Chapter 18

Bang! Bang!: Analyzing Firearms Evidence

IN THIS CHAPTER

Getting to know guns

Getting to know guns

Analyzing bullets and shell casings

Analyzing bullets and shell casings

Matching rifling patterns

Matching rifling patterns

Handling gunshot residues

Handling gunshot residues

Guns are a source of pleasure and sport for many people and, when used properly, are safe. But watch a movie, any movie, and odds are that someone, and often several someones, will be shot. Guns have been a movie staple for many years. Old westerns always involved a gunfight or two, and if you view any current TV dramas, you’re likely to see that cops, private investigators, criminals, gang members, and just about everyone has a gun. And real life isn’t far behind. Watch the news or read a newspaper any day of the week, and you’re bound to find that a gun was used in some illegal way.

In fact, guns commonly are used in criminal activities. Besides their obvious capacity for murder and injury, guns are an effective means for gaining control. In armed robberies, abductions, and rapes, having a gun can ensure compliance from the victims. Deaths from gunshots can be accidental, suicidal, or homicidal. In a homicide, evidence from the gun or ammunition often proves to be the perpetrator’s undoing.

This area of forensic investigation is often erroneously called ballistics. In fact, ballistics is the study of how projectiles — bullets, rockets, mortar shells — travel through space. Gun and bullet examination is actually firearms examination, which is performed by specially trained forensic firearms examiners. They commonly have to

- Analyze bullets and shell casings found at a crime scene to determine what type of weapon fired them

- Help with crime-scene reconstruction by estimating the distance between the gun muzzle and the victim or working out the trajectory of the bullets

- Match a bullet or shell casing to a particular weapon or to a sample from a different crime scene to link the two

Figuring Out Firearms

Have you ever fired a gun? Most people vividly remember their first time. The sudden explosive discharge is shocking. Even if you expected the recoil, it probably was more of a jolt than you anticipated.

Guns typically are classified as handguns, rifles, or shotguns:

- Handguns, as the name suggests, are held and fired in one hand (as opposed to rifles and shotguns, which you brace against your shoulder to fire) and fall into one of the following three categories:

- Revolvers are the handguns that you see in old westerns. Bullet and shot cartridges (shell casings loaded with a primer, gunpowder, and bullets or shotgun pellets) are placed into a cylinder that revolves with each pull of the trigger, bringing the next cartridge in front of the gun’s firing hammer in a sequential manner. After a bullet is fired, its shell casing remains in the cylinder until it’s manually removed.

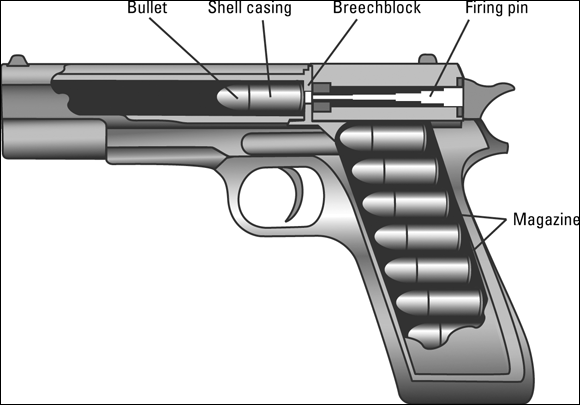

- Semiautomatic pistols (see Figure 18-1) are loaded using a magazine or clip. The clip is basically a spring-loaded device that holds a stack of cartridges that typically slides into the handle of the pistol. This type of weapon, like the revolver, fires once for each pull of the trigger. Some of the explosive energy is used, however, to automatically eject the empty shell casing from the gun, and the spring in the clip seats the next cartridge into the firing chamber.

- Machine pistols are truly automatic weapons. They possess a clip similar to that of a semiautomatic pistol and, when fired, use some of the explosive power from each spent round (cartridge) to expel an empty casing and bring the next cartridge into the firing chamber. The major difference between these pistols and semiautomatics is that machine pistols fire repeatedly as long as the trigger is depressed and ammunition is available in the clip.

