‘Idyllic, in a slightly maddening way’

After months of peripatetic lodging Freud and Caroline Blackwood moved into a flat in Soho with a controlled rent at only thirty shillings a week, previously occupied by Edward Williams, the composer whom Zoe Hicks had married. They paid Williams £1,000 to get it: 86 Dean Street, Soho, a formerly elegant town house owned by Townsends, a firm of builders. ‘It was above a radio shop in St Anne’s Court on the corner of Dean Street, a lovely seventeenth-century house, panelled. It had been a brothel with the rooms divided. Henrietta [Moraes] had been sort of living there. She had a go with Colin [Tennant]; he was a grandee and she was keen on that.’ It was handy for the Gargoyle and the Colony Room.1

‘It was a large room, quite dirty, and had room on the rooftop for drinking. It was not nice, waking in the morning, because it was opposite a synagogue. And the neighbours were neighbourly, which I’ve never liked.’ Their predecessors, Edward Williams and Bill Howell, architect, who had shared the flat since 1948 and kept open house on Sundays, had once heard, Williams said, ‘a peg-legged visitor clumping upstairs at night’ and discovered it was a rat dragging a potato. A young solicitor’s clerk, Jeremy Gordon, sent to serve a writ on Freud for non-payment of rent, remembered him opening the door to him and appearing even more nervous than he. Freud disputed this when I mentioned it to him many years later. ‘Maybe he was delivering something for Townsends, but I feel it’s unlikely that a writ was for the house rent, for a few pounds. It wasn’t a lease – it was on a weekly basis – but we could only be evicted for enormously long non-payment or, obviously, something completely disgraceful.

‘Too many people on the run from the police knew I was there and would ask if they could stay a couple of nights.’

Freud’s range and variety of potential, if not necessarily willing, sitters broadened a little with the move, the prerequisite being that they could spare the time, the snag being that some needed paying.

Joan Rhodes, the strong woman, previously encountered in Madrid, reappeared in Soho. ‘I sometimes took her out to a club or to dance and would take her back to Swiss Cottage where she lived.’ She came upon Freud once having a bath in her dressing room. ‘Didn’t talk about her life: she was with someone quietly for a time. Later on the only people she knew were people she’d known. I said, “Have you ever used your strength for something?” “Once there was a man who was groping me,” she said. “He gave me a push. I got angry and hit him and he went right down and I burst into tears.” Her main thing was tearing telephone books in half. I saw her in music halls; she’d say, with a nice shy smile, “I’m not much good at singing or dancing; not much I can do,” and absent-mindedly pick a phone book off a table say, “Oh dear I can’t find the number,” and rip it in half. In her memoirs, Coming on Strong, she wrote how King Farouk would send for her for birthday parties and she lifted him. Quite a feat.

‘She told me she was having driving lessons and when suddenly the man said, “Put your foot on the brakes” she did, and his head went through the windscreen. “That will do,” he said. I liked her, and she would have sat, but she didn’t quite interest me enough to paint. There are a couple of ink drawings. An amazing thing happened: an offer from Hollywood to be the first female Tarzan. But she had to sign up for seven years and therefore didn’t; I was terrifically impressed. Fame takes a bit longer than the performance. Her parents, who had kicked her out at twelve or thirteen, tried to contact her. She was not ambitious, always put money away and saved it. Later she got a coffee stall outside London somewhere.’

Napier ‘Napper’ Dean Paul, whom Freud knew from Coffee An’ days, came from ‘an ancient family with some spectacular black sheep in’ that had even been mentioned, Freud was pleased to note, in the text to Gustave Doré’s London. (‘One of the family is Dean Paul’: not every inmate of debtors’ prisons, Blanchard Jerrold remarked, is from noble families.) ‘Napper was drunk and druggy, full of hate, and he had quite a lot of inherited money. He would become Sir Brian, when he inherited. He was called “Napper” because he dropped off to sleep all the time, stayed outside cafés and dossed. He used to sell gossip to Patrick Kinross for his column in the Evening Standard. He loathed the lower classes; he said, “Without homosexuality there wouldn’t be a link between lower people and myself. All we have in common is the arse.”

