At the 1910 Bruxelles Exposition Universelle the French had exhibited interiors in the art nouveau style while the German designers showed something entirely new. Room settings by Munich-based designers such as Professor Albin Müller were simple and geometrically ordered, and showed the influence of Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Although critics referred to the austerity, restraint and peasant origins of many of the German exhibits with some disdain, it was clear that they represented a progression from the outdated art nouveau.

Later in the same year the French sense of a German challenge was confirmed at the Paris Salon d’Automne. This exhibition had been established in 1903 as a fine art showcase, but from 1906 design was included, and the 1910 exhibition featured work by Munich decorators linked with the Deutscher Werkbund, including Karl Bertsch, whose lady’s bedroom was criticized by French design experts for its lack of femininity and shoddy workmanship. It nevertheless proved a popular success, and French designers were galvanized to take action to maintain the position as leaders of taste that they had enjoyed since the eighteenth century. The plan for an international exhibition concerned solely with design began to take shape.

The term ‘art deco’ derives from the title of this international exhibition. Because of the First World War and its aftermath the Paris Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes did not take place until 1925. The exhibition and the type of French work on display grew out of an effort to modernize French interior design in which, unusually, architecture took second place. Both art nouveau and the modern movement had been architecturally based, with interior design regarded as an inferior art. Now interior design provided the focus.

Classical inspiration, the use of smooth surfaces to envelop the three-dimensional form, love of the exotic, sumptuous materials and repeated geometric motifs characterize the art deco style. Although the style did not gain widespread recognition until 1925, its source was in the pre-war work of France’s leading designers. The classicized forms of the finest French furniture of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries had been taken as models to cleanse design of the nightmarish excesses of art nouveau.

Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann (1879–1933) was the acknowledged leader of French interior and furniture design of the period 1918 to 1925. He worked within the conventions of French eighteenth-century tradition. His architectural detailing and the proportions of his interiors were classically inspired, and his furniture designs often incorporated features associated with the Empire period such as tapered, fluted legs and drum-shaped tables. The lines of the furniture were frequently picked out with a thin ivory inlay, and delicate ivory caps, called sabots, covered the feet. The quality of workmanship was no less reminiscent of the eighteenth century. In common with many French art deco designers, Ruhlmann used only the rarest of materials, including lizard skin, shagreen (sharkskin, or galuchet), ivory, tortoiseshell and exotic hardwoods.

The market for Ruhlmann’s work was necessarily restricted to the wealthy, or to such clients as the Paris Chamber of Commerce and the cosmetic firm of Yardley. To emphasize their exclusiveness, from 1928 each of his pieces was given a serial number in an edition, and a certificate with the number and Ruhlmann’s signature accompanied each purchase.

