INJURIES: THE FIVE STAGES OF GRIEF

By Dimity

By Dimity

The pain started about mid-June. Little pinpricks would light up across the top of my right foot after a run. It was a novel pain, delicate and interesting, but not debilitating. I kept going; I had my eyes on the 2010 New York City Marathon. Within a few weeks, the pinpricks turned to lightning bolts, which struck most intensely when I wore my silver flip-flops post-run. Some people would stop wearing the shoes, but I loved those silver flip-flops, which matched everything and were trendy—another novelty for my hard-to-fit feet. So I wore them and pretended I wasn’t being shocked with each step. By early August, my foot felt like a Fourth of July night sky. Still, I kept running, albeit for shorter distances. I also switched shoes, tried to change my form, walked barefoot when I walked our dogs to encourage my feet to return to their natural state, and wished the pain would simply decide one day to disappear. Because, you know, running injuries typically do that.

Having lived in my body for almost 40 years, though, I knew better. While procrastinating during the day, I’d Google “top of foot pain” and “running”—I didn’t want to put the words stress fracture into the universe, even though I was 90 percent sure that was what I was dealing with—and click on links until I’d see those dreaded two words and immediately close the window. Not only was I in an empire state of mind, I also had a couple of running commitments (pacing my ultrarunning friend Katie for about 11 miles in the Leadville Trail 100, pacing my pal Pip in a 5K) that I simply couldn’t stomach missing. Unlike my first stress fracture three years prior, which was in my left heel and which I couldn’t ignore unless I was lying flat on my back, this one was less intense. The fireworks eventually settled into a constant bee sting that, while far from comfortable, wasn’t unbearable.

“In a 5K, every step was painful. I felt like I was running grueling 15-minute miles; shin splints had taken over. I recovered with ice packs and chiropractic care.”

—MEGAN (Worst night before a race: sharing a bed with her sideways-sleeping, kicking son.)

“My SI joint flared up a mile away from home, and I couldn’t bear weight through my leg. I am a physical therapist, so I lay down in the road and attempted to correct it, but I couldn’t fix it without assistance. I had to hobble home, and it took 2 weeks to recover. My husband jokes the only reason I became a PT was to treat my own injuries.”

—CHRISTY (Proudest running moment: making state all 4 years in high school track.)

“I had hairline fractures in both shins, but it took awhile to get a diagnosis. I ran a 21-mile run on the fractures but was unable to complete marathon training. Now I get new shoes every 400 miles, and I don’t push myself beyond my limits.”

—COURTNEY (Next on her running list of things to do: speedwork.)

“Yes. In the weeks leading up to my first half-marathon, I was having extreme leg and hip pain. The elliptical didn’t seem to aggravate it, so I did that. I survived the race, but could barely walk 15 minutes later.”

—MELISSA (Compulsive about ending her runs on a whole number. “I’ll run a lap around a parking lot to make sure I don’t end at 6.95 miles.”)

“No. I’ve had two stress fractures, and during the first one, I realized I could crosstrain. So when it happened again, I knew there were other things I could do, and it would feel so much better to get out there when it’s fully healed.”

—TRACY (Started running after her third daughter was stillborn. “I needed a way to channel my emotions.”)

“I developed tendonitis in my ankle from running on uneven snow. My PT had me run without shoes and set a metronome to speed up my turnover, and my stride evened out. He treated the tendonitis, and I started running in Saucony Kinvaras at 180 steps per minute. Totally changed my running.”

—KIM (Found her BRF when a woman stopped her car and got out and asked to talk to her during a run. “I thought she wanted directions, but she wanted a running partner.”)

But it wasn’t going away, and after I ran next to my friends—I didn’t tell either until we were in the thick of the races, because I didn’t want them to worry about me—I knew I had to really stop. An X-ray and examination confirmed what I already knew: I was officially injured. When the orthopedist said I’d have to wear a boot and sent his nurse to get one, I said I already had one. Although I had wanted to toss that black monstrosity after stress fracture numero uno, I had buried it in a far-flung closet in case I needed it for a Halloween costume. That night, I asked Grant to get it for me, and as soon as I saw it, I got the feeling of having a piece of dry toast stuck in my throat. I could hardly breathe.

