‘I used to always put secrets in. I still do’

In 1940 Ernst Freud was commissioned to convert part of the Good Housekeeping Institute in Grosvenor Gardens into a British Restaurant, one of more than 2,000 set up under the auspices of the Ministry of Food ‘to secure minimum nutritional standards for members of the population hitherto unaccustomed to take substantial meals away from home’.1 Following on from that he was asked to design a test kitchen and laundry for the Cookery School. A mural was required for the shutter on the serving counter in the canteen and Ernst Freud got Lucian to submit a sketch for one. It was accepted. It was Landscape with Birds once again, this time with bats: ‘a fortnight’s hard work. I had a lot of bats flying around, and then I put in a man. It was horrible, they said, and Father sided against me. He said he’d had trouble enough persuading them to let him do it in the first place. They painted it out.’

Later on he did another mural, for a club in Leicester Square (‘these clubs all had Caribbean names’) involving ‘sinister men sitting on horses glowering at the dancers’ in orange, yellow and black pastel on rough walls. ‘Payment was two weeks at the club but I had just one night: the club was closed down just before I finished. I’d been hoping to get free drinks there.’ He also painted a mural for ‘some coffee stall off Leicester Square: the Anglo-Russian Café. When Russia came into the war, suddenly all the people who had pretended to be English decided it was time to be ethnic a bit. A displaced person – the sort of person who taught or had a café and made sandwiches and wasn’t interned – asked me. I did one wall and Johnny Craxton did the other.’

Freud first got to know Craxton towards the end of 1941. Two months older than him, and several inches taller, Craxton was musical (his father Harold was a pianist and professor at the Royal College of Music); he had been brought up in a crowded bohemian household in Hampstead. He was a sociable being, considerably better versed and connected in cultural matters than Freud. He had even seen Guernica in its original location, the Spanish Pavilion at the International Exhibition in Paris in 1938. In 1939 he had enrolled at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris to do life drawing. The Craxtons had been bombed out of their house in Hampstead in January 1941 and were living – all five of them – in a tiny flat in St John’s Wood. Craxton was exempt from military service: a history of pleurisy. Through the musician James Iliff, from Bryanston, Freud got to hear of the lively Johnny Craxton with his signature style (he liked to think of himself, he used to say, ‘as a kind of Arcadian’) and he went to the Craxtons’ flat asking for him and, told that he was away in Dorset, left a note suggesting that they should meet.

Another beginner, similarly declared prodigious and several phases ahead of Freud in 1942 in terms of self-promotion and recognised achievement, was Michael Ayrton, recently discharged from the RAF (he kept the greatcoat) and at twenty-one already a developed bohemian character with beard and shooting stick and hair slicked back. He and his art-school friend John Minton had exhibited together at the Lefevre Gallery in 1940, and in 1942 jointly designed a production of Macbeth for John Gielgud. Having studied in Paris, Ayrton boasted acquaintance with Berman, Bérard and Pavel Tchelitchew, the three founts of Neo-Romantic expression. The self-styled ‘suave little Ayrton’ invited Freud to come and see his paintings. He lived round the corner from Maresfield Gardens.

‘I went to the house, a big ugly house in Belsize Park, and handed my coat to a woman who turned out to be Ayrton’s mother. We went upstairs, he showed me the paintings and I said very little, just “I like that one best,” felt I had to go and as I went he leant over the banisters and shouted down, “Why don’t you like my pictures?” and I got out quick.

‘I was conscious of his superiority – knowing Tchelitchew, Berman and life in Paris – but because of the twisted way he worked I had some contempt for it. I didn’t get even a whiff, like from Cocteau or even from Miró’s Harlequin’s Carnival: he was much nearer to Arthur Rackham. His manner was so nauseating: a bogus insider talking. I can remember being rather touched at Johnny Minton’s being sort of in love with Ayrton. But he was odious.’ Minton wrote him a letter which, seeing that it was laudatory, Ayrton kept in his wallet for others to admire.

‘Unfortunately I had told him that I had this girlfriend, Lulu, and that I had had a dream that he was with her. But he drew himself up and said grandly, “Oh, you need have no worry on that score.”’

Lulu was Lorenza Harris, another Coffee An’ girl. ‘A glamorous, dazzling blonde from Wimbledon; it was with her that I went into my first pub, with Iron Foot Jack. We went to the Fitzroy and as I had never been to a pub, when he said, “Have you got the admission fee?” I thought it must be like a club, but it was his genteel way of saying have you got enough for a drink. What would I have? “Whisky,” I said, as it was all I had heard of. Lulu was sulky and nice. I went out with her for some months, but I never had any money and she wanted to go to the cinema and restaurants. I wanted her to be completely devoted to all my wishes and decisions and she wasn’t at all.’ He was photographed with Lulu on the roof of 2 Maresfield Gardens. He had put a chair on the leads for sunbathing. ‘I quite liked the idea of a photo of me and her. I’d seen a still of Rudolph Valentino as the Sheik and thought I’d like her at my feet, so I asked Frankie Goodman to take some, in an appropriate film-noir style. Frankie had been one of the bright young things with the Tree sisters and Cecil Beaton. I met him I think in the Coffee An’, then he joined the army and wrote me some letters. One of them said something funny: “I feel I must write to the little friend at home and you are the only candidate.”’

