This chapter contains a brief account of how bulimia nervosa came to be recognized as a disorder, the prevalence of the condition, the criteria which have been specified for its diagnosis, and its relation to other eating disorders.

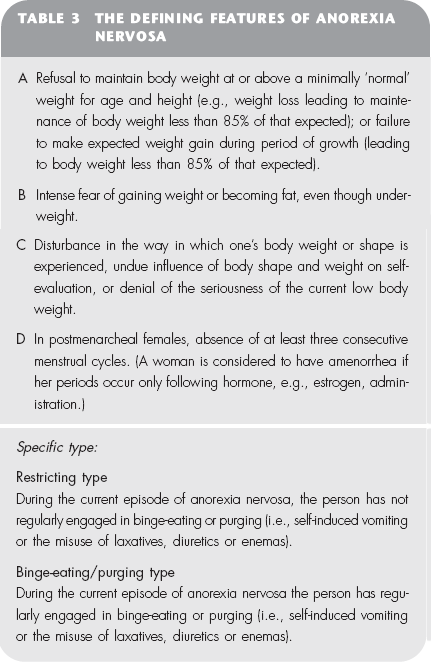

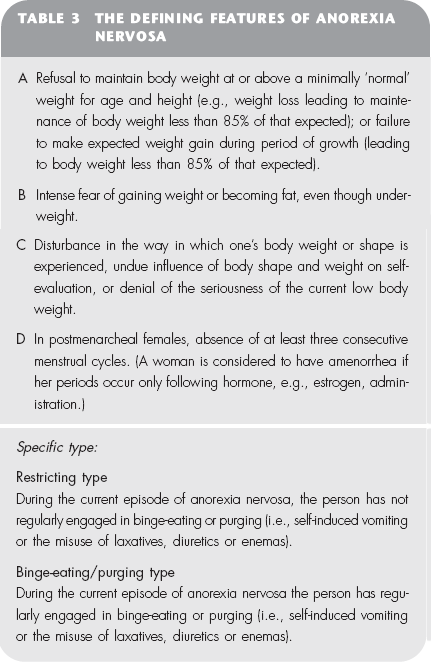

It has been recognized for a great many years that disorders of eating occur which are essentially psychological in nature. The most well known of these is anorexia nervosa. The first description of a patient with this disorder was provided as long ago as 1694 by the English physician Richard Morton. He described the condition of a young girl, ‘a skeleton clad only in skin’. The term ‘anorexia nervosa’ was introduced into the medical literature much later, in 1874, by Sir William Gull, Physician Extraordinary to Queen Victoria. There has, for a long time, been wide agreement about what the key features of anorexia nervosa are. Table 3 shows the definition provided in the diagnostic manual of the American Psychiatric Association.

Towards the end of the 1970s reports began to emerge of a new eating disorder in which the principal disturbance was episodes of uncontrolled overeating. People with this disorder were reported to resemble people with anorexia nervosa, except that they tended to be of ‘normal’ weight.

This newly recognized disorder was given a number of names (such as ‘bulimarexia’ and ‘the dietary chaos syndrome’), but the two terms which gained widest acceptance were ‘bulimia’ (used in America) and ‘bulimia nervosa’. The latter term was introduced by Professor Russell in a seminal paper which he published in 1979 in the psychiatric journal Psychological Medicine. In it he described the clinical condition of 30 patients suffering from ‘an ominous variant of anorexia nervosa’, a disorder he termed ‘bulimia nervosa’. Professor Russell’s paper is a remarkable exposition in which the features of a previously undescribed disorder are unfolded on the basis of the sensitive clinical observation of an experienced clinician. The paper is probably the most influential journal article to have been published in the field of eating disorders.

Professor Russell originally proposed the following three-part definition of the disorder bulimia nervosa:

1 powerful and intractable urges to overeat;

2 attempts to avoid the ‘fattening’ effects of food by inducing vomiting, abusing purgatives, or both; and

3 a morbid fear of fatness.

Over the course of the next few years, this definition was widely used by clinicians and researchers, especially in Britain and the Commonwealth, in identifying people with this disorder. Unfortunately, the criteria used to define the disorder ‘bulimia’, specified in 1980 by the American Psychiatric Association, were far broader than Professor Russell’s. This led to some confusion in the medical literature, particularly in relation to estimates of how widespread bulimia nervosa was (see below). However, agreement about the factors which define a case of bulimia nervosa has now been reached. Table 4 shows the latest formulation presented by the American Psychiatric Association. (The term ‘bulimia nervosa’ is now accepted on both sides of the Atlantic.)

Point A defines a binge as an episode of uncontrolled overeating. Point B lists a range of extreme methods used to compensate for overeating. Point C states that, for the disorder to be diagnosed, the disturbed eating habits should have been present for at least three months and have been occurring quite frequently. Point D states that a defining feature of the disorder is that self-evaluation is unduly influenced by body shape or weight. And point E states that, if all the four previous criteria have been met and the person also meets the criteria for a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa, then the latter diagnosis should take precedence. To aid future research into the disorder two sub-groups have been proposed, with a division between those who purge (vomit or take laxatives or diuretics) and those who do not.

