Things were looking ominous in the Thirties. Unemployment reached two and a half million in 1931, and abroad, in addition to the spectre of Bolshevism, there were rising dictators and the possibility of war. To Auden it was a “low dishonest decade,” while for Sunday Dispatch editor Collin Brooks – an associate of both Crowley and the press baron Lord Rothermere – it was nothing less than “the devil’s decade”.

Hitler had come to power in 1933, and paganism had become official in Germany. Third Reich historian Michael Burleigh has argued that Nazism itself is best understood as a political religion. The economist John Maynard Keynes made a similar point about Russia: “If Communism achieves a certain success, it will achieve it not as an improved economic technique but as a religion.” Irrational forces were now abroad. Wittgenstein caught this atavistic return to a pre-Enlightenment world when he said of the Nazis: “Just think what it must mean, when the government of a country is taken over by a set of gangsters. The dark ages are coming again. I wouldn’t be surprised … to see such horrors as people being burnt alive as witches.”

People expected a new war to be like the last, but worse. There would be Somme-like attrition, but there would also be new weapons such as “death rays”, and the poison-gas bombing of cities. The technology of aerial war and bombing was known to have improved, and it was widely believed London would be completely destroyed in the opening hours of a new conflict. “We thought that the war would be as depicted in H.G.Wells’s film, Things to Come,” remembered writer Robert Aickman, “involving almost universal and nearly instantaneous obliteration.”

When Alfred Hitchcock contacted Wheatley and asked him to write a screenplay about the bombing of London, Wheatley remembered “the terror depicted on his normally cherubic countenance” and the vividness of the scenario: “as he talked to me about it I could almost hear the bombs bursting.”

*

Conservative and Establishment opinion saw Hitler as the lesser of two evils, and even as a useful bulwark against Bolshevism. Respectable figures like Lloyd George could admire what Hitler was doing for Germany – he wrote an enthusiastic piece about it in the Daily Express in 1936 – and as late as 1937 Lord Halifax, the Deputy Prime Minister, could say to Hitler “on behalf of the British Government I congratulate you on crushing communism in Germany and standing as a bulwark against Russia.” Wheatley was very much of this persuasion.

The anti-war faction covered a whole spectrum from pacifists to fascists. Prominent advocates of peace included the novelist Sir Philip Gibbs; press barons Lord Rothermere, Lord Northcliffe and Lord Beaverbrook; the Aga Khan; conservative politician R.A. ‘Rab’ Butler; Lord Londonderry; the Duke of Westminster; Montagu Norman, the governor of the Bank of England; and many others. The Times newspaper was also notably in favour of Appeasement.

Wheatley particularly admired Sir Philip Gibbs, whose loathing of war came from being a war correspondent in the First, and in the Thirties he wrote several anti-war novels. Another honourable example was Lord Beaverbrook, for whom Appeasement was a less craven policy than the word suggests. Beaverbrook’s emphasis was on Isolation: he believed Britain should keep out of Europe and stay close to her Empire, while re-arming. He had helped prevent Britain going to war with Turkey in 1922, and liked to quote Bonar Law: “We cannot act alone as the policemen of the world.”

Historian A.J.P.Taylor commented in his biography of Beaverbrook that if the British people had been told “the price of overthrowing Hitler would be twenty-five million dead, they might have hesitated … they might even have hesitated … if they had been told that that the price of destroying Germany would be Soviet domination of Eastern Europe.”

“Do not be led into a warlike course by our hatred of dictators,” Beaverbrook wrote in the Express, “Let the people who are misgoverned free themselves of their autocrats.” In 1934, a few months before The Devil Rides Out, the Express produced a book of war photographs with a skull on the cover entitled Covenants with Death: “The purpose of this book is to reveal the horror, suffering and essential bestiality of modern war.”

One consequence of the Express’s anti-war line was that Tom Driberg, in his Hickey column, regularly assured the public there would be no war (as late as 1939 “Hickey” was writing “My tip: no war this crisis.”). When he collected his Hickey columns for book publication he quietly suppressed his anti-war statements and said he always knew that war was inevitable.

