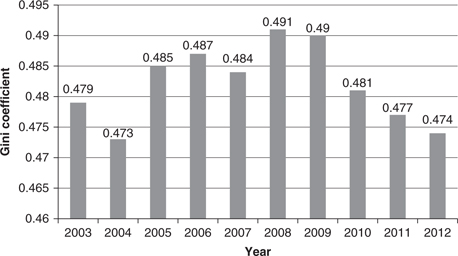

Figure 10.1 Official Gini coefficient estimates for China (2003–2012)

Source: China Daily USA (February 1, 2013)

10

TRENDS IN INCOME INEQUALITY IN CHINA SINCE THE 1950s

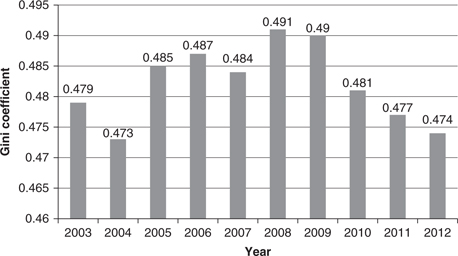

China’s phenomenal economic growth since 1978 has been matched by an equally impressive increase in economic inequality. As one of the most equal societies in the world in the 1970s, China had become perhaps the most unequal country in Asia by 2010. The official Gini coefficient for 2012 was 0.474 but some unofficial estimates were much higher.

During the “collective era” (1950–78), economic inequality declined because of policies that eliminated private property and squeezed public sector wages into a narrow range. However, different dimensions of inequality behaved quite differently. For instance, policies of local self-sufficiency increased inequalities among localities and enterprises. Additionally, the urban–rural income disparity widened because of urban bias in development policy and the population registration (hukou) system.

Post-1978 reforms began in the countryside and reduced the urban–rural gap for several years. Then it widened again to high levels by international comparative standards. However, regional inequality, correctly measured, seems to have increased at first and then fallen back to levels below its starting point.

Since the early years of this century, China’s development model has given rise to growing economic imbalances. These are closely linked with the problem of inequality. The central government has been committed to reducing both; it faces, however, resistance from their entrenched beneficiaries.

The fame of the “Chinese miracle” – the very high economic growth rates achieved by China over a period of more than three decades, which have pulled China up from low income status to make it both a middle income country and an industrial powerhouse – is almost matched by the notoriety of its burgeoning inequality. A country that in 1980 was among the world’s most equal in terms of income distribution changed to the point that by 2010 it was more unequal than most countries in Asia (Table 10.1).

How great is inequality in China? According to the National Bureau of Statistics, China’s Gini coefficient rose to a peak of 0.491 in 2008 and then declined (Figure 10.1) until 2012. Some independent estimates of the Gini range quite a bit higher: the Chinese Household Finance Survey Center of Southwestern University (Chengdu, China) has put it as high as 0.61, which is in a class with the highest Ginis anywhere, those for parts of South America and southern Africa.1 On the other hand, the China Household Income Project, an ongoing international research project that periodically surveys household income in urban and rural China, has estimated the Gini for 2007 (its most recent survey round) as 0.483, almost identical to the official estimate for that year.2

| Country | Gini coefficient |

| Vietnam | 0.376 |

| India | 0.368 |

| Sri Lanka | 0.403 |

| Philippines | 0.44 |

| Bangladesh | 0.31 |

| Pakistan | 0.327 |

| China | 0.474 |

Source: UNDP, Human Development Report, 2011

Notes: Except for China, the Gini coefficients are from the most recent year available (2000–11). China’s is for 2012, and is taken from Table 10.2, below (see below also for a discussion of the Gini measure of inequality)

High incomes are well hidden and thus under-sampled in China. If such concealed high incomes could be included, the estimated Gini might rise by as much as four percentage points (Li and Luo 2011). Thus, the “real” Gini for China is a matter of contention or, at least, uncertainty. However, while estimates of its absolute value vary widely, there is widespread agreement that the trend of inequality has been mostly upward since the mid-1980s.