- Rifles often utilize a lever or a sliding bolt to eject a spent cartridge and bring the next one into the firing chamber. Rifles also can be semiautomatic or automatic.

- Shotguns, in general, don’t fire bullets but rather shells filled with groups of pellets (shot). As the shot exit the barrel, they spread out in a circular pattern, which means shotguns don’t require as much aiming. You just have to point them in the intended direction.

Illustration by Nan Owen

FIGURE 18-1: Anatomy of a handgun.

Extracting Info from Ammo

Rarely do investigators find a smoking gun at a crime scene — in large part because most powders used these days are smokeless — but even a metaphorically smoking gun is hard to come by. Bullets, however, are the next best thing and can go a long way toward helping a forensic firearms examiner determine what kind of gun was used, and by whom.

Unfortunately, an examiner often doesn’t have an intact bullet for analysis. More often, the examiner gets a severely damaged bullet or a bullet fragment; however, even a bullet or fragment that is not severely deformed or too small to use, still can provide a wealth of information.

Handling bullets

During the collection and handling of any crime-scene bullets, the investigator must take great care not to damage or alter them. Whether removed from a body in surgery or during an autopsy or from a wall at the crime scene, bullets need to be handled carefully. For example, a bullet can be damaged when grasped with a surgical instrument or pried from a doorjamb, altering the striation pattern and making a match of the bullet with a suspect weapon impossible.

Bullets also may have important trace evidence attached. Paint, fibers, and other materials may cling to the bullet as it passes through or ricochets off walls, doors, bricks, or window screens. Sometimes, a fired bullet yields DNA, if investigators find small bits of flesh and blood attached to it.

Breaking down bullets

A forensic firearms examiner assesses the chemical and physical composition of a bullet to determine its manufacturer and shorten the list of suspected weapons. You can find most bullet types in weapons of varying calibers and muzzle velocities, but softer bullets are more common in low-velocity weapons, and harder or jacketed bullets usually are used in high-velocity weapons.

Bullets are categorized as follows:

- Lead bullets are soft and usually used in low-velocity weapons, like small-caliber handguns and rifles with .22 and .25 calibers. These bullets deform and fragment significantly when they strike a target. Although they penetrate less, the deformation and fragmentation of the bullet can cause severe tissue damage (see Chapter 12).

- Lead alloy bullets contain lead and small amounts of one or more other metals that make them harder. Antimony and tin commonly are alloyed with lead to make bullets for high-velocity weapons. Because of their increased hardness, these bullets tend to deform and fragment less and penetrate deeper.

- Semijacketed bullets have a thin layer of brass coating their sides. The soft lead nose is exposed, enabling the bullet to expand and fragment upon impact. The exposed nose may be slightly hollow, making it a hollow-point bullet, a type that deforms and fragments even more and causes a great deal more tissue damage in the person that it strikes. These bullets are used in low-velocity weapons as well as higher-velocity ones, such as .357 and .44 magnum handguns and high-powered rifles.

- Fully jacketed bullets are completely covered, even the nose. Brass-covered ones are often called full metal jackets. They typically are used in high-velocity guns, such as .44 magnum handguns and high-powered rifles. They have greater penetrating power than other bullets. Besides brass, bullets can be jacketed with Teflon, nylon, and other synthetics. These materials are tough and slippery, serving as lubricants that result in very high muzzle velocities and a high degree of penetrability. Many of these types of bullets can penetrate body armor and thus are known as cop killers.

Determining caliber and gauge

The caliber and type of bullet are important in determining what weapon was used in a crime. If the bullet is intact, or mostly so, the police can determine the caliber by simple measurement. Severely deformed bullets can be weighed, but weighing them doesn’t give the exact caliber; it serves only to eliminate some calibers. For example, the weights of .22 caliber and .44 caliber bullets vary considerably. Investigators can often easily determine whether the bullet is jacketed and, if so, with what, thus helping to identify the type of bullet and ultimately the type of weapon.

