CHAPTER SIX

The Shadow of the Confederacy

NEW ORLEANS was a popular spot for conventions in 1903. In May, tens of thousands of former Confederate soldiers and their families from all over the South descended on the city for the annual gathering of the United Confederate Veterans, an organization formed in that same city in 1889. One of them was Alexander Green Beauchamp, a veteran from Mississippi who had served under General Nathan Bedford Forrest before being taken prisoner by Union forces at the battle of Selma on April 2, 1865. His badge identifying the outfit with which he served became a treasured family memento. It arrived at the Schlesinger Library by way of marriage: Beauchamp’s grandson Joseph Howorth married Lucy Somerville, a fellow lawyer and the daughter of Nellie Nugent Somerville, a noted Mississippi suffragist and NAWSA official.

In an odd quirk of history, Nellie Nugent Somerville had likely been in New Orleans just two months earlier than Beauchamp, attending the National American Woman Suffrage Association convention in March. The gathering, orchestrated by the Louisiana suffragists (and rabid white supremacists) Kate and Jean Gordon, was profoundly shaped by its southern setting. It was only the second time that the national convention was held in the South; Atlanta in 1895 had been the first.

Bowing to local prejudice, African American women were barred from all convention proceedings. Worse still, NAWSA adopted an official policy statement in New Orleans that allowed individual state organizations to determine their own standards for membership and “the terms upon which the extension of suffrage to women shall be requested.” In other words, NAWSA caved to prevailing racism by endorsing a states’ rights policy that gave southern suffrage groups free rein to exclude African American women. NAWSA’s new policy also emboldened southern suffragists to deploy arguments that bolstered white supremacy and the exclusion of African Americans from public life, such as claiming that enfranchising white women would offset the votes of African American men. It was not the suffrage movement’s finest hour.

Juxtaposing these two conventions—the United Confederate Veterans and NAWSA—held in the same year in the same southern city reminds us of how deeply and powerfully the legacy of the Civil War shaped southern politics and public life even fifty years after Appomattox. For many southerners, the war never really ended; upholding the “lost cause” was an ongoing source of pride and civic duty. That was the unfriendly terrain on which white southern suffragists labored.

WHEN MARY JOHNSTON’S suffrage novel Hagar appeared in 1913, it caused quite a stir. Set in a small backwater of rural Virginia, it offered a fictional account of scenes that could have played out in actual households across the South. The chapter “A Difference of Opinion” opens with a character named Colonel Ashendyne discovering a letter stamped “Votes for Women.” “How do you happen to get letters like that?” he challenges his granddaughter Hagar.

Confederate Army reunion pin and ribbon, 1903. Courtesy of Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

“Why not?” she replies. “I propose presently actively to work for it myself.”

Her grandfather reacts to that statement with “apoplectic silence,” leaving her grandmother to put into words what both are thinking: “Women Righters and Abolitionists!—doing their best to drench the country with blood, kill our people and bring the carpetbaggers upon us!” Then comes an ultimatum from the family patriarch: “Either you retire from such a position and such activities, or you cease to be granddaughter of mine.”1

What was a New Woman—and a southern one at that—to do? At first Hagar feels trapped, but “then she realized she was not trapped, and she smiled.” She is a successful writer—“good for something more than ten thousand a year”—and she is economically independent. She doesn’t have to go along with her family’s conservative ideas about woman’s place in southern society. She could instead embrace her “Fourth Dimension”: “inner freedom, ability to work, personal independence, courage and sense of humour and a sanguine mind, breadth and height of vision, tenderness and hope.” Within days, Hagar is on her way back to New York City.2

