In Chapter 6 on ‘The costs of changing’, we looked briefly at your confidence in your ability to change and how this can be low if you have been used to judging your worth according to your ability to meet your demanding and perhaps unrealistic standards. We call this a ‘rule for living’ that you have, and it goes something like this: ‘If I meet my standards then I am an acceptable person. If I do not meet my standards then I am no good as a person.’

When someone is a perfectionist, over time they demand higher and higher levels of performance from themselves to the point where they are trying to impose goals on themselves that are actually impossible to reach. In addition, over time the domains in which they seek to achieve can become narrower and narrower, and often they end up judging themselves almost entirely by whether they meet standards in one or two areas of their life (e.g. how they do at work, or their child’s performance at school). They feel worthy only when they are doing well in these areas of their life. Conversely, when things are not going well in these areas, the person will feel bad about themselves.

If this sounds familiar in your life, reflect on the disadvantages of living this way. One major disadvantage is that we are literally unable to control all the outcomes in our lives. Consider elite athletes who work hard to ensure high-level performance and think about how many times you have heard of injuries that have occurred for reasons outside their control interfering with their ability to attain their goals. If you judge your self-worth by the attainment of goals that are not always going to be in your control, then you ensure that your self-esteem will be a victim to circumstance. This will be especially true if you choose goals that are progressively more and more difficult and unrealistic and eventually unobtainable.

When seeking to weaken the link between your judgment of yourself as a person and your achievements, the aim is to base at least some of your self-worth on areas of life that can weather the storms that will rage around you, that are independent of achievement, and that are based on who you are and your intrinsic worth as a person.

A further disadvantage of judging your self-worth on achievement in a few areas of your life is that it encourages growth of the critical voice, which promotes strict and inflexible rules, as described in the earlier chapters. For example, you will notice an increase in such words as ‘must’ and ‘should’. Think back to some of your favorite teachers at school, the ones who showed a personal interest in you and wanted you to achieve or attain high standards. Did they help you achieve your goals by being autocratic and tyrannical and telling you what you ‘must’ and ‘should’ do? It is more probable that you didn’t much like the teachers who did that, and that they inspired rebellion or poorer self-esteem rather than gainful effort. Rather, the teachers who inspired you to try harder were likely to be encouraging in the face of effort rather than achievement, flexible in the goals they set with you, and understanding when these goals were not always met.

When seeking to weaken the link between your judgment of yourself as a person and your achievements, the aim is to avoid use of strict and inflexible rules and of ‘musts’ and ‘shoulds’, and instead encourage realistic and flexible goals.

Another disadvantage when you judge yourself on achievement in just a few areas of your life is the ‘putting all your eggs into one basket’ effect mentioned in Chapter 6. If your life is not going according to plan in these few life domains, then your sense of self-worth will suffer. We all judge ourselves to some extent on what we are achieving in our lives, and it is a wise insurance policy to spread these goals for achievement across many different areas – as well as work, study or artistic or sporting achievement, being a good friend, looking after important relationships, hobbies, your emotional and spiritual health, your community involvement, and so on.*

When seeking to weaken the link between your judgment of yourself as a person and your achievements, the aim is to base your self-evaluation on as many domains as possible in your life.

A final disadvantage linked with judging your self-worth by your achievements is that it encourages the growth of what is called ‘selective attention’. This was addressed in Section 7.6, where, as you will recall, we looked at how a person with perfectionism pays excessive attention to the times when they feel they have failed or not met their goals. The times when they have achieved something or done well will be dismissed, or given only a scant amount of attention. Some people even consider the goal must have been too easy or not worthwhile if they managed to achieve it. Again, if you imagine the teacher who spends most of their time pointing out their pupils’ faults, failings and limitations, you can see that this is likely to have a devastating impact on how you feel about yourself. Conversely, the teacher who spends as much time pointing out what you did well as on where you need to improve will be more likely to inspire better feelings about yourself as a person, which will lead to a steadier effort and better overall performance.

When seeking to weaken the link between your judgment of yourself as a person and your achievements, the aim is to notice equally what you do well and what can improve with the next opportunity.

