Wheatley was an infant during the Boer War, an ugly war which killed over twenty thousand British soldiers and began to break the Victorians’ faith in the Empire. The major event in the public mind was the siege of Mafeking, where an outnumbered and under-equipped British garrison of soldiers and trapped civilians held out from October 1899 to May 1900, eating their horses and printing their own currency and stamps. They were shelled by Boer artillery every day except Sundays, when they listened to their military band and played cricket.

The conflict was keenly followed in Britain, and when Mafeking was saved there was jubilation on the streets of London. “Mafficking” (to celebrate wildly) became a verb of the time, and The Relief of Mafeking was the only day that Wheatley’s father ever came home drunk. The walls of Wheatley’s nursery were papered in a pattern of khaki on white, and showed scenes from the Boer War. Wheatley always remembered a British soldier walking forwards under a white flag of truce, but being gunned down regardless by the dishonourable foreign Boer. This was the wallpaper of Wheatley’s earliest years.

*

Wheatley’s parents had a second boy when Wheatley was less than two, but he died while Wheatley was still too young to remember him, choked by a whooping cough that his parents believed he caught from Dennis.

Wheatley took better care of his doll, a little man called Charlie who wore a blue velvet suit. Long before the characters of his fiction – novelistic dolls and puppets of whom an interviewer noted that he talked about them “in such affectionate, avuncular terms that one almost expects that at any moment they will be shown into his study” – Wheatley had a vivid imaginative relationship with Charlie. When the family were about to set off on holiday, and their trunks were loaded onto the horse-carriage that was taking them to the railway station, Wheatley suddenly needed to know where Charlie was, and began to scream that Charlie would suffocate, until the trunks were unpacked and Charlie was rescued. Charlie spent the rest of the journey in Wheatley’s overcoat pocket, with his head sticking out so he could breathe.

Wheatley was a wilful child, capable of shouting, repeating a request endlessly, or even lying flat on his back and screaming until he got his own way. Had his father been anything like the ogre that Wheatley imagined, this behaviour might have been knocked out of him, but it never was. Wheatley’s inability to like this well-meaning man is the saddest aspect of his childhood. As he grew up he found his father boring, business-obsessed, humourless, and unread, but almost from the beginning he found him frightening.

His father’s eyes were round, bland and inscrutable, so it was impossible for Wheatley to tell what he was thinking. His expressionless stare would terrify Wheatley, who feared that he had been found out doing something wrong. Wheatley even wondered if his father’s strange, implacable eyes had hypnotised his mother into marrying him.

Not that his father always helped his own cause. Before Wheatley could read, he took immense pleasure in being read to by his mother or his nanny. His pocket money was a penny a week, which he generally spent on sweets, but one day when he went to the shop with his nanny, his attention was caught by the boy’s paper Chums. As Wheatley remembered it, the characteristically thrilling cover picture showed a Red Indian sneaking up on an unwary cowboy. The urge to hear the story behind this anxious scenario, and to know what happened, was so strong that it won out over Wheatley’s liking for sweets, and he invested the whole of his penny in that week’s copy of Chums.

Wholesome, patriotic and deliberately “decent”, Chums was widely regarded as the best of the boys’ papers at the time. It was packed with outdoor adventure, cliff-hanging action, and plucky ruses for outwitting malevolent natives. It also carried educational features on music and industry, and it had a social conscience, with photo-illustrated pieces on the education of poorer chums in the East End (all boys were generically ‘chums’ as far as Chums was concerned, so a socially aware piece on Jewish boys in Britain, for example, was about “Jewish chums”).

A hundred years on, it is still striking what a quality paper Chums was, with articles like ‘A Visit to Admiral Markham’ (in the series ‘Notable Men with Private Museums: and Stories of How They Founded Them’). Self-improvement was the order of the day, whether ‘From Street Arab to Author’ or ‘From Pit to Parliament’, but it was never easy, as in ‘The Struggles of a Great Violinist: Mr.Tivadar Nachez’s Rise to Fame’.

