“Barrack and Trench Mates”

The threefold pattern of academic participation in psychological operations discussed earlier reached a new peak during the Korean War. Prior to 1950, much of the discussion of psychological warfare in academic journals had concerned World War II experiences or had focused on what should be done to implement a “psychological” strategy in the emerging cold war. From 1950 on, however, reports began to focus on ongoing psychological operations and on new, military-financed research into the effects of communication.

Many of the Korean War–era studies were presented by men who would come to be remembered as among the most prominent mass communication researchers of the day. In the end, it is they who wrote the textbooks, enjoyed substantial government and private contracts, served on the editorial boards of the key journals, and became the deans and emeritus professors of the most influential schools of journalism and mass communication in the United States. What can be seen here is the process of construction of social networks whose specialty became production of what was claimed to be “knowledge” about a particular topic—in this case, “knowledge” about communication.

Shortly after the opening of the Korean War in 1950, the air force sent Wilbur Schramm, John W. Riley, and Frederick Williams to Korea to interview anticommunist refugees and to study U.S. psychological operations. They prepared a classified study for the Air Force, a declassified, academic version for publication in POQ, and a mass market booklet titled The Reds Take a City.1 The popular Reds text provided war and atrocity stories tailored to support the United Nations police action in Korea. It was eventually translated into several Asian and European languages at U.S. government expense, and it became a mainstay of “authoritative” accounts of the Korean conflict.

Meanwhile, summaries and interim reports concerning BASR’s research in the Middle East for the Voice of America appeared in POQ on at least six occasions, one of which was a glowing review of Daniel Leraer’s book on the project, which was published in a POQ issue edited by Lerner himself.2 Methodological reports drawn from U.S. Air Force, Army, and Navy research projects proliferated in the academic literature in the wake of the Korean conflict,3 as did studies of Eastern European and Soviet communications behavior, at least one of which was almost certainly produced under contract with the CIA.4

The field of overt or “white” propaganda had evolved prior to Korea in somewhat the same way as had “black” propaganda and clandestine operations. Congress passed the Smith-Mundt Act authorizing a permanent U.S. Office of International Information (OII) less than three months after the National Security Council adopted NSC 4 and NSC 4-A in late 1947. This office evolved into the agency known today as the U.S. Information Agency (USIA) and its overseas arm, the U.S. Information Service (USIS). The Voice of America (VOA) was folded into this operation and its budget was sharply increased in the wake of the late 1940s crises in Czechoslovakia, Berlin, and China.5

At first, journalists and public relations executives seem to have enjoyed more influence than social scientists in U.S. overt propaganda operations. Doctrinal statements issued by the OII and the early USIA reflect the working theories of journalists and “commonsense” theories of lay observers (to use Denis McQuail’s media theory terminology,)6 rather than social science theories. They made only a vague distinction between elite and mass audiences for most U.S. propaganda, for example, although even the earliest academic exchange programs attempted to focus on foreign elites and young professionals likely to become members of elites. True, U.S. radio broadcasting to western Europe became fairly sophisticated, with audience research in the region contracted out to private survey specialists employing native interviewers. (The government used private cover for these surveys, it said, because acknowledgment of the U.S. sponsorship of the survey was seen as likely to influence respondents.) The costly and politically sensitive broadcasting to “closed” societies in eastern Europe and Communist China, on the other hand, was done on a wing and a prayer, with very little real knowledge of the extent to which U.S. radio signals were penetrating local jamming and no hard information at all as to how many people might be listening to the signals that did get through.7 U.S. intelligence and propaganda agencies knew very little of the effects of the U.S. program. Was it winning friends for the United States? Was harsher rhetoric effective—or should it be avoided? Did “information” programs really make any difference?

The government sought out social scientists who had cooperated during World War II to answer these questions in the wake of political attacks on the Voice of America and the U.S. information program by Senator Joseph McCarthy and his allies. The renewed relationship between the federal agencies and these scholars soon became symbiotic. Many social scientists regarded mass communication research as a promising, but seriously underfunded field, and they competed eagerly to land the new contracts. The government rewarded those who appeared to be most reliable and best able to make contributions to its ongoing propaganda, intelligence, and military training programs. As will be seen, one practical result of the competition for contracts was that much of the pressure for ideological conformity was not imposed from without but came from within the social science community.

“The Push-Button Millennium”

First, should communication studies undertaken for “white” propaganda outlets such as the Voice of America or the U.S. Information Agency properly be considered participation in U.S. psychological warfare? Study of Public Opinion Quarterly, the American Journal of Sociology, and other leading academic journals of the period shows clearly that many academic authors considered their work to be a form of psychological warfare and undertook their projects with that end in mind, particularly during the Korean War.

In the summer of 1951, for example, the annual meeting of the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) offered three major sessions focusing on psychological warfare that featured most of the prominent communication researchers of the era. In each session, the reported consensus of opinion was that U.S. international communication research could be best understood as a contribution to U.S. psychological operations. The Monday, June 25, session was chaired by W. Phillips Davison and titled “The Contributions of Public Opinion Research to Psychological Warfare.” Featured speakers included Elmo Wilson (of International Public Opinion Research), Leo Lowenthal (research director at the Voice of America), Daniel Lerner (Stanford University), and Joseph Stycos (BASR specialist in developing areas). Davison represented the RAND Corporation, which in those years was entirely dependent on U.S. Air Force and CIA contracts. The overall tone of the session was perhaps best captured by the anecdote Davison used when introducing Wilson, who had recently completed an ostensibly private, whirlwind public opinion study of five West European countries. The central question of Wilson’s surveys, “‘Who is on our [i.e., the U.S. government’s] side?’ was measured in terms of the willingness of people to do something about their feelings,” Davison said. But Wilson’s studies had been so demanding that the “Soviet agents tailing him had to be replaced for nervous exhaustion.”8

Lowenthal’s presentation summed up the Voice of America’s vision for communication studies with a bit of fancy: The Voice was seeking the “ultimate miracle,” namely, “the push-button millennium in the use of opinion research in psychological warfare. On that distant day,” Lowenthal continued, “the warrior would tell the research technician the elements of content, audience, medium and effect desired. The researcher would simply work out the mathematics and solve the algebraic formula” and the war would be won.9 In the later, published version of that paper (which Lowenthal coauthored with Joseph Klapper, who was then also at the VOA), Lowenthal termed the VOA’s international broadcasting “one type of psychological warfare” and said that communication studies and public opinion surveys were “barrack and trench mates in the present campaigns.”10

Joseph Stycos, who was at that time chief of the BASR project for the Voice of America in the Middle East, cited psychological warfare as the central rationale for the VOA project. He presented his survey of nomadic populations as primarily “important for the long-term study of psychological warfare”—not as scientifically valuable in its own right, or even as useful for facilitating “communication” in the sense of a two-way exchange of ideas between the nomads and the U.S. government.11

These sentiments were by no means confined to the Voice of America. A second AAPOR session, chaired by John MacMillan of the Office of Naval Research, focused on “Opinion and Communications Research in National Defense.” The U.S. Air Force’s presentation stressed several key areas of air force psychological interest, including “measurement of the ‘Panic Potential’ of a public, effectiveness of leaflet dropping as a means of communication, and the whole problem of psychological warfare.”12 Meanwhile, the AAPOR Presidential Session, chaired by Paul Lazarsfeld, featured as its keynote speaker Foy Kohler, chief of the International Broadcasting Division at the State Department. Kohler’s theme was “the role of public opinion in … the on-going world struggle for power between the United States and the Soviet Union.”13

A special POQ issue on International Communications Research published in winter 1952 marked a new high point in the integration of psychological warfare projects into academic communication studies. Guest-edited by Leo Lowenthal, who was at that time research director of the Voice of America, the special issue was the first formal compilation of state-of-the-art research and theory on international communication of the cold war. The project deserves special mention because it demonstrates the close interaction between “private” communication scholars and the government’s psychological warfare campaigns, as well as some aspects of a system of euphemistic language that served as a cover for that relationship.