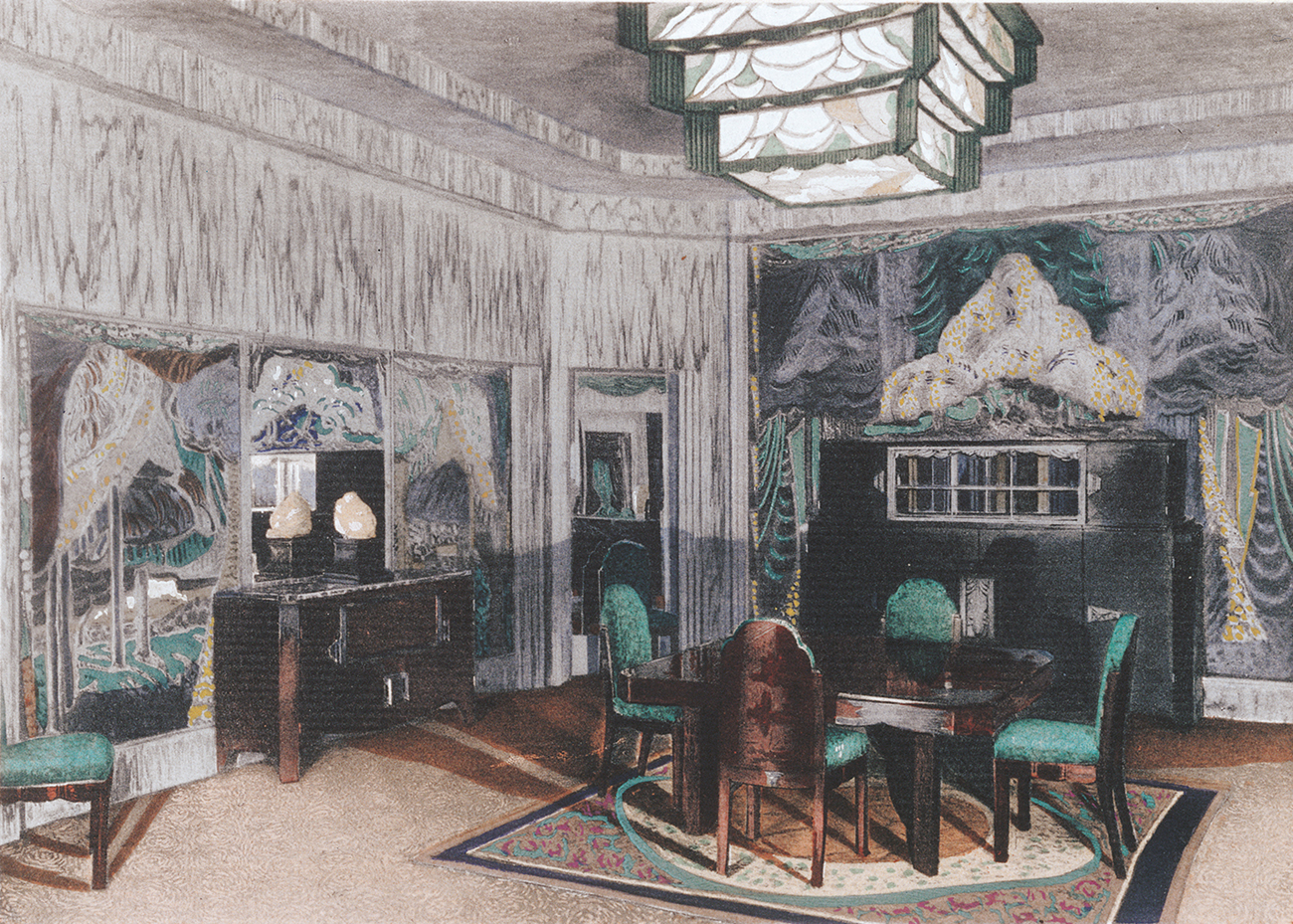

Ruhlmann’s work was displayed at the 1925 Exposition in Le Pavillon d’un Collectionneur, a series of rooms based on Ruhlmann’s own house.[73] The dining room has the classical elegance associated with Ruhlmann with chairs loosely based on the eighteenth-century gondole type. The vast Grand Salon of the Pavilion shows Ruhlmann working at his best. It features boldly patterned wall-coverings, a huge chandelier and classical detailing, including the entablature running around the room at the point where the walls join the ceiling.

The designers André Groult (1884–1966) and Paul Iribe (1883–1935) also used the inspiration of past French models to create a new style. Iribe was an important figure in the world of French fashion who had designed an apartment for the collector of modern art and couturier Jacques Doucet in 1912 using eighteenth-century models.[76] Groult combined the classic outlines of Louis XVI furniture with art deco features such as formalized baskets or garlands of flowers, tassels, ropes and feathers. His woman’s bedroom shown in the Pavillon de l’Ambassade Française in the 1925 Exposition contained shagreen furniture such as a bombe-shaped chest of drawers and gondole chair upholstered in velvet.[74-5] The sensuous curves of the chest of drawers evoke the room’s intended inhabitant.

73 Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann: Grand Salon, Le Pavillon d’un Collectionneur, Exposition des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, 1925. The painting Les Perruches by Jean Dupas over the mantelpiece was a specially commissioned mural that later featured in reproduction in the sets of Cecil B. de Mille’s Dynamite (1929).

