2

THE PROBLEM OF PARIS

AT THE HEART OF EVERYTHING Louis Napoléon did and thought about was the question of Paris. Because of his long exile, it was not a city he knew well or even particularly liked (London was much more to his personal taste), but he knew that the success of his regime would be measured in the way that his policies played out there. Like all dictators, he feared his capital’s restive energy and combustible proletariat, those forces that had ignited the revolutionary explosions of 1789–1794, 1830, and 1848 and that could not be controlled by ordinary policing. He had the sense to understand that jobs were the key to order and loyalty: “I would rather face a hostile army of 200,000 than the threat of insurrection based on unemployment.”

Paris was the key. Aside from its political volatility, the place was in a dismal state of physical decay, its oases of splendor such as the Louvre and the Arc de Triomphe surrounded by a fetid wilderness of filth, stench, and crime, pitted with noxious warrens of tortuous backstreets cramped with decrepit tenement housing and swarms of wretched humanity. The population had almost doubled since 1800. Major outbreaks of cholera, spread by contaminated water, had claimed tens of thousands of lives in 1832 and 1849. Traffic ground to a halt in daily gridlocks as the infrastructure creaked and cracked. The sum of it was a crisis that could only get worse.

There had been much tinkering with the problem over the years, and many grand reports and bold proposals had been submitted. In the 1780s Louis XVI had mapped the city and decreed a code specifying approved dimensions for new buildings; in 1793 a commission was established to address matters of congestion and street width. A decade later, Napoléon constructed the arcaded Rue de Rivoli, running from the Place de la Concorde alongside the Tuileries and the Louvre. Under Louis-Philippe, in the wake of the 1832 cholera epidemic, further practical initiatives were undertaken. The comte du Rambuteau, prefect of the Seine and therefore in effect Paris’s mayor, had commissioned a new Hôtel de Ville, completed work on the Arc de Triomphe, and built new sewers and water conduits as well as demolishing buildings in a particularly rough area of the Right Bank to create a long, straight, broad avenue, running east-west from Les Halles to the Marais and lined with gaslights and planted with trees: today it is still known as the Rue Rambuteau.

However, Jacques Lanquetin, a veteran of Waterloo and a wine merchant who led the city council from 1848 to 1852, urged something even more radical and visionary. Piecemeal or isolated schemes were no good, he insisted, and at a width of 12 meters (40 feet), the Rue Rambuteau was too narrow for the pressure of its regular traffic; plans for the city’s future streets had to be wider, integrated, and systemic in order to be effective. The advent of the railways was about to transform demographics and necessitate entirely new lines of communication and circulation to and from the terminals. Tolls should be abolished and the food market of Les Halles moved out of the center, but at this point Lanquetin was shouted down: where would the money come from? Paris prided itself on balancing the books and living off its revenues, chiefly taxes on property and levies (known as octroi) on goods entering the city. What was being proposed would entail massive expropriation and the payment of equally massive compensation, all to be negotiated through complex legal process; without imprudently large loans, the sums simply did not add up.1

Louis Napoléon was having none of it: a drastic remedy was required, and there was no time to lose. In brief, he used his power grab to dismiss Paris’s timid naysaying governors and ensure that legislation simplifying compulsory purchase was waved through (basically, the financial terms were generous, but there could be no appeal). Capital could be raised by borrowing from the banks—themselves liberalized—on the economic basis that the development would provide employment and raise rents and land values, thus generating growth and returns. Louis Napoléon believed that Paris had a lot to learn from Nash’s grand master plan for London, but the British had to be trumped—on his watch, he would aspire to make the French capital rank again as the most beautiful and exciting city in the world.