When trying to understand how the rule ‘If I meet my standards then I am an acceptable person. If I do not meet my standards then I am no good as a person’ works specifically in your life, you will need to look for the ‘hot spots’ – the areas in your life that make you feel particularly bad when they are not going well, or that make you feel particularly good when they are going well.

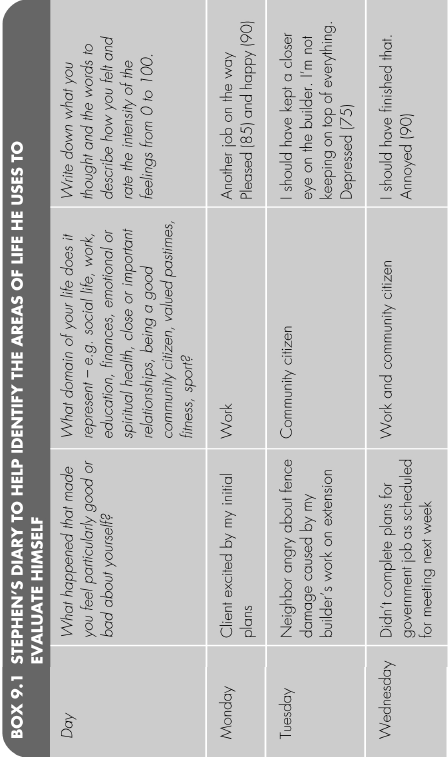

Consider the diary kept by Stephen (Box 9.1), a 35-year-old architect who has his own firm as well as working part-time and for much lower fees for the government on community projects he considers to be worthwhile. Stephen prides himself on always doing the right thing by other people, and delivering high performance at work. He lives with his girlfriend, and keeps fit by jogging four mornings a week. You can see from Stephen’s diary that the domains of work and being a good community citizen are the ones that influence the way he feels about himself as a person. He does not mention any impact of spending time with family or friends, or fitness. While he enjoys and appreciates these areas in his life, they do not consume much of his time and he does not consider any achievements in them as being particularly difficult or worthwhile; so they do not impact on how he feels about himself as a person. When he considered what was important to his self-evaluation, he thought that the key areas were work and his ethical standards for being a good member of the community. He summarized this in an ‘If . . . then . . .’ statement at the end of his week’s diary.

Use the diary below (Worksheet 9.1) over the next week to determine the areas of your life that you currently use to evaluate yourself and that determine how worthy you feel as a person. At the same time, be aware of the other areas of your life that don’t register on the scale in terms of influencing the feelings that you have about yourself. After keeping the diary over the week, see if you can come up with your rule, the ‘If . . . then . . .’ statement that equates your achievements with your self-worth.

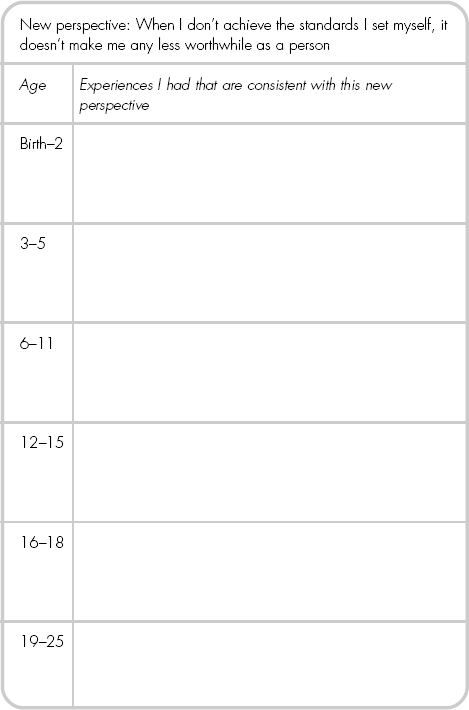

It is likely that perfectionism has become a stronger force in your life over time as you have grown older; from your current perspective it may well be difficult to remember a time in your life when perfectionism was not a dominating force. In trying to get back in touch with a life ‘before perfectionism’ it can be helpful to conduct a historical review of your life and test out your new perspective against what has actually occurred in your life. The example in Box 9.2 shows you how to do this, continuing on with the example of Stephen, and then you have an opportunity to do it for yourself in Worksheet 9.2.