I was already weary of the late-August, mid-90s temperatures, and knowing I had to clomp around in a hot, hefty boot for 6 weeks was simply too much. My breathing returned, but the tears started pouring. I Velcro’d on the inner boot, which was festooned with dog hair and tiny balls of lint, and through sobs, I fastened on the clompy part that would keep my foot still enough to heal. I kept the Frankenfoot on for the better part of 7 weeks. I pushed the gas pedal with it; I went camping wearing it; I wore it out to dinner on date night. (The doc told me to sleep in it. No. Just no.)

As I went through the 5-month ordeal, I realized I was living the five steps of grief, a process of dealing with death that was introduced by psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross in her 1969 book, On Death and Dying. I wasn’t grieving in the most despondent sense—my family was healthy, my husband and I were employed, there was no imminent tragedy—but a running injury is much more traumatic than the physical ailment. For most of us, running is so much more than the act of putting one foot in front of the other. It’s an elixir for self-definition, empowerment, endorphins, strength, deep thoughts, joy, and confidence. Take away my run, and my life does a seismic shift in the wrong direction.

Bearing that in mind—and to validate your feelings next time you’re knocked out—I present to you the five stages of running-injury grief.

You’re in this stage if: Your thought about your IT band syndrome, shin splints, or other malady is that it truly isn’t a problem. “It doesn’t really hurt when I stand this way,” you tell yourself, shifting all your weight to the noninjured side. “When I run only on trails and not more than 2 miles every third day, I’m totally fine,” you say to a friend. “Totally fine.”

In other words, you don’t accept you’re hurt—or are on your way to being the sidelined kind of injured—so you keep running and tweaking your form in search of the pain-free run. In defense of our often delusional brains, it could be very likely that the new state of pain or your compromised gait is the only reality you know. As I’ve described too many times, I had piercing pain in my left hip and glute for almost 3 years, and it just became a way of life: I put on my jeans sitting on the bed so I didn’t have to balance on my gimpy left leg.

Once the pain makes itself undeniably known or a doctor gives you a get-real diagnosis, you realize something has to give. But you can’t conceive of a life without running: How are you ever going to get to (or afford) the gym? And if you do get there, what are you going to do? Get on the elliptical and stare at somebody’s back for an hour? Ugh.

True Stage 1 example: Flying with SBS last spring, I noticed she hobbled like a rodeo cowboy as we deplaned together. I didn’t think this 1-APH walk was fodder for a joke, so I asked if she was okay. “Yeah, it’s just my ankle and heel,” said Sarah, always an optimist. “Doesn’t that happen to you when you’ve been sitting for a long time?” I chose not to answer because, no, I don’t usually look like I need a skycap with a wheelchair when I get off an airplane.

Two days later, she ran a half-marathon, then finally allowed herself to accept that her case of plantar fasciitis was nastier than she wanted it to be, and that the only way to kill that sucker was to take a break from her beloved sport. (BTW, if jealousy were part of the stages, it would enter in here for me: In 28 years of running, that was the first injury-related break she’s ever had to take. Yeah, I know. You can be jealous, too.)

You’re in this stage if: Your mood can best be described as bitchy, crabby, or irate. You might be pissed at your running friends. You guys were all training for the same half-marathon, using the exact, down-to-the-very-last-step plan. How can all three of them still be running happy while you’re sitting in a doctor’s waiting room? Or, at the gas station, you might shoot a scowl at some random stranger who is wearing a pair of running shoes and a Lycra-infused outfit that indicates he might have logged some miles in the last few hours.

Chances are, though, your loved ones are the ones in your bull’s-eye; just as kids can be perfect for a babysitter and have a total meltdown when you step one foot inside the door, you can put on a brave face for the world and peel off the plastic when you’re at home. You may be snippy to your husband, who simply does not get why taking something, especially something physically taxing, off your to-do list is grounds for such self-pity. And when he splurges to surprise you and cheer you up with dinner from the Whole Foods prepared-food section, you’re incredulous. “Really? Häagen-Dazs peanut butter and chocolate ice cream for dessert? Why don’t you just paste it right on my thighs?”

While you’re likely more compassionate toward your children, your normal level of patience has left the building. “Didn’t I tell you to pick up your backpack?” you bellow twice in a 30-second span at your child, who just walked in the door from school and beelined to the bathroom.

You might even get angry with your own body. You may step on the scale more times than is healthy, or decide that today is the day you’re going to nail the one-hundred-push-up program, but because you can’t run, and crave sweat and burn, you opt to start on Day 14, not Day 1.

