussed another janiform cantharus which seems to represent Negroid features as beautiful, even if beautiful in a different way, and this is not the only vase which contrasts different kinds of beauty (Figs. 4a–c above).

Fig. 8. Moulded aryballos representing Negroid male (inscribed: ‘Leagrus is handsome’), 6th century (National Archaeological Museum, Athens 2385; photograph courtesy of the Museum).

Figs. 9a–b. Attic red-figured oinochoe depicting naked Greek holding erect phallus, and clothed Persian archer; inscribed: ‘I am Eurymedon. I stand bent over’, c. 460 Bc (Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg Inv. no. 1981.173; photographs courtesy of the Museum).

One of the most notorious vase-paintings depicting a Greek and Persian, in Hamburg and dating to about 465 BC,shows a semi-naked Greek holding his erect penis in his hand pursuing an exotically clad Persian bent over as if ready to receive his erotic attention (Figs. 9a–b). The vase bears the inscription, ‘I am Eurymedon; I stand bent over’, which is generally assumed to contextualize the vase against the background of the Athenian defeat of the Persians at Eurymedon in 467 or 466 (Thuc. 1.100.1), and so to represent, through the Persian’s sexual submission, political and military submission. Lissarrague, for example, says of the vase and its inscription: ‘This is simultaneously an obscene and a political witticism: his position is that of a man about to be buggered; the Persian’s gesture implies defeat and its sexual equivalent; militarily he is vanquished, sexually possessed.’82 Other, less triumphalist, interpretations have also been offered which undermine the immediacy of the suggested sexual victory and the effeminacy it is said to imply.83 Yet it is difficult to deny the aggressiveness of the Greek and the passivity and subordination of the Persian.

However, in the first half of the fifth century, the ‘Eurymedon vase’ represents the exception rather than the rule in representations of Greeks and Persians. In Greek vase-painting, responses to barbarians and barbarism are complicated and varied. Of the surprisingly few scenes depicting Greek/ Persian conflict, in the early post-war years Attic vases can show Greeks fighting Persian warriors in equal struggle, Greeks in a strategically advantageous position, as well as barbarians (including Persians) defeating Greeks.84 It is not until after about 460 BC that there is a change: the Greek is portrayed as a naked hero, and the Persian, still fully clothed, is shown in flight.85 Good examples of this new depiction of the relationship between Greek and Persian are the lost wall painting from the Stoa Poikile representing the battle of Marathon (Paus. 1.15.3) and a mid-fifth-century oinochoe attributed to the Chicago Painter, in which the nude hoplite (complete with helmet, shield and greaves) bears down with his spear on the Persian archer who turns in flight and whose arrow has already passed the Greek (Fig. 10).86 Nevertheless, as Bérard notes, although the painter takes care with the ethnographic detail, the Persian on the vase is in no way caricatured or denigrated.87 While at this point in the mid-fifth century there certainly is a significant movement in the depiction of Greeks and non-Greeks (and especially in the relationship between Greeks and Persians), and a tendency to create a moral difference between Greek and non-Greek, these developments should not be overstated. Other developments around the mid-fifth century indicate different directions: for example, Raeck makes the point that from the 460s barbarians can be shown striking Greek attitudes, and in situations which had previously been reserved expressly for Greeks, such as warrior departure scenes.88

Fig. 10. The Chicago Painter; Athenian red- figured oinochoe with Greek hoplite attacking Persian archer, c. 450 BC; height with handle: 24 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Francis Bartlett Donation of 1912, 13.196; photograph © 2006 Museum of Fine Arts

Fear of the barbarians

The imagery of the Eurymedon vase is powerful because it confronts and then subverts the fear of the aggressor, which had once – famously, notoriously and concretely – been the Persian. It is the fear of the enemy, which is also behind the caricature of the barbarian as a means of controlling it, both the enemy and the fear. Fear of the barbarian was an important element in the Panhellenic war against Asia. Thucydides says that the Delian League was formed in 478/7 out of fear of the barbarian (1.75.3, 76.2). Even after the immediate Persian threat had simply subsided or formally been removed through the Peace of Callias, the threat was a powerful force in the Greek imagination. Lysistrata, in the play named after her of 411, says to the Athenians and Spartans:

I want to reproach you both together, and I do it

justly, you who besprinkle altars

with the same holy water like kinsmen

at Olympia, Thermopylae, Delphi –How many

others could I name if I had to go on? –

and who while the enemy is at the gate with a barbarian army

destroy Greek men and cities.

