“The Social Scientists Make a Huge Contribution”

Following World War I the U.S. government had shut down its propaganda and foreign intelligence agencies within months after signing the Treaty of Versailles. After World War II, by contrast, the Truman and Eisenhower administrations institutionalized these agencies and encouraged them to acquire sweeping powers. This policy had considerable implications for the social sciences in the United States, because the leaders of these agencies frequently considered the social sciences essential to their missions.

At the same time, the meaning of the term “psychological warfare” evolved in important ways that are outlined in this chapter. During World War II, the United States had been unambiguously committed to a declared war against a clear enemy, and psychological warfare had contributed to that struggle. Postwar conflicts were considerably different: war had not been “declared” in any traditional form, even in the long battles in Korea and Vietnam; the front lines, disputed territories, and even the enemy were almost always hazy; and each major international faction regularly deceived its own population and the world at large concerning how and why the contests were fought.

Within that context, concepts like “psychological warfare” and “psychological operations” acquired new layers of euphemistic explanations and cover stories. As will be seen, these myths permitted national governments to pursue covert political operations abroad, and even fight medium-scale wars, while at the same time evading virtually all oversight and accountability for what they were doing. Most U.S. social scientists, like most Americans generally, were kept well out of the loop when the national security apparatchiks made decisions.

But there were exceptions. For those scientists with the connections and insights necessary to refine U.S. government tactics for pursuing purported American interests abroad, the ambiguity of the cold war offered significant professional opportunities. For the first time in peacetime, the U.S. government was an eager customer for some types of social science expertise, particularly concerning foreign countries. This was especially true of the rapidly growing U.S. intelligence community.

“In all of the intelligence that enters into waging of war soundly and the waging of peace soundly, it is the social scientists who make a huge contribution,” Brigadier General John Magruder of the OSS testified during Senate hearings in early November 1945.1 Political, economic, geographic, and psychological factors were of “extraordinary importance” to the overall postwar intelligence effort, he insisted, adding that

the government of the United States would be well advised to do all in its power to promote the development of knowledge in the field of social sciences.… Were we to develop a dearth of social scientists, all national intelligence agencies servicing policy makers in peace or war would be directly handicapped.… [R]esearch of social scientists [is] indispensable to the sound development of national intelligence in peace and war.2