The balance of this chapter discusses the changes in China’s income distribution and the roots of these changes in China’s development model. We treat economic inequality primarily in terms of income. This is not an inevitable choice: other worthy candidates for attention include, inter alia, consumption, education, access to health care and other keys to a better life, and political rights. In the 1950s, for instance, a highly egalitarian income distribution masked substantial inequalities in political power that produced abusive treatment of ordinary people by government officials or Communist Party cadres. Such political inequality helps to explain the severity of China’s 1959–61 famine, which left ordinary people – mainly rural residents – without recourse when misguided policies pushed their food supply below subsistence level. Despite substantial equality in income distribution, then, great inequality in the crucial dimension of political power could be said to have been responsible for millions of famine deaths.

Figure 10.1 Official Gini coefficient estimates for China (2003–2012)

Source: China Daily USA (February 1, 2013)

Health care is another component of well-being not adequately represented by income. The World Health Report of the year 2000, the World Health Organization (WHO) focused critically on inequality of health care in China, ranking that country as low as 188 out of 191 countries in “fairness of financial contribution” (India is ranked 42). The report was critical of the fact that Chinese paid 75 percent of health care expenses privately out of pocket. China was also ranked 144 in overall health system performance, well below India’s rank of 112. Yet China’s rank for health status was 81 (India, 134) and for distribution of health, 101 (India, 153). How did China’s unfair and low performing health system somehow manage to produce a much healthier population than that of other countries with fairer and better performing systems? There are undoubtedly inequities and inefficiencies in the Chinese health care system, but these may have been overstated in the World Health Report, at least in international comparative terms.

The degree of inequality of income distribution is conventionally measured in several ways. The Gini coefficient is the most common measure. It is a single number summary of the Lorenz Curve, which maps the entire distribution of something over all individuals in the population that have it (if it’s a stock) or receive it (if a flow). A chief virtue of the Gini coefficient is that it conveys an intuitive idea of the extent of inequality: the Gini ranges from zero (for total equality of distribution) to one (total inequality). A country with a Gini of 0.25 has relative income equality, while one whose Gini is 0.6 is quite unequal. Also, the Gini is a very widely used measure for China as well as other countries, which facilitates international comparisons. It has a few disadvantages as well: one such disadvantage is the potential for ambiguity, in that it is possible for different Lorenz curves to intersect and two different distributions could thus yield the same Gini coefficient. Moreover, the Gini for a population cannot be directly broken down into Ginis for its constituent parts (say, states or provinces), nor can those of its parts be aggregated to get that of the whole. However, it can be indirectly broken down because of its property that G = Σri Ci, where G is the Gini coefficient of total income (for instance); ri is the ratio of the ith source of income (e.g. wage income) to total income; and Ci is the concentration ratio, or “pseudo-Gini coefficient” of that income source. The concentration ratio measures the distribution of a particular income source over its recipients ranked by their total income, not by their income from only that source.3

Another common measure of inequality is the Theil indexes, instances of a general entropy (GE) index. “Entropy” here refers to the non-randomness of data. Inequality of something’s distribution implies that it is not randomly distributed over a population but is concentrated in a non-random way. The general entropy index includes a parameter, α, which measures the sensitivity of the index to changes in income in different parts of the distribution. When α = 1, the sensitivity is the same throughout the distribution, and this yields the Theil T index:

Where N is the size of the population, yi is per capita income, and ȳ is mean per capita income. The Theil L index is the GE index when α = 0, which is more sensitive to changes in the lower income region of the distribution.4

The Theil indexes have different advantages and disadvantages than the Gini coefficient. Their chief attraction is that they can be broken down directly, allowing one to distinguish how much of total inequality in a population derives from inequality between its sub-groups and how much derives from inequality within those sub-groups. On the other hand, it is not as intuitive as the Gini index: a Theil index value does not immediately signal a high, low or average degree of inequality in a particular population.

To gauge inter-regional income inequality, a good, common, and easily calculated measure is the coefficient of variation of the regional means of income per capita (CV, equal to the standard deviation of regional mean incomes divided by their mean). Of course, this measure ignores inequality within each region (which in China contributes the great bulk of total inequality), being concerned only with dispersion of the regional means. For China, special care must also be taken as to how income per capita is measured. That is because of China’s household registration (hukou) system, which assigns every household a particular location. If people move to another place, their hukou usually does not move with them. Therefore, in an age of large-scale migration, the registered population of a place may differ considerably from the actual resident population. More about this below.

