The sun falls timidly against our backs as we walk through La Quiaca’s bare hills.1 I turn recent events over in my mind. The departure, with so many people, quite a few tears, and the peculiar looks from those in second class at the profusion of fine clothes, leather coats, etc. of those who came out to farewell two strange-looking snobs2 loaded down with so much luggage. The name of my sidekick has changed—Alberto is now Calica3 — but the journey is the same: two distinct wills extending out into the Americas, not knowing exactly what it is they seek, nor in which direction it lies.

The sparse hills, covered with a gray mist, lend color and tone to the landscape. A small stream in front of us separates Argentina from Bolivian territory. Across a miniature railway bridge, two flags face each other: the Bolivian, new and brightly colored; the other old, dirty and faded, as though it had begun to grasp the poverty of its symbolism.

A couple of policemen tell us that someone from Alta Gracia, Córdoba (my hometown as a child), is working with them. This turns out to be Tiqui Vidora, one of my childhood playmates. A strange rediscovery in this far corner of Argentina.

An unrelenting headache and asthma force me to slow down, and we spend three particularly boring days in the village there before departing for La Paz. Mentioning that we are traveling second class elicits an instantaneous loss of interest in us. But here, like anywhere else, the possibility we might provide a good tip ensures a certain level of attention.

In Bolivia now and, after a cursory inspection from both Argentine and Chilean customs, there have been no further delays.

From Villazón, the train struggles north through totally arid hills, ravines and trails. The color green is proscribed here. The train recovers its appetite on the dry pampas, where saltpeter becomes more common. But when the night arrives, everything is lost in a cold that creeps in so slowly. We have a cabin now, but in spite of everything—including extra blankets—a vague chill enters our bones.

The next morning our boots are frozen and our feet hurt. The water in the toilets and even in our flasks has frozen. Unkempt and with dirty faces, we feel slightly anxious as we make our way to the dining car, but the faces of our traveling companions put us at ease.

At 4 in the afternoon, the train approaches the gorge in which La Paz nestles. A small and very beautiful city spreads through the valley’s rugged terrain, with the eternally snowcapped figure of Illimani watching over it. The final few kilometers take over an hour to complete. The train seems fixed on a tangent to avoid the city, but then it turns and continues its descent.

It’s a Saturday afternoon and the people we have been recommended to see are hard to find, so we spend the time changing our clothes and ridding ourselves of the journey’s grime.

We begin Sunday by going to see the people who have been recommended to us and making contact with the Argentine community.

La Paz is the Shanghai of the Americas. Many adventurers and a marvelous range of nationalities have come here to stagnate or thrive in this polychromatic, mestiza city that determines the destiny of this country.

The so-called fine folk, the cultured people, have been surprised by events and curse the attention now being paid to the Indian and the mestizo, but I divined in all of them a faint spark of nationalist enthusiasm with regard to some of the government’s actions.4

Nobody denies that the situation represented by the power of the three tin mine giants had to come to an end, and young people believe that this has been a step forward in the struggle for greater equality between the people and the wealthy.

On the evening of July 15, there was a long and boring torchlight procession—a kind of demonstration—although it was interesting because of the way people expressed their support by firing shots from Mausers, or Piri-pipi, the terrible repeating guns.

The next day there was a never-ending parade of workers’ guilds, schools and unions, with the regular song of Mausers. Every few steps, one of the leaders of the companies into which the procession was divided would shout, “Compañeros of such-and-such-a-guild, long live Bolivia! Glory be to the early martyrs of our independence, Glory to Pedro Domingo Murillo, Glory to Guzmán!, Glory to Villarroel!”5 This recitative was delivered wearily, and accordingly a chorus of monotonous voices responded. It was a picturesque demonstration, but not particularly vital. Their weary gait and general lack of enthusiasm drained it of any vitality, while, according to those in the know, the energetic faces of the miners were missing.

On another morning we took a truck to Las Yungas. Initially, we climbed 4,600 meters to a place called the Summit, and then came down slowly along a cliff road flanked almost the entire way by a vertical precipice. We spent two magnificent days in Las Yungas, but we could have done with two women to provide the eroticism missing from the greenery that assaulted us everywhere we looked. On the lush mountain slopes, which plunged several hundred meters to the river below and were protected by an overcast sky, were scatterings of coconut palms with their ringed trunks; banana trees that, from the distance, looked like green propellers rising from the jungle; orange and other citrus trees; coffee trees, rosy red with their beans, and other fruit and tropical trees. All this was offset by the spindly form of the papaya tree, its static shape somehow reminiscent of a llama, or of other tropical fruit trees.

On one patch of land, Salesian priests were running a farm school. One of them, a courteous German, showed us around. A huge quantity of fruit and vegetables were being cultivated and tended very carefully. We didn’t see the children, who were in class, but when he spoke of similar farms in Argentina and Peru I remembered the indignant remark of a teacher I knew: “As a Mexican educationalist said, these are the only places in the world where animals are treated better than people.” So I said nothing in reply. For white people, especially Europeans, the Indian continues to be an animal, whatever habit they happen to be wearing.

We made the return journey in the small truck of some guys who had spent the weekend in the same hotel. We reached La Paz looking rather strange, but it was a quick and reasonably comfortable trip.

La Paz, ingenuous and candid like a young girl from the provinces, proudly displays her marvelous public buildings. We checked out the new constructions, the diminutive university overlooking the entire city from its courtyards, the municipal library, etc.

The formidable beauty of Mt. Illimani radiates a soft light, perpetually illuminated by the halo of snow which nature has lent it for eternity. When twilight falls, the solitary mountain peak becomes most solemn and imposing.

There’s a hidalgo from Tucumán here who reminds me of the mountain’s august serenity.6 Exiled from Argentina, he is the center and the driving force of the Argentine community in La Paz, which sees in him a leader and a friend. To the rest of the world, his political ideas are well and truly outdated, but somehow he keeps them independent of the proletarian hurricane that has been broken loose across our bellicose sphere. He extends his friendly hand to all Argentines, without asking who they are or why they’ve come. He casts his august serenity over us, miserable mortals, extending his patriarchal, lasting protection.

We remain stranded, waiting for something to turn up, waiting to see what happens on the 2nd. But something sinuous and big bellied has crossed my path. We’ll see…

At last we visited the Bolsa Negra mine. We took the road south up to a height of some 5,000 meters before descending into the depths of the valley where the mine administration is located, the seam itself being on one of the slopes.

It’s an imposing sight. Behind us, the august Illimani, serene and majestic; in front of us, the white Mururata; and closer, the mine buildings that look like fragments of glass tossed off the mountain and remaining there at the fanciful whim of the terrain. A vast spectrum of dark tones illuminates the mountain. The silence of the idle mine assaults those who, like us, do not understand its language.

Our reception was cordial; they gave us lodging and then we slept. The next morning, a Sunday, one of the engineers took us to a natural lake fed by one of Mururata’s glaciers. In the afternoon we visited the mill where tungsten is refined from the ore produced in the mine.

Briefly, the process is as follows. The rock extracted from the mine is divided into three categories: the first has a 70 percent extractable deposit; another part has some wolfram, but in lesser quantity; and a third layer, which you could say has no value, is tipped onto the slopes. The second category goes to the mill on a wire rail or cableway, as they call it in Bolivia; there it is tipped out and pounded into smaller pieces, after which another mill refines it further, before it is passed through water several times to separate out the metal as a fine dust.

The director of the mill, a very competent Sr. Tenza, has planned a number of reforms that should result in increased production and the better exploitation of the mineral.

The next day we visited the excavated gallery. Carrying the waterproof bags we’d been given, a carbide lamp and a pair of rubber boots, we entered the black and unsettling atmosphere of the mine. We spent two or three hours checking buffers, noting the seams that disappear into the depths of the mountain, climbing through narrow openings to different levels, feeling the racket of the cargo being thrown onto wagons and sent down for collection on another level, watching the pneumatic drills prepare holes for the load.

But the mine’s heart was not beating. It lacked the energy of the arms of those who every day tear from the earth their load of ore, arms that on this day, August 2, the Day of the Indian and of Agrarian Reform, were in La Paz defending the revolution.7

The miners arrived back in the evening, stone-faced and wearing colored plastic helmets that made them look like warriors from foreign lands. We were captivated by their impassive faces, the unwavering sound of unloading material echoing off the mountain and the valley that dwarfed the truck carrying them.

