46 Adolf Loos: living room, Moller House, near Vienna, 1928. Four steps separate the two levels.

Inspired by a new machine aesthetic, the modern movement stripped away unnecessary ornament from the interior. Mass production was now established as the means of manufacturing consumer goods, and modern movement theorists were inspired by the concepts of rationalization and standardization. New materials and building techniques were to be used to create a lighter, more spacious and functional environment. The early modern designers hoped to change society for the better with the creation of a healthier and more democratic type of design for all.

The first designer categorically to reject the need for ornament in interior design was the Austrian architect Adolf Loos (1870–1933). Loos’s three years spent in America from 1893 to 1896 may explain his total aversion to the florid excesses of art nouveau and the ‘precious’ interiors of the Wiener Werkstätte. During his time in America he became familiar with the work of Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright, and he missed the formative years of art nouveau in Europe. This, together with an admiration for the British arts and crafts movement, led Loos to reject ornamentation as degenerate. His best-known critical essay, ‘Ornament and Crime’, first published in the liberal Neue Freie Presse in January 1908, argued that the urge to decorate surfaces was primitive, and instanced a link between tattoos and modern criminals and the case of graffiti on lavatory walls as evidence. While such polemic was obviously not to be taken too seriously, Loos did succeed in challenging the belief of the art nouveau designers that all surfaces should be decorated. His writing and interior design inspired the generation of architects that went on to create the modern movement.

46 Adolf Loos: living room, Moller House, near Vienna, 1928. Four steps separate the two levels.

47 Adolf Loos: American Bar, Kärntnerstrasse, Vienna, 1907. Mirrors provide recession and the play of rectangles.

Loos worked as an interior designer in pre-war Vienna on a variety of domestic and public commissions. His designs for the Leopold Langer Flat of 1901, his own flat of c. 1903 and the Steiner House of 1910 reveal his skill in handling interior spaces. Exposed beams and modest furniture create a comfortable rather than ostentatious interior. Loos used built-in furniture whenever possible as part of his Raumplan, or plan of volumes. This involved the complex ordering of internal space, culminating in the split-level areas of the Moller House of 1928 in Vienna and the Müller House of 1930 near Prague.[46] The horizontal and vertical elements of the living room of the Moller House are emphasized by black ceiling beams and black wooden strips outlining the door frame, shelving and window frame, to give an overall effect of the play of rectangular planes. Loos’s expert handling of space is also demonstrated in public commissions such as the American Bar in the Kärntnerstrasse, Vienna, of 1907.[47] Here the coffered yellow marble ceiling and plain green marble piers are reflected in mirrors that are set above the high mahogany wainscotting to give the impression of greater space in a room measuring only 3.5 by 7 metres (11½ by 23 feet). Because of the height of the mirrors the customer is not reflected, and the illusion of depth is enhanced.

Although feted by the modern movement (‘Ornament and Crime’ was reprinted in Le Corbusier’s L’Esprit Nouveau in 1920), Loos never joined its ranks. He acted as a catalyst for the sweeping away of surface decoration, but his work was rooted in the nineteenth century and not concerned with the problems of mass production. Peter Behrens (1868–1940) was another architect of Loos’s generation to inspire the modern movement. Behrens’s work for AEG, the German general electrical company, forged new links between art and industry. Behrens gave the company’s graphics, industrial design and factories a clean-lined, modern look and made full use of newly developed materials. The AEG Turbine Factory of 1909–10 in Berlin was constructed of poured concrete and exposed steel. No attempt was made by Behrens to disguise the structure with applied ornament.

