CHAPTER THREE

Sister-Wives and Suffragists

THE SAME YEAR that Susan B. Anthony and Sojourner Truth attempted to register to vote, a newspaper called the Woman’s Exponent began publication in the territory of Utah. Although not an official organ of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS)—the official name of the religion as distinct from its popular designation as Mormon—it was closely linked to the church. Conceived of as the voice of Utah’s women, and for many years the rare women’s publication west of the Mississippi, the eight-page, semimonthly periodical contained editorials, letters, articles, and poetry of interest to its predominantly female Mormon readers. From the very beginning, Emmeline B. Wells was a regular contributor.

Utah plays a special role in the history of woman suffrage. When it became a territory in 1870, women in this overwhelmingly Mormon settlement received the right to vote alongside men, making them among the tiny minority of nineteenth-century American women able to exercise the franchise. Mormon women were proud of their status as voters, and they took their rights of citizenship seriously. The inaugural issue of the Woman’s Exponent, published on June 1, 1872, prominently mentioned Susan B. Anthony on the first page.

That front page also mentioned in passing the “great outcry” raised against “the much marrying of the Latter-day Saints,” a reference to the controversial practice of celestial (or plural) marriage. The Woman’s Exponent was no antipolygamy screed. Its editors and readers unapologetically supported the right to practice polygamy, placing it in the same category as other women’s “rights” such as suffrage. Wells, who would be its editor for more than thirty-five years, was herself a plural wife. Hopes that Mormon women might use the vote to outlaw plural marriage proved totally unrealistic.

The “Mormon Question,” as it was widely called at the time, posed complicated challenges for the woman suffrage movement, which had to decide whether to embrace or disown polygamous Mormon women voters. More fundamentally, the constitutional question of whether Mormons should be legally allowed to practice polygamy went to the heart of the relation between law, morality, and religion in nineteenth-century America. As suffragists debated their relationship to Mormon women, they found themselves at the center of one of the most far-reaching political and legal questions of their times.

THE CALL for a mass meeting on Saturday, May 6, 1886, appeared in the leading Salt Lake City newspapers five days before the event was to be held. Addressed to “the ladies of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,” it boldly stated its purpose: “to protest against the indignities and insults heaped upon their sex” and “also against the disfranchisement of those who are innocent of breaking any law.” Having been voters since Utah became a territory in 1870, Mormon women now faced the prospect of being formally barred from the polls. Even more troubling, federal authorities had stepped up their campaign against polygamy, catching plural wives (the term preferred by Latter-day Saints) in the legal snare along with their polygamous husbands. Mormon women, deeply involved in political and religious life, were highly respected members of their communities, and they were not afraid to take a public stand in support of polygamy. In 1870, leading Mormon women staged an “indignation meeting” to protest congressional attempts to outlaw the practice. Now sixteen years later, they gathered to protest once again.1

The weather on the day of the mass meeting was “propitious,” and an eager crowd assembled in the portico and on the steps of the Salt Lake Theater. When the doors opened, nearly two thousand women—and a smattering of men—filled the theater to capacity. It was one of the largest gatherings of its kind ever convened in Utah Territory. This was no fringe group. The stage was filled with a cross-section of well-connected Mormon women, many of whom were married to leading figures in the church. After an opening prayer and a sampling of hymns sung by the Tabernacle Choir, fifteen women spoke to the assembled crowd. Nine additional talks, which could not be delivered because of time constraints, were later published along with correspondence from leaders who had been unable to attend in “Mormon” Women’s Protest: An Appeal for Freedom, Justice and Equal Rights.

The use of the colloquial term for their religion in the pamphlet title suggests that participants were well aware that their real audience was not the several thousand women jammed into the theater but the country as a whole, especially representatives in Washington, DC who held power over territorial affairs. A second intended audience was the national suffrage movement, which had a strong interest in protecting Utah women’s right to vote, even if suffrage leaders disagreed about the controversial issue of polygamy. The fact that woman suffrage, polygamy, and statehood were all intertwined reveals how complicated a seemingly straightforward issue like votes for women could be.2

The story of Mormon women’s politicization starts long before Utah women received the vote in 1870.3 The prophet Joseph Smith founded the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in upstate New York in 1830. From the start, his small band of followers faced distrust and persecution from the surrounding communities. Within ten years, they were forced to relocate to Nauvoo, Illinois. After Joseph Smith’s death in Nauvoo in 1844, Brigham Young led the followers to the arid desert of Utah, where they set about building a new society (Zion) from scratch. Already controversial as a new religion, the Mormons faced even more negative scrutiny after the church doctrine of celestial or plural marriage was officially announced in 1852, confirming the already widespread practice. Polygamy soon drew the attention of federal authorities, which passed various laws to challenge the practice, beginning in the 1860s. These laws proved unenforceable where Mormons were a firmly entrenched majority, but the issue became too politicized to disappear quietly.