If we divide the decades since 1949 into two segments – the collective era, 1950–78, and the reform era since 1979, then it is fair to say that the first segment was marked by falling income inequality and the second by rising inequality (although the second began with a burst of equalizing changes, see below). Rising equality in the first period followed from the drastic socioeconomic changes that were implemented by the government, led by the Communist Party. These changes leveled income inequalities by eliminating most forms of private property. In the countryside, private ownership of land and capital disappeared by the mid-to-late 1950s, as China went from small peasant farming to large agricultural collectives and then “communes” within a few short years, and the income inequality associated with the distribution of property ownership disappeared with it. In urban China, as well, private enterprise was eliminated by 1957, with former owners transformed into rentiers who received interest payments on their appropriated property for several years until these lapsed in 1966.

The majority of urban residents worked for wages whose structure was set by the state to embody only small differentials. Mao Zedong’s view of socialism did not favor individualism but rather the constant promotion of collective effort and solidarity within farms and factories, a position that generally implied reduced differentials in individual incomes within work units. During the “Great Leap Forward” (1958–60) and “Cultural Revolution decade” (1966–76), when material incentives were distinctly out of favor, workers went for years with no increase in pay. Those at the top of the wage scale eventually retired, while those at the bottom were not promoted, causing the distribution of wages to be increasingly truncated. By the late 1970s, China had one of the world’s most egalitarian income distributions. Yet the aversion to income inequality applied mainly to distribution within local institutions, such as production teams (consisting of neighborhoods within villages) or factories. Distribution among such units, however, was a different story. As Mao repeatedly weakened the central planning system with assaults on bureau-cratism, urban hegemony and the “bourgeoisie” of educated intellectuals, China of necessity devolved into a relatively “self-reliant” structure of quasi-autonomous localities and enterprises.

Substantial differences in income could and did exist among these. Within the countryside, for instance, prosperous villages with fertile, irrigated land, and easy access to urban markets coexisted with poor, remote, and upland ones. Such differentials were based on what economists would consider “rents,” i.e. arbitrary differences in locational characteristics that affect the returns to local resources without providing incentives to work hard, be efficient, acquire skills or exercise entrepreneurship. Such incentives were notably lacking at the end of the collective era.

Another glaring exception to the general egalitarianism of the time was China’s urban–rural income disparity, which was even then quite large compared to that of other developing countries. This is because of two basic and closely related aspects of the Chinese Communist Party and government polices: first, socioeconomic institutions and national development plans were both biased toward urban areas and neglectful of the rural majority of the population. For instance, urban workers and their families enjoyed cradle-to-grave access to many social benefits, including guaranteed employment, subsidized housing, medical care, and education for their children, none of which was available to rural residents. The great bulk of investment spending under the Five-Year Plans was also aimed at urban industry, and very little went to agriculture. As a result, capital accumulation proceeded rapidly in industry, continuously raising labor productivity. By the late 1970s, the ratio of output per worker in industry to that in agriculture had grown to about 8:1, from only about 2.5:1 in the early 1950s. Such wide productivity differentials were bound to be reflected eventually in urban–rural differences in personal incomes.

Second, the imposition of the household registration (hukou) system in the 1950s built a wall separating urban and rural populations. Those with a rural hukou were prohibited from moving to urban areas. This sanction was reinforced by the rationing of food: even if a farmer evaded the prohibition and reached a city in search of a better job (s)he would have no means to acquire food. Without such a constraint, many rural–urban migrants would have taken marginal urban jobs that paid far more than their farming incomes, even if less than the wages of full-status urban residents, and this would have brought down average urban incomes. Moreover, the outflow of labor from agriculture would also have raised rural incomes (in areas with surplus labor, the marginal product of rural labor had fallen below the average product). With lower urban and higher rural incomes, the urban–rural gap – or at least its rate of growth – would have declined. The hukou system effectively blocked the labor mobility that would otherwise have countered the constant increase in urban–rural inequality.