Shotgun pellets can be extracted from the victim during surgery or an autopsy, and from walls, furniture, and other surfaces. The size of the shot doesn’t reveal the gauge of the shotgun but does provide information about the ammunition used. The various sizes of shot are numbered; the lower the number, the larger the pellets within the shotgun shell. For example, Number 8 shot is smaller than Number 4. Pellets vary in size from 0.05 inches for Number 12 shot to 0.33 inches for 00 shot, the largest, which also is called double-O buckshot. An examiner measures the diameter of any recovered shot and estimates what size shot was used.

Shuffling through shell casings

A shell casing is the portion of the cartridge that remains after the powder explodes and the bullet is gone. Shell casings often are the only evidence a firearms examiner has to work with. Fortunately, they retain many marks that are of interest to the examiner, including:

- The impression left by the firing pin: A simple inspection of the base of the casing shows where the firing pin struck, revealing whether the shell had a primer cup (center-fire) or had primer around its edge (rim-fire). Knowing where the firing pin struck narrows down the list of possible gun types.

- Breechblock patterns: The breechblock is the back wall of the firing chamber (see Figure 18-1). When powder in the casing detonates and pushes the bullet down the barrel, the casing is forced back against the breechblock, leaving an impression on the bottom of the casing.

- Headstamps: Cartridge manufacturers stamp this information into the metal of cartridge casings and shotgun shells when they’re made. These impressions sometimes are the manufacturer’s initials or logo, the caliber or gauge, or the cartridge type.

- Extractor and ejector marks: Automatic and semiautomatic weapons have mechanisms that pull the next bullet from the clip and seat it in the firing chamber (extractor) and that remove the spent shell from the chamber, pushing it from the weapon (ejector). Extractors and ejectors vary among weapons, leaving their own unique scratches and marks on the sides of the shell casings.

Getting Groovy: Comparing Rifling Patterns

Bullets don’t pass through gun barrels unscathed but are nicked and scratched along the way. These markings help forensic firearms examiners match bullet to gun type, and maybe even to one particular gun.

Understanding rifling

A spinning bullet is a more accurate bullet, so most guns are rifled, meaning spiral grooves are etched or cut into the inside of their barrels to make bullets spin as they’re expelled. Cutting the grooves leaves lands, or high parts, intact between them. The grooves grab the bullet as it travels down the barrel, causing it to spin and thereby greatly increasing its accuracy. Old smoothbore rifles weren’t accurate beyond 100 feet or so, but modern rifled firearms are extremely accurate, some even for thousands of yards.

But the accuracy of spinning bullets isn’t what interests forensic firearms examiners. They’re more interested in how the lands and grooves of the rifling mark the bullet. As I discuss in the next section, these markings provide class and individual characteristics (see Chapter 3).

When a gun barrel is manufactured, the rifling is cut, stamped, molded, or etched inside of it. The depth of the grooves, the width of the lands, and the direction and degree of the twist vary among different types of weapons and different manufacturers. These characteristics help examiners identify the type of weapon that fired a crime-scene bullet and its manufacturer.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) maintains a database known as the “General Rifling Characteristics File” to help firearms examiners make these determinations. It lists the land, groove, and twist characteristics of known weapons. Bullet and shell casings likewise can be compared with bullets and casings recovered from other crime scenes that are listed in other databases (see the later section “Searching for answers in databases”).

Because smoothbore weapons like shotguns and older firearms aren’t rifled, their projectiles don’t exhibit any evidence of markings caused by lands, grooves, or twists.

Reading the ridges

When lands and grooves grab and spin a bullet traveling down the barrel of a gun, they also cut into the bullet, leaving behind characteristic markings that are at the heart of firearm comparisons. These markings, called striations, are linear and parallel to the long axis of the bullet. They’re more prominent on soft lead bullets than they are on metal- or Teflon-jacketed ones. (Check out the earlier section “Breaking down bullets.”)

Silencers are devices that muffle the sound of a gun and can range from a towel wrapped around the barrel to a sophisticated sound-absorbing attachment. These attachments may also leave markings on bullets, but these markings are unpredictable. If the silencer does leave behind markings on the bullet but isn’t available at the time the crime lab test-fires the gun, these marks can complicate the examiner’s attempts to match the bullet to the gun from which it was fired.