Opposition to polygamy rested on both moral and legal grounds. In 1856, the Republican Party called slavery and polygamy the “twin relics of barbarism.” Once the Civil War settled the question of slavery, polygamy remained as a heinous moral stain on the country. Opponents could not imagine that women would willingly enter into such relationships—something Mormon women heartily disputed—and concluded they must have been coerced. Such marital despotism, which the popular press often compared to heathen harems, was presented as antithetical to monogamous Christian morality based on consent.4

Even if polygamy was seen as morally abhorrent, how to challenge it legally was a conundrum, because the regulation of domestic relations was traditionally a local or state concern. Furthermore, Mormons insisted the practice was a religious duty protected by the First Amendment. Polygamy in Utah thus presented a two-pronged challenge to the American legal system: Did the protection of religious freedom include the protection of polygamy? And in a federal system, which vested broad powers in local and state sovereignty, under what mandate could the federal government intercede in domestic affairs? As a constitutional conflict loomed, public antipathy towards polygamy hardened.

The 1886 mass meeting was a last-ditch attempt by Mormon women to mobilize national public opinion in support of the increasingly isolated and beleaguered Mormon minority. Nearly all of the speakers at the meeting were plural wives, and they presented themselves as upstanding community members who willingly accepted the tenets of celestial marriage as part of their religious faith.5 While it is clear that individual women often struggled with the daily challenges of family life with their sister-wives, they were not ashamed of the practice, and they publicly spoke in its favor. The women’s case for polygamy emphasized that it freed them from male lust while guaranteeing that all women would have the opportunity to marry and enjoy secure homes and respectable social positions. Turning public perceptions on their head, Mormons always claimed the high moral ground.6

At the mass meeting, Mormon women strongly challenged the widespread view that they were mere pawns of religious leaders or slaves to their husbands. “Hand in hand with Celestial Marriage is the elevation of women,” asserted Dr. Romania Pratt, a graduate of the Woman’s Medical College in Philadelphia and a plural wife. Dr. Ellis R. Shipp, another path-breaking female physician, concurred: “We are accused of being down-trodden and oppressed. We deny the charge!” As Mrs. Elizabeth Howard put it, “These are women that any nation should be proud of.”7

Mormon women were especially proud of what they had done with the vote, which Dr. Ellen Ferguson, answering another common charge, asserted had been deployed without “coercion or priestly dictation.” (Ferguson, an English immigrant who was probably the first woman physician in Utah, was the rare monogamist on the platform.) Demonstrating solidarity with their non-Mormon sisters, speakers found it especially galling that pending legislation would strip all Utah women, not just Mormons, of the vote. Needless to say, Mormon women hoped this threat would galvanize leaders of the national movement to intervene.8

The greatest indignation, however, was reserved for the federal authorities who were actively hunting down known polygamists and compelling their wives to testify against them, contravening longstanding common-law spousal protections. To Mormon women, these inquisitions, which included extremely intimate questions about the timing of sexual relations and the paternity of children, bordered on prurient intrusions into a private sphere no man should enter—certainly not law officials “who watch around our dooryards, peer into our bedroom windows, ply little children with questions about their parents, and, when hunting their human prey, burst into people’s domiciles and terrorize the innocent.” This affront to the dignity of their womanhood troubled them just as much as the loss of the vote did.9

Emmeline Wells was not able to attend the protest meeting, but she sent a carefully crafted letter of support from Chicago, calling the impending disfranchisement of Utah women “an act of despotism” and reminding the assembled sisters of the “greater liberty” and “equality of sex” of women in the Mormon Church.10 Because of her stature in the community and her frequent interactions with eastern suffragists, Wells was chosen along with Ellen Ferguson to journey to Washington, DC to present the Mormon women’s memorial to President Grover Cleveland, members of Congress, and other federal officials. Their appeal fell on deaf ears, as the Congress soon after passed the Edmunds-Tucker Act of 1887, which disfranchised all Utah women and confiscated Church property in an attempt to end polygamy. Even though she was now voteless after proudly exercising that right since 1870, Emmeline Wells was still a suffragist, and she redoubled her efforts to win back the vote for all her Utah sisters, not just the Mormon ones.

