Perfectionism can be associated with a range of problems. It can both cause these problems and also keep them going. These may be difficulties related to the perfectionism itself or other specific difficulties including anxiety, depression, eating problems, procrastination and obsessive compulsive disorder.

This chapter will help you to understand what types of problems are associated with perfectionism and which difficulties might relate to you.

Perfectionism can cause a number of problems, as shown in Box 1.1 in the previous chapter. If you have perfectionism, you are likely to be tired (from striving all the time to achieve your goals), rather rigid and possibly isolated from other people. Perfectionism may also be causing significant problems at work. For example, if you are a teacher and you are striving for a flawless performance from your class or yourself, then this may cause friction between you and the students. Or if you are a manager, you may be responsible for giving someone their annual appraisal and, struggling for the ‘right’ words to say, stay up most of the night agonizing and then perceive that you perform less well than you wanted to in the appraisal itself. Maybe you and your partner are arguing over why you feel the necessity to rewash the dishes that have already been washed up. Maybe you can’t send Christmas cards because the effort of personalizing each one means that they are never completed on time. Perhaps you have been forced to take a year off from your studies because you can’t bear to hand in coursework that you know could be better if only you had longer to do it. Perhaps your life is ruled by ‘musturbation’ – I must do this, I must not do that. This is just a sample of the range of problems perfectionism can cause. At its core it is like a prison of rules and regulations, ‘shoulds’ and ‘should nots’ that govern every aspect of life. Buying this book is your first step in breaking free from this prison. It is for this reason that we have entitled the final chapter ‘Freedom’.

Perfectionism can be associated with a range of other difficulties. Common among these are problems in the areas of anxiety, mood and eating.*

When a person sets themselves demanding standards and feels they might not meet those standards, this often results in anxiety. Constant thinking about, or checking on, performance can lead to feeling anxious as the person starts to fear they will not achieve their standards. It is like being constantly on the lookout for any sign that his/her performance may not be up to scratch; if it has slipped, the person may become very worried, anxious and stressed as a result.

Perfectionism can lead to feeling generally nervous, stressed and on edge. But perfectionism can also be associated with specific forms of anxiety, including social anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder and obsessive compulsive personality disorder.

Most of us can relate to feeling a little nervous when we walk into a new social situation, like a big party where we don’t know many people. Social anxiety is more than just feeling shy, though: it involves a persistent anxiety about social situations, and the core part of it is worrying that you will do or say something that will embarrass you in front of others, or that others will notice that you are anxious. It also involves worrying about being the center of attention, and wishing not to be under the spotlight in social situations.

Perfectionism can both bring on social anxiety and keep it going. Often people have thoughts about the perfect way they wish to be perceived in a situation, and will berate themselves if they feel they have not met their high standards for social performance. Mark is an example of someone like this.

Mark: An example of someone with perfectionism and social anxiety

Mark was an accountant at a big firm and frequently had to attend team meetings, at which he was expected to make contributions. Mark would become very nervous and anxious before going into these meetings, fearing that he would not say things in a perfect way, or that he would be put on the spot by his boss and not have anything clever to say. He would often sweat and worry that others would notice him sweating or shaking. He would endure the meetings in great discomfort, and would spend a lot of time in the meetings going over and over in his head potential responses to questions so that he could say things in a perfect way. Often Mark would feel that he did not respond in a good way in the meetings, and that others were noticing he was anxious. He often also compared himself to other members of his team, thinking that they were smarter and had a better sense of humor than he did. When he walked away from meetings, Mark would go over everything he had said again and again, criticizing himself for not saying things in a better way, and setting his standard higher, resolving to do better next time, and aiming to appear more clever and funny at the next meeting.

We can see in Mark many of the features of social anxiety listed in Box 2.1. Being able to change your perfectionism may help diminish or banish feelings of social anxiety.

Perfectionism can be very closely linked to obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Sometimes particularly frightening and repugnant thoughts and images can repeatedly come into our minds and cause great anxiety – for example, thoughts that maybe you will accidentally harm someone or spread germs, or that something bad will happen to your family. Some people with OCD doubt whether they have performed a task ‘correctly’ or even whether they have performed it at all.

