Of all the “top boys” that Wheatley befriended through his research, none was more important than Montague Summers, who has been described as “a mysterious figure, with his large moon-like face, wearing a black shovel hat and flowing cape, flitting bat-like across the literary scene of the twenties and early thirties …”.

With his silvery locks and his outdated clerical garb, Wheatley thought he looked like a Restoration bishop. Summers’s extravagantly ecclesiastical outfits were notorious, and one witness remembers him in a purple stock, black cassock, wide black silk cincture with a foot-deep purple fringe, and large silver buckles on his patent-leather shoes.

And this was despite the fact that there were doubts about whether he was really ordained as a priest: he was frowned on by the ecclesiastical authorities. When he lived in Hove he acted as private chaplain to the Hon. Mrs. Ermyntrude Greville-Nugent, who had a private oratory in her house where Summers would officiate, until the Bishop of Southwark put a firm stop to it.

Wheatley used Summers as the model for Canon Copely-Syle in To The Devil – A Daughter, but it could further be argued that it was Summers who stood behind Wheatley’s entire occult output, with his view of Satanism as a criminal conspiracy posing an enduring menace to society. For Summers, witchcraft and Satanism were real; they were “still” practised (something of a paradox, because they are largely modern inventions) and they were all around us. More than that, they had a political aspect.

Summers’s 1926 History of Witchcraft and Demonology set the subject back four hundred years. It was an ultra-orthodox fire-and-brimstone compendium of witch hunting lore, and its credulous details of Sabbaths, Black Masses, and infant sacrifices would provide the raw material for numerous other books on the subject.

Wheatley prided himself on his research. This plays a special role in his occult books, where the accumulation of quasi-factual information suspends disbelief and enfolds the reader in the books’ distinctive atmosphere. This effect is already a feature of Summers work, where mountainous quantities of scholarship tend to overwhelm scepticism and draw the reader in.

Summers recounts a story from 1895, when the agents of Prince Borghese regained possession of a flat in the Palazzo Borghese from an uncooperative tenant. Having gained entry, they discovered why he wanted to be left undisturbed.

The walls were hung all round from ceiling to floor with heavy curtains of silk damask, scarlet and black, excluding the light; at the further end there stretched a large tapestry upon which was woven in more than life-size a figure of Lucifer, colossal, triumphant, dominating the whole. Exactly beneath an altar had been built, amply furnished for the liturgy of hell: candles, vessels, rituals, missals, nothing was lacking. Cushioned prie-dieus and luxurious chairs, crimson and gold, were set in order for the assistants; the chamber being lit by electricity, fantastically arrayed so as to glare from an enormous human eye.

Compare the passage in The Devil Rides Out where the Duc de Richleau is explaining the reality of modern Satanism to Rex Van Ryn:

‘… Borghese’s agents forced an entry. What do you think they found?’ ‘Lord knows.’ Rex shook his head.

The principal salon had been redecorated (“at enormous cost”, a very Wheatley touch) and converted into a Satanic Temple:

‘The walls were hung from ceiling to floor with heavy curtains of silk damask, scarlet and black to exclude the light; at the farther end there stretched a large tapestry upon which was woven a colossal figure of Lucifer dominating the whole. Beneath, an altar had been built and amply furnished with the whole liturgy of Hell; black candles, vessels, rituals, nothing was lacking. Cushioned prie-dieus and luxurious chairs, crimson and gold, were set in order for the assistants, and the chamber lit with electricity fantastically arranged so that it should glare through an enormous human eye.’

De Richleau hammered the desk with his clenched fist. ‘These are facts I’m giving you Rex – facts, d’you hear, things I can prove by eye-witnesses still living.’

Summers’s story is not factual. It was concocted by the nineteenth-century hoaxer Leo Taxil in order to smear the tenant of the flat, an Italian politician named Adriano Lemmi.

Recent examples were another Summers speciality. The Duke de Richleau asks Rex when he thinks the last trial for witchcraft took place. “I’ll say it was all of a hundred and fifty years ago”, replies Rex, to which the Duke pulls out his trump card: “No, it was in January, 1926, at Melun near Paris.” It was the Madame Mesmin case, a bizarre story from Chapter V of Summers’s 1927 book The Geography of Witchcraft.

