“For the Service of the Province”: The Provincial Sloop Brunswicker and Littoral Defence

The June 27, 1812, headline of the New Brunswick Royal Gazette could not have been clearer: “WAR! WAR! WAR!” it read, and detailed how the news had arrived from the border. Tremors of war had long been felt in the Loyalist colony. Now that it was here, how would it be conducted? As it turned out, few pitched battles were fought in the Bay of Fundy and adjacent waters; instead, the local experience can best be classified as low-intensity warfare, in which force is applied selectively and with restraint. Along with military force, each side might attempt to subvert the other through economic and political means. A hallmark of low-intensity warfare is the driving of military decisions by political objectives. As the German military philosopher Karl von Clausewitz wrote, “The political object, as the original motive of the war, should be the standard for determining both the aim of the military force and also the amount of effort to be made.”

In this instance, both the US and British governments chose to make the Bay of Fundy and the New England coast a secondary theatre and to focus their main efforts elsewhere. Regular units were small, and they exercised restraint to an almost painful degree. For example, the US commander of Fort Sullivan, which overlooked the boundary between Maine and New Brunswick, was forbidden from firing on Royal Navy warships as they passed up Passamaquoddy Bay. The British warships for their part always lowered their colours when passing the battery, making it clear that they did not intend to attack.

In such a low-intensity conflict, acts of magnanimity were as important as acts of violence for the forces involved. Paroling prisoners of war, returning trunks to captured sailors, and even conducting elaborate funerals for fallen enemies were common in the region. The British admiral in charge of the Halifax station, Herbert Sawyer, quickly grasped this concept, and knowing that the New England states were largely opposed to the war, did his utmost to facilitate an illicit trade with willing US merchants and refused to blockade the New England coast. He did not have enough ships on hand to carry the war to the enemy in any case.

The type of war fought in New Brunswick’s waters early in the war was also a form of low-level conflict known as guerre de course (hunting warfare). In general, the point of guerre de course was to capture the enemy’s merchant shipping and protect one’s own, thereby hindering the enemy’s economy and supply chain while defending friendly cargo vessels. It was fought by small naval vessels acting alone, or by privateers — privately owned vessels licensed by government to attack enemy shipping. Irregular units, such as militia or privateersmen, were also a part of this small-scale warfare, but, without major ideological or cultural differences, their primary activities revolved around the acquisition or defence of property and were relatively bloodless.

This guerre de course was fought in the littoral, or near-coastal, environment of the Bay of Fundy. It was not just a matter of operating in coastal waters, though; sea forces also came ashore to skirmish, and sometimes land units took to small craft to engage with naval units or privateers. US privateersmen fully embraced the littoral warfare concept in that they were more likely to go ashore in search of plunder, despite its clear illegality. In June 1813, for example, the US privateer Weasel raided homes in Beaver Harbour, New Brunswick, taking not only trade goods but also household furniture and even women’s and children’s clothing. These privateersmen also had few scruples about plundering an American farmer of his chickens one night — perhaps a case of over-identifying with the name of their boat. Charlotte County’s militia went in pursuit of the Weasel in three boats, chased the Yankees ashore at Grand Manan Island and rescued the stolen property.

As the Weasel incident indicates, the vessels involved in this littoral warfare were usually small — sometimes mere open boats, but more often two-masted schooners or brigs, with only the occasional British frigate appearing on the scene. As a rule, the larger the warship, the less time it spent in littoral operations. That said, the bigger vessels tended to create much greater panic among the coastal populace, not so much because of their larger batteries, but because they carried smaller boats or barges with which to comb coastal waters for prizes or launch shore raids.

Yankee Privateers

The most common US units operating in the Bay of Fundy were privateers from ports such as Gloucester or Salem, Massachusetts. While the owners and officers of these vessels saw the war as an opportunity to make money, they also tended to have ideological motivations based on their adherence to Jeffersonian ideals of equality, territorial aggrandizement, and a dislike of all things British. Ill-disciplined amateurs, they often violated the magnanimous approach regular military and naval officers displayed. Many such privateers immediately sailed for the approaches to the Bay of Fundy on hearing the news of the declaration of war. Their goal was to capture British and colonial shipping coming out of St. Andrews and Saint John.

