EXERCISE ANSWERS

fire/ranger/tropical = forest

carpet/alert/herring = red

forest/fly/fighter = fire

cane/daddy/plum = sugar

friend/flower/scout = girl

duct/worm/video = tape

sense/room/place = common

pope/eggs/Arnold = Benedict

fair/mind/dating = game

date/duck/fold = blind

cadet/outer/ship = space

dew/badger/bee = honey

ash/luck/belly = pot

break/food/forward = fast

nuclear/feud/values = family

collector/duck/fold = bill

car/French/shoe = horn

office/mail/step = box

circus/around/car = clown

sand/age/mile = stone

catcher/dirty/hot = dog

fly/milk/peanut = butter

tank/notch/secret = top

thief/cash/larceny = petty

artist/great/route = escape

hammer/line/hunter = head

blank/gut/mate = check

list/circuit/cake = short

master/child/piano = grand

cover/line/wear = under

beer/pot/laugh = belly

trip/left/goal = field

man/sonic/star = super

bus/illness/computer = terminal

type/ghost/sky = writer

full/punk/engine = steam

break/black/cake = coffee

car/human/drag = race

liberty/bottom/curve = bell

drunk/line/fruit = punch

buster/bird/wash = brain

fruit/hour/napkin = cocktail

old/dog/joke = fart

toad/sample/foot = stool

1. Remember the Duncker candle problem? In this case, like the box of tacks, a holder is more than a holder. Remove the sleeping bag from its sack and then slip the sack over the forked branch to make a paddle.

2. Did you disassemble the pen in your mind to discover a hollow plastic tube? If so, you might have guessed that MacGyver cuts the fuel line and rejoins it so that fuel flows through the hollow pen tube.

3. The reason you likely got this one quickly is that you didn’t have to stray far from your functional fixedness of a gutter’s common use. Instead of transporting rainwater, MacGyver uses the gutter to transport diamonds. The lampshade is a funnel.

4. Renaming the “scarf” as a length of cloth may have helped you see that it could be used as a sling with the rock as its projectile. Now unseating a bad guy just takes good aim.

5. Dutch lensmaker Hans Lippershey invented the first telescope in 1608. MacGyver’s answer to this puzzle is a twist on the classic, with newspaper rolled into a tube and the watch crystal opposite the magnifying glass at the open ends.

6. MacGyver fills the plastic bags with water and ties them to either side of a length of fishing line. He wraps the line around the knob so that water bags hang off either side, then pokes a hole in one bag. As that bag lightens, the other drops and the knob turns.

7. He pours the water into the radiator and starts the car. When the water heats up, he cracks the eggs into the radiator. As they cook, the egg whites plug the slow leaks.

8. The rake head is a grappling hook and the garden hose is rope. As you progress through these puzzles, are you finding it easier to release functional fixedness?

9. The soccer ball is a red herring, used only as a mold to sculpt the newspaper into the shape of a spherical hot-air balloon, which is powered by flaming cotton balls.

10. A bicycle is made of many parts, and so if you deconstructed it in your mind, you can probably imagine a couple of ways to shoot a ball bearing. MacGyver’s answer was to make a slingshot from the handlebars and an inner tube.

1. Dark ages

2. Big bad wolf

3. Capital punishment

4. Little league

5. Grave error

6. Ambiguous

7. Excuse me

8. Tea for two

9. Go stand in the corner

10. A round of applause

11. Split personality

12. Waterfall (or standing water)

13. Paralegal

14. Too big to ignore

15. Sit down and shut up

16. Search high and low

17. Somewhere over the rainbow

18. A home away from home

19. Beating around the bush

20. Diamond in the rough

21. A little on the large side

22. Just between friends

23. Lying down on the job

24. Rock around the clock

Congratulations to anyone who got “broad jump” or “money belt”!