With OCD, when these sorts of thoughts keep occurring the person searches for a way to reduce the anxiety and perceived danger. One way people do this is to complete rituals which are aimed at reducing anxiety in the short term. For example, if a person keeps having frightening thoughts that their family will become contaminated, cleaning the home intensively can help him/her feel less anxious because he/she is ‘doing something’ to protect the family. In OCD these rituals (known as ‘compulsions’) are often based on very strict rules and must be done in exactly the same way each time. Perfectionism may play a role in the development of OCD because it is likely to influence both what a person makes of the unwanted, frightening thoughts that happen to all of us and how they respond in the compulsive or ‘neutralizing’ behavior. People with perfectionism and OCD often find it difficult to get to the point where they feel that the compulsions have been done properly, and so they get caught in a cycle of repeating the compulsions in a never-ending attempt to ensure that they have been done properly and that danger has thereby been reduced. This is a very exhausting cycle to be trapped in.

An example of someone with OCD and perfectionism is a person who feels that he/she must make sure every single detail of what they are saying, writing or reading is attended to in a perfect way otherwise something bad will happen to someone he/she loves. For example, when recalling an everyday event such a person might feel that it is essential he/she recounts every detail perfectly because if he/she doesn’t then this means someone will be in an accident; and when reading he/she might need to read and reread sections over and over again to be sure they have been understood and remembered perfectly, otherwise someone will fall ill. Someone with perfectionism without OCD may like and desire order, symmetry and exactness. For someone with perfectionism and OCD, the order, symmetry and arranging are likely to be accompanied by strong feelings of ‘bad luck’ if they are not done properly or very strong and unpleasant feelings of something not being ‘right’.

In OCD, these ‘perfectionism rituals’ are most often completed in order to make sure something bad doesn’t happen. Negative outcomes are avoided at all costs because the person feels that if something bad does happen it will be their fault. Being over-critical with oneself and concerned about making a mistake is common in OCD. Doubts about actions are also very common both in people with OCD and in people with perfectionism, possibly because repeated checking characterizes both difficulties and we know that repeated checking causes people to distrust their memory. People with OCD tend to take on too much responsibility for things and are prone to blaming themselves. Other examples of how perfectionism and OCD can go together can be seen in the cases of Jim, Mary and Julie.

Jim, Mary and Julie: Examples of OCD and perfectionism

Jim experienced recurrent intrusive thoughts about bad luck, and feared that if he did not do his compulsions bad luck would come to his business and family. As a result Jim felt he needed to arrange things perfectly, and would set out his business cards and papers on his desk at work in a particular very precise way over and over, many times a day, to ensure good luck. He felt that if he did not do these rituals, his business might fail or one of his children might become seriously unwell.

Mary had intrusive thoughts about leaving the door unlocked and appliances left on, and feared that if she did not check these the exact correct number of times, her family would be at risk and a burglar could hurt them or the house might burn down. As a result Mary believed that she must turn the doorknob exactly four turns to the left to ensure it was locked, and must check the iron and stove were off four times each before leaving the room. If Mary felt that she had not checked exactly the right number of times, or was interrupted when she was checking, she would start the checking rituals all over again. Unfortunately Mary often started to doubt whether she had checked exactly four times, so would then restart the checking again, and it usually took her a very long time to leave the house.

Julie had hundreds of thoughts a day that she might become contaminated with HIV, for example from using public toilets, handling money in shops, or brushing past someone who she thought might be contaminated. She believed she must wash her hands repeatedly in a perfect sequence, and dry them in exactly the right way, otherwise she would become contaminated and be responsible for passing on the disease to her family. If Julie did not wash her hands exactly right, she would need to start her ritual over again and repeat it until she felt they were perfectly clean. This would result in Julie washing her hands over and over until they were cracked and bleeding. Yet despite initially feeling better for a few moments after washing her hands, she continued to worry about contracting HIV.

A checklist of OCD symptoms can be seen in Box 2.2. If you recognize that these types of symptoms are taking up a lot of your time, you might need to consider working on changing the OCD as well as your perfectionism. You could do that by reading Overcoming Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (see the ‘References and further reading’ section at the back of this book) or by contacting your GP.

Obsessive compulsive disorder, or OCD, is different from obsessive compulsive personality disorder (OCPD). There is no special relationship between OCD and OCPD except that the abbreviations share three letters! Perfectionism is one of the elements by which OCPD is diagnosed. There is substantial overlap between perfectionism and OCPD, as you will see from Box 2.3, which shows you why people who have OCPD are also likely to be perfectionists.