A typical example of the Yankee privateers that harassed New Brunswick shipping was the chebacco boat1 Fame, a modern replica of which currently operates as a commercial charter vessel. The replica’s captain, Michael Rutstein, author of a thoroughly researched and very accessible book about the original’s career entitled Fame: The Salem Privateer, concludes that the twenty-five men who joined together to man the Fame in 1812 were modest sea captains, merchants, and shipowners who could not afford to be without work but were not rich enough to invest in privateers while remaining safely at home. When war appeared imminent, they pooled their resources to purchase a fast, recently built fishing schooner. The Fame was about fifty feet long with a broad bow and a pointed “pink” stern;2 she carried two small cannon and a crew of up to thirty. On July 1, 1812, the owners having received a privateering commission, the Fame set sail for her chosen hunting grounds in the Bay of Fundy. New Brunswickers had known about the war for less than seventy-two hours. As Rutstein relates,

It didn’t take long for Fame to hit the jackpot. In a few days she was off Grand Manan, on the border between the United States and Canada, and fell in with the ship Concord of Plymouth, England, and the Scottish brig Elbe. Both vessels surrendered without firing a shot. Fame was back in port by July 9th, just eight days after setting out, and her prizes arrived a few days later. Concord, with her cargo of masts, spars, staves, and lumber, and Elbe with tar, staves and spars, were condemned as legitimate prizes and sold at auction. The net proceeds were $4,690.67 — nearly ten times what Fame had cost!

The problem for New Brunswick was that the Fame was but one of many such Yankee privateers that swarmed the Bay of Fundy. The Fame herself would venture forth on no less than twelve cruises before being wrecked on the Seal Islands off Nova Scotia in spring 1814.

Privateers mostly were a nuisance rather than a real threat, but in the early days of the war they made some significant captures. For example, the tiny Salem privateer Madison, armed with just one cannon, captured a British transport brig bound for Saint John with a cargo of gunpowder, 880 sets of uniforms for the 104th (New Brunswick) Regiment of Foot, and camp equipment and band instruments. In this instance, Britain’s loss was America’s gain, and the 104th’s uniforms clothed drummers and musicians in the US military.

The Royal Navy was stretched thin at the beginning of the war, but its response was rapid, using both convoys and cruising as tactics to engage the enemy’s smaller vessels in the Bay of Fundy. Occasionally, larger ships, such as frigates, would attempt to sweep the coast free of troublesome raiders as well, but by and large this was a war conducted by lesser vessels.

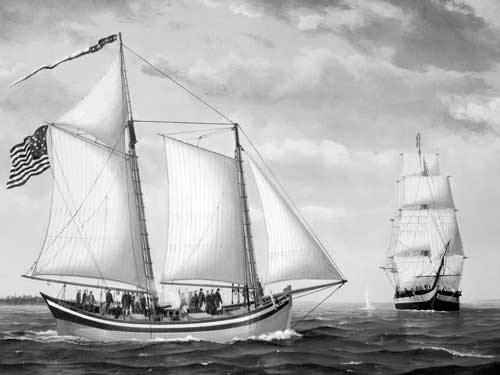

Convoys in the Bay of Fundy typically gathered at Saint John and picked up more vessels off Campobello Island. The escorting ships were usually sloops-of-war, gun brigs, or schooners. Most officers did not like convoy duty, which could be tedious and frequently meant arguments with commercial shipmasters. Furthermore, the region’s extensive fogs often made it impossible to see the flags used in the Royal Navy’s complex signalling system. The potential advantage for naval officers was that convoy duty presented an ideal opportunity to impress seamen.

With cruising, on the other hand, officers could use their own initiative to pursue and capture enemy shipping or privateers and receive prize money. In fighting the privateers, British naval officers quickly learned to disguise their vessels in order to lure US ships closer. Commander Henry Jane of H.M.S. Indian painted one side of his vessel black and dirtied the other side, rearranged the ship’s boats, unsquared the yards,3 and flew an American flag in order to look like a harmless merchant vessel. The ruse worked well enough to capture at least one US merchant brig.