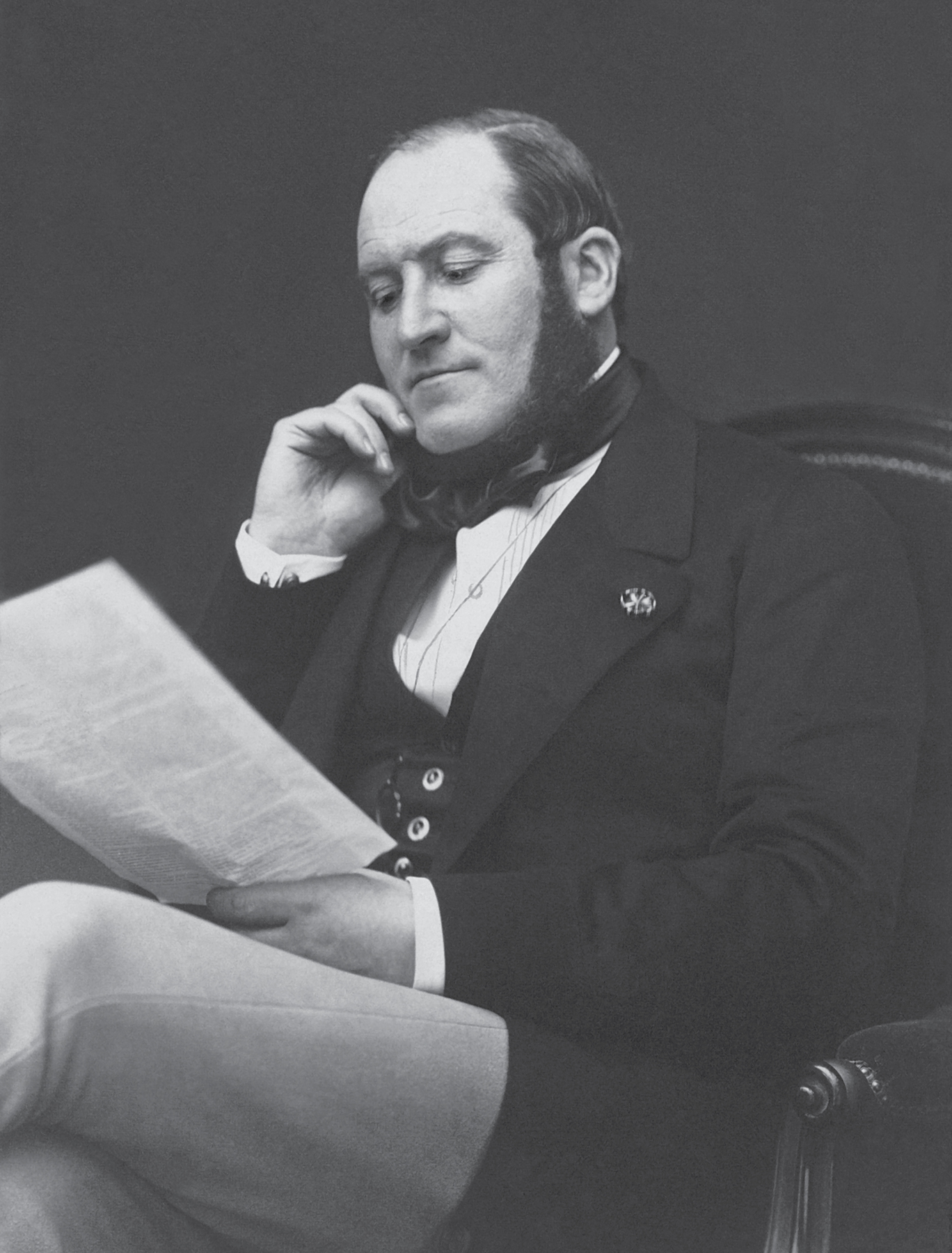

Where was the deputy who could be entrusted with this daunting brief, the fine details of which he could not attend to himself? Not, certainly, Prefect Rambuteau’s successor, the stolid and legalistic Jean-Jacques Berger, who would be let go. It was in Bordeaux that the regime found its man: here in 1852 Louis Napoléon had made a highly successful official visit, immaculate down to the last fluttering pennant and trumpet fanfare, all organized by the prefect, a career civil servant named Georges-Eugène Haussmann, whose record was impeccable.

BORN IN 1809, HAUSSMANN SPRANG from a solid and steady middle-class Protestant Alsatian background; his forefathers included several senior public servants of a Bonapartist persuasion. Imposingly tall, handsome, and muscular, he had nevertheless suffered in his Parisian childhood from choking asthma, an affliction that might go some way toward explaining his subsequent obsession with clearing blockages and opening up airflow. He enjoyed a progressive education in a fashionable lycée, where he numbered the poet and dramatist Alfred de Musset among his friends. His own bent was musical—he was an accomplished cellist and lifelong opera fan—but he chose to study law at the Sorbonne before entering civic administration. Working his way through several provincial postings, he proved himself a supremely disciplined and organized pragmatist, as charming as he needed to be in pursuit of his goals, but signally lacking in tact or respect for petty protocol.2