In present conditions, Bolsa Negra can go on producing for five more years. But its production will cease unless a gallery some thousands of meters long can be linked with the seam. Such a gallery is being planned. These days this is the only thing that keeps Bolivia going, and it’s a mineral the Americans want; so the government has ordered an increase in production. A 30 percent increase has already been achieved thanks to the intelligence and tenacity of the engineers in charge.

The amiable Dr. Revilla very kindly invited us to his home. We set off at 4:00, taking advantage of a truck. We spent the night in a small town called Palca, and arrived in La Paz early.

Now we are waiting for an [illegible] in order to be on our way.

Gustavo Torlincheri is a great photographic artist. Apart from a public exhibition and some work in his private collection, we had an opportunity to see him at work. His simple technique supports a more important, methodical composition, resulting in remarkably good photos. We joined him on an Andean Club trip from La Paz that went to Chacaltaya and then the water sources of the electricity company that supplies La Paz.

Another day I visited the Ministry of Peasant Affairs, where they treated me with extreme politeness. It’s a strange place where masses of Indians from different highland groups wait their turn for an audience. Each group has a unique costume and a leader—or indoctrinator—who addresses them in their particular language. Employees spray them with DDT as they enter.

Finally, everything was ready for us to leave; each of us had a romantic contact to leave behind. My farewell was more on an intellectual level, without too much sentiment, but I think there is something between us, she and I.

The last evening saw toasts at Nougués’s house—so many that I left my camera there. In all the confusion, Calica left for Copacabana alone, while I stayed another day, using it to sleep and to retrieve my camera.

After a very beautiful journey beside the lake, I scrounged my way to Tiquina and then made it to Copacabana. We stayed in the best hotel and the following day hired a boat to take us to Isla del Sol.

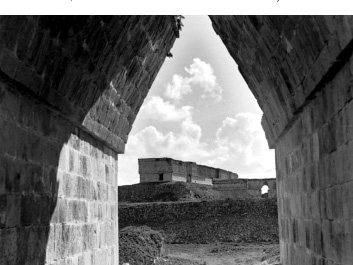

They woke us at 5 a.m. and we set off for the island. There was very little wind so we had to do some rowing. We reached the island at 11 a.m. and visited an Inca site. I heard about some more ruins, so we urged the boatman to take us there. It was interesting, especially scratching around in the ruins where we found some relics, including an idol representing a woman who pretty much fulfilled all my dreams. The boatman didn’t seem eager to return, but we convinced him to set sail. He made a complete hash of it, however, and we had to spend the night in a miserable little hut with straw for mattresses.

We rowed back the next morning, working like mules against the exhaustion that overcame us. We lost the day sleeping and resting, and resolved to leave the following morning by donkey; we then had second thoughts and decided to postpone our departure until the afternoon. I booked a ride on a truck, but it left before we arrived with our bags, leaving us stranded until we finally managed to get a ride in a van. Then our odyssey began: a two-kilometer walk carting hefty bags. Eventually we found ourselves two porters and amid laughter and cursing we reached our lodgings. One of the Indians, whom we nicknamed Túpac Amaru, was an unhappy sight: Each time he sat down to rest we had to help him back to his feet, as he could not stand up alone. We slept like logs.

The next day we met with the unpleasant surprise that the policeman was not in his office, so we watched the trucks leave, unable to do a thing. The day passed in total boredom.

The next day, comfortably installed in a “couchette,” we traveled beside the lake toward Puno.8 Nearby, some tolora blossoms were flowering—we hadn’t seen any since Tiquina. At Puno we passed through the last customs post, where I had two books confiscated: Men and Women in the Soviet Union, and a Ministry of Peasant Affairs publication, which they loudly proclaimed as “red, red, red.” After some banter with the chief of police I agreed to look for a copy for him in Lima. We slept in a little hotel near the railway station.

We were about to climb into a second-class carriage with all our gear when a policeman proposed (with an air of intrigue) that we could travel free to Cuzco in first class using two of their badges. So, of course, we agreed. We therefore had a very comfortable ride, paying them the cost of our second-class tickets. That night, arriving at the station in Cuzco, one of them disappeared without his badge, leaving it in my possession. We stayed in a small dump of a hotel and had a good night’s sleep.

The next day we went to lodge our passports and stumbled across a secret policeman who asked (in that professional tone they have) where the badge was that I had been given the night before. I explained what had happened and handed back the badge. The rest of the day we spent visiting churches, and the next day as well. We have now seen Cuzco’s most important sights, if a little superficially, and are waiting for an Argentine lady to change some of our money into sols so we can go to Machu-Picchu as soon as possible.

Now we have our sols, but for 1,000 pesos they’ve only given us 600. I don’t know how much this was due to the Argentine woman, because the intermediary did not appear. Anyway, for the moment at least, we are safe from hunger.

Cuzco, 22 [August 1953]

Pay attention here, mami.

This second trip has been most enjoyable, and I almost feel like a rich man, but the impact is different. Where Alberto entertained me with talk about marrying Inca princesses and restoring empires, Calica curses the filth and every time he steps on one of the innumerable [human] turds that line the streets, he looks at his dirty shoes instead of the sky or the silhouette of some cathedral. He does not smell the intangible, evocative things about Cuzco, but only the stink of stew and shit. It’s a matter of temperament. All this apparent incoherence—I’m going, I went, I didn’t go, etc.—was because we needed them to believe we had left Bolivia. A revolt was expected at any moment and we had the solemn intention to stay and see what happened close up. To our disappointment, nothing eventuated; all we saw were shows of strength from the government which, contrary to everything that is said, seems to me to be fairly secure.

I was thinking of getting work in a mine, but didn’t want to stay more than a month; they offered me a minimum of three so I didn’t stick to that plan.

Afterward we went to the shores of Lake Titicaca, or Copacabana, and spent a day on the Isla del Sol, the famous sanctuary of Inca times where I achieved one of my most cherished ambitions as an explorer: I found a little statue of a woman in an indigenous burial ground, the size of a little finger but an idol all the same, made of the famous chompi, the alloy used by the Incas.

On reaching the border, we had to walk two kilometers without transport; and for one kilometer it fell to me to carry my suitcase filled with books, which nearly broke my back. The two of us and the two laborers had our tongues on the ground by the time we arrived.

At Puno I had a hell of a fight with customs, because they took a Bolivian book from me, claiming it was “red.” There was no persuading them that these were scientific publications.

Of my future life I can tell you nothing, because I know nothing, not even how things will go in Venezuela. But we have now got the visa through an intermediary […]. As to the more distant future, I can say I haven’t changed my mind about the US$10,000, and that I may do another trip through Latin America, only this time in a North-South direction with Alberto, and this might be by helicopter. Then Europe and then who knows. […]

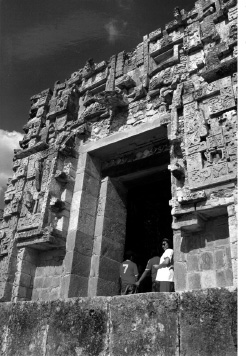

In these days of waiting we have exhausted Cuzco’s supply of churches and interesting monuments. Again my head is full of a motet of altars, large paintings and pulpits. The simple serenity of the pulpit in the Church of San Francisco was impressive, its sobriety contrasting with the grandiosity of nearly all the colonial buildings here.

Belén certainly has nice towers, but the brilliant white of the two bell towers here is stunning, set off by the dark colors of the old nave.

My little Inca statue—her new name is Martha—is authentic, and made of tunyana, the Incan alloy. One of the museum staff confirmed this. It’s a pity the vessel fragments seem bizarre to us, considering they represent that former civilization. We have been eating better since the payment.

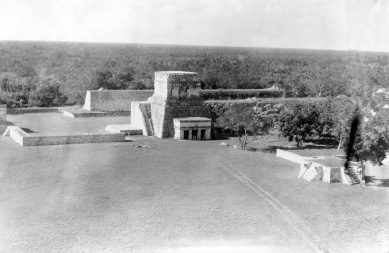

Machu-Picchu does not disappoint; I don’t know how many times I can go on admiring it. Those gray clouds and purple-colored peaks, against which the gray ruins stand out, are one of the most marvelous sights I can imagine.