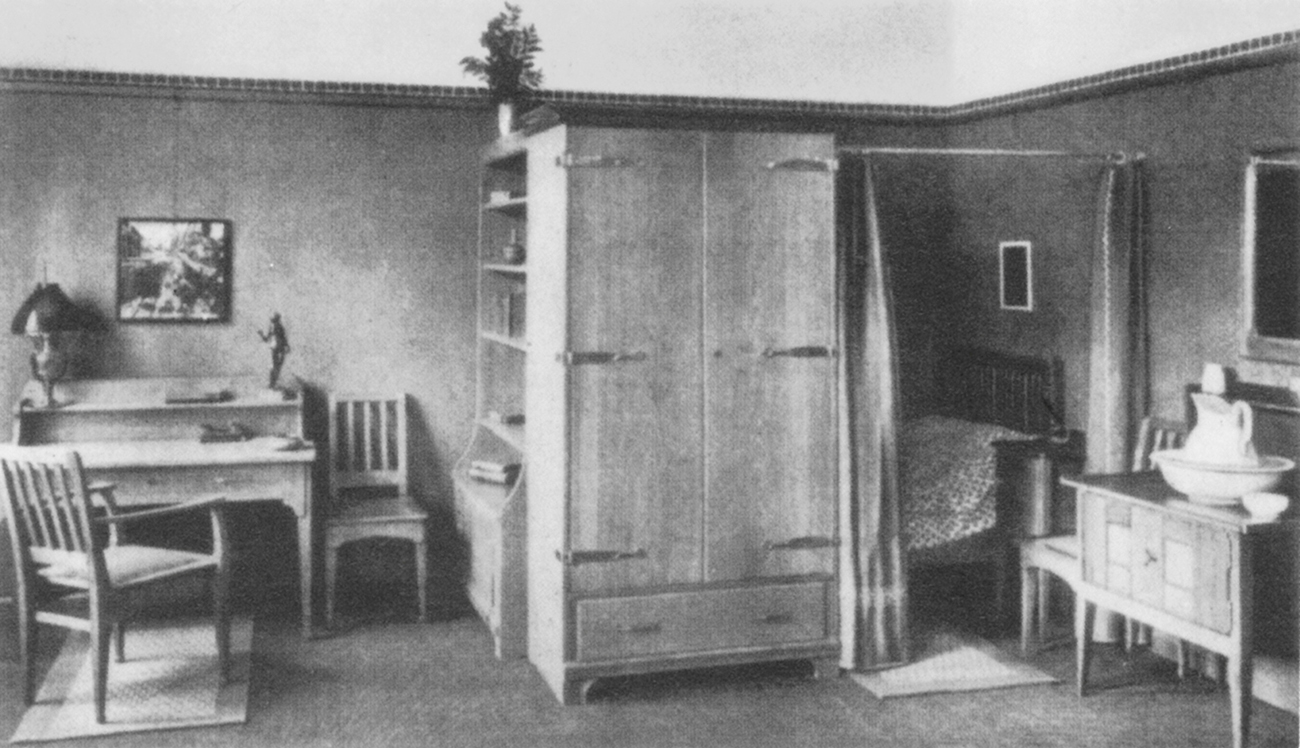

Behrens’s work for AEG was admired by fellow members of the Deutscher Werkbund, a crucial organization for the coming to terms with the age of mechanization. Founded in 1907 in Munich with the support of Hermann Muthesius and Henry Van de Velde, it aimed to improve German design by bringing manufacturers and artists together. By 1910 it had more than seven hundred members, of whom roughly half were industrialists and half artists. Rather than ignoring mass production, the Werkbund attempted to raise design standards for industry with a campaign featuring approved products in yearbooks and public propaganda. Designers involved with the Werkbund attempted to apply the new aesthetic of functionalism to the interior. Karl Schmidt was a founder member of the Werkbund and director of a furniture manufacturers, the Deutsche Werkstätten. With the help of the Werkbund designer Richard Riemerschmid (1868–1957) the firm set up a new factory for the mass production of standard furniture and prefabricated houses. The improvement of mass housing was to be one of the Werkbund’s concerns.[48]

While the Werkbund paved the way for a new aesthetic for mass-produced design, from the first there was a conflict of view between the business and artistic sections. This came to a head at the Werkbund Conference of 1914 when Muthesius proposed that design should be standardized and consist of a limited number of ‘type-forms’, a rationalization which would also benefit the German economy. Van de Velde argued against the reform, protesting that individual artistic inspiration would be crushed. Van de Velde won the majority support of the Werkbund, indicating the strength of fine art values among its members.

Walter Gropius (1883–1969) led the debate on the side of Van de Velde. He was convinced of the importance of individual creativity and artistic integrity while supporting a modernist aesthetic. His compartment for a Mitropa sleeping-car of c. 1914 shows a functional use of limited space, and his design for a shoe-last factory at Alfeld-an-der-Leine for Fagus of 1910–11 (with Adolf Meyer) was a prototype for the modern movement. The influence of Behrens, in whose offices Gropius had worked in 1907–10, can be seen in the monumental simplicity of the building. Its most striking feature is the staircase that runs up one corner, almost completely exposed by huge windows. Gropius made a virtue of new construction techniques. His design for a model factory at the Werkbund’s Cologne Exhibition of 1914 boldly displays the spiral staircase in a wraparound glass tower.

Gropius’s adventurous designs were noticed by Van de Velde, who proposed him as new director of the Weimar Kunstgewerbeschule, later to become the Bauhaus in Weimar. Gropius was appointed director after the war, and the new Bauhaus was established in 1919. The school aimed to teach the arts and crafts in tandem and to bridge the ever-widening gulf between art and industry. The Bauhaus was never to achieve its second aim; it functioned chiefly as a centre for fine art experiment and crafts production, rather than for design for industry. It was important as an international meeting-place for the development of the modern movement style.

48 Richard Riemerschmid: bed-sitting-room, 1907. An economical design for the Deutsche Werkstätten, Hellerau.

At first the emphasis of the school was expressionist. The first Manifesto of 1919 had an expressionist woodcut by Lyonel Feininger on its cover. Expressionist painting had flourished in Germany before the war and then inspired design with an emphasis on exaggerated forms and the fantastic. It had been seen at the 1914 Werkbund Exhibition with Bruno Taut’s Glass Pavilion, inspired by the mystical writer Paul Scheerbart and constructed almost entirely of glass bricks. Erich Mendelsohn’s Einstein Tower at Potsdam (1919–20) and Hans Poelzig’s interior of the Grosse Schauspielhaus, Berlin (1919), are further examples of this fantasy style.[49] Poelzig used huge stalactite forms in the auditorium, built for an audience of five thousand, to create a strange and mystical atmosphere. The movement was short-lived, and was superseded by modernism as designers like Poelzig began to design in a more functional way.

