‘I love German poetry but I loathe the German language’

With a doleful shake of the head, during a platform discussion with me at the 1995 Edinburgh Festival relating to a ‘School of London’ exhibition, the critic David Sylvester declared Lucian Freud to be, in his view, ‘not a born painter’. Freud, he said, ‘had applied himself to the art of painting without ever convincing me that he was a painter’.1 Five days later in an article in the Guardian, written in response to a report of the discussion in The Times, he expanded on this notion of the inherent or incubated: ‘In reality he has become an outstanding painter without having been, I think, a painter by nature: he is a painter made, not born, made by a huge effort of will applied to the realisation of a highly personal and searching vision of the world.’2

Reading this, Freud laughed. Here was cliché rounding on cliché. Certainly he liked to think of himself as self-made. ‘I like the anarchic idea of coming from nowhere. But I think that’s probably because I had a very steady childhood.’ Anyone with Sigmund Freud as a grandfather could be all too readily assumed to have privileged access – by genetic imprint maybe – to a searching understanding of character and motivation, not to mention a predisposition to examine people on couches. The parallels are inviting: clinical analysis and portrait analysis, neuroses diagnosed and neuroses depicted. In reality however Lucian inherited only his grandfather’s fur-collared overcoat and a part share, with the other grandchildren, in the copyrights on his published works. True, the illustrious surname awaited him at birth. That may have provoked expectations. But the idea of anyone being born or not born an artist or indeed born a psychoanalyst was, he murmured, ridiculous. ‘It’s jargon. A twerp’s born. “A born idiot.” No, the only thing you can be born, actually, is a baby.’

Born in Berlin on 8 December 1922, the middle son of thirty-year-old Ernst Ludwig Freud, youngest son of Sigmund Freud, Lucian Michael Freud was named after his mother, Lucie Brasch, and Michael, the fighting archangel. His elder brother, Stefan Gabriel, had been born sixteen months before and the younger brother, Clemens Raphael, came sixteen months later. The 8th, number eight and multiples of eight were to become significant factors in gambling calculations throughout his life. As for the archangel names, Lucie Freud explained that they fitted in with her plan to have three children. She had been certain that she would have boys only.

Lucian considered himself isolated, outstandingly so, from the start. ‘My mother said that my first word was “alleine” which means “alone”. “Leave me alone”: I always liked being on my own, I was always terribly anxious there should be no competition.’ His mother, it emerged, had a special attitude to Lux, as both he and she were familiarly referred to. He was the born favourite. ‘She treated me in a way as an only child from very early on; it seemed unhealthy, in a way. I always longed to have a sister.’

Ernst Freud maintained an architect’s office in the large family apartment – tall, panelled rooms with chandeliers – in Regentenstrasse 23 in Lützow, an imposing district of Berlin near the Tiergarten, two streets away from where Mies van der Rohe’s Neue Nationalgalerie now stands. He had a partner and two assistants: ‘Mr Kurtz and Mr Augenfelt, who we called Grock (“Grockchen”) as he looked like Grock the clown who I’d seen at the circus.’ Lucian considered his father good at jokes but a bit distant. ‘I thought the one time I liked my father was when he used to walk me with my feet on his feet and he’d open his mouth and be a giant and take huge steps.’ Professionally speaking he was easy-going, so much so that he had to be bailed out on several occasions by his mother-in-law or cousins, the Mosses, when business ventures failed. He was happy, eager even, to represent the great Viennese Professor Freud at receptions in his honour. ‘My mother wasn’t: she felt it was wrong to be put in the position of going somewhere for his father rather than himself.

‘My father’s favourite musical instrument was the one-man band: bike, drum and trumpet. Grandfather too prided himself on being unmusical. In Vienna you have to have attitude.

‘He wasn’t the sort of architect who’d draw houses that weren’t built. Richard Neutra was an old friend of his from Vienna and Gropius he admired, and knew a little, but he was obviously not in the forefront. He did things very quietly and even though the style was quite radical he was not an innovator of the style, he was a user of the style.’ His buildings included a small cigarette factory, the Neue Villa in Dahlem, for Sigmund Freud’s friend Dr Hans Lampl, and a house overlooking a lake in Geltow near Potsdam for Dr Frank, Director of the Berlin Discont-Gesellschaft, a novel feature of which was a window, described in the Studio Year Book: Decorative Art 19343 as ‘a glass wall 20 feet long sliding down into the cellar, worked by weights and easily manipulated by hand’. He fitted out consulting rooms for psychoanalysts – couches calculatedly placed just so in relation to the analyst’s chair – and designed furniture: heavy shelving in African rosewood for his own study, and sofas that Lucian remembered as being ‘most inventive in ashwood and very severe’. In a Berlin of grand turn-of-the-century apartment blocks, the interiors that Ernst Freud produced were clear-cut expressions of modernity installed behind ponderous façades.

Frank Auerbach, who, many years later, was to become Freud’s closest painter friend and whose father was a lawyer, remembered the type of apartment that he and Lucian grew up in as being stiflingly well appointed: ‘The apartment. I don’t know what you’d call it. A sort of hexagonal hole with doors leading off it in various directions, my father’s office being one of the doors leading off. These flats were big and there were courtyards where people would beat carpets in the centre of the court. Ours was a Wilmersdorf flat. Tiergarten was Park Lane.’4 Evidently the Freuds, thanks to Brasch family money, were one step up from the Auerbachs.

Sigmund Freud with sons Martin and Ernst (seated left), 1916

In April 1922, Sigmund Freud wrote to Ernst for his thirtieth birthday: ‘You possess everything a man can want at your age, a loving wife, a splendid child, work, and friends.’ This was more than the usual good wishes. Earlier that year there had been (as Hans Lampl put it) ‘a brief period of alienation’ in his youngest son’s marriage about which he knew next to nothing, for disturbing news was generally kept from the Professor. However, according to his daughter Anna – a not altogether reliable source – he blamed his daughter-in-law for whatever upset or estrangement there may have been and lamented how few women know how to love their men. An admirer sarcastically referred to by Ernst Freud as ‘Schwäbisches Nachtigall’ (the Swabian Nightingale) was said to have addressed poems to her. Seventy years later Lucian Freud confirmed this. ‘He wrote these poems to my mother. Sonnets. But I don’t think she would have given my father any cause. She could never have had anything to hide; it wasn’t her way.’ As it was, the couple were reconciled, Lucian was born and the marriage thrived. ‘I’m sure they were happily married as they would go abroad on their own to Italy or Spain or Greece.’