A typical Chums feature might be ‘Queen Victoria’s Life in Stamps: Portraits from all Parts of the Empire’ (something Wheatley collected in later life, displayed under glass), and the paper was interspersed with cartoons, perhaps featuring visual puns, or talking oysters. Other pictures almost defy parody, like ‘The Joy of Life’, in which a female elephant, wearing a spotty dress, is jumping up and down while waving a Union Jack in her trunk. And above all, Chums carried cliff-hanging stories, like the irresistibly titled ‘Above The Clouds With A Madman: Professor Gasley’s Weird Voyage.’

The covers were even more cliff-hanging than the contents. “Percy … hung and swayed over an abyss of death” is the picture on one, while on another “The Gorilla was now less than six feet away,” or “Shielding the Young Trooper’s Body With His Own, He Turned to Face the Savages.” It was all-important to stick together, like the two Englishmen who stand back to back with a gun and sword as a crowd of armed Chinese attacks them, and it was hardly less important to do the decent thing, like giving water to a wounded Boer (‘An Enemy in Need’).

Wheatley never found out what happened to the unwary cowboy. When he got home, his father caught sight of the comic and made a terrible error of judgement. Bearing down with his frightening eyes, he snatched it away, gave the nanny a dressing down for letting him buy it, and put it on the living room fire, where little Dennis had to watch it burn.

Wheatley’s father must have thought it was a “penny dreadful”, like the lurid vampire and Ripper shockers from a few years earlier, but it was as unjust as if a 1950s father had snatched and burned a copy of The Eagle. It seems to have been the injustice that shocked young Wheatley as much as anything else. He intuited Chums was “good” (the pictures, for one thing, were like his stirring nursery wallpaper) and he knew a wrong had been done, but he was too young to put it into words, and in any case he was powerless. And that was it between Wheatley and his father: “this sudden harsh and unjustifiable punishment started a festering sore that was not to be healed finally for nearly a quarter of a century.”

When he grew a little older, the Chums annual was Wheatley’s favourite Christmas present, year after year. Seventy years later he was still defending it: “I can recall no story in it which did not encourage in young readers an admiration for courage, audacity, loyalty and mercy in the hour of victory.”

One of the most arresting aspects of Chums is its small adverts. The firm of Gamages, for example – the once great Holborn department store – seems to have appointed itself as armourer to the nation’s youth. It offered the ‘Son of a Gun’ water pistol which “protects bicyclists against vicious dogs and footpads; travellers against robbers and roughs; houses against thieves and tramps” (possibly it had to be filled with ammonia; whatever the secret was, “full directions will be found on the inside of the box.”) Still in keeping with the hazardous, conflict-ridden nature of the Chums world, Gamages also offered an alarming range of swordsticks. “Strong bamboo, stout blade” could belong to any reader for 1/6d including postage, while “Choice bamboo, mounted nickel silver, stout square blade, 26in. long (a very neat stick)” was 2/3d. Wheatley grew up with a liking for swordsticks, and owned several as an adult.

*

Wheatley’s father was not a reader and he considered fiction, in particular, to be a waste of time. In contrast, his more cultivated mother was an avid reader, so the realm of books and stories was more maternal in its early associations, and belonged to the Baker rather than Wheatley side of his family.

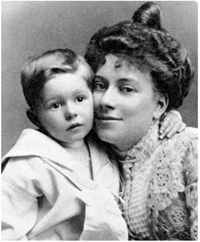

Wheatley regarded his mother as a great beauty when he was a child. He grew less fond of her as he grew up, and his opinion of her features changed accordingly (“I now know that her features, though regular, were too coarse for her ever to have been really lovely”). As an adult, he looked back on her as snobbish and lazy, although he remembered her lively mind and sense of humour, and he conceded that her charm led people to think of her as a socially distinguished woman – “other than the few who were capable of detecting her occasional middle-class lapses”.

There is probably more tender-hearted romance in Wheatley’s novels than there is in the work of any comparable male thriller writer, and the fact that they appealed to women as well as men would increase the immense readership for his work. As a small boy Wheatley was very close to his mother, who would let him help her choose her clothes and make decisions at the dressmaker. In turn, he seems to have known how to get round her: she gave him his first piano lessons, and one day when he was playing badly, she tapped him on the fingers with a pencil, at which he began to sob and howl. “Come, darling, come,” she said, hugging him, “I couldn’t possibly have hurt you.” “No,” said Wheatley, “but you hurt my little feelings.”