True Stage 2 example: Like your body getting used to the feeling your IT band is as tightly strung as the shortest string on a harp, your mood can get so used to this emotional state that it simply always surrounds you, like the dirt perpetually engulfing Pig-Pen. I could write entire novels about how I take out my frustration on my family (and likely make you feel better about your actions), but suffice it to say, I am not always the nice person I appear to be in public.

After an MRI revealed two bulging discs and a severely arthritic back—yet another hash mark in my injury column—the doctor suggested I try Pilates. I did, and about a year later, at approximately the same time of night I would’ve likely been pissed at Grant because he had, once again, forgotten to put out the recycling and garbage, I asked him if he thought I was standing taller. His response to that question was lukewarm, but then he added, “But you haven’t complained about your body and how much it hurts in months. That’s worth so much, I’d subsidize Pilates for the rest of your life.” (Please note: He speaks well, but he has not yet subsidized any of my Pilates. I pay for that out of my own account, not our joint funds.)

Unlike running injuries, where we tend to ignore our limits (“Oh, this piercing pain in my glute isn’t anything”), we know our boundaries when it comes to doling out advice about injuries. We are far from being physical therapists or doctors, yet we know that injuries are squirrely little suckers. Out-of-whack hips, an overambitious stride, or roughly 736 other factors can cause an angry knee.

So we asked Janet Hamilton, an excellent exercise physiologist and running coach, the author of Running Strong & Injury Free, and the mother to two golden retrievers, to help define the most common causes and cures for widespread injuries. Please note: The cures work only if you actually ice, stretch, do your strength work, scale back your miles, and so forth—and not just read about doing so.

What it feels like: Tenderness on or alongside the shin bone

How you got them: Ramping up your mileage too fast, going a little overboard at the track, or some combo thereof; excessive pronation, or your feet rolling inward when you land; inadequate hip strength and core strength; worn-out shoes, or a sudden change to shoes with less support than you’re used to.

What can help: Ice; gentle and frequent stretching of the calf muscles; orthotics if needed (either over-the-counter or prescription); scaling back your miles and avoiding hills until you feel better; hip-strengthening exercises, especially lunges in all directions (forward, backward, side to side).

What it feels like: The area above your heel and behind your anklebones is tender and sore. The soreness can sneak up on you, and if you catch it before it becomes more pronounced, you can save yourself months of rehab.

How you got it: Wearing shoes that don’t give you the amount of support you need (could be that there’s either too little, or too much, guidance); supertight calves; weak hips (we don’t blame you; we blame the kids you carried); not being smart about increasing your training intensity (you deserve a little blame here).

What can help: Icing after running, orthotics, eccentric exercises like heel drops,1 dramatically scaling back your runs, or taking breaks. Heel lifts, used in both shoes, might provide temporary relief, but don’t rely on them long term.

What it feels like: A pain in the bottom of the heel or in the arch, which is most apparent either first thing in the morning or when you stand up from being seated. It usually gets better as you move around.

How you got it: Calf muscles are wound tighter than your boss; your shoes don’t have enough support; going too far or too fast without giving your body time to catch up; making a sudden change in terrain, speed, footwear, or running form.

What can help: Rolling a golf or tennis ball, or a frozen water bottle, under your foot for 10 to 15 minutes once or twice a day; wearing a resting night splint or specially designed strap that keeps your foot flexed overnight; gently but frequently stretching your calves; getting in the right shoes with the right amount of support for you; backing off the mileage and intensity work, as well as hills; and working on hip strength. (Yep, note the theme: The butt is connected to the foot.)

What it feels like: A pain in the outside of your knee and possibly in the lower thigh.

How you got it: Excessive pronation; weak hips and glutes; tight calves, hamstrings, or quads.

What can help: Strengthening your hips (Google “clamshell exercise for hips” to find a demonstration); stretching tight calves or hamstrings; self-massage with a foam roller or other device; new shoes; massage.

What it feels like: A whiny knee, which is felt most acutely after a run; when you sit for long periods of time (driving 2 hours to Grandma’s house or sitting through a movie); or when you go up and down stairs.

How you got it: Inadequate hip strength (yes, that culprit again!); feet that pronate too far and aren’t being supported with the right type of footwear; tight hamstrings and calves.

