EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE

“There’s an old graph about empathy and sales performance,” says John (Jack) Mayer, University of New Hampshire professor and one of the pioneers of emotional intelligence research. “Some empathy is good—being clueless isn’t helpful. But then too much empathy is bad. It hurts sales.”

Mayer saw this firsthand during two years between college and grad school when he had a gig as a writer/researcher studying car sales managers in Michigan. He remembers that “in some dealerships, the most outperforming salespeople would be there gagging with laughter over having sold some poor person a clunker for $500 over invoice.” These salespeople had enough empathy to connect with the customer and make the sale—but not so much that it bothered them to rip someone off.

In Mayer’s research on emotional intelligence, he identified four factors that seemed central to the way humans experience and use emotions: perceiving emotions, reasoning with emotions as a piece of the decision puzzle, understanding emotions and being able to verbalize them, and being able to appropriately and effectively manage emotions.

“We saw that emotions are like chess pieces,” says Mayer, “and each moves in its idiosyncratic way. Anger has its moves; happiness and love have their own moves. People who recognize, reason with, understand, and manage these emotions can play the game.”

To see if facility with this piece-pushing has any real-world purpose, Mayer, his grad student at the time Marc Brackett, and Rebecca Warner asked people to fill out a 1,500-item survey that included “everything from what’s in the fridge to what clubs they belong to, to how many pictures they have on the mantel,” he says. And then he and his colleagues tried to discover which factors on these surveys pointed toward outcomes representative of strong emotional kung fu, such as less drug abuse, less fighting and arguments, more contact with parents, how someone is perceived in the workplace, and so on.

Sure enough, they were able to show, for example, that students with high emotional intelligence (EI) have lower rates of drug use and teachers with high EI get more support from their principals. Employees with high EI have higher job performance, especially when their IQ is low (implying that emotional intelligence can help compensate for low general intelligence—and also that these skills are distinct). EI is even implicated in resilience—the more EI you have, the higher your chances of bouncing back after trauma or negative life events.

So which is it? Like empathy in car salesmen, is there an optimal degree of emotional intelligence or is more EI simply better?

Mayer’s former grad student Marc Brackett—who now happens to be director of the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence—solved this seeming paradox, illustrating his explanation with a story about his own experience in the stock market. “I’m obsessive-compulsive about my stocks,” he says, “but I don’t buy and sell every day, because I’m aware that it’s a game for me and I don’t actually allow myself to do stupid things.” The difference between Brackett and Wall Street traders whom many studies show are led by their emotional noses into imprudent trades is that, while Brackett and these traders both experience emotions powerfully, Brackett overlays these emotions with the understanding that he needn’t act on them.

And according to Jack Mayer, this combination of being able to both recognize and manage emotions is precisely what makes up the best EI: “intuition overlain with reason—both the visceral experience of emotion and the cerebral ability to direct it.” This is the difference between the useful and the detrimental experience of emotion: If you can’t reason with emotions, to a large degree you’re better off being oblivious to them.

For example, imagine you’re feeling insecure in a meeting. If you’re unaware of this insecurity, you simply act like that idiot we all know, laughing at inappropriate times, stepping on toes, boasting or mumbling, and generally making an ass of yourself. Now imagine you’re aware of your insecurity but unable to regulate it. It’s even worse—like watching your life train-wreck in super slow motion. But if you can overlay emotional perception with emotional logic, you can learn to manage and even control this insecurity and thereby avoid looking like an ass.

To accomplish this, Marc Brackett recommends an approach similar to becoming a ninja. Seriously. “My other career is teaching martial arts,” Brackett says, “and you’re required to learn different skills to earn different-colored belts, different ranks.” Start simply, he says, learning to recognize the seven basic emotions of anger, fear, disgust, contempt, joy, sadness, and surprise. Then progress to understanding, labeling, expressing, and regulating these emotions. Brackett names these steps according to the acronym RULER.

The last step, regulating, is the difference between using emotions and being irrationally led by them. It’s what keeps Brackett from day trading and would allow the underperforming car salesman to decide whether or not to act on his empathy.

Of course, emotions don’t always require redirection. Maybe after overlaying intuition with analysis, you still feel like a stock trade is a smart choice—using analysis to validate useful emotions can be as powerful as using it to regulate away useless ones.

So the answer to whether it’s best to recognize emotions or live blissfully unaware of them is this: if you can’t put the final “R” on RULER, you might as well not put on the first. But if you can both be sensitive to emotions and control them, you have a powerful tool in navigating the emotional landscape of life.

RECOGNIZING AND LABELING EMOTIONS

As part of their EI training intended for businesses and schools, researchers Andrew Morris and his colleagues use art to train emotional recognition and labeling—the first “R” and “L” in Marc Brackett’s RULER. (Though their list of basic emotions doesn’t exactly match Brackett’s.) They note that in one study, this training incidentally led to a 30 percent increase in community service hours in those trained. Here’s how it works:

Do a quick Google image search for the term “portraits” or “portrait.” Then read the list of emotions below and pick the best emotions to label the faces you see. Then (and this is important!) list the nonverbal clues you used to reach your answers. This training matches Marc Brackett’s description of making the implicit learning of emotion explicit—not just knowing, but dissecting how you know.