Totally forgotten today, Mary Johnston was one of the country’s most popular turn-of-the-century writers, often mentioned in the same breath as Sir Walter Scott and Tolstoy. To Have and To Hold, a historical romance set in colonial Jamestown, was the nation’s bestselling novel in 1900, selling close to half a million copies. Johnston followed it with a string of historical novels, including two deeply researched bestsellers about Virginia in the Civil War: The Long Roll (1911) and Cease Firing (1912). Margaret Mitchell, no slouch herself when it came to writing about the conflict, later confessed, “I felt so childish and presumptuous for even trying to write about that period when she had done it so beautifully, so powerfully—better than anyone can ever do it, no matter how hard they try.” Alas, Johnston’s suffrage novel failed to capture the reading public’s attention, and it did not earn back its $10,000 advance.3

“No stronger characters did the long struggle produce than those great-souled Southern suffragists. They had need to be great of soul.” That assessment by Carrie Chapman Catt and Nettie Shuler certainly applies to Mary Johnston. She was born in 1870 in the small town of Buchanan, Virginia, “a Southern aristocrat, raised in a climate of reverence for the Confederacy.” She was the oldest of John William Johnston’s and Elizabeth Dixon Alexander Johnson’s six children. John William Johnston was a railroad executive who had been a major in the Confederate artillery; his family tree included Joseph E. Johnston, a Confederate general under whom Elizabeth’s father served at Vicksburg. “We lived in a veritable battle cloud, an atmosphere of war stories, of continued reference to the men and the deeds of that gigantic struggle,” Mary Johnston wrote, and she drew on that family history as inspiration and background for several of her novels.4 She even made her father an actual character in Cease Firing.

Johnston’s twenties were a combination of crisis and opportunity. When she was nineteen, her mother died, and Mary assumed responsibility for her younger siblings. The next year, she accompanied her father on a European tour. This pattern of exposure to ideas and people outside the South influenced both her personality and her writing, as did her father’s financial reverses in 1895. “We were living comfortably in an easy Southern fashion in New York,” she remembered. “In a week all was changed. There was a sharp need of retrenchment and even when retrenchment was accomplished, need remained.” Without telling anyone of her plans, she began writing the historical novel which became Prisoners of Hope, a love story / political intrigue set in mid-seventeenth century Virginia that Houghton Mifflin published to positive reviews in 1898.5

The launch of Johnston’s literary career coincided with a revival of popular interest in large-scale historical romances and adventures. Her next book, To Have and To Hold, set in Jamestown in 1622, recounted a love story, between a recent settler and a disguised lady-in-waiting, in the midst of an Indian uprising. The prestigious Atlantic Monthly published the chapters serially from June 1899 to March 1900—quite an accomplishment for an author’s second book. The serialization created such a buzz that sixty thousand advance copies of the book were sold, and it sold 135,000 more in the first week after publication. That burst of sales earned Johnston a sizeable $50,000, and additional sales would increase her take to $70,000. To Have and To Hold remains Johnston’s best-known work.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, the author the New York Times referred to as a “high-bred aristocratic girl of the South” found both critical success and a large popular audience for her novels, including Audrey (1902), a melodrama which took place in eighteenth-century Virginia, and Lewis Rand (1908), a tale of ambition and intrigue set in the early republic. Her first nine books earned over $200,000, which allowed her to support herself and take care of her family after her father’s death in 1905. In 1911, Johnston, who never married, bought forty acres of land in the resort area of Bath County, Virginia, outside the town of Warm Springs. She commissioned a grand twenty-room Italian Renaissance house with a Colonial Revival interior, as well as cottages for two of her sisters, who also never married. Johnston lived at Three Hills for the rest of her life.6

Mary Johnston first expressed public support for the suffrage movement in a 1909 newspaper interview. Such an endorsement from a well-known literary celebrity was quite a boost for the cause. Three weeks later, she, her friend and fellow writer Ellen Glasgow, and the social activist Lila Meade Valentine—“some of the best people of Virginia”—founded the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia, based in Richmond. Reflecting how retarded suffrage activism was in the South as compared to the nation at large, the Equal Suffrage League marked the first viable suffrage association in the state.7

For the next six years, Johnston was actively involved in the suffrage cause. With her impeccable southern pedigree always proudly on display, she wrote articles, gave speeches, and lobbied and testified before the Virginia legislature. She even took elocution lessons to improve her public speaking, a meaningful commitment for a writer who had not previously associated herself with any political causes. In addition to her suffrage advocacy, she also expressed support for the labor movement and privately identified as a socialist. She declined, however, to speak publicly for those causes, for fear of damaging support for suffrage, which was already controversial enough in her native state.