The Lulu affair soon waned. ‘I didn’t get on with her father, who was a great admirer of Sir Richard Acland.’ (Acland was an MP and the proponent of a liberal world order.) ‘He saw me at Roehampton swimming pool drawing and was deeply impressed; but I never had any money.’ The end came with a sudden spat. ‘We were walking down Piccadilly past the RA and she said weren’t the gates beautiful? I said they were horrible and pretentious and she got very het up and we parted and that was it.’

The deep basement of the Coffee An’ gave shelter during air raids: ‘A sense of (probably false) security’, a showbiz journalist Peter Noble wrote in his memoirs Reflected Glory published in 1958. ‘Lucian Freud was a regular here. Pale, excitable, good-looking, he usually attracted a group of fellow-artists to his corner table, as well as several exotic-looking actresses and artists’ models (all of whom seemed to be in love with him!). Quarrels broke out around him, and occasional fights, but Freud remained imperturbable, a cigarette permanently in his mouth, his dark eyes glistening with amusement.’2

Paper rationing and distribution problems shrank Horizon and prompted an appeal from Cyril Connolly, published in the February 1941 number, asking readers to reward individual contributors with tips. ‘Not more than One Hundred Pounds: that would be bad for his character. Not less than Half a Crown: that would be bad for yours.’ He went on to solicit, primarily on his own behalf, food boxes from the United States.

The same issue carried an advertisement for the East Anglian School at Benton End offering ‘instruction in the new forms and their recent development’. This meant not War Art – too current a genre – but ‘landscape, head and figure from the model, birds, animals, flowers, design’. As it happened that month Freud won a competition set for the students by Allan Walton for a fabric design. His motif was horses. ‘Horse with a repeat of jumps; it was produced as a textile, but instead of my careful spacing they put a wiggle in the space.’ He spent the prize money on a ticket to Liverpool. Skip over water, dance over sea: since his eighteenth birthday in December he had been old enough for conscription, but that was not the reason he decided to try his luck in the Merchant Navy.

John Masefield’s poem ‘Dauber’, screeds of which Freud had learnt by heart at school, tells of a sensitive lad, a would-be artist, ‘young for his years and not yet twenty-two’, who becomes the ship’s lamp man and painter. For Dauber the seafaring life was the attraction:

The fo’c’sles with the men there, dripping wet:

I know the subjects that I want to get.

Freud did not enlist for artistic purposes. He had an urge. ‘I never asked myself why. I won the prize – Allan Walton gave £25 – so I went to Liverpool with the object of getting on a ship. Cedric and Lett knew Jack Barker, so I didn’t exactly scarper there. I think I wrote to Cedric.’ That he may have done, but he told his parents nothing except that he was going to Liverpool while telling others that he was off on an exploit. Looking back with seventy years’ hindsight Felicity Belfield wondered whether this was a sort of escape attempt. ‘That was a time when England was expecting to be invaded and his parents perhaps encouraged him to go abroad.’ Freud insisted that this was not what he had had in mind. Fear of remaining in Britain, prey to invaders, just didn’t come into it. He thought of it as something of an excursion, that’s to say a return trip: an epic jaunt.

He got the idea from Jack Barker, a Suffolk friend, ‘a completely wild merchant seaman, amazing, mad, gave wild parties’. Barker had served on windjammers and later on was to open, the blurb of one of his books claimed, ‘the most successful fish and chip shop in the history of New York’; to Freud he was a figure of reckless charm, seven years older than him and in every way more experienced. There had been an affair with Stephen Spender in the summer of 1939 during which Spender wrote of him (‘Jack Tar on the slippery boards’) as ‘trim-waisted, cliff-chested’;3 a year later he had stopped off in New York, stayed in Brooklyn with W. H. Auden and began an affair with Auden’s lover Chester Kallman. Back in England he made it sound easy to cross the Atlantic regardless of the war simply by signing on. Freud was convinced. ‘He was completely available for either sex; Auden influenced his trying to get hold of everyone, he was pathetic really. Jack Barker had this idea, and so I had this crazy idea, to “meet Judy Garland” in New York.’ It was essentially a Wizard of Oz odyssey that he envisaged. Merchant seamen could get to Oz. Barker had contacts in New York, Peggy Guggenheim for one, and only by North Atlantic convoy could one hope to get there. With Michael Nelson and a friend of Barker, Tony Jacobi (‘queer, my parents knew him’), Freud went to Liverpool to find a ship.