The school’s first commission was for the Sommerfeld House in Berlin in 1921. Designed by Gropius and Meyer with the collaboration of the students, this was built of timber and was a homage to the craft aesthetic of hand-working skills. The school lost its mystical and crafts emphasis during the 1920s with the arrival of new staff who imparted the experimentation of the international avant-garde.

No less important was the impact of De Stijl, a group founded during 1917 in neutral Holland around a small-circulation magazine of the same name. Inspired by the Neoplatonic philosophy of the Theosophists, the painter Piet Mondrian, painter, designer and theorist Theo van Doesburg and designer Gerrit Rietveld created a new aesthetic. Using only primary colours with black, grey and white, the movement attempted to create the ultimate design object which would reflect the universality and perfection of simple geometric forms. With the same purpose the De Stijl designers restricted themselves to horizontal and vertical planes wherever possible. Rietveld’s Red/Blue chair of 1918 was one of the first expressions of this new aesthetic. Constructed from sheets of painted plywood simply screwed together, this seemed to represent the ultimate rethinking of a basic object. Rietveld was able to apply the aesthetic theories of De Stijl to a full-scale project in 1924 when he was commissioned to design the Schröder House in Utrecht with the owner Mrs Truus Schröder.[50] The small suburban house is the supreme example of the De Stijl aesthetic applied to an interior.

49 Hans Poelzig: Grosse Schauspielhaus, Berlin, 1919. Expressionist fantasy at its zenith.

The emphasis on horizontals and verticals and the restricted colour scheme give a visual unity to the exterior and interior of the house. Rietveld was inspired by Japanese house design, and by the work of Frank Lloyd Wright, whose Wasmuth publications of 1910 and 1911 containing his lecture ‘The Art and Craft of the Machine’, as well as plans and photographs of his work, were available to Rietveld in Holland. Both Wright’s living room for the Francis Little House and Rietveld’s interior repeat the motif of horizontal and vertical bars. Rietveld designed the whole building and all the fittings and fixtures throughout. The upper floor was designed to be flexible, with the rooms arranged around a stairwell, and sliding partitions to close off working/sleeping rooms, or, if left open, to allow free circulation throughout the whole floor. This exciting use of space was described in 1924 in Van Doesburg’s ‘Sixteen Points of a Plastic Architecture’, where he writes of De Stijl theory: ‘The new architecture is anti-cubic, that is to say, it does not try to freeze the different functional spacecells in one closed cube. Rather it throws the functional space cells (as well as overhanging planes, balcony, volumes etc.) centrifugally from the core.’

50 Gerrit Rietveld: living room, Schröder House, Utrecht, 1924. Fluid internal space encircling a central stairwell and generous fenestration reduce boundaries to a minimum. The construction of the Red/Blue Chair, 1918, is clearly expressed by the unusual joints, with the various members extending beyond their points of contact. Note the divisions on the floor, which show where sliding partitions can be used to separate living and sleeping areas.

De Stijl theories of design reached the Bauhaus when Van Doesburg (1883–1931) came to Weimar in 1921–3 and set up an unofficial course for Bauhaus students in competition with the still mystical and crafts-oriented official curriculum.

A second avant-garde movement that was to affect the direction of the Bauhaus was Constructivism. After the October Revolution of 1917 Russian avant-garde artists set out to meet the needs of the proletariat with a more material-based art and design. Vladimir Tatlin, Alexander Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova and El Lissitsky were among those who had been fine artists before 1917, but now regarded this role as self-indulgent and superficial. They therefore set out to work at the service of the Revolution, involved with the art schools and later designing practical items such as workers’ clothing. A Soviet art exhibition was organized by El Lissitzky in Berlin in 1922, and his Vesch (‘Object’) magazine brought the message of Russian constructivism to Germany.

51 Félix Del Marle: furniture, Dresden, 1926. De Stijl design by a French exponent, described by the De Stijl painter Piet Mondrian as ‘the best application of neo-plasticism’.

Radical influences such as these began to make an impact on the Bauhaus in the early 1920s. Gropius made changes in the teaching staff, taking on Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944), the Russian pioneer of abstract painting, to run the murals workshop and László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946), the Hungarian Constructivist, experimental painter and photographer, to run the Basic Course. The change of emphasis from crafts to modern design was seen publicly at the first full-scale exhibition of Bauhaus work in 1923. Staged to coincide with the annual Deutscher Werkbund conference held that year at Weimar, the exhibition was a huge success. The school’s new approach was nowhere more visible than in a specially designed house, named for the street in which it was built, the ‘Haus am Horn’.[52] Designed by George Muche with technical advice from Adolf Meyer (1881–1929), it was constructed of steel and concrete. The plan of the house was based on a simple square, with the main living area in the centre, lit by windows in a small upper storey. The emphasis was on function, with each space having a clearly defined purpose to ensure maximum efficiency. The Bauhaus designed and made all the simple, functional fittings and furniture. The kitchen by a student, Marcel Breuer (1902–1981), is an early example of rational domestic design.[53] It has fitted cupboards, a continuous work surface, and uniform storage jars that were already in production.

