Wheatley and Christopher Lee had become friends since that first meeting in Harrods, and it was Lee who urged Wheatley’s books on Hammer producer Anthony Hinds. Hinds loathed Wheatley’s work, but he saw its potential, and in due course The Devil Rides Out became Hammer’s greatest film.

It was directed by Terence Fisher, who was completely in tune with Wheatley’s vision: Fisher’s work has been described as embodying a strictly dualistic universe, split between Good and Evil, Light and Dark, Spirit and Matter, and expressed in images of “bourgeois splendour” versus “decay and death”.

Satanism was a taboo subject for the cinema of the time, sailing too close to blasphemy1. In the event, no one need have worried; The Devil Rides Out is a highly moral tale, where light and darkness battle and the forces of light win. After the film was made, a Catholic bishop came up to Lee on the street near Cadogan Square and told him he and his “flock” had been much impressed, because “in the end … Evil is vanquished and Good triumphs.”

The first screenplay, by John Hunter, was rejected as too English, and Hinds then commissioned another from Richard Matheson. Matheson stayed close to Wheatley’s plot, and his work largely consisted of streamlining. The political and historical situation in the book is lost, with no Talisman of Set and no risk of world war. Simon is no longer Jewish, and it is a cross, not a swastika, that is placed around his neck to protect him before it is removed and he escapes again towards Mocata, making the incident closer to the Dracula scene which was probably its inspiration in the first place.

Mocata is no longer half-Irish and half-French; instead he is a menacing pinstriped English gentleman with a carnation in his buttonhole, magnificently played by Charles Gray, who had read Wheatley’s books when young. Gray is also well known as the Bond villain Blofeld, and the voice of The Rocky Horror Show, but he never did anything better than play the urbanely evil Mocata.

The drama unfolds in a strangely abstracted mid-century England, a dreamlike place where vintage cars chase each other along endless back-projected country roads with not a modern house in sight. Whether we are being shown the astrological observatory at Simon’s house, or the occult siege at Cardinal’s Folly (a half-timbered house in true Hammer style, with two sphinxes flanking the front door), we are doubly cocooned in the magic of Wheatley and Hammer together. The film has deservedly classic status, not least for “a kind of mythical luminosity, that, with the period styling of the film, makes it distinctly other-worldly.”

Wheatley was pleased when he saw the film and sent Terence Fisher a telegram: “Saw film yesterday. Heartiest congratulations, grateful thanks for splendid direction.”

Christopher Lee entered thoroughly into the character of the Duke. Just as he says in the film (after they find a magical grimoire, The Clavicle of Solomon, in a cupboard) “It is vital that I should go to the British Museum and examine certain occult volumes that are kept under constant lock and key”, so in real life Lee claimed to have gone to the British Museum Library and found the supposedly real lines of the Susamma ritual, to be added to the script at the end. “It’s a ritual against the forces of darkness”, he told an interviewer; “it really exists.”

Lee also came up with the “even today … in major cities”-style lines familiar from Wheatley blurbs. “Satanism is rampant in London today”, he said. “It’s generally acknowledged in certain circles that the so-called swinging city is a hotbed of Devil worship and such practices – just ask the police …”

And he was right, up to a point: it was more rampant than it had been, although this may not have been saying much. Somehow, a book that had begun life as a Thirties Appeasement novel had bounced back and hit the zeitgeist once again.

*

Simultaneously with The Devil Rides Out, Hammer were also filming The Lost Continent, an amiably awful adaptation of Wheatley’s Uncharted Seas, and when Dennis and Joan visited Hammer they looked over both productions on the same day: The Devil Rides Out was just winding up six weeks of interior shooting, before two weeks of ritual orgy scenes to be shot on location in Hampshire. As for The Lost Continent, the ethnic aspects were happily gone, and the film relied instead on giant crabs, Dana Gillespie’s cleavage, and the occasional in-joke, like a passenger reading Wheatley’s Uncharted Seas.