Barker’s father, Lieutenant-General Michael Barker, a Boer War veteran prominent in Dedham society (‘Lett-Haines loved saying “General Barker”’) had been relieved of command of I Corps of the British Expeditionary Force at Dunkirk and in the spring of 1941 happened to be employed checking security in the Liverpool docks. ‘Through Jack he recommended me for a seaman’s card; Jack said a friend had lost it.’ Old hands in the Seamen’s Home advised him to say that he had been torpedoed and lost his papers, which would explain why he needed a card and had no kit.

‘I liked the idea of adventure – The Ancient Mariner – but I was soon pretty desperate. The man who ran the Seamen’s Home made it clear that you could go to bed with him and stay there free, so I went to Mrs Schwenter’s boarding house where the others were.’ This was an experience in itself. ‘I was very conscious, for the first time, of Catholic dirt: a poor boarding house with samplers and holy pictures and everything covered in bacon grease.’

Tony Jacobi secured a berth immediately (‘Such a tart: could be used instead of the rubber blown-up girl the bo’sun had on the ship’), and after several rebuffs Freud managed to get a berth on a New Zealand vessel. He got tonsillitis, however – ‘I’d been rather ill, on and off’ – and the ship left without him. He later heard that it had been sunk.

Having kitted himself out with a jersey and seaboots he returned to London for a few days and, keen to show off, went to the Ritz Bar. ‘I had my white gumboots on and was so proud, but I was barred. “I’m afraid we can’t let you in,” the man said, “as there’s royalty present.” It was King Zog of Albania and his seven sisters.’

Returning to Liverpool, he succeeded in securing a berth on the SS Baltrover. ‘I walked on to a ship and the man said “fine”; I didn’t realise he was just the man on the gangway.’ He was readily signed on, somewhat to his surprise, but soon found out why. The ship, a tramp, smallish at 4,900 tons and built in 1913, had been commissioned twice as a merchant cruiser, in 1914 and in 1940. Pre-war she had been sold to the United Baltic Corporation in London for cruises from England to Gdynia and Gdańsk on the Baltic. ‘It had a terrible list and was very very slow; it was chartered by Furness Withy to do the Atlantic runs for which it was entirely unfitted.’ Six years later, in reminiscent mood, talking to a war hero on a yacht in the Aegean, Freud said that when he signed on the ship’s mate told him: “This trip will be the making of you, my lad. You can’t tie a clove hitch yet, but when you get back to England you will be a man.’4

The ship’s log shows that the voyage began, technically speaking, on 7 January 1941, and that Freud enlisted on 5 March, as an ordinary seaman.5 He was the youngest member of the crew of about sixty men. ‘The Baltrover, I discovered, didn’t carry deck boys and had a terrific job getting crew. It took passengers and was slightly more comfortable than most, so it was the commodore ship when we went out. The ship was manned for the Baltic run, when the war broke out: half British and half Balts – all the fire people in the engine room were Balts – and when the ship was in British waters they were given the alternative of being interned or working at full pay as prisoners on the ship. Going out with all those Estonians in the engine room: imagine the atmosphere when we were being bombed.’

The rest of the crew were housed in the fo’c’sle, where Christie the bo’sun dared not enter. ‘It was pretty anarchic there. Christie, a last-minute replacement, had a wooden leg with a doorstopper on the foot. He used drawing pins to keep his sock up.

‘I thought I’d been brilliantly clever to get on to this ship and, until I started working, they thought they’d been quite clever to get me.

‘I worked on the ship when it was in port for two or three weeks; I was set to watch the cargo being loaded as they thought I was the most honest person. One of the sailors said, “Look, I’ll give you a tip. There’s a lot of drink in this cargo and they all have these knives. Unless you split one of these cases open and share it among the dockers who are loading they will DO you with one of these. That’s why there are so many people with missing arms and legs around.” There certainly were, so I said thanks, opened a case, gave them one each and thought I don’t see why they should have them all. So I put six bottles of Drambuie into my sack, which I thought would be nice for a rainy day.’

He didn’t have to stay on the ship when ‘working by’ and, as it happened, social life came his way. The show Sweet and Low, with Hermione Baddeley, was in Liverpool and a member of the cast, Joy Penrose, sent a telegram to the Baltrover saying, ‘Hope you can meet at 8 at the Adelphi.’ News of this assignation at Liverpool’s poshest hotel spread and Freud was stuck with a lah-di-dah reputation. ‘Such a thing had never happened,’ he said. ‘“Fucking drink in the Adelphi?” they jeered. “Oh yes, you’ll be late at the Adelphi.”’ Off he went, determined to impress the touring company. Up Lime Street he strode in his seaboots, the Liverpudlian song ‘Maggie May’ running through his head:

She pox’d up all the sailors

From the skippers to the whalers …

She’ll never walk down Lime Street any more …

‘In my seaboots I came into the Adelphi and into the bar where only men were allowed (apart from Hermione Baddeley and Joy Penrose) and got almost as much attention as I wanted. I thought I was living it up and they thought they were seeing life.’

