Chapter 9

Determining the Cause and Manner of Death: Forensic Autopsies

IN THIS CHAPTER

Introducing death: Its causes, manners, and mechanisms

Introducing death: Its causes, manners, and mechanisms

Understanding the role of a forensic pathologist

Understanding the role of a forensic pathologist

Digging in to a forensic autopsy, step by step

Digging in to a forensic autopsy, step by step

Summing up the findings in an autopsy report

Summing up the findings in an autopsy report

The dead do “talk,” but only figuratively. Changes that take place in the body before and after death reveal which diseases victims suffered, what trauma they endured, which toxins were present at the time of death, and much more. Autopsy, or examining a corpse to determine how death occurred, is the method used to interpret exactly what a body says.

Defining Death and Declaring It as Such

Picture yourself being buried alive. People living prior to the nineteenth century had good reason to worry about such matters, because stethoscopes hadn’t been invented, and determinations of death were more a guessing game than a scientific pursuit. A weak heartbeat meant you’d probably be pronounced dead — only to wake up while your body was being prepared for burial. Fortunately, those days are gone, but plenty of trial and error took place before they could be laid to rest.

Searching for a definitive method

Determining death never has been straightforward. Alcohol, drugs, heart attacks, serious infections, bleeding, shock, dehydration, and other situations can render supposed victims comatose, cold to the touch, and with weak respiration and pulse, and they might appear dead when in fact they aren’t.

- Tongue and nipple pulling

- Tobacco smoke enemas

- Insertion of hot pokers into various bodily orifices

If a person on a ventilator was shot in the head, hit by a drunk driver, or otherwise ended up in that condition as a result of suspicious means, determining death becomes an issue for the coroner or medical examiner. Charges that can be filed against the shooter, driver, or other perpetrator become measurably more serious if the victim dies. Before physicians caring for the victim actually pull the plug on the ventilator, they must be absolutely sure the victim has no hope for survival. Otherwise, doctors can be implicated in the death.

Determining the causes and mechanisms of death

A gunshot to the heart, for example, is a cause of death that can lead to one of several mechanisms of death, including cessation of the heartbeat (cardiac arrest), exsanguination (bleeding to death), or sepsis (infection that enters the bloodstream). Similarly, the victim of blunt force head trauma can die from direct trauma to the brain (cerebral contusion), bleeding into the brain itself (an intracerebral bleed), or bleeding around the brain (a subdural or epidural hematoma), all of which can lead to compression of the brain and result in a stoppage of breathing (asphyxia). Again, one cause can lead to death by several mechanisms.

Conversely, one mechanism can result from several different causes. A gunshot wound, stabbing, bleeding ulcer, or a bleeding lung tumor can cause you to bleed to death. In each case, blood loss and shock are the abnormal physiological changes.

In cases in which the mechanism of death is unclear, the medical examiner or coroner (see Chapter 2) assesses the evidence to determine the true cause and mechanism of death, which can impact what criminal or civil actions follow, if any.

Uncovering the four manners of death

The manner of death is the root cause of the sequence of events that leads to death. In other words, it answers these questions:

- How and why did these events take place?

- Who or what initiated the events and with what intention?

- Was the death caused by the victim, another person, an unfortunate occurrence, or Mother Nature?

- Natural: Natural deaths are the workings of Mother Nature in that death results from a natural disease process. Heart attacks, cancers, pneumonias, and strokes are common natural causes of death. Natural death is by far the largest category of death that the ME sees, making up over half of the cases investigated.

- Accidental: Accidental deaths result from an unplanned and unforeseeable sequence of events. Falls, automobile accidents, and in-home electrocutions are examples of accidental deaths.

- Suicidal: Suicides are deaths caused by the dead person’s own hand. Intentional, self-inflicted gunshot wounds, drug overdoses, and self-hangings are suicidal deaths.

- Homicidal: Homicides are deaths that occur by the hand of someone other than the dead person.

- Undetermined or unclassified: These are deaths in which the ME can’t accurately determine the appropriate category.