“One of the great cornball pictures of the decade”, said an American review:

Assortment of typically neurotic Britons on ship destined for … where? Hokier by the reel until the splendidly frenetic climax mixing sea of lost ships, degenerate lost race, superbly constructed monster crustaceans, explosions, bosoms, and more, more!

*

Wheatley was concerned with another film around this time, far closer to his heart. A friend’s film company had come up with the innovative idea of “living portraits”, and Wheatley was making a ‘Living Portrait’ of himself: a private documentary celebration of his life to be shown to his descendants after he was gone.

Wheatley drafted his own filmscript, which began with a painting of himself at his desk. The camera then dissolves into the same scene, with Wheatley at his desk in his writing clothes. “Here’s a health to you all,” he says, raising his glass: “May you drink as much fine wine in your lives as I have. My friend Jack de Manio is going to ask me a lot of questions. I’ll do my best to answer.”

The screenplay then runs through an interview account of Wheatley’s life, entirely scripted by Wheatley. Wheatley shows us his brickwork, “the trees which give me the cherries to make my Cherry Brandy”, and Joan’s needlework (“Joan is a wonderful needle-woman. She worked all the chairs – a million and a quarter stitches”).

The magic of cinema whisks us up to Cadogan Square and then to Grove Place again (“Let’s go back there”), where Wheatley shows us over his possessions (“Shot of three big stamp albums” says the screenplay; “Open at a page showing G.B.”). “You must have made a lot of money,” says de Manio. “I have”, says Wheatley, “but I contribute up to 18/-in the £ to the Welfare State”.

Over at Hutchinson, Bob Lusty and his marketing director confirm just how successful Wheatley is: “Dennis is probably the only living author who has everything he has written still in print. We keep over a million Wheatley books available.”

Finally de Manio asks Wheatley if he is afraid of death. “Not in the least”, he says, “you see, I believe in Reincarnation.” He explains that according to the happiness we give others in this life, so we will be given happiness ourselves in the next. The clincher for Wheatley, the reason why reincarnation must be true, is that if it wasn’t (with so many people “born cripples, or brought up in poverty by criminal parents”), then things just wouldn’t be fair. Old-fashioned Englishman that he was, raised on the Chums Annual, it doesn’t seem to have occurred to him that perhaps life isn’t fair.

So death is no bad thing: it is “the greatest adventure of all”, and it means being re-united with old friends. “Here’s to it!”, says Wheatley, and they drink to death from their goblets of champagne.

*

The finished film, without Jack de Manio, differs from Wheatley’s original screenplay, but it is still a spirited performance. The beginning is distinctly ‘cinematic,’ in a period way: there is an opening shot of a red curtain with ‘Dennis Wheatley’ on it, and some very dated music; the whole effect is really quite Pearl and Dean.

We see a fine Georgian house with old wisteria, and then under the house we are shown a cellar filled with thousands of bottles of wine, some of them from the nineteenth century or earlier. There are bottles of old Chartreuse, Napoleon brandy, and Imperial Tokay. Some of the bottles are in a wire-doored cabinet, where the camera zooms in slowly and emphatically on the padlock.

Wheatley shows us some favourite possessions including the Chinese Goddess Kwan-Yin (“Queen of Heaven – isn’t she lovely?”), and gives us a view of the stars on his bedroom ceiling, in real constellations and correctly orientated. He cut them out of gold paper and stuck them on himself, he tells us, so he could lie on the bed and look at them. In the bathroom we see his fish on the walls (“I cut all these fish out of illustrated books and stuck them on myself ”).

“Incidentally”, Wheatley says at one point, “we have every form of burglar alarm. What is more, I keep a shotgun in my bedroom and I wouldn’t hesitate to use it.” It sounds oddly like a warning; an unintentionally comic touch, given that the film was primarily made for his family2.

Wheatley introduces two “friends” to the camera, Blatch and Lusty, and they assure us of his success, with a million books in stock and 25 million copies sold to date. Wheatley explains that if you put a rope between the earth and the moon, you could have a Wheatley book every fifty feet.

Finally Dennis and Joan are seen walking back in through their imposing gates, with which the film ends. Where the first screenplay ended on a toast to death, the finished film seems to close on a celebration of private property.

