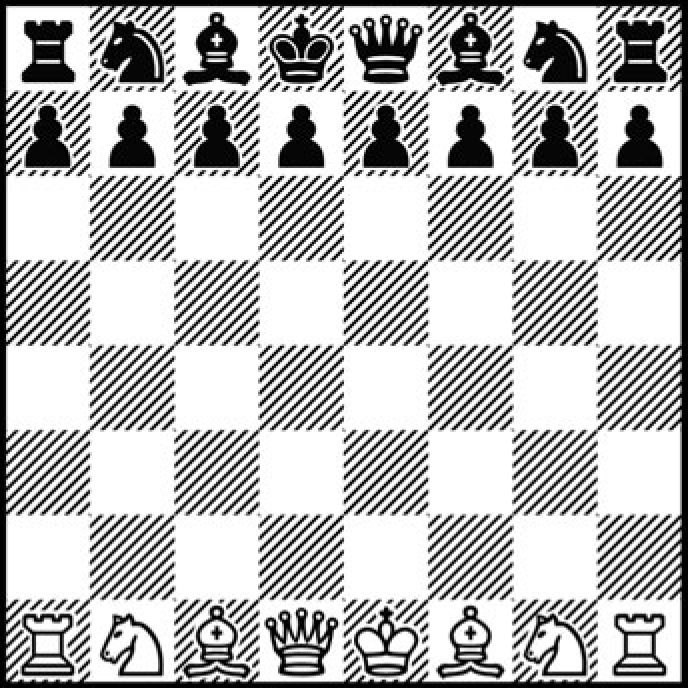

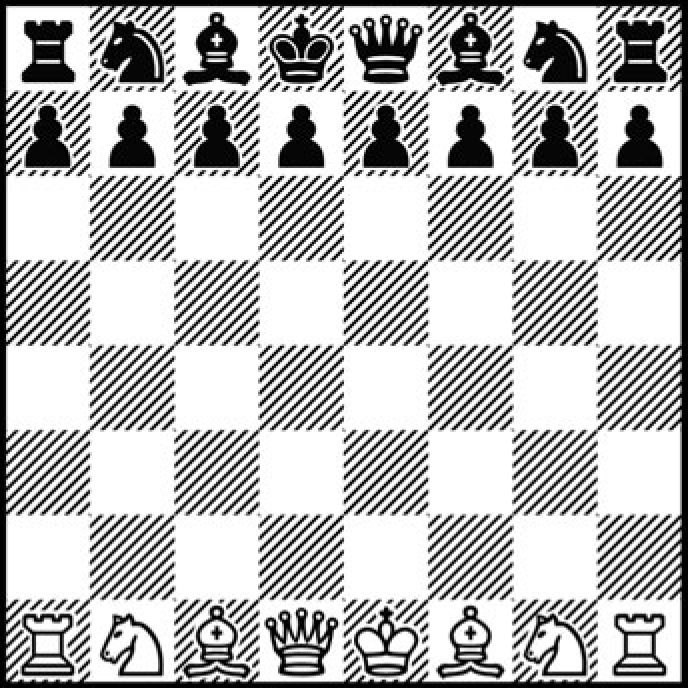

Fig. 9.1

The Irish writer Lord Dunsany was fond of chess. He devised chess problems that convey insight without presupposing anything more than competence at the game. In my favorite problem, White is to play and checkmate in four moves (fig. 9.1). Since Black has all his pawns, he looks far more powerful than White. But something is awry; the black queen is not on a black square as required for the start of a legal chess game. The black king and queen must have moved. That means some of the pawns must have moved. Since pawns can only move forward, the black pawns must have reached their present positions by advancing to the seventh rank. So the only black pieces that can move are the knights. Black has far less liberty than it seems! The white knight can checkmate by first jumping in front of the king, then in front of the queen and finally to either side of the black king for checkmate. Black can only delay the inevitable by one move: he can move his knight to the bishop file.