board/blade/back = switch

land/hand/house = farm

hungry/order/belt = money

forward/flush/razor = straight

shadow/chart/drop = eye

way/ground/weather = fair

cast/side/jump = broad

back/step/screen = door

reading/service/stick = lip

over/plant/horse = power

5. WASON SELECTION TASK: EVIDENCE FOR PRACTICAL INTELLIGENCE

In general, the Wason Selection Task requires realizing that in each case, you only have to find a condition that would falsify the claim—not conditions that would lend it further support. Only about 10 percent of people get the first two questions right. But about 75 percent get the third and fourth questions right. To Leda Cosmides, John Tooby, and other evolutionary psychologists, this is because we have evolved the ability to reason about the real world much more accurately than we reason about abstract problems. In other words, evolution has hardwired us for a practical intelligence that is distinct from general intelligence.

Here, finally, are the answers:

1. If there were a square on the back of the 4, or an even number on the back of the square, it would negate the claim. Did you flip the star too? There’s no need. No matter if the number on back is even or odd, it would do nothing to negate the claim that even numbers hold stars.

2. Same here—did you flip the 4? You don’t have to. Only finding an odd number on the A or a vowel on the 7 would negate the claim.

3. In this classic case, it’s easier to see that you have to test that the seventeen-year-old isn’t drinking alcohol, and test that the beer isn’t being consumed by anyone under twenty-one. It doesn’t matter what the twenty-three-year-old is drinking and it doesn’t matter who’s having the soda.

4. Finally, you have to make sure that the thing that went up came down, and that the thing that never came down didn’t ever go up in the first place. Flip “went up” and “didn’t come down” to check.

6. IF, THEN, BECAUSE: MAKE IMPLICIT LEARNING EXPLICIT

N/A

Generally, situational judgment tests (SJTs) are scored by measuring participants’ responses against the responses of top performers—for example, comparing a job candidate’s answers to the answers chosen by a panel of the best employees. In this case, the scenarios and best answers are adapted from ones used in a number of existing SJTs, though the situations involved are also very social and so the specifics of your job or your neighbor might affect the “best” actions.

1. Best: (B) Quietly decline the request. Worst: (A) Quietly accept the friend request.

2. Best: (C) Wait for twenty minutes and then talk to your friend about the appropriateness of her actions. Worst: (B) Placate watching parents by immediately explaining to your friend that disagreement between kids is normal and offer to teach your friend mediation techniques.

3. Best: (C) Explain to your crew that your head’s on the line and you really need their help to make the deadline. Worst: (D) Do nothing. Delays in roadwork happen all the time and being behind schedule in this case is perfectly understandable.

4. Best: (D) Bring your neighbor a six-pack of Pabst Blue Ribbon as a thank-you for letting you borrow the mower. Wait until he’s had at least two before explaining what happened. Worst: (B) Bring your neighbor to the scorched circle and insist he pay for nine square feet of sod to cover the hole.

5. Best: (B) Do nothing and hope that your job performance eventually speaks for itself. Worst: (A) Ask for a demotion so that you can work your way up from the bottom like everyone else.

6. Best: (C) Laugh and suggest that everyone must have strange mannerisms, and as an example offer a lighthearted impression of your unkind coworker. Worst: (A) Stop the meeting and ask to be assigned to a different group.

7. Best: (D) Have a private heart-to-heart with your coworker, explaining your concerns. Worst: (C) Next Monday, buy a plate of treats from the best bakery in town and anonymously set it next to your coworker’s underpowered treats in the lunchroom. See what happens.

8. Best: (C) Don’t touch it with a ten-foot pole. You want no part in this mother’s eventual realization. Worst: (B) Suggest that perhaps cooing about her beautiful baby in public may make parents with less beautiful children feel bad.

9. Best (though this is by far the most ambiguous—don’t you think?): (D) Be friendly and engage the mother in chitchat. Then suggest support services in the community for struggling parents. Worst: (B) Pointedly suggest that if the wine seems a less good deal without the coupon, perhaps the mother might opt for the milk and corn, instead.