Don Soto received us very well and then only charged us half the cost of our accommodation. But despite Calica’s enthusiasm for this place, I’m forever missing Alberto’s company. Especially here in Machu-Picchu, I’m always remembering how well our characters complemented each other.

We’re back in Cuzco to take a look at a church and wait for a truck to leave. One by one our hopes are dismantled, as the days pass and the pesos and sols dwindle. We had already found a truck, just what we needed, when, with all the bags loaded, there was a huge row over two pounds in weight we honestly did not have. If we had been willing to compromise, we might have come to a deal, but as it was we were stranded until the next day, Saturday. Our first calculation suggests it would have cost us 40 sols more than the bus.

Here in Cuzco we met a spirit medium. It happened like this: In a conversation with the Argentine woman and Pacheco, the Peruvian engineer, the talk turned to spiritualism. We had to suppress our laughter, putting on serious faces, and the next day they took us to meet him. The guy pronounced he could see some strange lights within us—the green light of sympathy and that of egoism in Calica, and the dark green of adaptability within me. He then asked me if something was wrong with my stomach, as my radiations were fading, which left me thinking as my stomach was definitely churning from the Peruvian peas and all the tinned food. A pity I wasn’t able to have a proper session with him.

Now we have left Cuzco behind us and after an endless three-day bus journey we reached Lima. For the entire trip from Abancoy, the road followed the ever-narrowing ravine of the Apurimac river. We washed in a small pool barely deep enough to cover us, and the cold was so intense that for me it was no fun.

The journey became interminable. The chickens shat all over the place beneath our seats, and the smell of duck was so unbearably thick you could cut it with a knife. A few punctures dragged the journey out even further, and when we finally reached Lima we slept like logs in a small dive of a hotel.

On the bus we met a French explorer who had been sailing on the Apurimac River when his boat sunk and the current took his companion. At first he said she was a teacher, but it turned out she was a student, running away from her parents’ home, and that she didn’t know how to swim. The guy is going to face a few troubles ahead.

I went to visit Dr. Pesce and the people from the leprosy colony.9 Everyone greeted me most cordially.

Nine days have passed in Lima, although due to various engage ments with friends we still haven’t seen anything extra special. We found a university diner that charges 1.30 a meal, which suits us perfectly.

Zoraida Boluarte invited us to her place, and from there we went to the famous 3-D cinema. It doesn’t seem all that revolutionary to me and the films are just the same. The real fun came later, when we found ourselves with two cops who turned the place upside down and carted us down to the police station. After a few hours there, we were released and told to come back the next day— today. We’ll see.

The police stuff came to nothing: After a mild interrogation and a few apologies, they let us go. The next day they called us back in with some questions about a couple who had kidnapped a boy. They bore some resemblance to the Roy couple in La Paz.

The days succeed each other with nothing new and no opportunities. The only event of any import has been our change of residence, which enables us to live totally gratis.

The new house has worked out magnificently. We were invited to a party, and although I couldn’t drink because of my asthma, Calica used the opportunity to get smashed once again.

Dr. Pesce honored us with one of his rambling, genial chats in which he touches with such assurance on so many diverse topics.

Our tickets for Tumbes are almost a sure thing—they’re being arranged by a brother of Sra. de Peirano. So here we are, waiting, with practically nothing more to see in Lima.

Empty days continue to go by, and our own inertia ensures we remain in this city longer than we had hoped. Perhaps the ticket question will be resolved tomorrow, Monday, so we can set a definite departure date. The Pasos have made an appearance, saying they have good work prospects here.

We’re almost on our way, with only a few minutes left to look over dreamy Lima again. Its churches are filled with an interior magnificence that doesn’t extend to their exteriors—my opinion— they don’t have the dignified sobriety of Cuzco’s temples. The cathedral has several scenes of the Passion of great artistic worth, which seem like they have been done by a painter from the Dutch school. But I don’t like its nave, or its stylistically amorphous exterior, which looks as if it was built in the transition period when Spain’s martial fury was on the wane and a decadent love of ease and luxury was rising. San Pedro has a number of valuable paintings, but I don’t like its interior either.

We ran into Rojo, who had had the same trouble as us, only more so owing to the particular books he was carrying. He is traveling to Guayaquil, where we will meet up.

To farewell Lima we saw “The Big Concert,” a Russian film dangerously like US cinema, although better, considering its color and musical quality. Saying good-bye to the patients was really quite emotional, I think I will write about it.

Lima, September 3 [1953]

Dear Tita,10

Sadly, I have to write to you in my beautiful handwriting, as I haven’t been able to get hold of a typewriter to remedy the situation. At any rate, I hope you have a day free to dedicate to reading this letter.

Let’s get to the point. Thank your friend Ferreira for the letter of introduction to the Bolivian college. Dr. Molina was very kind to me and seemed enchanted with both me and my traveling companion, the one you met at home. He subsequently offered me a job as a doctor and Calica work as a nurse in a mine; we accepted, but wanted to reduce the three months he wanted us to stay to one. Everything was settled and amicable and we were to report the next day to finalize details. Imagine our surprise when the next day we found out Dr. Molina had left to inspect the mines and wouldn’t be back for two or three days. So we presented ourselves then, and still no Molina, although they believed he would be back in another couple of days. It would take too long to recount the times we went looking for him; the fact is that 20 days passed before he returned, and by then we could no longer agree to a month—the lost time would have made it two—so he gave us some introductory letters for the director of a tungsten mine, where we went for two or three days. Very interesting, especially because the mine is in a magnificent location. Overall the trip was worthwhile.

I should tell you that in La Paz I ignored my diet and all that nonsense, and nevertheless felt wonderful for the month and a half I spent there. We traveled quite a bit into the surrounding area— to Las Yungas, for example, very pretty tropical valleys—but one of the most interesting things we did was to study the intriguing political scene. Bolivia has been a particularly important example for the American continent. We saw exactly where the struggles had taken place, the holes left by bullets and even the remains of a man killed in the revolution and recently discovered in the cornice of a building—the lower part of his body had been blown away by one of those dynamite belts they wear around their waists. In the end, they fought without holding back. The revolutions here are not like those in Buenos Aires—two or three thousand (no one knows for sure how many) were left dead on the battlefield.

Even now the fighting continues, and almost every night people are wounded by gunfire on one side or the other. But the government is supported by an armed people, and there is no possibility of liquidating an armed movement from outside. It can, however, succumb to internal conflicts.

The MNR [Nationalist Revolutionary Movement] is a coalition with three more or less clear tendencies: the right, represented by Siles Suazo, vice-president and hero of the revolution; the center, represented by Paz Estenssoro, shiftier and probably as right-wing as the first; and the left, represented by Lechín, the visible head of a serious protest movement, but who himself is an unknown given to partying and chasing women. Power is likely to remain in the hands of Lechín’s group, which counts on the powerful support of the armed miners, but resistance from their colleagues in government may prove serious, particularly as the army is going to be reorganized.

Well, I’ve told you something about the Bolivian situation. I’ll tell you about Peru later, when I’ve lived here for a little longer, but in general I think that Yankee domination in Peru has not even created the fiction of economic well-being that can be seen in Venezuela, for example.

Of my future life, I know little about where I am headed and even less when. We have been thinking of going to Quito and from there to Bogotá and Caracas, but of the intermediary steps we haven’t got much of an idea. I’ve only recently arrived here in Lima from Cuzco.

I won’t tire of urging you to visit there if possible, especially Machu-Picchu. I promise you won’t regret it.

I guess that since I left you must have taken at least five subjects, and I imagine you still go fishing for worms in the muck heap. There’s little or nothing to write you about vocations, but if one day you change your tune and want to see the world,

remember this friend

who would risk his skin

to help you however he can

when the occasion arises

A hug. Until it occurs to you, and we’re in the same place when it does,

Ernesto

The first leg of the journey got us to Piura without a break, where we arrived at lunchtime. Sick with asthma, I locked myself in my room, and only went out for a while in the evening to see a bit of the town, which is like a typical Argentine provincial city, but with more new cars.