You can have OCPD without being a perfectionist. For example, Jayne was very concerned with control and so met criteria (a) because of her orderliness, (c) because she felt that controlling her work was the key to controlling her life, (d) because she believed that if you were in control of your mind and morals, then this was fundamental to being in control in general and (e) because she felt it was wasteful to disregard items that might come in useful. She was also very miserly (g), so that when it came time to splitting the bill for an evening out with friends, she would bring out her calculator and calculate her share based on the number of glasses of alcohol she had drunk compared to other people.

If you are a perfectionist, you will almost certainly meet the criteria for OCPD. Take the example of Mark (pp. 21–2), who experienced extreme social anxiety. He prepared for his meetings by listing all the details of his projects to such an extent that he was unable to see the bigger picture of how they were progressing (a). Because of his perfectionism at work, he felt the need to triple-check all figures, and this delayed completion of the task significantly (b). He was devoted to work, partly because it afforded him some peace since when he was alone with his computers he did not have to engage in social contact (c). He was not particularly preoccupied with morality and he did not hoard, but he was unable to delegate tasks out of fear that they might not be done properly, resulting in his getting the blame and feeling as though he was a failure and lazy for not doing it every task himself in the first place (f). His need for perfection in his work and social relationships led him to be highly inflexible (h) – for example, he would not allow himself to go for a casual drink after work when asked by an attractive colleague.

If you recognize yourself in the description of OCPD and you are a perfectionist, here is the good news. Changing your perfectionism will change your OCPD. There is such overlap between the two conditions that changing one will invariably have a positive impact on the other, and you do not need to do anything more. However, if you have the form of OCPD that is without perfectionism but is interfering with your life (like Jayne in the example above), then we recommend you discuss the issues with your GP and obtain a further referral for help.

If you have the sort of perfectionism we’ve been talking about, it is likely that at some point you have had feelings of being sad or down. This is not surprising, as if you spend a lot of time thinking that you have failed to meet your standards, then you are likely to end up feeling sad, low, helpless or inadequate. You may also be paralysed by indecision because of your attempts to ensure the best possible outcome.

To make the situation worse, it often happens that when you start to become lower in your mood or depressed, you lack motivation or drive to do things that you normally would do. As a result you may start to engage in some of the unhelpful behaviors we will discuss in more detail later in this chapter, such as procrastination or avoidance. This might then lead to your failing to meet your standards in consequence, which in turn might lead to an increase in depression and even more rumination (over-thinking) about how you have not met your standards. Take the case of Gemma as an example.

Gemma: An example of someone with perfectionism and depression

Gemma was a very bright student who studied hard in her undergraduate degree in literature so that she would be accepted into her Master’s year. While studying for her first degree she worked very long hours, spending a lot of time editing and rewriting essays, and always trying to write the perfect assignment so she could gain the best possible mark, which she often did. Despite the amount of time this took her, Gemma always managed to submit her assignments on time. When Gemma was accepted into her Master’s year and had to develop a proposal for the big research project which would determine her overall grade at the end of the year, she became very preoccupied with wanting to develop a perfect project. She felt the outcome was hugely important: if she did not write the perfect proposal, she believed, then she would not complete a good project, and if she did not do this then she might not be awarded her master’s degree, which had always been her most important goal. As a result, Gemma started procrastinating, putting off getting started on writing her proposal; when she tried to think of ideas she often found herself staring at a blank computer screen. Gemma started becoming tearful, thinking to herself, ‘I will never be able to develop a good project,’ and her mood began to plummet. This was despite meeting with her supervisor and discussing ideas together. Gemma started to sleep in late into the morning as she felt so tired, and then when she did get up she felt she had no motivation, and became tearful again, feeling guilty for not having made progress on her proposal. She became reclusive and stopped seeing her friends, and started to eat less as she did not feel hungry. This pattern went on for several weeks until she missed the deadline for her proposal.

We can see in Gemma’s case how perfectionism can lead to symptoms of depression, and how, as the more depressed she became, the more she ruminated on not meeting her standards. In this way it is easy to get stuck in a vicious cycle between perfectionism and depression.