The sheer matter-of-factness of Summers’s belief is coercive, along with an intellectual snobbery that is completely in conflict with modern thinking, but so confident that it seems to have not only the moral but even the intellectual high ground. Summers regarded his opponents as “vulgarians,” and he liked to quote the reply of a priest (or in his phrase a “Prince of the Church”) to the woman who told him she was a freethinker: “Free, Madam, I doubt not, but a thinker, no.”

*

“The cult of the Devil”, says Summers, “is the most terrible power at work in the world today.” As in Wheatley, his belief in the absolute conflict between good and evil is allied to cultural pessimism, with “monstrous things below the surface of our cracking civilisation”. Witches are the continuation of heretics, who were in the business of “revolution and red anarchy”; they were “red hot anarchists” who fully deserved to be burnt at the stake, while “The Black International” of Satanism has always been in the business of fomenting revolutions, including the French and Russian.

More significant than the alleged politics of a largely fictional group, however, is the fact that Summers found occultism such a satisfyingly arcane field for his obsessional and reactionary scholarship. Like his dress, it was part of the anomie he felt in the modern world:

Above all, I hate the sceptic and modernist in religion, the Atheist, the Agnostic, the Communist, and all Socialism in whatever guise or masquerade.

Summers explained the issues when he talked about witchcraft with Lord Balfour, a former Conservative Prime Minister. Balfour was an intellectual who had published several books on philosophy and theology, and he questioned Summers on the “ultimate aim and object” of witches. As Summers tells it, Balfour “found it hard to believe from a metaphysical point of view that there could be people who craved evil for evil’s sake. His intellect was, I think, too noble and too lofty to conceive of such degradations and culpability, unless we had explained the problem by sheer lunacy.” But lunacy was not a sufficient explanation of the problem as Summers conceived it, so he “ventured to stray into the political arena”:

“Well, Lord Balfour,” I answered, “you have only to think of the political views of some of your opponents.” And I cited certain persons whose ideas appeared to be fundamentally anarchical and to end logically in absolute nihilism. “That is the witch philosophy,” I said.

H.G.Wells made a perceptive point about Summers’s world view in his 1927 article, ‘Communism and Witchcraft’. After reading Summers’s History of Witchcraft and Demonology alongside various utterances about Russian Bolshevism, “I find a curious confusion in my mind between the two.” Wells quotes Summers’s condemnation of the witch as “an evil liver; a social pest and parasite; the devotee of a loathly and obscene creed; an adept at poisoning, blackmail, and all creeping crimes …” (and so on) and then observes that any reader of the British newspapers of the time might be unsure whether this passage is describing Gilles De Rais, Lunacharsky, Old Mother Shipton, or Lenin.

Wells’s tolerant view of Bolshevism has dated, but his wider argument is still of interest. He cites the “interesting views” of “that great historical writer, Mrs.Nesta Webster” – he is being ironic, since she is better remembered as a conspiracy theorist and anti-Semite – on the fact that “modern Communism is the lineal descendant of the black traditions of mediaeval sorcery, Manichaean heresies, Free Masonry, and the Witch of Endor.”

This is exactly what Wheatley claims in The Haunting of Toby Jugg and elsewhere. Perhaps, says Wells, “mankind has a standing need for somebody to tar, feather and burn. Perhaps if there was no devil, men would have to invent one.”

*

Things were not so black and white in Summers’s own life. He has been described as “one of the most enigmatical figures of the century,” and most people found him to be a delightful old gentleman. His Who’s Who entry, which lists among his recreations “talking to intelligent dogs, that is, all dogs,” makes him seem rather engaging. He was also a devotee of that great Victorian pastime, the toy theatre (or as he preferred to call it, “the miniature stage”) and he liked nothing better than to read a good book, cosily “chair-croodled” – his English was highly idiosyncratic – beside a blazing fire.

At the same time, some people found him indefinably repellent and sinister, like a “split personality” or “a man wearing a mask”, and perhaps they were right. It turns out that Summers was a Satanist himself.

The person who has gone most convincingly into the mystery of Montague Summers is Timothy d’Arch Smith, who first presented his findings in a talk given to The Society (“The Society is a society in London”, he explains in a footnote; “In accordance with occult precepts it requires no further advertisement.”)