The exhibition established the Bauhaus’s reputation as a leading force in the creation of a new functional aesthetic. This leadership was consolidated in 1925 when the school was forced to move from Weimar to the industrial town of Dessau, and Gropius was responsible for the design of new accommodation for the school, as well as living quarters for the students and staff. The main site consisted of connected ferro-concrete rectangular blocks for the teaching, administration and student accommodation areas. This was the first example of a large-scale public building in the modern movement style. Gropius used flat roofs throughout, and a huge glass curtain-wall for the four-storey workshop block to supply high levels of light for the studios. Technical virtuosity is celebrated in the pulley system used to open ten windows simultaneously. The Bauhaus workshops were entirely responsible for the design of the interior.[54] The angular metal theatre lighting was designed by Moholy-Nagy and tubular metal seating by Marcel Breuer, the former student, now Bauhaus lecturer.

52 View into the Bauhaus ‘Haus am Horn’, an experimental house built in a street near the school for the 1923 exhibition.

53 Marcel Breuer: kitchen, 1923. One of the earliest examples of a fitted kitchen with matching storage jars, designed for the first full-scale exhibition held by the Bauhaus.

Teaching-staff accommodation was located near the main site. Gropius designed a detached house for himself as Director and three pairs of semi-detached residences for other staff. Like the ‘Haus am Horn’, these quarters were designed strictly with function in mind. Apparently uncomfortable to live in, they were sparsely furnished and decorated with very little colour. This economic approach was best suited to bathrooms and kitchens: the kitchen in Gropius’s own house is a model of efficiency and was equipped with all the latest gadgets, such as a washing machine and eye-level oven.[55]