The decades-long suffrage activism of Emmeline Wells provides a window into the complex interplay between suffrage and polygamy in Utah and the nation at large. Born Emmeline Blanchard Woodward in Petersham, Massachusetts in 1828, she converted at the age of fourteen after her mother joined the church. The next year she married the son of a local Mormon leader. The young couple joined the exodus to Nauvoo in 1844, and, in a short space of time, she gave birth to a son who died and her teenage husband abandoned her. In 1845, she became the plural wife of Bishop Newel Whitney, who was thirty-three years her senior. In what seems to have been a loving and supportive relationship, she had two daughters with him before he died in 1850. By then she was living in Salt Lake City.11

In 1852, she entered into another plural marriage (her husband’s seventh and final) with Daniel H. Wells, a counselor to Brigham Young and later the mayor of Salt Lake City, with whom she had three additional daughters. This marriage gave her social standing and allowed her to embark on something approaching a public career. Her first position was as the private secretary to Eliza R. Snow, a plural wife of founder Joseph Smith who, after his death, became a plural wife of his successor Brigham Young. Snow was president of the Relief Society, the most influential leadership role available to women in the Mormon community.

When the Woman’s Exponent was founded in 1872, Wells became a regular contributor. In 1877, she took over as editor, a position she held until the periodical ceased publication in 1914. The masthead of the Woman’s Exponent stated “The Rights of the Women of Zion, and the Rights of the Women of all Nations,” and Wells’s goals for the publication were similarly expansive: Mormon women “should be the best-informed of any women on the face of the earth, not only upon our own principles and doctrines but on all general subjects.” In turn, her editorship of the publication enhanced her national stature, providing an important credential when she dealt with eastern suffragists.12

When territorial Utah women unexpectedly won the vote in 1870, the two national suffrage organizations took note. The groups had recently split over whether to support universal manhood suffrage or focus on securing the ballot for women; Mormon women and polygamy became another issue fundamentally dividing the two groups.

Since the vast majority of Utah voters were Mormons, it proved impossible to separate the issue of polygamy from suffrage. Lucy Stone and her more conservative American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) distanced themselves completely from polygamous Mormon women, while Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony took a different tack, welcoming them into the fold of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). Thus began a complicated tango within the suffrage movement lasting two decades, with one wing gingerly acknowledging Mormon women as allies while the other emphatically refused to have anything to do with them.

Curious about the recent turn of events in Utah, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony took advantage of the newly opened transcontinental railroad in 1871 to visit Salt Lake City on their way to California. During their weeklong stay, they juggled rival Mormon factions while also showing their support for Utah’s newest voters. Stanton’s views on topics such as birth control proved too radical for the Mormons, but Anthony became a much admired figure despite her personal abhorrence of polygamy. She earned this respect with her willingness to work with Mormon woman suffragists on their own terms, regardless of their status as plural wives. If they supported woman suffrage, that was all that mattered. Stanton’s and Anthony’s openness to a variety of differing viewpoints was a clear contrast to the AWSA’s more cautious approach, but it had its costs. The hot-button issue of polygamy increasingly became a liability that threatened to outweigh the benefits of embracing these newly enfranchised voters.13

In the 1870s, however, things were a bit more fluid. This worked to the benefit of Mormon woman suffragists, who wanted to enhance their legitimacy through affiliation with the national movement and challenge the unflattering stereotypes of Mormon women held by many American citizens. They also hoped to build political support for eventual statehood, which would keep woman suffrage intact. In 1877, Emmeline Wells took the lead in organizing Utah women in support of a proposed sixteenth amendment (woman suffrage) to the Constitution by collecting thousands of petition signatures as well as securing financial support from the LDS leadership. Her activism earned her a spot as a representative of Utah on the NWSA board. She was the first Mormon so recognized. In 1879, she and Zina Young Williams, Brigham Young’s daughter, journeyed to Washington, DC, where Wells addressed NWSA’s national convention.

But such prominence on the national stage was short-lived. The political climate, never very supportive, turned more sharply against polygamy after a definitive Supreme Court decision in 1879 ruled that Mormons did not have a constitutional right to practice a form of marriage expressly prohibited by Congress as a violation of public morality. The Edmunds Act of 1882 offered more sanctions against the practice in the territory, a process completed by the Edmunds-Tucker Act of 1887. As early as 1884, even the NWSA was distancing itself from Mormon women, focusing instead on trying to keep the ballot for non-Mormon and non-polygamous women. That year, Emmeline Wells was quietly dropped from the NWSA national masthead.