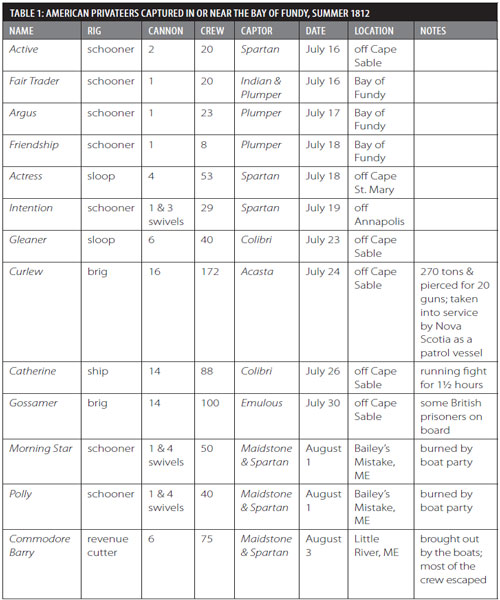

In the summer of 1812, panic began to set in among Americans around the Bay of Fundy. At the beginning of August, the frigates Maidstone and Spartan briefly entered the bay and aggressively hunted down Yankee privateers, even launching raids on US harbours. The results were good, and a number of US privateers were captured (see Table 1). Yet there always seemed to be more of these irksome craft to replace their losses. Indeed, in the opening weeks of the war, despite the Royal Navy’s efforts, New Brunswick’s leadership was worried by the many US privateers operating in the bay. The region’s newspapers complained that US privateers were “swarming around our coast, and in the Bay of Fundy; hardly a day passes but hear of captures made by them.”

Source: Based largely on the report of Vice-Admiral Herbert Sawyer to the Admiralty, August 25, 1812, reproduced in London Gazette, September 22, 1812.

Anxious to protect local commerce, Governor George Stracey Smyth and his council agreed that New Brunswick should acquire an armed vessel to protect shipping in the bay. On July 5, 1812 — just one week after news of war reached the colony — the Executive Council authorized the purchase of a vessel to defend New Brunswick against US privateers. A suitable craft was soon found in the Commodore Barry, a captured US revenue cutter that had been pierced for ten guns but that was carrying just six when taken. The schooner was named after John Barry, an Irish-born naval officer who served in the Continental Navy during the American Revolution and was the first officer commissioned in the US Navy when it was created in 1794. The US government purchased the schooner at Sag Harbor, New York, for $4,100 and stationed it at Passamaquoddy, Maine, under the command of Daniel Elliott, an experienced seaman who moved vigorously to suppress smuggling across the Maine-New Brunswick border.

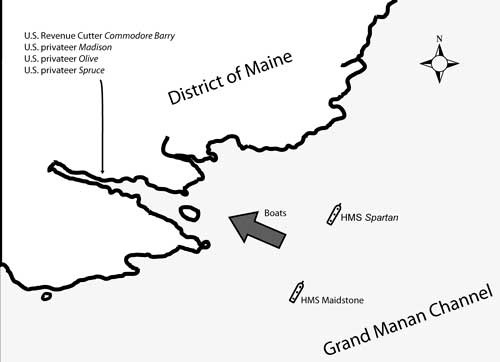

The war was only a few weeks old when Elliott and his command, along with the American privateer Madison, found themselves bottled up in Little River, a narrow cove in eastern Maine. Outside lay four British warships, including the two frigates dispatched to the Bay of Fundy to sweep up the troublesome Yankee privateers that were interfering with local shipping. Battle was not long in coming, and it was to combine the elements of land and shore combat so common to littoral warfare. The Commodore Barry, in company with the small privateers Madison, Olive, and Spruce had no escape route. The Yankees therefore hauled their vessels close to shore and hastily built a “battery of cord wood” from which to defend the vessels. This “battery” was probably no more than a pile of firewood hastily rearranged to shelter US sailors as they fired their muskets. The British attacked on August 3 in five barges containing about two hundred and fifty sailors and Royal Marines from H.M.S. Indian, Plumper, Spartan, and Maidstone. It was the standard sort of skirmish the Royal Navy had become quite good at, often referred to “cutting out expeditions” or “boat parties.” Such cutting out attacks were among the hardest-fought engagements of the War of 1812, but younger officers were keen on them because they offered relief from the tedium of patrol, blockade, and convoy, the opportunity to acquire prize money from captured vessels, and a chance to be noticed by their superiors and perhaps gain promotion.