Driberg and Wheatley both exaggerate how early they were prepared for war in their later recollections, along the lines observed by Rupert Croft-Cooke in his comments on Munich. When Chamberlain proclaimed “Peace in our time”, “The rapturous crowds at the airport who cheered him hysterically as he waved that ridiculous piece of paper were not exceptional people – they cheered for all but a tiny minority of not necessarily wiser Britons.” To which he adds the very apposite footnote, “Though in that tiny minority, I have since been interested to note, were almost all the autobiographers of the future …”

*

Beaverbrook, meanwhile, was producing rhetoric that wouldn’t be out of place in The Devil Rides Out: “The powers of darkness are gathering,” he wrote in July 1934, reminding readers that interference in Europe would mean war. Later the same month, he added “The British Empire meddling in the concerns of the Balkans and Central Europe is sure to be embroiled in war, pestilence and famine”; invoking the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse: War, Pestilence, Famine, and Death.

Beaverbrook played an exceptional role in both wars. He was Minister for Information in the First (a war he bitterly regretted, believing no British interests were threatened and that it was caused by secret promises made to France) and in the Second he became Minister for Aircraft Production: in this role he helped win the Battle of Britain, true to his vision of a fortress island. Rothermere’s pro-Appeasement stance, on the other hand, was more tainted by his political sympathies.

Rothermere believed “The sturdy young Nazis are Europe’s guardians against the Communist danger,” and he was a supporter of Mosley: he gave Mosley a weekly page for Blackshirt material in the Sunday Dispatch. Mosley found the paper’s coverage a mixed blessing, and in May 1934 he wrote to the editor:

All this human interest business – “Blackshirt patting head of mastiff ”; “Come to the cook house door”; “Girl fencers” etc – cuts no ice for the purposes of our organisation, and I imagine are liable to bore your public. It may have been a good thing to do it for the first week or two in order to show that Blackshirts have no horns or tails, but beyond that it serves no good purpose and may even do harm.

Rothermere’s flagship paper, The Daily Mail, was also strongly pro-Mosley; so much so, that in January 1934 it carried an illustrated piece by Rothermere himself, with the headline “Hurrah for the Blackshirts.”

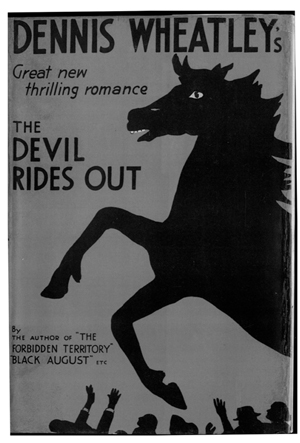

And so it was that on Halloween 1934 the Mail began a thrilling new serial novel (“Startling! Provocative! Romantic!”), about a struggle to avoid a new war with Germany. It was The Devil Rides Out, by “master of sensation” Dennis Wheatley.

*

“The Duke de Richleau and Rex Van Ryn had gone into dinner at eight o’clock,” it begins, “but coffee was not served until after ten.” Continuing the formula established in the first two Richleau books, one of the chums is in trouble and misses their reunion dinner. This time it is Simon Aron, “a young man brought to the verge of madness by his greed for gold”: he has fallen in with Satanists in the hope of obtaining clairvoyant powers to play the stockmarket.

After dinner, Rex and the Duke are driven to St.John’s Wood in the Duke’s Hispano, where Simon has leased a house. Anthony Powell writes of the area’s “Victorian disrepute as a bower of love nests and houses of assignation,” and its “tradition of louche goings-on”. William Sansom expands: it is “bizarre and dramatic … hushed … [with] conservatories, thick bushes, covered drives and reticent windows … The Wood … among the decorative lilacs and laburnums, was discreetly orgiastic. Relics of this time are still to be seen – a number of high front garden doors, stoutly placed between pillars surmounted by eagle or pineapple, still have peepholes.”