Once you’ve mastered portraits, try it with abstract art and poems (you could use the poetry archives at the New Yorker, Atlantic, and thedailyverse.com). Then try it with music.

EMOTIONS:

Anger: fury, outrage, resentment, wrath, exasperation, animosity, annoyance, irritability, hostility, hatred

Sadness: grief, sorrow, gloom, melancholy, self-pity, loneliness, dejection, despair

Fear: anxiety, apprehension, nervousness, concern, consternation, misgiving, wariness, qualm, edginess, dread, fright, terror, panic

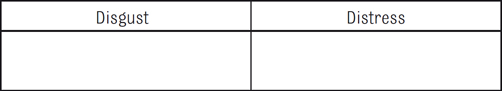

Disgust: contempt, disdain, scorn, abhorrence, aversion, distaste, revulsion

Shame: guilt, embarrassment, chagrin, remorse, humiliation, regret, mortification

Enjoyment: happiness, joy, relief, contentment, bliss, delight, amusement, pride, thrill, rapture, sensual pleasure, gratification, satisfaction, euphoria, whimsy, ecstasy

Love: acceptance, friendliness, trust, kindness, affinity, devotion, adoration, infatuation

Surprise: shock, astonishment, amazement, wonder

Click here for answers.

UNDERSTANDING EMOTIONS

Children quickly develop what are called first-order beliefs—the ability to infer what someone else is thinking. For example, a child might say of a begging Labrador that “the dog wants a treat.” Trickier are second-order beliefs—knowing what someone thinks someone else is thinking. For example, explaining that a storybook character gave a dog a treat because the character knew the dog wanted it. This is emotional understanding. It’s also the distinction between a lie and a joke. For example, in a study of autistic children’s ability to distinguish lies from jokes, psychologists Susan Leekam and Margot Prior point out that “the ability to distinguish a lie from a joke involves deciding whether a person wants to be believed.” And sure enough, people with low emotional intelligence, as is generally the case in those with autism spectrum disorders, have a tough time sorting the jokers from the liars.

Working through this distinction can help you improve your ability to understand emotion—the “U” in Marc Brackett’s RULER. The following stories present instances of lying or joking. Your job is not only to distinguish the two but to justify your answers in the language of second-order beliefs—what do the characters in these stories think the other characters believe? How does one character’s intention to be believed or disbelieved make the distinction between a lie and a joke? Don’t look in the back of the book—the answers aren’t there. Instead, the process of reasoning through these on your own whether you’re technically right or wrong is what will improve your ability to understand emotions in your own life.

After returning from the community rec center, a six-year-old tells his father that he finally summoned the courage to go down the large, yellow twisty slide into the water. He didn’t actually go down the slide.

A coworker asks if you parked in the Employee of the Month spot. You say no, it’s not your car. But it is.

A coworker asks if you parked in the Employee of the Month spot. He’s the employee of the month. You say no, it’s not your car. But you know that he knows that it is.

A dad tells his kids the bath is ready—the perfect temperature!—but when the first kid hops in, he’s surprised to find it ice cold.

Your nervous Labrador leaves a steaming pile in a hidden corner of the veterinarian’s office. When the receptionist asks whose dog is responsible, you don’t say anything, but you know she probably suspects you.

Your neighbor wonders if perhaps your Labrador snuck into his yard and ate the largest koi from his backyard pond. Having just buried in your own backyard the mostly-eaten remains of said koi, you say no—of course your dog didn’t eat the fish.

A four-year-old tells her father that Templeton, the pet guinea pig, has escaped. When Dad looks, there’s Templeton still sitting in the cage. The girl says that must be a new guinea pig and not Templeton.

Your mother-in-law wonders if you know anything about the whereabouts of her teeth? You disavow all knowledge. In fact, you’ve inserted them into the motion-activated singing bass over the fireplace, which she gave you for Christmas. You hope your wife notices later and not your mother-in-law now.

All three of the new pet fish, named after Disney princesses, are dead. You surreptitiously replace them with live look-alikes. When the kids notice the fish have slightly changed color, you blame it on water temperature. Everyone is mollified, but you think they suspect the truth.

A friend says you’ve got to meet this guy/girl he knows—you’d, like, totally hit it off! But the date turns out to be the friend’s somewhat odd brother/sister.

A four-year-old points and yells, “Spider on your shirt!” You jump six feet in the air. There is no spider.

A husband tells his wife that of course he remembered to turn off the sprinkler like she asked before they left the house. He says that he’s forgotten his wallet and while “retrieving” it from home, turns off the sprinkler.

Two kids are terrified of a tiny black spider that’s run under the edge of a carpet. The father says he knows where it is—under a specific corner. With trepidation, the kids get ready to lift the corner. The father has sneakily placed a gigantic rubber tarantula under this corner.

Click here for answers.

