Over the course of the 1980s and 1990s there was considerable interest in developing and evaluating treatments for bulimia nervosa. This work proceeded in two main directions. First, a number of clinical researchers, mostly Americans, investigated the role of certain medicines, especially antidepressant drugs. Second, certain psychological treatments were developed, principally in Britain, and their effectiveness was assessed in clinical studies.

The research to date suggests that what we have learnt about the treatment of bulimia nervosa also applies to people with other binge-eating problems. However, not enough research has been done to be sure about this. The rest of this chapter focuses on what we do know from studies of the treatment of bulimia nervosa. More information on the treatment of general eating problems can be obtained from an excellent book by Christopher Fairburn, Overcoming Binge Eating (Guilford Press, New York, 1995).

The effectiveness of a number of antidepressant drugs in the treatment of bulimia nervosa has been assessed. These drugs come from three pharmacological groups: first, the monoamine oxidase inhibitors (such as phenelzine); second, the tricyclic antidepressants (such as imipramine, desipramine and amitriptyline); and third, the newer generation of anti depressants, the serotonin reuptake inhibitors (such as fluoxetine).

The findings from the studies of antidepressant treatment of bulimia nervosa do show that patients benefit. The frequency of binge-eating decreases by, on average, 50–60 per cent within a few weeks of starting a course of treatment. And there is a corresponding decrease in the frequency of vomiting and laxative-taking. In addition, preoccupation with food and eating decreases and mood improves.

These findings look encouraging. However, recent research has revealed some serious limitations to this form of treatment:

A further problem with treatment by medication is that many people with bulimia nervosa are reluctant to accept it. They want to tackle their eating problems on their own, without relying on a drug.

As it has come to be realized recently that antidepressant medication has only a limited impact on the longer-term outcome of bulimia nervosa, enthusiasm for this form of treatment has declined. It is particularly fortunate, therefore, that while the research into drug treatment has been taking place, similar work has been going on concerned with the effectiveness of psychological forms of treatment.

Cognitive behavior therapy The psychological treatment which has attracted most interest is a short-term psychotherapy, known as cognitive behavior therapy, specifically designed for patients with bulimia nervosa. It is based on the view, for which there is considerable support, that a key factor which prevents people with bulimia nervosa from spontaneously recovering is their extreme concern about shape and weight. The treatment aims to help people regain control over their eating and to moderate their concern about their shape and weight. It is usually conducted on a one-to-one basis with patients seen around 20 times over the course of approximately five months.

The effectiveness of cognitive behavior therapy in cases of bulimia nervosa has been studied in a number of careful clinical trials. The short-term results are very impressive, with reductions in the frequency of binge-eating of, on average, around 90 per cent being achieved. Following a course of this treatment, approximately two-thirds of people are no longer binge-eating. Vomiting and laxative-taking similarly decrease, and there is also a marked improvement in mood. Importantly, the tendency to diet is significantly reduced with this form of treatment. And patients’ concern about shape and weight becomes much less intense.

There are as yet few data on the longer-term impact of cognitive behavior therapy for bulimia nervosa. However, evidence is accumulating that the positive short-term benefits are well maintained: that is, the changes brought about by treatment do seem to be permanent.

Other treatments Many people who come for treatment of bulimia nervosa have had previous psychotherapy which has been unsuccessful. However, there are forms of psychological treatment other than cognitive behavior therapy which have been shown to be of some benefit to some patients with bulimia nervosa. None of these treatments is more effective than cognitive behavior therapy; most are less effective. They include behavior therapy, psycho-educational treatments, and focal psychotherapies (such as ‘interpersonal psychotherapy’ and ‘supportive-expressive therapy’).

Two variations of these different types of treatment are sometimes advocated. The first involves giving a psychological treatment to a group of patients collectively. This method of treatment appears to be somewhat less effective than individual therapy. Also, many people with eating disorders are too sensitive about their eating habits and their appearance to accept the idea of being treated together with other people. The second variation is a combination of a psychological treatment and an antidepressant drug. Clearly, given the positive benefits of a cognitive behavioral approach, such combination treatment is, by and large, unnecessary. However, some people who do not respond adequately to CBT may benefit from the addition of an antidepressant, however this remains to be demonstrated in systematic research.

People with bulimia nervosa and related problems differ in how much help they need to overcome their problems with eating. Some people will be able to recover completely on their own, with no outside help at all. Some will need to be admitted as inpatients to a specialist hospital unit.

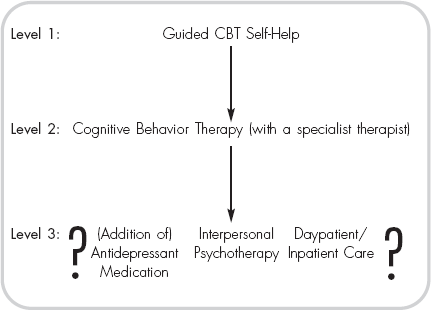

Figure 4 A stepped care program for the treatment of bulimia nervosa

Most, however, will need a degree of help somewhere in between these two extremes. One sensible suggestion which has been made is that clinical services for people with binge-eating problems should be organized in a ‘stepped’ fashion: that is, people would begin by receiving the lowest level of care and move up the system, progressively receiving more intensive levels of care if and when they needed to. However, opinions differ on precisely what form of treatment should be offered at each level. Figure 4 shows one account of the different options. While it is easy to be precise about the treatment offered at Levels 1 and 2, beyond that there is considerable uncertainty.

The first level is guided cognitive behavioral self-help. At this level people receive a self-help manual (Part Two of this book is just such a manual) which they use under the guidance of a helper. The evidence suggests that people using this manual entirely on their own do not do as well as those who use it with some external guidance. This is not to say that some people will not be able to make good progress using the manual on their own; however, on average, people using it with some guidance do better. The guidance necessary at this level of treatment could come from one of any number of sources: in Britain general practitioners (GPs) and the nurses who work with them are often best placed to provide this level of treatment. Social workers, psychiatric nurses and dieticians can also fulfil this role.

Most people who receive Level 1 treatment will experience benefit (see pages 74–7), and many will feel that they have made sufficient progress not to require further help. However, a few will not make any progress, and some will feel that they have not made sufficient progress. These people should receive the second level of treatment, namely cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). This should be provided on a one-to-one basis by a trained CBT therapist. This is the form of treatment on which most research has been carried out and for which there is the strongest evidence of benefit. However, again some people receiving this treatment may feel that they have made insufficient progress and that they require further help. This is the point at which there is uncertainty. There are several options available, including other forms of psychological treatment (in particular, one called ‘interpersonal psychotherapy’), medication (especially antidepressant drugs), and day patient or inpatient care. The decision in any particular case about which option to take is more likely to be based on what is available and acceptable, rather than on the evidence about which one is the most effective.