*

Wheatley had finished his last Gregory Sallust, The White Witch of the South Seas, and was now slogging away with his new Roger Brook. In an effort to keep up with the permissive modern world, this was entitled ‘Enter The Nymphomaniac’.

In December the Wheatleys set off on another world trip, for Rio, Buenos Aires, Santiago de Chile, Mexico City, Fiji, Tonga, Samoa, Noumea, Penang, and Delhi. On the first of March 1968 they returned home, but things were no longer going so smoothly at Grove Place.

The Wheatleys were dependent on their cook-cum-housekeeper, Mrs Betty Pigache, who lived in the servants’ quarters at Grove with her husband, Captain Georges Pigache. These were no ordinary servants: Captain Georges had once had a ‘set’ in Albany, the gentleman’s apartment complex on Piccadilly where other residents had included Graham Greene, Lord Byron, and Terence Stamp. His family had owned the Café Royal, his gourmand father Georges having married the founder’s daughter. Georges Senior paid a heavy price for his gourmandising, weighing thirty-six stone and dying suddenly at the age of 47.

Despite his extensive knowledge of cooking, Captain Georges did no work for the Wheatleys, spending much of his time in local public houses. In 1968, however, with the pair of them getting old, he decided it was time to retire to a council house, taking Betty with him. This was a blow, because the Wheatleys couldn’t find a couple they liked to replace the Pigaches. To make matters worse, their gardener was also coming up for retirement. The writing was now on the wall for Grove Place. The servant problem had done for it.

As a local celebrity and a market gardener (he had a special letterhead for this, with a picture of Grove and the words ‘FRUIT, FLOWERS, VEGETABLES & HERBS’), Wheatley was the President of the New Forest Agricultural Show in July 1968, which was to be his last summer at Lymington.

Attractions included showjumping, a dog show, beekeeping displays and competitions, the Women’s Institute, rabbits, woodmen’s competitions, clay pigeon shooting, stalls from businesses, banks and charities, horticultural and floral displays, rural industries, the New Forest Hounds, and the Band of the Coldstream Guards. The committee had felt that they couldn’t afford a band, so Wheatley offered to meet the cost himself. Locally, the show might be felt to represent a fair slice of “everything decent in life”.

Wheatley threw himself into being President with characteristic vigour and sense of duty, hosting a large luncheon party in his President’s Tent. Dennis and Joan went around on separate schedules of viewings and judgings, then came the presentation of seventy-odd prize cups, and the President’s Tea for several hundred people, until around 6.30 Joan drove them both home. Now in their seventies and in indifferent health – Joan’s was starting to go first – they must have been tired by the end of it all, if buoyed up by a sense of noblesse oblige. The Show Secretary, Air Commodore Geoffrey Le Dieu, wrote to Wheatley to say that despite bad weather, “I felt that this year … there was nevertheless a happier and more cheerful atmosphere at the Show among exhibitors, helpers and visitors alike, which extended from the President down.”

Already, before the show, the Wheatleys had decided to sell Grove Place. The flat upstairs at Cadogan Square became vacant and Wheatley (or rather ‘Dennis Wheatley Ltd.’) was able to take on the remainder of the lease and put the two flats together. It was a considerable upheaval, and Wheatley had to superintend the whole move by coming up to London twice a week throughout the autumn, moving four thousand books and three thousand bottles of wine. Wheatley also took the opportunity to sell some of his wine at Christie’s, including some seventeenth-century Imperial Tokay.

The Wheatleys auctioned their surplus effects from Grove Place in October 1968, with an auctioneer in a marquee on the lawn. The sale was well publicised, the viewing was thronged, and they took over £11,000 on their discarded items. They were less lucky with the house itself, which was a difficult size to sell in those days. It wasn’t quite large enough to be used as a school or hotel, but almost too large to live in as a private house. It was put up for auction with an estimate of £40,000 and a reserve of £30,000, but failed to sell at £28,000. A few days later Wheatley accepted an offer of £29,000.