It might make the message of the historical review stronger if you can find some relevant photos of the times or occasions that you refer to, and start your own scrapbook that illustrates this new rule. The scrapbook will remind you that the new rule has been operating in your life previously but has just been overlooked more recently.

Another way of reinforcing this new perspective is to write yourself a letter, taking the perspective of a ‘compassionate other’. This could be an abstract person, someone who doesn’t exist but has a compassionate nature; or it could be a real person whom you consider to be compassionate but whom you don’t know personally, like Mother Teresa or the Dalai Lama; or it could be a real person whom you do know and whom you consider to be compassionate. From this person’s perspective, write the letter to yourself, commenting on what the historical review showed about what makes you worthwhile as a person apart from your achievements or meeting your standards.

Another pathway to weakening the link between judging your worth as a person and your achievements is to adopt more flexible and realistic goals. Goals that are flexible do not include the words ‘should’ and ‘must’. An example of an inflexible goal for Stephen was: ‘I must always be on time for site meetings.’ An example of a more flexible goal for him is: ‘I will always try to be on time for site meetings but realize that I can’t control every eventuality all the time and may sometimes be late. I will make sure I have the client’s mobile phone number with me in case I need to call them to let them know that I will be late.’

Goals that are realistic are achievable after reasonable but not superhuman effort. Another of Stephen’s unrealistic goals looked something like this: ‘I must always complete the work that I have set for myself each day.’ This goal is unrealistic because it doesn’t take into account any unscheduled interruptions outside Stephen’s control, such as phone calls, unplanned visitors or issues arising with other jobs that are currently running. Also, Stephen may be setting himself too high a workload for each day, one that requires more than the hours in the working day to achieve.

One way of thinking through whether the goals you set yourself are achievable is to conduct a survey, as described in Section 7.3. You would survey people who you consider to have some achievements in their life and whom you admire, but who you also think have some balance in their lives and a good quality of life. Some of the questions you might ask them are: What types of goals do you set yourself each day? What happens when you don’t achieve them? How do you cope with that? With this information you can reconsider your own goals.

Stephen surveyed two colleagues of his who were architects and with whom he had gone through university. He knew that they had a good reputation and he admired much of the work they had done. After talking with them, he realized that although they set themselves ambitious goals for workload each day, their goals were a little less ambitious, and more obtainable, than his goals. Therefore they were less frustrated at the end of each day. In addition, they treated their goals as guidelines to help them keep the work moving, but not absolutes that had to be achieved that day. They also were more successful in allocating work to other people when they were under pressure, rather than keeping all the work to themselves and trying to spend even more time on trying to complete the work. Stephen found it helpful to get these perspectives and reconsidered some of his work practices in the light of this information.