What can help: Strengthening your hips and quads; stretching; ice; orthotics or a change in footwear; a great sports massage (yeah, we know: as if you have the time—or funds—for it).

What it feels like: Localized bruiselike pain on a bone that causes you to wince when you push on it; it may hurt even at rest.

How you got it: Biomechanical issues; low bone-mineral density; underfueling; ramping up mileage or intensity too quickly; sudden changes in terrain, footwear, or gait pattern; inadequate rest.

What can help: Time off to let the bone heal (expect between 6 to 8 weeks); crosstraining if you have no pain in the injured area; focused strength training that can help support the area when you do get back to running.

You’re in this stage if: All your thoughts with regard to running and your injury involve an if/then statement.

True Stage 3 example: Sarah’s plantar fasciitis had an acute onset: During her final pre-race track workout, within the first few steps of her sixth 800-meter repeat, it was as if she had stepped on a metal spike that drove up into her right heel. A half-marathon was a mere five days away. Never having been injured before—like I said, total envy is expected and normal—she was unsure how it would all play out. Her more immediate concern was how she’d get home: Putting any pressure on her right foot was excruciating. Visions of crawling the half-mile home filled her head; she debated whether she could hobble home like a three-legged dog. After much teeth gnashing and many deep breaths, she was able to stand upright and limp along the sidewalk. Her usual 5-minute jaunt took nearly 20 minutes.

Delusional and in deep denial, she thought maybe it would be serviceable by race day. Her first vow was to not run on it again until the race. (If I don’t run on it until race day, then it’ll be just fine!) In the next few days, as she began to grasp the scope of the problem, her mind scrambled with bargains. The one she kept coming back to: “If I can make it through the race without hearing—or feeling—a big ‘pop’ or ‘snap,’ then I’ll take time off.” After asking a race official the protocol for dropping out midrace in the point-to-point course, Sarah unwisely covered the 13.1 miles. Adrenaline must have masked the pain, which she ranked at a 2 or 3 during the race; moments after the finish line, it shot up to a 9. It took the two us nearly as long to return to our hotel (.4 miles from the start) as it did for her to run the course, and the grimace on her face far outshone her finisher’s medal.

You’re in this stage if: You have completely and totally given in to your injury—and given up on being active. It’s hard to remember why running brought you any pleasure. When you see a runner on the road, you’re no longer angry with them. Instead, you just think they’re wasting their time. “Why bother if you’re only going to get injured?” you think.

If you’ve been prescribed certain physical therapy exercises to help you heal, you do them half as often as you’re supposed to. Or maybe you don’t even do that. Your foam roller is collecting dust. You may bail on some massage or acupuncture appointments, since your improvement seems so minor compared with the cash you’re laying out. Any thoughts of sneaking into your race, if you had one on the horizon, are definitely squelched. You sleep in more than you know you should, shower less than you know you should, and watch more shows on Bravo while consuming more Dove Bars than you know you should.

True Stage 4 example: I should be sponsored by Kleenex based on the number of boxes I’ve gone through while crying about running injuries. Most of those tears were shed solo. As in I wasn’t even talking to anybody. I was simply sad and alone, and I couldn’t get my run on to not feel so sad and alone.

A certain patina settled over me when I hit this stage of my second round of boot wearing. Things were different. The first time, I was able to keep training on the bike (here) and run the 2007 Nike Women’s Marathon 6 weeks after removing the boot. The second time, I didn’t have the mojo to spend the equivalent of at least a cumulative week on the bike to run another marathon. So I had no prize to eye. Because I wasn’t really sweating, and because the boot was a pain to disassemble, I minimized my showers. The circles under my eyes must have been unusually murky, because when I met SBS in San Francisco to speak, ironically, at the 2010 Nike Women’s Marathon, our first stop was at Benefit to get me some makeup, including under-eye concealer. What’s more, I felt fat—and should’ve, given how I was eating. A huge bowl of leftover Annie’s Mac & Cheese, two pieces of toast covered in butter, and three chocolate chip cookies is a good lunch for a sedentary person, right?

You’re in this stage if: You start setting your alarm for 5:30 and get up 4 days a week, just so you’re ready to rock when your body is ready to roll. Or when your kids settle into Good Luck Charlie, you settle into 20 minutes of clamshell and other less-than-scintillating but very necessary physical-therapy exercises. You start to look up shorter races 5 months away on Active.com, and picture yourself running one of them with no issues. As you begin to eat small crumbs of improvement, you start to encourage others who might be in one of the stages in your rearview mirror.