For the Mormon community, 1890 was a “year of shocks.” Mormon leaders, desirous of statehood and the legitimacy it would convey, recognized the futility of fighting for the right to practice polygamy, and they officially renounced the practice. (Whether it would continue informally was another matter.) Among other things, removing the issue of polygamy in Utah helped pave the way for Susan B. Anthony’s initiatives to reunite the two wings of the suffrage movement, and in 1890, the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was formed.14

Even before the formal abandonment of polygamy, Mormon suffragists quietly began to put forward only monogamous (or “innocent”) women as delegates to national conventions. For example, Emily Richards, the monogamist wife of a prominent Mormon lawyer based in Washington, DC, was chosen to address the inaugural gathering of the International Council of Women in the nation’s capital in 1888, while Emmeline Wells sat the conference out. And in January 1889, when the Utah Woman Suffrage Association was formed, an informal understanding that no one who had “ever been in plural marriage” could hold a leadership position sidelined Wells. While she realized the political necessity of the decision, it was undoubtedly painful.15

When Wyoming officially became a state in 1890, it provided the first star for the suffrage flag, followed by Colorado in 1893 and then Utah and Idaho in 1896. When Utah’s suffragists attended the 1896 NAWSA convention, they were welcomed as heroes. But only four Utah women made the trip. The day the delegation left for Washington, Emmeline Wells could “scarcely believe” that she was not going with them. In the end, despite all she had done to make woman suffrage a reality, she could not raise the necessary funds to pay her way.16

In retrospect, participation in the national suffrage movement in the 1880s and 1890s represented a high point of political activism among Mormon women. Their twin goals of suffrage and statehood achieved, Mormon women moved warily into electoral and partisan politics, but they found the terrain challenging. Other newly enfranchised female voters across the country shared the sentiment. As the first generation of Utah Mormons died out, and as more time elapsed since the heroic early efforts of both sexes to make the Utah experiment viable, Mormon women’s activity in national politics continued, at least through the Progressive era, but with diminishing support from the LDS leadership for their participation in active public roles. This conservative thrust greatly intensified as the rest of the twentieth century unfolded, and Mormon women’s activism on behalf of the vote was quickly forgotten.

The centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment offers a chance to write these Mormon women back into history. Mormon suffragists were highly politicized actors. They knew how to organize mass meetings, gather petitions, raise money, and lobby politicians and church leaders. Far from the popular image of downtrodden women degraded by polygamy, these proud and committed suffragists saw no conflict between their religious beliefs and their activism on behalf of their sex. In fact, they felt privileged to be part of a community which took women so seriously. Mormon women deserve to be part of suffrage history both on their own merits and also because their peculiar situation helps explain the wide divisions that kept the national suffrage movement divided until 1890.

While suffrage leaders consciously distanced themselves from their earlier controversial associations as they maneuvered the movement into the political mainstream after 1890, the lingering effects of the battle played out in national political life. The antisuffrage movement recycled ideas from the antipolygamy campaign, especially the argument that giving women the vote was an attack on traditional marriage and the family. There are strong parallels between the antipolygamy campaign and the efforts to restrict Chinese immigration. The language describing Chinese prostitutes as degraded and akin to slaves, for instance, was very similar to earlier descriptions of Mormon women under polygamy, putting both groups on the outside as “others.” In legislation like the Dawes Act of 1887, which mandated a system of land allotment based on individual families rather than tribes, Native Americans were pressured, as Mormons had been, to conform to Protestant views of marriage and family life. Far from an interesting anomaly in the suffrage story, polygamy remains a surprisingly central aspect of late-nineteenth-century political history.

Emmeline Wells’s contributions to Mormon life and the suffrage movement were far from over when polygamy officially ended. Widowed in 1891—and thus technically no longer a plural wife—she attended the 1891 NAWSA convention as a delegate-at-large. In 1899, Wells delivered a speech to the International Council of Women in London on “The History and Purposes of the Mormon Relief Society,” and the next year she and other Mormon suffragists presented Susan B. Anthony with a bolt of black silk brocade made in Utah for her eightieth birthday. In 1910, Wells became the fifth president of the Relief Society, the prestigious welfare and relief organization most closely associated with women’s empowerment in the church. When she turned ninety, she was celebrated with a festive event at the Hotel Utah, and two years later, more than a thousand people attended her ninety-second birthday party.