Leo Lowenthal’s work on the POQ project and at the Voice of America exemplifies the complex, often contradictory pressures that whip-sawed intellectuals and scientists during the early cold war years. Lowenthal—a Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany, a self-described Marxist working for the U.S. government during a decidedly anticommunist era of U.S. history, and a culturally oriented critic of communication theory in the heyday of functionalism—was nothing if not a survivor and an iconoclast.14 Nevertheless, the trajectory of Lowenthal’s published ideas and of his career during the late 1940s and 1950s parallels—with one important exception to be discussed in a moment—those of a number of well known anticommunist liberals such as James Burnham, Jay Lovestone, Sidney Hook, and Max Eastman, all of whom spent years as Marxist theoreticians and activists prior to taking up cudgels against Stalin’s government. The widespread disillusionment with the “God that failed”15 as a hugely popular text of the period put it was driven along by a sense of betrayal generated by the Hitler-Stalin pact of 1939, the increasingly obvious brutality and antisemitism of Stalin’s regime, the stultifying intellectual life inside many communist political organizations, and, not least, a highly effective propaganda campaign in the West tailored to discredit and undermine support for revolution among intellectuals and labor leaders.16

By the late 1940s a number of the more important advisers to CIA and State Department psychological warfare campaigns had trained as Marxists at one point or another during their careers, and were now applying dialectics and other Marxian insights to the task of psychological warfare against the Soviet Union, China, and Third World nationalism. So too with Leo Lowenthal, whose principal critical writings and editorial work for Public Opinion Quarterly and other academic journals of the early 1950s are unambiguously dedicated to applying critical (Marxist or post-Marxist) insights to the task of improving U.S. international propaganda.17

Lowenthal’s modern recollections concerning his VOA years still reflect the ambivalence of many intellectuals of his day. “I’m not interested in posing as an ardent critic of American foreign policy,” Lowenthal commented years later during an interview concerning his government work.18

I looked at it from the vantage point of my specific function [at VOA]; after all, I was only the director of a certain department within the American propaganda apparatus that didn’t make political decisions itself … The governmental activity didn’t compromise either [Herbert] Marcuse [who had worked in German propaganda analysis for the OSS during World War II] or me.… I’d have to say that neither during the war, when I worked for the Office of War Information, nor in the postwar period [at VOA] did I ever have the feeling that I was working for an imperialist power.… After all, there were two superpowers opposing each other, and it’s difficult to make out just who—the United States or the Soviet Union—engaged in the more imperialistic politics right after the war.

As things turned out, Lowenthal was not like Burnham, Lovestone et al., in that he refused to become a professional anticommunist activist as the cold war deepened. He preferred instead to enter academe as a professor at Stanford and the University of California after being bounced out of his government job by the new Republican administration in 1952.19 In the end, Lowenthal may have succeeded during later years where many other academics have failed: He managed to adapt Marxist, functionalist, symbolic interactionism and other often mutually hostile intellectual traditions to one another, and he lived long enough to become something of a grand old man in the social sciences.20 But Lowenthal’s work in psychological warfare at the Voice of America was not an anomaly, in the final analysis; it was instead consistent in most respects with that of other reform-minded communication research scientists. Lowenthal’s experience at VOA points up the ambiguity and paradoxical character of the U.S. intelligentsia’s response to U.S. psychological warfare, and the extent to which otherwise iconoclastic scholars felt compelled to take sides in the superpower confrontations of the early cold war.

Lowenthal’s 1952 Public Opinion Quarterly text on international communication research provided a vehicle for articles that had in fact been prepared under government contract—though not publicly acknowledged as such—to be propagated within the sociological and social-psychological communities as advanced thinking on the subject of international communication. One example is Charles Glock’s “The Comparative Study of Communications and Opinion Formation,”21 a relatively detailed presentation on the concept of a national communication system, its relationship to mass audiences and opinion leaders in any given country, and an outline of methods for study of such systems. Lowenthal presented Glock’s work to POQ readers as simply a product of the Bureau of Applied Social Research, without further reference to the social and political context in which dock’s concept had emerged. However, the recently opened archives of the Bureau of Social Science Research indicate that dock’s work had in fact been underwritten by the Department of State as part of a joint BASR-BSSR project to improve techniques of manipulating public opinion in Italy and the Near East, both of which were major targets of U.S. psychological operations of the day.22

Political considerations clearly shaped dock’s research agenda. “We would like to know to what extent the nationalistic awakening among former colonial peoples in the East has led to a general distrust of anything which comes from the ‘imperialist’ West,” dock stressed. “In Egypt, there is some evidence that among intellectuals, news from America is viewed somewhat ambivalently.… What needs to be studied, then, in the area of opinion formation is the different ways in which information about the world is absorbed … under varying social, political and economic systems.”23

Whatever the scientific merit of dock’s analysis, it is evident that his project was applied political research designed to support a particular aim, namely, the advancement among the populations of Italy and the Near East of the U.S. government’s conceptions of its national interest. The adoption of Glock’s insights by other mass communication scientists of the period was also carried out within the same ideological framework. Glock’s work did not become, as some might have it, simply a neutral scientific advance that would be taken up by others without the political baggage that had been imposed by its original sponsors. Instead, as a practical matter, virtually all U.S. research into “national communication systems” during the decade that followed Glock was underwritten by the Department of State and the U.S. Army as a means of achieving the same political and ideological ends that had motivated the initial sponsorship of dock’s project. The BSSR archives make that point clearly: dock’s writings provided the foundation for a successful 1953 contract bid by the BSSR to develop further studies along the same line for Lowenthal’s office at the Department of State,24 for a series of studies concerning the “national communications systems” of the Eastern European satellite countries25 and of the Philippines26 and, later, for similar studies on behalf of the U.S. Army concerning communication systems in the Asian republics of the Soviet Union.27

Several other articles in the same special issue of POQ have similar characteristics. Benjamin Ringer and David Sills’ “Political Extremists in Iran: A Secondary Analysis of Communications Data” presented itself as simply a BASR study of opinion data concerning an unstable Middle Eastern country. In reality, it was a product of a State Department–sponsored study of political trends in a country that was at that moment in the midst of a CIA-sponsored coup d’état to remove the nationalist government of Mohammed Mossadegh, whose supporters made up many of the purported “political extremists” of the article’s title.28 Roughly similar attributes can be found in the special issue’s reporting on Soviet communications behavior29 and communist radio broadcasting to Italy30 and in a methodological discussion of the value of interviews with refugees from Eastern Europe as a barometer of the effectiveness of U.S. propaganda.31