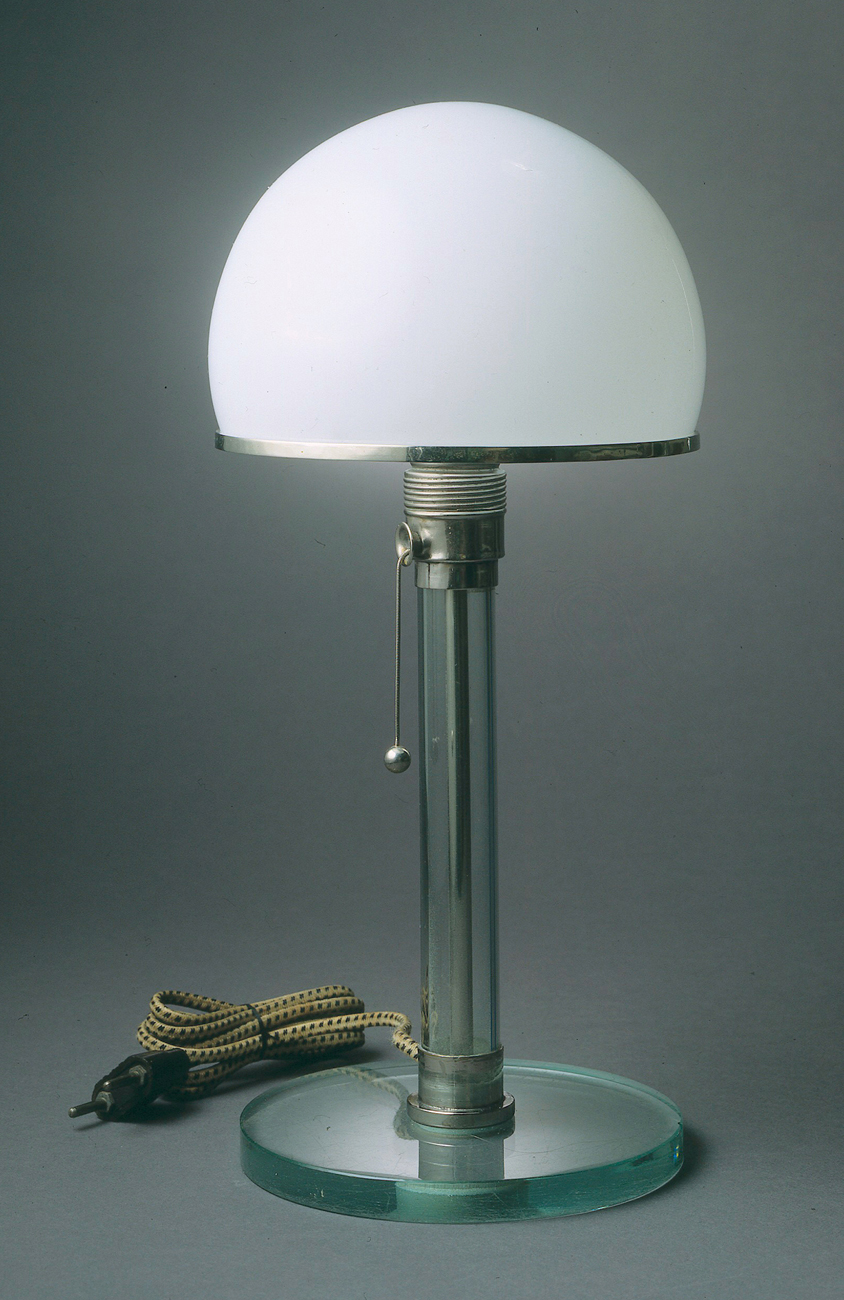

The move to Dessau signalled a mature phase of experimental design at the Bauhaus. Most successful of the prototypes now produced by the Bauhaus workshops were the lamp designs by students such as Marianne Brandt, K.J. Jucker and Wilhelm Wagenfeld, which were manufactured throughout the late 1920s and 1930s. The lamps were marketed as being robust, functional and stylishly modern. More commercially successful but less avant-garde were the patterned and textured wallpaper designs for the firm of Rasch of Bramsche, who began production in 1930. The best-known Bauhaus products are the chairs, now regarded as icons of the modern movement. Breuer’s tubular-steel chairs, notably the ‘Wassily’ chair designed for Kandinsky’s staff house in 1925, were adapted for manufacture by Standard-Möbel.[57] However, the materials and process used were costly, and so this range was far more expensive than the simple bentwood furniture being mass produced by the Austrian firm of Thonet Brothers. Bauhaus design was machine-inspired, and its products were designed to look as if they had been manufactured by a factory for the mass market, whereas in reality their style and cost were more likely to destine them for the fashionable middle-class interior.

In 1928 Walter Gropius resigned as Director and was replaced by the radical architect Hannes Meyer (1889–1954), who believed that the Bauhaus had become too insular and needed to make more contact with the outside world. It was during Meyer’s régime that profitable links with industry were made, most notably with Rasch. He replaced the metalwork and cabinet-making workshops with a new interior design department, responsible for furniture and utensils, and the architectural department became supreme. Twelve Bauhaus students were involved in the design of mass housing at Törten, a suburb of Dessau. Meyer’s Communist sympathies made him unpopular with the Dessau officials and public, and in 1930 he was forced to resign. He was replaced by the far more conservative German architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886–1969).

54 Bauhaus Theatre, Dessau, 1926. Metal and canvas seating by Marcel Breuer and angled metal light fittings by Moholy-Nagy.

55 Walter Gropius: kitchen for the Director’s house, designed after the Bauhaus had moved to Dessau, 1926. Note the latest gadgets such as an eye-level oven.

56 The Director’s office, Bauhaus, Dessau, 1926. The ceiling light is by Moholy-Nagy, inspired by De Stijl. The armchair is by Gropius. The wall-hanging and the rug are by the Bauhaus Weaving workshop. Though ‘decoration’ was alien to the modern movement conception of functional interior design, the teaching of colour theory by the painters Klee and Kandinsky and the activities of the Weaving workshop ensured that colour and pattern retained a role.

Mies was an unpopular choice among the students, whose interests, cultivated by Meyer, lay in the direction of mass housing and the radical possibilities of modern design. German designers elsewhere had been experimenting with such concepts. The ‘Frankfurt kitchen’ which had been designed by Grete Schütte-Lihotzky for the Frankfurt city architect Ernst May in 1926 was one such example.[59] Because of a housing crisis in the city May and his team had had to design functional, cheap dwellings to accommodate the maximum number of people. Since the dwellings were small, special standardized furniture was designed to make the optimum use of space with built-in units. Designers were influenced by space-saving galleys on ships and trains, and by books on efficient household management such as Christine Frederick’s The New Housekeeping, published in New York in 1913 and in Berlin in 1922. Frederick advised on how to save time and effort in the servantless home. She ruled that the kitchen should only be used for the preparation of food, not laundry or eating, and should be as small as possible to reduce the time spent moving between appliances and work areas.

57 Marcel Breuer: ‘Wassily’ chair, 1925. Breuer emulated the lightness and strength of the bicycle frame in choosing tubular steel for the construction of his cantilever chairs.

58 K.J. Jucker and Wilhelm Wagenfeld: table lamp, 1923–4, inspired by a functional, geometric aesthetic.

59 Grete Schütte-Lihotzky: the ‘Frankfurt kitchen’, 1926. Optimum working areas are provided in a room only 3.5 by 1.9 metres (11½ by 6 feet). Note the swing stool, foldaway ironing board and built-in storage that reaches the ceiling. The light could be moved along on a rail.

Mies’s work represented the luxury end of the market, with emphasis on expensive materials. His design for the German pavilion for the Barcelona Exhibition of 1929 was unrestricted by cost or function, and he was able to experiment fully with this temporary structure.[60] The materials were ostentatious, including brass, marble and plate glass, and were used to maximum effect, as none of the surfaces was decorated. The structure consisted of a flat slab and intersecting walls, carefully placed to allow free circulation. The monumental leather-and-chrome Barcelona chair and stool designed for the Pavilion have since become classics of modern design, and remain in production today.