Lucian Freud’s mother, Lucie Brasch, 1919

In later life both brothers, Clement and Stephen as they became known, took to letting it be known confidentially that, their mother having died meanwhile, the time had come to disclose that the Swabian Nightingale, Ernst Heilbrun, was, quite possibly, Lucian’s father. Setting aside the entertaining thought that if he didn’t happen to be descended from Sigmund then he could be relieved of the irritation of it being so often said that he had inherited the genes of psychoanalytical acumen, Lucian dismissed the guess as a brotherly slur. ‘My grandparents adored my mother. Both loved her and were terribly pleased that my father – gentle, quiet – had married such a talented and good woman. In some ways, considering what you read about Berlin then, they led a sheltered life.’

While Ernst Freud was known for easy-going optimism (though subject to migraines), Lucie Freud was admired for her seriousness, her beauty and vivacity and, moreover, for being a good housewife. ‘My mother’s classical scholarship – University of Munich – came in useful once, when they were on a boat and there was a priest on it and the only language they had in common was Latin.’ Ernst, being Austrian – the Berlin police picked him up once in the twenties as a suspect foreigner – lived by Viennese conventionality. ‘We had lunch on Sundays with our parents. Father required two vegetables for a main dish and he made coffee after the meal as men did that in Vienna: it was one of the links between Turkey and Vienna. The famous couch was Turkish.’

Home life was compartmented and secluded. First a nanny then a governess had charge of the boys. The barber came to the house, and the dentist. (‘Stephen said to me, “I forget: was it the dentist or the barber that you bit?”’) Round the corner, in Bendligstrasse – now Stauffenbergstrasse – were the Mosse cousins: Dr Mosse, his wife Gerda (Lucie’s sister) and their children, Jo who was a couple of years older than Lucian, Richard – ‘Wolf’ – a year younger, and Carola. The Mosses’ wealth derived from newspaper publishing, as did that of the Ullsteins, who lived next door to the Freuds. Gabriele Ullstein, a few months older than Lucian (whom she knew as Michael), was the granddaughter of Louis Ullstein, publisher of the Berliner Morgenpost and the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung whose Ullstein Printing House, on Ullstein Strasse, was one of the finest modern industrial buildings in Berlin. Looking back, Gabriele suspected that her mother rather kept her distance from Lucie Freud, uncomfortable with having so good-looking a neighbour. Arrangements however were made for the Freud boys to join Gabriele and others in an improvised kindergarten with use of the Ullstein sandpit.

Gabriele Ullstein and Lucian Freud c.1925

Every afternoon, Gabriele Ullstein remembered, nannies gathered in the Tiergarten with their charges and settled into cliques. Children with Misses looking after them were hived off from those with Mademoiselles or with Fräuleins. Superior broods had English nannies and governesses; Gabriele had Rose from Ipswich, then a Miss Penfold, then a Miss Parfitt, while the Freuds had a Bavarian to look after them. Lucian did not take to her. ‘Fräulein Per Lindemeyer (we called her Linde): I remember thinking there was something wrong about my mother coming up to the bedroom to get an affectionate goodnight when, just before, I’d been beaten by Linde the governess. Just bashes with her huge arm.’ Linde’s recollection of Lucian, decades later, he reported, was that he was ‘Very lively but not affectionate’.

‘When we went to Bavaria to stay in a chalet that the Ullsteins had, on the way down on the train to Munich, in the sleeping car, she fell out of the hammock.’

The Bavarian chalet had a balcony around it where every afternoon the children were made to sit on their potties. Silent concentration was the rule until one day, according to Gabriele, Lucian decided to play up, jerking himself along the landing on his potty like an eager jockey. He was, Gabriele felt, a born instigator. ‘Lucian had the authority of expecting to be obeyed.’ His memory of this went further. ‘I remember feeling very merry on the upstairs landing and wanting to go out looking for mushrooms and wild strawberries.’5 Let loose, they splashed around in a stream and competed to see who could get the most leeches on their legs.

Told at his first school to tie shoelaces in a particular way, he promised himself: ‘I’ll never tie them that way again.’

Misbehaviour always stimulated him. ‘We were walking with our nannies in the Tiergarten, with Michael and Paul, the sons of our doctor, Professor Dr Hamburger. There were beggars around, there were lots then, and there was a beggar with a flaming red beard and eyes and we rushed to get money from our nannies to put in his bag and tiptoed, terrified, up to him. But Paul, who was the youngest of us, toddled up and took all the money and put it in his pocket and I thought it terrifically funny, this amazing feat. When I got home I told my mother and she said it was wrong. But then when my Aunt Anna bought a farmhouse, with her friend Dorothy Burlingham, at Hochrotherd, the vendor was a beggar from the streets of Vienna: a prosperous beggar with considerable property, she was told.’ Paul Hamburger was to become, in London, Paul Hamlyn, publisher and philanthropist.

After lunch the boys were sent to their room for a rest and when the blinds were drawn Lucian would say, ‘Have I gone blind?’, knowing he’d get a reaction out of Stefan who couldn’t see the joke, ever.

Seventy years later Clement wrote about his mother’s favouritism. ‘When she came into the nursery she nodded to Stephen and me and sat down with Lucian and whispered. They had secrets. I did not realise for many years that this is not what good mothers do.’6 Lucian himself didn’t regard being his mother’s chosen one as advantageous. ‘It’s what my brothers resented; and so did I. A violent thing, really bad, was when, during a picnic, I picked, or took, some fruit. “Give it to your brothers,” my mother said, and she forcibly tried to take it from me and I wouldn’t let go. It was apricots, and I squashed them in my fist.’ He was to maintain that her reaction was inexplicably passionate, so much so that he never trusted her again.

Lucian used to say that always – or as far back as he could remember – he’d found his brothers unrewarding. ‘They were always together and I was always alone. On the Berlin tube Cle caught the outside of his hand in the outside of the escalator. Terrific screams. I remembered getting his hand out and thinking how odd: it was frightening but I thought just how odd. I was just looking at him screaming.’ A photograph taken in the street in 1928 shows them hand in hand. ‘The three of us in English clothes, tailored, and dark-suited sneering men staring at us pampered boys.’