8. NONSENSE AND IMPLICIT LEARNING

N/A

In this test, there are 12 prototypical dingbits (P)—beetles that share all nine dingbit features. There are also 24 low-distortion dingbits with one or two changed features (LD); 24 neutral non-dingbits with three to six distortions (N); 24 high-distortion non-dingbits with seven or eight changed features (HD); and 12 anti-dingbits that share none of the prototypical dingbit features (A). Compare the solutions to your answers. Now add up the incorrect answers for each of the types, P, LD, N, HD, and A. What percentage of each type did you label as a dingbit? Was it 100 percent of P’s and 0 percent of A’s? If you chose to complete half the test, then train implicit learning, and return for the second half, did your percentages change?

In Knowlton and Squire’s experiment (in which they used giraffe-like animals and the category “peggle”), both amnesiacs and healthy subjects correctly called about 90 percent of the prototypical animals peggles, 80 percent of the low-distortion animals peggles, about 60 percent of the neutral animals peggles (oops!), about 40 percent of the high-distortion animals peggles (double oops!), and incorrectly labeled about 25 percent of the anti-peggles as peggles (triple oops!). How does your implicit category learning stack up?

10. PROBLEM-SOLVING OPERATIONS: RANDOM, DEPTH-FIRST, BREADTH-FIRST, AND MEANS-ENDS ANALYSIS SEARCH

N/A

11. MATCH: INITIAL STATE TO OPERATIONS

1. Depth-first search: There’s a specific order in which these things must be done, for example underwear before pants. Once you’ve made an underwear choice, it’s counterproductive to revisit the decision. Depth-first allows one pass through the system, generating one solution.

2. Breadth-first search: This is a thinly disguised maze problem—a depth-first search generates many solutions, which you can then compare.

3. Random search: It’s quicker and easier to pick socks than it is to wonder what is the best strategy for picking socks.

4. Means-ends analysis: To close the gap between your current state (hungry) and your goal state (not hungry) requires the subgoal of moving away from the vending machine, to the ATM, before returning with cash.

1. Feisty Kindergarteners

Assumption: All the kindergarteners must be on the ground. It’s impossible to arrange four points equidistantly from each other on a plane. But stick one of the kindergarteners on the play structure and the other three in an equilateral triangle at its base and it’s easy.

2. Battleship

Assumption: The lines must be horizontal or vertical columns or rows of evenly spaced stars. Also, if you thought of a star, this seductive but incorrect answer could have formed its own false assumption.

Assumption: You must be the driver. Instead, give the keys to your best friend, who takes the old lady to the hospital while you wait for the bus with your dream date (who is now duly impressed).

4. Household Pets

Assumption: All households have some pets. Instead, all it takes is one petless household for the product of all pets in US households to be exactly zero.

5. Coconut Grove

Assumption: The doors opened outward. Instead, the doors of the Coconut Grove nightclub opened inward, and with people pressed against them, they couldn’t be opened. In modern buildings, doors open out.

6. Not That Prisoner’s Dilemma

Assumption: The prisoner cut the rope in half along its width. Instead, the prisoner divides the rope in half lengthwise. When he ties these two strands together, the rope is twice its original length. (Apparently it’s still strong enough to hold him.)

7. Cut the Card

Assumption: The edges of the card must maintain their original dimensions. Instead:

Assumption: The ratio 5:4 matters. Without this assumption, you see that at the unluckiest, you will draw one white sock and one black sock, at which point the third sock you draw is guaranteed to match one already drawn, giving you a pair. The maximum number of socks you must draw to guarantee a pair is 3.

9. Jane and Janet

Assumption: Jane and Janet are the only siblings born. In fact, they are triplets (or quads, or quints, etc.) with an unmentioned child or children and thus not twins. Another answer is to imagine Jane and Janet as children of a lesbian couple with simultaneous due dates, making them sisters by family but not by blood.