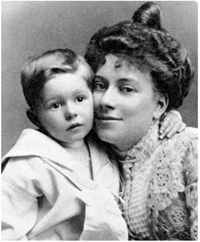

Resolute little chap: Wheatley circa 1900.

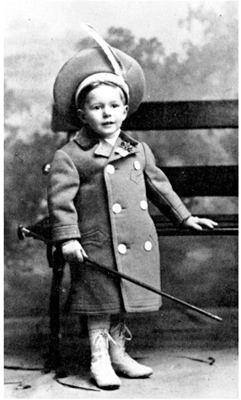

Bric-a-brac: the interior of Aspen House.

Wheatley as a cadet on HMS Worcester.

Wheatley had a little sister, Muriel, who was plain but had an abundance of golden hair: Wheatley’s father, in an affectionate and playful mood, would pretend to lose gold sovereigns in it. Rather than little sisters, Wheatley had a lifelong liking for girls on the ‘big sister’ model, the first of whom was a neighbouring girl named Dorothy Sharp, five years older than Wheatley – nine to his four – who lived nearby. Wheatley’s mother enrolled him in a kindergarten where Dorothy was also a pupil, and it was arranged that she would call for him every morning and escort him there. “I became very fond of her”, writes Wheatley, “in the way that one is of an elder sister.”

It was at the kindergarten that romantic love first struck for Wheatley, with unhappy results. He became aware of two much older sisters, Janie and Honor, and he thought Honor was lovely, indeed “the most lovely person I had ever seen.” Still barely more than a toddler, Wheatley had romantic fantasies about Honor, in which he would rescue her from terrible Chums-style perils such as burglars and Red Indians.

Dorothy Sharp took Wheatley to the kindergarten, but it was his nanny who had to collect him and take him home again. One day his nanny was late, and Wheatley sat there miserably waiting for her: he had his overcoat and hat on, but he had not yet mastered the art of tying his bootlaces, which his nanny had to do. When Honor – entirely unaware of the role she played in Wheatley’s fantasy life – happened to come by and see this poor little mite sitting there so miserably, she asked what was wrong, and without any fuss she did his boots up for him. They had never spoken before and now Wheatley was confused, dumbstruck and generally mortified with “wonder, embarrassment, and shame”. It took him days to recover from this “shattering experience” – even as an old man he still remembered it with some intensity.

*

Wheatley had a strong sense of the two sides of his family as separate. His Wheatley grandmother Sarah was grim, ignorant, Low Church, strait-laced, and mean, but life was very different at Aspen House, where Grandfather Baker lived with his pictures and his orchids, along with four full-time gardeners. When he called on friends he would take orchids for their wives, bowing and producing them like a conjurer out of his bowler hat. On Sundays in the late summer and autumn he would invite twenty or thirty friends round to drink champagne, after which he would give away the produce of his garden.

Living nearby, the Wheatleys would go up to Aspen house two or three days a week. Wheatley always remembered the food: Grandfather Baker would have a steak or a Dover sole for his breakfast, and there would be high teas with eggs, kippers, or crab, followed by generous quantities (“masses”, writes Wheatley excitedly) of strawberries or raspberries with cream. Weekday dinners and Sunday lunches meant duck, salmon, pheasants, chickens and lobsters, ending with fruit and nuts after “rich puddings.”

Aspen house was filled with artworks and china, including a tea service that was said to have belonged to Lord Byron, a smoking outfit belonging to Napoleon, and the once famous mechanical singing bullfinch from the 1851 Exhibition, as well as a painting which had a working clock in it. The walls were completely covered with pictures, frame-to-frame. The overall effect was intensely cluttered and somewhat Continental in taste, with ormolu-mounted Buhl cabinets, endless vases and vessels, Dresden china groups, and glass display cabinets full of china and figurines.

Quite unlike the so-called country-house look, it must have been like living in a high-class department store, and it took twenty-one days of auctions to disperse Grandfather Baker’s collection when he died, beginning with a sale of pictures at Christie’s. Wheatley always looked back on him as the source of his own love of the finer things in life.