One such midshipman was twenty-year-old Frederick Marryat of H.M.S. Spartan, who commanded a boat that helped to cut out the Commodore Barry. After the war, Marryat became one of the earliest novelists to work within the sea story genre, and wrote a number of best sellers, including Mr. Midshipman Easy, published in 1836. He essentially created the format that followed a midshipman through his sailing career, making him the precursor to twentieth-century novelists such as C.S. Forester, Patrick O’Brian, and their imitators. Marryat, however, was not the only aspiring author on board H.M.S. Spartan: her commander, Captain Edward Pelham Brenton, wrote a popular mammoth multi-volume Naval History of Great Britain from the Year 1783 to 1822, published in 1823.

Accounts of the skirmish are conflicting and fragmentary. The local community heard heavy gunfire for about two hours before the British overwhelmed the Americans, who had probably run short of ammunition. US newspapers claimed that, after a “severe contest, in which a number of the English were said to be killed,” the crews of both the cutter and the privateer escaped because they “took to the woods” to avoid capture. Three of the Commodore Barry’s crew, however, were taken when Captain Brenton sent a detachment of ten Royal Marines to secure the revenue cutter. The British then burned the privateer Madison and took the Commodore Barry and the other two privateers to Saint John. On Thursday, August 6, Spartan and Maidstone arrived in Saint John harbour with seven prizes, including the two privateers and the revenue cutter. The American prisoners of war were landed and imprisoned in the city’s jail. One can imagine that the city’s populace was well pleased with the captures.

The Provincial Sloop Brunswicker

When the captured Commodore Barry entered Saint John harbour, merchants William Pagan, Hugh Johnstone, and Nehemiah Merritt immediately recognized that the vessel was well-suited for the colony’s needs. Not much is known about her appearance, let alone why she attracted the merchants’ attention. She was not a large vessel — certainly less than one hundred tons displacement. When in US service, she apparently had been rigged first as a schooner, but records in New Brunswick and elsewhere always refer to her as a sloop.4 It seems likely she was re-rigged as a single-masted vessel at some point before her capture, a fairly common transition in the age of sail. Her small size was probably attractive to her economy-minded purchasers because she would require a smaller crew. She was fully equipped and armed, although the details of her armament remain unknown. She also likely was built a little more substantially than the captured privateers then in harbour, which probably were no more than converted fishing schooners. As a matter of practicality, the vessel was also immediately available.

But there was a problem: while the United States had declared war on Britain, formal British recognition of the state of war did not yet exist, and so Nova Scotia’s Vice-Admiralty Court, which handled all prize cases, could not formally condemn the vessel and sell her. Such legal formalities would not be allowed to stand in the way of colonial defence needs, however, so on August 8 the three merchants created an informal agreement whereby the Royal Navy officers would receive £1,250, in return for which the officers promised that their agent would steer the paperwork through the Vice-Admiralty Court and hand the sloop over “for the service of the Province.” Included in the price were all its guns, ammunition, stores, provisions, boats, and everything else on board.

Initially, Governor Smyth refused to purchase the sloop for the colony, but within days, as his anxiety about American privateers increased, he purchased the “revenue cutter prize sloop” for the same price Pagan, Johnstone, and Merritt had paid for her. She was soon renamed Brunswicker to reflect her intended role in defending the colony’s shipping. On August 20, the colonial government advertised in the Saint John newspapers for a contractor willing to supply provisions for its new sloop.