While this book can certainly help you to overcome your perfectionism, it is important to note that if you have been feeling five or more of the symptoms in Box 2.4 every day for more than two weeks, then you may be depressed. In this case it would be useful for you to read Overcoming Depression by Paul Gilbert (see the ‘References and further reading’ section at the end of this book) or consult a mental health professional or doctor. If you can tackle your depression, this will give you a better chance of successfully working on your perfectionism. If you are feeling as though life is not worth living, you should seek professional help immediately from your GP or a mental health practitioner.

It is very common, particularly in women, for perfectionism to go hand in hand with eating difficulties. Perfectionism is a risk factor for eating difficulties, which means that if someone is a perfectionist, then he/she is more likely to develop an eating disorder than someone who is not. If you have eating difficulties, then one main area where your perfectionism is likely to be expressed is in the area of eating, your body shape, your weight and the need for control. Think back to the previous chapter when we were discussing areas of life where your perfectionism might be expressed: your shape and weight is another one of these areas. Take the example of Ifioma.

Ifioma: An example of someone with perfectionism and bulimia

Ifioma was an attractive young woman whose weight was in a healthy range. However, she felt very unhappy with the way she looked and thought she was fat and needed to lose weight so that she would be more attractive. Ifioma was always dieting as she felt she needed to lose ten pounds: this would bring her to her goal weight, which she thought would be perfect for her. Ifioma had many rules about her eating, including not eating more than 1,000 calories a day, not eating carbohydrates after lunchtime, and not eating a range of foods that she saw as fattening, which included chocolate, chips, sweets, butter, ice cream, cheese, biscuits, white bread, nuts and cakes. Ifioma would often be able to maintain ‘control’ over her eating during the day, and would eat very little for breakfast and lunch, but as the day continued she became hungrier and would belittle herself for this, thinking that she was already fat and telling herself to stop thinking about food. If Ifioma had a stressful day at work or an argument with her boyfriend then she would think she deserved just one treat to help her relax, and might eat a chocolate bar on the way home from work or her boyfriend’s house. This immediately triggered guilt in Ifioma for breaking her dietary rules, which would lead her to drive to the shops to buy some of the foods she avoided like ice cream and cakes. She would eat large quantities of these foods very quickly and had a sense of loss of control over her eating. After eating the food she would vomit to try to get rid of the calories. This left Ifioma feeling terrible, and afterwards she would berate herself for having broken her rules and become even more determined to restrict how much she ate the next day so that she could lose weight. This left Ifioma in a vicious cycle of striving to keep stringent dietary rules and then binge-eating and vomiting, which she did up to five times a week.

We can see how perfectionism is linked with Ifioma’s eating problems. She holds very rigid rules and demanding standards in regards to her weight and what and how she eats. When Ifioma breaks one of these rules, she feels that she has failed to meet her standards with regard to dieting and weight loss and she is then likely to binge. This is called ‘all or nothing thinking’, and we will discuss this in detail in Part Two (Section 7.5), as it is one of the most common aspects of perfectionism.

Ifioma had bulimia nervosa, a term which you have probably heard, along with the more familiar anorexia nervosa. The main difference between these eating difficulties is the actual weight of the person. The two problems have much in common and a checklist of symptoms can be seen in Box 2.5. If you recognize your own symptoms here, and particularly if your weight is low (Body Mass Index below 17.5)* or you are regularly vomiting, then you should consult a psychologist, other mental health professional or doctor as you might need more assistance; these eating difficulties can result in some serious physical effects. Alternatively, we recommend you read a self-help book such as Overcoming Bulimia Nervosa and Binge-Eating by P.J. Cooper or Overcoming Binge Eating by C.G. Fairburn (see the ‘References and further reading’ section at the end of this book).

If you are someone with perfectionism and other difficulties such as those described above, it is important to work out the relationship between them. For many people, it is possible to overcome the anxiety disorder, depression or eating problem without ever tackling the perfectionism and vice versa. For others, it may be that the perfectionism is contributing to the other difficulties. A useful idea developed by Christopher Fairburn, an internationally renowned expert on eating difficulties, is that of a house of cards.* If you want to bring down the house, you need to take out the main cards at the bottom that are supporting all the others. If you are someone whose perfectionism is contributing to your other difficulties, then tackling perfectionism will have a beneficial effect on the anxiety, depression or eating problem. It can also be useful to think of difficulties such as anxiety, depression and eating problems like the leaves of a weed and perfectionism as the root. If you pull at the root, and try to dislodge it from the ground, then the leaves are likely to start to wither.

