Wheatley’s war ended at Christmas 1944: like a schoolboy breaking up for the last time, he was free to go on the 22nd of December.

Having been released, he began a new novel, The Man Who Missed The War. This was another of Wheatley’s ‘lost civilisation’ tales, and the public rationale for its “far from here” setting was that he was now so steeped in inside knowledge that he dared not write another contemporary spy or war story, for fear of breaking the Official Secrets Act. There may have been some truth in this, but it was also a canny way of promoting a certain image.

Based on his wartime ‘Raft Convoy’ idea, The Man Who Missed the War is the story of a man who leaves America on a raft hoping to drift into European waters. Instead he is carried to the Antarctic, where he discovers a previously unknown area with a warm climate, inhabited by a lost race who practise human sacrifice. Meanwhile he discovers that he has a stowaway on his raft, in the shape of a beautiful redhead. Together they not only survive their encounter with devil worshipping Atlanteans in cahoots with the Third Reich, but they also meet the narrator’s ghostly guardian, some pirates, some giant man-eating crabs which seem to have migrated from Uncharted Seas, and a bloodthirsty Russian aristocrat, hell-bent on becoming the ruler of a lost race of pygmies.

It was, according to Hutchinson, in “the true Wheatley tradition of adventure, rising to a terrific and truly satisfying climax”. Wheatley was Hutchinson’s prize author, and he had a good working relationship with Walter Hutchinson, so Hutchinson’s advanced him a sizeable loan1 for his new house. Grove Place was at Lymington, a notably “unspoilt” small town on the coast near Southampton. In mediaeval times it had been a major port, and its prosperity lasted until the mid-nineteenth century. Lymington had been entitled to two Members of Parliament (among them Edward Gibbon, whose Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire Wheatley owned in eight leather-bound volumes) but by Wheatley’s time it had become little more than a long, sloping High Street, the Northern side of which had once belonged to Nell Gwynne, given to her by “Old Rowley.” In a word, Wheatley found Lymington “picturesque.”

Grove Place was a Georgian house built around 1770. It had ten principal rooms, with high ceilings, tall windows and a curving main staircase. There were four acres of land and it particularly benefited from the view beyond them, sweeping over four miles of fields and woods down to the River Solent, followed by the sea and the distantly visible Isle of Wight. This vista owed a great deal to the fact that a previous owner and three other landowners had covenanted together that none of them would have any building on their land without the consent of the other three, so the view remained unbroken by suburban sprawl.

The previous owner had been an old widow, Mrs. Hall, the sister-in-law of Sir Reginald “Blinker” Hall (founder of The Economic League). Mrs. Hall had been unable to keep the place up, and the lawn and terrace were overgrown. Wheatley’s account of it in a 1946 letter shows a characteristically die-hard approach to gardening: “We moved to the country last summer and have since been fighting a furious war against dirt, decay and weeds to get the lovely old Georgian house really habitable again. It has been a great fight but we are now well on the way to victory.”

Wheatley kept a twelve bore shotgun in his bedroom, and would shoot out of the window at rooks. His daughter-in-law remembers walking towards the house when he shouted out “Stay where you are!”: a moment later Wheatley had blasted another rook, with a cry of “Death to the invaders!”

Wheatley had to do further battle with ants (‘Nippon’ ant killer, with its mushroom cloud logo, was a familiar item in the post-war British garden shed) and rabbits, for which a landed friend advised ferrets. “Leave it with me,” he wrote, “and I will do my best before you are invaded”.

A far nastier pest appeared at Grove in the form of a potential blackmailer. Wheatley spent more money on renovating and decorating than wartime economy regulations allowed, and they remained in force in this state-centred era just after the war (Earl Peel was caught spending his own money on the upkeep of his stately home and fined £25,000: about half a million pounds today). A local man discovered what Wheatley was doing and came round to see him with a proposition. He knew that Wheatley had overspent, and he offered not to inform the police if Wheatley would like to make it worth his while.

Wheatley asked for time to think, and the man agreed to come back the following morning. When the would-be extortionist returned, Wheatley’s builder (a Mr Bower) was hiding within earshot. Having invited his tormentor to put his cards on the table, Wheatley then produced Mr Bower. “You are attempting to blackmail me, and I can call Mr Bower as a witness”, he said: “One word about the decorating, and I’ll have you in the jug.” And that was the end of that.

*

Wheatley’s war had hardly been austere, but now he was keen to throw off what few privations there were. In 1946 he wrote to the firm of Maurice Meyer, drink shippers, to re-establish his supplies of Aurum and Kummel. The Aurum factory was still out of action, having been looted by the Germans for steel and copper, and ordinary pre-war Kummel was now fetching £8 to £15 a bottle (£200 to £400). Meyer’s were gratified by his request: “It is pleasing to receive your refreshing letter”, they wrote: “Asking for Hunting Kummel and Aurum seems like a breath from the past.” Meyers promised to advise him when they were again in possession of Aurum and Kummel, and meanwhile invited him to drop in for a cup of tea if nearby.