On the night of 12–13 March the Luftwaffe attacked Liverpool. ‘It was very exciting. Planes came and sprayed the docks with firebombs and in my special boots I had to kick them off the deck. Absolutely marvellous I thought this. So exciting.’

Two days later, with a cargo of Drambuie and shoes (‘booze and shoes: to stop thefts they sent left feet only and the next trip sent right feet’), the Baltrover set out under Captain Wells as commodore ship of Convoy OB.298: thirty merchant ships and eleven naval escorts. Sailing at the speed of the slowest, ‘absolute crocks, less than walking pace’, they took over a fortnight to reach Halifax, Nova Scotia. There they berthed for a week, then went on to St John’s Newfoundland and back to Halifax before returning to Liverpool.

The crew did not know what to make of Freud. There was his black and white towelling gown. ‘I’ve always liked these gowns: “Sheikh of Araby”, they called me, and “Jack Shitehawk”, as I ate so much (it’s their word for vulture).’ Another name they gave him was Lucie Walters. ‘They were puzzled, but they were all right, they just couldn’t understand what I was doing there. During a storm they’d say, “This isn’t the fucking Adelphi Hotel.”’ He soon had to defend himself from their attentions. They took to waking him up every two hours when he was off-watch. ‘Coming off watch at three in the morning, to sleep in a tin bunk, someone would come in and stick a cigarette on my neck – they had saltpetre cigarettes that would burn even in the wind – and say, “Time you had a pee.”

‘Some of the sailors were in the most terrible state. One way of getting money was to get money for gear after you’d been torpedoed: they’d taken the money and not bothered to get the clothes; they thought they were on a winner. In the freezing cold I was the only person who had two jerseys and boots.’ They were curiously competitive. ‘When the men got drunk they started doing very complicated knots: showing off. And everything they despised, which was to do with learning, it suddenly came out.’ They suspected Freud of signing on in order to write a book.

He had brought paints with him in his sack, imagining he’d have a fair amount of spare time. ‘I hadn’t taken much, but I brought the paints: absolutely mad. I had some very strange assumptions.’ His inks came in handy though. ‘They were useful for tattoos. Several of the crew wanted to be done. We discussed the designs. It depended on them what I did: birds and fish, hearts and arrows. Some had “love” and “hate” on them, and people and fiends. The scab forms and then you rub ink in. Indian ink came out a very deep blue.’ Some he drew. John Boeckl, a pensive twenty-three-year-old Czech seaman from Kobe in Japan, went into the Swift layout pad, and one day, after carrying food for the umpteenth time from galley to fo’c’sle, Freud did the cook from memory, unshaved, cigarette in mouth and cap on head in a collapsed state. A more elaborate drawing of the ship’s gunner in a duffel coat was possible because, being assigned to the ship by the Royal Navy, he had to have his own quarters under the deck hut housing the four-inch gun.

Naval Gunner, 1941

Like Maldoror, Freud watched ‘the living waves, dying one upon the other, monotonously’, saw the seas fancifully addressed by Lautréamont (‘Ancient ocean: you resemble somewhat those azure marks to be seen on the bruised backs of cabin boys; you are an enormous bruise upon the earth’s body’) and, like Masefield’s Dauber ‘drawing the leap of water off the side’, he drew the lifting sea, a patch of it, mid-distance. ‘With semi-dolphin. I did report a submarine but it was a whale fin and I got a bollocking.

‘One or two of the men had been on the clippers and they’d say, “I’ll show you how to fucking draw,” and they’d do a thing with all the rigging.’

For a few days it seemed that this convoy experience would be uneventful, at least in newsreel terms. Then, suddenly, on the fourth day out there was violent, close-up action. ‘On the first or second day the German planes saw us and on the third or fourth day there was this raid. When we were attacked we could see the tracer bullets and the plane was so low you could practically see the grins on people’s faces, like in a comic. When at dawn and dusk the German planes circled the convoy, we sent the message “identify yourself”. Instead, they swooped low over the convoy dropping bombs. The ship behind us was hit. It was a tanker.’ Laden with ammunition (not oil) for Singapore the Benvorlich was attacked near Bloody Foreland, at the dispersal point where the convoy was to divide: part continuing to Halifax and part to Gibraltar. ‘Two lifeboats got away and then the whole thing went up into the air, the entire ship. Bits of the ship and bits of people rained all over and there was a cloud, like an atomic cloud – in fact years later, when I saw the atomic pictures, they looked very familiar – and then the ship was blazing and exploding as the fire got into the hold. Explosions followed by explosions, getting higher and higher: it must have been ammunition, which you don’t expect in a tanker. Not surprisingly, after that, the morale on our ship was very low.’