Perfectionism is not only linked with anxiety, depression and eating difficulties; it can also cause behaviors which are unhelpful and cause problems. It’s easy to see, for example, how someone with perfectionism, trying continually to meet the demanding standards they set themselves, might start to use avoidance behaviors. Another of the most common behaviors that someone with perfectionism may use is procrastination. (We were going to tell you about that now but we think we’ll leave it for later . . .)

Seriously, though, these and other behaviors that can both result from perfectionism and keep it going are serious problems. We outline them here and are also discuss them in more depth in Chapter 4, where we look at the factors that keep perfectionism going. In general, what lies behind these unhelpful behaviors is the aim of trying to reduce what is perceived as poor performance.

Avoidance can be defined as something that is done by a person with an attempt to decrease or escape from anxiety about a particular situation.

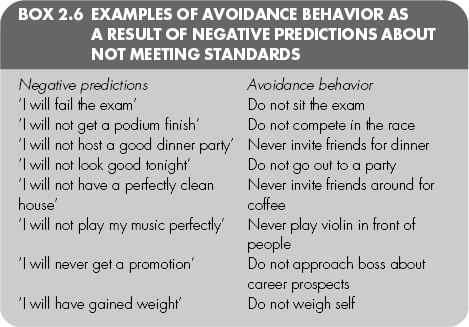

One of the most common reasons for avoidance in people who have perfectionism is a fear of failure. This is often based on negative predictions they make about a situation in which they feel under pressure to perform. Examples of negative predictions and the avoidance behavior that results can be seen in Box 2.6.

As you can see from Box 2.6, all these negative predictions are based on expecting the worst. Someone with perfectionism fears the worst possible outcome in their performance, and so, rather than risk being faced with that poor performance, chooses to avoid the possibility of it happening. While this is usually done with the aim of trying to avoid failure, in fact avoidance behavior can have the opposite effect, as it is likely to cause the person not to achieve in reality, the very thing they are afraid of and in fact trying to prevent. For example, if a student does not turn up to their exam, then they may indeed fail the unit they were studying. If a person engages in a lot of avoidance behavior through repeatedly avoiding testing their performance, they may never have a chance to find out that in fact their performance may be better than they fear. Avoidance also means you don’t get a chance to practice a task, learn from mistakes and continue to improve as a result.

Another motive for avoidance is that the task to be completed is so huge and awful, because of the high standards, need for thoroughness and ‘all or nothing thinking’, that it becomes unpleasant. If brushing your teeth takes you an hour, it becomes easier not to brush your teeth at all than to spend an hour brushing them. If tidying your child’s bedroom means you have to vacuum, clean behind the bed and clear out the cupboards, then again it is easier to allow the mess to mount up. Although many people with perfectionism live in immaculately kept homes, many also live in a mess because their goals for tidiness cannot be achieved, the task is too enormous and so they have given up altogether.

Procrastination – delaying a task until a later time – is very common among people with perfectionism. Procrastination often occurs because someone is so preoccupied with having to complete a task perfectly that they prefer to delay starting the task rather than face doing it less than perfectly – so it is in fact a kind of avoidance. As with other avoidance behaviors, it often stems from a fear of failure so intense that the person would rather put off starting a task than risk failing to perform it to the high standard they have set themselves.

Some of the common thoughts behind procrastination can be seen in Box 2.7. Ask yourself some of these questions to help detect whether they identify some of the thoughts that go through your mind when you procrastinate.

There are of course many other thoughts that may cause someone to procrastinate. The problem with procrastination in people with perfectionism is that this behavior is done with the aim of achieving a perfect performance, and yet, like the avoidance behaviors discussed above, it is likely to have the opposite effect. Continually delaying getting started on a task is likely to heighten anxiety to a degree where it may possibly impair performance once the task is started – or might mean that there is simply not enough time left to produce a good performance when the task is finally embarked on (for example, writing an assignment the night before it is due rather than giving oneself a week to write it). Procrastination can also lead to an accumulation of tasks, so that when one actually has to start doing something, the prospect of just starting can seem overwhelming. Take the case of Simon as an example.