Convincing the driver that we should pay less, the next day we took the bus to Tumbes and got there as night was falling. Among other towns, the journey took us through Talara, a rather picturesque oil port.

I didn’t get to see Tumbes either because of asthma, and we continued our journey to the border at Aguas Verdes, crossing over to Huaquillas,11 but not without suffering at the hands of the gangs who organize transport from one side of the bridge to the other. A lost day in terms of travel, which Calica used to scrounge a few beers.

The next day we set out for Santa Marta, where a boat took us on the river as far as Puerto Bolívar, and after an all-night crossing we arrived the next morning in Guayaquil, me, still with asthma.

There we met “Fatty” Rojo, no longer alone but with three friends from law school, who took us to their boarding house.12

We were six in total and with our last rounds of mate we formed a tight student circle. The consul was unreceptive when we tried to hit him for some mate leaves.

Guayaquil, like all these ports, is an excuse for a city that barely has its own life. It revolves around the daily succession of ships arriving and departing.

I wasn’t able to see much, because the guys leaving for Guatemala told travelers’ tales that were far too absorbing; one of them included Fatty Rojo. Later, I met a young guy, Maldonado,13 who introduced me to some medical people, including Dr. Safadi,14 a psychiatrist and a “bolshie” [Bolshevik] like his friend Maldonado. They put me in touch with another leprosy specialist.

They have a closed colony with 13 people in fairly bad condition, for whom there is little specific treatment.

At least the hospitals are clean and not all that bad.

My favorite way to pass the time is playing chess with people at the boarding house. My asthma is a bit better. We’re thinking of staying for a couple more days, and trying to track down Velasco Ibarra.15

Plans made and unmade, financial worries and Guayaquilian phobias, all the result of a passing joke García made saying, “Hey, guys, why don’t you come with us to Guatemala?”16 The idea had already been in my head, waiting only for this prompt. Calica followed. These are now days of a feverish search. We’ve almost certainly been granted the visas, but for an estimated $200. The shortfall of $120.80 will be hard to find but we hope to do it with some luck and by trying to sell our stuff. The trip to Panama will be free, apart from $2 each a day, making it $32 for the four of us. This is all we have talked about, although, we can always cancel. Some hard times await us in Panama.

The interview with Velasco Ibarra was a miserable failure. The master of ceremonies, a Sr. Anderson, answered our pathetic pleas for help by commenting on the ups and downs of life, suggesting that we are currently experiencing a low, but that a high will come, etc.

On Sunday I discovered some coastal areas similar to river floodplains, but it was the company of Dr. Fortunato Safadi and his friend, an insurance salesman, who made the trip really interesting. Later in the day, he said that hard times await us in Panama, but the question is whether Panama itself awaits us…

After collecting the Guatemalan visa without any trouble, we went—still without the Panamanian visa—to buy boat tickets. An argument ensued because the company representative flatly refused to sell us tickets without first wiring the Colón Panamá Company. The answer came back the following evening and was a firm negative. That was Saturday. The Guayos, a small boat due to leave on Sunday, has postponed its departure until Wednesday.

Calica got a lift to Quito in a private truck.

We tried again on Monday, this time with a $35 money transfer in my and García’s names, because we were determined to leave first. It didn’t work, and with that behind us and only one miserable bullet left to fire we sent Calica a telegram telling him to wait for us. That evening I met Enrique Arbuiza, the insurance salesman, who told us he might be able to organize things, and the following morning, today, we met the head of a tourism business. He also refused, but gave us new hope, saying that the company taking us to Panama could issue us with a ticket. The insurance salesman, also a friend of the Guayos captain, took me along to see him and present him with our problem. The captain nearly exploded, but calmed down after we had a chance to explain things a little; we agreed to wait for the final answer this afternoon.

At any rate, we sent another telegram to Quito, revising the first, so that Calica could continue alone, at least to Bogotá. Our plan is to wait for the final answer, and then either for two of us to go to Panama, or for the three of us to clear out as soon as possible.

We will see…

We’ve seen nothing: over an hour of futile waiting for the captain of the Guayos to show up. We’ll decide once and for all what to do tomorrow, but either way Andro Herrero is staying. He thinks one of us should stay behind as a contact point in Guayaquil, and that at any rate it’s easier for two to slip through than three. Although that’s true, we sense a hidden motive in all this and think that some love affair must be keeping him here; he’s so mysterious, no one knows what he’s up to.

I spent a terrible day prostrate with asthma, and with nausea and diarrhea from a saline purgative. García did nothing all day, so the uncertainty continues.

We’re fixated on the visa for Panama. But with everything ready, they hit us for an extra 90 sucres, which none of us had, so it was put off until the afternoon. Nevertheless, I met the consul, who invited me to visit an Argentine ship. They treated us well enough and gave us mate, but the consul made me count out the 10 sucres for the boat religiously. It’s a barge like the Ana G., which holds so many memories for me.17 I want to point out the following fact: the soldiers guarding the enrolment offices have the initials “US” on their backs.

We now have the visa, with its wonderful words: “Fare paid Panama to Guatemala.” There’s going to be a tremendous row. Today I ate with García on board the Argentine ship, and we were treated like kings. They gave us American cigarettes and we drank wine, not to mention the stew. The rest of the day, zero.

Two more days. A sad Saturday of upsetting farewells, a sad Sunday of further postponement. On Saturday I had the typewriter all but sold, until the residue of my bourgeois desire for property stopped me at the last moment. Now it’s apparently too late, although I’ll find out today. On Sunday evening, the ring was also pretty much a sure sale.

In the morning, when all our plans seemed to be in ruins, without a cent or any way of finding one, news of the postponement seemed like a gift from heaven. But when the engineer was asked for a date and replied, dubiously, “Who knows, it could be Thursday,” our enthusiasm hit the floor. Five more days mean another 120 sucres, more difficulty paying for things, etc.

And now more and more days, and the machine couldn’t be sold, and there’s virtually nothing left to burn. Our situation is precarious, to say the least—not a single peso left, debts of 500 and potentially 1,000—but when? That is the question. We’ll be leaving now on Sunday, if there’s not another delay for some unforeseen reason.

Guayaquil [October 21, 1953]

[To his mother]

I am writing you this letter (who knows when you’ll read it) about my new position as a 100 percent adventurer. A lot of water has flowed under the bridge since the news in my last epistle.

The gist is: As Calica García (one of our acquisitions) and I were traveling along for a while, we felt homesick for our beloved homeland. We talked about how good it was for the two members of the group who had managed to leave for Panama, and commented on the fantastic interview with X.X., that guardian angel you gave me, which I’ll tell you about later. The thing is, García—almost in passing— invited us to go to Guatemala, and I was disposed to accept. Calica promised to give his answer the next day, and it was affirmative, so there were four new candidates for Yankee opprobrium.

But then our trials and tribulations in the consulates began, with our daily pleas for the Panamanian visas we required and, after several psychological ups and downs, he seemed to decide not to go. Your suit—your masterpiece, the pearl of your dreams—died heroically in a pawnshop, as did all the other unnecessary things in my luggage, which has been greatly reduced for the good of the trio’s18 economic stability—now achieved (whew!).

What this means is that if a captain, who is a sort of friend, agrees to use an old trick, García and I can travel to Panama, and then the combined efforts of those who want to reach Guatemala, plus those from there, will drag along the straggler left behind as security for the remaining debts. If the captain I mentioned messes it up, the same two partners in crime will go on to Colombia, again leaving the security here, and will head for Guatemala in whatever Almighty God unwarily places within their reach. […]

Guayaquil, [October]24

After a lot of coming and going and many calls, plus a discreet bribe, we have the visa for Panama. We’ll leave tomorrow, Sunday, and will get there by the 29th or 30th. I have written this quick note at the consulate.

Ernesto

At sea, now, reviewing these last few days. The desperate search for someone to offer us something for the gear we wanted to sell; the evasive buyer of the ring, who finally caved in; our friend Monasterio’s ultimate gesture in giving us 500 sucres and speaking with the landlady of the boarding house. The always cold, never satisfactory moments of farewell, when you find yourself unable to express your deep feelings.