Their mother read to all three but especially, he felt, to Lucian: ‘Schiller and Goethe ballads, Schiller’s “Der Handschuh” [The Glove], a ballad in which the hero drops into a cage to retrieve his lady’s glove, a cage with a lion, a tiger and two leopards who won’t fight: they spare him and he throws the glove in her face. And one about Frederick the Great, how he rode up and down in front of his troops in the battle and shouted “Gauner!” – Villains (No, that’s not the word. Spivs? Cheats?) – “Do you want to live for ever?” And a soldier answered, “Fritzen: not to betray for sixpence a day, this is enough.”’

Lucian was stirred by the rhythms if not the sentiments of Heimat – homesick – songs and he loved comic poems. The conceits in Christian Morgenstern’s Galgenlieder (Gallows Songs), printed in a heavy typeface on rough paper, appealed for their confounding logic: the notion of the gaps in a picket fence being used to build a house much to the fence’s annoyance; the clock with two pairs of hands, one pair advancing, the other retreating so as to tell the time both ways and, best of all, ‘Fisches Nachtgesang’ (Fish’s Night Song), spelt out wordlessly in typographic waters composed of hyphens and brackets. When he was seven he was given a ballad book with illustrations that ranged from Grünewald (‘marvellous’) to Adolph Menzel (‘thrones and lowly corners’); there were drawings he took a lifelong dislike to (‘Käthe Kollwitz, I’m sorry to say’) and drawings to wonder at, particularly Dürer’s study of his hollow-eyed mother and Das Grosse Rasenstuck (The Large Piece of Turf), his miraculously vivid clump of weeds.

Equally attractive were the picture books devised by a cousin, Tom Seidmann-Freud (born Martha Gertrude, daughter of Ernst’s elder sister Martha Freud), who died in 1930 aged thirty-seven, shortly after the suicide of her husband Jankel Seidmann. Her books were made to be tweaked and fingered and coloured in. ‘Things you could pull and things disappeared and red and blue paper where, if you passed them across the drawings, people disappeared. I loved the way they were drawn.’ Das Wunderhaus (The Wonder House) and Die Fischreise (The Fish Journey) were perked up with trim little outline drawings of captivated youngsters, amazing flowers, whippety rabbits and suchlike. The even more succinct Hurra, Wir Lesen! Hurra, Wir Schreiben! (Hurrah, We’re Reading! Hurrah, We’re Writing!) (1930) and Hurra, Wir Rechnen! (Hurrah, We’re Counting!) (1931) had squirrels, storks, cats, frogs and children of all nations and races prompting first steps in reading and arithmetic.

Tom Seidmann-Freud: Hurra, Wir Lesen!

Freud’s earliest drawings, treasured by his mother, displayed similar idiosyncrasies, demonstrating what Grandfather Freud characterised as ‘strahlende Intelligenz’, the radiant intelligence of children. There were upbeat goblins, skeins of chimney smoke intertwining over rooftops and rhythmic flights of fancy: five eager-beaked birds in a five-fingered tree all straining in one direction, readied to be up and away.

Birds in Tree, c.1930

Though Grandfather Freud lived in Vienna, he came to Berlin every so often for cancer treatment and to be fitted with what he described as ‘the very model of a necessary evil’: a prosthetic palate to separate his ravaged oral and nasal cavities.

‘My first meeting with him was when he was in Berlin, by the lake where he was having therapy or rest. When he walked he was quite bent in a way people are who sit a lot. He was frail.’ His grandfather, he discovered, was a mushroom hunter with biological skills (he could sex eels) and a taste for Morgenstern’s catchy poetry. He also knew all about Max und Moritz, Wilhelm Busch’s comic-strip urchins; indeed, the very first time he met him, he acted like a Busch grotesque. ‘He snapped his false teeth at me and my mother was upset.’ Also, inspiringly, he gave him reproductions of Brueghel’s Seasons from the Kunsthistorisches Museum. Of these Lucian particularly liked Hunters in the Snow because of the skating, and The Return of the Herd with the cattle blundering down the lane. ‘There are no bottoms like them.’ Another time he brought The Arabian Nights illustrated by Edmund Dulac (‘lovely fat books with what seemed to me pretty good watercolours. I don’t know if I’d like them now’) and a two-volume Grimms’ Fairy Tales. Lucian made a set of illustrations for ‘Snow White’ foregrounding the dwarfs: a dozen or so drawings in a concertina strip joined up with stamp hinges. This he presented to Linde.

‘A child’s emotional impulses are intensely and inexhaustibly deep to a degree quite other than those of an adult; only religious ecstasy can bring them back,’ wrote Professor Freud.7 He once listed Kipling’s The Jungle Book among his ten favourite works of literature. Its correlation of childish impulse and animal instinct must have appealed, and the flavour of myth. Lucian’s prospects as a Mowgli of the Tiergarten were not good, but he had a golden salamander and there were cats that he used to ‘love and torture’ and an English greyhound called Billy.

Lucian’s maternal grandmother Eliza Brasch, known to them as Omi, owned an estate at Cottbus near the Polish border. ‘She was this rich widow and I think the reason my father and mother set up in Berlin was because my grandmother helped them economically.’ Lucie Freud did not get on with her mother. ‘She hated her. It was unreasonable. She and her sisters had had a French governess, whom all adored, and their affection went to her and so my grandmother couldn’t forgive my mother for not having her affection. Here was my easy-going, bridge-playing grandmother who saw this and said she’d give the governess the sack, and my mother and her sisters – aged ten, eleven – said they would kill themselves if she did. So she kept her.’

Decades later Lucian’s eldest daughter Annie was impressed by her grandmother Lucie’s concern for her emotional wellbeing. ‘She believed that a child ought always to approve of itself and that there should be no such thing as clandestine. For example, when a child began to get obsessed with pooh, shitting, words, things like that, she would work out a little system of things – rhymes for what I did so that I could get them out of my system, so that I could not as it were get infected with all this dirty talk.