*

Things were less grand, but still comfortable, further down Brixton Hill at Wheatley’s parents house in Raleigh Gardens, towards Streatham, a large suburban semi-detached bought for them by Grandfather Baker, who had since relented about Dolly’s allowance.

At first the Wheatleys had only one servant, a girl of 20 named Kate. Wheatley’s mother could barely boil a kettle and never cooked, so Kate was up at six for cleaning, scrubbing and laundering. In the afternoon she was in her best outfit to attend on callers, before cooking the dinner, serving it, and washing up. She was paid a pound a month (about £60 now), and as a Christmas present she would be given material to make herself a new uniform.

Kate was a ‘general’, which is to say she did everything, until after Wheatley’s birth the family also took on her younger sister, which freed Kate for helping with Wheatley. Most local families had servants, and Wheatley felt sorry for the family of his friend Dorothy Sharp, who seemed to have trouble making ends meet and had only one servant, a slovenly teenage girl from Kent.

The Wheatleys were lucky in their neighbours. Next door lived the Kellys, and Wheatley thought of Charlie Kelly as a painter, which brought him into WYB’s circle, but this seems to have been a sideline; he was principally a toy importer. Kelly was a dwarfish man with a high voice and what Wheatley thought of as negroid features, and at Christmas he would sing “Negro ditties”. His little daughter was Wheatley’s first playmate, but unfortunately “ugly and stupid into the bargain.” On the other side was a widow, Mrs.Mills, who bought Wheatley toys, including a set of knights in armour. Looking back on them late in life, Wheatley characteristically adds “if such a set were procurable today I doubt its price would be less than £300.”

WYB’s household also included a housekeeper, Nelly Mackie, who may have been a relative; she always called WYB “Uncle”, and her son Laurence was thought of as a kind of cousin. She was an attractively plump woman in her thirties, and Wheatley came to think she may have been there primarily as company, and perhaps more, for WYB: “One of his dictums was that a girl should be ‘as fresh as a peach and as plump as a partridge’, and if that was his taste then the young Nellie Mackie may well have been a great source of pleasure to him.”

Laurence (“Laurie”, or “Cousin Los”) became like a much-loved elder brother to Wheatley, and when he was back from his boarding school, he would play with him in the garden – with what Wheatley later realised was kindness and patience, given their five year age difference – and tell him stories about the little people who lived in the rockery.

*

WYB’s garden – a small remnant of the much larger Roupell Park – came from the Elizabethan period. His mulberry trees were said to have been planted by Elizabeth, although Wheatley thought it was more likely they were from the reign of James I, who encouraged the planting of mulberries to build up a native silkworm industry. WYB’s garden seemed enormous to Wheatley. Beyond the lawn with the mulberry trees lay the peach house, the tomato house, two orchid houses and a couple of other hot houses. Further on were the orchards, the summer house, an archery target and a swing, and a walled kitchen garden. “What a feast of joys it was for any small boy to roam in on long summer afternoons!”

This sense of a lost Edwardian wonderland is pervasive in the early parts of Wheatley’s autobiography, inseparable from the Edwardian nostalgia just under the surface of his fiction. He remembers cakes from the once famous Buszards on Oxford Street, and magic lantern shows at parties.

There were rockpools to explore at the seaside, and he particularly remembered the Surrey countryside around Churt, where his father rented a cottage. It was still “entirely unspoilt” and “within the range of a morning’s walk there were not more than half a dozen modern houses”. Wheatley saw a profusion of wild flowers, which he was fond of as a child, coloured dragon flies hovering above bulrushes, and small waterfalls in a woodland stream. “For me the most lovely thing in nature is a woodland glade”, Wheatley thought, and despite his later travelling around the world “I still have no memories … which exceed in beauty those of the Surrey woods.”

The nostalgic tone continues when Wheatley talks about Brixton. It was still quite green in those days, although it also had Electric Avenue – the first street in Britain to be lit by electricity – and a couple of modern department stores, where customers’ money was spirited around the shop by a Heath Robinson arrangement of pulleys and wires: a container would rocket away and disappear into unknown regions, zooming back a few minutes later with the receipt and the change.