We’re in a first-class cabin, which for those travelers who have to pay would be terrible, but for us, it’s perfect. For roommates we have a talkative Paraguayan, who is doing a lightning trip around the Americas by air, and a nice guy from Ecuador—both pretty hopeless. García is seasick, but after throwing up and taking some Benadril is dead to the world. For the evening there’s a mate session with the engineer.

I’ve learned of the death of an aunt of mine in Buenos Aires, through a diplomat I met in Chile and whom I bumped into unexpectedly on the Argentine ship. He gave me the news almost as a passing comment.

Marta is not worth seeing, or so it’s said, so we didn’t disembark at the port. But the following day at Esmeraldas we let loose and spent a dollar visiting the whole town, in celebration of leaving Ecuador.

One of our compañeros, the Ecuadorean, came across a cousin he had never met before—they became firm friends, and took us on a stroll through a tropical forest on the outskirts of town.

After this, we’ve had a whole day at sea, which I’ve found to be quite beautiful, although Gualo García hasn’t enjoyed it at all. On leaving Esmeraldas, a tramp was discovered—a stowaway— who was returned to port. It brought back fond memories of other times.

Now we are settled in Panama without a clear direction,19 in fact with nothing clear at all except the certainty of leaving. Incredible things have happened. In order: we arrived, and without any trouble, the customs inspector calmly checked through our things, another employee stamped and returned our passports, and from Balboa, the port where we disembarked, we set off for Panama City.

Fatty Rojo had left the address of a boarding house, so we went there and were put up in a corridor for a dollar a day each.

Nothing out of the ordinary that day, but on the next we received a big surprise. Opening our letters at the Argentine consulate, we found one from Rojo and Valdovinos, announcing the marriage of the latter. We were most intrigued, until the girl, Luzmila Oller,20 arrived and told us all about the wedding and other things. The event had sparked a revolution in her family. The father has done a bunk and the mother refuses to see him, so the guy just gets up and continues on his trip to Guatemala, without a good screw or even, it seems, a serious attempt at passion.

The girl is very nice and seems quite intelligent, but she’s too Catholic for my taste.

Perhaps the Argentine consul will arrange something for us or perhaps we’ll write for a magazine called Siete. Maybe I’ll give a lecture. So maybe we’ll be able to eat tomorrow.

Nothing new, except that tomorrow I am to give a lecture on allergies, saying something about the organization of the medical faculty in Buenos Aires. The students gave me a warm welcome at the college. I met Don Santiago Pi Suñer, the physiologist, and in another context we met Dr. Carlos Guevara Moreno, who struck me as an intelligent demagogue, knowledgeable in mass psychology but not in the dialectics of history. He is very nice and friendly and treated us with deference. He gives the impression that he knows what he’s doing and where he’s going, but that he wouldn’t take a revolution beyond what is strictly indispensable to keep the masses content. He admires Perón. We might be able to publish two articles, one in Siete, the other in the Sunday supplement of Panamá-América.

Luzmila has received a letter from Óscar Valdovinos, 16 pages long. She exudes happiness.

I gave the famous lecture to an audience of 12, including Dr. Santiago Pi Suñer, for $25. I wrote an account of the Amazon, $20, and one about Machu-Picchu, probably $25.

We’re going to move to a place that’s rent free. We met a young painter, not a bad guy. The guys are about to be expelled from the FUA for having visited consulates and traveled in a foundation airplane from Guayaquil to Quito. They’ve got Valdovinos by the balls in Guatemala because he sent a declaration in the name of “some anti-Peronist young Argentines.” I don’t know how it will all be sorted out. We went for a very pleasant walk along the beach at Riomar with Mariano Oteiza, president of the Panamanian Students Federation.21

My article about the Amazon has appeared in Panamá-América; the other is still fighting for a place.22 Our situation is bad. We don’t know whether we’ll be able to leave, or how. The Costa Rican consul is an idiot and won’t give us a visa. We met a sculptor, Manuel Teijeiro, an interesting man.

The struggle is getting heavy. Met the painter Sinclair, who studied in Argentina. A good guy.

The best so far is the trio of Adolfo Benedetti, Rómulo Escobar and Isaías García. All great guys.23

We still haven’t checked out the canal properly. We went there the other day but were too late and it was closed.

I have to add another two names: Everaldo Tómlinson and Rubén Darío Moncada Luna.

The last days in Panama were a waste of time. The Costa Rican consul wouldn’t give us the visas until we showed him not just tickets out of the country but also tickets in. We had to ask Luzmila to lend us the money. We couldn’t get the camera out, or get the PAA [Panamanian Airlines] to refund the fares to Costa Rica. We missed a farewell party they gave for Luzmila, or rather, I missed it, because Gualo had a complex about the way they regarded us and didn’t want to go. Luzmila was a little cold in the end.

For the second piece they gave me $15, thanks to the effort another decent guy put in, José María Sánchez.

We left Panama with $5 in our pockets, meeting at the last moment an interesting character from Córdoba. Ricardo Luti is a botanist and asthmatic who has been in the Amazon region and Antarctica and is thinking about doing a trip through the center of Latin America via Paraguay, the Amazon and the Orinoco—my old idea.

We’re now in the center of Panama. The suspension on the truck has gone completely, with no sign of the truck driver, who went to David for spare parts and hasn’t returned. We ate a little rice and an egg for breakfast. At night the mosquitoes won’t let you sleep, by day the mosquitoes won’t let you live (poetic). The region is relatively elevated, not at all hot, with abundant forests and heavy downpours of rain.

I made a lightning visit to Palo Seco, where an American Jewish couple has been living for 20 years. They don’t seem particularly informed, but they devote themselves exclusively to the sick.

Rubén Darío Moncada only got it half right. The driver turned out to be worse than a motherfucker and on a bend when the brakes failed, we went flying. I was on top of the truck, and when I saw the disaster coming, I threw myself as far away as possible, then rolled a little further, until I came to rest with my head in my hands. When the hubbub had passed, I got up to help the others, realizing that no one but me had a scratch on them—I escaped with a grazed elbow, torn pants and a very painful right heel.

I slept the night in the truck driver Rogelio’s house. Gualo stayed on the road looking after our things.

The next day we missed the 2 p.m. train and resigned ourselves to one leaving at 7 the next morning. Arriving at Progreso, we then had to hoof it to the Costa Rican coast,24 where we were received very well. I played football despite my bad foot.

We left early the next morning, and after losing our way we found the right road and walked for two hours through mud. We made it to the railway terminal, where we got talking with an inspector who, incidentally, had wanted to go to Argentina but hadn’t been given leave. We reached the port and pressured the captain for the fare. He conceded, but not on the question of accommodation. Two employees took pity on us, so here we are installed in their rooms, sleeping on the floor and feeling very content.

The famous “Pachuca,” which transports pachucos (bums), is leaving port tomorrow, Sunday. We now have beds. The hospital is comfortable and you can get proper medical attention, but its comforts vary depending on your position in the Company.25 As always, the class spirit of the gringos is clearly evident.

Golfito is a real gulf, deep enough for ships of 26 feet to enter easily. It has a little wharf and enough housing to accommodate the 10,000 company employees. The heat is intense, but the place is very pretty. Hills rise to 100 meters almost out of the sea, their slopes covered with tropical vegetation that surrenders only to the constant presence of human activity. The town is divided into clearly defined zones, with guards to prevent unwanted movement. Of course, the gringos live in the nicest area, a little like Miami. The poor are kept separate, shut away behind the four walls of their own homes and restrictive class lines.

Food is the responsibility of a decent guy who is now also a good friend: Alfredo Fallas.

Medina is my roommate, also a decent guy. There’s a Costa Rican medical student, the son of a doctor, as well as a Nicaraguan teacher and journalist in voluntary exile from Somoza.

The “Pachuca” left Golfito at 1 p.m. with us on board. We were well stocked with food for the two-day voyage. The sea became a little rough in the afternoon and the Río Grande (the ship’s real name) started to be tossed about. Nearly all the passengers, including Gualo, started vomiting. I stayed outside with a black woman, Socorro, who had picked me up and was as horny as a toad, having spent 16 years on her back.

Quepos is another banana port, now pretty much abandoned by the company, which replaced the banana plantations with cocoa and palm-oil trees that gave less of a return. It has a very pretty beach.