Just about the only shipmate Freud got on with was Boeckl, the Czech who, obliged to do so by Ship’s Rules (‘The one to which communications should be made in the event of the death of the Seaman’), gave his home address as Kobe. ‘He spoke German and knew poetry; he knew Goethe and could talk about it.’ Boeckl was an able seaman and well able to look after himself. ‘He was sitting in the fo’c’sle with stockings for his girlfriend and holding them up and stroking them and no one tried to pick a fight with him. He kept to himself with a grey box which he fiddled with all the time.’ This aroused suspicion, making him and Freud the ship’s two oddities.

Although the cargo was destined for New York, the Baltrover was too decrepit to pass inspection there so they unloaded in Halifax. For two days before docking Freud had been excused duty. This was recorded in the log – 29 March: ‘Ship’s surgeon says he has tonsillitis and sore throat and is unwell. Temp. 30 3:Ln Freude O.S. Ref LOI8 improving but still off duty.’

Were he to slip off to New York, now was the opportunity. Getting Boeckl to keep an eye on his things, maybe for good, Freud went ashore, spent a day wandering around in the wet and a night in a freezing YMCA air-raid shelter. This was misery enough to convince him that desertion wasn’t a good idea, so he returned to the Baltrover only to find that he hadn’t been missed. ‘Sailors were often away overnight with their whores.’ His possessions however had already been distributed among the crew and it was two days before he saw the consequence of that. ‘I couldn’t put two and two together. The men, lots of them, couldn’t turn-to, they were feeling so ill. All the bottles of Drambuie had gone and they said the bo’sun, who had already been fined for being drunk and for bringing on board intoxicating liquor, had been sniffing round my sea-bag; so I jumped on the bo’sun, who had this terrifying syphilitic nose, and it was only by pressing his ear against a steam pipe that I managed to get away. He was really horrible. He used to threaten us. He’d say, “I’ll kill you’s all, and if I can’t kill you with my bleedin’ hands, I’ll kill you all with fuckin’ work.”’

This went down in the ship’s log in summary form. ‘J. Christie was drunk again and creating a disturbance in engineer’s alleyway. Fine ten shillings.’

‘The bo’sun was frightened. He was supposed to inspect the fo’c’sle but as he never dared go down there in fact he never saw my sea-bag. Anyway, of course, the men had taken all the Drambuie and drunk it. Afterwards, on the way back, they said, “What’s this stuff, this Drambuie?” I said, “Oh you wouldn’t like it; it’s an acquired taste,” and one of them said, “We fucking acquired it.”’

Alerted perhaps by the rumpus, Higgins the Second Officer became suspicious of Freud’s papers and reported him to the immigration authorities, who came on board to check. ‘He said I was an odd bird and what was I doing on board ship? He thought I might be some sort of spy because my birthplace was Berlin and my date of naturalisation – 1939 – was highly irregular because no one was naturalised at that time. Higgins had an odd attitude to me. I felt that, much as I liked being misunderstood, he actually couldn’t understand and vaguely looked to catch me out. He did more than his duty; and certainly duty couldn’t explain my presence.’

As it happened the Canadian authorities were quick to confirm that Freud was a certified British subject, which, if anything, increased his peculiarity in the eyes of the crew. They noticed that unlike most of them he didn’t go off to the brothels where women, tagged ‘White Boots’ and brought in from Montreal, serviced shore parties. ‘No money. I was told once (by the Head of Medieval Antiquities at the British Museum) that Furness Withy arranged that when you had a whore you gave them a chit to get paid by the office. That was in London. One of the sailors was in America, he was having a whore, she was reading a newspaper and she looked up over it, put down her paper and said, “Limey, have you slimed yet?” Well, even he thought that a bit rough.’

Cold-shouldered by his shipmates, in Halifax he wandered around the streets on his own, bought himself a dark-green corduroy cap with flaps and went to the cinema. They were showing the Preston Sturges comedy The Lady Eve, with Barbara Stanwyck as a cardsharper’s daughter and Henry Fonda as the innocent son of a millionaire. He enjoyed it but when he got back to the ship they asked him what he had been up to and he was caught out. ‘I said, “Oh, I found a marvellous girl: we went to the cinema.” But it turned out that some of them had been in the cinema, sitting behind me, and had noticed that I was on my own.’

He tried bluff. ‘You just didn’t see her: she was very small.’

‘Did you go with her?’ they asked and all he could say was – very Henry Fonda – ‘A gentleman’s lips are sealed on this subject.’