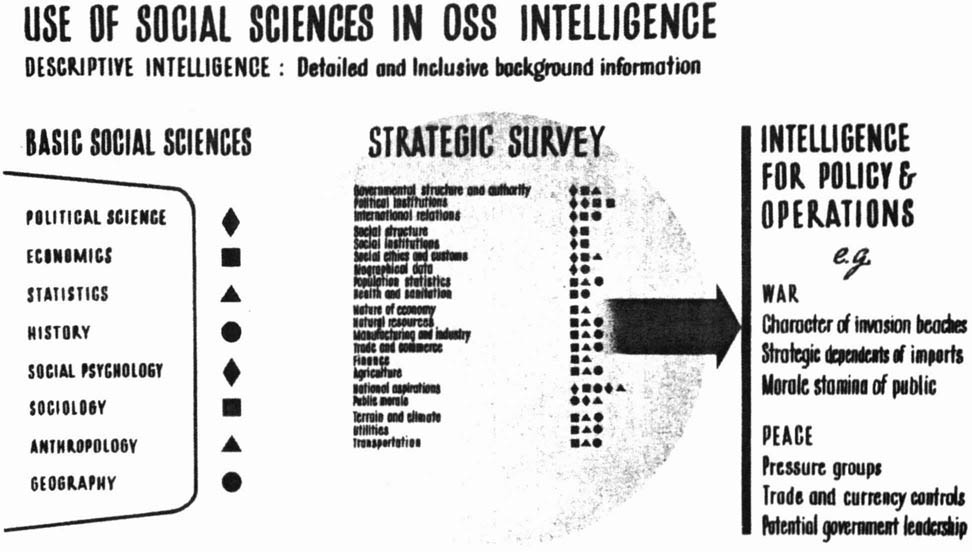

Magruder introduced a chart into the Senate record illustrating the OSS leadership’s perspective, which is revealing on at least two counts (see Figure 1). In the OSS leadership’s view, wartime and peacetime operations formed a clear continuum. While different tactics could be employed as situations changed, the intelligence community’s fundamental perspective remained that U.S. interests could be best achieved by dominating rival powers, regardless of whether the United States was technically at peace or at war at any given time.3 Magruder saw peaceful engineering of consent for U.S. aims as desirable when it worked, but the option of using violence to achieve national goals remained essential. Moreover, as Figure 1 illustrates, the OSS also believed that virtually every aspect of postwar intelligence operations should employ sociology, social psychology, or both.

OFFICE OF STRATEGIC SERVICES

Despite the OSS leadership’s ambitions, however, the shift from hot war to cold war—and the institutionalization of communication studies that came in its wake—proceeded in fits and starts after 1945. OSS chief Donovan had long been a favorite of Franklin Roosevelt, but he was mistrusted by Roosevelt’s successor, Harry S Truman, and by many in the U.S. Congress. Truman ordered the OSS dissolved in late 1945 and transferred most of its intelligence collection and psychological warfare staff to the Department of State.4

A second important World War II psychological warfare agency, the OWI, had already been dismantled by Republicans in Congress, who had concluded that OWI’s propaganda in the United States had provided de facto support for Roosevelt’s 1944 reelection drive by praising his leadership in the war. A number of southern Democrats on Capitol Hill had also been offended by OWI’s promotion of racial integration in the army and in war plants—an example of the progressive agenda of many government propaganda programs during the Roosevelt era—and they too had voted to break up the agency.5 Stouffer’s Research Branch in the army did carry over into the postwar era, but under different leadership and with greatly reduced funding.6

Despite these shifts, the trend toward institutionalization and expansion of postwar psychological operations asserted itself at least as early as January 1946. That month, Truman established the Central Intelligence Group (CIG), the immediate predecessor to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), under the leadership of a political ally of the administration, General Hoyt Vandenberg of the Army Air Corps.7 The CIG’s charter limited the agency’s work to intelligence analysis; nonetheless, its offices provided an institutional umbrella for a number of OSS veterans with psychological warfare experience who might otherwise have returned to civilian life. Less than two years after that, Truman replaced the CIG with the CIA, the bulk of whose budget for the next decade was to be dedicated to covert warfare, “black” propaganda, and other psychological operations.8

A pronounced drift emerged throughout the U.S. intelligence community toward U.S. intervention abroad to reintegrate failing European empires, confront the Soviets, and link domestic dissent with communist movements overseas. In January 1946 Major General W. G. Wyman, chief of intelligence of the U.S. Army Ground Forces, prepared a lengthy analysis reflecting his view of the ideological threats facing the U.S. government and the measures he believed necessary to meet them. American soldiers, occupation forces in Germany, and civilians at home were all suffering from a serious “confusion of mind” when it came to Marxism, he said.

Where is the mental penicillin that can be applied to our loose thinking to insure the wholesome thought that is so urgently needed in our country today?… Our troubles of the day—labor, demobilization, the discontented soldier—these are the sores on which the vultures of Communism will feed and fatten.

Wyman then proposed his solution:

There must be some agency, some group either within or outside our national security forces, which can interest itself in these matters. There must be some weapon by which we can defend ourselves from the secret thing that is working at our vitals—this cancer of modern civilization.… A new government policy is desperately needed to implement [this] psychological effort.… We must combat this creeping shadow which is in our midst.9

Wyman’s proposals were never openly adopted in the United States, in part because cultural barriers in this country militate against a major military role in civilian politics. But the U.S. Army did undertake Wyman’s ideological campaigns within the armed forces and among civilian populations in areas then under U.S. military occupation such as western Germany, Japan, and parts of Austria. There the army’s former Psychological Warfare Division (now reincarnated as part of the Army’s Civil Affairs Division) began a massive campaign for strengthening ideological unity among U.S. forces and for remolding attitudes among the former enemy population.