Ironically, one of Mao Zedong’s principal objectives was to reduce the “three great differences” – namely, those between mental and manual labor, worker and peasant, and town and countryside – two of which directly reflect the urban–rural income gap. This goal became a much repeated admonishment of Mao’s last decade, and he took heroic measures to bring it about, most famously by uprooting urban health care facilities during the Cultural Revolution and moving them out to rural areas to serve the needs of peasants. Despite such measures, the urban–rural gap continued to grow. Official statistics for consumption per capita indicate that the relative advantage of the urban over the rural population increased by 27 percent from 1952 to 1975 (Table 10.2). Even during the Cultural Revolution decade – when efforts to reduce it were at their height – it increased by 7.6 percent. Thus, throughout the pre-reform collective era, the income advantage of being a city resident grew. As to the absolute size of the income differential between urban and rural residents, estimates for the late 1970s range from the World Bank’s 2.2:1, excluding all subsidies, up to Thomas Rawski’s 5.9:1, which includes the value of urban subsidies in urban income (World Bank 1983; Rawski 1982).

In sum, the “collective period” of China’s recent economic history, ending in the late 1970s, was characterized by declining inequality of income distribution except for that between urban and rural populations, which grew substantially despite vigorously expressed ideological objections to it by Mao Zedong, and equally vigorous efforts to reduce it. The reason for this is the structure of institutions and policies put in place in the 1950s, which privileged the nonagricultural economy and urban dwellers while walling off the rural population from the possibility of entering the privileged sectors through migration.

| Year | Index |

| 1952 | 100 |

| 1957 | 108 |

| 1965 | 118 |

| 1975 | 127 |

Source: Riskin (1987: 241)

In late 1978 China began the process of economic reform and transition from a weak and decentralized form of central planning to a still evolving combination of market economy with substantial state involvement. The initial stage of this transformation was a basic agrarian reform: dissolution of the rural people’s communes during the first few years of the 1980s and their replacement by family farming, abandonment of the previous insistence upon local self-sufficiency in grain production in favor of the encouragement of diversification and the division of labor; and sharp increases in the prices paid to farmers for grain, cotton, and subsidiary crops. Farm output responded with rapid growth and a shift of resources from low value crops into higher value products (poultry, eggs, fish, pork, fruits, and vegetables, etc.). Together, higher farm prices, increasing output, and higher value products produced a dramatic increase in farm incomes: average per capita real net income of the rural population more than doubled from 1978 to 1984 and, for the first and only time in the history of the People’s Republic, rural per capita incomes grew faster than urban. The official household surveys found that rural income grew by 98 percent from 1978 to 1983, compared to a 47 percent increase in urban income (Riskin 1987: 292–3). Since the farmers were universally poor relative to the urban population, their faster income growth reduced the urban–rural disparity. Ironically, therefore, the era of reform and transition that was to greatly widen income disparities – began by doing the opposite.

By 1985, however, the boom in farm output and incomes had ended. The growth potential from redirecting resources into higher value production and from exploiting farmland capital construction done in the past had been exhausted. Moreover, farm prices stopped rising and various institutional changes reduced production incentives facing farmers (Sicular 1988). Agricultural output and incomes essentially stagnated through the second half of the 1980s (Table 10.3). Yet, real GDP grew by an average annual rate of 9.86 percent between 1984 and 1989, while industrial output increased by 134 percent over those five years. The urban–rural income gap may now have widened once again. The late 1980s were also marked by the Tiananmen crisis of 1989, which severely affected the urban economy. Official survey figures for urban disposable income and rural net income show the gap between them widening from 1.86 in 1985 to 2.2 in 1990.5 But these figures are flawed in several respects, especially in leaving out urban subsidies, which biases the ratio downward, but also in not correcting for urban–rural price differences, which biases it upward.

| Year | Millions of metric tons |

| 1984 | 407.3 |

| 1985 | 379.1 |

| 1986 | 391.5 |

| 1987 | 403.0 |

| 1988 | 394.1 |

| 1989 | 407.5 |

From 1988 to 1995, the State Statistical Bureau (SSB, as China’s National Bureau of Statistics was then called) showed the urban–rural gap increasing from 2.19 to 2.63 (in 1988 prices). However, independent estimates for those years tell a different story, namely, that the gap remained basically the same, measuring 2.42 in 1988 and 2.38 in 1995.6