This is just the place for Wheatley-style luxury Satanism, and for Wheatley’s readers the very words “St.John’s Wood” have acquired an aura. Like the words “Hoyo de Monterrey” and “Imperial Tokay”, the magic of Wheatley is upon them.

Simon’s house is at the end of a cul-de-sac, in reality Melina Place. The doors set in the street wall, some of them leading straight into entrance halls, add to the ambience of leafy seclusion and slightly sinister privacy. The upper storeys are visible above whispering trees, and it is in one of these upper storeys that Simon has built an astronomical observatory with a pentagram on the floor.

Politely gatecrashing Simon’s party, Rex and the Duke meet the Satanists. One of these is the lovely Tanith, with whom Rex falls in love, but the others are an extraordinary bunch: like the Napoleonic marshals that Wheatley collected in later life, they would make a fine set of porcelain figures. There is a “Chinaman” in Mandarin costume; an albino; an Irish bard with a kilt and a pot belly; a “Eurasian” with only one arm, the left; a red-faced “Teuton” with a hare lip; a “Babu” Indian; a scraggy American woman with beetling eyebrows that meet in the middle; an elderly French woman with a beaky parrot nose who smokes cigars; and a man with a mutilated ear, Castelnau, a French banker who introduced Simon to Satanism.

Their grotesque qualities show a simplistic characterisation of evil by physical disability, and it is also noticeable that most of them have the misfortune not to be English. The fuller significance of their physical idiosyncrasies is probably the popular Adlerian psychology of the inter-war years. Alfred Adler believed that inferiority complexes were a driving force in human nature, an idea which spread into the saloon bar wisdom that Napoleon and Hitler caused trouble because they were short. Similarly, Wheatley’s friend Anthony Powell wrote in his notebook “No doubt it was Tamerlaine’s bad leg that made him such a nuisance to the world.”

The leader of the Satanists is Damien Mocata, a defrocked priest whose physical features – bald head and hypnotic eyes – were based on Crowley, while his refined fruitiness and preciousness probably owe something to Summers. “He does the most lovely needlework,” Simon explains:

… petit point and that sort of thing you know, and he’s terribly fastidious about keeping his plump little hands scrupulously clean. As a companion he is delightful to be with except that he will smother himself in expensive perfumes and is as greedy as a schoolboy about sweets. He had huge boxes of fondants, crystallized fruits, and marzipan sent over from Paris twice a week when he was at St.John’s Wood.

Now and then he has strange fits that send him out on missions unknown, returning unshaven and stinking of drink in torn clothes, as if he “had been wallowing in every sort of debauchery down in the slums of the East End.”

Mocata’s background – half-Irish, half-French – is in keeping with Catholic diabolism, since France was thought to be the place where Satanism flourished. However, his name, which now seems so perfectly part of his character, is about something else again: it is a distinguished Portuguese Jewish name, predominant in the London gold market since the seventeenth century, and evidently part of Wheatley’s heightened consciousness of Jews. A Thirties piece in the National Socialist League Monthly – unsigned but seemingly by William Joyce, better known as Lord Haw-Haw, whom we shall meet soon at one of Wheatley’s parties – complains about the financial power of the “Rothschilds, Sassoons, Mocattas, and Goldsmids”.

Rex and the Duke rescue Simon with a sock on the jaw. Getting him into the Duke’s treasure-packed Curzon Street flat, with its ikons and Buddha and ivories, the Duke first hypnotises him and then places a supernatural charm around his neck to keep him safe. In one of the stranger moments in Thirties fiction, it is “a small golden swastika set with precious stones”. “He’ll be pretty livid,” says Rex: “Fancy hanging a Nazi swastika round the neck of a professing Jew.”

The Duke explains that the swastika is “the oldest symbol of wisdom and right thinking in the world … used by every race and in every country at some time or another.” The swastika was still not as associated with Nazism as it has been since the War. As an Eastern charm, the swastika appeared on the books of Kipling (and, perhaps less innocently, it was given away as a lucky watch fob by Coca-Cola, who later sponsored the Berlin Olympics).