As a young man Summers had been steeped in the atmosphere of the 1890s and the work of Oscar Wilde, and he was in the habit of saying “Tell me strange things”, a request with a very Nineties feel to it. His first published work had been a 1907 volume of poems entitled Antinous, condemned by one reviewer as “the nadir of corruption” and containing poems such as ‘To A Dead Acolyte,’ in which some sort of ceremony seems to be in progress – Summers was always of a ritualistic bent – watched over by an ancient figure:

…

Across the crowded palace

His bright eyes gleam with malice,

When we uplift the chalice,

Brimful of sanguine wine.

No mass more sweet than this is,

A liturgy of kisses,

What time the metheglin hisses

Plashed o’er the fumid shrine.

He dreams of bygone pleasures,

Whose passion kenned no measures,

Of all his secret treasures,

The lust of long dead men.

And thro’ dishevelled tresses,

He smiles at our caresses,

As great power now as then.

Metheglin, evil as it might sound, is just a type of mead, but the “He” in question is the Old One himself. “This is Satanism”, says d’Arch Smith, “Satanism celebrated by Montague Summers in 1907 with as much fervour as in 1926 he would denounce it in his History of Witchcraft and Demonology.”

A man calling himself Anatole James had met Summers in 1918, and they found they had things in common. In consequence, on Boxing Day, 1918, Summers had asked James to his house in Eton Road, Hampstead, to take part in a Black Mass. Satanism being a recent invention, a recent academic book accords this Boxing Day performance the unexpected status of “the earliest Black Mass for which there is reliable evidence”. Unaware that he was at a historic event, and not being sufficiently religious to find it either shocking or exciting, James was merely bored, but he understood well enough that what was going on was a perversion of the Catholic rite.

James was not invited to the Black Mass again, but he continued to see Summers socially: heavily made up and perfumed, drunk on liqueurs, Summers would cruise the London streets in search of young men. One day Summers confided his particular taste: “He was aroused only by devout young Catholics, their subsequent corruption giving him inexhaustible pleasure.”

And so Summers might have continued, but something seems to have happened. Around 1923 he cut James dead in the street and embarked on his fevered and credulous series of inquisitorial, rack and hellfire invectives against witchcraft, Satanism, demonolatry, diabolism, and black magic. Was there an element of hypocrisy in this later career, as has been suggested, or even showmanship? D’Arch Smith thinks not, intuiting instead that Summers received a violent spiritual shock, and learned a lesson which he phrases in terms more Manichaean than anything in Christian theology:

he had discovered (and not a moment too soon) that the god he worshipped and the god who warred against that god were professionals.

*

Wheatley was aware that there were sinister rumours about Summers, and that his ordination as a priest had been questioned, but they should still have got on well. Wheatley was charming, respectful, and eager to learn, and both men were keen bibliophiles, reactionary in their politics, and fond of liqueurs.

Wheatley was a receptive ear for Summers’s stories, like his experience of carrying out an exorcism in Ireland. A peasant woman was possessed by a demon, and when Summers arrived at the cottage she was foaming at the mouth and had to be physically restrained. Summers performed the ceremony of exorcism, with ‘bell, book and candle’, and then – so he apparently told Wheatley – a small black cloud came out of the woman’s mouth. She became quiet, and the black cloud disappeared into a leg of cold mutton that was sitting on the table for supper. A few moments later, it was swarming with maggots.

In fact this anecdote – which Wheatley re-tells several times – appears to be taken from a short tale by R.H.Benson, ‘Father Meuron’s Tale’, in a book of Benson’s stories entitled A Mirror of Shalott. Benson’s short fictions had also appeared in The Ecclesiastical Review and The Catholic Fireside, both of which one can imagine Summers curling up with.