10. Matchstick Math

Assumption: You can only move matchsticks that make roman numerals. Instead, move a stick that makes one of the operators, as follows:

N/A

14. INSPIRED, DIVERGENT THINKING

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

19. RUBE GOLDBERG MACHINE DESIGN CHALLENGE

N/A

20. RETRAIN ATTENTION, RETRAIN INTUITION

N/A

1. Without follow-up from the specialist, feedback is nonexistent. Your intuition may be comparing this case to similar, previous cases, but without knowing how any of these cases resolve, this wicked training environment can lead to incorrect intuition.

2. A strange shirt in the laundry was unambiguous feedback. But it was only one case. Beware what Eugene Sadler-Smith calls the tyranny of small numbers.

3. Similar to the ER doc in the first example, an HR manager who never hears about job performance trains intuition in a wicked environment. Sure, your intuition separates the wheat from the chaff, but then, without feedback, how can you know if your guess was right or wrong?

4. Mightn’t candidates’ job success be due to six months of training rather than to your evaluation of their skills? Like this chapter’s example of the waitress who intuits that well-dressed people tip more, and then creates evidence for it by treating these customers better, perhaps training creates the connection between candidates and success.

5. With consistent, relevant, unambiguous feedback, this is a kind training environment.

6. Certainly this is a wicked training environment—feedback is ambiguous and perhaps your coworker’s terseness has nothing to do with you at all. However, human intuition about others’ emotions is notoriously precise. In situations of social intuition, ask yourself how much information you may be taking in subconsciously. Does this extra information still leave you stranded in a wicked training environment, or are things perhaps kinder than you initially thought?

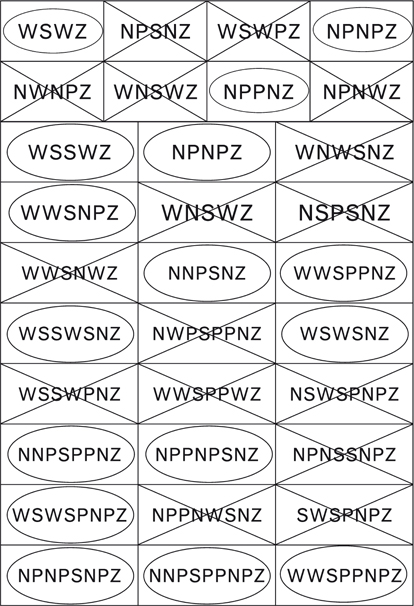

About that rule: following is a diagram of the artificial grammar used to create the letter strings in this exercise.

Starting at the first, empty dot and following the arrows, the rule takes only permissible paths through the chart. So you could take the path WSSWZ, but can never get the letter pairs WN, WP, SZ, PW, NW, and NS. Letter strings that contain these pairings are illegal. And in the test portion of this exercise, legal strings were intermixed with strings that were identical but for the insertion of one of these illegal pairings. The answers follow.

How did you do? In a study that compared the performance of healthy and amnesiac subjects on this artificial grammar task, psychologists Barbara Knowlton and Larry Squire found that healthy subjects correctly identified 63.5 percent of the grammatical items while incorrectly thinking that 41.5 percent of the non-grammatical items also fit the rule. Amnesiacs performed almost identically, further showing that intuitive learning is independent of traditional learning. These results mean that on this test, you should’ve correctly circled about ten of the grammatical items along with six of the non-grammatical items. If you beat the mean, give yourself a pat on the back for being especially intuitive. If not, consider searching online for further examples of artificial grammar tasks to train this skill.

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

Pretest Answers

1-c, 2-j, 3-a, 4-e, 5-g, 6-t, 7-m, 8-n, 9-v, 10-p, 11-t, 12-r, 13-t, 14-e, 15-i

Letter Series Training

The first task of training is a scaled-down version of the test. Here, in each set of four letter pairs, circle the pair that doesn’t belong.