Fig. 9.1

This inevitability is conditional on White playing rationally. If White dallies, then Black can quickly promote a pawn to queen and finish off White. But in solving chess problems, we are supposed to assume the players are rational and pursuing the aim of the game. The actions of other players are just further instruments of fate.

Time is like chess. Moments proceed by rules. The rules have instructive implications. Consider the Greek mothers who offered sacrifices when they heard that a ship had been lost in battle. They prayed that their sons were not on the sunken ship. For Aristotle, retrospective prayers are futile. In the course of emphasizing that we only deliberate about the future, Aristotle cites the poet Agathon: “Of this power alone is even a god deprived, To make undone whatever has been done.” Either your son was on the ship or not. It is too late for anyone to do anything about it. As Omar Khayyam wrote fourteen hundred years into Aristotle’s future:

The moving finger writes, and having writ,

Moves on; nor all your piety nor wit

shall lure it back to cancel half a line,

Nor all your tears wash out a word of it.

Aristotle contrasted the fixed nature of the past with the openness of the future. No one can bring about a past sea battle, but some people can bring about a future sea battle.

Fatalists deny this asymmetry between the past and the future: Right now, it is either true that there will be a sea battle tomorrow or not. If it is now true that there will be a sea battle tomorrow, then there is nothing that can be done to prevent it. What will be, will be. If it is now false that there will be a sea battle tomorrow, then nothing can be done which will bring about the sea battle. What won’t be, won’t be. For instance, if the admirals order the battle to commence, something will prevent the orders from being executed.

Contemporary commentators on time travel respect the fixity of the past when solving the grandfather paradox. In H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine, an inventor travels into the past and alters history by stepping on a butterfly. Characters in other time travel stories worry constantly about this peril of changing history. They tiptoe through the plot to preserve the established course of events. But if history were so fragile, then a less conservative time traveler could bring about a contradiction. Suppose this revisionist travels back to the days when his grandfather was a boy. He kills his grandfather with a rifle. Since the grandfather never produces a grandson, the shooting undermines a necessary condition of its own occurrence. Since the scenario is contradictory, one may be tempted to conclude that time travel is incompatible with the laws of logic. Defenders of time travel concede that the shooter cannot kill his grandfather. He might pull the trigger, but the bullet will go wide of the mark. Or maybe the bullet hits its mark but the grandfather recovers. Time travelers cannot alter the past because they are already part of the past. Contrary to the novelists, there is no need to tiptoe through the plot to avoid altering the past.

Aristotle’s adversary in this debate is one of his younger contemporaries from Megara, the logician Diodorus Cronus. There is a legend from the Athenian colleges that Diodorus Cronus committed suicide when unable to solve a logic problem set for him by Stilpo in the presence of Ptolemy Soter. Historians mostly value the tale because it helps to date the activities of Diodorus (since Ptolemy conquered Megara in 307 B.C.). It also conveys the stereotype of the Megarians as obsessed with dialectical one-upmanship.

Diodorus was renowned for arguments about the nature of motion. He propounded these in the same spirit as Zeno. However, he is most famous for an argument that Epictetus recounts:

Here, it seems to me, are the points upon which the Master Argument was posed: there is, for these three propositions, a conflict between any two of them taken together and the third; “Every true proposition about the past is necessary. The impossible does not logically follow from the possible. What neither is presently true nor will be so is possible.” Having noticed this conflict, Diodorus used the plausibility of the first two to prove the following: “Nothing is possible which is not presently true and is not to be so in the future.”

(Epictetus 1916, II, 19, 1-4)

Epictetus goes on to describe how some philosophers reject other members of the triad. His presentation is the fully modern one of presenting a paradox as a small set of propositions that are individually plausible but jointly inconsistent. This style of presentation is more economical than characterizing a paradox as an argument. If we count paradoxes in terms of distinct arguments, Diodorus’s three propositions would constitute three paradoxes instead of one.