The sloop was quickly put in operational order and remained busy for the rest of 1812. Her mission was always defensive: to protect local shipping in the Bay of Fundy primarily by acting as an escort vessel. In mid-August, the colony provided instructions and a strict admonition that on no occasion was Brunswicker to go west of Passamaquoddy Bay unless in actual pursuit of an enemy vessel. Despite these instructions, Brunswicker made one cruise as far west as Mount Desert Island in the company of H.M. brig Plumper to rescue British-flagged vessels that had been captured by US privateers. Then, in September, the governor and council received a letter from Plumper’s commander urging that Brunswicker be released to cruise as far west as Mount Desert:

From undoubted information which I have received, and from recent orders which have fallen into my hands from the late captures I have made, I learn that the enemy’s cruisers in general direct their prizes to make Mount Desert, where I had the good fortune to re-capture the three British vessels I brought into port, and had I the smallest assistance to take care of these I had in possession, I might have taken seven more; but the small privateers are so numerous that I could not quit my prizes. I was therefore under the painful necessity of allowing the enemy to pass unnoticed. There are at present from fifteen to twenty privateers out of Portland, Salem, and Boston, cruising on the Eastern coast of Nova Scotia, most of whom will be returning the latter end of this month; until then the coast will remain clear for their prizes to get in, as I can hear of no British cruisers in the Bay. I have therefore to request that His Honor the President would allow the Brunswicker to accompany His Majesty’s brig under my command for a few days to Mount Desert, when, I have no doubt, we should intercept many British vessels getting into the enemy’s ports before the Admiral has time to send a sufficient force there, of which I shall apprise him of the necessity without loss of time.

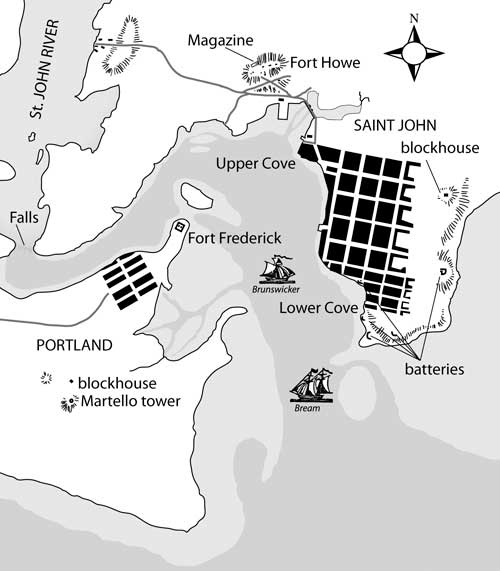

The council immediately recommended the employment of thirty or more additional hands, not exceeding fifty in the whole, on board Brunswicker to accompany Plumper on this service. A month later, the sloop again joined Plumper in escorting a convoy of fourteen merchant ships from Saint John to Halifax. In November, Brunswicker accompanied H.M. schooner Bream in quest of two US privateers said to be off Point Lepreau, chasing them off but failing to capture them. More than twenty seamen belonging to different ships in Saint John harbour and several local citizens volunteered their services on board Brunswicker for this duty.

In December, Brunswicker, again in company with Bream, had the grim task of salvaging the wreck of Plumper, which, on the morning of December 5, had been caught in a snowstorm in the Bay of Fundy as it made its way from Halifax to Saint John and wrecked on rocks near Dipper Harbour, in Charlotte County. About half the people on board, including two female passengers, died. Two officers, including its commander, and twenty eight of the crew survived the ordeal and got ashore; some were taken aboard Brunswicker and transported to Saint John a few days later. On board Plumper was some $60,000 in silver Spanish dollars, the pay for New Brunswick’s military garrison, so Brunswicker remained near the wreck for some weeks to guard it while salvors rescued $32,440 from the deep.