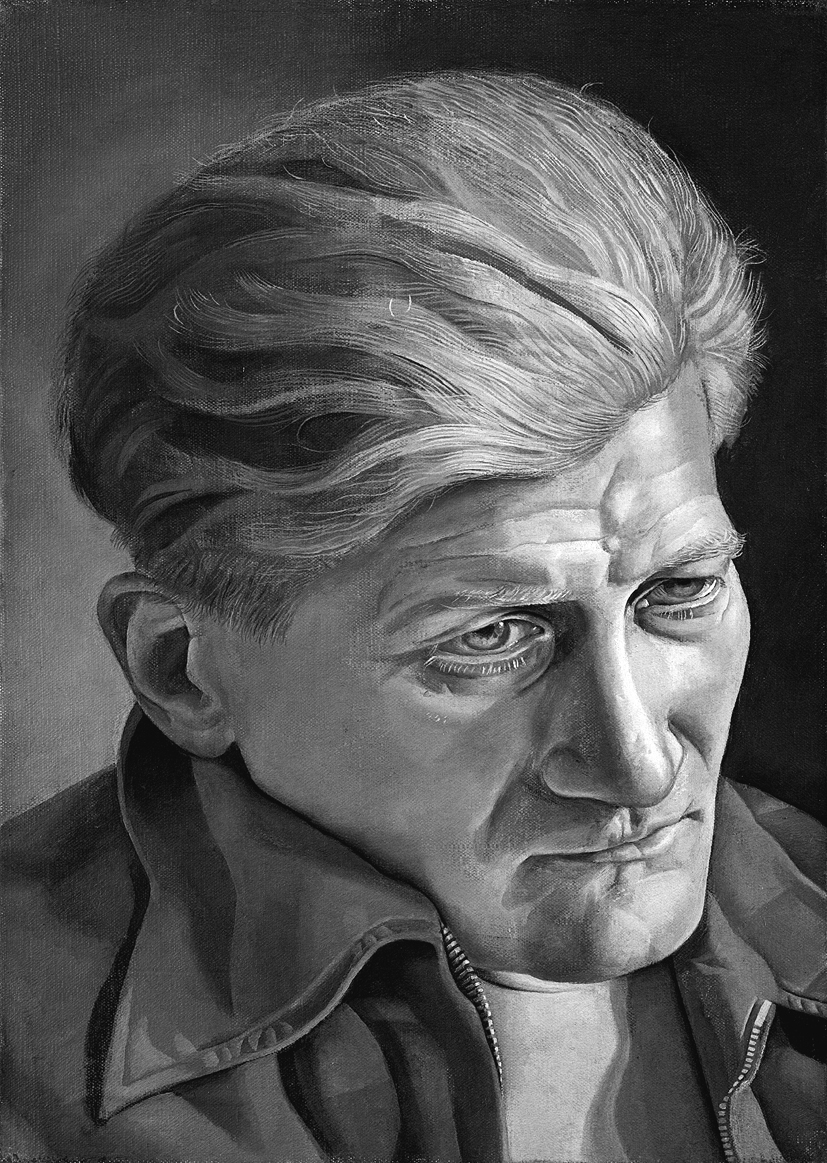

‘Napper’s father was an arrogant upper-class gent who married a Polish musician who was very wilful, loved her children, and didn’t want to deny them the great things in life, so she gave them opium.’ Napper’s sister, Brenda, was an actress who in her heyday had been engaged to Anne Dunn’s uncle, Sir Philip Dunn, and hardly ever worked because of her opium habit. ‘Once – in 1956 – when she was in a private theatre off Leicester Square, in a one-person performance of Firbank’s The Princess Zoubaroff, I took Clarissa [Churchill] to see it and took her backstage after – Clarissa might have been married to Anthony Eden by then – and while we were talking to Brenda she was changing her stockings and her whole thigh was a map of scars, very extreme. More than I’d ever seen, even when I used to go and draw at Rowton House and in shelters under Charing Cross.’ The portrait of Napper [Portrait of a Man, 1954] breathes grievance. ‘It’s very like,’ Freud commented. ‘He’s in a misery position, in a zip-fronted jacket, almost exhausted. It’s before my discovery of Naples Yellow.’ Sour-faced in mustard and grey, an Old Etonian down and out and feeling his age – he was in his fifties – is as Orwellian as you could get. ‘I paid him to sit. I was working at the Slade then and they had a staff show and I put it in and people loathed it; I was conscious of that Winsor & Newton texture of canvas which I loathe too.’ Afterwards he sent the painting to Andras Kalman’s gallery in Manchester where it sold for £50.

Portrait of a Man (‘Napper’ Dean Paul), 1954

As a rule Freud did not identify his sitters in the titles of paintings. ‘The reason for not naming is to do with discretion, chiefly protecting people, not bothering people who are alive.’ To name fellow painters such as Bacon and Minton ‘seemed relevant’, he said. ‘Because they did something.’ Other portraits were given descriptive titles. Man in a Headscarf for example was initially called The Procurer. ‘And it was quite a bit bigger. I used to have a lot cut down. The paint went on over the edge so to make sure I put undercoating on to prevent anyone painting over.’ He cropped it to pressurise the furtive air of a portrait that involves both an assumed and a mistaken identity.

Man in a Headscarf (The Procurer, aka David Litvinoff), 1954

‘I was in a club in Wilton Place where there used to be a theatre and the Berkeley Hotel now stands: Esmeralda’s Barn. I was taken there – never been in there before – and it was very lively, full of exciting people like the very young Mary Quant and lots of rather grand girls. And as I went to the bar I heard the barman say, “Is that on your bill, Mr Freud?” and the person said yes, and I looked and I saw what was, I thought, the most repulsive person I had ever seen in my life. When I got to the bar I said, “Excuse me, who was that just buying a drink?” and he said, “Oh, that’s Mr Lucian Freud.” So I said, “Oh, thanks.” So then, understandably, I took some trouble – though none was needed – to get to know this horrible man. And I thought, well, I can do a self-portrait without all the bother of looking in the mirror.’