In his memoirs, Haussmann related that he received the telegram announcing his appointment at a civic dinner. “I took care to hide my great surprise,” he said, quietly folding the paper into his pocket and informing the gawping company that it was “nothing serious.”3 But he must have been expecting something: Louis Napoléon’s people had long earmarked him as potentially useful, and he had been subject to a long, secret grilling by Interior Minister Persigny, whose main concern was to test the extent of Haussmann’s loyalty to the imperial idea. Persigny remembered the meeting vividly:

I had before me one of the most extraordinary types of our time. Large, powerful, vigorous, energetic, and at the same time sharp, shrewd, resourceful, this bold man was not afraid to show himself for what he was. With visible self-satisfaction, he put before me the highlights of his career, sparing me nothing: he would have talked for six hours without stopping as long as it was on his favourite subject, himself. Far be it from me to complain of this tendency. It revealed all the sides of his strange personality. Nothing could be so curious as the way he told me about all his titanic struggles… above all with the municipal council of Bordeaux. While he was informing me in the greatest detail of the incidents in his campaign against formidable adversaries in the municipality, the traps he had set them, the precautions he had taken to make them fall into them, then the stunning blows he had given them once down, his face lit up with triumphant pride.

While this absorbing personality spread itself before me with a sort of cynical brutality, I could not hide my keen satisfaction. To fight against the ideas, the prejudices, of a whole school of economics, against the shrewd, sceptical men of affairs come for the most part from the lobbies of the Bourse or the corridors of the courts, and not very scrupulous about the means they used, here was the man for me. Where the most intelligent, clever, upright and noble men would inevitably fail, this vigorous athlete, broad-shouldered, bull-necked, full of audacity and cunning, capable of pitting expedient against expedient, setting trap for trap, would certainly succeed. I rejoiced in advance at the idea of throwing this tall tigerish animal among the pack of foxes and wolves combining to thwart the generous aspirations of the empire.4

Haussmann was never officially named the mayor of Paris because Louis Napoléon was wary of such a title; it would have been too dangerous to give any single person the power that it implied. Instead, like his predecessors, he was called prefect of the Seine, ranking equal alongside the prefect of police of the Seine, with whom lay matters of security and the prerogative to arrest, impound, and enforce. But that suited Haussmann, who had other ways of dealing with obstacles: he did not want or need to get involved with the police or even with politics, with its inevitable negotiations, compromises, and retreats. His sole interest was organization and efficiency, his genius being limited to the logical and methodical procedures whereby one could move from A to B until one reached Z. Problems were there to be solved; opposition was there to be ignored or circumvented. His talents were purely managerial: he had no partisanship, no imagination. Haussmann was the emperor’s servant, empowered to get a tough job done, and that was the sum of it.

On June 29, 1853, the day that Haussmann was officially installed into office, he attended a formal luncheon, followed by his first private interview with Louis Napoléon. Here Haussmann claimed that he showed his mettle at once, rejecting the idea of instituting an official commission of planning and making it plain that he intended to let the municipal council lie fallow. The only seal of approval he recognized was the emperor’s. All he wanted was some basic instructions. At this point Louis Napoléon produced a map (sadly, it has not survived) he had roughly sketched out in blue, red, yellow, and green crayons indicative of priorities, outlining a network of new boulevards that would cut through the city’s clogged arteries and allow it to breathe more freely. Through the next seventeen years this chart would remain the template.

Henceforth, Louis Napoléon and Haussmann would meet constantly. No record of their conversations survives, and posterity must depend on Haussmann’s unabashedly self-serving memoirs for evidence of how they operated. However, it was said that only the prefect of police had the same level of immediate regular and confidential access to the imperial inner sanctum and that the intimacy of their daily meetings whenever Louis Napoléon was in residence in Paris became a source of resentment to other ministers and supplicants. Both in their different ways possessed of cool and inscrutable personalities, their relationship remained purely professional, not least because Louis Napoléon’s ghastly wife thoroughly disliked Haussmann, thinking him vulgar or at least insufficiently groveling. Haussmann did not care: to his credit, he was never a courtier, always a civil servant, and if the two men did not embrace each other, they did not quarrel either.