‘It was tyrannical but it was also fantastically secure. My hand in hers. One of the main things about being a child is your physical relationship with the people who love you or are meant to love you. And her hand was absolutely the softest and most enveloping thing and she would always hold my hand if I went out. If I had a story to tell about my toy rabbit she would take this story, there’d be no irony in the way she’d respond; if I decided my toy rabbit was going to get married she would get her dressmaker to make her a wedding dress. It was completely selfless, this enveloping love for me.’8

Grandfather Brasch, who died before Lucian was born, had been a grain merchant. He had acquired the Cottbus estate in lieu of debt. ‘He’d behaved nobly in the war. Asked by the Kaiser to supply grain he said he would, but not on a profiteering basis. I asked my mother, “Everything you say about your father not profiteering: if so, why take the property?” She said that he didn’t want to accept, but my grandmother was so keen on it that he did.’

The house, Gross Gaglow, built around 1902, was big and ugly, with high windows and a stable full of horses. The boys spent holidays there. ‘We were met at the station in marvellous coaches: they had different coaches for different occasions. The stables caught fire once: nothing to do with me except that it kindled my love of fire. It was very feudal there and the village related to the house.’ Once, when all three were ill, children at the village school were let out so that they could come up to the house and entertain them.

‘My mother hated the estate because, with her classical education and love of the ancient world, she felt it was sort of sybaritic. I loved it there. There was, for instance, an ice-bank so you could have ice any time in the summer: an ice mountain with a straw cap over it. That seemed incredibly luxurious.

‘Motor cars were few; but there was a friend of my grandfather’s called Lampl and I remember driving over the border with him and being so excited at going over there, probably into Czechoslovakia.’ Czechoslovakia (a recently created country: product of the Peace of Versailles) or wherever: countries were just names on the mixed packets of postage stamps that he used to send off for on approval.

His grandmother’s Berlin apartment, in Hardenbergstrasse, Charlottenburg, was impressive but off-putting. ‘The drawing room was formal, dark, with a huge tasselled lamp over the table, incredibly comfortable and luxurious. Palm trees about a lot, carpets on the tables: a sort of palm court feeling, like the Ritz.’ The bedroom had a polar-bear rug and ivory objects, and statuettes of Napoleon Bonaparte. ‘There was a great fashion for Napoleoneana. Rather like people now having things of Hitler. My mother thought my grandmother was terribly vulgar as she had bridge parties where they drank beer.’

His grandmother used to take him to the Charlottenburg museums and the Neues Museum on Berlin’s Museum Island. The painted bust of Nefertiti – recently made public and astonishingly immediate with its serene authority – impressed him more than the Rembrandts, which struck him as ‘brown and disgusting’.

The Brasch relatives were familiar to Lucian, unlike the Freuds in Vienna; they were also wealthier and, in some cases, more memorable. ‘My mother was one of three sisters and there was an elder brother, Erwin Brasch, whom I never met. He was in the war and was an officer and was on patrol when he suddenly realised he had been deserted in this sinister wood by his platoon. He was captured, thrown into prison and then sent to Africa. In the train he went to the loo, broke the window and tried to jump out, but they caught him by his legs. After having been the only son from a wealthy family, trained in the law, when he came back from the war he was really troubled and restless and wandered around the streets and fell in with a religious lot and married a woman from the streets who had been a whore, supposedly. The marriage was a private marriage conducted in my grandparents’ flat and, not long after it, my uncle’s wife cursed my grandfather and said that she wouldn’t have children, or couldn’t have children, because he disapproved of the marriage. He was terribly upset by this and died.

‘My uncle became a Catholic missionary and went with his wife to the Mount of Olives where they built a house and he became manager of Barclay’s Bank – I always say Olive Branch – and was very friendly with the Arabs and everyone liked him, and one night, coming home from having dinner with the Arabs in the hills, he was murdered by the Irgun, probably mistaking him for a Jew, which he was, but he was a passionate Christian. That was in the thirties, not long before the war.

‘My mother’s younger sister, Gerda, whom she adored and would do anything for, was married to a children’s doctor called Carl Mosse. I had an extra toe on my small toe, which he removed when I was two or three. I said to my mother, “How dare you,” but she said she thought I would have had such trouble later if it hadn’t been taken off. Anyway, he left my aunt, went to China and lived at 101 Bubbling Well Road in Shanghai, where I used to write to him, just to be able to write the address on the envelope. He sent a backscratcher as “a present from”. I thought of him in a friendly way but my mother didn’t. “He’s awfully vulgar,” she said. A funny thing: when Uncle Carl went to China his three children turned into orientals: Jo, who I liked, looked like a Pekinese. The elder sister married a horrible art dealer, Hans Calmann, a banker who when he came to London became an art dealer because that was his passion. He had a gallery in St James’s Place; she died in Hamburg. I used to stay with them sometimes in their very grand eighteenth-century house in Hamburg. I remember a spiral staircase with old maps, with ships on the maps.’

Hanging in the Freuds’ apartment, besides Lucian’s Brueghel reproductions and the Dürers, was a framed watercolour of oak trees by Ernst Freud who had studied art during his architectural training in Munich and remained partial to Klimt. His few surviving drawings – which Freud turned up when he went through his mother’s belongings after his father died – date from around 1913 and feature villas in diamantine Alps overlooking Italian lakes. Secessionist in spirit, carefully so, they do not suggest that he ever entertained any strong ambition to become a painter. Ernst once told his father, according to the Wolf Man, Freud’s famous patient, that it would be foolish for anyone such as him, of moderate means, to take up art. He did however have in his library George Grosz’s graphic portfolio Ecce Homo. Lucian admired the yellow bindings of his edition of Conrad and realised, later on, that he had quite a daring taste in modern literature. ‘A great deal of Rilke – my mother adored his work – and a first edition – the only edition then – of Kafka’s Metamorphosis.’ It puzzled him rather that his father had such books. ‘But then, lots of people have lively moments when students.’

For their entertainment, once they were old enough, a projectionist was hired to show films in the apartment. ‘The first film I ever saw was actually an English film [in fact American] called Bring ’Em Back Alive, about wild animals.’ Made in 1932 the film featured a baby elephant being bottle-fed and fights between python and crocodile and python and tiger. ‘In Germany children weren’t allowed to see films with love interest – a kiss meant love interest – and the most marginal, near-dirty film some children were allowed to see was a Charlie Chaplin film, that one with the famous dance with the buns: The Gold Rush. It had a kiss in. That was the dirtiest film I saw. But Felix the Cat was all right.’