Mary Johnston laid out her emerging ideology in an April 1910 article in the Atlantic Monthly. She called the movement “The Woman’s War”—a telling phrase from someone so steeped in Confederate history—and noted at the outset the difficulties it faced in her state. “Virginia, if the dearest of states, is also the most conservative. Her men are chivalric, her women domestic.… She makes progress, too, but her eyes are apt to turn to the past.” Such conservatism explained “the shock of surprise, or more or less indignant incredulity” that greeted the Richmond women’s decision to ask for the vote. As Johnston noted, “in the South we are not used to woman’s speaking—not, certainly, on the present subject.”8

When Johnston published that piece, she was deeply immersed in the research for her Civil War novels, which would come out in 1911 and 1912. When a reporter trying to find an angle from the publicity-shy author asked her if she was going to write a book on suffrage, she demurred, but clearly it was on her mind. Yet a narrative set in the present—a first for her—and dedicated to a controversial idea posed quite different challenges than her earlier historical novels had.9

The eponymously named Hagar tells the story of Hagar Ashendyne, a product of the Old South who grows up to be a New Woman. Just as memories of the Civil War shaped southern life, so does the novel reflect the legacy of slave life on the plantation, albeit indirectly. Hagar’s ancestral home, Gilead Balm, draws its name from the well-known Negro spiritual “There is a balm in Gilead.” More pointedly, the main character shares a name with a Biblical character who has long been associated with the suffering of enslaved women. Hagar is the Egyptian slave of Sarah, who offers her to her husband Abraham as his concubine. Later Hagar and her son Ishmael are cast out, wandering in the wilderness until God comes to their rescue. These biblical allusions were well known to Johnston’s readers.10

Hagar is twelve and already something of a free spirit when the novel begins. She has a decidedly unconventional family situation. Her artist father is roaming around Europe, having left his bedridden wife Maria at home with his parents at their Virginia plantation. Maria suffers from nervous prostration and soon dies. Hagar eventually reunites with her father, whose second marriage to a wealthy widow ends with the widow’s drowning and his being left a cripple. The two of them spend much of her twenties traveling throughout Europe and South America together.

Edmonia Lewis, the first woman of mixed African American and Native American heritage to win acclaim as a sculptor, created this white marble statue of the enslaved woman Hagar in 1866. Mary Johnston also drew inspiration from that biblical character as the name of the white protagonist of her suffrage novel. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC / Art Resource, NY.

By now Hagar has become a successful novelist. Her travels bring her into contact with new people and new ideas, and she embraces a far broader view of women’s roles than she had been brought up with in the conservative South. At the very top of her list is a commitment to women’s economic independence, a key factor in her desire to become a writer. While she never abandons her roots in Gilead Balm, she feels most at home living on her own in New York City, where she gets involved in the socialist movement, settlement work, and the suffrage movement. That involvement sets up the “difference of opinion” confrontation with her kinfolk back home, but she does not back down. Having rejected various suitors along the way, at the end she meets a bridge builder named John Fay, who accepts her as the liberated woman she is and still wants to marry her. She in turn surprises him—and the reader—by saying she would like to have children. The novel ends with them walking hand-in-hand back from a beach where they have almost drowned in a storm.