Daniel Lerner provided ideological guidance for readers of the special issue. Lerner’s contention, which was presented at length and without reply from opposing views, was that scholars who failed to embrace U.S. foreign policy initiatives “represent a total loss to the Free World.” As Lerner saw it—and presumably as the editors saw it as well, for they endorsed Lerner’s stand—campaigns against purportedly “neutralist” sentiments such as “peace, safety [and] relaxation [of tensions]” were the “responsibility of everyone able and willing to improve the coverage, depth and relevance of communications research.”32

The “private” context created by publication in POQ also helped advance the system of euphemism that insulated scholars from the actual uses to which their work was put. Lowenthal’s work provides an example. In the summer of 1952, Lowenthal wrote frankly in Public Opinion Quarterly that “research in the field of psychological warfare” was a major aspect of the Voice of America work he was supervising.33 But less than six months later, the special issue he edited dedicated to “International Communications Research” contains no explicit articles on psychological warfare qua psychological warfare at all34—a fact that was illustrated in POQ’s index for 1952, which listed only two published articles on “propaganda” and none at all on “psychological warfare.”

This insulation proved effective. Four of the major articles from the Lowenthal issue, including Glock’s, were recycled for university audiences for the next twenty years in Wilbur Schramm’s college text The Process and Effects of Mass Communication, which is widely regarded as a founding text of graduate mass communication studies in the United States.35 This work challenged the popular preconception that media audiences behave as an undifferentiated mass, which is also sometimes known as the “magic bullet” approach to propaganda. Schramm went on to present theories and research results tailored to exploit what was then known of audience behavior—the “opinion leader” phenomenon, the tendency to create “reference groups,” and so on—as tactical elements in designing more successful campaigns to manipulate groups of people.

Schramm portrayed the reports as “communication research” rather than as, say, “psychological warfare studies.” Either description is accurate; the distinction between the two is that the former term tends to downplay the social context that gave birth to the work in the first place. Similarly, Schramm presented the source of these texts as being Public Opinion Quarterly, not government contracts, thus adding a gloss of academic recognition to the articles and further confounding an average reader’s ability to accurately interpret the context in which the original work was performed.36 Given this tacit deceit, the audience’s favored interpretation of the Schramm presentation is not likely to have been that Doctor Glock chose to make his living by offering advice on a particular type of communication behavior (international political propaganda), because that information had been stripped from the text that the audience saw. What the audience saw, rather, was an implicit claim, backed up by Public Opinion Quarterly credits, that the apparent consensus of scientific opinion is that international communication studies are largely an elaboration of methods for imposing one’s national will abroad.

The work of the Bureau of Social Science Research illustrates the interwoven relationship between federal programs and U.S. mass communication studies beginning during the Korean War and continuing throughout the 1950s. The BSSR was established at American University in 1950, and much of its archives are today held at American University and by the University of Maryland Libraries at College Park. During the 1950s BSSR employed prominent social scientists such as Robert Bower, Kurt Back, Albert Biderman, Elisabeth Crawford, Ray Fink, Louis Gottschalk, and Ivor Wayne.37

The BSSR contract data that have survived show that the U.S. Air Force funded BSSR studies on “targets and vulnerabilities in psychological warfare” of people in Eastern Europe and Soviet Kazakhstan; a project “directed toward understanding of various social, political and psychological aspects of violence … as it bears on control and exploitation of military power”; a report on “captivity behavior” and psychological collapse among prisoners of war; and a series of studies on the relative usefulness of drugs, electroshock, violence, and other coercive techniques during interrogation of prisoners.38 The Human Ecology Fund, which was later revealed to have been a conduit for CIA monies, underwrote BSSR’s studies of Africa and of prisoner interrogation methods.39 BSSR meanwhile enjoyed USIA contracts for training the South Vietnamese government in the collection of statistically sound data on its population, training USIA personnel in mass communication research techniques, collecting of intelligence on USIA audiences abroad, and performing a variety of data analysis functions.40 These contracts certainly contributed 50 percent, and perhaps as much as 85 percent, of BSSR’s budget during the 1950s.41

Beginning at least as early as 1951, the USIA hired BSSR (along with BASR and others) for a high-priority program to inculcate a state-of-the-art understanding of communication dynamics into the USIA’s overseas propaganda programs. The surviving archival record shows that the BSSR succeeded on at least three counts: it introduced modern audience survey methods,42 introduced the concept of “opinion leaders” and the distinction between “elite” and “mass” audiences for propaganda and psychological operations,43 and introduced the concept of a “national communication system” (as that phrase was used by Paul Lazarsfeld and Charles Glock)44 as a target for penetration by U.S. government propaganda.45

The BSSR studies for the State Department establish that, contrary to common wisdom, the widely recognized “personal influence” or “two-step” model of communication dynamics had become the backbone of USIA mass communication research at least four years before the publication of Elihu Katz and Paul Lazarsfeld’s watershed text on the topic, Personal Influence (1955).46 As early as 1951, Stanley Bigman of Lazarsfeld’s Bureau of Applied Social Research prepared a confidential manual on survey research entitled Are We Hitting the Target? for the U.S. International Information and Educational Exchange Program (USIE), the immediate predecessor of the USIA.47 (The BASR was at that time testing some aspects of “personal influence” models of communication behavior in a major project in the Middle East sponsored by the Voice of America).48 Shortly after completing the manual, Bigman transferred to BSSR, where he continued the Target project and undertook a follow-on contract in 1953 for study of public opinion and communication behavior in the Philippines.49 The Target manual stressed a number of concepts that were at the cutting edge of communication studies of the day, describing methods for using surveys to track the impact of “personal influence” networks on popular attitudes, tips on identifying local “opinion leaders” suitable for special cultivation, relatively sophisticated questionnaire design techniques, methods of compensating for interviewer bias, and similar state-of-the-art techniques that were well ahead of most academic opinion studies of the day.49 Bigman’s project taught the USIA how to use native Filipino interviewers to identify local opinion leaders; obtain detailed data on respondents’ sources of information on the United States; compile statistics on local attitudes toward democracy, nationalism, communism, and U.S.–Philippines relations; and secure feedback on the effectiveness of particular USIA propaganda efforts in the Philippines.

Bigman’s modest 1951 manual illustrates that the evolution of the “personal influence” concept was more complex and considerably more dependent upon government sponsorship than is generally recognized today. The most common version of this concept’s evolution traces it exclusively to New York State voting studies between 1945 and 1948 by Lazarsfeld, Berelson, and McPhee, then abruptly jumps forward to the publication of the New York data in Voting (1954)50 and more fully in Personal Influence (1955).51 In reality, however, BSSR and BASR work in propaganda and covert warfare in the Philippines and the Middle East accounts for most of the six years of development between the germination of the personal influence concept and its publication in book form.