Haussmann’s working habits in the Hôtel de Ville were rigorously disciplined, starting at 6 A.M. The great majority of his day was spent sitting calmly in his sumptuously appointed office, patiently attending to detail and holding brief decisive meetings: not one to waste words, he relied on his phenomenal memory and the efficiency with which he processed the paperwork. Preferring not to involve himself unnecessarily with the humanity of the streets, he paid only the minimum of visits to construction sites and never left his carriage to wander or chat: what the man on the Courbevoie omnibus felt about things meant nothing to Haussmann. In the words of historian David P. Jordan, “He had little tactile contact with the city… it was not a living organism with habits: Paris, had, for Haussmann, needs but no desires, limbs and arteries, a digestive system, but no heart.”5

With his staff he was relentlessly strict and impeccably fair, entirely unloved but greatly respected. What made him most fearsome was the knowledge that he was incorruptible and unmoved by the prospect of personal monetary gain. His income was relatively modest, his expenses transparent: in the evenings, he and his mousy, ignored wife entertained in high style, as befitted his status, but every sou was accounted for. Bribes left him cold, even when relatives were offering them—favors worth hundreds of thousands of francs were rejected with a shrug. His shortcoming, a fatal one, was his arrogance: he was not an overt bully, and he listened carefully while assessing a situation, but he was right about everything, contemptuous of those who crossed him and dismissive of their arguments. People like him tend not to have friends: friends serve only to make the tough decisions so much harder.

Having established his management style and examined the budget, he hired and fired ruthlessly. Being a shrewd judge of people, he sacked a lot of idle placemen and subsequently remained loyal to those he appointed—several of his closest deputies would remain in their posts even after his own departure. At his right hand was an unprepossessingly disheveled but unflappable architect and surveyor named Eugène Deschamps, who embodied much of Haussmann’s own single-mindedness: he was given the Herculean task of assembling the first-ever comprehensive map of Paris, fully triangulated and on a scale of 1:5,000. This great work, to which Deschamps dedicated himself fanatically, would take three years to complete. Much-smaller versions were produced for public sale, but the original measured 15 square meters (160 square feet). Mounted on a screen behind Haussmann’s desk, it dominated his office. “Many an hour have I spent in fruitful meditation before this altar,” he later recalled.6 Using this as his guide, Haussmann then commanded the leveling of Paris—the elimination of all obstructions, bumps, and dips that would have interfered with his precious straight lines and long vistas. This procedure often required feats of delicate and complex engineering; one early and notable example was the suspension on timber scaffolding of the entire Tour St Jacques, a venerable monument standing on a hillock where the Rue de Rivoli met the Hôtel de Ville: after the ground beneath was flattened, it was lowered back down onto a new base—at the total cost of more than 500,000 francs.7

With such preliminary tasks completed, the greater work could now begin on a scale previously unimagined.

MUCH OF THE FIRST WAVE of development had already been planned and approved by the city authorities when Haussmann took office, so the credit he can take for it is based on what today we would call “project management.” The construction of the elegantly arcaded Rue de Rivoli, started by Napoléon Bonaparte and continued under Charles X and Louis-Philippe, was being extended east; the Louvre was being connected to the Tuileries palace; the covered market at Les Halles was being rebuilt; and Louis Napoléon had his own pet project: the landscaping of the Bois de Boulogne in the English style of Lancelot “Capability” Brown.

However, Haussmann’s immediate priority was to authorize the ruthless elimination of the chaos of crumbling tenements and stables in the Place du Carrousel (now the flat open square of the Louvre Pyramid). As a man who hated mess, he took enormous satisfaction in “clearing all that as my first job in Paris… since my youth the dilapidated state of the Place du Carrousel… seemed to shame France, an admission of impotence on the part of her government, and it stuck in my throat.”8

Looking back, he might have deemed this the least problematic or controversial part of his mission. Much more testing would be the insertion of the first spoke in a vast wheel of wide boulevards designed above all to ease the flow of traffic to and from the railway stations that were fast becoming nineteenth-century Europe’s hubs of trade and human passage. In a project that became known as la grande croisée (the great crossroads), Napoléon Bonaparte’s extension of the Rue de Rivoli would be continued down the Rue Saint Antoine alongside the Marais toward the Place de la Bastille, traversing the reconceived Place du Châtelet at right angles to an entirely new boulevard, running north to south from the Gare du Nord and Gare de l’Est across the Île de la Cité and the Seine down through Montparnasse to the Porte d’Orléans—broadly speaking, the stretch now covered by the Boulevards de Strasbourg, Sébastopol, and Saint-Michel.