True Stage 5 example: After seeing a sports-medicine doctor and a podiatrist, and forgoing running completely for a month and a half, SBS fully embraced the full panoply of treatments for her foot. Any cure she read on the Internet, she did. She had acupuncture treatments, religiously took Aleve every morning and evening, rolled her foot on a frozen water bottle several times a day, wore only orthopedically correct footwear, slept in a Strassburg Sock, wore a copper-infused compression brace, and stretched her foot for several minutes before stepping out of bed every morning. She did the “trace the alphabet with your foot” drill so many times, I’m betting her foot writing is easier to read than her 6-year-olds’ handwriting.

Despite her diligence, recovery took far longer than she ever would have anticipated when she was struck lame that mid-May morning. Her twins finished their final month of kindergarten, enjoyed their summer vacation, and were filling their backpacks with back-to-school supplies by the time Sarah felt she could say with any certainty that her plantar fasciitis had been tamed into true submission. But she’d learned to accept she had joined the ranks of injured runners—and had, at least once, experienced the five stages of grief that accompany injury.

“You made it to the start. You will make it to the finish.”

—AMANDA (Her family members position themselves a bit before the finish, so they will see her coming in strong without a lot of people in the way.)

“Keep running. People are watching.”

—LISA (During family fun runs, sticks with her husband until the last half-mile, when she completely blows him away.)

“Do or do not. There is no try. —Yoda”

—KATIE (Removes her shoes to run in socks if her feet start hurting.)

“Lisa #26372: Donnie Wahlberg is waiting at the finish line naked with crab sauce and cannoli cake.”

—LISA (Named her basement treadmill Donnie Wahlberg because “It’s fun to get on him and get a workout.”)

“In front of a church: ‘Is there a patron saint of blisters?’ and ‘Even atheists pray at mile 24.’”

—PATTY (Has run two “huge” PRs in the two races she wore her “Badass Mother Runner” shirt—which are available at anothermotherrunner.com . . . just sayin’.)

“Hello complete stranger. I’m so proud of you.”

—STEPHANIE (Looks forward to Tuesday-night dates with the TV [to watch Glee] and treadmill [to do speedwork].)

“Pain is temporary. Your time will be posted on the Internet forever!”

—DANIELLE (On training runs, has an iPod on her arm, headlamp on her head, reflective vest with a rear light attached, and pepper spray in her hand. Plus, house key and phone. “I’m trying to figure out what I’m going to do when I start doing longer runs and need water and GUs. I should bring the wagon.”)

“That hill is your bitch.”

—AMANDA (Introvert or extrovert on race day? “I smack strangers on the ass. If it looks really good, I’ll grab.”)

“My sister held a sign once in the Chicago half-marathon: ‘Hurry up! I’m FREEZING!’”

—SUSAN (Loves hearing “Go Mom!” during a race. “I’ll feed off that even if it’s not my family.”)

“DID YOU POOP?”

—DARCY (Coincidentally, happens to have poop anxiety. “I MUST poop before a race.”)

“No, you’re not close, but you’re doing great!”

—TINA (Loves the trails around her Chico, California, home, but avoids them in the summer because of buzz worms, aka rattlesnakes.)

“ F—— this, let’s go bowling!”

—AMY (While on a run saw a lady walking a guinea pig. “It had a little harness and everything.”)

“Go, Mom! (What’s for dinner?)”

—PHOEBE (Saw the sign during a half-marathon on Mother’s Day eve.)

By Dimity

When I suffered a stress fracture in my heel about a third of the way through training for the 2007 Nike Women’s Marathon, I wasn’t ready to quit. I attached my road bike to a trainer and took a trial spin in the basement. My heel didn’t hurt. Phew. So I kept training with guidance from a super-resourceful coach, Ivana Bisaro of Carmichael Training Systems.

Since I crossed that finish line, I’ve probably fielded at least a hundred questions about how I trained for a marathon on a bike—my longest run was 16 miles, pre-marathon—and the answer I always give is, “I worked really hard.” I don’t consciously hold back specifics; it’s just that the details are too complicated to fit in a neat, verbal package. And, to be honest, I don’t remember them all that well.