The Procurer, shrouded with a scarf like a suspect bundled from a police van, was David Litvinoff. ‘Which wasn’t his name either. He could be funny. Walking along, he’d say, “Did you see the photograph of Mussolini and Claretta hanging from a lamp post?” and, chin up, he’d do the pose of both of them. He was always trying it on. He spoke rapidly and excoriatingly, lived without possessions and with a degree of fearlessness. He walked into St James’s Club in Piccadilly, waited, saw an old gent reaching up for his coat and helped him into it. “Extremely kind,” said the old gent. “Anything to help a fellow Jew,” he said.

‘Everything about him was fake,’ Freud reckoned. ‘“Isn’t there anything straight about you?” I asked. “Even your name is false.” “What do you mean?” he said. “Who told you that?”

‘Levy he was really called. His mother had married a Litvinoff. His half-brother was Emmanuel Litvinoff the writer. He worked for [Peter] Rachman as a rent collector and then for the Kray twins, a wrong move and real trouble as he kept procuring girls for Ronnie. Then he procured people to do with the film Performance2 and supplied lines of criminal argot such as “Puttin’ the frighteners on flash little twerps”.’

‘David was the whole film,’ the film historian David Thomson said. ‘He knew the Krays. Very naughty boys who’d cut you up with a sword. And so David was the catalyst – he just brought the whole thing together. And that’s why David gets a credit on the picture as dialogue coach and technical adviser. And well deserved.’3

Freud suspected that Litvinoff had been a boyfriend of Ronnie Kray; certainly he lived hazardously. ‘He talked and talked and was sarcastic,’ Auerbach remembered. ‘So much so that the Krays threatened to slit his tongue, it was said.’4 When George Melly gave a lecture on ‘Erotic Imagery in the Blues’ at the ICA, Litvinoff put his hand up and asked if it was permitted for members of the audience to wank. Melly hailed him ‘a dandy of squalor, a face either beautiful or ugly, I could never decide which, but certainly one hundred percent Jewish, a self-propelled catalyst who didn’t mind getting hurt as long as he made something happen, a sacred monster, first class’.5 His tirades were famous for their unstoppable venom and flow.

The vicarious self-portrait went ahead until Freud decided that Litvinoff’s outrageous carry-on was too much for him. ‘Every time he came round he brought girls along and I used to mock him about it. Procuring gives people strange pleasure; it’s actually a sexual thing and it was absolutely maddening. Once he brought a girl I really liked and I made a date with her behind his back. Anyway, it was impossible for him not to procure and I have a terrible snobbery about being procured for: I like the illusion of romantic meeting – chance or something – not the idea of this awful, unasked-for service.

‘I said to him, “I’d like to call this picture The Procurer, but, knowing what you are like and I don’t want any trouble …” (He told me he did not even trust himself not to sue.) I got him to give me a statement. So he wrote me a note saying he wouldn’t sue me and then did. He went to the newspapers but he couldn’t do anything because I had this letter.’ Thinking back, Auerbach suspected that Freud himself thought The Procurer would make good copy and that news of a possible lawsuit could provoke advance interest in his show at the Marlborough Gallery in 1958, much as Sickert had won headlines with eye-catching titles like The Camden Town Murder. Consequently the William Hickey column in the Daily Express of 25 March that year featured the painting together with mugshots of the two of them side by side and a report of Freud’s ‘smart Bond-street opening’ in which Litvinoff (‘independent, and one of the smart Chelsea set’) featured as a wronged innocent, his flow of contributions to the Express as a William Hickey stringer going unmentioned. ‘Mr Litvinoff, who was not at last night’s preview, used to be Mr Freud’s secretary. Mr Freud’s painting of him was originally to be called “Portrait of a Jew”.’

One Easter weekend several years later Litvinoff answered the door at his High Street Kensington flat only to be punched in the face and have his head shaved after which, tied to a chair, he said, he was hung out over a balcony, regaining consciousness to the sound of ban-the-bomb Aldermaston marchers passing below singing ‘Corrina, Corinna’. True to form Litvinoff, whose accounts of this ducking-stool outrage varied from telling to telling, let it be implied that it could well have been Freud who had set the presumed heavies on to him. Freud always liked the idea that he could deal with problems by threat, direct or directed, but this incident, so swiftly elevated into legend, smacks more of Kray reaction, say, than Freud over-reaction.6

‘My dealings with him weren’t for very long. Michael Astor had the painting: he thought The Procurer was improper and retitled it. Litvinoff killed himself later.’7

Accusations and counter-accusations propelled gleeful if exasperated legend. Ten years after it had last served him as a motif, and shortly after Cecil Beaton photographed little Annie playing with it on the landing at Delamere Terrace, Freud lost his zebra head. ‘I had it a long time and then in the end I had it outside my room as you walked up the stairs and David Litvinoff or somebody took it. It was a bit tiresome and quite heavy. The impetus of theft would give extra strength.’