Being Jewish, distinctively so, part of the Jewish 4 per cent of Berliners, had not impinged until then. The family never went to synagogue and there was no religious observance. ‘I was not a practising Jew but perhaps conscious of being a little non-Austrian. Like all proper Jews I’m not interested in religion.’ Years later he agreed joyfully with something that Isaiah Berlin said to him, quoting Heine: ‘The Jewish religion is not a religion, it’s a disaster.’ Lucie Freud did suggest once, perfunctorily, that he should try shul.‘Why?’ he asked.

‘It’s to do with your ancestry.’

‘So I went for one lesson or maybe two but I thought the rabbi smelt, so I said that I wouldn’t go any more. Mother was completely agnostic.’

Ernst Freud had Zionist inclinations, and possibly a pious streak. ‘If it hadn’t been for the agnostic tradition of my grandfather, my father would have been quite talmudic, I think, because he liked the ritual and the curious sort of scholarship. He had all his volumes of the Talmud bound in red.’ But Sigmund Freud’s unbelief was persuasive. ‘His final kick at the Talmud was that book he published here in England: Moses and Monotheism, about Moses being an Egyptian floating down the river. An outrageous book.’

The family could not but be conscious of their Jewishness, however, in that it was increasingly held against them and used against them. Sneers hardened into threats. ‘I used to collect cigarette cards: Abdulla cigarette cards had profiles of movie stars. Stephen and I got my brother Cle to ask people for them, to go into cafés where Nazis went and say, “Heil Hitler, have you got cigarette cards, please?” And some would say: “Yes, all right. So long as you don’t give them to any little Jewish boys.”’

The Freud brothers hand in hand: Stefan, Clemens and Lucian (right), Berlin, 1927

Art appreciation was something to be encouraged. And art as an expression of growing awareness: what better indication could one have of a child’s personal development? Lucie Freud kept the drawings sent to her by the boys in their letters from Hiddensee, the island off Germany’s Baltic coast where they spent summers, June to September, often while their parents stayed in Berlin or went off on their own leaving them with the governess.

‘Hiddensee lay stretched out from north to south, long and narrow like a lizard lying in the sun,’ Elizabeth von Arnim wrote in The Adventures of Elizabeth in Rügen, published in 1904. The island was the perfect playground. Anna Freud rhapsodised over it. ‘A combination of everything beautiful in one small patch and with air and wind and sun and freedom.’9 Sigmund Freud, who stayed there once, in 1930, in the lighthouse hotel, but left after a couple of days when his heart condition played up, said that it was a Gesundheitsparadies (health paradise) for the children, if not for him. The attractions – sea, sand and away from it all – were also its drawbacks. Einstein went to Hiddensee, as did Franz Kafka, Billy Wilder, Bertolt Brecht, Hans Fallada, Ernst Barlach, George Grosz, Erich Kästner, Rainer Rilke, Thomas Mann and Walter Trier, the cartoonist and illustrator, who drew carefree figures bouncing around its dunes and hills. At least one of these now celebrated cultural figures, Edgar Wind the art historian, once called on the Freuds. Little Lucian, according to his mother, said to him, ‘Wind: did you blow in through the window?’

‘Hiddensee was between Germany and Denmark, opposite Rügen, where Isherwood and Spender went. It was a long strip of an island in the shape of a seahorse with some hills at the far end where there were some rather grand houses, castellated places, where the Nazis had a castle, and then a narrow middle part, which you could walk across in ten minutes, with the middle village, where we had a house, with a baker’s next door where Linde the governess used to take the plum cake she’d made to be baked, and then a far-off village, Neuendorf, where people practised free love.’ Lucian’s mother tried explaining to him what they did. ‘These are odd people,’ she said.

The Freuds’ cottage in the village of Vitte was steep-roofed and semi-detached; the other half belonged to a fisherman and his family called Kollwitz. ‘They spoke Mundart [dialect] Plattdeutsch. The daughter, Irma, was ten, pretty and very strong and had a huge German plait and she would sing, “Dengst du den, dengst du den …”, a song that translated “Do you really think, you Berlin weed, that I like you …?” A large pear tree stood by the house, which I had a lot of life in.’ He drew himself as an elfin nipper standing between house and pear tree with an airship – the Graf Zeppelin – passing overhead.

Hiddensee House with Artist, Pear Tree and Zeppelin, c.1930

Lucie Freud kept a record of the holiday summers in a series of photo albums, a dozen altogether, mostly one snapshot per page for the usual arrival, the walk to the house along the track between flat pastures where horses grazed, sailing expeditions, picnics behind a wicker windbreak with buckets and spades and model boats, Billy the greyhound in his muzzle, Ernst in holiday trousers, the three boys lolling on a swing seat, Lucian looking out to sea, Lucian with a retinue of admiring little girls. One summer their Mosse cousins joined them and they played diabolo, at which Lucian showed off his dexterity, and hide and seek in the pine trees, where they were thrilled to be trespassing.

Lucian with kitten, c.1928

Mishaps were a further stimulus. ‘I was cycling in the middle village on a fixed pedal cycle and obviously it couldn’t brake, so I came down from higher ground to the harbour whizzing pedals at speed and threw myself off the bike, as I couldn’t swim. My mother, in trousers, and her friend Tanya were standing there as I crashed on to the pebbles and covered myself in cuts and bruises.’ And then there was school, obligatory when the stay on Hiddensee was prolonged beyond high summer. ‘Huge classes of village boys. We were asked “How long did the Thirty Years War last?” and I was the only boy who could answer. The schoolmaster was sweet on Linde.’

Lucian sent drawings to his mother with covering letters in spiky German script. ‘This is good, take care of it,’ he wrote on one of them. Looking through them sixty years later, still smarting at being explained by David Sylvester, he remarked that, if not a ‘born artist’, certainly he had been a lively beginner, drawing the lighthouse on the point and the clumsy great ferries Swanti and Caprivi, seabirds aloft and bright flowers shoved in jugs. What better subject than what they’d been enjoying, a boat trip to Denmark or jelly for tea?