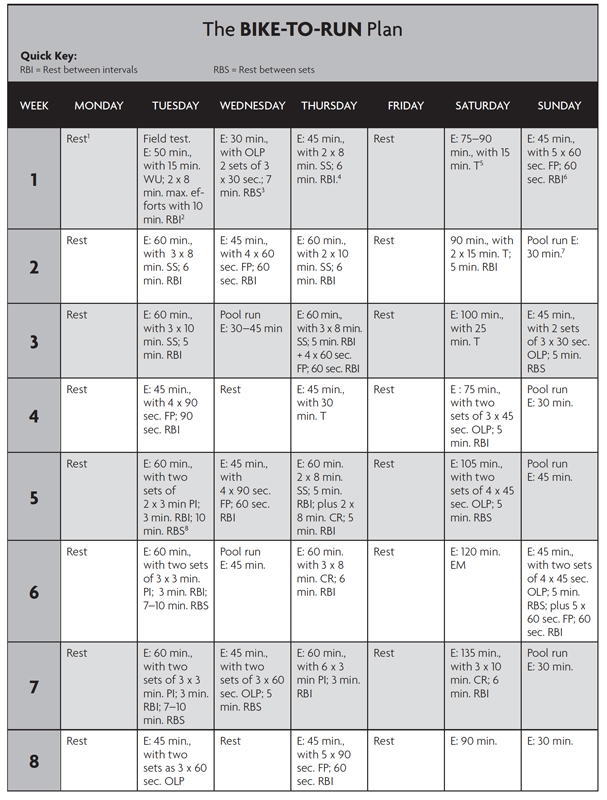

But they fit in this book just fine, so I asked Ivana, who is now a mom to three kids, to grace us with her bike-to-run training knowledge for a runner who is injured during half-marathon training and doesn’t want to hang it up. (If you’re gunning for a marathon, extend the longer rides on the weekends to the amount of time you’d be running long.)

A few caveats from somebody who has done this before: This is not an easy plan. Be prepared, as I did, to work. Hard. Chances are, it will actually improve your cardiovascular fitness, as it did mine. And it looks complicated, but once you get the hang of things, it’s not so confusing. Best of all, this sucker is ridiculously effective. I maintained my sweat-laced sanity, healed my heel, and headed off to San Francisco with fresh legs and a newly rekindled love of running. Oh, and I ran a PR on a crazy hilly course.

What you need: A heart rate monitor; a road bike with a trainer that attaches to its back wheel (trainer is available at REI or bike stores) or access to a spinning bike (not a recumbent or traditional exercise bike, but one that puts you in a true cycling position); pedals on either style of bike with either cages or clip-in capability—the latter is preferred.

Optional equipment: A $50 iTunes gift card, a new book to listen to, or a TiVo with full seasons of your five favorite shows—in other words, you’re going to need some new entertainment; a pool for deep-water running.

With regard to that injury: If your leg, foot, hip, or other injured part hurts when you cycle, you’re out. You can’t get better if it hurts. Even if it doesn’t hurt, do these workouts inside, so you can bail if need be. (Clarification: If your injury, not your heart and lungs, hurt.)

Last bits of advice: Running muscles are not the same as cycling muscles, which your quads may remind you when you hit the bike on the second day. If you haven’t been on a bike since middle school, start conservatively; at most, match your long ride to your long run. Finally, a cadence—or the number of revolutions one pedal has in 1 minute—around 90 has the best carryover to running, but it may be hard to get there if you haven’t been in the saddle in a while. Don’t worry: You’ll be there before you know it.

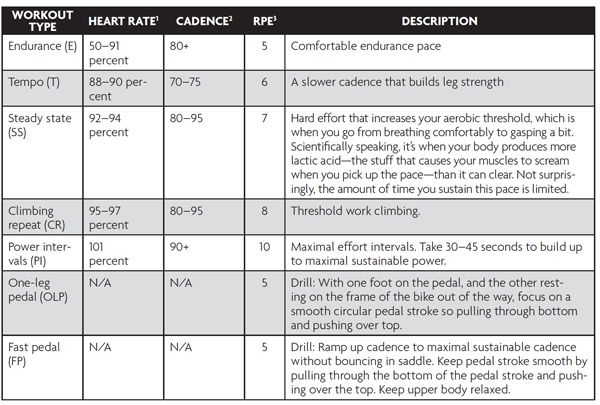

1 These numbers come from your higher average heart rate in the field test, which is on Tuesday of Week 1. To find your ranges, multiply that number by the percentages given. For example, if your average heart rates for the tests were 167 and 170 beats per minute, you’d use 170 to calculate your ranges.