Their effort must be ranked as one of the single largest campaigns of purposive communication ever undertaken by a democratic society. Brigadier General Robert McClure, the wartime chief of the Psychological Warfare Division, offered an inventory of the propaganda assets the army brought to bear on international audiences and on U.S. soldiers. McClure’s list began with RIAS radio in Berlin broadcasting into eastern Europe; the Stars and Stripes daily newspaper; more worldwide radio broadcasts than the Voice of America; troop education programs (a legacy of Stouffer’s work) in both Europe and the Far East; fifty to seventy-five new documentary films produced each year; up-to-the-minute newsreels in three languages produced each week; control of all U.S. commercial films shown in occupied regions; control of postal censorship and publication licensing of all newspaper, magazine, and book publishers in the U.S. zones; operation of cultural centers in sixty cities; publication of five glossy foreign-language magazines designed for distribution to foreign audiences (the U.S. State Department was producing but one such magazine, McClure noted with satisfaction); printing of literally hundreds of millions of educational pamphlets and leaflets; publication of daily U.S. military government newspapers in three countries; and much more.10 Not on McClure’s list, but noteworthy in the present context, were large public opinion survey operations under the leadership of polling specialists Frederick W. Williams and Leo Crespi (in Germany) and anthropologists Herbert Passin and John W. Bennett (in Japan). Both became important centers for development of U.S. overseas and foreign-language polling techniques.11

The United States often adopted propaganda and psychological operations as one substitute for U.S. soldiers abroad as America demobilized much of its wartime army after 1945. By the end of the decade of the 1940s, many U.S. policymakers regarded these efforts as having been largely successful, though not yet completed. Determining the effectiveness of these programs is probably impossible today, considering the passage of time and the difficulties inherent in any attempt to disentangle communication effects from other social factors. The point here, however, is that important factions in the U.S. security establishment believed propaganda and psychological warfare campaigns on this scale to be essential to U.S. national security, and they were willing to pour tens of millions of dollars into these programs. The perceived success of these campaigns reinforced arguments within the government in favor of expanded psychological operations against restless populations in Europe and the developing world, as well as against the Soviet Union and its satellites.

Similar developments were under way in the fields of “black” and “gray” propaganda, covert warfare, and other sensitive aspects of psychological warfare. Between 1946 and 1950, the Truman administration created a multimillion-dollar secret bureaucracy for conducting clandestine warfare. For nearly the next thirty years, the very existence of this bureaucracy was denied repeatedly.

Much of the story of U.S. covert operations in postwar Europe and Asia remains buried in classified files and is in fact protected by statute from disclosure through the Freedom of Information Act or routine declassification.12 The basic structure of this bureaucracy was revealed for the first time during the congressional investigations following the Watergate break-in, however. It is known, for example, that in the summer of 1946 Secretary of War Robert Patterson ordered the army to lay the administrative groundwork for the establishment of new Airborne Reconnaissance Units similar to the OSS teams that had assisted guerrilla struggles in Nazi-occupied France and Yugoslavia during the war.13 (Despite the name, these groups specialized in sabotage and paramilitary operations and had little to do with “reconnaissance” in its usual sense.) The following spring, the State-Army-Navy-Air Force Coordinating Committee (SANACC)—the highest level U.S. political-military coordinating body of the day—created an elite interagency subcommittee euphemistically titled the Special Studies and Evaluation Subcommittee to “take those steps that are necessary to keep alive the arts of psychological warfare … [and to ensure] that there should be a nucleus of personnel capable of handling these arts in case an emergency arises.”14

That summer, Congress passed the National Security Act, a sweeping reform of U.S. security agencies. This law created the CIA out of the earlier CIG, established the National Security Council (NSC) to advise the president on management of political-military strategy both at home and abroad, and reorganized the armed services.15 Among the first questions faced by the new CIA was that of the constitutionality of clandestine psychological operations. Within weeks of the founding of the agency, the CIA’s first director, Admiral Roscoe Hillenkoetter, asked the agency’s counsel for a formal legal opinion concerning whether the 1947 law had authorized “secret propaganda and paramilitary operations” in peacetime.