For a work that is usually referred to as a suffrage novel, Hagar doesn’t really devote much plot time to the issue—only the last seventy-five pages of an almost four-hundred-page book. But the novel is very much in the spirit of the wide range of pro-suffrage literature—short stories, plays, poetry, novellas, autobiographies, and journalistic sketches, as well as novels—produced over the course of the long struggle. The novel most readily associated in the popular mind with women’s rights was Henry James’s The Bostonians (1886), with its hostile portrait of Verena Tarrant, Olive Chancellor, and Basil Ransom, but far more sympathetic treatments appeared in novels such as Edna Ferber’s Fanny Herself (1917), Gertrude Atherton’s Julia France and Her Times (1912), Zona Gale’s Mothers to Men (1911), and Alice Duer Miller’s Are Women People? (1915). Popular literary works proved a handy way to broadcast the ideas of the suffrage movement to a general audience.11

Like Oreola Williams Haskell’s Banner Bearers, what mainly comes through in Johnston’s novel is Hagar’s unequivocal belief in the justice of the cause and her delight at sharing the camaraderie of the movement dedicated to winning it. In the end, Hagar is as much a general plea for women’s emancipation as a suffrage tract. In order for women like Hagar to grow and prosper, the old values of the South must give way to more modern views that include political equality and much more.

Johnston’s evolutionary approach to social progress clearly owes a large debt to Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Women and Economics (1898). In fact, Gilman and Johnston were friends. Gilman’s description of Johnston’s doubleness perfectly captures how the writer used the façade of a genteel southern lady to slip powerful ideas by her often unsuspecting audience. “You fascinating person,” Gilman wrote her friend. “You always make me think of an eagle, delicately masquerading as a thrush—so soft and gentle and kind—and with big sweepingness in back of it all.” Gilman was especially impressed by what Johnston had accomplished in Hagar: “I feel as if, having established your high reputation in historical novels, you were now doing far better and bigger work. People won’t like it as well, of course, but keep on.”12

Like all of Johnston’s novels, Hagar was widely reviewed, but critics were split. While some cheered her decision to write a present-day story dealing with contemporary issues, many more found the result little more than unsatisfying propaganda. For example, Helen Bullis’s review in the New York Times called it “a very pleasant story” but noted that it began to “sag” when if left Hagar’s childhood. The reviewer gave Johnston credit for her convincing depiction of suffrage as hard work, “but we would remind Miss Johnston that it is not novel writing. The novel reader ‘must be shown’—he resents being told.” Literary criticism ever since has generally agreed that this book was not among her best. But when it’s read as a window on the New Southern Woman circa 1913, the book has much to offer.13

Hagar and Mary Johnston offer an interesting perspective on the southern suffrage movement, which encountered steep resistance throughout its duration. So revered was the cultural ideal of the southern lady, the embodiment of the region’s hierarchical and patriarchal way of life rooted in slavery and its aftermath, that any attempt to change gender roles was seen as a threat to southern womanhood, the home, and white supremacy. To the vast majority of southerners, suffrage advocacy was yet another dangerous idea promoted by outsiders—that is, northerners—in a region still smarting from the Civil War and the Reconstruction experiment that followed.14

Despite such odds, a determined cadre of southern suffragists began to speak up. Like Mary Johnston, many of them traced their pedigrees to the southern elite. “The truth was,” according to the historian Marjorie Spruill Wheeler, “only southern women of Johnston’s type, rearing, and environment could violate social convention so thoroughly and get away with it, and thus, with very few exceptions, the leaders of the southern suffrage movement were drawn from the region’s social and economic elite.” Imbued with a strong sense of noblesse oblige, they were dismayed by the politicians who dominated the South when Reconstruction ended. Women like Laura Clay of Kentucky, Kate Gordon of Louisiana, Belle Kearney and Nellie Nugent Somerville of Mississippi, and Rebecca Latimer Felton of Georgia wanted to raise the standards of public life, and they quickly realized they needed the ballot to have an impact. But although suffrage organizations appeared throughout the South, and although southern suffragists played significant roles in NAWSA, especially in the 1890s, every suffrage campaign in a southern state was defeated.15

Southern suffrage was always very much tied up with race. Even after the end of Reconstruction in 1877, southerners feared that the federal government might enforce the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments more aggressively. This fear provided an opening wedge, albeit a racist one, for the suffrage movement to take root in the 1890s: enfranchising white women, they argued, would offset votes by black men. By the turn of the century, however, southern states had figured out how to keep black voters from the polls through other means, so this argument became less compelling. For the first decade of the twentieth century, the movement went dormant.