Just as causes of death can lead to many different mechanisms of death, any cause of death can have several different manners of death. A gunshot wound to the head can’t be a natural death, but it can be deemed homicidal, suicidal, or accidental.

Though the ME can usually determine the manner of death, it’s not always easy, or even possible. For example, the manner of death of a drug abuser who overdoses is most likely to be either accidental or suicidal (it also could be homicidal, but it’s never natural). When the cause of death is a drug overdose, autopsy and laboratory findings are the same regardless of the victim’s or another’s intent. That is, the ME’s findings are the same whether the victim miscalculated the dose (accidental), intentionally took too much (suicidal), or was given a lethal dose (homicidal). For example, perhaps the victim’s dealer, thinking the user had snitched to the police, gave the victim a purer form of heroin than he was accustomed to receiving, so that his “usual” injection contained four or five times more drug than the unfortunate soul expected. Simply put, no certain way exists for determining whether the person overdosed accidentally, purposefully, or as the result of another’s actions. For these reasons, such deaths are often listed as Undetermined.

Death from a heart attack because of an error during surgery is another example of a “natural” death that isn’t natural. Although heart attack is a natural cause of death, the manner by which the heart attack occurred could be deemed accidental (often euphemistically termed a “medical misadventure”) and malpractice litigation could follow. Likewise, a person with severe heart disease might be assaulted on the street, and, while struggling with the assailant, could suffer a heart attack and die. The cause of death again is a heart attack, but the manner could be deemed homicidal.

Shadowing the Forensic Pathologist

As you may suspect, determining the cause, mechanism, and manner of death takes a thorough knowledge of the ins and outs of human biology. Autopsies therefore should be performed by pathologists, medical doctors who specialize in determining how disease affects the body.

The forensic pathologist is concerned with the study of medicine as it relates to the application of the law and, in particular, criminal law. Furthermore, the forensic pathologist is more likely to deal with injuries. Nevertheless, more than 50 percent of the cases he deals with involve death caused by disease. He performs the kind of autopsies (forensic) that produce evidence that often must be presented as testimony in court as the findings and opinions of an expert. Find out more about expert testimony in Chapter 1.

Discovering what makes an autopsy forensic

Forensic pathologists typically perform medical-legal autopsies, although in some areas, hospital pathologists may be designated medical examiners and charged with this duty. And in some jurisdictions, the local undertaker performs the autopsies, even though he isn’t trained in forensic pathology.

A medical autopsy is conducted to determine the medical factors relating to death and to search for any illnesses the deceased may have suffered. The forensic autopsy, on the other hand, is performed initially to determine not only the cause of death and any illnesses the deceased had, but also the time, mechanism, and manner of death.

Deciding who gets autopsied

The ME typically investigates any death that is

- Traumatic: Occurring from an injury that could be accidental, homicidal, or self-inflicted

- Unusual: Occurring in circumstances that appear to be unnatural or suspicious

- Sudden: Taking place within a few hours of the onset of symptoms

- Unexpected: Occurring in someone who wasn’t thought to be ill

The terms reportable death and coroner’s case refer to any death that must be referred to the coroner or ME for investigation. Circumstances that constitute a reportable death vary among jurisdictions, but the following are common situations in which the coroner or ME typically becomes involved and a postmortem examination, or forensic autopsy, is performed:

- Violent deaths (accidents, homicides, suicides)

- Deaths that occur in the workplace, usually as a result of traumatic circumstances, poisoning, or exposure to toxins

- Deaths that are suspicious, sudden, or unexpected

- Deaths that occur during incarceration or while the deceased was in police custody

- Deaths that are unattended by a physician, that occur within 24 hours of admission to a hospital, or that occur in any situation where the deceased is admitted while unconscious and never regains consciousness prior to death

- Deaths that occur during medical or surgical procedures

- Deaths that occur during an abortion, regardless of whether the procedure was performed by a medical professional, by the pregnant woman herself, or by some unqualified person

- When a known or unidentified body is discovered unexpectedly (a found body)

- Prior to disposal of a body by means of cremation or burial at sea

- Upon the request of the court

Not all cases that fall into one of these categories require an autopsy. The ME has the final say. Whenever reviewing a case, the ME has several options for handling it.