Simon: An example of someone with perfectionism and procrastination

Simon had perfectionism about the cleanliness, order and appearance of his home. He thought that he had to have everything perfectly ordered, neat and tidy in every room of his house. However, Simon would often procrastinate and put off cleaning his house, as he would not know where to start. He would find himself moving from room to room, staring at untidy areas and thinking that he needed to organize each room perfectly and spend a long time cleaning each area in order for his house to be organized and look good. Simon often became overwhelmed with how much time it was going to take to clean and organize to a perfect standard, and so avoided starting at all. Gradually his house became more untidy and messy, which resulted in him feeling even more overwhelmed and procrastinating further.

You can see from the example of Simon that procrastination in fact has the opposite effect to that intended (guarding against poor performance), in that the more one procrastinates, the less likely one is to meet the required standards (in Simon’s case a perfectly clean and ordered house).

Many people with perfectionism repeatedly check how their performance is going (we refer to this as ‘performance checking behavior’). Box 2.8 sets out some examples of areas in which perfectionism is expressed and the type of performance checking behavior someone might do in that area.

We can see from the examples in Box 2.8 that performance checking behavior can take different forms. These include:

However, performance checking behaviors rarely result in a person feeling satisfied with their performance. Instead, it is likely that when we compare ourselves to others we think we have not performed as well as them. Often in perfectionism people choose unrealistic people to compare themselves to. For example, a novice athlete might compare himself to a professional, a woman might compare her body shape to that of a model in a fashion magazine, or a worker might compare his performance to that of his most senior colleague. As a result, comparing ourselves with others usually makes us feel worse about ourselves; this in turn makes us even more likely to compare our performance to that of others and keeps perfectionism going.

Seeking reassurance is also unlikely to result in a person feeling good about their performance. This is because people may not give a response that makes the person feel reassured, and even if they do, the feeling of reassurance is likely to be only fleeting, after which worry about performance usually kicks back even more strongly than before.

Many people develop habits that are designed to alleviate their symptoms of anxiety, depression, eating difficulties or perfectionism, only to find that unfortunately their strategies backfire and are counterproductive. For example, if someone suffers from anxiety attacks, they might always sit near an exit row in a cinema and take water and anxiety medication with them. This can be counterproductive as it increases the person’s thoughts about and preoccupation with danger, and they also don’t find out that they don’t have an anxiety attack if they sit elsewhere. Similarly, if someone has social anxiety, they might always keep their arms by their sides to guard against others noticing they are sweating, or never eat spicy food in case it results in their face becoming red and others thinking they are blushing due to anxiety. This behavior would be counterproductive because people may think this person is somewhat peculiar, thus responding in a way that increases the social anxiety. The basic problem with this kind of behavior is that the person never has a chance to find out that the very thing that they are worried about (e.g. others noticing blushing, having a panic attack in the cinema) might not occur – and that if it does, it will not be a catastrophe.

Counterproductive behavior in perfectionism covers things we do with regard to performance as a way of making us feel more at ease about performance, or even as a way of making up for what we see as a mistake. A common behavior in perfectionism is list-making. For example, you may make multiple lists of what you need to achieve for the week at work so that you don’t miss anything out, which would impair your performance. The purpose behind this behavior is to guard against the object of anxiety – in this case, falling short of the standard of perfect performance at work. Another example is organizing: for example, someone may ensure that several times a day at work they file each paper perfectly in the section where it belongs, and always try never to have loose papers on their desk, as a result of worrying about losing documents and being seen as incompetent. Both constant list-making and organizing can be counterproductive by consuming large amounts of time that would otherwise be spent on the tasks at hand. Working through the night to prepare for a presentation is another common behavior that can easily backfire, as it often leads to a worse performance the next day as a result of tiredness. Being over-thorough, trying to do too many things at once (multi-tasking) and rushing to avoid wasting time are all common counterproductive behaviors in perfectionism that are tackled in Part Two of this book.

* The criteria used to diagnose these problems can be found in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn: http://www.psych.org/MainMenu/Research/DSMIV.aspx.

* Body Mass Index is calculated by dividing your weight (in kilogrammes) by the square of your height (in metres).

* In his book Cognitive Behaviour Therapy and Eating Disorders: for details, see the ‘References and further reading’ section at the end of this book.