Starting around 1909, things picked up again in various southern states. Since black men had been effectively disfranchised by then, there was less need to portray woman suffrage as a cornerstone of white supremacy. But a new challenge appeared as the national movement increasingly coalesced around a federal amendment. Southern states’ rights advocates recoiled, dismayed at the prospect of the federal government intervening yet again in what they saw as a state and local matter. In the end, most southern suffragists drifted towards support of NAWSA’s “Winning Plan,” but support for a federal amendment was still an uphill battle. Only four southern states (Texas, Arkansas, Kentucky, and Tennessee) voted to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment. Virginia didn’t officially do so until 1952.

Much attention has focused on the racism of southern suffragists and their strategies, and there is no denying that race was often explicitly deployed in ways harmful to African American rights. Such explicit playing of the race card goes beyond the generalized racism that plagued the entire movement. Much of the worst race baiting occurred in the 1890s, and it was much less prevalent after 1910. Suffrage leaders in the various states displayed a definite range of attitudes on race and white supremacy. On the one extreme was Kate Gordon of Louisiana, who was one of the most egregious at playing the race card. Belle Kearney of Mississippi, who gave the keynote address at the 1903 convention, was also outspoken in her defense of Anglo-Saxon purity.16

At the other end of the spectrum was Mary Johnston, who showed—within the limits of being a white southern woman of a certain class and mindset—much more restraint when it came to questions of race, both in terms of her suffrage advocacy and her writing. Johnston’s novels are relatively free of demeaning stereotypes and portrayals of black southern folk, yet this support only went so far: Johnston never publicly spoke out against the widespread disfranchisement of black voters. Only after suffrage was won did Johnston tackle touchy subjects like slavery or lynching in her writing.17

Even so, Johnston brought an unusual sensibility about race to her suffrage work. When contemplating the question of property qualifications for voting, she cautioned, “I think that as women we should be most prayerfully careful lest, in the future, that women—whether colored women or white women who are merely poor, should be able to say that we had betrayed their interests and excluded them from freedom.” When Kate Gordon’s antiblack rhetoric became too toxic in the Southern States Woman Suffrage Council, a group dedicated to pushing for state suffrage amendments rather than a federal amendment, Johnston quietly resigned in 1915. She did not participate in the final push for suffrage, or the ratification battle. Instead, she turned her attention back to her writing.18

Hagar marked something of a turning point for Mary Johnston. In addition to her newfound political engagement, she also became increasingly interested in mysticism, which she incorporated in her later novels. Each time she changed her style and focus, however, she lost more readers than she added, which affected both her popularity and her earning power. When she tried to rekindle her old affinity for historical adventure in the 1920s, she found herself preaching to an increasingly small core of dedicated followers in changed literary times. Her books never again became bestsellers.

Mary Johnston always took the long view, about both her writing and her advocacy for women’s emancipation. “I am an educated and intelligent woman, and I cannot understand how it is possible for an intelligent woman not be interested in a question of such worldwide importance not only to the women but to the race, a reform so necessary and vital. The race cannot be emancipated until all its members are emancipated,” she told the New York Times in 1911. Even though suffrage was a hard sell in her native South, Johnston was sure it would prevail. “The Southern woman has pride,—Oh she has pride! … [and] when it comes to her aid, she will become a suffragist.”19