If the cause of death is obvious and the circumstances aren’t suspicious (a patient with severe heart disease dies at home, for example), the ME may accept a cause of death reported by any of the victim’s physicians before issuing and signing a death certificate.

If the death is unusual or suspicious, the ME may employ the autopsy to help determine the true cause and manner of death. In this situation, the ME may perform a complete or partial autopsy. For example, if a young, healthy person dies from blunt head trauma, the ME may decide a complete autopsy isn’t necessary, and the exam may be confined to only the head. A partial autopsy can save time and money, so the ME often does the minimal work necessary to make the needed determination. It’s completely up to the ME.

Performing an Autopsy

Autopsies are designed to determine how, when, and why someone died. During an autopsy, the ME uses a wide variety of tools and a fair amount of intuition to determine what happened. Everything from the debris found under a victim’s fingernails to the contents of his stomach can lend clues. The investigation proceeds from the big picture to the fine details and from the outside of the body in.

Getting to work on a given case as soon as the ME’s workload permits is vitally important because a corpse deteriorates rapidly; however, a four- or five-day stay in a refrigerated vault usually won’t cause any damage to the body that inhibits an investigation.

Identifying the body

Whenever a death becomes the subject of a criminal proceeding, the identity of the deceased cannot be left in doubt. If the identification is unconfirmed, any evidence gleaned from the body is of little use in court.

Generally, however, the identity of the person is not open to question. Family members or friends usually come forward to confirm this information. If not, photos, fingerprints, and dental records may be used to make a positive identification. See Chapter 10 for more about how investigators unearth the identity of a Jane or John Doe.

Conducting an external examination

Whenever possible, a thorough external examination of the body, which includes a search for evidence of obvious trauma or illness, begins at the crime scene. Practical considerations, such as adequate light and space, limit this practice in many instances. The ME or one of the coroner’s technicians nevertheless should visit the scene before the body has been moved or removed to observe the body’s position and its relationship to other crime-scene evidence, such as the perpetrator’s points of entry and escape, weapons, shoe impressions, fingerprints, blood spatters, or any other crime-scene discoveries.

The ME is careful not to touch the body or move it any more than is absolutely necessary during a crime-scene examination primarily to avoid losing or contaminating any evidence related to the body.

After arriving at the morgue, the body is removed from the transport wrappings and placed on an autopsy table. Crime lab technicians transport the sheets and the body bag to the crime lab, where they search for trace evidence such as hair, fibers, dirt, paint chips, and other materials.

Measuring and weighing

The first step in the actual postmortem examination of any body is to determine the corpse’s height and weight. The ME records this information along with age, sex, race, and hair and eye colors.

Photographing the body

The body also is photographed, both clothed and unclothed, and at various stages during the autopsy. Frontal and profile pictures of the face and body are important, particularly if the victim’s identity hasn’t been thoroughly established. Every scar, birthmark, tattoo, and unusual physical feature is documented. Every injury must be adequately recorded.

Checking out the victim’s clothing

The ME next examines the clothed corpse, searching for

- Trace evidence, such as hair, fibers, gunshot residues, semen, saliva, or blood stains. Any findings are photographed and then collected.

- Damaged clothing that may correspond with injuries on the body. For example, do the defects in the victim’s shirt match the gunshot or stab wounds found on the body?

After this initial exam, the clothing is removed carefully, to avoid losing any trace evidence, and sent to the crime lab for processing.

Establishing the time of death

Next, the ME determines the state of rigor mortis (stiffening of the muscles) and whether and where lividity (settling of the blood) is present (see Chapter 11 for more on determining time of death). Knowing the position the body was in at the time it was discovered and the location of lividity may indicate whether the body was moved after death.