I spent the whole day between the dodges and smirks of the black woman, arriving in Puntarenas at 6 in the evening. We had to wait a good while there, because six prisoners had escaped and couldn’t be found. We visited an address Alfredo Fallas had given us, with a letter from him for a Sr. Juan Calderón Gómez.

The guy worked a thousand miracles and gave us 21 colones. Arriving in San José we remembered the scornful words of a joker back in Buenos Aires: “Central America is all estates: you’ve got the Costa Rican estate, the Tacho Somoza estate, etc.”

A letter from Alberto, evoking images of luxury trips, has made me want to see him again. According to his plan, he’ll go to the United States in March. Calica is destitute in Caracas.

We’re firing blanks into the air here. They give us mate at the embassy. Our supposed friends don’t seem to be good for anything. One is a radio director and presenter, a hopeless character. Tomorrow we’ll try to get an interview with Ulate.

A day half wasted. Ulate was very busy and couldn’t see us. Rómulo Betancourt has gone to the countryside. The day after next we’ll appear in El Diario de Costa Rica with photos and everything, plus a big string of lies.26 We haven’t met anyone important, but we did meet a Puerto Rican, a former suitor of Luzmila Oller, who introduced us to some other people. Tomorrow I might get to visit the Costa Rican leprosy hospital.

I didn’t see the leprosarium, but I did meet two excellent people: Dr. Arturo Romero, a tremendously cultured man who due to various intrigues has been removed from the leprosarium board; and Dr. Alfonso Trejos, a researcher and a very fine person.

I visited the hospital, and just this morning, the leprosarium. We have a great day ahead. A chat with a Dominican short-story writer and revolutionary, Juan Bosch, and with the Costa Rican communist leader Manuel Mora Valverde.

The meeting with Juan Bosch was very interesting. He’s a literary person with clear ideas and leftist tendencies. We didn’t talk literature, just politics. He characterized Batista as a thug among thugs. He is a personal friend of Rómulo Betancourt and defended him warmly, as he did Prío Socarrás and Pepe Figueres.27 He says Perón has no popular influence in Latin America, and that in 1945 he wrote an article denouncing him as the most dangerous demagogue in the Americas. The discussion continued on very friendly terms.

In the afternoon we met Manuel Mora Valverde, who is a gentle man, slow and deliberate, but he has a number of tic-like gestures suggesting a great internal unease, a dynamism held in check by method. He gave us a thorough account of recent Costa Rican politics:

“Calderón Guardia is a rich man who came to power with the support of the United Fruit Company and through the influence of local landowners. He ruled for two years until World War II, when Costa Rica sided with the Allies. The State Department’s first measure was that land owned by local Germans should be confiscated, particularly land where coffee was cultivated. This was done, and the land was subsequently sold, in obscure deals involving some of Calderón Guardia’s ministers. This lost him the support of all the country’s landowners, except United Fruit. The Company employees are anti-Yankee, in response to its exploitation.

“As it was, Calderón Guardia was left with no support whatsoever, to the point where he could not leave his house for the abuse he was subjected to on the streets. At that point the Communist Party offered him its support, on the condition he adopt some basic labor legislation and reshuffle his cabinet. In the meantime, Otilio Ulate, then a man of the left and personal friend of Mora, warned the latter of a plan Calderón Guardia had devised to trap him. Mora went ahead with the alliance, and the popularity of Calderón’s government soared as the first gains began to be felt by the working class.

“Then the problem of succession was posed as Calderón’s term was coming to an end. The communists, in favor of a united front of national reconciliation to pursue the government’s working-class policies, proposed Ulate. The rival candidate, León Cortés, was totally opposed to the idea and continued to stand. At this time, using his paper El Diario de Costa Rica, Ulate began a vigorous campaign against the labor legislation, causing a split in the left and Don Otilio’s about-face.

“The elections saw the victory of Teodoro Picado, a feeble intellectual ruined by whisky, although relatively left leaning, who formed a government with communist support. These tendencies persisted during his entire period of office, although the chief of police was a Cuban colonel, an FBI agent imposed by the United States.

“In the final stages, the disgruntled capitalists organized a huge strike of the banking and industry sectors, which the government did not know how to break. Students who took to the streets were fired on and some were wounded. Teodoro Picado panicked. Elections were approaching and there were two candidates: Calderón Guardia again, and Otilio Ulate. Teodoro Picado, opposing the communists, handed over the electoral machine to Ulate, keeping the police for himself. The elections were fraudulent; Ulate was triumphant. An appeal to nullify the result was lodged with the electoral commission, with the opposition also requesting a ruling on the alleged violations, stating it would abide by the verdict. The court refused to hear the appeal (with one of the three judges dissenting), so an application was made to the Chamber of Deputies and the election result was set aside. A giant lawsuit was then launched, with the people by now roused to fever pitch. But here a parenthesis is needed.

“In Guatemala, Arévalo’s presidency had led to the formation of what came to be known as the Socialist Republics of the Caribbean. The Guatemalan president was supported in this by Prío Socarrás, Rómulo Betancourt, Juan Rodríguez, a Dominican millionaire, Chamorro and others. The original revolutionary plan was to land in Nicaragua and remove Somoza from power, since El Salvador and Honduras would fall without much of a fight. But Argüello, a friend of Figueres, raised the question of Costa Rica and its convulsive internal situation, so Figueres flew to Guatemala. The alliance came into operation; Figueres led a revolt in Cartago and with arms swiftly took over the aerodrome there, in case any air support was necessary.

“Resistance was organized rapidly, however, and the people attacked the barracks to obtain weapons, which the government was refusing to give them. The revolution had no popular support—Ulate had not participated—and was doomed to failure. But it was the popular forces headed by the communists who had won—a conclusion extremely disconcerting for the bourgeoisie, and with them, Teodoro Picado. Picado flew to Nicaragua to confer with Somoza and obtain weapons, only to find that a top US official would also be at the meeting, and who demanded, as the price for assistance, that Picado should eradicate communism in Costa Rica (thereby guaranteeing the fall of Manuel Mora), and that each weapon supplied would come with a man attached to it—signifying an invasion of Costa Rica.

“Picado did not accept this at that time, as it would have meant betraying the communists who had supported him throughout the struggle. But the revolution was in its death throes and the power of the communists so frightened the reactionary elements in the government that they boycotted the defense of the country until the invaders were at the gates of San José and then abandoned the capital for Liberia, close to Nicaragua. At the same time, the rest of the army went over to the Nicaraguans, taking all the available ammunition. A pact was made with Figueres, underwritten by the Mexican embassy, and the popular forces actually laid down their weapons in front of that embassy. Figueres did not keep his side of the deal, however, and the Mexican embassy was unable to enforce it because of the hostility of the US State Department. Mora was deported. It was pure luck he escaped with his life as the plane he was traveling in came under machine-gun fire. The plane landed in the US Canal Zone, where the Yankee police arrested him and handed him over to the Panamanian chief of police, at that time Colonel Remón. The Yankee journalists wanting to question him were expelled, and then he had an altercation with Remón and was locked up. Finally he went to Cuba, from where Grau San Martín expelled him to Mexico. He was able to return to Costa Rica during the Ulate period.

“Figueres was faced with the problem that his forces consisted of only 100 Puerto Ricans and the 600 or so men who formed the Caribbean Legion. Although he initially told Mora that his program was designed for a 12-year period and that he had no intention of surrendering power to the corrupt bourgeoisie represented by Ulate, he had to make a deal with the bourgeoisie and agreed to give up power after only a year and a half, an undertaking he fulfilled after he had fixed the election machinery to his benefit and organized a cruel repression. When the time was up, Ulate returned to power and kept it for the appointed four years. It was not a feature of his government to uphold the established freedoms or to respect the progressive legislation achieved under the previous governments. But it did repeal the anti-landowner “law on parasites.”

“The fraudulent elections gave Figueres victory over the candidate representing the Calderón tradition, who now lives as a closely monitored exile in Mexico. In Mora’s view, Figueres has a number of good ideas, but because they lack any scientific basis he keeps going astray. He divides the United States into two: the State Department (very just) and the capitalist trusts (the dangerous octopuses). What will happen when Figueres sees the light and stops having any illusion about the goodness of the United States? Will he fight or give up? That is the dilemma. We shall see!”