After dining with Dennis and Joan, Summers invited them to stay for the weekend. He was living at Wykeham House at Alresford in Hampshire where, as at his other residences, he set up his own private oratory. It is likely that Summers’s interiors were something of a moveable feast, so a visitor’s description of the decor in another Summers house – this one at Richmond, where he also had a statue of Pan as the “garden god” – may approximate to the ambience Wheatley would have encountered. The house was rather gloomy, and this gloom was heightened by old-fashioned furnishings and a large number of Italianate and ‘Gothick’ oil paintings. The oratory was in an upper room, and at one end was a large altar, with gilt candlesticks and damask hangings, surmounted by a heavily framed oil painting of a saint. “It has been said”, continues the visitor, “that the house was sinister. It never struck me as such, but exactly the kind one would expect as the home of a man possessing the tastes of Summers.” He was received in the library by Summers, with his soutane and “twinkling eyes”. Twinkling eyes were not to be the aspect of Summers that he revealed to Wheatley.

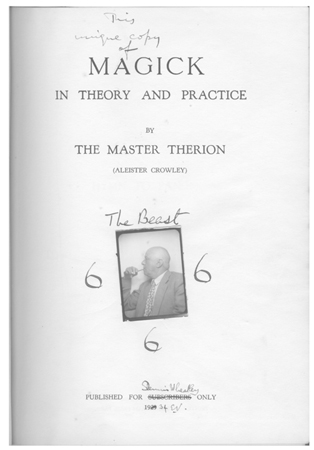

Wheatley’s customised copy of Magick, from Aleister Crowley.

The Reverend: former Satanist and dubious clergyman Montague Summers.

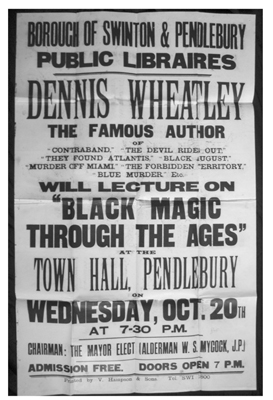

On the road: one of Wheatley’s Thirties lectures on Black Magic.

Wheatley and Joan “motored down” to Alresford on the Friday afternoon, and while they were being shown around the garden, Joan saw an enormous toad. “He is the reincarnation of a dear friend,” explained Summers benignly; “I’m just looking after him.”

The room that Summers had given the Wheatleys to sleep in seemed to be full of large spiders. Feeling Summers must have known this, and that it was at the very least inhospitable – almost a malevolent practical joke – Wheatley had no hesitation in whacking them with a shoe. When Wheatley complained, Summers simply said “I like spiders”.

After dinner (or possibly the following morning: Wheatley’s accounts vary) Summers showed Wheatley into a small room with a large pile of books lying on the floor. Picking up a leather bound book, Summers assured Wheatley it was very rare (he could have described it as being “of the last rarity”, a phrase of which he was fond) and that it was just the thing Wheatley needed. Not only that, but – although it was worth far more – he could let Wheatley have it for a mere fifty pounds.

Wheatley didn’t recognise the title, didn’t feel he could afford it, and didn’t want it. As politely as possible, he said he no longer collected that type of book. A moment later, he had never seen such an expression come over a human face. Summers’ mask slipped, and from benevolent calm he suddenly became “positively demoniac” with fury, throwing the book at the floor.

Goodwill had broken down, and the Wheatleys were anxious to escape. There was a well-known wheeze of the time for escaping from dull country house parties, and this is what they used. (A 1933 manual of etiquette gives the drill: “You must be careful not to telephone or telegraph from the house and, in every other way, to cover up your tracks … evolve some telegraph code for your family. You wire “How is Fido?” and promptly receive a message: “Grandma dying come home immediately.”)

Wheatley left Summers’s house on Sunday morning for the Post Office, where he sent a telegram to the nanny, asking her to send a wire saying young Colin was ill. It arrived at Alresford shortly after lunch, allowing them to pack hastily and leave. They motored home, and Wheatley never saw Summers (“the perhaps not so Reverend gentleman”) again.

*

At any rate, that is the account that Wheatley gives in his autobiography and elsewhere, but Summers’s surviving letters to him tell a different story. Although Wheatley had drawn heavily on Summers’s work for The Devil Rides Out he didn’t make contact with him until after it was published, when they struck up a warm correspondence.

Summers enjoyed The Devil Rides Out immensely: he found it so unputdownable he had to delay work on correcting the proofs of his own book The Playhouse of Pepys until he had finished it. He was particularly impressed by Wheatley’s power of narrative and by the way he blended fact and fiction (“one stops now and again to ask oneself where the first ends and the latter begins, which is a very subtle achievement”).