Art deco designers were not inspired solely by past French styles. A hallmark of the style is the sunrise motif, seen on the head and foot of Groult’s bed. The motif was probably derived from ancient Egyptian art, a popular source of inspiration after the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922. The geometric emphasis of much art deco was derived from cubism, the avant-garde movement in painting that lasted from c. 1907 to 1914. Led by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, it sought to deconstruct the Renaissance way of representing three dimensions on a two-dimensional surface. The new analysis of visual reality resulted in fragmented, angular forms which art deco designers assimilated into their work.

74–5 André Groult: Chambre de Madame, Pavillon de l’Ambassade Française, Exposition des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, 1925. Velvet upholstery and a curved, shagreen-covered chest of drawers conjure up an ambience of femininity. The stool on the right of the lower image is by Ruhlmann.

A direct link between cubism and interior design appeared in 1912 at the Salon d’Automne, when the predominantly traditional designers André Mare (1885–1932) and Louis Süe (1875–1968) collaborated with the minor cubists Roger de la Fresnaye, Raymond Duchamp-Villon and Jacques Villon on the ‘Maison Cubiste’. The collaboration continued with the foundation of the decorating firm Compagnie des Arts Français in 1919 by Süe and Mare.

One of the most important inspirations for the cubists had been non-European art, and art deco designers used the same source to create the exotic ambience so characteristic of the style. The designer Pierre Legrain (1889–1929) reproduced non-Western furniture in fashionable materials. For example, the curved seat of an Ashanti stool can be identified in his exhibit at the Salon des Artistes Décorateurs of 1923, and his chair of 1924 in palmwood veneer and parchment is based on an Egyptian model.

76 Couturier Jacques Doucet’s villa at Neuilly, 1929. Art deco motifs in the room illustrated include stepped ziggurat shapes on the ceiling and a desk and African tribal-inspired stool (left) by Pierre Legrain.

A taste for the exotic was also inspired by the stage designs of Léon Bakst for the Ballets Russes. Sergei Diaghilev’s Sheherazade was seen in Paris in 1908, and the vivid colours and evocation of a distant, exotic land only heightened the contemporary fashion for Persian and Arabian themes, prompted partly by the French translation of The Thousand and One Nights’ Entertainment between 1896 and 1904. The fashion for the oriental was also apparent in Britain and America with the craze for large tasselled cushions of varying shapes, covered in sumptuous fabrics. In June 1920 the new magazine concerned with British middle-class interiors, Ideal Home, described ‘The Indispensable Cushions: How To Make Them and Where To Put Them’. They were used in strongly coloured rooms, often black and red, with red lacquer-work furniture and China pagoda lamps.

Avant-garde painters were experimenting with the possibilities of colour at this time, and had a marked influence on art deco. Orphism, developed in Paris before the war by Sonia and Robert Delaunay, had liberated colour from the formal concerns of easel painting. Sonia applied the experiments of orphism to design during the 1920s, decorating their apartment with square armchairs covered in geometric textiles and matching rugs, and walls hung with beige-patterned linen.

The Fauves, or ‘Wild Beasts’, were a group of painters including Matisse, Derain and Vlaminck whose work between 1905 and 1908 used vivid colours in shocking contrasts. Such colour combinations were adopted by designers as a reaction to the insipid pastels of art nouveau. No designer exploited the mystical East or strong colours better than Paul Poiret (1879–1944). Originally a haute-couture fashion designer renowned for liberating women from the corset, Poiret set up his own interior decoration studio, the Atelier Martine, in 1912 after seeing the work of the Wiener Werkstätte. The fauve painter Raoul Dufy (1877–1953) designed bright, fresh fabrics for the Atelier Martine from its foundation until 1912, when he left to work for the giant textile mill Bianchini-Férier. Designs were also supplied by the École Martine, a school for young working-class girls who produced the naive and colourful style of design that Poiret so admired. The Atelier successfully designed and sold printed fabrics, wallpapers, ceramics, rugs and embroideries, as well as undertaking complete interior-design commissions, including the decoration of Poiret’s own couture house. The interiors relied for their effect on brightly coloured decorations of trees and flowers painted on the walls, with low furniture and shimmering or boldly patterned fabrics.[77]

77 Paul Poiret: bedroom, 1924. Exotic wall decorations and a low bed with silk tasselled cushions evoke an atmosphere of the orient. To complete the fantasy a snail shell has strayed into the centre of the ceiling.