In his Romanes Lecture on ‘Moments of Vision’, delivered in May 1954, Kenneth Clark examined the phenomenon of sudden insight. ‘We can all remember those flashes when the object at which we are gazing seems to detach itself from the habitual flux of impressions and becomes intensely clear and important to us.’ Clark singled out Graham Sutherland as someone good at spotting such moments of vision, when things ‘will suddenly detach themselves and demand a separate existence. His imitators think that they can achieve the same effect by going straight to the thorn bush and painting its portrait; but it remains inert and confused, like any other casual sitter.’8 In other words Neo-Romanticism, or whatever one chose to call the inky excesses of the previous decade, was now dead. No more thorn-girt coves.

Accordingly, Lawrence Alloway told the mainly American readers of Artnews in November 1954 that there was a ‘terrible casualness’ in Bryan Robertson’s choice of ‘British Painting and Sculpture 1954’ at the Whitechapel Art Gallery. His omission of Nicholson, Sutherland and Bacon – and Freud – was deliberate, it could be assumed; not so his parade of what Alloway took to be ‘evidence of the collapse of artists who developed in the 1940s’. That generation, he argued, had exhausted themselves. ‘Colquhoun and MacBryde seem to have painted themselves out, John Minton is no longer able to hold apart his fine art and his commercial art styles and John Craxton’s lyrical glimmer has gone out, behind tedious and inflated Ghika-like patterning.’ The prevailing style was ‘still rather Festival of Britain – spindly, whimsical and bright’.9 Alloway was the coming critic associated with the Institute of Contemporary Arts, tuned into the urban, the progressive, the colourful and the consumerist; David Sylvester, by contrast spoke up for a more seasoned Realism, reflecting not the allure of things American but the shortcomings of a penny-plain Britain. The time had come, he sensed, for a new movement to be identified and labelled by someone such as himself. Stung to barracking cynicism, John Minton, writing in Ark, the Royal College student magazine, coined the term ‘pre-Sylvestration’ for ‘the period before one’s ideas were pinched by David Sylvester and the bandwagons rolled on’.10

In the December issue of Encounter Sylvester came close to deploring the dingy tonal look yet inadvertently helped give it currency by remarking that the painters dumped everything they had in their pictures, including the kitchen sink. ‘The dreary greys and browns of the pictures and their general air of depression had little to do with the observation of working-class life as it is, but were the products of a sentimental preoccupation about working-class life.’11

Typical of what caught on as the Kitchen Sink School was Jack Smith’s Child Walking with Check Tablecloth (1953), a domestic scene featuring brown lino and nappies strung up to dry. Smith protested at the label and later repudiated what was, to him, a novice’s straitened phase. ‘I didn’t find a language to suit my imaginative needs until the early 1960s.’ He particularly resented being assigned a role in the class struggle: ‘I don’t identify with any class. The artist is classless and any identification of that kind is creative death.’12 Rising above such concerns he later devoted himself to abstract scintillations. However, in the years when Jim Dixon, Kingsley Amis’ Lucky Jim, became a byword for cheerful truculence, many took Smith and others to be similarly motivated, railing in their duffel coats against the intrusion of chic Parisian miserabilism and Yank Abstract Expressionism. Lavish spreads of household goods cluttered John Bratby’s tabletops: packets of cornflakes and canisters of Vim lumped together hugger mugger in profane emulation of seventeenth-century Dutch still lives, motor scooters parked in the hallway, Mrs Bratby driven mad and he himself in horn-rimmed specs squinting through cigarette smoke at his own chaotic profusion.

The place to see Kitchen Sink painting was the Beaux Arts Gallery in Bruton Place, a former mews off Bond Street, run by Sickert’s sister-in-law, Helen Lessore, who had taken over when her husband died in 1951. She showed Bacon in 1953, John Bratby in 1954, Frank Auerbach in 1956, Leon Kossoff in 1957, Michael Andrews in 1958 and other Slade graduates, such as Euan Uglow, Craigie Aitchison and Jack Smith. Having bought and sold Nicholas de Staels in order to pay Smith’s stipend she then dismissed him for producing work she considered ‘non-realist’.13 She had strong views on the canon of Realism. Bratby startled her with his output and for a while she welcomed it. He painted, she declared, ‘with almost incredible speed, with something like the torrential passion of Balzac’.14 No Balzac he: his novels, a sideline, were as headstrong as his pictures and as indiscriminate. With what she came to regard as ‘stupidity and arrogance’ he told her in 1960 that he planned to stop painting completely to give his pictures rarity value. In 1958 he was the obvious choice when someone had to be found to supply turbulent Gulley Jimsons for a film version of Joyce Cary’s novel The Horse’s Mouth. Already by then this Angry Young Painting phase was obsolete. The Kitchen Sink fad irritated Freud. Not least, he admitted, because Sylvester had supplied the label. ‘I felt none of it was especially good. It was obsessive in a rather mindless way. Especially Bratby. I knew it was knitting.’