As if all these lands, grooves, twists, and striations weren’t enough, each rifled barrel has minute characteristics that differentiate it from all others. A rifling tool cuts through each metal gun barrel a little differently; furthermore, cutting or etching equipment becomes worn and damaged with each use. This progressive wear and tear produces rifling patterns that vary from barrel to barrel. In addition, repeated firing wears down and damages the grooves and lands, adding even more individual characteristics to the barrel and thus to any bullet that travels through it.

Comparing individualizing striations is useful in many situations. The first step in making such a comparison is obtaining an intact bullet fired from the suspect weapon. Most firearm labs have a test-firing chamber. An examiner then views the lab-fired bullet next to the crime-scene bullet, using a comparison microscope (see Chapter 7), which places images of the two bullets side by side to facilitate accurate comparisons.

For example, bullets found at a crime scene can be compared to find out whether they came from only one gun. If not, more than one weapon obviously was used. Likewise, separate bullets, each collected from different crime scenes, can be compared to determine whether the same gun fired them. Such a match strongly connects the two crimes. Most importantly, a bullet removed from a homicide victim can be compared with a bullet that’s been test-fired from a suspect weapon. A match means that you have identified the murder weapon, which, in turn, may be the key to identifying the killer.

Searching for answers in databases

Even with only a single bullet or shell casing and no suspect bullet or weapon to compare them with, the firearms examiner often can determine the type and manufacturer of the weapon that fired the bullet. And thanks to computer technology and firearms databases, it is often possible to compare ballistic markings on the crime-scene bullet with the markings on bullets from weapons used in other crimes. The major database is the Integrated Bullet Identification System (IBIS). Maintained by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives’ (BATFE) National Integrated Ballistics Information Network (NIBIN), IBIS is by no means complete, but if a bullet or casing from the same weapon is in the system, a match to the crime-scene bullet or casing can connect two or more cases and thus aid in solving them all. This system rapidly compares hundreds of records and indicates any possible matches. An experienced firearms expert then visually conducts the final match.

The Proof’s in the Powder: Gunshot Residues

Without a gun, a bullet, or even a shell casing to work with, firearms examiners may be able to draw some conclusions using chemical residues from expended gunpowder. Traces of these residues can linger at the scene and on the victim and shooter. Although it doesn’t tell the entire story, finding this kind of chemical evidence on a suspect connects that person to the scene and gives investigators a good reason to dig deeper.

As can be seen with bite marks (Chapter 12) and some types of trace evidence (Chapter 17), the chemical analysis of gunshot residue, as well as the chemical analysis of bullets to help determine manufacturer, has drawn fire — no pun intended. Again, the lack of standardization of testing procedures and examiner training has led the FBI and other labs to reconsider this type of evidence.

Tracing gasses and particles

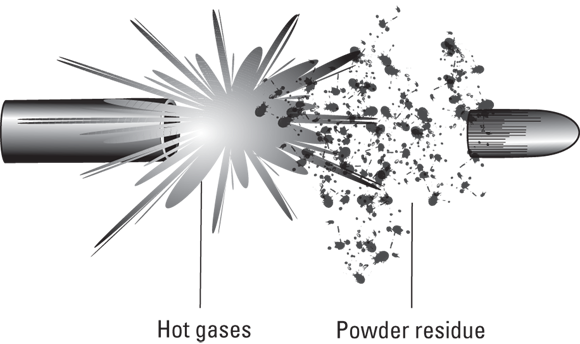

When a gun is fired, the primer and the powder explode within the cartridge, forcing the bullet down the barrel. Much but not all of the explosive gases and particulate matter produced by the explosion follows the bullet (see Figure 18-2). However, some of these materials escape through openings in the weapon. This factor is particularly true of revolvers, which tend to leak more gases than other types of weapons.

Illustration by Nan Owen

FIGURE 18-2: Residue from exploding primer and powder when a gun is shot.

Wind and rain can change the pattern of or lessen the spread of the GSR cloud. As a result, an examiner may find GSR in unexpected areas. On light-colored clothing, GSR patterns are readily visible as smudges or smears, but on dark, multicolored, or bloodstained clothing, the patterns can be obscured.