(1128–34)

The threat lies in the fact that the barbarian who attacked once before could always attack again. It is on this basis that Iphigeneia in the Iphigeneia in Aulis comes to justify her sacrifice in order to put a stop to the snatching of Greek wives.

At the end of the fifth century fear of the barbarian not only had rhetorical force, but also had become institutionalized as part of civic culture, and prayers against the Mede seemed to have been included among the normal practices of the assembly. In Thesmophoriazusae of 411 one of the assemblywomen utters imprecations on anyone who ‘plots any evil against the people or the women, or makes any approaches to Euripides and the Mede for any harm against the women’ (334–6) as do the Chorus against ‘all women who lie and transgress the customary oaths, or seek to reverse the decrees and laws or disclose secrets to our enemies, or to the Mede for profit or for doing harm...’ (357–60). In the fourth century, Isocrates in the Panegyricus says that ‘our fathers condemned many to death for medizing (μηδισμός), and even now in our assemblies before anything else they call down curses on any of the citizens who makes proposals for treating with the Persians’ (4.157).

In fact, fear of the barbarian was a clichē in the fifth century. Aristophanes in the Knights of 424 has the Sausage-seller accused of conspiring with the Mede (Knights 478), in Wasps of 422 Sosias the slave complains that ‘some Mede is attacking my eyes’ ( Wasps 11–12), and in Peace of 421 Trygaeus uses the fear that barbarian gods will supplant Greek gods to persuade Hermes to help him (Peace 403–13), and threatens to indict Zeus for betraying the Greeks to the Mede (Peace 107–8). Actually, throughout the 420s the Persians were involved at Athens, but only in a positive way and at the behest of the Athenians. Aristophanes’ Acharnians of 425 satirizes diplomatic exchanges with the Persians, suggesting that Persian ambassadors may have been quite familiar to the Athenian public and Athenian embassies to Susa were regular enough to be ridiculed as a well-paid sinecure (61–125).89

Isocrates, Demosthenes and Plato also exploited the topos that enmity of all Greeks with the Persian was both natural and implacable (e.g. Isoc. 4.73, 157, 184; 12.42, 102; Dem. 14.3, 15.6; Plato, Rep. 5.470a–c). Plato says in the Republic that ‘we say that when Greeks fight barbarians and when barbarians fight Greeks it is war (πολεμείν) and they are enemies by nature (πολεμίους φύσει εἶναι), and that this enmity must be called war (καὶ πόλεμον τὴν ἔχθραν ταύτην κλητέον, Rep. 5.470c). The logic followed that if the Greeks were going to fight wars, they should be wars against the enemy by nature. Isocrates declares ‘it is much more noble to fight the King about his empire than to wrangle with each other about the leadership’ (4.166). Demosthenes’ speech On the Symmories, of 354/3, set out to persuade the Athenians not to undertake a war against the King (which they did not –although not necessarily as a result of Demosthenes’ persuasion since he did not carry the point about the symmories), despite rumours (this time true) that the Persian was threatening to launch an attack on them in retaliation for their involvement in the revolts in Egypt. Isocrates’ Philippus of346 also suggests that there was still talk of a Persian invasion (5.76). Nevertheless, Isocrates and the others knew that the friendship of the Persians had proved useful in Greek power-struggles (Isoc. 5.42), though Plato chooses to argue, happily ignoring the Athenians’ part in Persian negotiations, that the other Greeks from jealousy of Athens ‘dared to call on our most hated enemy the King...and summoned together against our city all the Greeks and the barbarians’ (Menex. 243b).

The Greeks were afraid of the Persian threat, or at least that is what they claimed. But by the late-fifth century was the enemy in fact at the gate with a barbarian army? By the time the Lysistrata was produced in 411 the Persians were deeply implicated in Greek affairs, and much of the rhetoric of the fear of the barbarian from the second half of the fifth century needs to be set against the fact of almost continuous negotiations by Greek states with the Persian ‘enemy’ in pursuit of Persian support either in the form of money or military action.

‘Barbarian’ tyrants at Athens

But fear of the barbarian, or at least ‘barbarian things’, could also have ideological advantages. This was especially true of barbarian tyrants, of which, in particular, the Athenians were afraid, at least conceptually. Tyranny had long been associated with Asia, but it had also had a long association with the Athenian political consciousness. Solon, in the early-sixth century, had not only rejected tyranny for himself, but also warned against the ease with which the dēmos would turn to the ‘slavery of monarchy’ (Solon fr. 9 West IE2 ), and the removal of the Peisistratidae by the ‘tyrant-slayers’ was celebrated before Xerxes ever reached Athens (though Raaflaub argues that the end of tyranny was not conceptualized as ‘liberation’, eleutheria, until after the Persian Wars).90 However, tyranny seems to have solidified in the Athenian mind as a peculiarly barbarian and Persian institution with the production of Aeschylus’ Persians in 472 BC.Here the Persian King stands not only for barbarian slavishness (176–99, cf. 241–2) but also against freedom of speech (584–96).