Some of this so-called fact was from Summers himself, of course; he commended Wheatley on the accuracy of his description of Prince Borghese’s Satanic temple, although he had to tell him it was in Rome and not Venice. “I actually saw the Templum Palladium,” he added, “and naturally at the time the thing caused a resounding scandal.”

Summers visited the Wheatleys in London in July 1935, when he talked and talked and talked; Joan may have found it a strain. They nevertheless went down to stay with Summers and his partner, Hector Stuart-Forbes, at Wykeham House, Alresford, for the weekend bridging August-September, and they seem not to have fallen out too badly because correspondence continues cordially (although Wheatley told him how busy he was, as he had with Crowley) into the Autumn, by which time Summers had moved to Brighton. They met again in London, and at Christmas 1935 Summers seems to have given him an inscribed copy of his book The Werewolf.

Wheatley’s story about the rare book may be inspired by Summers trying to borrow five pounds – more than it sounds, in 19351 – in October, and offering him the Gothic novel Varney the Vampire (“a rarity of the first order”) as security on the loan, telling him it was worth a hundred pounds. Wheatley evidently checked and found it was worth no such sum, leading to Summers’s wonderfully diplomatic but unmistakably ‘caught out’ reply “It is very good of you to have made enquiries about Varney the Vampire. … How prices have dropped !”

*

Wheatley’s relationship with Summers cooled, and he may not have liked Crowley very much in the first place, but he always remembered Rollo Ahmed with affection. Ahmed was a magical acquaintance of Crowley, whose diary records a demonstration announced by Ahmed in which he was to drink a bottle of whisky and remain completely sober, due to his mastery of the mystic arts. The appointed time came and there was “one absentee: Rollo.”

Ahmed was to all intents and purposes West Indian, but he claimed to be from Egypt, which increased Wheatley’s respect for him. He had apparently travelled extensively in the jungles of South America and in Asia, and it was in Burma that he had taken up yoga, at which he was now an expert.

After the great success of The Devil Rides Out a publisher asked Wheatley to write a non-fiction book on magic, which he felt unqualified to do. Instead he recommended Ahmed, who wrote The Black Art. Originally to have been entitled The Left Hand path: A Study of Black Magic, this was a global condemnation in the Summers tradition but with more attention to anthropology and the horrible doings of “primitive peoples.” He dedicated it to Wheatley, who wrote a warm introduction, and he followed it with a novel, I Rise: The Life Story of a Negro.

Wheatley had three stories about Ahmed. On one occasion he had Ahmed round with a man from the Society for Psychic Research, and the man asked Wheatley if he had seen the little black imp hopping about behind Ahmed. Wheatley hadn’t, and it did cross his mind that the man might be pulling his leg. Later he heard that Ahmed had bungled a ritual and failed to master a demon, who made all his teeth fall out. On a happier note, Wheatley was very impressed that when they had Ahmed round to Queen’s Gate one cold evening, Ahmed had come all the way from Clapham without an overcoat and yet his hands were “warm as toast”.

This was apparently due to his mastery of yoga, and he drew up a course in it for Dennis and Joan to follow. Most of it was about health and correct breathing, and Wheatley was keen to get on to more advanced areas, notably awakening the Kundalini power, but Ahmed replied “I think that the Kundalini or spinal concentration is just a bit dangerous for you at the present, as you have not yet established the Breathing. I am anxious to give you the best, but feel that we must make haste slowly.”

Instead, Ahmed substituted “Transmutation of the Reproductive Energy for Brain Stimulation”; “The energy thus transmuted may be turned into new channels and used to great advantage.”

Wheatley failed to stick at his yoga. Ahmed was meanwhile having trouble with what he called “the demon finance” – already known to Tombe and Wheatley as “the Boodle Fiend” – and making a precarious living by giving public lectures on the South Coast, such as ‘The Magic of the Mind’ by The International Lecturer and Psychologist Rollo Ahmed: “Extraordinary demonstrations, and a brilliant demonstration by the only coloured author in Europe”. There would be a silver collection afterwards (a half crown, two and sixpence, was about five pounds today) and the further offer of instruction in Yoga, “adapted for Western vibrations”.