The BSSR’s Philippines project of the early 1950s also demonstrated the ease with which ostensibly pluralistic, democratic conceptions of communication behavior and communication studies could be put to use in U.S.-sponsored counterinsurgency campaigns and in the management of authoritarian client regimes. Paul Linebarger, a leading U.S. psychological warfare expert specializing in Southeast Asia, bragged that the CIA had “invented” the Philippines’ president Raymon Magsaysay and installed him in office.52 Once there, “the CIA wrote [Magsaysay’s] speeches, carefully guided his foreign policy and used its press assets (paid editors and journalists) to provide him with a constant claque of support,” according to historian and CIA critic William Blum.53

The CIA’s idea at the time was to transform the Philippines into a “showplace of democracy” in Asia, recalled CIA operative Joseph B. Smith, who was active in the campaign.54 In reality, though, Magsaysay’s U.S.-financed counterinsurgency war against the Huk guerrillas became a bloody proving ground for a series of psychological warfare techniques developed by the CIA’s Edward Lansdale, not least of which was the exploitation of the USIA’s intelligence on Filipino culture and native superstitions. Tactics (and rhetoric) such as “search-and-destroy” and “pacification” that were later to become familiar during the failed U.S. invasion of Vietnam were first elaborated under Lansdale’s tutelage in the Philippines.55

The relationship between the USIA and the CIA in the Philippines can be best understood as a division of labor. The two groups are separate agencies, and the USIA insists that it does not provide cover to the CIA’s officers abroad.56 But intelligence gathered by the USIA, such as that obtained through Bigman’s surveys of Filipino “opinion leaders,” is regularly provided to the CIA, according to a report by the House Committee on Foreign Affairs.57 USIA and CIA work was first coordinated through “country plans” monitored by area specialists at President Truman’s secretive Psychological Strategy Board (established in 1951) and, later, at the National Security Council under President Eisenhower.58 By the time the Philippines project was in high gear during the mid-1950s, Eisenhower had placed policy oversight of combined CIA-USIA-U.S. military country plans in the hands of senior aides with direct presidential access—C. D. Jackson and later Nelson Rockefeller—who personally monitored developments and formulated strategy.59

At the time, the implicit claim of BSSR’s work for the government was that application of “scientific” psychological warfare and counterinsurgency techniques in the Philippines would lead to more democracy and less violence overall than had, say, the crude massacres of 1898–1902, when a U.S. expeditionary force suppressed an earlier rebellion by Philippine nationalist leader Emilio Aguinaldo.

But looking back today, there is little evidence that such claims ever were true. More than forty years has passed since BSSR and the USIA’s work in the Philippines began. The Huks were defeated; a relatively stable, pro-Western government was established in the country; and a handful of Filipinos have prospered. Yet by almost every indicator—infant mortality, life expectancy, nutrition, land ownership, education, venereal disease rates, even the right to publish or to vote—life for the substantial majority of Filipinos has remained static or gotten worse over those four decades.

BSSR’s academics did not set U.S. policy in the Philippines, of course. But they did provide U.S. military and intelligence agencies with detailed knowledge of the social structure, psychology, and mood of the Philippines population, upon which modern antiguerrilla tactics depend. Despite its claims, U.S. psychological warfare campaigns in the Philippines and throughout the developing world have generally increased the prevailing levels of violence and misery, not reduced them.

Military Sponsorship of “Diffusion” Research

While the USIA and Voice of America’s psychological warfare projects were usually more or less overt and the CIA’s covert, those of the U.S. armed services generally fell somewhere between the extremes. The military agencies underwrote several of the best known and most influential communication research projects performed during the 1950s, though their contribution was not always publicly acknowledged at the time.

A telling example of this can be found in Project Revere, a series of costly, U.S. Air Force–financed message diffusion studies conducted by Stuart Dodd, Melvin DeFleur, and other sociologists at the University of Washington. Lowery and DeFleur’s later textbook history of communication studies calls Revere one of several major “milestones” in the emerging field.60 Briefly, Project Revere scientists dropped millions of leaflets containing civil defense propaganda or commercial advertising from U.S. Air Force planes over selected cities and towns in Washington state, Idaho, Montana, Utah, and Alabama. They then surveyed the target populations to create a relatively detailed record of the diffusion of the sample message among residents. The air force sponsorship of the program was regarded as classified at the time and was not acknowledged in Dodd’s early report on the project in Public Opinion Quarterly.61 Later accounts by Dodd, DeFleur, and others were more frank, however.62 The air force invested about a “third of a million 1950s dollars” in the effort, Lowery and DeFleur later pointed out,63 making it one of the largest single investments in communication studies from the end of World War II through the mid-1950s.

Project Revere embodied the complex dilemmas and compromises inherent in the psychological warfare studies of the era. For Dodd and his colleagues, the money represented “an almost unprecedented opportunity” for “research into basic problems of communications.”64 The catch, however, was that the studies had to focus on air-dropped leaflets as a means of communication. This medium was an important part of U.S. Air Force propaganda efforts in the Korean conflict, in CIA propaganda in Eastern Europe, and in U.S. nuclear war–fighting strategy during the 1950s, but it had no substantial “civilian” application whatever.65

Dodd and his team contended that the leaflets could be employed as an experimental stimulus to study properties of communication that were believed to be common to many media, not leaflets alone. They developed elaborate mathematical models describing the impact of a new stimulus, its spread, then the leveling off of knowledge of the stimulus. They stressed the data that were of most interest to the contracting agency: the optimum leaflet-to-population ratio, effects of repeated leaflet drops on audience recall of a message, effect of variations in timing of drops, and so on. Perhaps the most important lesson of general applicability derived from the project, according to De Fleur, was that diffusion of any given message from person to person—which is to say, through the second step of “two-step” social networks—necessarily involves great distortion of even very simple messages.66