The Duke’s comments are not pro-Nazi: he says that although “the Nazis bring discredit on the Swastika, as the Spanish inquisition did upon the cross, that could have no effect upon its true meaning” (and Wheatley later propagates the idea that Nazi swastikas go “the wrong way”, like the Christian cross inverted; this is not very convincing, because ancient swastikas go both ways, but it is an attempt to reinforce the idea of Nazism as evil).

Germany is, however, specifically exonerated from having caused the First War. “I thought the Germans got a bit above themselves,” says Rex mildly, to which the Duke says “You fool! Germany did not make the War. It came out of Russia.” It was caused by Rasputin, in his role as Black Magician. This exemption from blame is part of the book’s central message: to borrow a phrase from Noel Coward, “Let’s not be beastly to the Hun.”

Now Mocata and the Satanists are trying to cause another war. “The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse,” says the Duke: “War, Plague, Famine and Death. We all know what happened the last time those four terrible entities were unleashed to cloud the brains of statesmen and rulers”; “… if they are loosed again, it will be final Armaggedon”; “to prevent suffering and death coming to countless millions we are justified in anything.”

Wheatley’s earlier title for the book was Talisman of Evil, and the Satanists plan to start the War by finding the Talisman of Set, a mummified Egyptian phallus belonging to the god Set: “a forerunner of the Christian Devil, Osiris’s younger brother.” If they can get their hands on this cigar-like object then (as Wheatley was able to inform newspaper readers) “those dread four horsemen would come riding, invisible but all powerful, to poison the thoughts of peace-loving people and manipulate unscrupulous statesmen, influencing them to plunge Europe into fresh calamity.”

*

As we have seen, Crowley felt his ‘Guardian Angel’ Aiwass was a version of Set, and he thought his “Aeon of Horus” would be the era of glorious war. Crowley liked to believe the publication of his books had caused wars: successive editions of The Book of the Law had caused the Balkan War, the Great War (“the might of this Magick burst out and caused a catastrophe to civilisation”), and later the Sino-Japanese War and the Munich crisis.

Wheatley’s novel was in tune with more than he fully understood, and he was getting extraordinary mileage from a smattering of occult knowledge. The Duke’s great spiel about magic1, repeated almost verbatim in later books, begins with the reality of hypnosis. It moves down a slippery slope to telepathy, then the powers of the human will, and before long the reader is plunged into the conflict between the forces of Eternal Light and Eternal Darkness.

Many occultists began with Wheatley’s books, although they may not always admit it. From The Devil Rides Out alone, the main planks of an occult worldview are clear: mind rules matter; spirit is transcendent; the human soul is eternal; we move through successive incarnations, “towards the light”; and there are “Hidden Masters” and “Lords of Light,” who tend to be Tibetan. The theosophical and Gnostic elements in all this come largely from Maurice Magré’s 1931 The Return of the Magi, which Wheatley read, with more archaic and picturesque details picked up from Grillot de Givry’s 1931 Witchcraft, Magic and Alchemy.

Wheatley’s writing tends to be research-heavy, and this research plays a special role in the occult books. The Devil Rides Out’s encyclopaedic packing with occult lore is so insistent that not only do readers learn about the astral plane, elemental spirits, the inner meaning of alchemy, familiars, grimoires, scrying, and the rest, but it tends to cause a suspension of disbelief. It is also richly atmospheric, with the Golden Dawn grades – Ipsissimus, Magister Templi, Neophyte, Zelator and so on, – and “passing the Abyss”, the “dispersion of Choronzon”, “St.Walburga’s Eve”, the “Clavicule of Solomon”, “Our Lady of Babalon”, and what-have-you.