‘They took me less seriously after that. I felt badly about it. I thought I’d better give up lying in future.’

After about a week the Baltrover was directed southwards and around Cape Sable to St John, New Brunswick, to pick up loggers for service in Scotland, recruits to the Newfoundland Forestry Unit set up by the Ministry of Supply early in the war: a consignment of boys, ‘illiterate and very wild’. Freud liked them. Newfoundland girls, he had discovered, knew how to read and write but boys didn’t. He especially liked the Eskimo ones. The mate set them to painting everything on the ship that could be painted. Then they went back to Halifax. ‘The thing that terrified me was tying up the ship. It was explained to me why so many dockers had arms and legs missing, chiefly legs: they had been hit by these wires. So I used to go and hide when the ship docked.’ Three of the crew deserted; two of them were caught and put back on board before the convoy sailed.

On the voyage out Freud had found that his left hand, injured when he went through the glass door of the Matthäikirchstrasse apartment, felt the cold particularly acutely. Off Newfoundland, heading into the Arctic, winter temperatures resumed. ‘Every time I put my rag in the bucket for a few seconds it was frozen.’ Set washing the winches he would be swept off his feet; looking up he’d see the steersman smile, the joke being that he had deliberately steered into the swell so that a wave would slosh him across the deck. ‘Three watches (nine or twelve men) meant that they had to do my work virtually. The watches were eight hours on four hours off all through the day and night and, each separate watch, one had to steer and one was the lookout man and I can’t remember what the third one was. I was useless.’

He carried food from galley to fo’c’sle, scrubbed, sluiced, cleaned and greased the winches. Once, just the once, he was told to man the wheel and, failing to grasp why it took so long for the rudder to respond, he steered the ship off course. ‘Steering only reacts fifteen or twenty seconds after you’ve turned the wheel, so by the time that you have realised you’ve done it wrong it gets worse and worse. I was doing my absolute best but the crew thought that I was deliberately swinging the lead. They thought I was a joke. Sometimes they thought that it wasn’t a very good joke, that I was endangering them.’

The convoy to Liverpool was sent on a zigzag route taking thirty-four days at a maximum speed of nine knots. In those weeks, April to May, nearly 200 merchantmen were sunk; it was one of the worst periods for losses in the Battle of the Atlantic and although the Baltrover reached home waters unscathed it was to find Merseyside being blitzed night after night, leaving nearly 2,000 dead and 75,000 homeless, so for several days they had to lie at anchor outside the docks.

By then Freud had had enough. He went to the ship’s doctor, a twenty-six-year-old whose first experience of convoy this had been. ‘He was called Tapissier and was known as Tap. My larynx was bleeding, I was pretty weak; I had a fever, not high, but quite high, and so he signed a release. When I went to the mate he thought I’d swum ashore to get a doctor’s certificate: he couldn’t believe a ship’s doctor had done it because they’d had such trouble getting men.’ He didn’t tell the mate that he still couldn’t tie a clove hitch, and if he had been made into a man by his shipboard experience, nobody mentioned it.6

Fifty years later, at the time of his exhibition at the Liverpool Tate in the Albert Dock (by then transformed into a marina and cultural centre), Freud had a letter from Dr Tapissier’s widow saying that he had often told her how good the young Freud’s drawings had been. He was touched. ‘I wrote to her and said that if it hadn’t been for him I’d still be on that ship. I was terribly lucky: within three months of my leaving the merchant pool was formed, so anyone leaving a ship was automatically drafted on to another ship. Before then it wasn’t part of the services. Otherwise I’d have spent the rest of the war at sea.’7

Discharged on 22 May, his ability listed as ‘Good’ (which meant below average) and his general conduct as ‘Very Good’ (ship’s log 132840), Freud left the Baltrover to find Liverpool dramatically altered. ‘Lots of places had gone, just during these months.’ Indeed Liverpool had suffered far more that month than had the convoy. Half the berths in the docks had been destroyed.

Exposure to strafing, violence and extreme cold did not harden Freud appreciably; nor did being pestered and humiliated. He didn’t respond when, sixty years later, a former shipmate invited him to a reunion. ‘The man said, “I wrote to your brother but got short shrift.” Part of the reason for a reunion is to see that everybody has changed more than you, and I’m quite sure I haven’t changed at all. Nor did I want to talk about old times. New times is what I want to talk about.’ He had spent less than three months at sea. ‘It wasn’t long; it just seemed long. It was so unlike my life, it stuck out in a particular way.’ Masefield’s Dauber, bullied and harassed and attempting to prove himself, fell to his death. Freud happened to have survived.

‘I found myself with tears running down my face on the train, back through green landscape: I’d thought I’d never see anything like that again.’