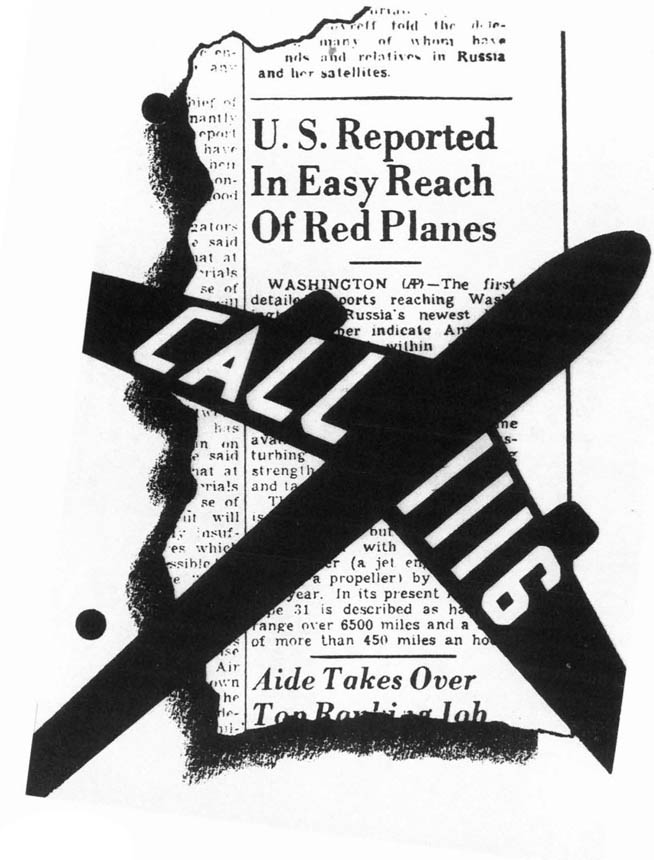

Figure 2

Figure 3

The project generated dozens of articles for scholarly journals, books, and theses. De Fleur, Otto Larsen, Ørjar Øyen, John G. Shaw, Richard Hill, and William Catton based dissertations on Revere data.67 In 1958, Public Opinion Quarterly published a chart Dodd had prepared of what he termed “Revere-connected papers” (see Appendix). A glance at the titles and journals on Dodd’s list vividly illustrates the manner in which work performed under classified government contracts entered the mainstream of the mass communication studies and the extent of penetration that it achieved.

Dodd’s project was both a study of propaganda and a propaganda project in its own right. The sample messages clearly served to stimulate popular fear of atomic attacks by Soviet bombers at the height of the famous (and contrived) “bomber gap” war scare of the 1950s (see Figure 2). In reality, many of the communities targeted in Dodd’s study were at that time inaccessible to American commercial airliners, much less Soviet bombers. Most historians today agree that the U.S. Air Force manufactured the purported bomber gap to shore up its position in internal Eisenhower administration debates over strategic nuclear policy.68

No opposition among Dodd’s team of academics to the actual or potential applications of their studies has come to light thus far. It is worth noting, however, that the CIA abruptly canceled its European air-dropped leaflet program in 1956 following a fatal crash by a Czech civilian airliner whose controls became entangled in a flight of the balloons used to carry the leaflets into Czech airspace. The U.S. government publicly disclaimed any responsibility for the crash or for the officially nonexistent leaflet propaganda program.69

The CIA and the Founding Fathers of Communication Studies

Turning to a consideration of CIA-sponsored psychological warfare studies, one finds a wealth of evidence showing that projects secretly funded by the CIA played a prominent role in U.S. mass communication studies during the middle and late 1950s. The secrecy that surrounds any CIA operation makes complete documentation impossible, but the fragmentary information that is now available permits identification of several important examples.

The first is the work of Albert Hadley Cantril (better known as Hadley Cantril), a noted “founding father” of modern mass communication studies. Cantril was associate director of the famous Princeton Radio Project from 1937 to 1939, a founder and longtime director of Princeton’s Office of Public Opinion Research, and a founder of the Princeton Listening Center, which eventually evolved into the CIA-financed Foreign Broadcast Information Service. Cantril’s work at Princeton is widely recognized as “the first time that academic social science took survey research seriously, and it was the first attempt to collect and collate systematically survey findings.”70 Cantril’s The Psychology of Radio, written with Gordon Allport, is often cited as a seminal study in mass communication theory and research, and his surveys of public opinion in European and Third World countries defined the subfield of international public opinion studies for more than two decades.

Cantril’s work during the first decade after World War II focused on elaborating Lippmann’s concept of the stereotype—the “pictures in our heads,” as Lippmann put it, through which people are said to deal with the world outside their immediate experience. Cantril specialized in international surveys intended to determine how factors such as class, nationalism, and ethnicity affected the stereotypes present in a given population, and how those stereotypes in turn affected national behavior in various countries, particularly toward the United States.71 Cantril’s work, while often revealing the “human face” of disaffected groups, began with the premise that the United States’ goals and actions abroad were fundamentally good for the world at large. If U.S. acts were not viewed in that light by foreign audiences, the problem was that they had misunderstood our good intentions, not that Western behavior might be fundamentally flawed.

Cantril’s career had been closely bound up with U.S. intelligence and clandestine psychological operations since at least the late 1930s. The Office of Public Opinion Research, for example, enjoyed confidential contracts from the Roosevelt administration for research into U.S. public opinion on the eve of World War II. Cantril went on to serve as the senior public opinion specialist of the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs (an early U.S. intelligence agency led by Nelson Rockefeller and focusing on Latin America), of the World War II Office of War Information, and, in a later period, as an adviser to President Eisenhower on the psychological aspects of foreign policy. During the Kennedy administration, Cantril helped reorganize the U.S. Information Agency.72

According to the New York Times, the CIA provided Cantril and his colleague Lloyd Free with $1 million in 1956 to gather intelligence on popular attitudes in countries of interest to the agency.73 The Rockefeller Foundation appears to have laundered the money for Cantril, because Cantril repeatedly claimed in print that the monies had come from that source.74 However, the Times and Cantril’s longtime partner, Lloyd Free, confirmed after Cantril’s death that the true source of the funds had been the CIA.75

Cantril’s first target was a study of the political potential of “protest” voters in France and Italy, who were regarded as hostile to U.S. foreign policy.76 That was followed by a 1958 tour of the Soviet Union under private, academic cover, to gather information on the social psychology of the Soviet population and on “mass” relationships with the Soviet elite. Cantril’s report on this topic went directly to then president Eisenhower; its thrust was that treating the Soviets firmly, but with greater respect—rather than openly ridiculing them, as had been Secretary of State John Foster Dulles’ practice—could help improve East–West relations.77 Later Cantril missions included studies of Castro’s supporters in Cuba and reports on the social psychology of a series of countries that could serve as a checklist of CIA interventions of the period: Brazil, the Dominican Republic, Egypt, India, Nigeria, Philippines, Poland, and others.78

An important focus of Cantril’s work under the CIA’s contract were surveys of U.S. domestic public opinion on foreign policy and domestic political issues—a use of government funds many observers would argue was illegal.79 There, Cantril introduced an important methodological innovation by breaking out political opinions by respondents’ demographic characteristics and their place on a U.S. ideological spectrum he had devised—a forerunner of the political opinion analysis techniques that would revolutionize U.S. election campaigns during the 1980s.80

A second—and perhaps more important—example of the CIA’s role in U.S. mass communication studies during the 1950s was the work of the Center for International Studies (CENIS) at MIT. The CIA became the principal funder of this institution throughout the 1950s, although neither the CENIS nor the CIA is known to have publicly provided details on their relationship. It has been widely reported, however, that the CIA financed the initial establishment of the CENIS; that the agency underwrote publication of certain CENIS studies in both classified and nonclassified editions; that CENIS served as a conduit for CIA funds for researchers at other institutions, particularly the Center for Russian Research at Harvard; that the director of CENIS, Max Millikan, had served as assistant director of the CIA immediately prior to his assumption of the CENIS post; and that Millikan served as a “consultant to the Central Intelligence Agency,” as State Department records put it, during his tenure as director of CENIS.81 In 1966, CENIS scholar Ithiel de Sola Pool acknowledged that CENIS “has in the past had contracts with the CIA,” though he insisted the CIA severed its links with CENIS following a bitter scandal in the early 1960s.82