Despite this activity, the early months of 1813 saw the colonial government debating the value of the sloop. Governor Smyth told the council in January that he was convinced US forces would attack New Brunswick before spring. He regarded Brunswicker as a crucial element in the colony’s defence and asked the council to authorize £500 to fund her operations for four months. The council agreed, but somewhat reluctantly. Beverly Robinson, in particular, worried about the utility of the vessel, which he called “paultry.” Others thought that the vessel could aid in the defence of St. Andrews, although Robinson observed that the vessel’s two 9-pounder cannon and 12-pound carronades provided little real firepower. Chief Justice Jonathan Bliss took a lighter view, jesting that, if Brunswicker went to St. Andrews, perhaps she should be insured so the colony could turn a profit if she were captured. Despite the jokes about insurance, Brunswicker visited St. Andrews by the end of January before returning to Saint John, and returned to Passamaquoddy Bay in early March.

Brunswicker’s Officers and Crew

Brunswicker’s commander for most of its career in provincial service was a mariner named James Reed, born in Saint John in 1784 to English parents who had settled in New Brunswick before the Loyalist migration. Reed went to sea as a young man and eventually became a ship’s master, sailing principally between Saint John and ports in Britain. He was active in Saint John’s social life as a member of the Freemasons and participated as an officer in a special volunteer militia unit designated as “sea fencibles” — militia who could serve either ashore or afloat. His background was ideal for his duties as commander of the armed sloop.

Much less is known about the rest of the crew — sailors in the age of sail are a notoriously difficult group to track — but some details can be gleaned from a document in the New Brunswick Provincial Archives that lists the crew (see Table 2). The officers were mostly from Saint John, and it seems likely that they were Reed’s friends or family — the second mate, in particular, was probably his son or a nephew. The gunner was not a seaman but a soldier from the Royal Artillery who received additional pay to serve on board Brunswicker and train her crew in the use of the cannon. The cook, Samuel Bagley, was black, and Richard Smith might have been as well. Both were illiterate, signing with a mark rather than a signature, as did seamen Robert Filler and Andrew Roark. The regular crew sometimes was joined by volunteers known as “supernumeraries,” who rounded out the ship’s complement when Reed anticipated combat. These were probably young local men who signed up for perhaps a week on a lark, serving for free except for provisions and the possibility of prize money. A week’s service on board a tiny vessel in the dead of winter was probably more than enough for most volunteers, who undoubtedly were glad to return to hearth and home after their little adventure.

Source: Provincial Archives of New Brunswick, Sessional Records (RS24) S23-R10.13.

Although the sloop’s officers and crew were not in the military or naval service, they did operate under strict ship’s articles — a sort of contract that bound seamen to the master of a vessel. A copy of Brunswicker’s articles in the Provincial Archives of New Brunswick details the obligation of the crew to follow orders, not go ashore on pain of forfeiting their wages, and abide by the officers’ rule for the “suppression of vice and immorality.”

The bills generated by Brunswicker, also preserved in the Provincial Archives, offer some clues about life on board the vessel, especially diet. The food seems to have consisted entirely of fresh beef and ship’s biscuit, or hardtack. Other grocery items included coffee, sugar, water, and, of course, rum. This basic diet was considerably less varied than that of the Royal Navy, which also provided peas, cheese, and cocoa on a regular basis. But no mention is made of any sort of vegetable, not even potatoes, on board Brunswicker. It is possible that, since the vessel spent much of the time in port, her crew was able to supplement their diet while ashore, and almost certainly they tried their luck with hook and line to catch fish.

Brunswicker’s bills also indicate that the vessel needed repairs in early 1813. On the advice of some maritime gentlemen, including a Lieutenant Hare of the Royal Navy (of whom we shall hear more in the next chapter), colonial officials agreed to “fill in the waist” of the sloop, which probably involved replacing an open railing, and within a few weeks Saint John shipwrights had built a solid cedar bulwark on board. The choice of cedar is surprising, since, when hit by a cannonball, it was notoriously prone to splintering, sending a shower of shrapnel-like shards that could maim or kill those nearby.