Since the publication of Professor Russell’s 1979 paper and the appearance of the American criteria for bulimia in 1980, a number of studies have been conducted designed to determine the prevalence of bulimia or bulimia nervosa. Widely differing findings were reported. These related, in part, to the different definitions of the disorder being used. But they also related to the fact that key terms were not being adequately defined. For example, studies in which American college students completed questionnaires which asked if ‘they ever binged’ reported that the rate of binge-eating was as high as 70 per cent. Similar studies in Britain, however, which inquired whether people ever ‘experienced episodes of uncontrolled overeating’, produced a figure of around 20 per cent for young adult women. In fact, when people are interviewed in detail about their eating habits, and a strict definition of a binge is applied, the prevalence of binge-eating among young adult women is found to be between 5 and 10 per cent; and the prevalence of the full disorder of bulimia nervosa within this group is between 1 and 2 per cent.

Bulimia nervosa is rare among men.

The age at which bulimia nervosa begins is typically around 18 years, although most people who come for treatment do so in their early twenties. The disorder does occasionally arise in girls aged 13 and 14, but very rarely in girls any younger than this.

Over the past 30 years, bulimia nervosa appears to have become more common than previously. It is, however, not possible to be absolutely certain about this, because cases of this disorder may have existed before but gone undetected. Studies have shown that a history of having had bulimia nervosa is much more common among younger than older women, which does suggest that the disorder has become more common in recent years.* It is certainly the case that in countries where anorexia nervosa is found (i.e. Western and economically developed non-Western countries) there has been a dramatic rise in the number of people with bulimia nervosa coming for treatment. Indeed, bulimia nervosa is now one of the most common disorders encountered in outpatient psychiatric clinics.

Bulimia nervosa is closely related to anorexia nervosa. About a third of those with bulimia nervosa have had anorexia nervosa in the past; and many more have had some of the features of anorexia nervosa. The two disorders also have many symptoms in common. In particular, they share a particular kind of attitude towards body shape and weight (see point C of Table 3 and point D of Table 4). It is clear from the diagnostic criteria listed in Tables 3 and 4 that it is possible for someone to satisfy the main four criteria for bulimia nervosa and also fulfil the criteria for a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa. Indeed, nearly half those who suffer from anorexia nervosa periodically lose control over their eating and binge. In recent years it has become increasingly recognized that there are people who binge but do not take any steps to compensate for overeating. It has been proposed that they should be classed as having a third type of eating disorder, termed ‘binge-eating disorder’. The proposed definition of binge-eating disorder is shown in Table 5 opposite. Figure 5 shows how the three types of eating disorder relate to one another. The size of the circles roughly corresponds to the relative frequency with which each condition occurs. The overlapping of the circles shows which diagnosis takes priority. There is a general rule in psychiatry that if someone is suffering from two disorders, then the one that has the greater significance for treatment and outcome ‘trumps’ the other one, that is, it takes precedence in diagnosis and treatment. (See point E of Table 4.) According to this rule, a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa would trump one of bulimia nervosa, and a diagnosis of bulimia nervosa would trump one of binge-eating disorder.

Figure 5 The relationship between anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder.

* A New Zealand study published in the journal Psychological Medicine in 1990 found that whereas 4.5 per cent of 18–24-year-old women had at some time suffered from bulimia nervosa, among those aged 25–44 only 2.5 per cent had done so, and among those aged 45–64 only 0.4 per cent had done so.

Part One of this book has set out to provide a brief account of the nature of binge-eating and bulimia nervosa. If you have read thus far because you have problems with your eating, it should now be clear to you whether or not you have bulimia nervosa or some variation of this disorder. Similarly, if you have a friend or relative with bulimia nervosa, you should by now have an idea of the sorts of problems they experience with eating, and the kinds of effects these problems will be having on their life.

If you have problems controlling your eating, the question will now arise: What should you do about it? Chapter 5 has briefly outlined the range of treatments available for bulimia nervosa. You may conclude that your problems are not sufficiently serious to merit special attention and you may be happy to ignore them. Or you may recognize yourself in the descriptions given of people with bulimia nervosa and appreciate, if you had not done so already, that you need help. In this case you should certainly read Part Two of this book. This is a self-help manual for people with bulimia nervosa and variations of this disorder, and offers a practical guide to recovery. It has been shown in sound clinical research, carried out by a group of Australian clinicians, to lead to considerable clinical benefit in people with bulimia nervosa (see below).

If you have read Part One of this book because of concern for a friend or relative who has bulimia nervosa or a related binge-eating problem, you could also benefit from reading Part Two. It will help you to appreciate the considerable efforts which someone who binges has to make in order to recover. It will also help you to assist the progress of someone with the disorder who is attempting to use this book as a route to recovery.

THE AUSTRALIAN STUDY OF GUIDED SELF-HELP