CENIS emerged as one of the most important centers of communication studies midway through the 1950s, and it maintained that role for the remainder of the decade. According to CENIS’s official account, the funding for its communications research was provided by a four-year, $850,000 grant from the Ford Foundation, which was distributed under the guidance of an appointed planning committee made up of Hans Speier (chair), Jerome Bruner, Wallace Carroll, Harold Lasswell, Paul Lazarsfeld, Edward Shils, and Ithiel de Sola Pool (secretary).83 It is not known whether Ford’s funds were in fact CIA monies. The Ford Foundation’s archives make clear, however, that the foundation was at that time underwriting the costs of the CIA’s principal propaganda project aimed at intellectuals, the Congress for Cultural Freedom, with a grant of $500,000 made at CIA request, and that the Ford Foundation’s director, John McCloy (who will be remembered here for his World War II psychological warfare work), had established a regular liaison with the CIA for the specific purpose of managing Ford Foundation cover for CIA projects.84 Of the men on CENIS’s communication studies planning committee, Edward Shils was simultaneously a leading spokesman for the CIA-backed Congress for Cultural Freedom project; Hans Speier was the RAND Corporation’s director of social science research; and Wallace Carroll was a journalist specializing in national security issues who had produced a series of classified reports on clandestine warfare against the Soviet Union for U.S. military intelligence agencies.85 In short, CENIS communication studies were from their inception closely bound up with both overt and covert aspects of U.S. national security strategy of the day.

The CENIS program generated the large majority of articles on psychological warfare published by leading academic journals during the second half of the 1950s. CENIS’s dominance in psychological warfare studies during this period was perhaps best illustrated by two special issues of POQ published in the spring of 1956 and the fall of 1958. Each was edited by CENIS scholars—by Ithiel de Sola Pool and Frank Bonilla and by Daniel Lerner, respectively—and each was responsible for the preponderance of POQ articles concerning psychological warfare published that year. The collective titles for the special issues were “Studies in Political Communications” and “Attitude Research in Modernizing Areas.”86

CENIS scholars and members of the CENIS planning committee such as Harold Isaacs, Y. B. Damle, Claire Zimmerman, Raymond Bauer, and Suzanne Keller87 and each of the special issue editors88 provided most of the content. They drew other articles from studies that CENIS had contracted out to outside academics, such as a content analysis of U.S. and Soviet propaganda publications by Ivor Wayne of BSSR and a study of nationalism among the Egyptian elite by Patricia Kendall of BASR that was based on data gathered during the earlier Voice of America studies in the Mideast.89

The purported dangers to the United States of “modernization” or economic development in the Third World emerged as the most important theme of CENIS studies in international communication as the decade of the 1950s drew to a close. Practically without exception, CENIS studies coincided with those issues and geographic areas regarded as problems by U.S. intelligence agencies: “agitators” in Indonesia, student radicals in Chile, “change-prone” individuals in Puerto Rico, and the social impact of economic development in the Middle East.90 CENIS also studied desegregation of schools in Little Rock, Arkansas, as an example of “modernization.”91

In these reports, CENIS authors viewed social change in developing countries principally as a management problem for the United States. Daniel Lerner contended that “urbanization, industrialization, secularization [and] communications” were elements of a typology of modernization that could be measured and shaped in order to secure a desirable outcome from the point of view of the U.S. government. “How can these modernizing societies-in-a-hurry maintain stability?” Lerner asked. “Whence will come the compulsions toward responsible formation and expression of opinion on which a free participant society depends?”92

In The Passing of Traditional Society and other texts, Lerner contended that public “‘participation’ [in power] through opinion is spreading before genuine political and economic participation” in societies in developing countries93—a clear echo of Lippmann’s earlier thesis. This created a substantial mass of people who were relatively informed through the mass media, yet who were socially and economically disenfranchised, and thus easily swayed by the appeals of radical nationalists, Communists, and other “extremists.” As in Lippmann’s analysis, mass communication played an important role in the creation of this explosive situation, as Lerner saw it, and in elite management of it. He proposed a strategy modeled in large part on the campaign in the Philippines that combined “white” and “black” propaganda, economic development aid, and U.S.-trained and financed counterinsurgency operations to manage these problems in a manner that was “responsible” from the point of view of the industrialized world.

This “development theory,” which combined propaganda, counter-insurgency warfare, and selective economic development of targeted regions, was rapidly integrated into U.S. psychological warfare practice worldwide as the decade drew to a close. Classified U.S. programs employing “Green Beret” Special Forces troops trained in what was termed “nation building” and counterinsurgency began in the mountainous areas of Cambodia and Laos.94 Similar projects intended to win the hearts and minds of Vietnam’s peasant population through propaganda, creation of “strategic hamlets,” and similar forms of controlled social development under the umbrella of U.S. Special Forces troops can also be traced in part to Lerner’s work, which was in time elaborated by Wilbur Schramm, Lucian Pye, Ithiel de Sola Pool, and others.95 Lerner himself became a fixture at Pentagon-sponsored conferences on U.S. psychological warfare in the Third World during the 1960s and 1970s, lecturing widely on the usefulness of social science data for the design of what has since come to be called U.S.-sponsored low-intensity warfare abroad.96

The Special Operations Research Office’s 1962 volume The U.S. Army’s Limited-War Mission and Social Science Research and the well-publicized controversy surrounding Project Camelot97 show that the brutal U.S. counterinsurgency wars of the period grew out of earlier psychological warfare projects, and that their tactics were shaped in important part by the rising school of development theory.98 Further, the promises integral to that theory—namely, that U.S. efforts to control development in the Third World, if skillfully handled, could benefit the targets of that intervention while simultaneously advancing U.S. interests—were often publicized by the USIA, by the Army’s mass media, at various academic conferences, and in other propaganda outlets. In other words, as the government tested in the field the tactics advocated by Lerner, Pool, and others, the rationalizations offered by these same scholars became propaganda themes the government promoted to counter opposition to U.S. intervention abroad.99

The important point with regard to CENIS is the continuing, inbred relationship among a handful of leading mass communication scholars and the U.S. military and intelligence community. Substantially the same group of theoreticians who articulated the early cold war version of psychological warfare in the 1950s reappeared in the 1960s to articulate the Vietnam era adaptation of the same concepts. More than a half-dozen noted academics followed this track: Daniel Lerner, Harold Lasswell, Wilbur Schramm, John W. Riley, W. Phillips Davison, Leonard Cottrell, and Ithiel de Sola Pool, among others.100

This continuity of leading theoreticians became part of a broader pattern through which the “psychological warfare” of one generation became the “international communication” of the next. By about the mid-1950s, mass communication research was beginning to achieve some measure of scientific “professionalism” as a distinct discipline. Jesse Delia’s history of the field captures one aspect of the shift well. Mainstream mass communication scholars’

shared … commitment to pursue scientific understanding of mass communication’s practical and policy aspects was transformed by the achieved professionalism of social scientists into pursuits defined within the questions and canons of established social science disciplines. Within many of the disciplines, the accepted canons of professionalism defined theoretical questions as of principal significance and sustained the bracketing of overtly value-centered questions.… By the end of the 1950s this attitude was firmly fixed as a core commitment among the majority of communications researchers.101

In other words, Delia argues, mass communications research became more “scientific,” placed greater stress on theory, and took an increasingly objective view of the “values” (or social impact) of any given piece of applied research.