From the start, not everyone could see the need for this—why couldn’t the extant and parallel Rue Saint-Denis simply be widened? But cutting corners and making small economies or compromises with minor objections were not in Haussmann’s temperament, and he forged ahead. The first section of this grand thoroughfare would be inaugurated in 1858 with a terrific parade of tarantara typical of the Second Empire. At its intersection with the Place du Châtelet hung gold lamé curtains, suspended between 60-meter (200-foot) minarets and decorated with stars, diamonds, and imperial insignia, that were theatrically drawn up to the sound of trumpets as Louis Napoléon trotted down the route on horseback.9

Haussmann’s passion for road building remained the core of his mission—not until Hitler’s Autobahn program in 1930s Germany would anyone show comparably ambitious determination to improve the passage of traffic. Others, such as Rambuteau, had recognized the problem of Paris’s sclerotic arteries but had balked at the challenge of doing more to unblock them: what was stunningly new about Haussmann’s and Louis Napoléon’s approach was its steamrolling progress through the thickets of physical obstacles and political opposition, as well as its holistic vision of a city with interlinking roads, railway stations, and property development in a massive strategy of social engineering.

Enshrined indelibly in legend is the idea that Louis Napoléon’s secret agenda in extending the boulevards related to security. Like all such myths, it contains a grain of truth. Garrisons and barracks were located at key points along the boulevards, allowing cavalry to advance unimpeded and infantry to march in wide formation in the event of insurrection. Old Paris did indeed contain many uncharted places in which the disaffected or criminal could hide and plot, while broad streets, mapped, numbered, and brightly lit as public spaces, could not be swiftly barricaded with the ease that had allowed the revolutionaries of 1830 and 1848 to bring the city to a halt. But perhaps this was so obvious to everyone that it scarcely needed articulating, and it certainly was not a primary motivation of either Louis Napoléon or Haussmann; it would be more accurate to say that an ideology of efficiency was the impulse, making Paris a smoothly functioning machine that could be controlled and surveyed, generating the maximum of profit for a contented affluent citizenry controlled by a ruling élite.

Haussmann had an almost pathological hatred of blockage—one can detect in him symptoms of an obsessive-compulsive disorder—but his determination to clear human and vehicular circulation was also part of a broader economic strategy that envisaged the boulevards being lined with new retail and residential developments that would yield high levels of rent for entrepreneurs as well as increase employment and tax revenues for the city and state. The complex financial scaffold supporting this construction is a subject to which we shall return.

Despite the initial carping, la grande croisée, executed with stupendous efficiency and completed by 1859, was widely welcomed. Everyone’s legs appreciated the long, clean, straight, smooth thoroughfares, with their generously broad tree-lined pavements; everyone’s eyes enjoyed the artfully calibrated perspectives, interrupted at key points by open squares or circuses and monumental columns or domes; everyone’s lungs benefited from the gutting, draining, and aerating of some of Paris’s most noxious and dilapidated backstreets, home to cholera and crime. But the second phase of Haussmann’s plan would prove more ambitious, expensive, and controversial.10

Through the 1860s, he developed a further 26 kilometers (16 miles) of boulevard. On the Right Bank this included the approaches to the Gare du Nord and Gare Saint-Lazare; the replacement of the slum known as La petite Pologne (Little Poland) with the Boulevard Malesherbes; and the creation of what is now called the Place de la République, fashioned out of a popular chaotic street full of low-grade theaters, dives, and vices known as the Boulevard du Crime (splendidly reimagined in Marcel Carné’s 1945 film Les Enfants du Paradis), with three new avenues leading off it. Perhaps most magnificent was the frame provided for Napoléon Bonaparte’s Arc de Triomphe, the focal point of the Place de l’Étoile, now flanked by twelve ascending satellite streets, crowned by a diadem of fine buildings of uniform scale and design fronted by identical patches of lawn and iron fences—“this lovely arrangement” Haussmann called it, stirred and satisfied by its neat symmetry and grandeur.