1. AB, TS, XY, GH

2. GJ, NQ, KM, DG

3. UV, PO, ML, DC

4. BB, BB, BC, BB

5. JK, HG, EF, NO

6. JI, ON, BD, GF

7. Dd, FF, pP, JK

8. IK, BD, PS, LN

9. BC, LM, PR, HI

10. Jj, Ii, kK, Hh

11. CH, HM, FK, NR

12. EC, BA, NL, HF

13. IJ, CD, LM, PO

14. DF, GF, VU, JI

15. FH, PR, DE, TV

16. ON, FE, HI, KJ

You may have noticed certain kinds of relationships in these letter pairs. In the series themselves, these relationships are frequently hidden inside longer strings. And so the ACTIVE training taught participants to recognize the following four kinds of patterns:

• Identity: A pattern in which a chunk, however long, is cycled or periodically repeats without change—for example, trkodtrkodtrko … or the n’s in annbnncnndnnenn …

• Next: Sequential patterns, in most cases with chunks following alphabetical order—for example, abstcduvefwx …

• Skip: Similar to “next” but with predictable holes in the sequence—for example, acegikmo …

• Backward: Instances of the first three series, reversed—for example, gfedcbazy …

The training also taught participants how to diagram letter series to represent these patterns. When you see repeating snippets (“identity”), underline them. Use brackets to show any instances of alphabetical order, as in “next.” Make tick marks to show letters skipped in a pattern. Mark slashes in the string to show repetitions or “periods” in the pattern. Mark a left-pointing arrow above letters to show “backward.” Here are examples from the pretest, diagrammed to show patterns:

1. [b c]/[b c]/[b c]/[b c]/b …

2.

3. g f e/f e d/e d c/d c b …

4. [t u][b c][u v][c d][v w]d …

5. c ’ e x/d ’ f x/e ’ g x/f ’ h x/ …

6. [h i] p/[i j] q/[j k] r/[k l] s/l m] …

Now it’s your turn to practice diagramming the patterns in letter series. Underline and draw brackets, tick marks, and slashes to show the patterns in the remaining items from the pretest:

7. e f b g h b i j b k l b …

8. h i j k i j k l j k l m k l m …

9. t p q t q r t r s t s t t t u t u …

10. p m o p n o p o o p p o …

11. x b q x c r x d s x e …

12. a b v a b u a b t a b s a b …

14. e m o e r o e n o e q o e o o …

15. e f t u f g u v g h v w h …

Test Answers

1-b, 2-f, 3-e, 4-u, 5-x, 6-t, 7-k, 8-v, 9-t, 10-f, 11-m, 12-p, 13-i, 14-g, 15-o.

Did you improve? In fact, these are the same patterns as in the pretest, only starting in difference places. Here is how the questions were reordered in the test: 13-1, 3-2, 6-3, 14-4, 7-5, 1-6, 15-7, 8-8, 9-9,10-10, 5-11, 2-12, 11-13, 4-14, 12-15. Are there patterns you missed both times? If so, take another look at how you diagrammed these series in the test. Now write out these twice-missed patterns yourself, starting at a different letter of the alphabet. Don’t forget to search online for additional opportunities to practice your new pattern-recognition skills.

31. A COGNITIVELY INVOLVED LIFESTYLE

N/A

32. A COGNITIVELY KIND LIFESTYLE

N/A

Paul Baltes showed three life tasks that are especially necessary for the development of wisdom: selection, optimization, and compensation (SOC). Basically, in selection we set goals, in optimization we choose a strategy to pursue them, and then in compensation we reflect on outcomes that may not be quite what we intended. To Baltes, this SOC framework allows a person to tenaciously pursue goals but also gives them the vision to adapt them when necessary. And by passing many times through the selection-optimization-compensation cycle, we train wisdom.

According to Baltes’s extensive testing and validation, the proverbs in this test are or aren’t representative of SOC values. For example, When the wind doesn’t blow, grab the oars represents compensation, the “C” in SOC. These SOC proverbs, he writes, “reflect active life-management strategies such as developing clear goals, investing into goal pursuit, and maintenance in the face of losses.” Unfortunately, other proverbs like Good things come to those who wait represent the non-SOC values of “a relaxed life style, waiting for opportunities and good fortune to present itself, and giving in to losses,” Baltes says.