Mies used the same spatial concept for his next domestic commission, the Tugendhat House of 1930 in Brno, Czechoslovakia.[61] In the large living room the load is carried by slim cruciform columns covered in polished stainless steel and the interior space is divided by free-standing screens. The study is separated from the living area by a Malaga onyx partition and a semi-circular screen of Macassar ebony embraces the dining area. Mies was assisted in this as in other commissions by Lilly Reich, a German interior designer who had worked with him on the Barcelona Pavilion and ran the interior design courses at the Bauhaus during his period as director. The Tugendhat House design was typical of Mies and Reich in that it incorporated luxurious, plain materials, including silver-grey raw silk for the curtains, wool for the rug, tan and emerald-green leather and white kid for the upholstery. The flooring of white linoleum and tubular-steel furniture created an effect of stark elegance.

In 1927 Mies was involved with the first international statement of modern architecture when he directed the Deutscher Werkbund housing scheme at Stuttgart, known as the Weissenhofsiedlung. The city authorities provided finance for the Werkbund to design and build twenty-one model dwellings, and Mies invited fifteen leading modern architects to take part, including Gropius, Le Corbusier and the Dutch De Stijl architect J.J.P. Oud.

The exhibition put modern movement design on the map, presenting an international front for designers who shared the same aesthetic. Le Corbusier designed two dwellings for the site that expressed his ‘Five Points of Architecture’. These stipulated that the building should be supported above ground level by pilotis (free-standing structural piers of reinforced concrete); the interior should use a free plan, unrestricted by the need for supporting walls; there should be a roof terrace; the windows should be large, and form a continuous element of the exterior wall, and the facade should consist of one smooth surface. The interior of Le Corbusier’s flats consisted of a single space that could be divided to form bedrooms with the use of sliding partitions. The concept of an unrestricted internal space was basic to modern movement interior design.

German designers attempted to adapt to the needs of industry but Le Corbusier reversed the process by using machine production as an inspiration for his ‘one-off’ commissions. He founded the purist movement in 1918 with the painter Amedée Ozenfant (1886–1966) to celebrate a new, universal aesthetic. Le Corbusier and Ozenfant painted anonymous, mass-produced objects such as bottles and glasses in the belief that such everyday objects represented the ultimate in design, evolved over years of research and experiment. The same Darwinian process applied to architecture, and Le Corbusier sought out the simplest, most rational solution to any design problem.[62]

60 Mies van der Rohe: Barcelona Pavilion and the ‘Barcelona’ chair and stool, 1929. The building was commissioned to be the scene of the opening ceremony performed by the Spanish King and Queen.

61 Mies van der Rohe: dining room of the Tugendhat House, Brno, 1930. Cantilever armchairs of chromium-plated steel and silver-grey fabric, ‘Tugendhat’ chairs, were designed for the living area, and white kid leather-upholstered chairs, ‘Brno’ chairs, for the dining area.

Le Corbusier published his aesthetic theories in the periodical L’Esprit Nouveau, which he founded in 1920 with Ozenfant. He compared the elegant lines of contemporary cars with the Parthenon to demonstrate that the same aesthetic was in operation; that both represented ‘type-forms’, or the ultimate solution to a design problem. Whether designing furniture or replanning the whole of Paris, Le Corbusier was inspired by the same universal, absolute aesthetic. But the understanding of industrial design upon which Le Corbusier based his argument was erroneous. It has been shown that such ‘type-forms’ cannot exist, and that design changes in response to market forces.

Le Corbusier applied his theories to interior design at the 1925 Paris Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes. His small two-storey house, the Pavillon de l’Esprit Nouveau, challenged the nationalistic and decorative emphasis of the Exposition by including mass-produced furniture such as Thonet bentwood chairs.[63] Many of the items were industrially produced or intended as prototypes for mass production, for instance a table made by a hospital-furniture manufacturer. All the structural components such as doors and windows were based on a modular system. The effect of the interior was deliberately sparse, with the bare walls decorated only by Léger’s paintings. The main interest lay in the internal ordering, with a double-storey living area overlooked by a balcony providing a feeling of spaciousness on a very restricted site.

The Pavillon de l’Esprit Nouveau caused a great scandal at the Exposition, for it was so obviously a direct criticism of the majority of the exhibits, which celebrated the French cabinet-making tradition. Le Corbusier caused a further storm with his book L’Art décoratif d’aujourd’hui, published in the same year. Obviously inspired by Adolf Loos, he praised the new functional industrial design, and proclaimed that ‘Modern decorative art is not decorated’. Le Corbusier argued that the best designs were the simplest. He dismissed past styles as irrelevant to the 1920s, and derided the French designers’ love of luxurious materials, claiming that ‘Gilt decoration and precious stones are the work of the tamed savage who is still alive in us.’