Poiret made no distinction between furnishing and clothing textiles, and this crossover between women’s high fashion and interior design is typical of art deco. The style was conceived in response to the challenge of rational, functional, Austro-German design, perceived as masculine, and was identified with frivolity, irrationality and ‘mere’ decoration, regarded as feminine, a gender stereotype inherent in Western culture.

French women’s fashion formed a dominant part of the 1925 Exposition. This was partly due to the disappointing foreign contribution. Germany did not take part, claiming that the invitation had arrived too late. America declined to contribute, as it was felt by Herbert Hoover, the Secretary of Commerce, that she could not offer examples of work that were of the ‘new and really original inspiration’ which the exhibition authorities had stipulated. The British showing was weak. Designed by Easton and Robertson and decorated by Henry Wilson, a vaguely Moorish structure surmounted by a model sailing ship did little to impress the French. The 1925 Exposition came only a year after the Empire Exhibition at Wembley, and Britain could afford no more than a token contribution.

78 Paul Follot: Grand Salon, designed for Pomone of the Paris department store Bon Marché and shown at the 1925 Exposition. The Paris stores played a major role in the development of art deco design.

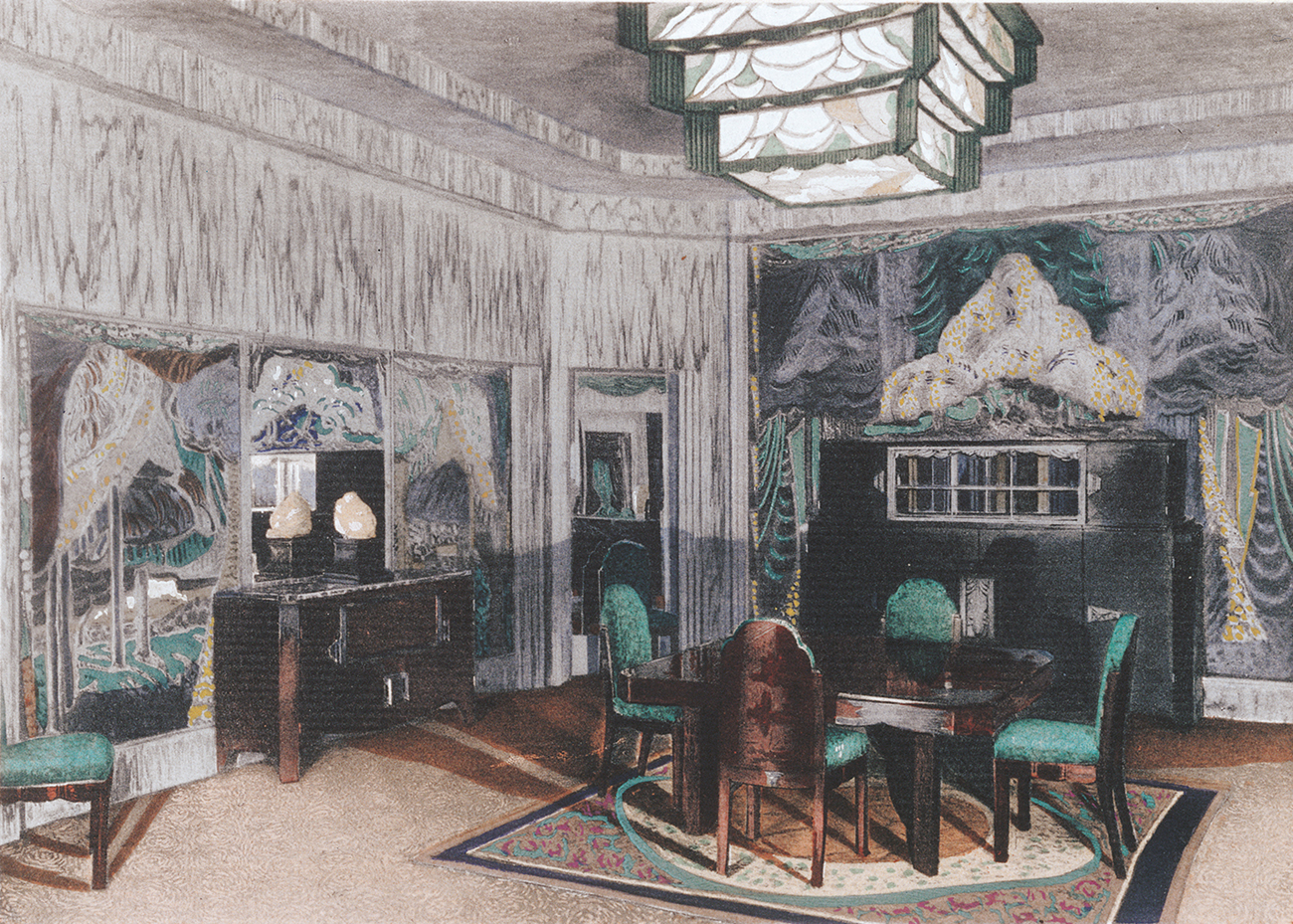

Most of the Exposition was made up of the French pavilions, with leading Parisian department stores making a strong showing. Many of the stores had established interior decoration departments, and their skills were displayed at the Exposition in a number of room settings in the art deco style. Paul Follot (1877–1941) became the Director of Pomone for the store Bon Marché in 1923 and Maurice Dufrêne (1876–1955) headed La Maîtrise at the Galeries Lafayette from 1921.[78] Follot’s Grand Salon for Bon Marché uses a bold contrast of angular patterns and stylized flowers on the carpet, panels of the display cabinets and entablature. Art deco interiors rarely incorporated paintings, as the decorations themselves were sufficiently rich. The one exception to this was the mural painting.