Score your proverb choices according to the following answers. More than twelve correct implies wisdom. Then reflect on your incorrect answers. Why was the other answer wiser? In what way does it more accurately match Baltes’s SOC framework? Baltes shows that this reflection leads to wisdom.

1. A—Optimization

2. A—Selection

3. B—Compensation

4. A—Selection

5. B—Selection

6. B—Compensation

7. B—Optimization

8. A—Optimization

9. A—Compensation

10. B—Optimization

11. B—Selection

12. A—Optimization

13. B—Optimization

14. A—Selection

15. A—Compensation

16. B—Selection

17. B—Compensation

18. A—Compensation

N/A

Harvard and University of Chicago psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg pioneered the idea of stages of moral development—basically, the goal of this exercise is to help you progress through them. First mine your written answers for reasoning that aligns with Kohlberg’s stages, listed below from lowest to highest—what’s your baseline level of moral reasoning? Then revise your answers to address concerns from higher on the scale of moral reasoning. Here, in condensed form, are descriptions of Kohlberg’s stages:

1. Obedience and punishment: Others are nonexistent and right and wrong depend on immediate reward and punishment.

2. Self-interest: Others exist but only insofar as they can further the reasoner’s self-interest—right and wrong depend on what you can gain from a choice.

3. Conformity: The reasoner wants to be liked and approved of by others and by society—choices depend on conforming to understood norms.

4. Law-and-order: Right and wrong exist to maintain social order and for that reason laws must be obeyed. If one person disobeyed the law, maybe many would.

5. Human rights: Right and wrong are calculated based on respect for basic rights like life and justice, and when laws violate rights, rights take precedence.

6. Universal human ethics: Reasoning takes into account multiple individual viewpoints and right and wrong are calculated selflessly based on the sum of benefit.

N/A

37. ANCIENT WISDOM VS. NONSENSE

38. INTRINSIC VS. EXTRINSIC MOTIVATION

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

42. PRACTICE LIKE YOU PLAY (SO YOU CAN PLAY LIKE YOU PRACTICE)

N/A

43. RECOGNIZING AND LABELING EMOTIONS

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

52. AVOID TEMPTATION (SO YOU DON’T HAVE TO RESIST IT)

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

1. Despite a much larger sample screaming otherwise, to Caroline and John the image of John’s fizzled TV is immediately available. This is the availability heuristic—we’re prone to making decisions based on first images, information, or memories that pop to mind, not necessarily the overall most likely images, information, or memories.

2. In the way this information is presented, both statements are logical. This, despite the belief bias screaming that hairless cats can’t be furry. Did you disregard logic in favor of what you generally hold to be true?

3. This is the gambler’s fallacy (or some people go even further to call it the hot hand fallacy): every time Pete steps to the plate he has an independent .314 chance of getting a hit, despite three lucky at-bats in a row. It’s like a coin flip: every time you flip a coin the odds are 50-50 no matter how many heads you’ve previously flipped in a row. Despite the streak, Pete has the same chance he’s always had of getting a hit (unless his three hits in a row slightly raised his batting average).

4. Jacob shouldn’t let his father-in-law’s experience stop him from taking the drug; it doesn’t have any effect on his likelihood of having the same response to it. Our oversized tendency to respond to this kind of individual anecdote could be called the availability heuristic at work again, but psychologists also call this a base rate fallacy: we’re likely to base our opinions on one personal case rather than the statistics of the larger system.

5. This is a classic example of small sample bias butting heads with the statistical phenomenon known as regression to the mean. Early in a baseball season, players have only a few at-bats—a “small sample” of what they’ll have by the end of the season. You might hit a lucky .450 over the season’s first twenty at-bats, but come October and 550-ish at-bats later, players tend to regress to the mean, sinking into more realistic batting averages.

6. Most people choose the only color they shouldn’t: red. This is due to the ambiguity bias—you don’t know if there are 2 or 21 white or black balls and so red seems like the surest bet. That’s despite probability putting 10.5 white or black balls in the bag compared to only 10 red ones.

