‘Always wanted never to have anything known about me’

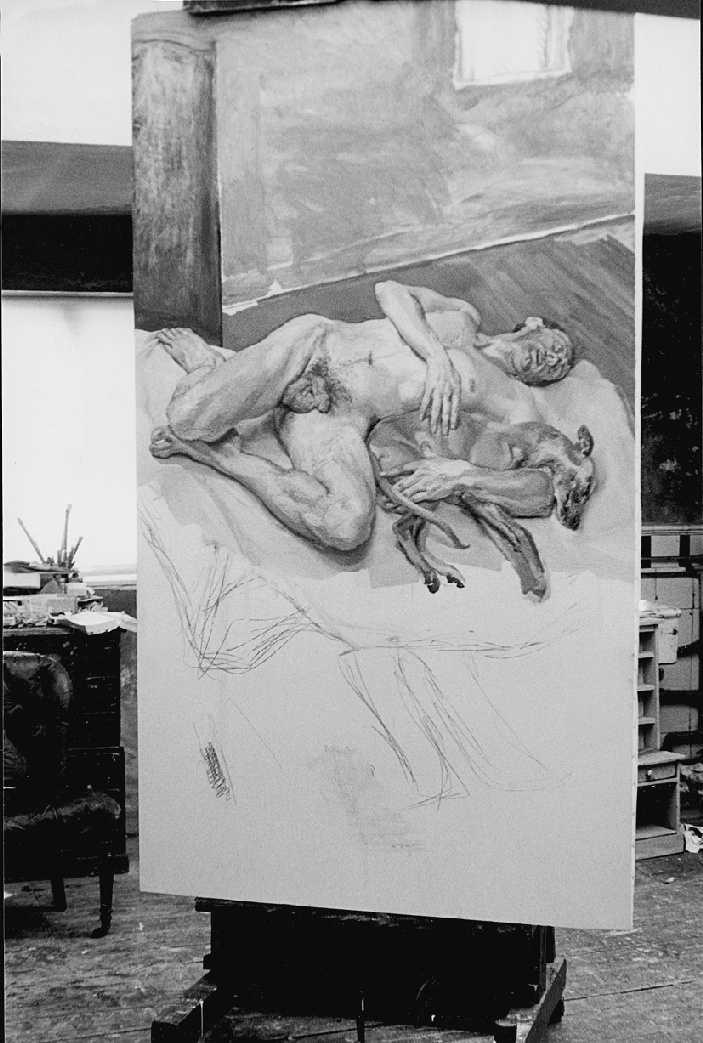

There were, as usual, several pictures on the go. The main one, on an easel directly under the skylight, was so far little more than eyes and chin, floorboards edging in, indications in charcoal of body on bed, a muzzle and smudge where Pluto the whippet would lie and a patch of white at the foot of the bed where a woman was to have stood. She had become intrusive, the painter had decided. A lesser distraction was needed. ‘Possibly something under the bed,’ he said.

While what was to become Sunny Morning – Eight Legs preoccupied Lucian Freud in daylight hours, others were worked on through evening sessions and into the night. Rose, one of his daughters, and her husband Mark were sitting for a double portrait, their heads distinct but as yet unrelated, the gap between them just beginning to be realised. ‘I’ve already put some air in here,’ was the comment. Another daughter, Ib, had been sitting with a book for a second daytime painting. The relationship of head to Proust had worked out well but more breathing space was needed and so the canvas had been extended. Proceeding as he did by accretion, form by form, Freud often found enlargement necessary. That way, ideas grew. The seams that zigzagged down all four sides of Ib Reading would soon be painted over, leaving scars visible only in a raking light.

Freud’s Holland Park studio: work in progress on Sunny Morning – Eight Legs, at a six-legged stage, 1997

Freud’s working methods were demanding while unassuming throughout. Presuming nothing save the presence of whoever or whatever he had felt like painting, he would go ahead with little or no preconception beyond the glimmerings of potential. Early on, as a beginner, there had been the buzz, the magic almost, of making imagined things substantial, making them convincing somehow. ‘In that way, once I got going, they led me on; I liked to have nothing there so that I felt they came from nowhere.’ Later he came to depend on engaging with what he actually saw, intuition reminding him, by the by, that a sitter’s outward appearance was ‘to do with what’s inside his head’.

No other painter in modern times has more straightforwardly made so much of the particular. He used to mock me for being obliged, he said, as an art critic to maintain ‘eternal vigilance’. Which of course was what in practice he demanded of himself. His was an intent alertness sustained hour by hour, week in week out. Painting had to be unremitting, never (in his words) ‘indulgent to the subject matter; I’m so conscious that that is a recipe for bad art’. He talked about perseverance as an instinct. Ruthlessness too, he assumed, but that went without saying. ‘I always thought that an artist’s life was the hardest life of all.’