Testing for GSR

The goal of GSR analysis is placing a suspect near the gun when it was discharged. Unfortunately, simply being near the gun when it discharges or handling the gun afterward can leave behind GSR on an innocent person. GSR also tends to fade rapidly and usually dissipates after a few hours. It can be wiped or washed away, which is why testing needs to be accomplished as soon as possible after the gun is fired.

Investigators inspect any suspect’s hands, face, and clothing and obtain samples. The old paraffin test, where melted paraffin is used to pick up residues from the shooter’s hands, rarely is used anymore. Instead, investigators swab the suspect’s hands, arms, and clothing with a moist swab or filter paper to obtain samples.

Determining distance

In Chapter 12, I tell you how the distance between the muzzle of the gun and the victim affects the anatomy of entry wounds. When a gun is fired, hot gases and burned and unburned gunpowder particles follow the bullet out of the barrel. The ME usually can estimate the firing distance by the effects of these substances on the wound.

Sometimes, however, the victim is shot through clothing, such as a shirt or jacket, and the tattooing and charring that the gases and unburned powder normally cause on the victim’s skin are intercepted by the clothing. The ME therefore is left with few, if any, distance markers on the victim’s skin. Enter the firearms examiner.

The examiner uses the suspect weapon and similar ammunition to perform a series of test firings into similar fabric and accurately estimate the distance. Test firings are made at 6 inches, 1 foot, 18 inches, 2 feet, and 3 feet, and the examiner then compares the residue patterns on the test garments with those found on the victim’s clothing to find the closest match.

Guns work by instigating an explosion that sends a bullet racing out of the barrel. When you pull the trigger of a gun, its firing pin strikes a cylinder of primer in the shell of the bullet and ignites it, causing gunpowder in the shell to explode. The explosion pushes the bullet through and out of the gun’s barrel with tremendous velocity.

Guns work by instigating an explosion that sends a bullet racing out of the barrel. When you pull the trigger of a gun, its firing pin strikes a cylinder of primer in the shell of the bullet and ignites it, causing gunpowder in the shell to explode. The explosion pushes the bullet through and out of the gun’s barrel with tremendous velocity. The caliber of a weapon is a measurement of the internal diameter of its barrel. The caliber of rifles and handguns is measured in inches or millimeters (mm). A .38 caliber handgun has a barrel with an internal diameter of 0.38 inches; a 9 mm has a 9 mm barrel diameter. Shotgun gauges also are measurements of the barrel’s diameter; however, they don’t reflect a direct measurement. Instead, the gauge of a shotgun is determined by counting the number of lead balls matching the barrel’s diameter that it takes to weigh one pound. Twenty lead balls the diameter of a 20-gauge shotgun barrel weigh one pound. One exception is the .410 shotgun, the barrel of which is .410 inches in diameter.

The caliber of a weapon is a measurement of the internal diameter of its barrel. The caliber of rifles and handguns is measured in inches or millimeters (mm). A .38 caliber handgun has a barrel with an internal diameter of 0.38 inches; a 9 mm has a 9 mm barrel diameter. Shotgun gauges also are measurements of the barrel’s diameter; however, they don’t reflect a direct measurement. Instead, the gauge of a shotgun is determined by counting the number of lead balls matching the barrel’s diameter that it takes to weigh one pound. Twenty lead balls the diameter of a 20-gauge shotgun barrel weigh one pound. One exception is the .410 shotgun, the barrel of which is .410 inches in diameter. Infrared photography can reveal GSR residues under less-than-ideal circumstances. The Griess test may also reveal the pattern. In this test a sheet of photographic paper or a sheet of acetic acid–dampened filter paper is pressed over the area and then immersed in a reagent that reacts with inorganic nitrites in the GSR, revealing the pattern.

Infrared photography can reveal GSR residues under less-than-ideal circumstances. The Griess test may also reveal the pattern. In this test a sheet of photographic paper or a sheet of acetic acid–dampened filter paper is pressed over the area and then immersed in a reagent that reacts with inorganic nitrites in the GSR, revealing the pattern.