Ahmed lived in a fourth floor flat at 23 Old Stein, Brighton, but with Wheatley’s help as a referee he was trying to rent a house or bungalow in the Worthing or Hove area, particularly for the benefit of his sick wife, and he eventually found one in Shoreham. Unknown to Wheatley, Ahmed had already served two prison sentences for fraud, and was to go down for a longer one in 1946. Wheatley found him some work with MI5 at the beginning of the war, but afterwards they lost touch.

There may have been an element of showmanship in Ahmed, but Wheatley liked him. He remembered him not only as the most interesting of the occultists he met, but as “a jolly fellow”, and that always mattered to Wheatley.

*

Another top chap in the field who had an element of showmanship was Harry Price, psychical researcher and “ghost hunter”; this would have reminded Wheatley of Carnacki the Ghost-Finder. Price was a skilled amateur conjuror who pioneered the scientific investigation of psychic phenomena and exposed a number of fraudulent mediums, although suspicions of fraud subsequently arose around Price himself. He seems to have ruthlessly exposed nine-tenths of supposedly supernatural events but then become excessively enthusiastic about the remainder, with an element of gullibility or worse. “They don’t want the debunk,” he once said of the public, “they want the bunk, and that is what we’ll give them.”

Price had recently been involved in what can only be described as a publicity stunt, when with the collaboration of the once famous Professor Joad, later to come unstuck through travelling without a railway ticket, he staged the performance of a mediaeval ritual in Germany. This involved a virgin girl and a goat, which was supposed to metamorphose into a handsome young man. The goat remained unchanged, surprising nobody, and Price claimed that this exposed the fatuity of Black Magic in the modern world.

A year earlier he had told a journalist that there were many Satanists in England.

The devotees are a degraded type, and they find secrecy one of the allurements of the cult … I am of the opinion, however, that the headquarters are not here. I know there is one in Lyons, and also there are many followers in Paris … I have attended a Black Mass in Paris. It was both spectacular and startling, but most of the performances are reserved for the initiates. They are to be guessed at rather than described.

Price had a private income, accumulated a library of around 20,000 books, and was a member of the Reform Club. Wheatley and Joan could have him to dinner at Queen’s Gate without fearing he would behave badly, unlike Crowley. He was very English in manner (like Wheatley himself, “Price was as totally English as a man can be,” remembered a friend, “a person impossible to think of as other than English”) and he radiated boyish enthusiasm, which would no doubt have rubbed off on Wheatley.

Price’s finest hour came in the investigation of Borley Rectory, supposedly “the world’s best authenticated haunted house”. Price went there with a suitcase full of recording gadgets and a hamper from Fortnum and Mason, although Fortnums were not to blame when a bottle of Gevry Chambertin turned into black ink. Price wrote no less than three books about the complicated web of events at Borley, which included a possible murder, a coach, a nun, and some poltergeist scribblings.

Witnesses included a servant girl, a clergyman and his family, and a second clergyman and his wife: the Reverend and Mrs Foyster. It now seems Marianne Foyster played the lead role in faking phenomena, but Borley was the site of multiple frauds and collusions. Colluding parties may have included Price himself, who had stumbled into a network of what one commentator calls “cruel tricks played upon one another by the members of a household which lived in an atmosphere of obsessive love, sexual jealousy and suspicion.”

When it comes to fraud, however, a desperate former army officer, one Captain Gregson, trumped the lot of them in 1939. He torched the place and burnt it to the ground for the insurance money, in a Welcomes-style fire.

*

Wheatley had mixed feelings about occultists, and in some ways he found them rather wretched. For one thing, they never seemed to have any money: they were always trying to cadge or sell him something. “No saying is less true than that ‘the Devil looks after his own’ ” he wrote; “I have never yet met anyone who practised Black, or even Grey, Magic who was not hard up.”

Now he was ready to write his masterpiece, the book that would virtually invent hardcore occultism – or its popular image – for the twentieth century. It was “a new adventure featuring the four friends from The Forbidden Territory,” originally entitled Black Magic and Talisman of Evil; but it is better known to us under its published title, The Devil Rides Out.

1 At today’s values about £250 by purchasing power or £1000 by earnings, which were relatively lower then.