It so happened that the day Freud was discharged Sir Kenneth Clark donned earphones at Broadcasting House in London and declared open an exhibition of ‘British War Art’, selected by himself, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. His brief speech echoed back at him across the Atlantic: words in praise of the ability of Graham Sutherland, Henry Moore and others to express and reflect, as Herbert Read wrote in the catalogue, ‘all the variety and eccentricity of the individual human being’ in time of war. Sutherland’s blitz-damage compositions based on sketches made in Cardiff, Swansea and the East End of London and Moore’s drawings of people sheltering in the Underground like stockpiled maquettes were enlisted in the propaganda push to bring the United States into the war.

Ex-Ordinary Seaman Freud had only a few sketchbook pages to show for his grim escapade, studies of sea, gunner and cook, too scrappy to qualify as the advanced war art that Clark favoured yet in their wariness all the more telling. Over the years, as his seagoing exploits ballooned into legend, questions were asked. How precisely had he obtained his discharge? Was it true that he had murdered the ship’s cook?

What Freud remembered was how sick he had felt. ‘I was terribly ill by the time I got off. My chest had got very bad. I ran a permanent temperature and had to go to hospital.’ He was sent to the Emergency Medical Services Hospital at Ashridge in Hertfordshire, in peacetime the Bonar Law College for Citizenship, but by then taking patients from London, Blitz victims mostly. ‘My throat settled down once my tonsils were out. There were huts in the grounds and beds were wheeled out into the sun. I was so weak that I got caught and the skin peeled off. In the bed next to me was a musician from “Snakehips” Johnson’s Caribbean jazz band whose legs had been broken when the Café de Paris was bombed. The bomb landed bang on the band as they were playing “Oh Johnny”, killing Snakehips. We used to talk about night life and I enjoyed that.

‘My mother came to see me in hospital; it was good because I had such strong sedatives I was asleep when she came.’ In June his parents moved back into St John’s Wood Terrace, thinking perhaps that Lucian should convalesce there and be under supervision; meanwhile Hitler invaded Russia; with that the threat of an invasion of Britain receded. Internees were released and in August Cousin Walter arrived back from Australia, disembarking in Liverpool.

Hospital was a bit like school. ‘This little boy of eleven came across the ward and spat into my face so I gathered all my strength, gave him a bash, passed out and the stitches in my tonsils came open. They kept coming undone: it was quite serious as they were so inflamed, so I was there over a month.’ He left hospital in late July. ‘After a lot of complications, I did some drawings in the ward, one of which is very good I think,’ he told Cedric Morris, assuring him that he would be back in Benton End by the following Friday. ‘I have to wait for my grandmother’s birthday on Thursday; otherwise I’d be down now.’