From the mid 1990s, the urban–rural disparity was influenced by new forces, especially the reform of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which resulted in a 30 percent reduction in public enterprise employment (SOEs and collective enterprises). Altogether, urban public enterprises shed about 50 million workers between 1993 and the end of the decade. These laid-off workers were treated in a variety of ways: some received modest maintenance stipends from their former enterprises or from reemployment centers established by local governments. Others were prematurely retired or found jobs in the informal sector. It is safe to say that few if any avoided a substantial cut in their former incomes. The negative impact of all this on the growth of average urban incomes restrained the increase in the urban–rural gap. Independent estimates of this gap, in constant prices corrected for urban–rural price differences, show the gap growing very little between 1995, when it was 2.24, and 2002, when it was 2.27 (Sicular et al. 2008). However, that slowdown was a temporary byproduct of the SOE reform, and the gap resumed its upward trend when the restructuring had largely concluded, widening more than 20 percent to 2.91 in 2007 (Li et al. 2011).7 However one measures it, the urban–rural income gap in China remains unusually wide by international comparative standards (Knight et al. 2006).

Why is China’s urban–rural income disparity so large in international comparative context? China is by no means the only developing country to have adopted strongly urban-biased policies favoring cities over countryside.8 However, China went farther than other developing countries in adopting a system of population movement control – the hukou system – which placed a high wall between urban and rural China and kept the poorer rural residents from sharing in the benefits of fast economic growth. Still, the great variation in estimates of urban–rural disparity that comes from the choice of precise methods of measurement constitutes a warning: when making international comparisons of income inequality, the results are likely to reflect to some degree differences in measurement methods (e.g. whether regional living costs are taken into account and how rural–urban migrants are treated) rather than differences in inequality.

In China, regional inequality refers to differences among the thirty-one provinces and province-level units (including four large municipalities and five autonomous regions – the two “special administrative regions’ of Hong Kong and Macao are usually omitted because of their special circumstances). Like many large developing countries, China contains substantial regional differences in income and development level. In 2010, Shanghai’s average urban disposable income of 31,838 renminbi was over twice as high as that of Guizhou (14,142 renminbi), while its average rural income exceeded Guizhou’s by more than four times.9 Similar differences occur in social indicators, such as infant mortality and literacy rates (Fan et al. 2011). The fact that industrial development after 1978 was centered in the already more industrialized eastern coastal regions constitutes a prima facie reason to believe that the regional distribution of income became more unequal over time, at least in the earlier stages of the reform period. There was evidence that, while the per capita incomes of all the provinces might have been converging somewhat, the eastern, western and central groups of provinces were growing apart.10 The CHIP project found evidence of over all convergence of regional income per capita by 2002 (Gustafsson et al. 2008). For 2007, they divided their sample into four regional groups: (1) large, province-level metropolitan cities; (2) the eastern region; (3) the central region; and (4) the western region.11 In calculating provincial per capita incomes, they also used prices that reflected differences in cost of living among the regions (“purchasing power parity” or PPP prices). Since cost of living is considerably higher in the richer regions, the use of PPP prices brought about a sharp decline in measured inequality among the regions.

As shown in Table 10.4, there were small increases in regional inequality between 2002 and 2007. A considerable part of regional inequality, however, is due to urban–rural inequality; in general, inequality within regions accounts for most national inequality, and that between regions for less than 12 percent of overall inequality (Li, Luo, and Sicular, 2011).

The significance of regional inequality is further reduced by considering the distorting effect of migration on the measures of regional distribution. We noted above that the regional distribution of actual resident population differs considerably from that of official, registered population, due to the population registration (hukou) system. Thus, the city of Shenzhen had a registered population in the year 2000 of one million but an actual population of seven million (Drysdale 2012), while the poor western province of Guizhou had a registered population of 41.9 million in 2010, a 20 percent overstatement of its actual resident population of only 34.8 million (Li and Gibson 2012). If regional inequality is measured using regional per capita income based on registered population, the figures for poor Guizhou will be underestimated while those for rich Shenzhen will be overestimated, thus greatly exaggerating the gap between them. The CHIP estimates discussed above are not prone to this error as they are based on income surveys, but a large number of studies of regional inequality have used GDP per capita as their main indicator.12 This is sometimes a useful way of defining regional inequality, but if differences in individual well-being are the objective, then personal disposable income, rather than GDP per capita, is the better unit of analysis, especially in China, where household incomes are an uncommonly low fraction of GDP.