Taking X-rays

Although they’re not obtained in every autopsy, X-rays can supply critical evidence. X-rays of wounds can reveal the extent of injuries and the general shape and size of whatever object created them, which can help identify the murder weapon. For example, X-rays sometimes reveal that the tip of a knife has broken off and remains behind in the wound.

Bullets tend to deform and break up inside the body, leaving behind chips and fragments that further show the bullet’s path through the body. X-rays often help follow the bullet’s travels and help locate the bullet’s final resting place so that it can be retrieved for examination.

Looking for trace evidence

Hair, fibers, and other foreign materials, as well as blood and semen stains, are examined, photographed, and collected. In traumatic deaths, the victim’s fingernails are clipped or scraped because hair, blood, or tissue from the assailant may be found if the victim struggled with the attacker. In sexual assault cases, the victim’s pubic hair is combed to search for hair from the rapist, and vaginal and anal swabs are obtained to check for the presence of semen. The ME also takes hair samples from the victim’s head, eyebrows, eyelashes, and pubic area for comparison with any foreign hair that’s found on or around the body. All the trace evidence collected from the body is sent to the crime lab for further evaluation.

Fingerprints are taken after all trace evidence, particularly fingernail clippings or scrapings, has been obtained, because small bits of evidentiary material can be lost merely by prying open the hand to take the fingerprints.

Examining injuries

Injuries, whether old or recent, are the next items on the ME’s autopsy agenda. Each injury is examined, photographed, and marked on a diagram, indicating its location on the body and its position relative to anatomical landmarks like the top of the head, the heel of one foot, the midline of the body, or the nipple on the same side as the wound.

These details may be important factors in reconstructing the crime scene. The exact location of a wound can often suggest that the assailant was a certain height or was either right- or left-handed, which, in turn can help pin down or exonerate a suspect. For example, the suspect may simply be too short to have stabbed the 6-foot-tall victim in the neck with a downward motion.

Three of the common injuries MEs encounter are

-

Lacerations and contusions: Lacerations (cuts and slices) are photographed and measured. The depth of each is determined, and a search for retained weapon fragments, such as the tip of a knife, is conducted. Bruises, or contusions, from blunt trauma are measured and photographed.

When they are widely scattered over the arms, legs, and torso of the victim, bruises and cuts suggest that a struggle took place or that the victim was tortured before death. Bruises and cuts on the arms and hands may indicate that the victim tried to fend off the attacker. Such injuries are called defensive wounds. Contusions may be seen around the throat in cases of manual or ligature strangulation.

When they are widely scattered over the arms, legs, and torso of the victim, bruises and cuts suggest that a struggle took place or that the victim was tortured before death. Bruises and cuts on the arms and hands may indicate that the victim tried to fend off the attacker. Such injuries are called defensive wounds. Contusions may be seen around the throat in cases of manual or ligature strangulation. -

Stab wounds: In stabbings, the ME carefully determines how many wounds are present and then measures the width, thickness, and depth of each. The ME also tries to determine which wound was the killing thrust and whether the wounds were caused by a single- or double-edged blade or blades. This information can be critical in cases where more than one assailant took part in the crime, because it can have a direct impact on how charges are leveled against the perpetrators. The one who actually did in the victim faces the more serious charges.

In some passionate or overkill homicides, so many wounds may have been inflicted that an accurate count isn’t possible. When that’s the case, the ME determines the minimum number of wounds.

Hesitation wounds often accompany suicide attempts involving a knife. These are small nicks and cuts inflicted by someone who’s gathering the courage to make a fatal cut.

- Gunshot wounds: Entry wounds from gunfire are measured and photographed. The bullet’s angle of entry and the gun’s distance from the body when it was fired are estimated (see Chapter 18). X-rays are helpful for following the bullet’s path through the body and for locating its final resting place. This information is used during the dissection not only to find the bullet but also to assess the extent of any internal organ and tissue damage it may have inflicted.

If the murder weapon is available, the ME compares it with the injuries to determine whether it is the device that actually caused the injuries. X-rays provide considerable help in making this determination. A depressed skull fracture or a series of fractured ribs whose dimensions mirror that of the suspected murder weapon can be important evidence.