7. There are many possible measurements of the Great Pyramid, which can be combined in myriad ways, including—yes—to get the date of Michael Jackson’s death, or pretty much anything else if you put your mind to it. This is confirmation bias—cherry-picking only the information that supports our preconceived point of view.

8. In fact, the population of Botswana is about two million. But your guess was likely much higher due to the anchoring bias. Like Steve Jobs pricing the iPhone at $500, anchoring the possible population of Botswana at forty million made it seem not only possible but likely.

9. Did you join 90 percent of Tversky and Kahneman’s subjects in thinking it more likely Linda is both bank teller and feminist? If you stop to think about it for a minute, you realize that in order for that to be true, the first statement (that she’s just a bank teller) must also be true. This is the conjunction fallacy—we assume specific things that make intuitive sense are more likely than a less well-supported general condition that, nonetheless, must be true on the way to the specifics.

10. There are two things going on here. First is the framing effect—you interpret the same information differently depending on how it’s presented. The second is loss aversion—humans are generally more worried about losing x amount than they are excited about gaining the same x amount.

11. Here’s another question: which do you find more truthful, the phrase “What sobriety conceals, alcohol reveals,” or the phrase “What sobriety conceals, alcohol unmasks”? And now you probably see the punch line: experiments show that people find rhyming phrases more truthful than the same wisdom that doesn’t rhyme. It just rings true! Psychologists call this the rhyme-is-reason effect.

62. BIASES, HEURISTICS, AND LOGICAL FALLACIES

1. Scope fallacy—consider the common (albeit misquoted) phrase all that glitters is not gold, as in the description of the scope fallacy. Now, if you had to connect is-not or not-gold, which would you connect? With this wording, you can’t know if all that glitters is the substance not-gold, or if all that glitters is-not gold. Same with Disraeli—is it “half the cabinet are-not asses,” meaning that at least a distinct 50 percent act unlike asses, or is it “half the cabinet are not-asses,” in which case it implies that half are? In any case, Plato would agree that it’s not much of an apology.

2. Ambiguity—Bill Clinton didn’t lie … he just didn’t tell the truth. In this case the phrase “sexual relations” is ambiguous. Now the whole world knows the comment was, er, fallacious.

3. Guilt by association—this is a type of association fallacy with the formal structure A is a B; A is also a C; therefore B is a C. In this and many related cases, Nazis are bad; Nazis practiced psychiatry; therefore psychiatry is bad.

4. Appeal to nature—what can be more right than nature? And as a corollary, everything unnatural is bad, including GMO foods and man-made vaccines.

5. Denying the antecedent—Ah, how Turing jests! His example is about as logical as stating that if you’re hungry after eight hours, you’re human. You’re not hungry after eight hours, so you’re not human.

6. Tu quoque (You also)—More generally, tu quoque is a form of ad hominem, which is more colloquially described as I’m right because you suck. In this case, Osama bin Laden attacks the character of his accuser rather than the content of the argument.

7. False dilemma—In this case, Pawlenty implies the choice must be between his plan and Obama’s, when there are certainly other options. His argument looks like this: Something has to be done; this is something; therefore this has to be done. Not so much.

8. Appeal to authority—if the authority in question is an actual expert with definite facts or opinions, appealing to authority can, in fact, add logical punch to an argument. However, in this case it helps to know that the CBO was frank about its lack of confidence in its own numbers. Bachmann states as fact what the authority took with a grain of salt.

9. Post hoc ergo propter hoc—when one thing comes after or with another, we have the unfortunate predisposition to imagine that the first caused the second. Scroll through non-journal science headlines and in the course of a day, you’ll find fifty claims of false causation.

10. False dilemma—Only a Sith deals in absolutes, as in Anakin Skywalker’s ultimatum to his former teacher Obi-Wan Kenobi: “If you’re not with me, then you’re my enemy.” False dilemma disregards the world’s shades of gray.