Le Corbusier’s house designs of the period demonstrate the purist aesthetic. The interiors of Villa Stein at Garches (1927) and Villa Savoye at Poissy (1929–31) employ double-storey rooms, roof gardens, and ramps linking levels. They are planned as one flowing space rather than as given areas to be filled or embellished.[64] Le Corbusier’s furniture designed with Charlotte Perriand is integral, and is carefully placed to be admired aesthetically as sculpture.[65]

The work of the partnership was seen at the Salon d’Automne in 1929 with the ‘equipment of a dwelling’ layout. This consisted of a single large living area with other rooms leading from it. The totally modern effect was achieved through the extensive use of glass and metal. The floor and ceiling was covered in glass and the furniture was made of glass, leather and tubular steel.

62 Le Corbusier’s Maison Dom-ino, 1914, a ‘building type’ conceived by the architect as the basic component for industrially planned housing, demonstrating his abolition of internal supporting walls.

63 Le Corbusier: Pavillon de l’Esprit Nouveau for the Exposition des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, 1925. A double-height living room and mass-produced furniture such as Thonet bentwood chairs contrasted strongly with the rest of the French exhibits.

64 Le Corbusier: upper room and terrace, Villa Savoye, Poissy, 1929–31. The villa reveals Le Corbusier’s adherence to the open-plan ideal.

By 1932 the international reputation of the modern movement was established, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York held an exhibition showing plans and photographs of the work of Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius, together with the work of architects from Italy, Sweden, Russia, and in America. In the accompanying catalogue Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson aptly described the work as ‘International Style’, and characterized it as having flexible internal space and avoiding applied decoration. They warned against using colour on walls, adding, ‘there is no better decoration for a room than a wall of book-filled shelves’. The use of plants for interior decoration was also approved.

By 1932 a handful of European immigrants had brought modern movement design to America. The system of mass production that America had pioneered and which had inspired European designers had had little effect on American interior design until the European modern movement began to make its mark there. Rudolph M. Schindler (1887–1953) and Richard Neutra (1892–1970) had arrived from Vienna to design influential private houses in the European modern style. Neutra’s Lovell House in Los Angeles (1929), with its vast expanses of glass and free internal plan was considered worthy to be included in the Museum of Modern Art exhibition.[66]

65 Le Corbusier’s and Perriand’s best-known seating designs: the Chaise Longue of 1927 and (left) Grand Confort of 1928, both exhibited in 1929. Designed to express the machine aesthetic, they were never mass produced, and appealed only to a small élite.

Frank Lloyd Wright and other American designers could not accept the restrictions of the modern movement, rejecting its characteristic use of pilotis and regular blocks. In the 1930s Wright continued to develop his own personal style, which he considered more expressive of American values, culminating in Fallingwater at Bear Run, Pennsylvania (1934–6).[67] Built on a rocky hillside, the concrete structure cantilevers over a waterfall. The emphasis is on the organic, with rock-masonry walls, North Carolina walnut furniture and fittings, and huge windows creating a harmony between the natural beauty of the setting and the interior living space. A less industrial expression of the modern movement was also developing in Scandinavia. Finland, Sweden and Norway had not experienced the same rapid process of industrialization as Britain, Germany and America. When modern movement principles began to affect Scandinavian design around 1930 there was still a strong craft tradition in existence. Whereas in Britain arts and crafts products were too costly for most of the population to buy, Scandinavian hand-crafted goods could be bought by the majority. The simplicity of modernism was fused with folk design to produce Scandinavian modern. Furniture by Bruno Mathsson, Børge Mogensen, Kaare Klint and Magnus Stephenson was exported to America and Britain from the 1930s onwards, the softly curving lines and warmth of the woods providing a popular alternative to the coldness of German tubular steel.

66 Richard Neutra: staircase, Lovell House, Los Angeles, 1929. An early example of European modernism in America. The house has a double-height living room and built-in seating. For the light on the stair-wall Neutra chose to use an off-the-shelf industrial component: a Model A Ford headlight.

67 Frank Lloyd Wright: living room, Fallingwater, Bear Run, 1934–6. The vast living area has extensive windows to integrate indoors and outdoors, and a natural stone floor.

68–9 Alvar Aalto: lecture hall (top), Viipuri Library, 1935. An undulating wooden ceiling and curved plywood furniture typify the more humanistic Scandinavian approach to modernism that was to be crucial for post-war interior design. Aalto’s chair (bottom).

The best-known exponent of Swedish modern abroad was the Finnish architect Alvar Aalto (1898–1976). Aalto’s Sanatorium at Paimio (1933) and the Viipuri Library (1935), both in Finland, use brick and wood where his German contemporaries would have used concrete.[68] The undulating wooden ceiling of the lecture hall in the Viipuri Library is a superb example of Aalto’s humanistic architecture. Aalto experimented with bent plywood and laminates in his furniture designs of the period to achieve a modern but warm and human effect, in harmony with his interiors.[69]

As the modern movement became accepted by the international avant-garde it acquired new political connotations. The Bauhaus had been closed down in 1932 by the Nazi-controlled Weimar council. Mies van der Rohe attempted to keep the school alive by running it as a private institution in a disused factory in the Berlin suburbs, but this too was closed by the Nazis in 1933. For the extreme Right in Germany, modern art and design represented an international, Jewish contamination of German ‘Volk’ culture. During the late 1930s in Germany the vernacular or the classical were the only styles deemed suitable for the expression of Third Reich ideology. Hitler’s official architect Albert Speer recreated the glories of past empires in his monumental interiors, designed to intimidate and overpower.