But Delia’s insight should be stood on its head, so to speak, in order to more accurately reflect reality. Prominent mass communication researchers such as Lasswell, Lerner, Schramm, Pool, and Davison never abandoned the “practical and policy aspects of mass communications” (which is to say, psychological warfare and similar applied research projects for government and commercial customers), as Delia would seem to have it. Instead, they absorbed the values and many of the political attitudes of the psychological warfare projects into new, “scientificized” presentations of theory that tended to conceal the ethical and political presumptions of the early 1950s programs under a new coat of “objective” rhetoric.

The professionalization and institutionalization of the discipline brought with it a series of interesting rhetorical shifts that downplayed the relatively blatant convergence of interests between mainstream mass communication research and its funders that had characterized the first decade after 1945. A new rhetoric, one which was self-consciously “neutral” and “scientific,” began to emerge. But the core conceptions about what communications “is” and what to do with it remained intact. This process of changing the labels while maintaining the core concept of employing communication principally as an instrument of domination can be clearly seen in some of those projects unfortunate enough to be caught on the cusp of the change.

At the Bureau of Social Science Research, for example, Chitra M. Smith prepared an extensive, annotated series of bibliographies for the RAND Corporation during 1951–54 entitled International Propaganda and Psychological Warfare.102 This was clearly an “old”-style rhetorical presentation. It is useful from a historical point of view, however, because as an annotated bibliography, Chitra Smith’s work provides a good indication of the scope of the concept of “psychological warfare” as it stood during the first half of the 1950s.

But by 1956 the rhetorical tide seems to have turned. That year, RAND compiled and published Smith’s bibliographies with only two substantive changes: The title became International Communication and Political Opinion, and the author’s credit was extended to both Bruce Lannes Smith and Chitra M. Smith.103 The earlier acknowledgment of psychological warfare as the unifying theme of the collection—in fact, as its raison d’être—completely disappeared, without changing the content of the work.

A similar incident took place at Harvard’s Russian Research Center. In 1954, Clyde Kluckhohn, Alex Inkeles, and Raymond Bauer prepared a psychological warfare study for the U.S. Air Force entitled “Strategic Psychological and Sociological Strengths and Vulnerabilities of the Soviet Social System.”104 Much of the work concerned the Soviet national communication system, which was Inkeles’ specialty, including its technological, cultural, and political attributes. In 1956, the authors deleted about a dozen pages of recommendations concerning psychological operations during nuclear war then published the identical four-hundred-page text under the new title How the Soviet System Works.105 That work, in turn, became a standard graduate reader in Soviet studies throughout the 1960s. The Kluckhohn, Inkeles, and Bauer text thus moved from its original incarnation as a relatively “naive” how-to manual for the exploitation of a rival communication system, to now make a much more sweeping—yet paradoxically more seemingly “objective” and “scientific”—claim concerning how Soviet reality “works.”

These examples illustrate both the changes and the underlying continuity of mainstream mass communication research in the United States during the 1950s. Leonard Doob—author of the 1948 text Public Opinion and Propaganda and an activist in U.S. international propaganda projects until well into the 1980s—expressed the rhetorical shift well in an interview with J. M. Sproule:

Doob indicates that the very term “propaganda” began to lose favor as the more objective [purportedly objective—author’s note] concepts of communication, persuasion and public opinion replaced it in the lexicon of social science. Indeed, Doob reports he would not have dreamed of using propaganda as a significant theoretical term in his 1961 study of Communication in Africa.106

In truth, Doob’s 1961 study was no less about “propaganda” in content or in the use to which it was put than had been his earlier work. What had changed was the rhetorical framework in which the concept of communication-as-domination was presented to the reader.

By the middle of the 1950s the process of stripping the social context from research and development in psychological warfare and recycling the remaining core concepts as simple “communication” research was well advanced. By then, several of the early claims made for the power that would flow from discovery of the “magic keys” to communication behavior had failed to prove out. Many mass communication experts had begun to regard the term “psychological warfare” as counterproductive, due to the hostility it generated among audiences targeted for persuasion. Discussing psychological warfare “in the public prints,” as Leo Bogart wrote in a report to the U.S. Information Agency, “is like describing the technique of seduction, and how to make it look like wooing, in the presence of the girl you have seduced.”107 Further, as L. John Martin argued, openly acknowledging campaigns of psychological warfare during peacetime opens the sponsor to charges of violation of United Nations conventions and international law.108

As early as the American Association for Public Opinion Research convention of 1954, researchers under contract to the Voice of America and to an unidentified government agency publicly reported the failure of two forms of mass communication research that had been particularly popular with government clients.109 Content analysis of foreign propaganda had been sold to the U.S. government on the basis of claims that careful monitoring of suspect publications could help predict shifts in the policies of rival regimes, and that it would reveal clandestine collaboration between Soviet propaganda agencies and ostensibly non-communist publications around the world. Both claims had been based in large part on studies by Harold Lasswell, Nathan Leites, Ithiel de Sola Pool, and others in the World War II–era Library of Congress psychological warfare team. But researchers at the Bureau of Social Science Research, Harvard, and Rutgers reported in 1954 that they had failed to achieve the desired results.110 Similarly, the VOA’s Helen Kaufman indicated that VOA studies in Germany focusing on means for defusing Soviet claims of racial injustice in the United States had failed to support Hovland’s widely accepted theories concerning audience responses to “one-sided” and “two-sided” propaganda.111 Elsewhere that year, W. Phillips Davison wrote that “in general” he felt that “the role of agitation and propaganda in the communist equation has been exaggerated.”112 The myth of the “push-button millennium” in government propaganda had begun to unravel.

At the AAPOR conference of 1956, an analyst with the CIA’s Radio Free Europe decisively broke ranks. Gerald Streibel opened his presentation with a conventional acknowledgment that scholarly psychological warfare research was desirable, but he continued by saying that despite heavy government funding of applied mass communication research the “gap between the [psychological warfare] operator and the researcher is almost as wide as ever.” Operators needed day-to-day information for “policy-making,” he contended, and academics had failed to provide it. In the real world “psychological warfare is not so much anti-scientific as it is pre-scientific,” he said. The magic keys sought by the state had simply not materialized, leading Radio Free Europe to turn to “journalists and other specialists” for their information and insights into propaganda techniques. “Psychological warfare is concerned with persuading people, not with studying them,” he concluded.113

Streibel’s comments created a minor crisis in the workshop. The session’s reporter—the BASR’s David Sills, who will be remembered from the Iranian “extremists” study mentioned earlier in this chapter—inserted a special note in the record stating that the Radio Free Europe paper “runs counter to many basic assumptions of applied research” and “represents a misunderstanding of both … policy-making and the potentialities of applied research.” Each of the other speakers at the gathering attacked Streibel’s conclusions.114