On the Left Bank, the Boulevard Saint-Germain was extended and the area around the Panthéon radically altered. But it was the Île de la Cité, sitting in the middle of the Seine, that underwent the most comprehensive reinvention. This was Haussmann’s idea of hell—“a place choked by a mass of shacks,” he wrote, “inhabited by bad characters and crisscrossed by damp, twisted and filthy streets”—and he attacked it vigorously. New bridges, the Pont Saint-Michel and Pont au Change, were constructed; the Hôtel-Dieu hospital and orphanage were rebuilt; there was massive clearance of the shambles that enshrouded Nôtre-Dame; and thousands of defenseless working people were expelled to make room for two imposingly expansive government buildings, the Tribunal de Commerce and the Prefecture de Police. At least Haussmann stopped short of demolishing the thirteenth-century Sainte-Chapelle, a Gothic masterpiece that constituted the last remains of the palace of the Capetian dynasty, and the gruesomely picturesque turreted prison of the Conciergerie, where Marie Antoinette, Charlotte Corday, and Robespierre were incarcerated before their executions. Yet what had been a place of messy human communities was eerily left as little more than a lifeless theme park showcasing authoritarian institutions. It has been suggested that Haussmann’s vendetta was motivated by an element of personal neurosis: as a sickly asthmatic child repelled by dirt and terrified of foul air, he had traumatically been obliged to cross the Île from his home to school every morning.11

IN 1860, FOLLOWING A DECISION only perfunctorily debated by consultative bodies and all too typical of his autocracy, Louis Napoléon demolished the inner Fermiers-Generaux wall12 round the center and brought the suburbs of Paris directly under the administration and surveillance of the city. Eleven villages and townships outside the old wall were affected by this decree,13 bringing the number of arrondissements from twelve to twenty, at which it remains today. Overnight this appropriation doubled the acreage of the city and increased its population by a third. In accordance with the nineteenth-century belief in the virtues of free trade, the tolls and taxes that farmers had to pay to bring their produce through the gates of the Fermiers-Generaux into the center were thereby abolished, and Haussmann assumed responsibility for areas of heavy toxic industry, small agricultural backwaters, and virtually lawless stretches of scrub, neither rural nor urban, largely inhabited by impoverished, undocumented vagrants holed up in miserable shacks and sustained by petty crime and cheap alcohol.

Demolitions and excavations on the Île de la Cité, creating a square that allowed a full view of the facade of Nôtre-Dame for the first time. (ROGER VIOLLET / GETTY IMAGES)

Obliged to trudge daily miles to and from work in the center, much of this population eked out a wretched living on Haussmann’s building sites. Some had been forcibly evacuated from the slums on the Île de la Cité; others came penniless from the countryside in search of employment. Few of the latter expressed any particular wish to be Parisian, and there was a certain resistance to the official attention and regulation that their new civic status entailed. The happiness of souls or the condition of morals was not something that concerned the unremittingly practical Haussmann, but furnishing this no-man’s-land with basic social amenities such as cobbled roads, sewage disposal, street lighting, and water supply became his Herculean task. In the short term, the expense of the operation was a major drain on the city’s financial resources; in the longer term, it would prove as transformational as anything else he achieved, shaping and civilizing areas now as organic to Paris as Auteuil, Batignolles, and Bercy.14

The problem to which neither he nor Louis Napoléon paid sufficient attention was housing the inhabitants of these outlying regions, and this would prove to be their biggest mistake at the levels of both basic humanity and political calculation (a mistake that many Western states are continuing to make in our own era). The majority of migrant families lived in the sort of hovels or shacks we would nowadays associate with the poorest parts of India: shelters cobbled together from wooden planks, sheets of corrugated iron, and anything else that could be foraged from dustheaps. Single men, if they were lucky, would be accommodated and fed in rough dormitories or vermin-ridden attics owned by the builders for whom they worked and to whom they would have to pay substantial rent.

At the time there was virtually no concept anywhere in Europe of direct state control over the provision of what we would now call social housing. This was a matter for individual enterprise, Haussmann believed: let the market provide what the market wants, which in this case, as so often, resulted in a glut of high-end, high-rent housing along the new boulevards, umbilically linked in economic terms to abutting shops and businesses and accessible only to those who could raise a mortgage. One fault line at the heart of this has been forcefully summed up by urban scholar Anthony Sutcliffe:

Haussmann had hoped that if the right conditions were created for building, free enterprise could provide sufficient accommodation for the very poor, and allow rents to stabilize. But by driving new streets through the centre, he did the opposite. Although he pointed out that the new buildings contained more dwellings than those that the City was demolishing, he conveniently ignored the fact that much of the land was not available for building after improvement, because it was incorporated in streets or open spaces. He also forgot that the older buildings were often let and sub-let room by room, whereas the new houses in the centre were divided into relatively spacious apartments and were, in any case, rarely occupied by the working classes.15