Although we know the premises and conclusion of Diodorus’s master argument, we do not know the steps that he used in his proof. His contemporaries appear to have conceded that the conclusion follows from the premises. For they try to resist Diodorus by rejecting his premises only. This has stimulated many scholarly attempts to reconstruct the master argument of Diodorus Cronus. Frederick Copleston (1962, 138) suggests the argument went like this:

1. What is possible cannot become impossible.

2. If there are two contradictory alternatives and one has come to pass, then the other is impossible.

3. If the nonoccurring alternative had been possible before, then the impossible would have come out of the possible.

4. Therefore, the nonoccurring alternative was not possible before.

5. Thus, only what is actual is possible.

This interpretation has the advantage of making the argument valid; if the premises are true, the conclusion must be true. But commentators complain that Copleston has left the first premise too easy to deny. Last winter I had it in my power to walk across Walden Pond. Now it is summer and the walk across Walden Pond has become impossible. The change in seasons affects what I have the power to do.

The traditional interpretation of Aristotle’s solution is along these lines: Right now, it is neither true nor false that there will be a sea battle tomorrow. If a sea battle occurs, then the statement will become true. The future is open because statements about upcoming contingencies have no truth-values. In the traditional interpretation, Aristotle concedes that some statements about the future have truth-values. It is true now that “Either there will be a sea battle tomorrow or not” because that exhausts all the possibilities. Aristotle also thought that statements about natural necessities have a truth-value. “There will be a total solar eclipse on August 23, 2044, visible for two minutes in northern Asia” is true because the laws of astronomy dictate it to be true.

The traditional interpretation readily explains why Aristotle never discusses time travel. If the future does not yet exist, one cannot travel from the present to the future. Nor can someone from the future travel to the past. No one discusses time travel until nineteenth-century physicists speculate about time being a fourth dimension.

In 1956, Elizabeth Anscombe challenged the traditional interpretation of Aristotle’s solution. Truth-value gaps for future contingent statements conflict with the principle of bivalence: every proposition is either true or false. Anyone who takes the momentous step of postulating truth-value gaps should be tempted to use these gaps to solve many problems. For instance, the most popular contemporary solution to the sorites paradox is to say that applying a predicate to one of its borderline cases yields a statement that lacks a truth-value. Yet we saw that Aristotle did not make this move when the issue arose as to what specific amount of money marks the transition to avarice. Lastly, Aristotle pioneered the very distinctions and principles that contemporary philosophers use to defuse logical fatalism. They note that, necessarily, either a farmer is a bachelor or is not. But this does not imply that it is either a necessary truth that he is a bachelor or a necessary truth that he is not a bachelor. Similarly, it is a necessary truth that the farmer will reap his corn or that he will not. It does not follow that it is either a necessary truth that the farmer will reap his corn or a necessary truth that he will not.

Many philosophers think that distinctions such as these, codified in Aristotle’s freshly invented modal logic, are enough to disarm the fatalist. We followers of Anscombe think it more likely that Aristotle applied these logical tools rather than momentously breaking with the principle of bivalence.

Diodorus is generally assumed to be a substantive fatalist, that is, a fatalist who believed that time is real. Inspired by Anscombe’s iconoclasm, I challenge this interpretation. Belief in time would grate against Diodorus’s allegiance to the Megarian school of philosophy. As a Parmenidean, Diodorus should believe that time is an illusion. He should not be the kind of fatalist who thinks that the past and future exist and are surprisingly symmetrical aspects of the universe. Diodorus should be a vacuous fatalist who merely thinks that if there is a past and future, then the future is no more open than the past. The point of collapsing all possibilities into what is actually the case is to show the untenability of time and to prove that the existence of the One is a necessary truth. The universe did not just happen to contain exactly one thing. The One is a necessary being that could not have failed to have existed. The appearance of there being many things is necessarily false.