Dissecting the body

Dissection is the part of an autopsy that usually makes its way into horror movies and cop shows, because that’s when the body actually is opened up for internal examination. The steps taken by the ME during the autopsy dissection include the following:

-

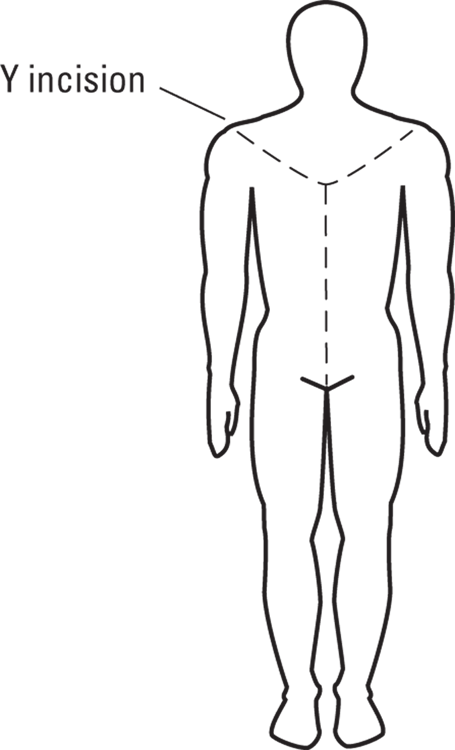

Making the incision.

The ME makes a Y-shaped or similar incision (see Figure 9-1) to the front of the body. This incision has three arms, two extending from each shoulder down to the lower end of the sternum (breastbone) and the third continuing down the midline of the abdomen to the pubis. The ribs and clavicles (collarbones) are then cut with a saw or shears and the breastplate is removed, exposing the heart, lungs, and blood vessels of the chest.

-

Removing the heart and lungs.

The heart and lungs can be removed sequentially but more frequently are removed en bloc, or as one unit. Blood for typing, DNA analysis (when necessary), and toxicological testing is often taken from the heart, the aorta, or a peripheral vein.

-

Examining the abdomen.

After the heart and lungs are removed, the ME focuses on the abdomen. Each organ is weighed and examined, and tissue samples are taken for microscopic examination.

-

Collecting samples.

The contents of the stomach are examined, and samples are taken for toxicological examinations. Stomach contents can help the ME determine the time of death if the content and timing of the victim’s last meal can be determined (see Chapter 11). In addition to stomach contents, ocular (eye) fluid, bile from the gall bladder, urine, and liver tissue samples are taken and submitted for toxicological testing (see the next section “Sniffing out clues in chemicals: Toxicology”).

-

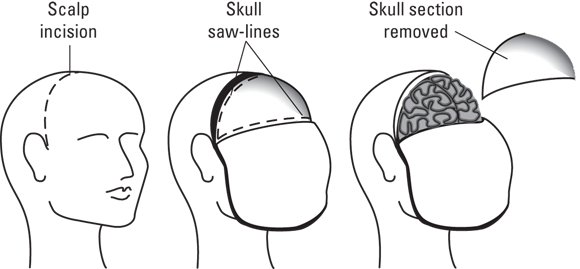

Opening the head and peeking at the brain.

The ME looks for evidence of head trauma and/or skull fractures and then opens the skull to view the brain. First, an incision is made from just behind one ear, over the top of the head, to just behind the other ear (see Figure 9-2), so that the scalp can be peeled forward, exposing the skull. A saw is used to remove a portion of the skull to expose the brain. The ME examines the brain first in situ (in place) and then removes it for a thorough inspection and for taking tissue samples.

-

Returning the organs and suturing the body.

After each organ has been examined and samples have been taken for later microscopic examination, the organs are returned to the body, and the incisions are sutured closed. The body is then released to the family for burial.

Illustration by Nan Owen

FIGURE 9-1: The Y-shaped incision used during most autopsies enables the ME to remove the breastplate to examine and remove the heart and lungs.