A day that left no trace: boredom, reading, weak jokes. Roy, a little old pensioner from Panama, came in for me to look at him because he thought he was going to die from a tapeworm. He has chronic salteritis.

The meeting with Rómulo Betancourt did not have that history-lesson quality of the one with Mora. My impression is that he’s a politician with some firm social ideas in his head, but otherwise he sways toward whatever is to his best advantage. In principle, he is solidly with the United States. He spoke lies about the Río Pact and spent most of the time raging about the communists.

We said our good-byes to everyone, especially León Bosch, a really first-rate guy, then took a bus to Alajuela and started hitching. After several adventures we arrived this evening in Liberia, the capital of Guanacaste province, which is an infamous and windy town like those of our own little province, Santiago del Estero.

A jeep took us as far as the road permitted, and from there we started our long walk under quite a strong sun. After more than 10 kilometers, we encountered another jeep, which took us as far as the little town of La Cruz, where we were invited to have lunch. At 2:00 we set off for another 22 kilometers, but by 5 or 6 p.m. night was falling and one of my feet was a misery to walk on. We slept in a bin used for storing rice and fought all night over the blanket.

The next day, after walking until 3 in the afternoon, making a dozen or so detours around a river, we finally reached Peñas Blancas. We had to stay there as no more cars were heading to the neighboring town of Rivas.28

The next day dawned to rain and by 10 a.m. there was still no sign of a truck, so we decided to brave the drizzle and set off for Rivas anyway. At that moment, Fatty Rojo appeared in a car with Boston University license plates. They were trying to get to Costa Rica, an impossible feat because the muddy track on which we ourselves had been bogged a few times was actually the Panama-Costa Rica highway. Rojo was accompanied by the brothers Domingo and Walter Beberaggi Allende. We went on to Rivas and there, close to the town, we ordered a spit roast with mate and cañita, a kind of Nicaraguan gin. A little corner of Argentina transplanted to the “Tacho estate.” They continued on to San Juan del Sur, intending to take the car across to Puntarenas, while we took the bus to Managua.

We arrived at night, and began the rounds of boarding houses and hotels to find the cheapest accommodation. In the end we settled on one where for four córdobas we each had a tiny room without electricity.

We started out the next day tramping round the consulates and encountering the usual idiocies. At the Honduran consulate Rojo and his friends appeared; they’d been unable to get across and were now rethinking the plan because of the outrageous price being charged. Things were then decided very quickly. The two of us would go with Domingo, the younger Beberaggi, to sell the car in Guatemala, while Fatty and Walter would travel by plane to San José in Costa Rica.

That evening we had a long session, each of us giving their perspective on the question of Argentina. Rojo, Gualo and Domingo were intransigent radicals; Walter was pro-Labor; and myself, a sniper, according to Fatty Rojo at least. Most interesting for me was the idea Walter gave me of the Labor Party and Cipriano Reyes— very different from the one I had already. He described Cipriano’s origins as a union leader, the prestige he slowly won among the Berisa meat-packers and his attitude toward the Unión Democrática coalition, when he supported the Labor Party (founded by Perón at that time) in the knowledge of what it was doing.

After the elections, Perón ordered the unification of the party, causing its dissolution. A violent debate ensued in the parliament, in which the Labor supporters, headed by Cipriano Reyes, didn’t bend. Finally talks got underway for a revolutionary coup d’état, headed by the military under Brigadier de la Colina and his assistant, Veles, who betrayed him by telling Perón what was happening.

The three main leaders of the party—Reyes, Beberaggi and García Velloso—were imprisoned and tortured, the first barbarically. After a time, the judge, Palma Beltrán, ordered the prisoners’ conditional release into police custody, while the state prosecutor appealed against the sentence. Beberaggi managed to escape when the parliament was in session and made his way secretly to Uruguay; all the others were arrested and are still in prison. Walter went to the United States and graduated as an economics professor. In a series of radio talks he denounced the Perón regime in no uncertain terms, and was stripped of his Argentine citizenship.

In the morning we left for the north, having left the others on the plane, and reached the border as it was closing.

We only had $20. We had to pay on the Honduran side. We crossed the whole narrow strip that is Honduras at that point and made it to the other border, but couldn’t pay because it turned out to be too expensive. We slept in the open air—the others, on rubber mattresses, me, in a sleeping bag.

We were the first to cross the border and continued north. It was very slow going because the number of punctures we’d had left us with some rotten spare tires. We reached San Salvador and set about wrangling free visas—which proved possible with the help of the Argentine embassy.

We continued on to the [Guatemalan] border,29 where we paid the surcharge with a few pounds of coffee. On the other side it cost us a torch, but we were on our way, albeit with only $3 in our pockets. Domingo was tired, so we stopped to sleep in the car.

After a few minor incidents, we made it in time for breakfast at Óscar and Luzmila’s boarding house, only to find that they had somehow fallen out with the landlady. We had to find another boarding house where we wouldn’t have to pay upfront. That evening, December 24, we went to celebrate at the house of Juan Rothe, an agronomist married to an Argentine girl, who greeted us like old friends. I slept a lot, drank too much and fell sick immediately.

For the next few days I had a terrible asthma attack, so I was immobile because of my asthma and also the festivities. By December 31 I was well again, but was careful what I ate during the celebrations.

I’ve met no interesting people worth mentioning. One evening I had a long session with [Ricardo] Temoche, a former APRA30 deputy. According to him, APRA’s principal enemy is the Communist Party—for him neither imperialism nor the oligarchy has any significance; the Bolsheviks are the irreconcilable enemy. At the same party was a noted economist, Carlos D’Ascolli, but he was too drunk to speak to me. After my attack, and at the end of the festivities, we witnessed the end of what had seemed to be a serious romance between Domingo Beberaggi and a girl called Julia. On Sunday he sold the car and flew to Costa Rica.

Juan Rothe is going to Honduras as a technician, so he threw a farewell barbecue. It was formidable in every sense. The only person not drunk was me because of my diet. I visited Peñalver,31 a supporter of Acción Democrática and a specialist in malaria, who has got a few things moving for me. Now I am close to the minister, but he doesn’t have much weight.

Another contact I’ve made is a strange gringo32 who writes bits and pieces about Marxism and has it translated into Spanish. The intermediary is Hilda Gadea,33 while Luzmila and I put in the hard yards. So far we’ve made $25. I’m giving the gringo Spanish lessons.

Another find has been the Valerini couple. She is very pretty; he’s very drunk, but a decent guy. They agreed to introduce us to an éminence grise within the government: Mario Sosa Navarro. We’ll see what comes of it.

The days pass with no resolution. In the afternoons I work with Peñalver for a while, but he pays me nothing. In the mornings I go out to sell paintings of my Black Christ of Esquipulas, who is adored by people here, but that also earns me nothing as no sales are made. Among the interesting people I’ve met is Alfonso Bawer Pais,34 a lawyer and president of the Banco Agrario, a man with good intentions. Edelberto Torres is a young communist student and son of Professor Torres35 who wrote a biography of Rubén Darío. He seems like a decent guy. No news from the éminence grise. I had an intense political discussion with Fatty Rojo and Gualo, in the home of an engineer named Méndez.36

Nothing new in terms of finding work. The administrative efforts at the Ministry of Public Health have failed. For now the only game in town appears to be a radio contract; although nothing’s come of it yet, it looks promising. We’ve met no one interesting these last few days. I put on the ACTH from 8 a.m. until 2 or so in the afternoon. I’m fine.

No prospects in the near future. The éminence grise did not keep the appointment we made with him.

A Saturday without trouble or glory. The only good thing was a serious chat with Sra. Helena de Holst,37 who is close to the communists on many things and strikes me as a very good person. In the evening I had a chat with Mujica38 and Hilda, and a certain little adventure with a plumpish schoolteacher. From now on, I’ll try to keep a daily journal, and familiarize myself more with the political situation here in Guatemala.

A Sunday without novelty, until the evening when I was asked to attend to one of the Cubans who was complaining of severe abdominal pain.39 I called an ambulance and we waited in the hospital until 2 a.m., when the doctor decided it was necessary to wait before operating. We left him under observation.