Wheatley’s doting parents often took him to a Mr.Treble’s photography studio, and in one of Wheatley’s favourite photos of himself he was posed in an eighteenth-century style three-cornered hat, of the kind worn by pantomime leads and Toby jugs; Wheatley thought of it as a “highwayman’s hat.” The past always seemed more picturesque.

*

Streatham was not a smart address. Journalist Olga Franklin wrote of a man she knew, “who had a dreadful secret … He was quite tormented by it. He roamed the world, living in Malaya, India, Japan, America … only not to be at home face to face with The Secret. One day the ugly truth came out. He had been born and brought up in Streatham.”

Bert Wheatley was working hard at the wine business, and in 1904 he was able to move his family to a less suburban house, still in Streatham but in a better neighbourhood. This was Wootton Lodge, which had a central building, two wings on either side, and a curving drive. Wheatley’s father modernised it and installed speaking tubes, so that servants in the basement could be spoken to without having to summon them by ringing.

All this social mobility had to be paid for, and Wheatley’s father was surviving far better than some of his uncles. Ne’er-do-well Uncle Johnny Baker wore loud check suits with extravagant flowers in his buttonhole and spent too much time at the races or entertaining chorus girls, and then let the side down by marrying a barmaid, who divorced him for philandering. WYB grew similarly tired of his dissipation, and pensioned him off on the condition he lived abroad.

One unfortunate incident involving Johnny was no fault of his own. At Aspen House was a large bulldog which was extremely fond of young Wheatley. One day Wheatley ran towards Uncle Johnny, and his expansive uncle snatched him off the ground and swung him up in the air. Springing to defend the child, the dog jumped at Johnny and sank its teeth in his chin: “as bulldogs are renowned for refusing to leave go,” says Wheatley, “the horrible scene that followed can be imagined.” Wheatley had no conscious recollection of this, but he became afraid of dogs and was never again comfortable with them. It seems to have become one of those things that we never remember and never forget.

Uncle Jess was harder working but came to a spectacular downfall. He was in charge of the shop at 65 South Audley Street, where his particular problem was the system of routine fraud and embezzlement, whereby chefs and other powerful servants would take a commission on everything that was supplied. If tradesmen refused to play, then the chefs and butlers could guide their masters’ accounts elsewhere, if necessary by serving bad goods and blaming the suppliers. Charging for goods not supplied was another long established custom, and chefs could insist on tradesmen adding a fraudulent ten or twenty pounds a month to their bills and splitting it with them. The strain of all this drove Uncle Jess to drink.

People are sometimes said, figuratively, to swing on the chandelier. One night Uncle Jess was literally swinging on the chandelier when he and it came crashing down on to the table below. That was the end; Ready Money sacked him from South Audley Street. He and his wife Emily were exiled to run a small grocery at St.Margaret’s Bay, near Dover.

One day in the 1920s, Wheatley himself was working in the South Audley Street shop, when a woman came in asking for his father; “a woman who would neither state her business nor go away.” Wheatley was called from his office, and saw “a small, faded, seedily dressed woman”, to whom he explained that his father really was out. Could he be of assistance? “Oh, Dennis,” she said, “don’t you know me? I’m your Aunt Emily.” A few years later she was dead.

*

Young Wheatley’s life continued happily at Wootton Lodge, untroubled by the business realities that kept it going. It had a bigger garden than their previous address, a summer house with coloured-glass windows and a greenhouse where orange trees grew.

The garden was the special domain of Mr.Gunn the gardener, “the ruler of this small boy’s paradise.” He found time to make Wheatley toy swords, and bows and arrows, and he was also a keen amateur “naturalist,” which in those days was a collecting activity. Gunn showed Wheatley how to catch and preserve butterflies, and he was sometimes allowed to go to Gunn’s house for tea, where he saw the birds that Gunn had stuffed and mounted, and his butterfly and beetle collections. Wheatley treasured the two glass cases of butterflies that Gunn gave him as Christmas presents.

But a shadow was soon to fall across this small boy’s paradise, and Wheatley would soon have tribulations of his own to deal with. The time had come for him to go away to boarding school.