Illustration by Nan Owen

FIGURE 9-2: The steps needed to remove the brain during an autopsy.

Sniffing out clues in chemicals: Toxicology

Body fluids and tissues collected during the dissection are sent to the toxicology lab for drug and poison testing. Here’s what they may show:

- Stomach contents and ocular fluid may reveal any drugs the victim ingested during the hours before death.

- Urine and bile may indicate what drugs the victim used during the past several days.

- Hair may show signs of chronic heavy metal (arsenic, mercury, and lead) ingestion as well as other drug use such as GHB.

- Blood is particularly useful for determining levels of alcohol and other drugs.

Filing the Official Autopsy Report

After the ME uncovers everything he can from the autopsy, he summarizes his findings in an autopsy report, which is a legal document that may become part of any court proceeding and can be requested by the prosecution, the defense, or the judge. It also may be released to the public (or not) at the discretion of the ME and the court.

The ME’s final official report consists of all the details uncovered during the examination as well as any conclusions the ME drew about the cause and manner of death.

The ME typically is cautious whenever filing any kind of report regardless of whether it’s preliminary or final. The ME may wait for lab results (toxicology reports, for example) to be returned or file a preliminary statement that will be updated when the rest of the results arrive.

Because the ME’s findings and opinions often make or break a case, every pathologist has a particular method and style of preparing the final report, but certain information must be included.

- Complete description of the body and its external examination

- Description of any visible injuries

- Description of any illnesses or injuries to the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord)

- Detailed descriptions of the internal examination of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis, which include any abnormalities or injuries found in any of the internal organs

- Description of any abnormalities found during microscopic examination of organ tissues removed at autopsy

- Results of all toxicological examinations

- Results of other laboratory tests

- Pathologist’s opinion, which includes assessment of the cause, mechanism, and manner of death

It’s important to note that the official autopsy report and the ME’s final conclusions are not written in stone. If new evidence is uncovered or if a delayed test result arrives that changes the ME’s opinion, the report can be altered or amended to reflect this.

Because signs of life can be difficult to accurately interpret, several methods for determining whether a person died were devised and used long ago, when science was in its infancy. Among them were

Because signs of life can be difficult to accurately interpret, several methods for determining whether a person died were devised and used long ago, when science was in its infancy. Among them were  The invention of the stethoscope enabled physicians to determine the presence or absence of breathing and a heartbeat, thus making death a little easier to pronounce. The development of the electrocardiogram (EKG), a device that records the electrical activity of the heart, followed, and the combination of these two devices gave physicians a much more objective measure of death. The 20th century saw the development of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) followed by the use of ventilators and pacemakers that are capable of keeping the heart and lungs working even after death. And the water suddenly became muddier. These advancements brought about the concept of brain death, which means that although the heart and lungs may be working, the brain is dead.

The invention of the stethoscope enabled physicians to determine the presence or absence of breathing and a heartbeat, thus making death a little easier to pronounce. The development of the electrocardiogram (EKG), a device that records the electrical activity of the heart, followed, and the combination of these two devices gave physicians a much more objective measure of death. The 20th century saw the development of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) followed by the use of ventilators and pacemakers that are capable of keeping the heart and lungs working even after death. And the water suddenly became muddier. These advancements brought about the concept of brain death, which means that although the heart and lungs may be working, the brain is dead. Simply put, the cause of death is the reason the individual died. A heart attack, a gunshot wound, and blunt force head trauma with intracranial bleeding are causes of death. They are the diseases or injuries that altered the victim’s physiology and led to death. The mechanism of death is the actual physiological change, or variation in the body’s inner workings, that causes the cessation of life.

Simply put, the cause of death is the reason the individual died. A heart attack, a gunshot wound, and blunt force head trauma with intracranial bleeding are causes of death. They are the diseases or injuries that altered the victim’s physiology and led to death. The mechanism of death is the actual physiological change, or variation in the body’s inner workings, that causes the cessation of life.