EXPRESSING EMOTIONS

Now on to the “E” in RULER: expressing emotions. Successful emotional expression matches emotion to situation. For example, if you’re looking forward to a reward, the most reasonable emotion to feel would be hope, whereas once the reward is actually present, the appropriate emotion is joy. If the same were true of a future/current punishment, you might feel trepidation and then distress. Generally, there are five characteristics of situations that work together to determine the “correct” emotion: motivational state (are you avoiding something bad or seeking something good?), situational state (is the good or bad thing predicted or actually present?), probability (is the outcome certain or uncertain?), legitimacy (do you deserve the outcome?), and agency (is the situation caused by circumstance, others, or yourself?).

A 1990 study by Ira Roseman asked participants to pick apart these five factors. Basically, Roseman had participants recall an experience of joy and then one of relief, or affection and then pride, or sadness and then fear—and then had participants rate these emotions according to the five factors. Consensus over 161 subjects showed which emotions match which situations. For a massive table of results, search online for “Appraisals of Emotion-Eliciting Events,” but, for one example of many, they found that the emotion of disgust has high legitimacy (it’s deserved) whereas shame does not.

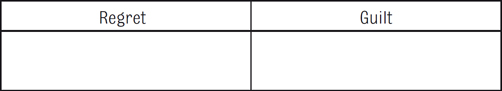

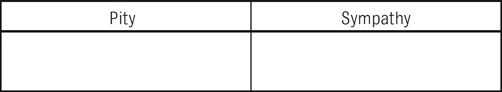

Following are the pairs of emotions that Roseman and his colleagues used in their study, along with a couple more recommended by Marc Brackett. For each emotion, write the memory of an experience when you felt it. Once you’ve finished listing experiences, revisit these experiences to discover what, exactly, makes you feel, for example, regret rather than guilt, or joy rather than relief. If you’re up for it, use the language of the five characteristics of emotional situations to describe the motivational state, situational state, probability, legitimacy, and agency of your emotional experiences. This exercise is a bit tricky but will boost your ability to express situationally appropriate emotions.

Here are the paired emotions:

Click here to download this exercise.

Click here for answers.

REGULATING EMOTION

Last but not least, the all-important final “R” in Brackett’s RULER! A 1996 study found more than two hundred ways to regulate emotion, including exercise, venting, drinking, and seeking social support. Luckily, Stanford’s James Gross boils it down to the following five major categories of emotional self-regulation strategies. For each, learn about the strategy and then list ways in which the strategy does or could apply to your life.

Approaching or avoiding people, places, and things to regulate emotion. For example, staying away from the racetrack or seeking out a good friend. Beware overbalancing the short-term gains of avoiding an emotionally stressful situation with long-term losses. For example, a shy person who avoids parties may further lose the ability to socialize.

Exercise: List a situation that you find emotionally challenging and then another that is emotionally recharging:

________________________________________________

________________________________________________

________________________________________________

For example, a flat tire on the way to an important meeting is crazy-making until you decide to make it a conference call. Researchers call this problem-focused coping. This can be internal as well as external—for example, you could change the meeting to a conference call (external) or you could just decide it’s not so important after all (internal).

Exercise: How have you sculpted a situation’s emotion? List one time you got needlessly worked up and one time you made the best of a bad thing:

________________________________________________

________________________________________________

________________________________________________

This falls into the three subcategories of distraction, concentration, and rumination. Distraction can be focusing on ceiling tiles or on that proverbial happy place in your heart and mind. Concentration is blotting out emotion with an all-consuming activity, be it thinking about your garden or actually gardening. And rumination focuses attention on emotions themselves and their consequences rather than fixating on the situations that cause them, though it’s the most fraught of the three because rumination on sadness can lead to depression and rumination on negative consequences of emotion can lead to anxiety about expressing them.

Exercise: List one distraction and one thing you can concentrate on to regulate your emotion:

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

You can choose the personal meaning you attach to a situation or reframe a situation to transform the emotion it elicits. For example, you might reframe an exam as an opportunity to improve rather than a high-stakes test of your personal worth. Or you can reappraise failure in light of a task’s partial successes. Or you can compare yourself to those less fortunate.

Exercise: Pick a situation that makes you feel bad or anxious or stressed out. How could you reframe this situation in a positive light?

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

This includes regulating an emotion itself through psychiatric drugs, relaxation strategies, or the like, and also exerting control over the expression of the emotion. Some people call this second step repression, and it can have negative consequences, as seen in studies showing that inhibiting the expression of emotion actually makes you feel the bad aspects of it more keenly.

Exercise: List a situation in which you tend to repress emotion. Now list a situation in which you think you could and should show more emotion:

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

Click here for answers.

WORDS AND MEANING

Chris Argyris of the Harvard Business School has a nice technique for training people to understand the hidden meanings of speech, but it takes a partner and some work. With your partner, record and transcribe a meaningful conversation (or have Google Voice transcribe the recording for you). Make a copy of the transcript for yourself and another for your partner. Note in the margins what you were thinking while you were speaking and also note what you think the other person meant but didn’t say. Have your partner do it, too. Then compare notes—how close were your interpretations to your partner’s intended meanings? Argyris uses this exercise to highlight the disconnect between words and thoughts—both the small and large dishonesties in our own speech and the implicit assumptions that we make when listening.

Click here for answers.