It is a pre-war Kummel – pre-First War, in this case – that Gregory Sallust and Sir Pellinore Gwaine-Cust split a bottle of in The Black Baroness. “Hurrah! The fatted calf! ” says Gregory, seeing the cobwebby bottle as he enters – where else in a Wheatley book? – the library. “What’s that?” says Sir Pellinore; “Oh, you mean the pre-1914 Mentzendorff’s Kummel … They don’t make stuff like this in Russia these days; but there it is – the whole darned world’s gone to pot in this last half-century.”

Wheatley’s luxurious tastes were quite widely known. A letter arrived at Grove Place in 1946 to introduce a budding actor, formerly in the RAF, by the name of Christopher Lee. Lee is a great friend of the letter writer, and the two of them have just been drinking port and talking about Wheatley, of whom Lee is an “enormous admirer”: “Although he has never met you he knows your life history and your love of the good things of life.”

Wheatley was now “established” at Grove Place in a more gentlemanly style than he had ever really enjoyed before: these were to be some of the best years of his life, if relatively uneventful. The thrills and spills were largely over. Wheatley’s main activity in the post-war years was writing.

Wheatley was not a believer in waiting for inspiration, and found it would come to order if he first forced himself to write. He tried various methods of getting his narrative down, including dictation, but he never mastered the writerly trance in the manner of Joan Grant or Barbara Cartland, and found dictation went too fast to develop situations. Instead he found the best method for him to think and write was to use a soft pencil, with an eraser handy, giving an ease of composition that he didn’t get with a pen. He averaged about four sheets of foolscap a day and at that speed he could finish a book in seven months, since – being anxious to give his reader-customers good value – his books were around twice the length of the normal thriller, averaging 160,000 words.

Wheatley worked with self-discipline and absolute seriousness (“You couldn’t go and stay while he was working”), beginning at about nine in the morning. He would spend an hour or two with his secretary, dealing with the post from his public, then at around ten thirty or eleven he would press on with the current book. At one he would have a simple lunch, followed by another hour or so of work until around half two, and then he would go to sleep to pre-empt the afternoon slump (like Churchill, he believed “work in the afternoon has almost invariably to be done again”). He would sleep on his sofa until four, when a cup of tea was brought to him, and he roused himself to write until dinner. After dinner he would go back to work until midnight or, if it was going well, until two o’clock in the morning.

Wheatley worked solidly like this for seven or eight months of the year, including Saturdays, during which time he was effectively “in purdah”, as a friend put it. He also travelled abroad with Joan for two or three months, which doubled as research for settings and local colour.

One of the great pleasures of Grove Place for the Wheatleys turned out to be the proximity of Constance, Duchess of Westminster (“Sheila” to friends), who became a great friend to both of them. She was a strong woman of the sort Wheatley admired, and he was particularly impressed by an adventure she had in Istanbul before the First War. She heard that a great ceremony was to be held at Ramadan inside the Hagia Sophia mosque – then far from being the tourist destination it has since become – but she was warned that it was impossible for her to see it, since women were forbidden. Ordering one of her sailors to hand over his clothes, she infiltrated her way into the ceremony, alone and disguised as a man, despite the fact that (as Wheatley understood it) “if discovered she would be torn to pieces”.

The less attractive side of this forceful character was that she could be arrogant, and would often speak to her second husband “Fitz” – Wing Commander James Fitzpatrick Lewis – as if he was a servant. But Wheatley was spellbound by her stories of life in the great Edwardian houses, and he must have found pleasure in the fact that she was the former wife of Hugh Grosvenor, Second Duke of Westminster, who had made such an impression on Wheatley when Wheatley was his wine merchant: he figured as “His Grace the Duke of Blank” in At The Sign of the Flagon of Gold, and he was the owner of Eaton Hall. Wheatley would not have been Wheatley if he hadn’t been at least a little gratified by the fact that he was now a good friend of His Grace’s former wife.

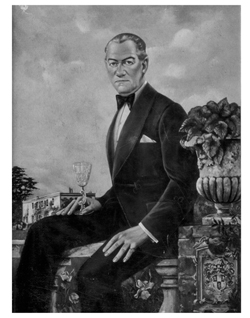

Wheatley at Grove Place, painted by Cynthia Montefiore.

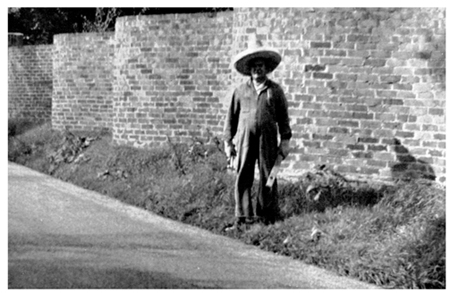

Wheatley the amateur bricklayer, with some of his handiwork.