Endurance: 50 to 91 percent

Doing the math: 170 x .50 = 85 bpm

170 x .91 = 154 bpm

2 The number of times your pedals go around in 1 minute. If you don’t have a way to electronically track it, count the number of times one foot goes around in 20 seconds, and multiply it by 3. Check in regularly to make sure you’re on target.

3 A range from 1 to 10, where 1 is an effort equal to sitting and watching your toddler teeter around on his Skuut bike, and 10 is all out chasing after him because he’s about to head down a black diamond–steep hill.

1What it says: Rest.

What you do: Chill, sister.

2What it says: Field test: E: 50 min. with 15 min. WU, 2 x 8 min. max efforts with 10 min. RBI

What you do: Put on a heart rate monitor. Spin easy, building to a moderate pace for 15 minutes. Then begin your field test: Take 45 seconds or so to build into the maximum effort you can hold for 8 minutes. Catch your breath for 10 minutes, then repeat. Record your average heart rate, and use the higher average heart rate to calculate your ranges. Cool down for 10 minutes.

More details: Your effort should be equivalent to a mile time trial at the track. Really push yourself, especially when you hit about 5 minutes down. And don’t think about the second test while you’re doing the first; your body will have plenty of time to recover.

3What it says: E: 30 min., with OLP 2 sets of 3 x 30 sec.; 7 min. RBS

What you do: Warm up for about 10 minutes. Then take one foot out of a pedal (your feet should be secured to the pedal, either with cages on the pedals or clips on cycling shoes) and rest it on the bike frame so that it’s out of the way. Pedal with one foot for 30 seconds. Then switch feet and pedal for 30 seconds. Repeat three times. Take 7 minutes at an endurance pace, then repeat the drill. Finish the ride at an endurance pace, gradually decreasing your effort.

4What it says: E: 45 min., with 2 x 8 min. SS; 6 min. RBI

What you do: Warm up for about 10 minutes, then head into a steady-state interval (92 to 94 percent of your average max heart rate) for 8 minutes. Recover for 6 minutes, then repeat. Cool down with whatever time you have left.

5What it says: E: 75–90 min., with 15 min. T

What you do: Ride in the endurance zone for 75 to 90 minutes. Somewhere in the middle, make your gear harder to reduce your cadence to 70 to 75 for a 15-minute tempo piece (tempo is 88 to 90 percent of your average max heart rate). When you’re done, pop back up to an easier gear and finish your ride.

More details: Netflix or television helps on rides of more than 60 minutes. Just sayin’.

6What it says: E: 45 min., with 5 x 60 sec. FP; 60 sec. RBI

What you do: Pedal in the endurance zone, and when you hit a spot where you want a little variety, make the gear a little easier and pedal as quickly as you can for 60 seconds. You shouldn’t bounce in the saddle, though. Slow down those horses for 60 seconds; repeat five times total, then finish up the ride.

7What it says: Pool run E: 30 min.

What you do: Head to chlorinated waters, jump in, and run in the deep end for 30 minutes. Your options are (not really) endless: You can either stay in one place or travel around the deep end, and you can use a belt or not (beginners might prefer one since a belt positions you properly).

More details: If you don’t have—or can’t stand—this option, you can ride endurance miles or, if your injury lets you, do the elliptical at the gym for the same amount of time.

8What it says: E: 60 min., with two sets of 2 x 3 min. PI; 3 min. RBI; 10 min. RBS

What you do: In the course of a 60-minute endurance ride, crank up the intensity for a 3-minute power interval: You should be going all out, and your heart rate should be above your max average from your field test. Take 3 minutes to recover, then do another 3-minute piece. Pedal easy for 10 minutes, and repeat the whole shebang.

More details: Remember: You can do anything for 3 minutes. Or just about anything.