In late 1954 Ernest Brown of the Leicester Galleries invited Freud to exhibit in his annual New Year show, ‘Artists of Fame and Promise’, the thought being that, following Venice, his fame was as great as his promise had been ten years before. It was agreed that the four paintings of Caroline were to be shown; agreed that is until the possibility arose of winning a sizeable amount of prize money.

The possibility was complicated. A South African con man, LeRoux Smith LeRoux, who had recently left the Tate – where he had been Deputy Director – having waged a vicious campaign with Douglas Cooper to dislodge the Director, John Rothenstein, had immediately – on Graham Sutherland’s recommendation – secured a job with Lord Beaverbrook buying paintings for him and organising a Daily Express Young Artists competition and exhibition to be held at the New Burlington Galleries in April 1955. Freud had nothing more suitable than Hotel Bedroom to enter for the competition but had already promised it to the Leicester Galleries along with the other Caroline paintings. He decided that he would have to have some assurance from LeRoux that he was likely to win. ‘“Unless you can guarantee a prize,” I said, “I won’t enter.” “I think I can guarantee you’ll get one of the prizes,” he said.’

Trust LeRoux Smith LeRoux? In the circumstances it seemed a safe bet and Freud decided to pull out of ‘Artists of Fame and Promise’. ‘A letter came from Mr Brown and he was very angry. “We are used to dealing with English artists who keep their word,” he said.’

With or without the LeRoux guarantee, Hotel Bedroom was an obvious potential winner. Like Interior in Paddington in 1951, it stood out as different. If in Venice it had gone more or less unnoticed, in the New Burlington Galleries it stood to appear more focused and more testing than anything else submitted. ‘Being done for a competition meant aimed rather than painted; the reason to work in that tiny detail way was that it had to be substantial.’ In the end ‘that tiny detail way’ proved substantial yet stifling.

The judges, Sutherland, Herbert Read, Anthony Blunt and LeRoux, deliberated. Freud was awarded a second prize, of £300. ‘I had an odd note from Graham Sutherland. “We wanted to give you first prize but it had to go to an unknown.”’

Two unknowns in fact each received the first prize £750: Bryan Kneale from the Isle of Man, brother of Nigel Kneale (the creator of Quatermass, television’s first documentary-style sci-fi drama), and Geoffrey Banks from Wakefield, for his painting Street Scene with Tram. A £100 prize went to Edward Middleditch, for Dead Chicken in a Stream. ‘No responsible painting master in any art school would agree with the award of the two first prizes,’ John Berger commented in the New Statesman. ‘The exhibition as a whole is of a low standard, full of easy tricks.’15 He didn’t mention Freud who felt cheated somewhat. ‘It was a completely crooked prize: I got this money but they said they’d have to take the picture. “You are very lucky,” they said. “The prize goes to New Brunswick.” Beaverbrook was setting up his collection there. I’d have got £400 otherwise, if I’d sold it.’ Two of the portrait heads of Caroline were also on show, priced at £180 and £100.

The Express declared Hotel Bedroom a mystery picture (‘What does it mean? What is the human story behind it? That is what people long to know …’) and speculated about what the ‘33-year-old grandson of Sigmund Freud’ was up to in the picture, so glum for some reason. ‘Why has Freud painted himself and his wife as if they were overcome by sadness or had had a quarrel? That is their private affair.’16

The reaction to the news along Delamere Terrace was one of astonishment. A telegram always meant bad news but this one was different. Lu the painter had done it again. ‘When I got a telegram when I won the Daily Express competition, they were amazed. “I hear you had it off,” they said. In Delamere, when pictures were stolen, whatever they were – photos they called pictures – they would ask me to look at it. “It come out of a good home,” they’d say, meaning a doctor’s house.’

Frank Auerbach remembered Freud telling him that becoming a painter was for him the alternative to ‘going up the ladder’, that’s to say burgling.17

In June 1955 Stephen Spender went to a party at Ann Fleming’s where, he noted in his journal,

there were Lucian and Caroline Freud. This began a bit stiffly, Lucian obviously being embarrassed by the presence of John Craxton and myself, towards both of whom he has behaved rather badly. He was wearing a bottle green suit, and as Cyril [Connolly] remarked afterwards, one noticed what an extraordinary rise has taken place in his life since we first knew him. Formerly he was bohemian and poor, now he has a car costing £3,000 and is married to an heiress, has danced with Princess Margaret, is always in the gossip columns and is an expensive and fashionable painter. In spite of his large income he does not seem to trouble to pay debts incurred to his friends before he was so fortunate. He always makes faces, talks for effect, but on this particular evening, he was rather ineffective.18

Caroline Freud wasn’t good company, Spender added later: ‘She seems never to introduce a topic of conversation on her own initiative. This seems characteristic of a whole class of girls whom Lucian, Cyril and their friends fall in love with.’19

The following month, when Spender found himself at a Freud party in the Dean Street house, he noted that the place looked unoccupied almost: shiny white paint, not much furniture and huge ‘Chinese’-looking objects for decor. Freud told him that he had given Colin Anderson the Freud–Schuster Book and then, to his surprise, recited some of the poems that had been his contribution to it, ballads mostly. Undecided whether to be touched by this or irked, Spender could only think that there was after all a bond of sorts between them. ‘I have this feeling of invincible ménage with Lucian, and also with Cyril. A kind of secret relationship which may last throughout life.’20

A quarter of a century later a note from Freud to Spender went some way towards acknowledging this:

Dear Steve, Yes – Cyril was rather dishonest, but then, your behaviour was often far from honourable – as for me, I was extremely devious. I hope your mind’s not wandering.