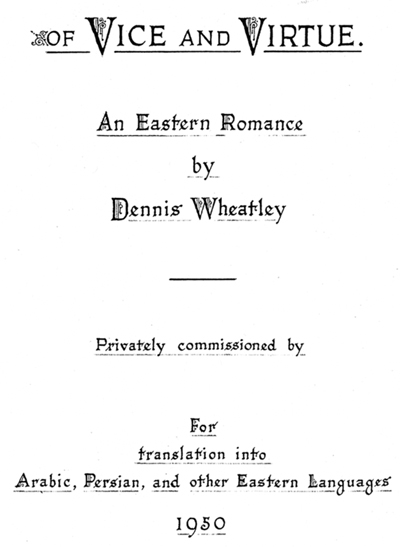

Commissioned by? Wheatley’s own copy of his Islamic propaganda novelOf Vice and Virtue.

*

Largely as a result of contacts made during the War, Wheatley’s post-war circle was now more aristocratic and military than it had been. It is probably fair to say that Wheatley took a certain pride in knowing members of the aristocracy, and that he was never quite unconscious of their rank.

When Wheatley wasn’t working he was often entertaining. “I thought I ought to let you know that by approx 11 o’clock this morning we had both nearly recovered from your most wonderful luncheon of yesterday. It truly was the most enjoyable time we have spent for ages and Helen and I thank you both a thousand times … Paradise we are told exists in another world, but I am beginning to suspect that such a story is but a cover plan put about by the nonconformists and their like and by the Cripps2 and other killjoys that inhabit this island of ours.” The same man, an impecunious earl, writes on another occasion, “Thank you a thousand times for your hospitality and may God bless you for the hock – that delectable hock.”

Another friend, a colonel, writes “What with you, Moet and Chandon and that hat – not to mention the bricks – what more could one want??”. The hat might well be the extraordinary straw number that Wheatley is wearing in the photograph on the back of The White Witch of the South Seas3. More about bricks later, although another friend writes “I would like to thank you for a most enjoyable weekend, even though I think I laid some of my bricks slightly, only slightly, out of the perpendicular.” The wife of the Hereditary Falconer of England (the 13th Duke of St Albans, formerly in Military Intelligence and Psychological Warfare) writes to thank Joan for a delightful evening with the Richmonds (i.e. Freddy, Duke of Richmond, and his wife Betty) and says how much she enjoyed seeing Joan’s needlework.

And so the thank-you letters go on: “just a line to thank you …”; “A really lovely evening …”; “Thank you both ever so much for a most delightful visit which we enjoyed greatly – I much enjoyed meeting “the 18B man” [i.e. a man interned as a Fascist during the war under Regulation 18B] who I thought was very amusing and entertaining but probably one doesn’t want to see him too often …” Even allowing for the high level of politeness among Wheatley’s friends (“How kind of you to invite me and how base you must think me not to have replied before”) it is clear that a good time was had by all – “P.S. the lunch was terrific!”

*

Wheatley’s next book, Codeword: Golden Fleece, published in May 1946, is another instance of his responsive relationship to his readers. It arose from a throwaway line in the first chapter of Strange Conflict, when the Duke de Richleau mentions to Sir Pellinore Gwaine-Cust that the four of them were in Poland at the start of the War. Readers wrote to Wheatley, asking what had happened and what they had missed, and so Codeword: Golden Fleece was written to fill in the story. As Francois Truchaud has written, “It is a beautiful example of the autonomous life of novelistic characters obliging their Creator to tell their adventures”.

Whatever misgivings Wheatley might have had about the Official Secrets Act, Codeword: Golden Fleece was a World War Two story involving economic sabotage of Germany’s oil supplies. The 1963 Arrow blurb added “It can now be revealed” that the plot was based on facts given to Wheatley, as a member of the JPS, by a Foreign Office colleague: a French nobleman had succeed in acquiring a controlling interest in the Danube oil barges, and getting them into Turkish waters, depriving the German air force of fuel. Six months later Wheatley followed this with another Gregory Sallust, Come Into My Parlour, then shelved Sallust’s wartime adventures for another twelve years. A new hero was about to be born.

1 £5,000, or about £150,000 by today’s standards: property was relatively cheaper then.

2 I.e. the Rt.Hon Sir Stafford Cripps, (1889–1952), Labour politician.

3 The bookseller’s note in my copy says “one of the most extraordinary author portraits I’ve ever seen”, while the photo caption reads “Here we see the author about to go for a swim from a palm-fringed island in one of the lovely blue lagoons of the South Seas.” With its brickwork and yew it looks more like the garden at Grove.