Later in the century, Herodotus makes great play with Persian enslavement, Persian tyranny, and tyrannical rule, since for Herodotus life under a tyrant meant slavery.91 When Hydarnes the Persian offers to the two Spartans, Bulis and Sperthias, the rule of Greece as a gift from the King, they reply:

Hydarnes, the counsels you present to us are not of equal value. You give advice about some things having tested them, but in others you lack experience. For you know well how to be a slave, but are not at all experienced in freedom, or know whether it is sweet or not. For if you tried freedom, you would not counsel us to fight for it just with spears, but with axes too.

(Hdt. 7.134–6, esp. 135)

Crucially, Herodotus sees the contrast in the nomoi of the Greeks and Persians as explaining and indeed determining Greek success and Persian failure.92 The Spartan Demaratus explains to Xerxes the reasons for Spartan success in terms of the rule of law: ‘They are free – yes –but not entirely free; for they have a master, and that master is law (νόμος), which they fear more than your subjects fear you’ (7.104.4). On the other hand, Herodotus claims that Athenian strength lay in their equality of speech (ἰσηγορία), and that the Athenians had grown in strength once they had rid themselves of the tyrants:

This clearly shows that while they were oppressed they were slack in their duty like those who work for a master (δεσπότης), but once they were liberated each man was eager to work for his own benefit.

(5.78)

In addition, Herodotus explains the Spartans’ attempt to reinstate the tyrant Hippias at Athens in these terms, saying that since the Athenians had grown in strength the Spartans thought to restrain them by means of tyranny so that they would be weakened and ready to be obedient (5.91). For Herodotus, the strength of Athenian democracy was that it was within law and that it was accountable before the whole people (3.80). A monarch, on the other hand, even a good one, because he lacks restraint, either internally or externally, will naturally fall into evil and tyrannical ways.

Euripides also comments on tyranny and its relationship to the rule of law.93 In Euripides’ Suppliant Women (late 420s),94 in the exchange between Theseus and the Theban herald, the Herald in criticism of democracy argues that a city needs specialist guidance and people who have the leisure to rule it, and that in a city ruled by one man there is no one who ‘stuffed with words, turns the city now this way now that for private profit’ (409–25).95 To this Theseus replies:

There is nothing worse for a city than a tyrant.

In the first place where there are not common laws (κοινοί νόμοι),

but one

man rules and law resides in his own person, there is no longer equality.

But where the laws are written down, the man who is weak

and the one who is wealthy have equal access to justice (δίκην ἴσην ἔχειν)...

and the small man with right on his side defeats the great man. This is freedom [when it is declared]: ‘Who desires to bring some good plan

for the city to the assembly?’

Whoever desires to do this is famous; he who does not want to

is silent. What is more equal for the city than this?

And indeed where the dēmos is manager of the land,

it delights in young men near at hand.

But a man who is king considers this hateful,

and the best element, whomever he considers to have sense,

he kills, fearing for his tyranny.

(429–46)

Here Euripides makes explicit the difference between the rule of a tyrant and the rule of law, in terms similar to those that Aristotle was to formulate in the next century (Pol. 9.1295a7–17): that laws (νόμοι) which were written down and common to all gave everyone equal access to justice (compare Plato’s Hippias for whom law is a tyrant, τύραννος, which constrains them contrary to nature: Protagoras 337c–e). This seems to have been Herodotus’ point also, though probably with an element of satire, when he referred to the despotēs nomos, ‘law the despot’ (7.104.4). A tyrant acted in his own interests, and his subjects responded with fear. Law, on the other hand, by its equality and impartiality served the interests of all, and, bringing justice, was the more compelling for that. Similarly, in the Phoenician Women, Eteocles denies the reality of equality and says that he will have Tyranny at all costs, and that he will not give it up, but will do things which are wrong if need be in order to keep it, even though his mother pleads with him to honour ‘Equality’ ‘since this always binds friends to friends, cities to cities, and allies to allies’ (cf. chapter 3). Tyranny looks only to itself, whereas ‘equality’ is part of the natural order and pattern of life.96 On the other hand, in the Heracleidae of about 430,97 Demophon says that tyranny has no place in the Greek world, but only belongs to the world of the barbarians (423–4; cf. 411–13). Nevertheless, in Euripides’ Andromache the Spartan Hermione, bedecked in gold and jewellery, announces that money can buy freedom of speech (ἐλευθεροστομείν, 153).