Painting absorbs whatever affects the painter. Every consideration, emotional or otherwise, Freud believed, stretches a painting’s potential. ‘I don’t think there’s any kind of feeling you have to leave out.’ If the feeling wasn’t there, then ultimately the painting failed. Yet the feeling in a painting was necessarily filtered, distanced, objectified. He stressed the need to avoid ‘false feeling’ or gratuitous fervour. ‘I don’t want them to be sensational, but I want them to reveal some of the results of my concentration.’ His concentration over the years yielded paintings, drawings and etchings that fix insistently on what we are whoever we are, on the motif whatever it may be, getting a hold on the ingrained uncertainties that spice a life.

Freud liked unpredictability, particularly at the outset. ‘I try and vary the way I start. What I mean is, sometimes I put down a lot of paint but sometimes – say on a single figure – I start in a different place. Often I’ve started round the stomach and different parts. It’s to do with my horror of method, which may come of my having had such a rigorous method at the very beginning.’

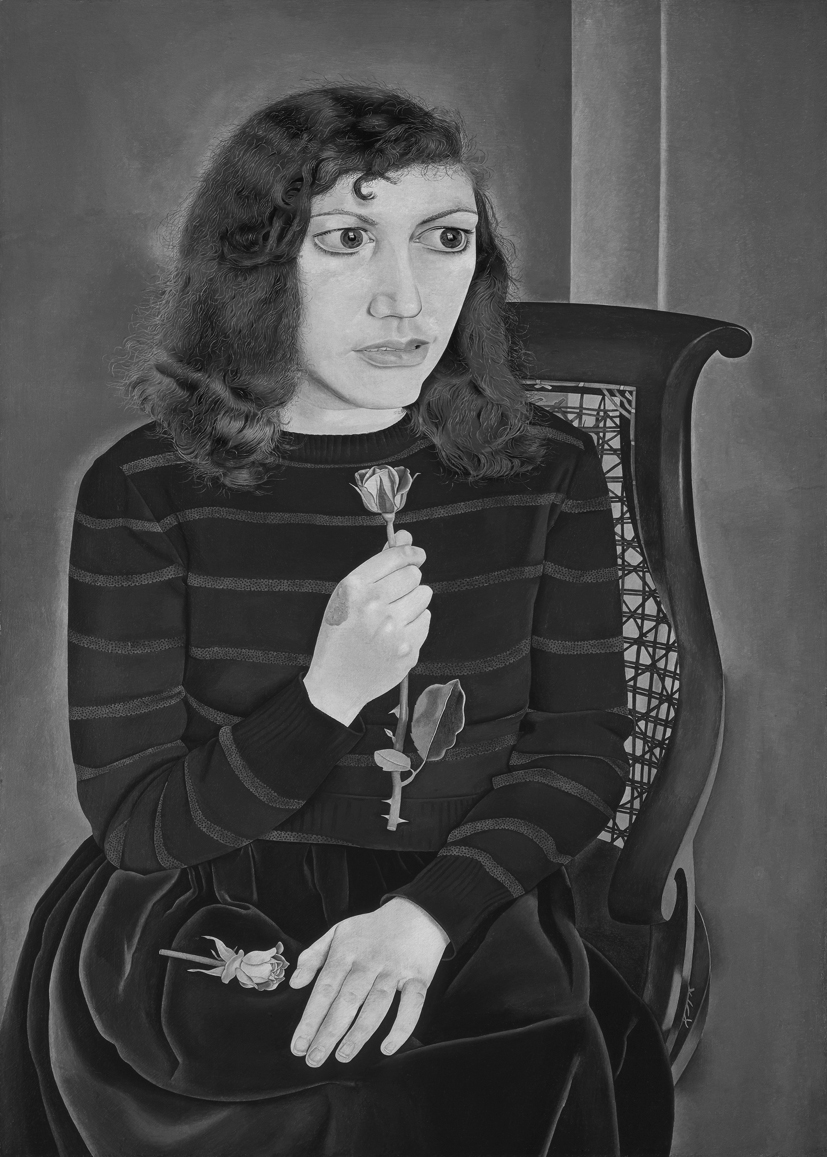

That method, conspicuously exhaustive, culminated in Girl with Roses (1947–8), considered by Freud his ‘first real picture’ and certainly one of the first to advance on a sizeable scale the notion of close attention as the essence of a relationship. The girl’s stare is subjected to that of the painter. She looks towards a window shown reflected in her eyes. Such detail may prompt metaphysical analogy (windows into the sitter’s soul), but it represents more the desire of an exacting young painter to make the image alert.