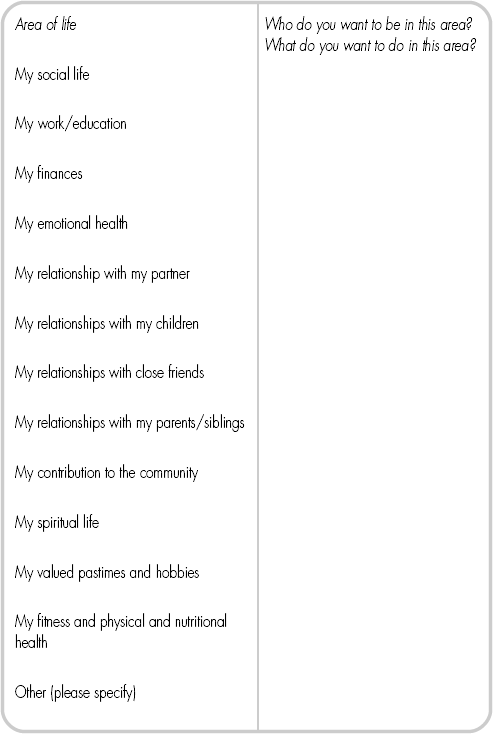

You started thinking about spreading out your self-evaluation more widely over different areas of life in Chapter 8. Now we can return to these ideas and take them forward another step. Look at Worksheet 9.3, which is similar to the chart you completed in Chapter 6 as Worksheet 6.4. Since last doing this exercise you have been considering many issues and practicing ways of standing up to perfectionism and the critical voice. Complete the exercise again and compare how if differs from what you did earlier. What new ideas or issues or goals have emerged?

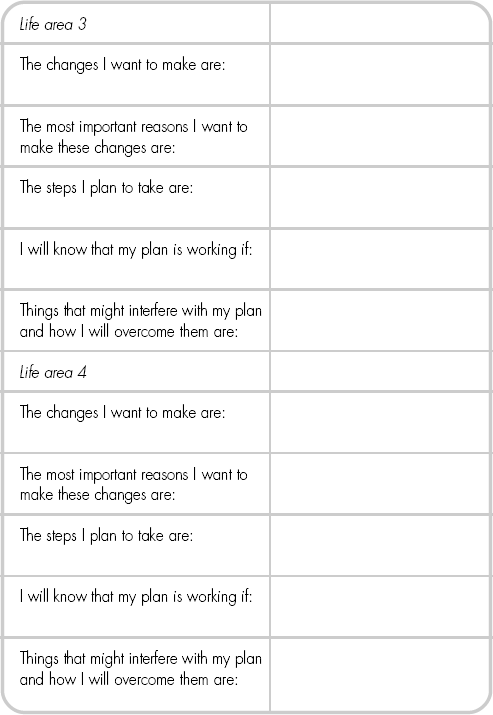

Now select four life areas that are different from those you identified at the beginning of this chapter that you currently use to evaluate your self-worth. Choose the four that appeal to you most and which you consider have the potential to contribute to, and expand, the way you evaluate yourself. Using Worksheet 9.4, set yourself some specific short-term goals (i.e. goals that can be achieved within a six-month period) in each of these four life areas. Some examples could include spending more time with certain people, or developing a pastime for enjoyment rather than achievement, or returning to hobbies that you have had in the past that have been neglected as you focused on achievement in fewer areas.

As you select the goals, keep in mind the issues discussed above with respect to choosing flexible and realistic goals, and avoid any use of ‘must’ or ‘should’. It may also be helpful to check with other people to see if they consider these goals attainable within six months. At this stage, choose small steps rather than large ones, as the idea is to start expanding some areas in your life, not to master a whole new area of life overnight.

The final step to consider in the process of weakening the link between judging your worth as a person and your achievements is to develop more balance in what you pay attention to as you go through your days. Perfectionists get used to paying attention to what they don’t do, or don’t achieve, or when they perform less well than they planned. However, they pay little attention to what they are doing well.

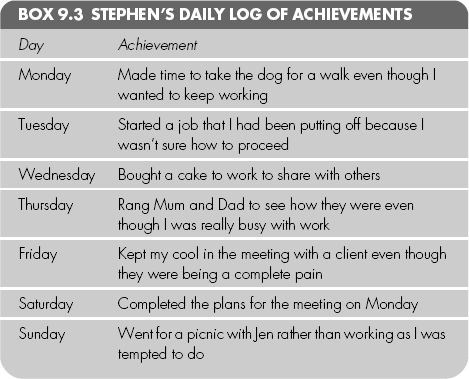

A simple way of retraining your attention is to keep a daily log in which you note down each day at least one thing that you have achieved or done on that day. Train yourself to look for the small achievements, in a broad range of areas, including the sorts of things you might normally dismiss. Box 9.3 shows an example from Stephen’s daily log.

Try keeping your own daily log, and remember the general principles:

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

* For more on this topic, see Overcoming Low Self-Esteem by Melanie Fennell: full details are in the ‘References and further reading’ section at the end of this book.