Using regional GDP per capita but correcting for the use of registered instead of resident population, Chan and Wang (2008) find that regional income disparities rose significantly in the early 1990s but remained quite stable thereafter, as one indeed might expect from the increasing role of long distance migration. A more recent correction along the same lines, Li and Gibson (2012) cast light on the entire period since the beginning of the reform era in 1978 up until 2010. They find that, properly measured, regional inequality (in terms of GDP per capita) fell for a decade after the reforms began; rose in the early 1990s; and fluctuated thereafter, such that by 2010 it was back to the low levels of 1990 and below the starting point of 1978. By this measure, then, there has been no long-term upward trend of regional inequality. However, it needs to be remembered that GDP is not a good indicator of well-being (nor is it intended to be one), and that other studies, such as the CHIP project, that focus on household income, have indeed found significant increases in such inequality.

| 2002 | 2007 | |

| Large cities | 2.34 | 2.44 |

| Eastern | 1.65 | 1.74 |

| Central | 1.12 | 1.16 |

| Western | 1 | 1 |

There is a widespread consensus that China’s economy became highly unbalanced after the turn of the century in a number of ways: excessive dependence on exports, a high savings rate, heavy manufacturing, large state enterprise monopolies, an under-valued currency, and financial repression (interest rates held below their market value); insufficient domestic consumption demand, services, and labor-intensive small and medium enterprises. Income inequality is closely linked with such imbalances, which have constrained household income relative to corporate and government income, labor incomes relative to those derived from profits, and disfavored poorer interior regions relative to richer coastal ones. The Chinese government, concerned about the potential impact of both imbalance and growing income disparities upon social stability, has tried since the early 2000s to reformulate its approach to development to make it more equitable and pro-poor, more focused on the rural interior and more sensitive to environmental protection, inter alia. Large quantities of central government funding have been spent on improving rural education and public health and providing a safety net for both urban and rural populations. Yet, despite real advances in the well-being of the population as a whole, the vested interests that have grown out of the unbalanced economy – coastal provinces, heavy manufacturing industries, export industries, the banking system, etc. – are powerful and, as of this writing, the central government has not been able, despite over a decade of dedicated effort, to alter China’s unbalanced development model.

At the same time, over thirty years of hyper-growth has finally begun to use up the huge labor surplus with which China began the reform era in the late 1970s. A model in which growth brings upward pressure on wages is more consistent with rebalancing objectives than a surplus labor model giving labor no real bargaining power. A crucial question, moving through the second decade of the twenty-first century, is whether this change in objective conditions, together with the progressive inclinations of China’s central leaders, is enough to bring about a more equitable development model in the face of the vast inequalities that mark Chinese society.

1 This figure, for the year 2010, was reported in <http://english.caixin.com/2012-12-10/100470648.html>.

2 CHIP’s sample households are taken from the larger sample used by the National Bureau of Statistics, so it is perhaps not surprising that their results are similar. However, CHIP uses a definition of income that is closer to international standard practice than the official one. Also, as will be shown below, the CHIP Gini estimate declines considerably when regional price differences are accounted for.

3 The latter would produce the true Gini coefficient for that income source.

4 A good discussion of the different common measures of inequality can be found in the World Bank’s Poverty Manual, ch.6, available at <http://siteresources.worldbank.org/PGLP/Resources/PMch6.pdf>, accessed January 14, 2013.

5 See table for “Per Capita Annual Income and Expenditure Urban and Rural Household”, All China Data Center, at <http://www.chinadataonline.com/member/macroy/macroytshow.asp?code=A0501>, accessed January 14, 2013.

6 See Azizur Rahman Khan and Riskin (2001: 44–5). This report on the China Household Income Survey (CHIP) project, which commissioned surveys of rural and urban incomes in 1988 and 1995 (and later for 2002 and 2007), finds that the SSB understated the urban–rural disparity in 1988 and overstated it in 1995. Many but not all subsidies were included in CHIP’s definition of income, unlike in SSB’s definition. Neither one completely corrected for urban–rural differences in cost of living, although the CHIP study corrected for changes in those costs between 1988 and 1995.

7 These estimates correct for differences in prices between urban and rural areas and among provinces, but not for the migrant population living in cities. Additional adjustment for this further reduces the urban–rural gap by a small amount. See Sicular et al. (2008) and Li et al. (2011).