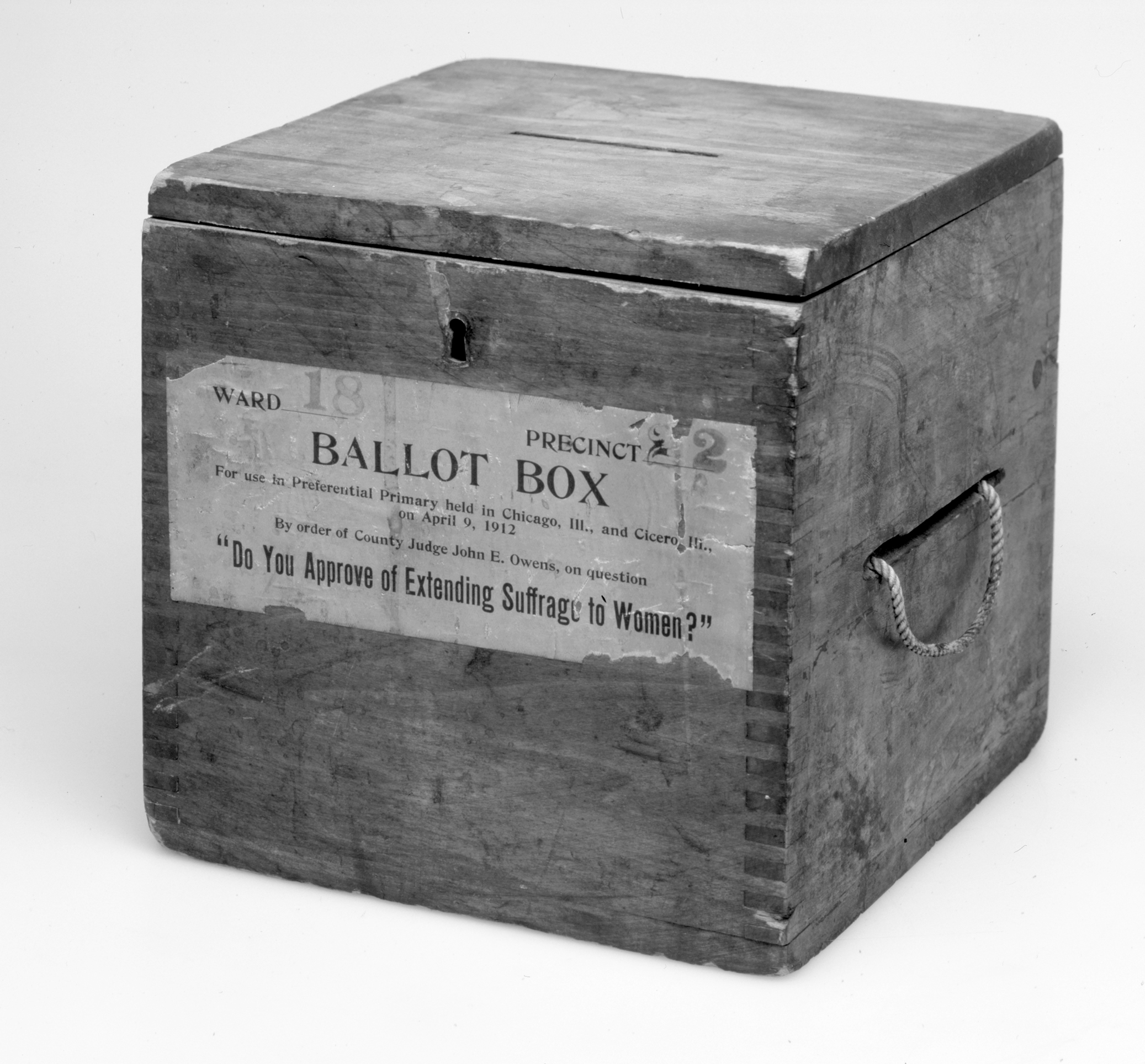

Ballot box from a special primary held in Chicago and Cicero, Illinois on April 9, 1912. Courtesy of Chicago History Museum.