But the writing was on the wall. The problem with psychological warfare was but one aspect of a broader crisis in academic efforts to find Lowenthal’s “push-button millennium.” In the year that followed, prominent communication author William Albig reviewed the previous twenty years of communication studies and concluded that while output of papers in the field remained high, he was “not encouraged” by their depth. Little had been learned of “meaningful, theoretical significance about communications … [or] about the theory of public opinion.” There had been a plethora of descriptive and empirical studies, but little useful synthesis about opinion formation and change, he contended.115 Bernard Berelson was similarly pessimistic. The University of Chicago scholar concluded that the “‘great ideas’ that gave the field of communications research so much vitality ten and twenty years ago have to a substantial extent worn out. No new ideas of comparable magnitude have appeared to take their place. We are on a plateau.”116 Even two of psychological warfare’s most determined boosters, John Riley of Rutgers University and Leonard Cottrell of the Russell Sage Foundation, acknowledged at about that time that “disillusionment” had set in regarding the prospects for breakthroughs in the effectiveness of psychological warfare on the basis of existing concepts of applied communication research.117

Despite these discouraging words, what was in fact taking place was not the end of psychological warfare, but a shift in its targets and in some aspects of its rhetoric. The conceptualization of international conflict associated with MIT’s Center for International Studies was coming to the fore. The early popularity of the “propaganda” aspects of psychological war—which is to say, those most directly tied to communication media—was in decline among government funders, while CENIS’s vision of a broader, integrated strategy for “developing” entire nations was on the rise. The CENIS approach, it will be recalled, held that technological innovations in mass communication had helped create an explosive situation in developing countries by implicitly encouraging political participation by millions of people who remained economically and socially disenfranchised. The mass media were an important tool for managing that crisis CENIS argued; they could help educate people in new skills and make other positive contributions. But media alone were not enough. The United States should also organize suitable economic, political, and military institutions as part of the package. For those countries where the media and an aid package were not enough to stabilize the situation, CENIS said, the United States should provide arms, police, military advisers, and counterinsurgency support. Thus the CENIS approach came to be called “development theory” by communication specialists; among military planners it took the name “limited warfare.”118

CENIS’s work also became important in communication theory, narrowly defined. By the end of 1956, there was general agreement among CENIS specialists that audience effects played a substantial role in the communication process—the study of these effects, after all, was the basic rationale for the CENIS communication research program. Study of the “reception, comprehension and recall of political communications in underdeveloped or peasant societies” moved to center stage.119 There was also tacit agreement that elite populations abroad should be the first targets of persuasive communication.

The “old style” of psychological warfare, and particularly its emphasis on Soviet and East European targets, seems to have come to be regarded as a slightly stagnant, albeit still important field. In the 1956 special CENIS issue of Public Opinion Quarterly, for example, editor Ithiel de Sola Pool limited articles concerning the Soviets to six out of forty-one published in the issue—a quite different balance from that found in the 1952 special issue on International Communications Research edited by Leo Lowenthal. Even Pool’s introduction to the journal’s section dealing with Soviet and Chinese Communist political communication has the feel of a backhanded compliment: The articles in the section, he wrote, show a sophistication of analysis that comes from “our constant concern with it for so long.”120

There is no indication in the published writings that the CENIS authors still believed that magic keys to communication power could be easily located. Rather, the path to greater communication “effectiveness”—which is to say, the ability to manipulate an audience to a desired end—was now seen as incremental, with each new bit of insight contributing to a growing understanding of communication behavior. There also appears to have been general agreement among CENIS specialists concerning basic methodological issues such as sampling procedures and data analysis as well as consensus that rough-and-ready methodological shortcuts could be used when surveying hostile or “denied” populations.121

What all this meant as far as the pages of Public Opinion Quarterly were concerned was that the number of articles concerning Soviet communication behavior declined, while the number concerning contested countries in the Third World increased substantially. Leading scholars who had previously been frequent contributors of studies stressing cold war ideological struggles turned instead to a major debate within the profession over the failure of simple “cause-and-effect” models to predict communication behavior.

A 1959 article by W. Phillips Davison, “On the Effects of Communication,” illustrates the dynamics of the new developments at the close of the period covered by this book. Davison was at that time at the RAND Corporation and had recently completed two books on Germany in the cold war, one of which was written with Hans Speier.122

Davison’s essay provides one of the first extended articulations of what was to become the influential “uses and gratifications” approach to communication research. In it, he lays out a series of premises on the interplay between communication and human behavior, contending that all human actions are in some way directed toward the satisfaction of wants or needs. Because human attention is highly selective, individuals sort through the ocean of information that they encounter to find the messages that they believe (rightly or wrongly) will facilitate satisfaction of their needs. The individual’s “habits, attitudes and an accumulated stock of knowledge” serve as “guides to action” during that sorting process. Davison goes on to argue that this framework permits a coherent explanation of a body of communication research data from the previous decade that would otherwise seem anomalous. Further research in psychology and sociology held the promise of revealing the specific mechanisms by which the sorting process works, he concluded.123

One intriguing aspect of Davison’s paper is the conceptual link between this new analysis and the earlier body of psychological warfare research, particularly the unsuccessful search for magic keys to communication effects. Davison specifically rejects “passive audience” conceptions, then readapts the tactics for achieving domination over an audience to his new analysis. Here is how he concludes:

The communicator’s audience is not a passive recipient—it cannot be regarded as a lump of clay to be molded by the master propagandist. Rather … they must get something from the manipulator if he is to get something from them. A bargain is involved. Sometimes, it is true, the manipulator is able to lead his audience into a bad bargain.… But audiences, too, can drive a hard bargain. Many communicators who have been widely disregarded or misunderstood know that to their cost.124

The audience, then, is not passive; it might rather be seen as an unruly animal that must be tamed in order to extract a desired behavior. The underlying similarity of both the “old” and “new” constructions, however, is the urgency attached to discovering methods for the more effective subordination of the target audience to the will of the “communicator,” and the absence of inquiry into the relationship between the communicator and political, economic, and military powers of his (or her) society. In both instances, the social context of communication is stripped away, not simply as a temporary measure to carry out a particular experiment in a controlled environment, but instead as a basic aspect of the theory itself. As Davison articulated it in 1959, communication again implicitly reduces to a collection of techniques for a “manipulator”—his word—this time explained with references to personal and social psychology.

Davison’s reference points for his argument are drawn largely from the body of psychological warfare operations and studies that had played such a large role in the emergence and professionalization of the discipline. He gives three examples of means by which “communications can lead to adjustive behavior,” two of which are illustrated with examples drawn from World War II psychological warfare.125 Davison’s other proofs in the study, each of which is footnoted, are drawn from the USIA propaganda campaigns in Greece, Lloyd Free and Hadley Cantril’s overseas surveys for the CIA, Cooper and Jahoda’s propaganda studies, debriefings of Soviet defectors, and Kecskemeti, Inkeles, and Bauer’s studies of Soviet propaganda.126

No one can fault Davison for having read and used the literature. The point is that here again, the paradigm of domination in communication left a mark on later mass communication studies not generally remembered as having anything whatever to do with conceptions of U.S. national security, ideological struggles, or the cold war.