One afternoon, while they were playing bowls, a cart filled with drunks came lurching down the grass strip that ran through the village. ‘We moved out of the way, to let it pass, and my mother was obviously very worried when they slowed up and leered at her. One of them, a red-faced, huge young man, said – looking at Stephen, who hadn’t taken in what was happening – “Mildly Jewish-looking youth, I would say,” and my mother went scarlet. I remember that: the strange atmosphere. The whole thing was very very odd.

‘There used to be thunderstorms in the hills on Hiddensee. They were trapped there and couldn’t get away and got stuck, people said. I liked that idea.’

Unlike their Mosse cousins, the Freuds were sent to state schools. Lucian began at the Volksschule near by in the Derfflingerstrasse in 1931 when he was eight. He went on his own. Choosing a smallish street for the purpose, he tried his own version of Russian roulette, standing on the pavement, eyes closed, counting to ten and running across, eyes still shut. ‘To test my fate. Until finally hit. I was hit by a car and thrown up in the air and as I came down I was hit again as the car stopped. I lay there and a crowd formed and wanted to lynch the poor driver. As I went through the air I wetted myself, as you do when you’re dead. The crowd said we must have your address, so I pretended to be deaf and dumb and limped away. In the bath the governess said, “What happened?” I’d been hit on the thighs and was all blue. I was running when the car hit me and went up, perfectly relaxed I suppose. Well, I proved that I was not indestructible. Mother never found out.

‘Derfflingerstrasse was very mixed, middle class and working class. I had a friend called Schucki – Schuckmeier or something, very plebeian – who was my friend, at school only. It was slightly unthinkable to bring a street boy home.

‘“What do you do at Christmas?” he asked me. “We have half Christmas and half Chanukah. What do you do?” “My brothers and sisters, father and mother and grandparents, we eat and drink until we fall under the table,” he said. I was mad on skating and, looking for danger in the Tiergarten, I skated under a bridge, got through but, where the ice was thin, went into the water. A man, very thin and dressed in black – Berlin poor – pulled me out and he turned out to be Schucki’s father. After that I was allowed to take Schucki home.

As circumstances worsened, economic disaster triggering extreme reactions, the ten-year-old Lucian became aware gradually that politics could affect him. ‘There was a socially conscious teacher who was obviously very fond of my mother, and he was worried about the situation in Germany and he said in class, “Any of the boys whose parents are unemployed, will you put your hands up?” I’d heard a lot of talk at home (my father was getting less and less work and there was less and less for him to do) so I put my hand up and the teacher gave me a strange smile and said, “Oh, you can put your hand down.” I felt rather badly about it because there were really poor then and for us it didn’t count. For us it was like not having the pudding in the restaurant.’

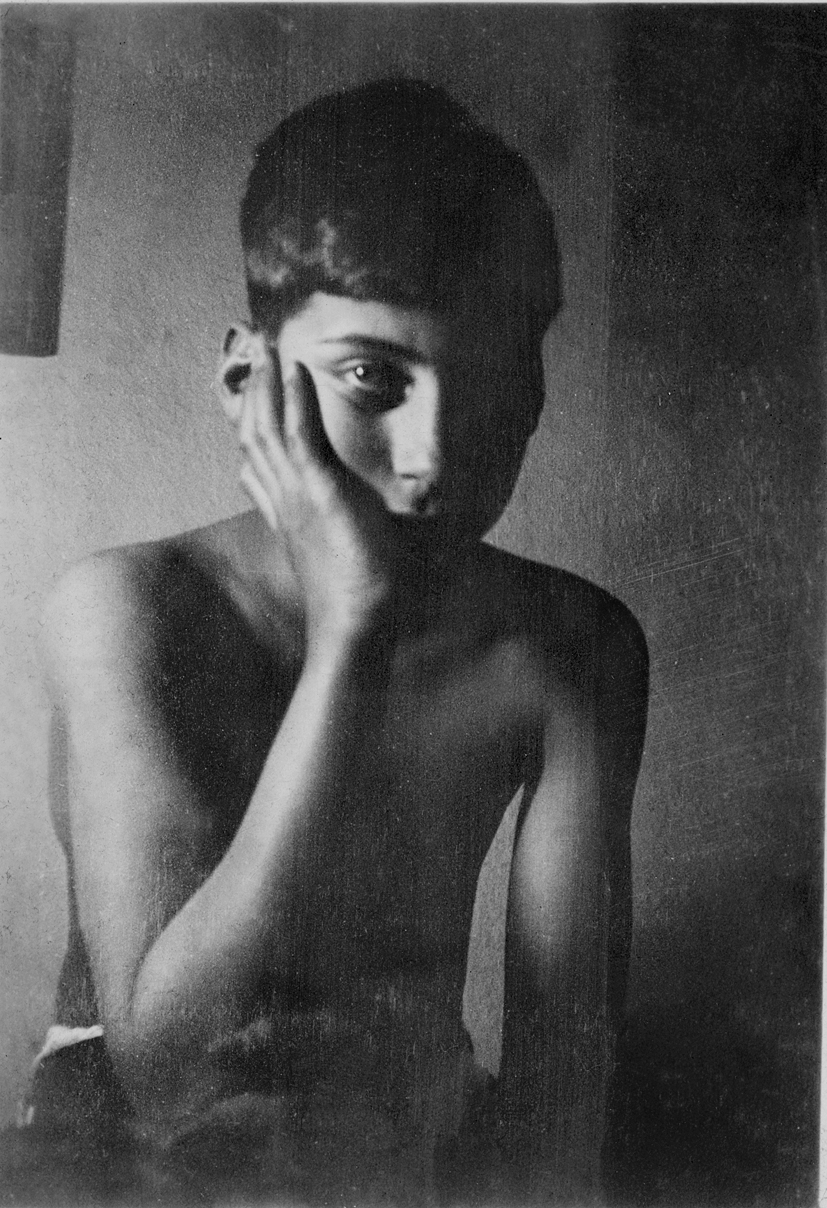

Lucian c.1929

Going down the street with his mother one day Lucian started chalking swastikas on the wall. Puzzled at her appalled reaction, he told her that it was just something all his friends did. By then he was involved with a school gang that went in for lighting fires and minor daredevilry, behaviour inspired, where Lucian was concerned, by Erich Kästner’s Emil and the Detectives (published in 1928, filmed in 1931 with a script by Kästner and Billy Wilder) in which a pack of boys from Wilmersdorf, the neighbouring working-class district, outwit a bank robber turned pickpocket. Being the keenest and smallest in the gang, Lucian was the one who volunteered to go into the shop on the way home from school to pocket Trumpf chocolate. However, he found himself excluded from the new after-school activity: Hitler Youth meetings. Unlike all but two of the others he was ineligible. His classmates told him that he wasn’t missing much. ‘“Don’t worry,” they said, “Thursday afternoons we just sing songs and eat sausages.”