Murals formed an essential part of the luxurious Art Deco interior. Ruhlmann used a large work by Jean Dupas (1882–1964), Les Perruches, in the Grand Salon of ‘Le Pavillon d’un Collectionneur’. This was typical of Dupas’s work with its combination of stylized figures of women and a highly colourful background of birds, fruit and flowers. Jose-Marie Sert (1874–1945) was another such mural painter, whose commissions were on a vast scale, and who decorated ballrooms for high-society hosts. Exotic scenes were often painted in black on silver or gold leaf backgrounds, reflecting Sert’s early involvement with theatrical design.

Exotic fauna and flora also figured in art deco metal furniture and fittings. Armand-Albert Rateau (1882–1938) created bizarre interiors in which strange bird shapes in bronze supported tables and even formed the bath taps.[79] The apartment he designed for the couturier Jeanne Lanvin included a low table with patinated bronze birds supporting a marble top, set in a bedroom hung with embroidered blue silk. Edgar Brandt (1880–1960) was the leading French metalworker of the 1920s, and frequently used animals, birds and flowers in his designs. The decorative panel ‘Les Cigognes d’Alsace’ of 1923 features three storks in an octagon surrounded by a garland of flowers, with radiating sunbeams and spiral motifs. Copies of the panels were used to decorate lifts at the new Selfridges department store in London in 1928. Brandt contributed extensively to the 1925 Exposition, designing the wrought-iron gates in the Pavillon d’un Collectionneur.

Designers at the Exposition worked as traditional French ensembliers, ordering all aspects of the interior to create a complete work of art, symbolically expressive of the intended inhabitant. Art deco designers opposed modern movement doctrine because it neglected individuality and the decorative aspect of interior design which they felt to be so vital. Le Corbusier’s display at the Exposition showed that modern movement architects believed in a universal style for all interiors, whether private or public.

79 Armand-Albert Rateau’s bedroom for the couturier Jeanne Lanvin, 1920–2. Embroidery of gold-and-white marguerites and an alcove bed create an atmosphere of refinement and luxury. Note the patinated-bronze and marble table with legs in the shape of birds. (Room reconstructed in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris).