Emmeline Wells didn’t have to wait for the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to cast her first vote. Except for a short interval, she had been voting regularly since 1870, making her one of the longest-voting women of her era. But she managed to live to see the Nineteenth Amendment’s adoption. She died in 1921 at age ninety-three, after a lifetime of activism on behalf of women and her Mormon faith, a gentle but forceful reminder that those two causes have not always been in fundamental opposition.

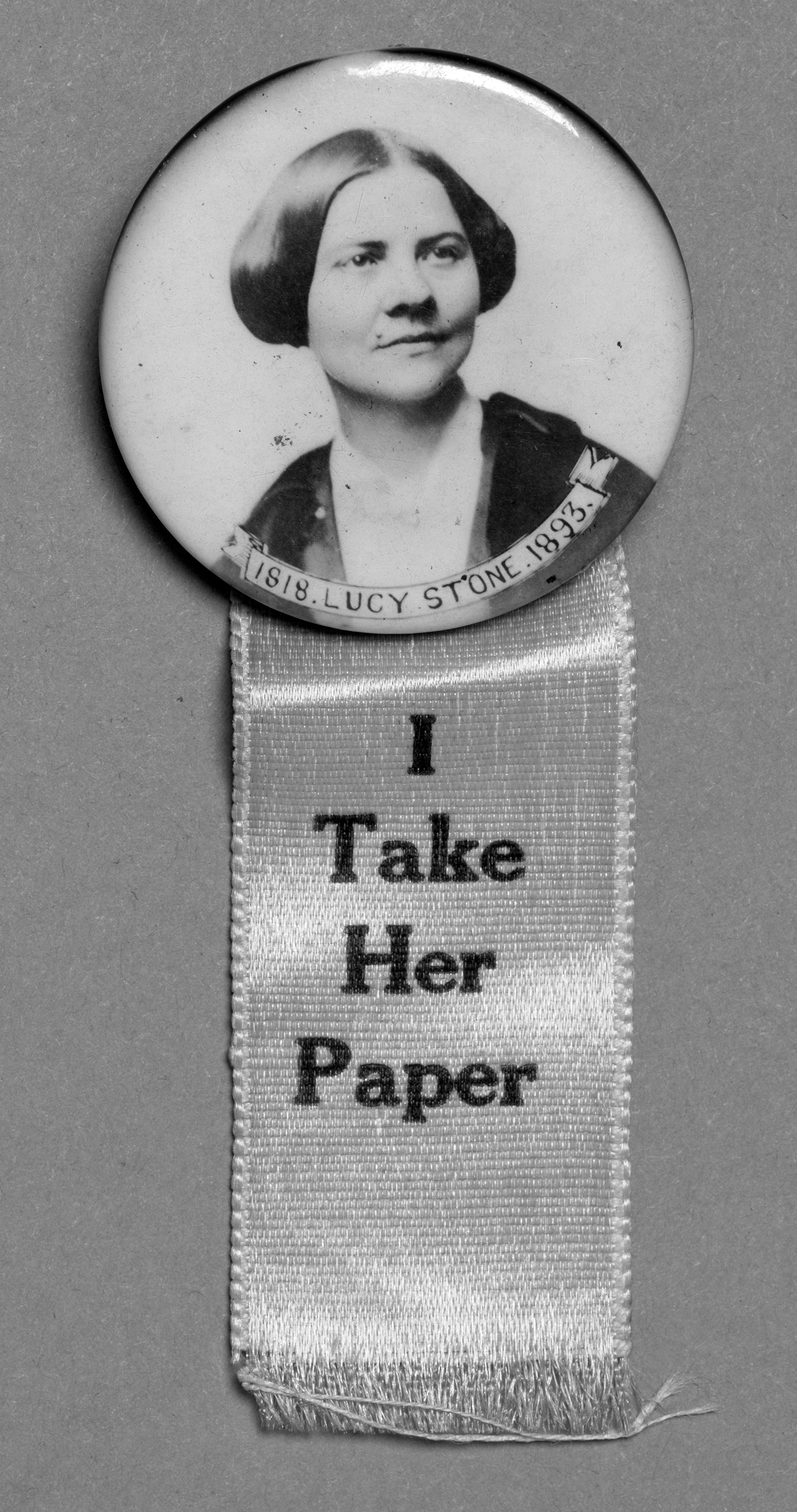

Woman’s Journal button with portrait of Lucy Stone (1818–1893). Courtesy of Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.