By Sarah

As anyone who has ever run—or shared a hotel room—with me knows, I am Queen of Oversharing. It seemed only natural to me to carry this over to our Run Like a Mother: The Book Facebook page, so I started posting the occasional too-much-information status updates. Another mother runner named Erica suggested it become a weekly feature, dubbing it TMI Tuesday. A tradition—and a weekly highlight—was born. I culled a few posts and responses that made me laugh, snort, or even blush the most.

“Lawn care” question: Do running shorts and skirts (and swimsuits) make you feel more exposed, causing you to do more bush maintenance during these summer months? If so, what’s your tool of choice—razor, Neet, waxing, other? Don’t we all wish we could run as fast as the hair down there grows?

“My problem currently is trying to ‘mow the lawn’ blindly since I can’t see past my 37-week belly. Terrifying adventure.” —KENDRA

“How short are your skirts?” —LORRAINE

“Project BUSH, my favorite topic. Laser is the way to go. It’s permanent and worth it. If you’ve given birth, laser is nothing.” —KELLY

“I’m definitely a fan of waxing. For a hairy Italian like myself, there really is no better way to manage my forest. The process can be a bit like torture, but I pump on Advil beforehand.” —NICOLE

“I will be looking over all of these responses. My razor makes me look worse than if I had just left it looking like a 1970s porno.” —ALECIA

On our survey for Train Like a Mother, one gal said she skips sex the night before a race to avoid “drippage” during a race (ewww, but true). Anybody else say no to night-before nookie?

“Somehow reading this post makes me think of the song ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit.’ Ha, ha, ha.” —JENNIFER

“Are you kidding? I’ve been married for almost 18 years. I take it whenever I can get it.” —HEATHER

“Yikes! Maybe I shouldn’t be eating breakfast while reading TMI Tuesday!” —EMILY

“Absolutely: I can’t risk throwing my hip out!” —JENNIFER

“After having two babies, half the time I’m leaking with every footfall, anyway, so what’s the difference?” —JENNIFER

“If I want to avoid hearing my husband bitch about having the kids all day while I run, then I had better go ahead and give it up.” —ALECIA

“Agreed: No sex the night before a race, but two nights before, it’s my go-to-sleep aid.” —GINNY

“Girlfriend, lay off the Mucinex!” —STEPHANIE

This truly TMI question came to us via e-mail from a first-time half-marathoner who, post-race, has chafing of the butt crack. Eeek: Get that woman some Butt Paste or Desitin, stat! But the sufferer isn’t looking for a solution, merely solidarity. Please assure her she’s not alone. Anyone, anyone?

“I have a . . . uh . . . . . . friend that this happened to . . . yeah, a friend.” —ANNE

“Oh, yeah, especially in the summer when all the sweat drips down and the cheeks rub together. Lovely! 2toms SportShield is my savior.” —LESLIE

“BodyGlide your crack!” —JUANA

“OMG! This is utterly new to me! What a visual! Glad she is not alone. Can you imagine if you posted this . . . and nothing? Just the sound of cyber crickets chirping. Glad that didn’t happen.” —KRIS

“I have a separate BodyGlide just for that area.” —AMY (Note: Amy later posted a photo of her special-use-only BodyGlide, clearly labeled “ASS.”)

Toot, toot, it’s TMI Tuesday. Here’s the scene: SBS was recently running with a pal who shall remain nameless. She must have had a burrito or beans for din-din, as she was jet-propelled by gas that morning. SBS and the friend stayed mum whenever a gaseous emission was sounded, as if nothing had happened. What do you do when you pass gas while running with a friend, or when your friend toots?

“One of my running friends says, ‘I think I just stepped on a duck,’ and keeps running.” —TERRY

“Definitely make a joke to lighten it up: Accuse her of having an unfair advantage.” —DONNA

“Awkward. That’s why I run alone.” —AMELIA

“Although air may be passed, not a word is.” —HEIDI

“We like to comment on the infestation of barking spiders.” —KOURTNEY

“I giggle and tell my pards to stay upwind for their own safety.” —EMMA

“Oh my, I am laughing so hard at some of the comments that I farted.” —MARIANNE

1 Stand on a step on the balls of both feet, weight balanced, then press up so your heels are above the step. Then shift all your weight to your injured leg, and slowly lower the heel so it is even with the step. Do 10 to 25, and incrementally allow your heel to drop below the step.

2 We deliberately put this in the injury chapter for two reasons: First, for comic relief. Second, for inspiration, in case you’re up for being a spectator and helping others get through their races.