This position altered after the 1925 Exposition as a new generation of French designers began to use the modern movement aesthetic in their work. The ‘moderne’ designers, as they came to be known, upset the old guard and Paul Follot in particular with their apparent neglect of French decorative traditions.[80] The career of Eileen Gray (1878–1976) demonstrates this trend. In 1920 she designed an apartment for the milliner Suzanne Talbot in which animal skins, an armchair upholstered in salmon-pink with front legs modelled on two rearing serpents, a piroque (canoe) sofa in patinated bronze lacquer with silver-leaf decoration, and a lacquer-work brick wall leading from the gallery to the bedroom created the exotic and sumptuous atmosphere typical of art deco. In 1922 she opened her showrooms in Paris, the ‘Galerie Jean Désert’, to sell exclusive art deco handmade rugs and lacquer-work screens. As a result of the influence of the modern movement in the late 1920s, she became interested in architecture and abandoned her earlier highly decorative style. Her later designs were for practical tubular-steel, glass and wooden furniture. Her Transat chair of 1927, for example, is box-shaped and has chrome-steel fasteners connecting the black-lacquered frame.

Other art deco designers to follow a similar path included members of the Union des Artistes Modernes, founded in 1929 by Pierre Chareau, René Herbst, Robert Mallet-Stevens and François Jourdain among others. This group welcomed new industrial materials and modern movement ideas, in opposition to the more reactionary Société des Artistes Décorateurs. Chareau’s ‘Maison de Verre’, 31 Rue Saint Guillaume, Paris, used standardized industrial components, including glass bricks, to create entire walls within a metal frame.[81] Although this might appear to embody the aims of the modern movement, it is, rather, the fashionable adaptation of the aesthetic. Designers like Chareau (1883–1950) incorporated modern materials and tubular-steel furniture into their designs to provide a modish effect, and cared little for the aims and ideals of Le Corbusier or the Bauhaus.

80 Art deco modulates into the moderne. Background, left, Eileen Gray’s pink chair with legs modelled on two rearing serpents, designed in 1920, the epitome of art deco. Two more functional Bibendum chairs of 1929 and a tobacco-coloured sofa, also by Gray, are moderne. Gray’s former dark and sultry apartment for milliner Suzanne Talbot has been remodelled by Paul Ruaud in 1932 with a glass floor and clinical white-painted walls.

81 Pierre Chareau: the ‘Maison de Verre’, Paris, 1932. Huge metal supports, glass bricks and non-slip rubber flooring are the setting for art deco furniture by Chareau.

The French authorities were just as eager to exploit the prestige of French design during the 1930s as they had been during the previous decade. In 1935 the maiden voyage of the largest passenger liner in the world, the Normandie, provided the opportunity for France to display the best work of her designers.[82] René Lalique (1860–1945) had experimented with the decorative possibilities of glass from the turn of the century, making scent bottles, car mascots and interior fittings. He designed glass panels, two huge chandeliers and standard lights for the 305-foot (92-metre) main dining room of the Normandie.[83] Contemporary design was officially encouraged in France, and this contributed towards the success of art deco as an international decorative style. The picture was very different in Britain, where there was no such national pride in the achievements of interior designers.

82 Glass by René Lalique for a dining room designed by the Rouen painter Raymond Quibel, displayed at the Exposition des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, 1925. The furniture is exotic palissander.

83 First-class dining room of the passenger liner Normandie, 1935, with Lalique’s vast chandeliers, thirty vertical light-panels and twelve fountains of glass supported on pedestals, a glittering showcase of French design.

Art deco and the moderne, like modernism, were slow to influence British design. After the First World War a prevailing mood of insecurity was countered by a revival of interest in the Elizabethan period, Britain’s great age. This was reflected in interior design with a mania for panelled rooms and mock-Tudor electric light fittings. The pages of British publications such as The Studio, Ideal Home and The Studio Yearbook of Decorative Art for this period are filled with images of traditional English cottages with cosy interiors, supplied with mock-Jacobean furniture and chintz upholstery – revivals that owed as much to the national mood as to the lingering influence of the arts and crafts movement.