Earlier, at a party in Myrna Torres’s home, I met a girl who was showing some interest in me and talked about the possibility of some work for 40 quetzals.40 We’ll see.

Another day without trouble or glory. There’s a prospect of 10 quetzals (we’d get 25 commission) and accommodation. We’ll see. The Cuban41 was going to look into this in his department.

One more day without trouble or glory. A refrain that seems to be alarmingly repetitious. Gualo vanished all day, to do nothing, and I seized the chance to do nothing as well. In the evening I went to visit the college where I may get work. […]

No new developments. I spoke to the Bolivian ambassador, a good man and more than that in terms of his politics. In the evening we went to the opening of the second congress of the CGTG,42 a confused affair apart from the speech of the FSM [World Federation of Trade Unions] delegate, a great speaker.

Another day gone… Evidence has now been published that the plot people were speaking about really did exist. We have the possibility of an order but it will be necessary to present a program like respectable people. I am a representative for leather and illuminated hoardings—no job. Lots of mate.

A new day without trouble or glory. There’s nothing expected from [Jaime] Díaz Rozzoto.43 I went out with a girl who seems promising. […] Anita [Torriello] asked us to pay for the boarding house and Hilda can’t give us more than $10. We owe $60 or more. Tomorrow is Sunday, so we should not despair.

Two more days with no change to our routine. I have asthma again, but it seems I’ll be able to beat it. Gualo is off to Mexico with Fatty Rojo to stay for a month. I have a letter for the director of the IGSS,44 Alfonso Solórzano, we’ll see what happens. If nothing crystallizes, one of these days I’ll pack my bags and emigrate to Mexico as well. I have written a grandiloquent article titled, “The Dilemma of Guatemala,”45 not for publication, just for my own pleasure […].

The asthma is getting worse all the time. I have started drinking mate and stopped eating corncakes, but it keeps getting worse. Tomorrow I think I’ll pull out a tooth and see if that isn’t the root of the problem. I’ll also see if I can finally solve the currency problem.

More days to add to my diary notes. Days full of inner life and nothing else. A collection of all kinds of disasters and the never changing spiral of hopes. There is no doubt about it, I’m an optimistic fatalist […].

I’ve had asthma these days, the last few confined to my room hardly going out at all, although yesterday (Sunday) we went with the Venezuelans and Nicanor Mujica to Amatitlán. There we got into a heavy argument, all of them against me, except for Fatty Rojo who said I don’t have the moral ability to engage in a debate. Today I went to see about the possibility of work as a doctor: 80 a month, for one hour’s work a day. In the IGSS they told me with utmost certainty that there are no positions. [Alfonso] Solórzano was friendly and to the point. Now the day can come to an end with the old full stop. We’ll see.

But we’ve seen nothing. As I was in no state to move, I sent Gualo to take them my qualifications, but later Herbert Zeissig started asking for more information about me, whether or not I was affiliated with the party, etc. Hilda didn’t speak to Sra. Helena de Holst but […] sent her a telegram. The asthma continues. Gualo is getting impatient to leave.

Two more days to add to this succession, and nothing new is expected. I didn’t move because of the asthma, but I feel it’s approaching a climax, with vomiting at night. Helenita de Holst has tried to get in touch with me, so in fact that’s where I’m placing most of my hope. Hilda Gadea is still very worried about me, and is always coming by and bringing things. Julia Mejías found me a house in Amatitlán to stay for the weekend. Herbert Zeissig avoided having to make a final decision, sending me to see V.M. Gutiérrez46 to obtain the support of the Communist Party, which seems doubtful to me.

One more day, although hope is renewed as my health begins to improve. Today will be decisive, and Gualo will definitely leave tomorrow at dawn; he’s not sleeping here. Rojo paid half the bill at the boarding house. I owe 45 quetzals. I still don’t know whether I’ll be going to Amatitlán tomorrow; when Gualo arrives I’ll know for sure either way.

I visited Sra. de Holst, who was very kind to me, but her promises, no doubt sincere, are dependent on the minister for public health — and he’s already given me the cold shoulder. In the evening I visited Julia Valerini, who had lost a little boy and had had a shocking headache all day.

Two long days, with a strange chill, especially outside in the evenings, with shivering and so on. After a youth festival organized by Myrna,47 where I’d gone with Hilda for a change, I beat it to the banks of a lake to sleep, and then the shivering started. The next day, Sunday, I bought some provisions at the market and walked very slowly to the other side of the lake. I had a wonderful siesta, then tried to drink some mate but the water was too bitter. At nightfall I made a fire for a barbecue, but the wood was no good, I was already freezing, and the barbecue was shit. I threw half of it in the lake to destroy any trace of the ignominy.

I was walking back slowly when I came across a drunk who made the trip seem shorter. A van picked us up and here I am.

Monday saw nothing worth mentioning, except for Peñalver’s pronouncement that he’s working on securing a medical position for me. Sra. de Holst doesn’t know anyone well enough in the PAR [Partido Acción Revolucionario], the main party in that department, to ask them for something like that. We’ll see.

A day of conscious desperation, due not to the cyclical crisis but the cold analysis of reality. My job as overseer at the Argentine’s is the only sure thing. I’ve given up the idea of being a doctor for the trade unions; the job in a peasant community and the other one from Helenita de Holst are still up in the air. I met Pellecer48—in my view, neither fish nor fowl.

The rest continues on its daily course. I meet people on both the left and the right. If things continue like this, in no time I’ll be working as a bill poster to pay my expenses and other things. We’ll see.

I finally received a letter from home and know the answer on the mate—no, no, no. The day slipped by because I had no energy and took to my room for a nap. The boss Dícono didn’t leave, only his wife, who gave me a mango that should have been thrown away.

Tomorrow I might go to the country for the job at the colony.

Several days have passed, two of them at La Viña colony. A spectacular place, in a landscape similar to the Sierras Grandes in Córdoba, and human material to be worked into shape. But they lack that essential ingredient: the desire to pay for a doctor of their own. My stay was wonderful, but on the way back I realized something had disagreed with my stomach, and I had to vomit. Then it calmed down a little. We spent the next day in Chimaltenango, the little town where the youth festival49 was being held. The place was very pretty, and each of us did whatever took their fancy. Our little group was the same as always, with Hilda Gadea, the gringo and a Honduran woman…

Nothing happened on Monday of particular interest, just another day closer to the goal: May 1.

After confusion over the matter of introductions, I went to the farm with Peñalver, who rather demagogically proposed me for the job. The director asked me how much I wanted, and I kept it low at 100 quetzals for twice a week, on the condition they spend 25 a month on laboratory equipment. I have to go back on Saturday to see what the outcome is.

The whole farm business is very murky. Answer postponed. I went to Tiquisate and it didn’t go well, but there’s some hope of not such a good job, with board and lodging. That leaves the one through Sra. de Holst, and then the thing with the Argentine. Tomorrow, we’ll see.

It’s not tomorrow but the day after and, of course, we haven’t heard a thing. Nor does it look like we’ll hear anything any time soon. Having made up my mind completely, I tried to see Guerrero but wasn’t able to find him. The only thing worth mentioning is a letter from Mamá in which she tells me Sara50 has had an operation and is not good; they found cancer in her large intestine…

Today I’m in a great mood. It was Julia Mejías who introduced me to García Granados, who said he would give me a job to go to Petén for $125. I still need authorization from the union, which I’ll try to get tomorrow. If it happens it’ll be great […]. Tomorrow could be a day of further disappointment, or my big day in Guatemala. I am optimistic.

Now I’m not so optimistic—far from it. I spoke with Sibaja, but he paid me no attention. At 4 p.m. tomorrow he’ll tell me once and for all whether he’s been able to influence the head of the union. On another front, tomorrow Lily will speak to her brother. It will probably come to nothing again. We’ll see. The Geografía work continues, although today I just wandered around, not doing a lot.

Two more days and today, yes, a little bit of hope. Yesterday, nothing.

Sibaja is good for nothing, but today I went on my own account to see the head of the union, a man looking to keep his job, an anticommunist, given to intrigue, but seemingly disposed to help me. I didn’t sing quite the appropriate tune, but neither did I risk much. He’ll give me a final answer on Wednesday.