‘Strange as it may sound, at that age, a great deal of my conversation with the other boys was about politics. I was aware of the excitement. I listened very much: “Vote for Hitler or Hindenberg.” I remember these words like Reichskanzler [Reich Chancellor], which I’d never heard before.’

In 1931 the Ullsteins moved away from Regentenstrasse because they objected to being overshadowed by a ten-storey office block erected next door to them beside the Landwehrkanal: the Shell-Haus by Emil Fahrenkamp, in the International Modern Style, later to become headquarters of the Navy High Command and one of the few buildings in the district that was to survive the war. The Freuds moved as well, though not to avoid modernism, to the nearby Matthäikirchstrasse 4, to a large early nineteenth-century apartment, more elegant than Regentenstrasse, with a garden just big enough for athletics. ‘I had the idea of training for the long jump. It was better doing it with someone else, especially someone who was worse; not someone that, in the ordinary way, I’d have chosen.’ The boy was called Goldschmidt. ‘He’d got that special thing, it’s a kind of Jewish upbringing thing, which makes people opposite of athletic. Isaiah Berlin had it: indoor characteristics, basically unphysical. It doesn’t show when older.’

In November 1931 all three brothers caught scarlet fever and were kept indoors for six weeks, during which time they were sent commiserations from the school on Hiddensee. ‘It was to do with my governess who was courted by the schoolmaster, Dr Heldige: a huge package of letters from Hiddensee to Berlin. One of them said, “I’m afraid I’m new so I don’t know how to write to you.”’ Their mother wrote to her in-laws that, when released from their seclusion, the boys ‘flew and leapt down the stairs in a way that frightened and alarmed me’.

The Chinese matting in the apartment corridors was good to slide on. ‘I slid very fast and went through a glass door. My father’s horrible partner, Mr Kurtz (“Shorty”), who was hugely tall and, like all the assistants, in love with my mother, held my wrist hard to stop me from bleeding to death. It missed the artery by millimetres, so after that I had to write with my right hand. It was neater than my present writing; because it was Gothic writing with so many loops that I could fill in with colour. The scar weakened my wrist. I was always left-handed and there was a certain amount of talk about it.’ His mother kept a poem for Kurtz that he wrote in his new right-handed script:

Lieber Kurz

Hertzliche gluckliche wunsche

Zum Kurzen geburtstag

Ich habe Kurzlich gehort

Das du 3 zentimeter

Kurzer geworden

Ich habe nur Kurze

Zeit und muss bald

Kurzschbuss machen

Giete grusso von

Mir

Lux

Dear Kurz

Very happy short birthday

I heard shortly

That you are 3 cms shorter

I only have a short time

And must soon

Cut this short.

Lots of love

Lux

While memory isolates incidents, photographs flatten them. Family photos, particularly, lose immediacy and become just typical; within a few years they look quaint, a little while longer and pathos obtains. The three young Freuds posed in long trousers is one of those countless photographs that, had they not left Germany, would have been seen subsequently to foreshadow fate. ‘Me and my two brothers, in Berlin, in tailored clothes, which I find is a bit like, “all those lovely boys ended up in gas ovens”. Those dark looks.

‘I love German poetry but I loathe the German language.’

In January 1933 President von Hindenburg made Hitler Chancellor. A month later the Reichstag fire and the orchestrated commotion the next morning meant a detour for Lucian on the way to his new school on the other side of Unter den Linden: the Französisches Gymnasium, where Embassy children were sent and French was spoken. Not that he went much. ‘I was ill with all the different things as a child and I never caught on there at all.’ He saw Hitler once in Matthäikirchplatz. ‘He had huge people on either side of him and he was tiny.

‘On Unter den Linden, on the side we used to walk down, there was Siegesallee [Victory Alley] and there were all the kings and emperors of Germany in marble and bronze, and one of the German kings that amused us – you know how children love fat people – was Karl the Fat. My Mosse cousins had an uncle – a relative – called Karl Selowsky who was a lawyer, quite young, and enormous and we thought he was wonderful. And then a terrible thing happened. On the way to his office (he was well-to-do and lived very well, no doubt that was why he was so enormous) he was got hold of by some Brownshirts and was badly beaten up and this news filtered through and seemed pretty terrible, but then he was OK and out again.’ Selowsky survived the war – in France – and became a judge in Karlsruhe.

The Mosse children’s uncle, Rudolf Mosse – a German nationalist who became an officer in the war, won the Iron Cross first class and was supposed to go into the publishing business – had decided instead to take up farming, so he ran the family estate near Potsdam. According to Dick ‘Wolfi’ Mosse, ‘He tangled with the local Nazis, who didn’t like Jews as Prussian officers or as farmers. He was beaten up and arrested in 1933 at five in the morning and, whether he threw himself under a lorry on his way to the concentration camp or was thrown, either way, his body was delivered in a coffin.’ Sigmund Freud’s comment was that ‘Jews owning land was an obscenity to them as Jews were a “nomadic” race.’10

In April 1933 the first boycott of Jewish shops was staged (‘I didn’t know there were Jewish shops’) and the banning of Jewish lawyers and doctors and other professions began. Ernst’s brother, Great-Uncle Olli, a civil engineer, left Berlin for Paris. There were meetings round the dinner table, the Freuds and friends debating what to do, whether to wait and see or leave forthwith. In May Ernst Freud, visiting his father in Vienna, mentioned Palestine as a possibility. Clement, whose turn it was to go with him, told his grandfather that he was referred to at school as ‘Jud Freud’. Book-burnings were organised in Berlin with verbose damnations for the works of certain writers: ‘Against soul-disintegrating exaggeration of the instinctual life I commit to the flames the writings of … Sigmund Freud’ was an official line.