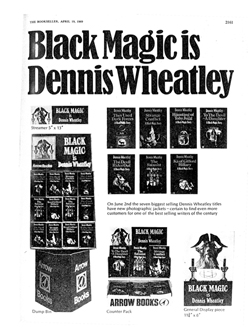

“Black Magic is Dennis Wheatley”: a trade advert from 1969.

“Now – if you dare”: the Heron Library advert, early 1970s.

Arrow paperbacks, early 1970s.

Wheatley thought that the new owner intended to live at Grove Place with his family, and hoped that it might be preserved as “a perfect example of a small Georgian Manor House.” But this was not the plan, which seems to have included leaving the doors and windows open throughout the winter to hasten the decay of the property.

Grove Place was demolished, and where a Georgian house had once stood, a housing estate in vaguely Georgian style came to replace it. Grove Place is now the name of a road, not a house, comprising twenty-odd terraced dwellings. It is certainly a more utilitarian arrangement. Some of Wheatley’s amateur brickwork still survives.

*

Hutchinson had to have a word with Wheatley about the title of ‘Enter The Nymphomaniac’, and in due course it appeared as Evil In A Mask (1969). Meanwhile The White Witch of the South Seas appeared in 1968, incorporating an expanded account of Wheatley’s voodoo ceremony into its opening. Gregory Sallust and some friends attend a macumba gathering outside Rio, in the company of a police officer, who insists the women in the party should leave their jewellery at home. They drive out in two cars, until they meet a long line of parked cars by the forest. They then go up a wooden walkway decorated with chicken heads, and so it continues until the ceremony is rained off.

Things then take a more menacing fictional turn, as the old Macumba priest stares at Gregory. His son then explains “He much opset. He believe yo’ an’ yo’ friends who come with Police enemies of him an’ make bad magic that bring rain.”

They manage to reassure the old man that this is not so, and the old man goes on to warn Gregory that a “White Witch” will come into his life, and that he must kill her when he has the chance. As for the future, the son translates further: “My father, he say yo’ have no vision to tell. Sometimes he have visions. Jus’ now, when he come in this room, he have one. He see yo’ this time tomorrow night as dead – dead in a ditch.”

*

Black people had been an all-too reliable source of menace in Wheatley’s work almost from the start, including the “bad black” servant in The Devil Rides Out, and the ethnic conflict in Uncharted Seas. In Strange Conflict, despite some intelligent and kindly black walk-on parts, Haitian Voodoo and the Third Reich were in league, and Chapter V of Curtain of Fear is appropriately entitled ‘The Persistent Negro’, featuring a razor-wielding thug. He does seem to be persistent throughout Wheatley’s writing.

The association between black people and evil runs deep in Wheatley’s work, ultimately going beyond the obvious ‘racism’ of the period, and even beyond period ideas of primitive sexuality, to a more radical conflation of ethnic blackness and visual darkness, within Wheatley’s Manichaean and Gnostic split between light and dark. Real life, meanwhile, is never as black and white as Wheatley’s fictions, but shot through with contradictions and paradoxes, and Wheatley’s favourite writer and main model, Alexander Dumas père, was black.

Roger Brook is enraged in Evil In a Mask when his wife (the incarnate “Evil” and formerly “Nymphomaniac” of the title) gives birth to a black child. His anger, says one academic commentator, “is attributable to the revealed adultery rather than to any horror of miscegenation”. Well, up to a point. But it is an explanation that might be more appropriate if it was about an event in life, not an event in a fictional narrative, where the author is responsible for all circumstances.

In fact, in the late Sixties, blackness in the ethnic sense seems to have been on Wheatley’s mind, and fears of ethnic conflict form the subject of his last great occult novel, Gateway to Hell.

1 For that reason the screenplay specifies, with reference to the Satanic chapel, “N.B. The decoration should not contain any inversion or parody of Christianity” [screenplay p.110].

2 One of Wheatley’s grandchildren quoted this scene from memory as “and if any of you watching have been looking at my nice china and nice glass, and you’re thinking of coming round to rob me, let me just say that I sleep with a loaded revolver under the pillow and I’m prepared to use it.”