The CIA’s general counsel, Lawrence Houston, replied that it had not. The agency’s charter authorized intelligence gathering and analysis, Houston said, which meant the collection and review of facts. Covert warfare and secret propaganda operations had not been approved by Congress, and the CIA’s expenditure of taxpayer money on unauthorized activities would be against the law. Even if the president directly ordered covert operations, Houston continued, it would be necessary for Congress to specifically authorize the funds for them before they could be carried out legally.16

Houston’s concerns led to two National Security Council actions on December 9, 1947, that became the first formal foundation for U.S. covert warfare in peacetime. These decisions illustrate the extent to which U.S. psychological warfare has had, from its inception, multiple, overlapping layers of cover stories, deceits, and euphemistic explanations even within the secret councils of government. In this case the NSC created two such layers simultaneously, each contradicting the other.

First, the NSC approved a relatively innocuous policy document known as “NSC 4”, entitled “Coordination of Foreign Information Measures.” This assigned the assistant secretary of state for public affairs responsibility to lead “the immediate strengthening and coordination of all foreign information measures of the U.S. Government … to counteract effects of anti-U.S. propaganda.”17 Importantly, NSC 4 was classified as confidential, the lowest category of government secret. Tens of thousands of government employees are permitted access to confidential information, and the existence and nature of confidential policies can be publicly discussed with members of the press, although it is illegal to pass a confidential document to a person without a security clearance. As a practical matter, this meant that word of this confidential action would likely be publicized in the news media as an NSC “secret decision” within days, perhaps within hours.

That is precisely what took place. In time, a series of public decisions grew up around NSC 4 authorizing funding for the Voice of America, scholarly exchange programs, operation of “America House” cultural centers abroad, and similar overt propaganda programs. Officially, the policy of the U.S. government on such measures was that “truth is our weapon,” as Edward Barrett—who was soon to be put in charge of the effort—put it. Barrett’s widely promoted policy asserted that the United States openly presented its views on international controversies and frankly discussed the flaws and the advantages of U.S. society in a bid to win credibility for its point of view. This was not “propaganda” (in the negative sense of that word), Barrett insisted; it was “truth.”18

In reality, however, only minutes after completing action on NSC 4, the NSC took up a second measure: NSC 4-A. This was classified as “top secret,” a considerably stricter security rating. Legal circulation of top-secret papers is limited to authorized persons with a need to know of their contents; disclosure of even the existence of a top-secret decision to any person outside that circle is barred. In NSC 4-A, the NSC directed that the newly approved overt propaganda programs “must be supplemented by covert psychological operations.” The National Security Council’s resolution secretly authorized the CIA to conduct these officially nonexistent programs and to administer them through channels different from the “confidential” program (i.e., the public program) authorized under NSC 4.19

The NSC’s action removed the U.S. Congress and public from any debate over whether to undertake psychological warfare abroad. The NSC ordered that the operations themselves be designed to be “deniable,” meaning “planned and executed [so] that any U.S. Government responsibility for them is not evident to unauthorized persons and that if uncovered the U.S. Government can plausibly disclaim any responsibility.”20