Louis Napoléon knew that there was a problem here, and he worried that a working class doomed to sordid living conditions could become politically disruptive. He favored a slightly more interventionist line, taking a benevolent if ineffectual interest in several schemes for cités ouvrières (workers’ estates), inspired by the paternalistic socialism of Claude Saint-Simon, an early-nineteenth-century philanthropic thinker whose meritocratic ideas greatly appealed to him. But sufficient capital for these well-intentioned projects could never be raised, leaving ateliers de charité, run on workhouse lines by the church and restrictively governed by curfews and regulations, as the last resort of the destitute and the desperate.

THE GREAT BULK OF HOUSING built during the Second Empire was squarely destined for the accommodation of the middle class. What financed it was a banking boom, at the head of which were two Sephardic Jews of Portuguese origin, the brothers Emile and Isaac Péreire. Bitterly controversial figures, they have been called many things—astute venture capitalists, brilliant visionary speculators, ruthless profiteers—according to the ideological position of the observer. Beyond question they were the aggressive new presence in the Bourse, promoting through their chief creation, the Crédit mobilier, a concept of banking that was more open, daring, and wolfish than that of the more-refined, longer-established, and prudent Rothschilds. They took risks on innovation and enterprise, gambling heavily on all the growth areas of the mid-nineteenth century—railways, cabs and omnibuses, hotels, mining, insurance, gas, transatlantic shipping, and newspapers, as well as a loan to the government for the Crimean campaign of 1853–1856. Much of the time their daring paid off, buoyed by some highly creative accounting, gold rush money from America and Australia, and a generally optimistic economic climate.

Extending large-scale credit and allowing artisans and petits bourgeois to invest small amounts of their savings, the Péreires pumped money through Second Empire France and became the lifeblood of Haussmann’s project. The government was only too happy to relax some restrictive regulations in Crédit mobilier’s favor—taxation alone could never pay for its scale of ambition—and various wings and subsidiaries of the Péreires’ empire took on direct responsibility for vast retail and housing developments. They were particularly prescient—some said, suspiciously so—in buying up undervalued land and building hotels around what would become the site of the new Opéra. For fifteen years they walked a tightrope until the economic slowdown in 1867 revealed the extent of their leverage and brought about a sharp crash. By that time, Haussmann had moved on, and, as we shall see, a lack of transparency in his hunt for capital would prove his downfall.16

Meanwhile, there were fortunes to be made in a system with plenty of room for the venal and unscrupulous standing in the path of progress to benefit from graft, corruption, and scams. Speculators second-guessed the routes of new roads and at bargain prices bought up land or freeholds that would double in value once their redevelopment was announced. Leaks of information from Haussmann’s office in the Hôtel de Ville could not be plugged, even though the hands of Haussmann and his top echelon appear to have remained perfectly clean. Compulsory purchase orders also provided ordinary Parisians with a game that was easy to play, with a good chance of rich winnings. The rules were simple: you only had to be one step ahead. At the moment that an eviction notice was served on your property, you called in a crooked broker skilled in the dark art of making your premises look to the surveyors much better than the property did five minutes before it was condemned, either by importing some borrowed smart furniture to prettify a salon or cooking the accounts to suggest a booming trade. The broker would then skim off a percentage of the compensation, assessed by public juries all too ready to take bribes themselves in return for a favorable decision. Such practices contributed to an embarrassing overage of hundreds of millions of francs past the original budgets. In other respects they quelled opposition and made the job easier: Haussmann’s schemes could be regarded as operating in many Parisians’ narrow self-interest and short-term gain.17

IF THE NAME OF HAUSSMANN means anything to the wider public today, it evokes the uniform rows of five- or six-story apartment blocks that run along the boulevards and avenues of central Paris. Much imitated all over Europe, they have become one of the archetypes of high-density urban domesticity, as resilient and flexible as the terrace villas that line London’s Victorian suburbs. The middle classes like living in them; over two centuries they have weathered hardily and still do the job.