Recall that Parmenides constructed an “as if” theory of physics that could be used to account for appearances. Diodorus was free to construct an “as if” theory of time. Just as Parmenides tidied up his instrumental physics theory by eliminating reference to voids, Diodorus might have tidied up his theory of time by eliminating reference to genuine future alternatives. But Diodorus’s underlying account of time would be that it is an illusion. Unlike a fatalist who believes that time is real, Diodorus need not have counseled people to resign themselves to fate. Diodorus is merely exposing another absurdity in the common belief that there are many things changing through time and the belief that our world is one of many possible worlds. Or so say I.

Aristotle was methodologically and temperamentally receptive to common opinions and the beliefs of experts. He made advances in logic to disarm arguments for paradoxical conclusions. Aristotle was not the sort of man who would follow a syllogism to the death. He feels free to use the conclusion of an argument to judge its soundness. He usually trusts the testimony of the senses. After reviewing the arguments of the followers of Parmenides, Aristotle writes

Reasoning in this way, therefore, they were led to transcend sense-perception, and to disregard it on the ground that “one ought to follow the argument”: and so they assert that the universe is one and immovable. Some of them add that it is infinite, since the limit (if it had one) would be a limit against the void.

There were, then, certain thinkers who, for the reasons we have stated, enunciated views of this kind as their theory of The Truth . . . Moreover, although these opinions appear to follow logically in a dialectical discussion, yet to believe them seems next door to madness when one considers the facts. For indeed no lunatic seems to be so far out of his senses as to suppose that fire and ice are one: it is only between what is right and what seems right from habit, that some people are mad enough to see no difference.

(Aristotle’s Generation and Corruption I, 8, 325a4–23.)

Aristotle thinks you should have the same attitude toward arguments as you do toward clocks. If a clock gives a reading within the bounds of your expectation, then you accept the result. But if the clock gives a reading that seems too high or too low, then you doubt that the clock is functioning properly. In some situations, the clock might be nonetheless right. But you at least have reason to check.

Socrates would reject the analogy between arguments and clocks. Our faculty for reason uses measurements but it is not itself some kind of gauge. Reason is what we use to make sense of gauges. There is nothing further to fall back on. Reason must have the last word.

Since reason compels us to seek what is good and shun what is bad, we have no choice about whether to follow reason. Socrates realized that this ethical determinism makes us sound like slaves to reason. But he presents freedom as determination by what is good. When ignorant, we are determined by our false beliefs about what is good. As we gain knowledge, the objective good determines our will. Knowledge makes us free.

Aristotle thought that Socrates’ ethical determinism flies in the face of the fact that many people are weak willed—and even wittingly wicked. Consider the case of Nathan Leopold. A brilliant son of a millionaire, he was given every educational advantage. He skipped several grades, learned several languages, became an expert on birds, and earned a bachelor of philosophy degree by age eighteen. Leopold was a fatalist who preferred the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche over Socrates. In books such as Beyond Good and Evil Nietzsche extolled supermen who would throw off the chains of “slave morality”: “A great man, a man that nature has built up and invented in a grand style, is colder, harder, less cautious and more free from the fear of public opinion. He does not possess the virtues which are compatible with respectability, and with being respected, nor any of those things which are counted among the virtues of the hard.” Along with his submissive friend Richard Loeb (age eighteen), Leopold (then nineteen) decided to commit the perfect crime. They meticulously planned a murder-kidnap plot. On May 21, 1924, Leopold and Loeb lured fourteen-year-old Bobby Franks into a car and killed him with a chisel. Leopold and Loeb were arrested ten days after the murder. After they confessed, their prospects for avoiding the death penalty seemed remote. They were poor candidates for the insanity defense. Leopold and Loeb were from wealthy, supportive families. Leopold was actively studying law at the University of Chicago! Although Loeb was of only average intelligence, he was a popular, handsome student studying history at the same institution as Leopold. At the trial, these defiant college boys smirked and giggled. Their lawyer, Clarence Darrow, resorted to one of his pet philosophical themes:

Nature is strong and she is pitiless. She works in her own mysterious way, and we are her victims. We have not much to do with it ourselves. Nature takes this job in hand, and we play our parts . . . What had this boy to do with it? He was not his own father; he was not his own mother; he was not his own grandparents. All of this was handed to him. He did not surround himself with governesses and wealth. He did not make himself. And yet he is to be compelled to pay.