This seemingly self-contradictory, multilayer approach helped construct a euphemistic, bureaucratic sublanguage of terms that permitted those who had been initiated into the arcana of national security to discuss psychological operations and clandestine warfare in varying degrees of specificity depending upon the audience, while simultaneously denying the very existence of these projects when it was politically convenient to do so—a phenomenon that is crucial to understanding the later role of U.S. social scientists in these enterprises. In an added twist, NSC 4 established an officially confidential (but in reality public) program concerning “Foreign Information Measures,” which were sometimes referred to as “psychological measures” or “psychological warfare” in public discussions. This paradoxical structure helped to preserve the myth that the United States was dealing with the world in a straightforward manner consistent with the ideals of democracy, while the Soviets were waging a different sort of cold war, one that relied on deceit, propaganda, and clandestine violence.21

Less than six months later, the National Security Council replaced NSC 4-A with a second, more sweeping policy decision known as NSC 10/2, which granted the CIA still greater authority for clandestine warfare. NSC 10/2 created an entirely new government branch under the CIA whose budget, personnel, and very existence was a state secret: the Office of Policy Coordination (OPC). In its first weeks of existence, the new group was named the Office for Special Projects, but this title was thought to be too revealing because the euphemism “special projects” had become associated with clandestine OSS activities during the war. The name was therefore changed to Office of Policy Coordination, although the organization was an operational group that had nothing to do with policy or its coordination.22 Frank Wisner, a brilliant, driven Wall Street lawyer who had played a prominent role in the OSS, became its chief.23

Administratively, the OPC was a division of the CIA, but it was funded through the State Department and answered to that department’s policy planning chief George F. Kennan on policy matters.24 In practice, that meant that the dynamic Wisner enjoyed considerable autonomy for his division. By 1952 Wisner’s “office” employed about six thousand personnel in forty-seven field stations in the United States and around the world. The OPC’s annual budget has never been officially made public and so remains disputed among historians, with estimates running from about $82 million annually in 1950 dollars to three times that amount.25 Virtually all of these funds were spent on “black” psychological warfare.

The NSC termed the OPC the United States’ “Psychological Warfare Organization.” Thus the phrase “psychological warfare”—with its connotation of media and persuasion, albeit of a hard-hitting sort—itself became a euphemism to conceal covert activities that most governments consider to be acts of war. As the OPC’s charter put it, the agency’s tasks included “propaganda, economic warfare; preventative direct action, including sabotage, anti-sabotage, demolition and evacuation measures; subversion against hostile states, including assistance to underground resistance movements, guerrillas and refugee liberations [sic] groups, and support of indigenous anti-communist elements in threatened countries of the free world.”26 OPC simultaneously created a specific branch for managing assassinations and kidnapping of “persons whose interests were inimical” to the United States, as well as for murdering double agents suspected of betraying U.S. intelligence agencies.27

William Corson, a career intelligence officer who investigated the origins of the OPC for a 1976 U.S. Senate inquiry, captured the same concepts in more informal—but perhaps more enlightening—terms:

The intelligence community’s reaction to the NSC’s apparently unanimous endorsement and support of the “dirty tricks” authorizations was swift. In their view no holds were barred. The NSC 10/2 decision was broadly interpreted to mean that not only the President but all the guys on the top had said to put on the brass knuckles and go to work. As word of NSC 10/2 trickled down to the working staffs in the intelligence community, it was translated to mean that a declaration of war had been issued with equal if not more force than if the Congress had so decided.28

In this context the phrase “psychological warfare” enjoyed multi-layered, often contradictory meanings, depending upon the degree to which the people using the phrase and their audience had been initiated into this officially nonexistent aspect of U.S. policy. For the public, the term seems to have implied basically overt, hard-hitting propaganda and other mass media activities. For the national security cognoscenti and for psychological warfare contractors, the same phrase extended to selected use of violence—but defining exactly how much violence was often sidestepped, even in top-secret records. Meanwhile, the U.S. government systematically denied responsibility for any specific act of violence, typically denouncing news reports of U.S.-sponsored clandestine operations as fabrications of communist propagandists.29 In this way, the Truman and Eisenhower administrations mobilized broad constituencies to support U.S. psychological warfare programs—including constituencies among social scientists and other academics—while at the same time evading accountability for what was actually taking place.