In Italy the situation was reversed and the Fascists adopted architettura razionale as a Party style.[70] The Casa del Fascio at Como (1932–6) by Giuseppe Terragni (1904–1943) is a building in the International Style, with white walls and specially designed tubular-steel furniture. The link between modernism and the Right in Italy stems from the futurist movement of 1914–17, which celebrated the machine in painting, poetry, and the architectural drawings of St Elia, while welcoming the First World War as ‘the hygiene of society’.

During the inter-war years the British looked on past traditions with affection, reluctant to acknowledge the nation’s decline as a world power. The modern movement was slow to influence British interior design because it was regarded as foreign and left wing – an impression not entirely unfounded in view of the history of the Bauhaus – and a radical image was courted by British modernists. The powerful ideology of the ‘British home’ and the continuing influence of arts and crafts values almost guaranteed modernism’s unpopularity. A core of convinced modernists attempted to persuade the British public and industry to accept the modernist creed, hindered no doubt by a proselytizing tone, and also by the growing popularity of a rival style that had reached Britain by way of Hollywood, to be considered in the next chapter.

70 Giuseppe Terragni: Conference Room, Casa del Fascio, Como, 1932–6.

The British Design and Industries Association (DIA) had been founded on the model of the German Werkbund in 1915. Founder members, including the London furniture retailer Ambrose Heal of ‘Heal’s’, the director of the Dryad furniture-manufacturing firm Harry Peach, and Heal’s cousin Cecil Brewer, strove to educate the national taste. One of the DIA’s propaganda exercises was the 1920 exhibition, ‘Household Things’, which included furniture, textiles, ceramics and glass in eight room settings. It is clear from this exhibition and from the DIA publications that the Association had a broader view than its German counterpart of what constituted ‘good design’. The DIA Yearbooks, modelled on the German example, contained specimens of the Georgian Revival, and the functional aesthetic was reserved for industrial products. The DIA typified the British version of international modernism: diluted Scandinavian modern and arts and crafts traditionalism. This style can be seen in the work of the furniture manufacturer and designer Gordon Russell (1892–1980), whose reconciliation of the three influences laid the foundation of 1950s British interior design.[71]

Fleeing Nazi Germany, Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer and the architect Erich Mendelsohn (1887–1953) all joined the avant-garde community based around Parkhill in Hampstead, London, before leaving for the United States. British commissions for such designers were few. Gropius designed the Village College at Impington before taking up a post at Harvard. Breuer stayed from 1935 to 1937, during which time he designed bent-plywood furniture for Isokon. Mendelsohn set up in partnership with the Russian-born Serge Chermayeff (1900–1996) to design the De La Warr pavilion at Bexhill-on-Sea, Sussex (1936). Modern interior design in Britain was significantly forwarded after the appointment of designer Raymond McGrath (1908–1977) as Decoration Consultant for Broadcasting House, the new BBC headquarters. McGrath was himself an eclectic designer, and he employed Serge Chermayeff and modern architect Wells Coates (1895–1958) on his team. The interiors of the studios by Coates were outstandingly simple and functional, and used modern materials like tubular steel. The same qualities distinguished the designs for London Underground stations commissioned by Frank Pick, a founder-member of the DIA and head of the London Passenger Transport Board, from the architect Charles Holden. More than thirty tube stations were designed on modern movement principles and were accordingly easier to use, more brightly lit, and presented a clear corporate image.

71 Gordon Russell: dining room, 1933–6. Furniture in Japanese chestnut and walnut manufactured by Gordon Russell Ltd demonstrates how few concessions British design made to European modernism. The carpet is designed by Marian Pepler. (Russell Room, Geffrye Museum, London).

72 Charles Holden: London Transport Underground Station, Leicester Square, 1935. Clear design on modern principles.

Domestic modern design was brought before the public at the ‘Exhibition of British Industrial Art in Relation to the Home’ in 1933. Wells Coates’s ‘Minimum Flat’ was inspired by the topical problem of living in a small space. It contained a model kitchen, bedroom, living room and bathroom in a strictly functional modern style. The response of critics and public alike was that the Flat showed that modernism could be successful in the design of a kitchen or bathroom where efficiency was important, as well as for new types of interior such as Underground stations and broadcasting studios, but that it was not appropriate for the sanctuary of the British living room.[72]

During the late 1930s America became the focal area for modern architecture and design. Architect-designers including Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, Marcel Breuer and Moholy-Nagy began to work and teach there, the latter to found the ‘New Bauhaus’ in Chicago in 1937. The modernists’ achievements were to be greatly admired and emulated, particularly after the Second World War. During the 1920s and 1930s, however, there was a rival development in interior design that enjoyed far wider popularity in France, America and Britain – that of Art Deco.