Love Lucian.21

The tension so clearly displayed in Hotel Bedroom had persisted. Being together was a strain and the urban life, strung between studio and Soho, never eased. ‘Things were quite hard for Caroline in London and I had this idea that being in the country would be better for her. She was nervous and she wasn’t very well.’

House-hunting began. ‘We were looking round for somewhere and stayed with a girl who had been at school with Caroline and her husband, who lived in a house that had been [William] Beckford’s Fonthill.’ Clare Barclay, married to James Morrison, horse-breeder, felt that Freud was keen, all too keen, on being the country gentleman. She recollected the arrival of Caroline’s horses from Ireland some time later and one of them escaping on Tisbury station. Freud’s memory was more of his efforts to restrain and calm it, and the further mishap that resulted. ‘A grey filly, two years old, and it panicked being unloaded and slightly hurt itself. I was up with it all night and the next morning went to the station to see it and suddenly I went to sleep. The Alvis – rather a fast car – went off the road, turned over, and back on its wheels again. Lucky. Thank God nobody knew. Incredibly lucky, I felt, and the nearest thing to feeling ashamed.’

The house they decided upon, Coombe Priory on the Dorset–Wiltshire border, secluded in its valley bottom, was not excessively large, and not too far from London. Being on the Arundel estate owned by the Roman Catholic Dukes of Norfolk, it had once served as a refuge for Cistercian monks escaping the French Revolution. ‘“Priory” is a nickname: it’s a seventeenth-century farmhouse with a supposed secret passage to the abbey at Shaftesbury.’ If that connection was far-fetched, Shaftesbury being several miles away, there were firmer rumours of a priest hole behind the drawing-room fireplace. The kitchen had a well in the floor and, Freud remembered, a sixteenth-century closed stove.

Unlike Balthus, who in 1954 bought the Château de Chassy in Bourgogne in fulfilment of his desire to be an aristocrat among artists, Freud had no great appetite for landownership, though undoubtedly – yet briefly – Coombe was for him a throwback to Gross Gaglow, Cottbus. Initially he enjoyed improving the place. ‘Coombe was idyllic, in a slightly maddening way: when you got down to the bottom of the lane you suddenly hit this idyllic end. I planted a lot there and there were some stables and a yard and a small park which was lovely, leading up to a girls’ school (one didn’t see them), trees all around and Austrian oak, sycamore, beech, lime, one of each alternately all along, light and dark, catalpas too (heart-shaped leaves). I had an idea that Caroline would be happy there and didn’t think that her unhappiness was to do with me racketing about so much. She didn’t like being alone, in the circumstances.’

The house was long and narrow with stone balls on the gateposts and assertive gables. There was fleeting pleasure to be had, Freud found, arranging impressive furniture in the three rooms on the ground floor and, that first spring, placing daffodils one by one in jam jars on the stairs. He also began painting a cyclamen mural in the dining room.22 Spanish carpets were flown in for them by Caroline’s former employer, in his private plane.

Ernst Freud advised Caroline on improvements: a new staircase, restoration of the attics and a studio of sorts. ‘Caroline and my father went down to do the house and they met John Betjeman on the train (he had been fond of Caroline’s father) and he said to Caroline, “What big eyes you’ve got. Doesn’t it hurt?” Caroline let me build on a kind of studio shed just outside the kitchen door.’

Not having anticipated the social obligations that went with country-house ownership, Freud became fretful. ‘People left cards and they were angry as we didn’t return their calls. Lord Croft or something. It seemed awfully interesting in London, going into very odd houses and flats and rooms, but in the country it was limited, very limited.’ Tim Nicholson remembered his mother EQ taking him and his sister as teenagers to renew acquaintance. It was not a success. ‘We called in one afternoon on spec: I remember how overshadowed the place was: dark and claustrophobic.’ Cecil Beaton, living two valleys away at Broadchalke, brought his mother to see the Freuds in their ‘new grey stone house’.23 He photographed them in the drawing room, innocent occupants but with a Bacon on the wall behind them flagging up unconventional tastes. A new, as yet unused, easel was to be seen. In some shots Beaton put Caroline in the background, complicit, mischievous even. Then he photographed Freud solo, posed with near-life-size bronze stags, with bay trees in tubs and with the cyclamen mural, three leaves and a single bloom (which is as far as it ever got) haloing his head like flying laurels. As it filled with acquisitions, a mansion complete with aviary, the house became reminiscent of Clandeboye where the hallways were replete with massive Indian Raj relics. Chessboard table, buttoned sofa, converted oil lamp and Empire chairs: these were all too obviously set dressings for Beaton portrait sessions. In which, lastly, Freud wore military dress trousers with a stripe down the side. It seemed he was emulating Clandeboye taste from days of yore.