Many people must think that Haussmann designed the architectural template himself, but that is not the case. In fact, no single person can take the credit. One of the virtues of these buildings is that they are not highly or individually designed so much as evolved out of what was already there—the simple model being that of a shop or atelier on the ground floor, with flats of various proportions ascending over several levels to attics for servants and storerooms. In the Paris of the early nineteenth century, their frontage was typically narrow, perhaps 6 or 7 meters (20–23 feet) across, but the accommodation they offered could extend up to 40 meters (130 feet) deep; a long-standing citywide regulation limited overall heights relative to street widths. Haussmann liberalized these dimensions in his boulevards, enabling a more general improvement in the circulation of air, traffic, and population.18 A cramped and miscellaneous city was becoming a spacious and coherent one.

The Rue de Rivoli, a project started under Napoléon Bonaparte and completed under Louis Napoléon—its clean, straight uniformity, smoothly running traffic, and pleasantly airy trees and parks all being aspects of Haussmann’s ideal city. (L.P. PHOT FOR ALINARI / ALINARI VIA GETTY IMAGES)

The broad lines of the “Haussmann style” were established in the 1840s, and only the professional eye can distinguish blocks erected during the last years of Louis-Philippe’s reign from those of the early Second Empire (the Rue Rambuteau, for example, was built in the late 1830s). Haussmann had good if unadventurous taste, took an intelligent interest in new industrial technologies, and insisted on rigorous construction practices: he would not cut corners to save a few short-term francs, and everything commissioned during this era was built to last. Refining the aesthetic code for the new regime appears to have been the responsibility of an architect named Gabriel Davioud, working out of Haussmann’s office and also responsible for the design of much of the street furniture that graced the boulevards and parks, including the bandstands and ironwork.

Frustratingly, we do not know enough about the extent to which specifics were made compulsory because so much of the relevant documentation was destroyed by the fire that gutted the Hôtel de Ville in 1871. Nevertheless, what is clear from the surviving evidence is that the widespread notion that Haussmann’s blocks are all the same is a delusion; whatever guidelines were set in the interests of an overall compositional unity, some room for difference and ornament remained. As architectural historian François Loyer put it, “Second Empire architecture has been criticized for the poverty of its mass effects and boring uniformity created by buildings of identical size, which is to overlook the fact that the monotony of the general forms was compensated for by an extraordinary variety of visual detail,” most readily visible today in the decoration of window frames, lintels, corbels, and ironwork.19

The geometric principle underlying the new boulevards was a certain breadth in proportion to the regularized height of the buildings; in most cases, parallel lines of fast-growing plane trees were planted to provide enriching contrast with the grayness of the stone facades, cobbled roads, pavements, and curbs. Dressed and polished limestone from the quarries of the Oise region north of Paris, now conveniently transported as freight on the railways, became the standard building material (and regulations enforcing its decennial cleaning and maintenance have always been rigidly enforced on pain of a large fine). Roofs, slanting or curved, beneath which lodged the servant class in garrets or chambres de bonne, were traditionally made of zinc or slate; guttering was dark brown; and there could be no deviation from the sizes of windows that ran at fixed intervals across each floor of each block. But as a stroll along the Boulevard Saint-Michel can still demonstrate, richly nuanced differentiation in the shape of porticos, the ornament of their lintels and pediments, the modeling of pillars and caryatids, the framing of windows, and the patterns of balcony ironwork could happily be accommodated.

What is regrettable is that during the late 1860s, as the lion of capital ran rampant and roared ever louder, property developers became increasingly adept at bending and stretching the rules, building faster and cheaper with less attention to these decorative individualities. The result was a more stolid and unimaginative interpretation of the classical principles, marked by cruder carving and larger expanses of bare wall—this is particularly the case in outlying districts such as Ménilmontant, where overall coherence was less of an issue.

Behind the facades, what is most noticeable about the “typical” Haussmann apartment building (although it has been argued that there is no such thing) is a separation of class, status, and function much more rigidly hierarchical than had previously been usual. The shop on the ground floor no longer connected with the entrance hall to the residential levels; the common parts of stairwells and landings became progressively less grandiose and expansive as they ascended to the smaller flats on the upper floors; servants and trade came and went as surreptitiously as possible through a narrow back stairwell. Inside the apartments, the old idea of an enfilade of rooms, each of which might be used for sitting, eating, sleeping, and washing (or a combination of these), was replaced by a more defined pattern, partly dictated by the expansion of indoor plumbing and the water supply. Privacy, hygiene, and comfort were priorities: the pillars of the bourgeois lifestyle.20