Bills, however, were Brunswicker’s undoing. The expense of running the vessel was prohibitive: from August 1812 until January 2, 1813, it exceeded £771, a serious drain on the colony’s finances. When, on January 21, Governor Smyth announced that the Crown would bear the cost no longer, the colonial legislature balked at assuming the responsibility and resolved that the sloop should be discharged from service since there was now a sufficient Royal Navy presence to protect local shipping. Smyth, who had been heavily censured by the Colonial Office in London for having taken the vessel into service, was in no position to disagree. According to the Vice-Admiralty Court records now in Ottawa, Brunswicker was laid up in May 1813 and remained in Saint John harbour for a further two years under the care of a shipkeeper, stripped of its sails and much of its rigging. Mostly, she sat at a mooring, where she was pumped out occasionally and had her sails aired.

Ironically, Brunswicker was deactivated just as panic over US privateers swept Saint John. In early May, word arrived that an American privateer was skulking outside the harbour, but there were no British naval vessels in the vicinity. Rather than reactivate Brunswicker, Saint John merchants took over the Salem privateer Cossack, which had been launched just that spring and captured between Grand Manan Island and West Quoddy Light on its first cruise by H.M. sloop Emulous and taken to Saint John for adjudication. A schooner of only forty-eight tons, she boasted but one cannon, a long 18-pounder. After her capture, she sat at a wharf in Saint John with her sails stripped from her and placed in a warehouse. Alarmed by rumours of nearby privateers, local merchants prevailed on officials to release the vessel to guard the harbour. Sailors re-rigged the privateer’s sails, and arrangements were made for soldiers of the Saint John garrison to embark on the schooner as marines. James Reid offered to command the vessel, an entirely logical choice given his experience. The US threat soon passed, however, and the vessel remained anchored in the harbour. On his return to Saint John, the commander of Emulous was displeased to see “his” prize vessel ready to get under way and took the schooner to Halifax without notifying anyone, sparking a court case in Nova Scotia’s Vice-Admiralty Court.

For the remainder of the war, the business of defending New Brunswick’s trade and coasts fell once again on the heavily burdened shoulders of the Royal Navy. The colony was extraordinarily lucky that the young officer most associated with that duty not only was unusually willing but also able to carry out that mission.

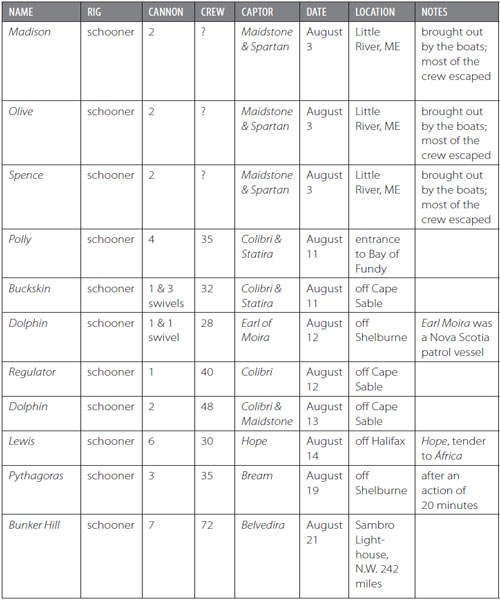

Salem privateers such as the Fame captured many vessels sailing out of Saint John. Captain Michael Rutstein, http://www.schoonerfame.com

A convoy signals book, circa 1812; the region’s frequent fogs often rendered the system ineffective. NARA RG 21, “Records of the District Courts of the United States, Southern District of New York”

US naval officer John Barry, namesake of the revenue cutter Commodore Barry. LC-H261 2945

Cutting out the Commodore Barry in Little River, Maine, August 1812. Joshua M. Smith

Council member Beverly Robinson , who called Brunswicker “paultry.” NBM W6726

“View of the Town of St. Andrew’s with its magnificent Harbour and Bay,” ca. 1840. Coloured lithograph by William Day (Day and Son Lithographers) after a sketch by Frederick Wells. LAC C-016386

Governor George Stracey Smyth. LAC C-011221

Saint John, circa late 1812. Its fortifications, however, were in poor repair or, in the case of the Martello Tower, not yet constructed. Joshua M. Smith, based on W.O. 55/860, p. 422

Bream in combat with the American privateer Pythagoras, 1812. MM