(1957, 64–65)

Judge Caverly sentenced Leopold and Loeb to life imprisonment for the murder plus ninety-nine years for kidnapping. Many suspected that Judge Caverly’s sentence was an incoherent compromise between free will and determinism.

If Darrow’s fatalism were correct, Leopold and Loeb were not guilty (even though Darrow had shrewdly counseled them to plead guilty). We are not guilty for acts that we could not have refrained from performing. Consequently, Leopold and Loeb would have no basis to feel remorse for killing Bobby Franks. Clarence Darrow could not consistently maintain that Judge Caverly ought to spare Leopold and Loeb. Judge Caverly was determined to sentence the killers to death or determined not to.

In ancient Greece, there was a popular story about the founder of Stoicism, Zeno of Citium (not to be confused with Zeno of Elea). He beat his slave for stealing. The slave, something of a philosopher himself, protested: “But it was fated that I should steal.” “And that I should beat you,” retorted Zeno.

Darrow had also used science to support his fatalism. The whole methodology of psychology seemed to demand the kind of deterministic outlook later articulated by the behaviorist B. F. Skinner: “If we are to use the methods of science in the field of human affairs, we must assume that behavior is lawful and determined. We must expect to discover that what a man does is the result of specifiable conditions and that once these conditions have been discovered, we can anticipate and to some extent determine his actions.” (1953, 6) The psychologists were preceded by the historians in their demand for determinism. Oswald Spengler presented his Decline of the West as a “venture of predetermining history.”

According to Karl Marx’s historical materialism, the outcome of history is fixed by unalterable economic forces. But if resistance is futile, then isn’t compliance superfluous? Marxism as a political philosophy involved a call to struggle. Why bother? Since Marxism is both a historical theory and a moral theory, the conflict between freewill and determinism is internalized within it.

Christianity incorporates the same conflict. As author of all creation, God foresees everything that will happen from the beginning of time. Yet people must be assigned enough freewill to make them accountable. People must be the appropriate recipients of the rewards of heaven and the punishments of hell.

If there is a genuine conflict between determinism and freewill, then it is not clear that determinism can win. Whenever we deliberate, we presuppose that we are free to choose between genuine alternatives. If you are persuaded that only one outcome is possible, then you cannot try to decide which outcome to bring about. Since we cannot stop deliberating, we cannot shake the belief that we are free. There is no choice about whether to believe in free choice.

Proof that we are compelled to believe that we are free is not proof that we are free. However, it does limit the feasible resolutions of the paradox of determinism. We do not have the same practical compulsion to believe determinism. Indeed, we are receptive to evidence against causal determinism. Thanks to quantum mechanics, many physicists (rightly or wrongly) believe that there is objective chance in the universe. Since these austere physicists think they can get along on a lean diet of statistics, psychologists and historians come off as gluttons when demanding determinism as a transcendental precondition for their own fields.

Aristotle worried that fatalistic belief would induce lethargy. In De Fato, Cicero (106–43 B.C.) formulated this concern as the “idle argument”:

If the statement “You will recover from that illness” has been true from all eternity, you will recover whether you call in a doctor or do not; and similarly if the statement “You will recover from that illness” has been false from all eternity, you will not recover whether you call a doctor or not . . . therefore, there is no point in calling a doctor.

(1960, 225)

The Stoic Chrysippus argued that you are just as fated to call the doctor as you are fated to recover. “Condestinate” facts depend on one another. If you had not called the doctor, you would not have recovered. But there is no possibility of your not calling the doctor. The fatalist should concede that your actions and decisions are causes. Chrysippus’s point is that the choices are not between real alternatives. What actually happens is the only ways things could possibly happen.

As a Stoic, Chrysippus defended moral responsibility from metaphysical attacks. In the next chapter, we shall see Chrysippus marshal a second resourceful defense of morality against a very different metaphysical paradox.