Within the book’s occult framework, Wheatley had now found his central idea: that of Manichaeanism, the conflict between the forces of light and dark, or absolute good and absolute evil. Umberto Eco describes the James Bond books as Manichaean, but the universe of Wheatley is literally Manichaean in the theological sense. The Duke de Richleau explains it, and Richard and Simon complete his explanation: “Surely you are proclaiming the Manichaean heresy? …” “Even today many thinking people … believe that it holds the core of the only true religion.”

Back in the fourth century, Saint Augustine had rejected Manichaeanism as psychologically inauthentic, in the sense that everyone can do some bad and some good. In the words of T.S.Eliot: “pure villainy is one kind of purity in which it is difficult to believe. Even the devil is a fallen angel.” But this all-out conflict between good and evil is useful for pulp fiction and propaganda. It corresponded to something intrinsic to Wheatley’s psyche, a tendency to ‘split’ the world into good and bad, and a lifelong ability to see things in reassuringly simple, black-and-white terms; or perhaps an inability to see them otherwise.

*

Occult fiction had tended to be a relatively subtle affair, like the quality ghost story, but Wheatley dragged it firmly into the thriller genre, combining black magic with hand grenades and car chases. So generously thrilling is The Devil Rides Out, in fact, that it ends on a plateau of rolling climaxes, any one of which would be good value in a lesser book.

First comes the siege in the pentagram, borrowed from the occult fiction of William Hope Hodgson. The friends are holed up in a pentagram on the floor of a country house library, and their ordeal ends with an attack by the Angel of Death, who rides a black horse and can never return empty handed (borrowed from an anecdote of a similar siege in Alexander Cannon’s 1933 The Invisible Influence, a book the Duke recommends to Rex). It is only defeated by the Duke’s pronunciation of two lines from “the dread Sussamma ritual” (again borrowed straight from Hodgson, along with “ab-humans” and “saiitii”).

As if that wasn’t enough, the Eatons’ little daughter Fleur is then snatched by the Satanists, who intend to sacrifice her. The friends track Mocata and his associates to an empty Satanic temple in Paris, only to be mistakenly arrested as Satanists in a French police raid. Escaping after a fight, they follow Mocata in an aeroplane chase to a Greek monastery where the Talisman is hidden. Here, “the perverted maniac playing the part of the devil’s priest would rip the child open from throat to groin while offering her soul to Hell”.

The Black Art (1936) by Rollo Ahmed.

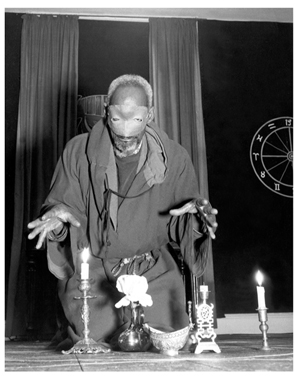

Rollo Ahmed performing a ritual.

“The lovely Tanith.”

Mocata is just raising the knife when Marie-Lou remembers The Red Book of Appin (taken from Montague Summers). She has seen it in a dream, and she utters a sentence she saw written in strange characters: “They only who Love without Desire shall have power granted to them in the Darkest Hour”. All Hell breaks loose: the ground is rocked as if by an earthquake, the crypt spins, the Talisman of Set falls uselessly to the floor. The phallic power of the Satanists has been defeated by the power of love.

“Time ceased, and it seemed that for a thousand thousand years they floated.” The friends find themselves back at Cardinal’s Folly, as if it had all been a shared dream. Only the fact that the Duke still has the phallus of Set, which he throws in a furnace, suggests it has been something more. With the world moving steadily towards war, escaping the process of time was a popular motif in Thirties fiction – most famously in Lost Horizon (1933), written by Wheatley’s friend James Hilton, with its fabulously timeless Tibetan-style kingdom of Shangri-La – and the Duke explains in the book’s closing line: “it is my belief that during the period of our dream journey we have been living in what the moderns call the fourth dimension – divorced from time.”