According to Lucie Freud, rich German Jews had taken to going to England to give birth, thereby endowing the baby with a place-name on birth certificate and passport that would serve to impress officials; she and Ernst, however, had no reason to regret their lack of foresight in this respect. When I first met him, Freud told me that his parents had planned leaving before Hitler came to power and sent money well in advance. In 1933 quitting Germany was a relatively straightforward business. Fifty thousand Jews left in the course of the year; obstructions and confiscations (‘flight taxes’) were not yet in place and there was little idea of any worse fate than penury and disqualification. For the Freuds the move, as Lucian remembered, was fairly easy. ‘It’s not that we were well-to-do, but we were reasonably comfortable. Lots of Jewish people in similar positions, or perhaps more wealthy people, didn’t think it could happen, didn’t think it would go that far, didn’t believe it.’ Having decided to move to England Ernst went ahead to London to see if there were any prospects for him there and to find a suitable school for the boys. While there he attempted to strike up useful contacts: Erich Mendelsohn, who had already moved there; his one-time employer in Munich, Fritz Landauer, who also had settled in London; and he showed his work to Edwin Lutyens, the top name in British architecture at the time. Robert Lutyens his son was a possible partner, he thought. He saw the need to publicise himself. Homes and Gardens was to publish, in March 1934, an account of his Scherk house of 1931 in Berlin. He secured reduced fees meanwhile for the boys at Dartington School in Devon.

While he was away Lucie took Gab (Stephen) to see Mae West in I’m No Angel. Lucian, she said, wasn’t old enough.

In July the two younger boys, together with their cousin Jo Mosse and a couple of others, went on a three-week camping trip to the lakes and rivers of Mecklenburg. This was, Lucian felt, ‘a kind of toughening-up treat’. The Edvige II, a motorboat, with portholes in each side and an awning at the stern, operated as the Seeschule Racki, Racki being the skipper, ‘a good-looking, big, young non-Jewish type. He was rough and tough: he taught us swimming by pushing us in. We kept a log and Racki made a film with a commentary and it said about me: “Lucian, over-excited as always …”’ On the bank of one of the lakes they spotted a lunatic with a bucket on his head making a speech thinking he was Hindenburg.

‘We were already planning going to England so Racki taught us what he said were English swear words. “Burrshit,” he said.’

For some months there had been English lessons. ‘The first book I read in English was Black Beauty. Actually Alice in Wonderland was the first, but I didn’t understand it fully. I remember trying to read it at Cottbus; being there, with the ice-house outside the sitting room, me being with my mother and saying the first sentence: “Alice was beginning to get very tired of sitting by her sister on the bank, and of having nothing to do …” And down the rabbit hole she went, “never once considering how in the world she was to get out again”.’

In one of the letters Lucian wrote to his father with news of his swimming and long-jumping, a haircut and new check trousers, he added as an illustrative footnote a cheerful little talking skyscraper that said, ‘Scrape me break me cloud then Unemployed Freud can build me again.’11

This was optimistic. For when it came to making the break from one way of life to another with no welcome and hardly any likelihood of return, the shock of dislocation could be devastating, as their neighbours the Hamburgers found when in November 1933 they left Berlin. Michael Hamburger was sent to school the day after they arrived in Edinburgh. ‘I and my younger brother walked to school unaccompanied – in Berlin we always had our governess with us – because we were all under such extreme stress: Father had to pass all his exams in one year to be allowed to practise in England and mother, confronted with an extremely cold house where in the past she had had servants, could spare no time for us. My brother was weeping. We spoke no English and didn’t know where we were.’12 Soon afterwards they moved from Edinburgh to Hove, then to St John’s Wood.

Bertrand Russell, writing that October in a news magazine, Everyman, on ‘Why Are Alien Groups Hated?’, talked about the revival of ‘utterly unreasonable dislikes’ in Germany in the months since the Nazis had acquired power. ‘Spain ruined itself by the expulsion of the Jews and Moors. In almost every white man’s country, the average among Jews is higher than amongst the rest of the population, not only in intelligence, but in public spirit, in artistic capacity, in industry, in fact in almost every valuable quality.’13 A subsequent editor of Everyman, Major F. Yeats-Brown, who described himself as ‘friendly to British Jews’, was more enthusiastic than his distinguished contributor about ‘the active, integral, authoritarian state’ that Germany was fast becoming. English tourists, he reported, came back impressed with the ‘spirit of business-as-usual and cheerful self-respect’. So-called ‘Down-and-outs’, he added, ‘are collected into Labour Camps and provided with work, clothing, food, pocket money. Youths of both sexes possess magnificent physiques … Hard work and serious play are the order of the day. Germany is pre-War. The Jews are ostracised as they were then. France is hated, England half-envied, half-despised.’14 Ernst Freud remarked that English people were welcoming, though when they said something nice about Hitler, thinking to be friendly, he was speechless.

Immediately before leaving Germany the Freuds went to stay in Vienna, all of them except Lucian. ‘We could choose and I refused and went to my Calmann cousins in Hamburg.’ Then they left. ‘It was just in time. Afterwards it became much more difficult. We weren’t refugees, we were émigrés.’ Being émigrés they could take all they wanted with them. Money over and above the amount allowed out with them was hidden in the leg of a circular table with a red marble top, designed by Ernst, though not with concealment in mind. The household dispersed. Kurtz worked as a servant for a while in Scotland, Ernst’s other assistant Augenfelt came with them, and Linde the governess too, but she returned to Germany shortly before the war and went into a nunnery. Grandmother Brasch remained in Berlin. ‘She stayed on and came just before the war with just the five pounds which was allowed.’ Forced to divest herself of Gross Gaglow, she sold it to a Zionist organisation set up to train Jews for work on the land in Israel. This was soon forfeit.

The Regentenstrasse neighbourhood became a diplomatic quarter where the embassies and legations of Axis-friendly or Axis-acquired countries accumulated, among them those of Austria, Argentina, Greece, Japan, Hungary, Romania, Spain and Yugoslavia.