The developing notion in Greek thought of political freedoms and the rule of law was expressed particularly (although not exclusively) through the movement towards radical democracy at Athens. At the same time, it was also structured by the antithesis of ‘slave’ and ‘free’, and was represented by the antitype of the Persian King. To be ‘enslaved’ was to be deprived of equality, a value necessary for the happy life of the polis. This may be one message of the oinochoe depicting the naked hoplite attacking the Persian warrior discussed above (Fig. 10). In the context of the Athenian victory over the Persians at Eurymedon the heroic naked hoplite, a powerful emblem of democracy (for Pindar at least the ‘rowdy army’ represented rule of the many: . 2.87), both morally and physically defeats the clothed Persian.98 Rule by one man was problematic because it created hierarchies before the law (as Theseus makes plain to the Theban Herald in Euripides’ Suppliants). The Persian King, on this basis, was seen to typify the rule of tyrants, whatever the political realities of his rule, because he was associated at an early date with the loss of political equality. Both monarchy and the rule of law were ‘enslavement’, but whereas the one produced political inequality the other produced equality. In this way, Greek constitutional rule, and especially Athenian democracy, could be defined through its opposite, Persian tyranny, which removed freedom and stood outside law.99

Thucydides is also interested in monarchs and tyrants,100 and uses to great effect Panhellenic motifs both to work through and to criticize the Peloponnesian War and the actions and motivations of the main players within it. In the first place, he describes the Athenian empire as a tyranny. He has Pericles say that the Athenian empire was like a tyranny, ‘which though it may seem wrong to have taken is dangerous to let go’ (2.63.2, cf. 6.83.3–4). Cleon, on the other hand, says that the Athenians’ empire is a tyranny, and that the control of the empire will result more from a show of strength against recalcitrant allies than through the allies’ goodwill (3.37.2). The case put by Cleon in explicit terms and by Pericles in more veiled ones is the same: the interests of Athens as ‘tyrant’ should be to seek its own interests over those of the allies. But this conflicts with Diodotus’ argument for a more moderate approach which sees that the interests of Athens can be achieved by treating ‘free’ states well, and by nurturing them beforehand to maintain a sense of community (3.46.4–6).101 However, Thucydides is also being ironic both in the ideas and the characters to whom he gives them, for Cleon as one of the chief among Pericles’ reviled ‘successors’ is supposed to be an ‘opposite’ to the great man. Further Cleon, in the Mytilenaean debate, argues the case for rule by law (which he defines as decrees of the assembly), even if it is bad law (3.37.3–4). Diodotus, on the other hand, argues that, although the Mytilenaeans are acting contrary to law (by revolting), they are acting according to nature, and that the issue is not what is just but what is expedient; effectively, he is urging the Athenians not to act tyrannically by enslaving the Mytilenaeans, but to set aside law for the good of the empire.102 In this double-play on constitutions within law and outside law, on democracy and tyranny, Thucydides questions and satirizes Athenian constitutional rule, its claims to rule under law, and in fact the nature and justification for the rule of law itself.103 Empathetic and appropriate handling of the allies is not consistent, it seems, with the rule of law, the clarion-call of the Athenian democratic state.

For Thucydides the tyrant and the tyrant city share the same characteristics. He says that monarchy differs from tyranny in that the former has fixed prerogatives (1.13.1), whereas the tyrant looks only to the interests and security of his own person and that of his immediate family (1.17.1). The Athenian Euphemus says at Syracuse that the characteristics of the tyrant whether city or individual are the same:

For a man who is tyrant or a city with an empire the logical course is to pursue advantage and not kinship except when it can be trusted. And in regard to each, it is necessary to choose one’s friends and enemies according to the circumstances.

(6.85.1)

Euphemus justifies Athenian self-interest and so Athenian empire in terms of security:

We say that we rule those in our empire so that we might not be ruled by another, and that we are liberating (ἐλευθερουν) those here so that we might not come to harm at their hands. We have also been compelled to do many things, because we are on our guard in many directions. We have come now as formerly to help those here who are being wronged, and not unasked but having been invited.

(6.86.2)