Girl with Roses, 1947–8

The sitter was Kitty Garman, a daughter of Jacob Epstein whose bust of her done three years previously represented her as a sort of naiad with a streaming head of hair. Epstein talked of ‘a trembling eagerness of life’ pulsing through such portrait sculpture: ‘Head, shoulders, body and hands, like music’. His future son-in-law, ‘the spiv Lucian Freud’, as he was to refer to him after the divorce, saw Kitty plain: wide eyes, braced shoulders, seated as rigidly as a playing-card queen. He had painted her a couple of times before, initially young and artless in a busman’s jacket and then holding a tabby kitten as though proffering a decanter, the relaxed limpness of the paws indicating a kindly grip on the neck of this namesake cum attribute.

Girl with Roses exemplifies wariness. It harks back to One Hundred Details from Pictures in the National Gallery, a selection made by the Gallery’s Director Kenneth Clark and published in 1938 in which, page after page, the black and white photogravure reproductions parade stimulating qualities: the poise of Holbein’s Christina of Denmark, the salon aplomb of Ingres’ Madame Moitessier, one of Freud’s favourite paintings and Clark’s most astute acquisition for the National Gallery in his time there. Leafing through, the detail that in sudden alacrity most vividly compares with Girl with Roses is the close-up of the tabby cat clinging to the chair-back in Hogarth’s The Graham Children: eyes enormous, thorny claws bared.

Thanks to Clark who fixed it for him, Freud used to have his paintings photographed by Mrs Wilson in the National Gallery photographic department and as Girl with Roses approached completion he began wondering how it would look in black and white. ‘I remember being so excited when I did the green stripes on the jersey. I put black dots on the green stripes because I thought if I put them in they’d come out. Like doing etching: knowing it won’t show on the plate but it will come out in the print.’ This peppering showed up well in the photograph. Reproduced opposite the tonal fug of a barmaid picture by Ruskin Spear, a blustery third-generation Sickert, in a 1951 Pelican book, Contemporary British Art, by Herbert Read (who, in a later edition, was to dub Freud ‘The Ingres of Existentialism’ and replace the Spear with a Burra), the painting looked radiantly distinctive. To the Greek poet Nanos Valaoritis, writing in the early 1950s, Kitty here was ‘petrified in a corner, at bay, like a frightened animal’.1

In keeping with the ‘things that are not made up’ that Freud admired in ancient Egyptian art, Girl with Roses exalts appearance. Here are individual fingernails and individual hairs, some with split ends, living relics as fully realised as the golden tresses of a Dürer. ‘I did the hair architecturally and moved it and watched it and then I did that thing, through working slowly, that I’ve often done, which is to change life to suit art.’

Daylight graces the painting, moulding the velvet skirt, glossing the lips, adding penumbra to the frizz of loose hairs around the head, streaking down the arm of the chair and silhouetting its torn cane-work. This chair, from a junk shop in a former chapel in the Harrow Road, near Delamere Terrace in Paddington where, since 1943, Freud had rented a flat, was peculiarly uncomfortable. ‘If you leant back the wrong way you snagged a nail. It’s useful in the picture.’ Equally useful is the congruity of forms, as calculated as any pin-up pose: flecked curls and curvy stripes; teeth and fingernails so alike; the nostril flare of the chair-back; the petal-shaped birthmark on the hand. The rose held up like a child’s buttercup thrust against the chin to test a taste for butter is halfway to being an emblem. Poetic rather than symbolic – the rose of Venus – it recalls the phrase of Rilke, ‘The rose of onlooking’, which Freud had seen in the September 1947 number of Poetry London. It and the other rose on her lap nuzzling her left hand are studiedly inanimate. ‘I suppose they are portraits,’ Freud said, by which he meant that they are specific, having been done from life. ‘They are not “let’s have a rose”, they are actual ones, those cheap bunches you got where most of them died but one or two survived; you don’t see them now: costermonger’s flowers, yellow and red ones, wired to keep them throttled. Very often they couldn’t get enough water so they just had asthma.’

Over time Girl with Roses has eclipsed the most famous seated figure in British art of the period, a figure in Hornton stone even more complacent than Ingres’ statuesque Mme Moitessier: Henry Moore’s Northampton Madonna, unveiled in 1944 in the Church of St Matthew, Northampton, by Kenneth Clark who remarked as he did so that it ‘may worry some simple people’. Moore, talking of ‘an austerity and nobility and some touch of grandeur’, had shrunk his Madonna’s head a little in the interests of monumentality. Freud did the opposite. For him there was the urge to accentuate. He had to achieve the looming look of a face that, as the expression goes, is all eyes. Knowing by heart, as he did, swathes of poetry of all kinds, there were phrases that bit into the memory and came to mind as he worked. Muttered, murmured, behind Girl with Roses, are lines he loved, Shakespeare’s pox on the rhetoric of ‘false compare’:

My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun;

Coral is far more red than her lips’ red:

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

I have seen roses damask’d, red and white,

But no such roses see I in her cheeks …

‘The fact of your life being your subject matter doesn’t in any way change the nature of art or artistic enterprise. And therefore it seems absolutely obvious, as well as convenient, to use as a subject what you are thinking and looking at all the time – the way your life goes.’