*

It has been widely observed that the crisis of the Thirties led many writers “to Moscow or Rome”, to Communism or the Church, and Wheatley’s turn to supernaturalism is a variant of the latter. Given the link between occultism and right-wing thinking, it is oddly appropriate that the greatest occult novel of the twentieth century should have a subtext of peace with Nazi Germany, and have first appeared in the pro-Blackshirt Daily Mail. In all his interviews about his career and the genesis of The Devil Rides Out, Wheatley never once mentions the salient fact that it is an Appeasement novel.

Wheatley’s masterstroke was to put a disclaimer at the front, insisting that he had never been to an occult ceremony and warning readers not to dabble. Framing the alleged reality of Black Magic (“still practised in London, and other cities, at the present day”) so negatively was more powerful and convincing than any other stance on it could have been.

Wheatley’s life would never be quite the same again. He had hit the occult vein that would immortalise him in popular culture, like Agatha Christie’s demon brother. Wheatley was far from confident about what he had done: he worried that there was too much research showing in The Devil Rides Out and that “the data was overwhelming the plot”, not realising that the “data” was so atmospheric in itself that for many readers it made the book. He originally put a questionnaire at the back of the first edition (page 329, excised from most copies), asking readers if they thought there was too much complicated background in the way of the plot. “Or do they find subjects such as the occult lend additional interest to thrilling action?”

Reviews were largely favourable. Compton Mackenzie quibbled Wheatley’s Latin and his haziness about theology but admired the “cracking pace.” The reviewer in the Times Literary Supplement conceded it was “a good story” but complained that the powers of evil were not evil enough. “There is no torture,” he wrote, and as for the “boiled baby”, it “appears to have died naturally.” TLS reviews were anonymous in those days, but this man must have been the paper’s Resident Fiend.

*

Wheatley soon discovered that his occult books drew a different postbag from the rest. A man in Edinburgh signing himself “The Christ” wrote a series of letters about the Book of Revelations. Another wrote from Broadmoor to say that since the worship of Christ had failed to stop wars or improve anything over the previous 2000 years, it was time we gave the Devil a chance.

Wheatley seems to have had little sense of whether writers were pulling his leg. One man wrote to quibble the location of the Satanic temple in St.John’s Wood, and said it was on the other side of the Finchley Road (“I went there to a meeting some little time ago, but I suppose you thought it policy not to give away its actual situation in your book”). Wheatley could now cite this letter as further evidence for the reality of Satanism.

One of his most involved correspondences came from a woman in Essex who claimed to have been sold to the Devil by her father (or mother: Wheatley isn’t quite consistent in his telling of this story, but there does seem to be a real woman behind it). Wheatley met her, and she told him she was unable to go into a church without feeling sick, and that she had to be careful not to be angry, because bad things would happen to people if she wished them ill.

Wheatley thought she was like someone resigned to having a rare and incurable disease. She made no effort to borrow money or seek Wheatley’s help in having anything published. “I am convinced that there was nothing whatever evil about her,” Wheatley remembered, “but it certainly seemed that she was a focus for evil and she spoke of her sad fate with such simple candour that I found it extraordinarily difficult to believe that she was romancing deliberately.” Her story later became Wheatley’s inspiration for To The Devil – A Daughter.

*

Crowley had written to Wheatley since their lunch at the Hungaria. “I would love another chat, esp. about Magick, as you’re on a book; I’d like to hear what you think of mine.” Wheatley was not keen to continue his acquaintance with Crowley, and made the excuse of being too busy with work.

Having failed to make a useful disciple of Wheatley, Crowley’s correspondence took on a more jibing quality. “Most ingenious,” he wrote at one point, “but really a little Ely Culbertson, to advertise your love of rare editions in a thriller blurb!” (Ely Culbertson was an American bridge player, whom Crowley evidently found vulgar).

Now, the day after the first Mail instalment appeared, Crowley wrote him a brief note on the letterhead of the Hotel Washington, Curzon Street, Mayfair. “Dear Dennis Wheatley,” it said, “Did you elope with the adorable Tanith? Or did the witches get you Hallowe’en?”

1 In Chapter Three, ‘The Esoteric Doctrine.’