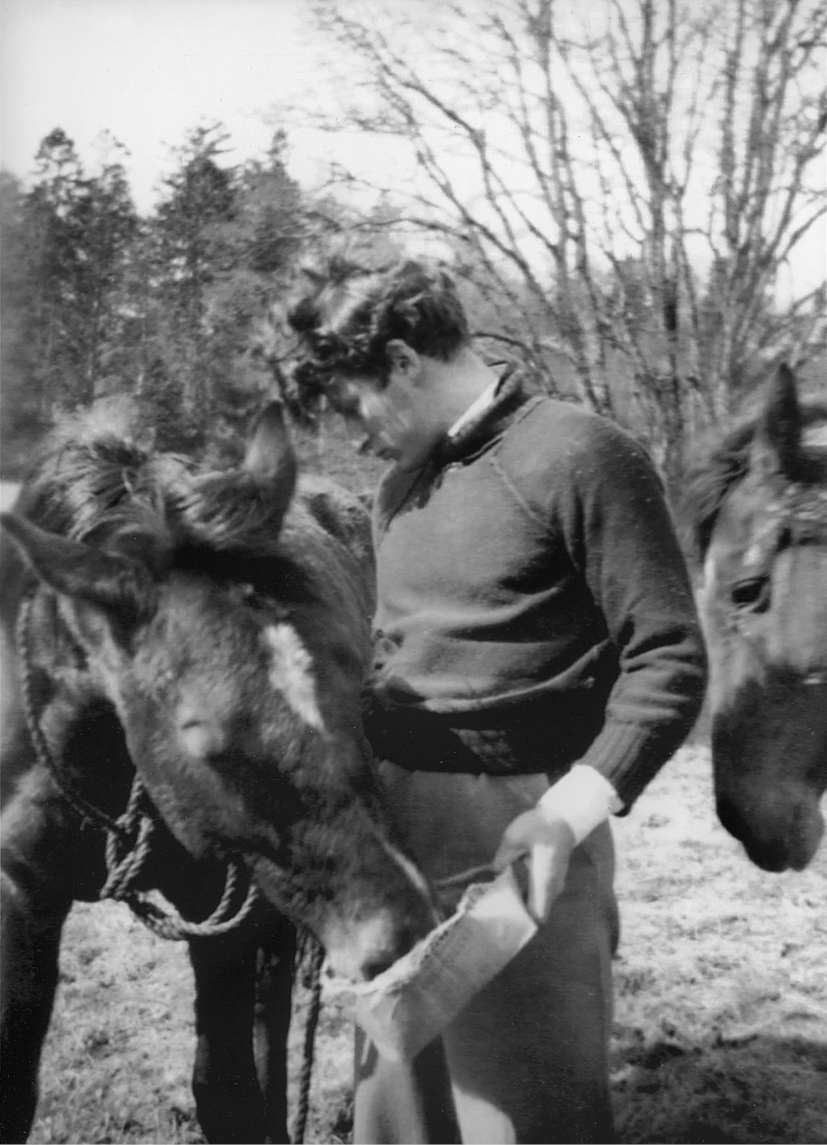

The house, complete with housekeeper, was too ordered for him. He couldn’t settle. ‘I drove down from London in the Alvis, once twice in one day. I was never there for more than a day or two at a time. I liked planting trees and I liked the idea of the horses – I always loved fields and horses – but not the idyll aspect. Nights were difficult. I rode at night a lot.

Lucian Freud at Coombe Priory, Dorset c.1957

‘After dark we used to go to a drinking club in Blandford Forum, not far from Bryanston, in the gatehouse of a Vanbrugh house – at Tarrant Gunville – where a queer called Farquharson lived: not many there, women in trousers. Lady Julia Duff’s queer companion Simon Fleet, who helped Beaton, and Rattigan with his plays, and drank an awful lot, gave me a membership of the club.’

Coombe became little more than a weekend place for Freud where, needing company, he could entertain. Peter Watson came down, also Charlie Lumley (‘Me and Lu used to drive down in the car’)24 and Michael Wishart and Ted, a Delamere neighbour, of whose safe-breaking skills Freud was not yet aware, and also Caroline’s admirers Cyril Connolly and David Sylvester. ‘Cyril and Sylv were courtiers.’ Two Bryanston boys, connections of Caroline’s, came for tea. ‘I did a horrible thing to Sylv. Caroline made a huge cake and Sylv took three-quarters of it and the boys’ faces fell and I said, “I refer you to Mr Sylvester if you want cake,” and he went red. Terribly unfair.’