8 See the classic treatment of this topic, Lipton (1977).

9 These data are from China’s National Bureau of Statistics and are available to consortium members at <http://www.chinadataonline.com/>.

10 This implies that convergence within these groupings exceeded their divergence from each other.

11 CHIP sample sizes tend to be too small at the province level to make meaningful inferences, so grouping the provinces in this way has statistical benefits as well as reflecting a common classification in China.

12 For a list of some of these, see table 2 in Li and Gibson (2012). The CHIP data for 1988 and 1995 lack information about migrants, while the 2002 and 2007 rounds included migrant surveys.

Carter, C. A. (1997) ‘The Urban–Rural Income Gap in China: Implications for Global Food Markets’, American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 79(5): 1410–18.

Chan, K. W. and Wang, M. (2008) ‘Remapping China’s Regional Inequalities, 1990–2006: A New Assessment of de facto and de jure Population Data’, Eurasian Geography and Economics, 49(1): 21–56.

Drysdale, P. (2012) ‘Chinese Regional Income Inequality’, East Asia Forum.

Eastwood, R. and Lipton, M. (2004) ‘Rural and Urban Income Inequality and Poverty: Does Convergence between Sectors Offset Divergence within Them?’, in Inequality, Growth and Poverty in an Era of Liberalization and Globalization, G.A. Cornia (ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fan, S., Kanbur, R., and Zhang, X. (2011) ‘China’s Regional Disparities: Experience and Policy’, Review of Development Finance, (1): 47–56.

Fang, X. and Yu, L. (2012) ‘Government Refuses to Release Gini Coefficient’, Caixin (China Economy and Finance) <http://english.caixin.com/2012-01-18/100349814.html>, accessed January 14, 2013.

Gustafsson, B., Li, S., and Sicular, T. (eds.) (2008) Inequality and Public Policy in China, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Khan, A. R. and Riskin, C. (2001) Inequality and Poverty in China in the Age of Globalization, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Khan, A. R. and Riskin, C. (2005) ‘China’s Household Income and Its Distribution, 1995 and 2002’, China Quarterly, June.

Knight, J., Li, S., and Song, L. (2006) ‘The Rural–Urban Divide and the Evolution of Political Economy in China’, in Boyce, J. K., Cullenberg, S., Pattanaik, P. K., and Pollin, S. (eds.), Human Development in the Era of Globalization: Essays in Honor of Keith B. Griffin, Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Li, C. and Gibson, J. (2012) ‘Rising Regional Income Inequality in China: Fact or Artefact?’, University of Waikato Working Papers in Economics, September.

Li, S. and Luo, C. (2011) ‘Zhongguo shouru chaju jiujing you duo da? (How Unequal is China?)’ Jingji Yanjiu, (4): 68–78.

Li, S., Luo, C., and Sicular, T. (2011) ‘Overview: Income Inequality and Poverty in China, 2002–2007’, CIBC Working Paper Series, University of Western Ontario (2011–2010).

Lipton, M. (1977) Why Poor People Stay Poor: Urban Bias in World Development, London: Maurice Temple Smith.

Rawski, T. G. (1982) ‘The Simple Arithmetic of Chinese Income Distribution’, Keizai Kenkyu, 22, 1.

Riskin, C. (1987) China’s Political Economy: The Quest for Development since 1949, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sicular, T. (1988) ‘Agricultural Planning and Pricing in the Post-Mao Period’, China Quarterly, (116): 671–705.

Sicular, T., Yue, X., and Gustafsson, B. (2008) ‘The Urban–Rural Gap and Income Inequality’, in G. Wan (ed.), Understanding Inequality and Poverty in China: Methods and Applications, Basingstoke, Hants.: Palgrave Macmillan.

UNDP (2011) Human Development Report, 2011, New York: Oxford University Press.

Wei, T. (2013) ‘Index shows wealth gap at alarming level’, China Daily USA, updated 01/19/2013, at <http://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/business/2013-01/19/content_16142627_2.htm>, accessed on February 1, 2013.

Whyte, M. K. (2009) Myth of the Social Volcano: Perceptions of Inequality and Distributive Injustice in Contemporary China, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Wong, C. (2010) ‘Paying for the Harmonious Society’, China Economic Quarterly, June.

World Bank (1983) China: Socialist Economic Development, Washington, DC: World Bank, Annex A, p. 275.