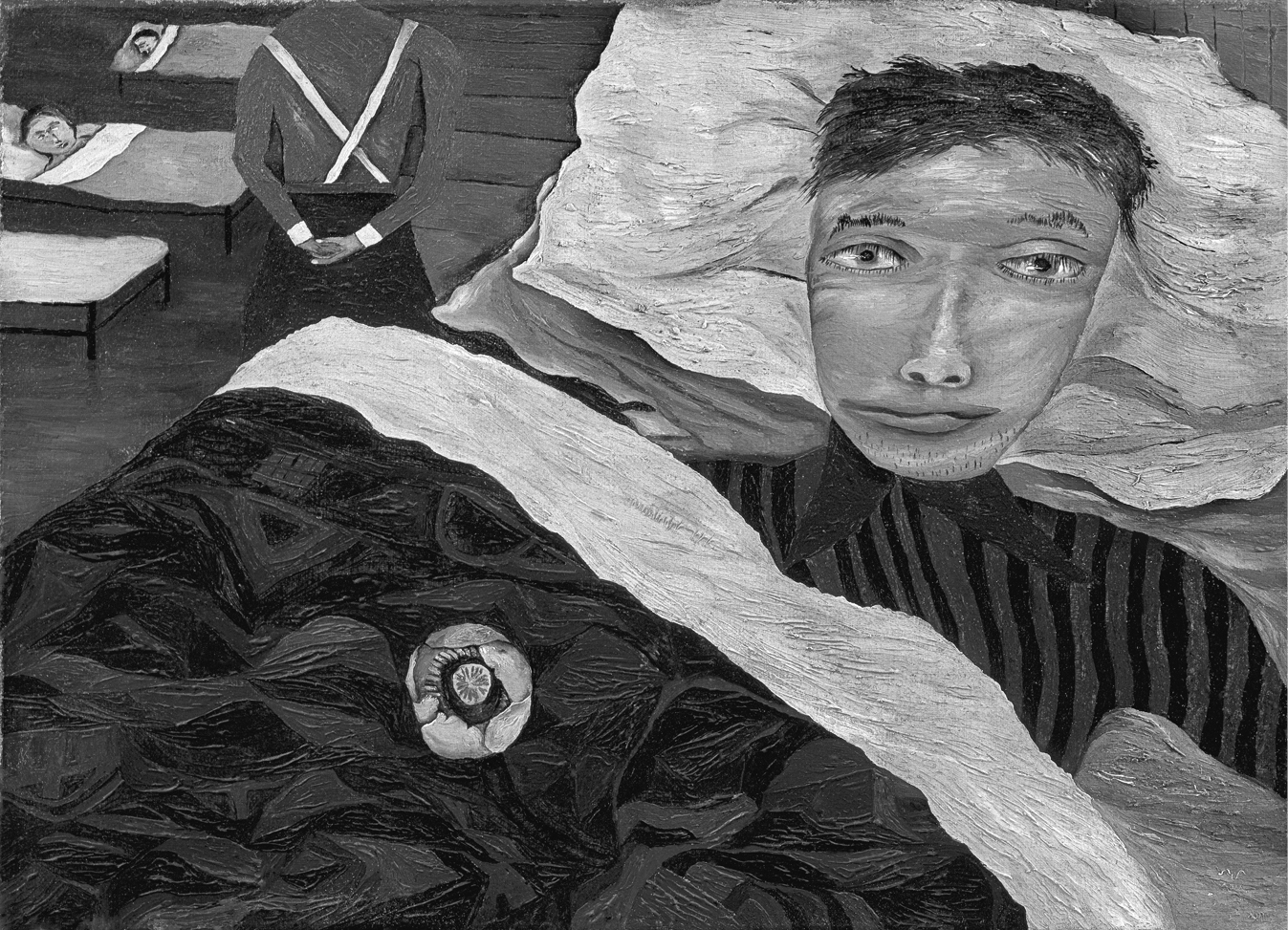

Hospital Ward could be an ex-voto, a thanksgiving in convalescence. ‘Done from memory, except the flower’, Freud explained: patients tucked flat in their beds, a nurse checking for unruliness and a globeflower from Benton End (‘One of those tough slimy things: really beautiful’) laid on the coverlet, a reminder of the Comte de Lautréamont’s image of ‘the child’s face rising slowly above the opened coffin like a lily piercing the water’s surface’. The head resting on the pillow was not particularly the stricken Freud who, he told me, saw the figure as a war-weary soul: specifically Peter Watson with reddened eyelids and stubbled chin chafing under ward discipline.

Hospital Ward, 1941

In another little votive-mannered painting, done around the same time, Watson in open-necked shirt and tight jacket sits holding a tray of what appear to be etching plates featuring a Benton End bestiary: rat, rabbit, horse, dog, chickens, men. Behind him is a bed with a toothbrush laid on it and a view over bleak Nova Scotia in which the Baltrover is sighted offshore, lifeboats slung outboard in readiness for an emergency. A painted rendition of a drawing of a life model startled by the rooster on his knee adds comic alarm to this deployment of Watson as patron saint, a homage designed to flatter and implicate. ‘It was a portrait: the drawing is actually a drawing that existed. I did it in his flat, a crazy queer painting, very personal and like him. I used to always put secrets in. I still do.’

Before going off to sea Freud had asked Watson to write to him in Halifax as he fancied the idea of being met with a letter post restante. Watson obliged. His keen interest was particularly valuable once Freud had become the seafarer returned. His flat in Prince’s Gate was open house where spongers such as the Glaswegian painters the Roberts MacBryde and Colquhoun stayed and where all callers could hang around looking through copies of Verve and Cahiers d’Art and the pictures that replaced those left behind in Paris. Watson wasn’t just the backer of Horizon and the London Gallery, he was everywhere making introductions and quietly exercising patronage. Through him Freud eventually met John Craxton for the first time. ‘Lucian turned up,’ Craxton remembered, ‘wearing a chic brown suit and looking very handsome – he had been in hospital and across the Atlantic since leaving me that note. He had incredible eyes and was very quick witted. He had a fantastic, riveting personality.’8

Charles Fry, a publisher described by John Betjeman as a ‘phallus with a business sense’, asked Freud if he would care to write an account of his voyage for a series of short books that his firm, Batsford, were producing. Fighter Pilot had already appeared. What about Merchant Seaman? No, absolutely not. ‘It would have been a crazy surreal novel.’ He did not want to relive the episode or, for that matter, be taken through it under questioning. Soon after the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 he had a visit from the CID. They asked him about Boeckl, the sailor from Kobe. ‘I thought he’d been caught: he had a grey box and was fiddling with it all the time, and he got very wary when there was talk about wireless. They said, “You realise what we are asking you?”, implying that he was a spy for Japan, which had come into the war by then. They wanted to know where he lived. I knew his girlfriend’s address in Liverpool and didn’t tell them.’