When Michael Andrews, ex-Slade student and by then a friend, was there he promptly busied himself painting a tree in the garden and drawing Caroline’s shoes left on the doorstep; he was conscious of the two little daughters being around and the housekeeper being ‘very weepy and sniffy, as Lucian had behaved atrociously to “poor Lady Caroline”’.25 Freud drew Annie with a soft toy, but never managed to work much there. As for Annie, she found staying at Coombe uncomfortable: ‘I remember there being lots of strange furnishing things in their entrance hall: circus carousel horses, carpets in weird colours. The strangest memory there: Caroline’s mother had sent her a black velvet matador outfit with sequins on and they decided sequins were disgusting and they sat there together giggling and snipped off the sequins.’ It was, Annie thought, no place for real children, namely herself and Annabel. ‘Caroline was young and gaga. Annabel was sleepwalking and sick. A nurse or the au pair came once or twice with us, but this time we were on our own and Caroline was useless.’26

The nearest thing to an unconventional stimulus was the Augustus John household fifteen miles away. Freud went over to Fordingbridge a few times to see the aged doyen of British painters at Fryern Court. ‘When I went for a meal I’d hear roaring sounds of fury and frustration from his studio in the garden where he had a painting he had been working on for years, an awful huge thing. (It went to Dowager Lady Melchett; she had been fast and pretty and was, I think, still carrying on with the window cleaner and people doing up her flat off Sloane Square.)’ Once, just the once, he drove Augustus John up to London. ‘Dodo [Dorelia John] said, “Stop every now and then and get a drink at a pub,” so we did and in one pub they said, “Would your father like another one?” He was furious. He couldn’t hear very well and was very funny and melancholy. He talked about speaking Romany: “There’s not many Romany-speakers left. Nor many Romanies.” He was very lame: he’d fallen out of a tree chasing a girl.

‘We had dinner in Sloane Square, the Queen’s Restaurant, quite dingy. “Tell me, do you think I’m on my last legs?” he asked as we were walking to this restaurant. It was raining and he said, “Let’s dodge the drops” – old-fashioned words – and pulled me into a shop doorway. He was certainly likeable. I think that he was heroic. He and Epstein were forgotten, in a sense; Ep was making money but he was hardly doing anything. Dodo was terribly good to all the children.’

A night on the town with Augustus John was still a possibility. ‘This girl, she was a burglar from Chelsea, an illiterate sort of one that people with car showrooms used to hire to savage rivals; I didn’t draw her, only saw her a few times, didn’t know where she lived. But after I saw Augustus he said, “This girl keeps ringing, asking where you are.” She was quite exciting: semi-gypsy, living in Chelsea, doing all kinds of guilty things.’

Soon afterwards Freud handed Spender an article that Augustus John had given him. Would he care to publish it in Encounter?

Samuel Beckett, writing on Jack Yeats in Les Lettres nouvelles, said ‘The artist who stakes his being comes from nowhere and has no brothers.’27

‘Magnificent at night the view of floodlit Battersea Power Station from the bar,’ the Architectural Review guide London Night and Day, published in the early fifties, said of the Royal Court Theatre Club in Sloane Square. ‘The inspiration of [Clement] Freud whose witty news letters are worth reading in their own right.’ It was a dinner-dance venue and it became the scene of yet another Freud-on-Freud conflict.

‘I found that, having been amused, quite, by his servility and “sweet” manner, he became cloying and ghastly. Beckford had a person called “Kitty” Courtney, Lord Courtney, whom he persecuted. I felt that my turning against him was almost physical. When he stopped being a waiter there was a time when Clement ran the Royal Court Theatre Club above the theatre and I was turned out of it for being improperly dressed (no tie). He said there was royalty present, which would have been Princess Margaret and Rory McEwen in tartan. He would play and she would sing. I wrote to him:

Dear Cle,

We are told not to trust appearance and to look beyond them for the real depth and value of the nature of the person. But in your case, try as I might, I cannot avoid concluding that you are a prize cunt.28

Clement’s recollection was that Lucian had come to the club to borrow money off him. It was, he said, ‘Lucian’s last social call on me’.29

Another incident that forever festered was the occasion, some time earlier, when the brothers raced along Piccadilly and Clement, falling behind, shouted ‘Stop, thief!’ Hideous discomfiture. Clement used to claim that Lucian was the one who shouted. Either way, there was enmity and a brandishing of long-held grudges.

‘Early in the war Clement had a girlfriend. I read a letter from him that he’d left around about a visit somewhere, saying they had rather nice pictures: “Not Lucian’s kind”.’ Around then, their cousin Wolf Mosse remembered with incredulity, he heard the brothers in the road discussing the girls they had had. Lucian thought this an exaggeration. ‘I think I once went with a girl who said she’d been with him,’ he told me. ‘A girl from Trinidad, very simple.

There was a rivalry in his head: appropriating them mentally. I said to my mother, “Why’s he so awful?” “It’s entirely your fault,” she said. “Because you bullied him so much.”’ He asked her if she could think of any precedent for Clement in the family. ‘She said, “Yes, there’s a great-uncle who had a similar personality.” When the Kaiser decided to tax the population he sent round to find out everyone’s earnings and he, being what he was, gave a most enormous sum for his income, had a huge tax demand and thereupon killed himself.

‘A conversation I had with Sylv long ago. He raised his eyebrows in misery. “I’m often taken for your brother,” he said. “I’m not,” I said.’