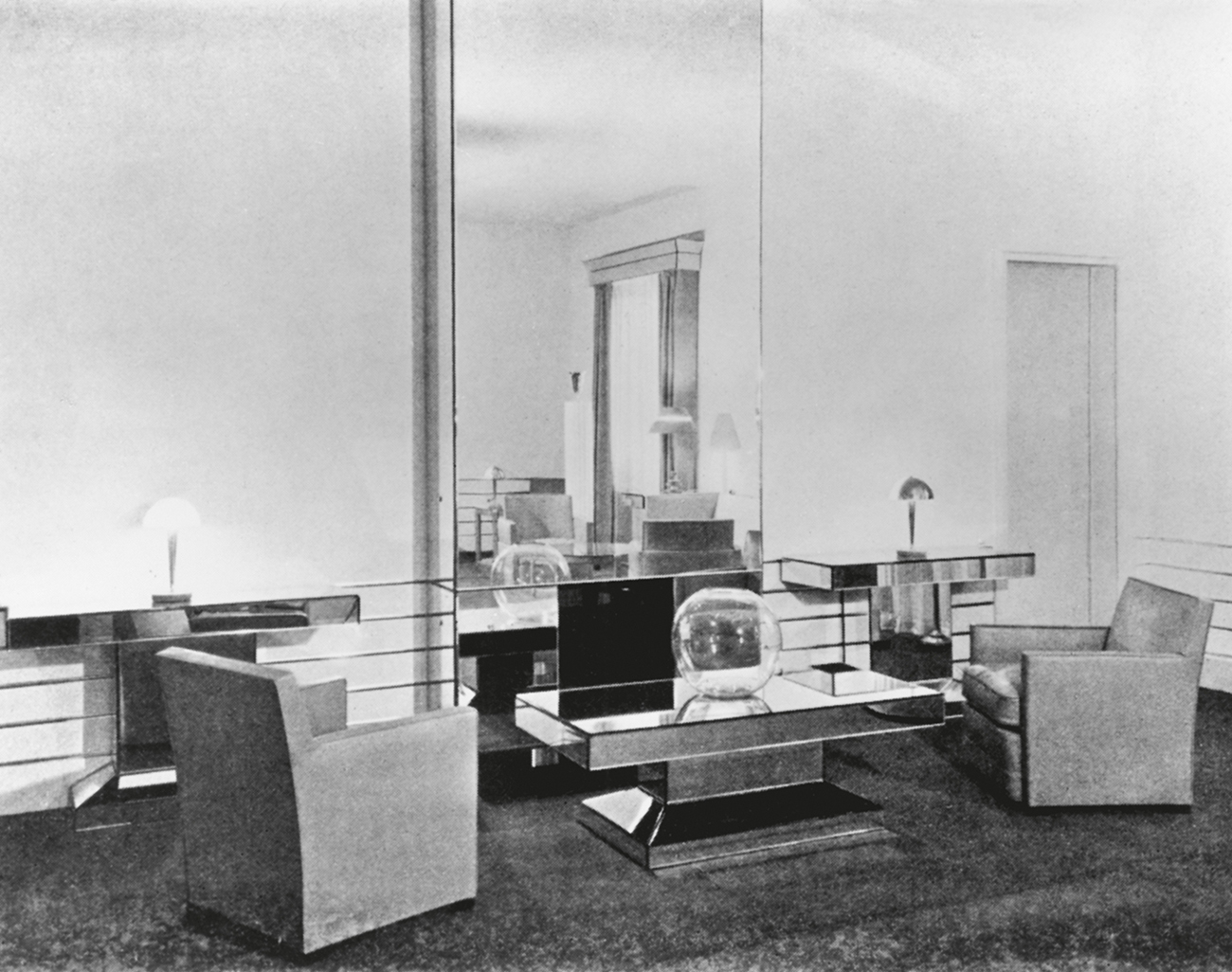

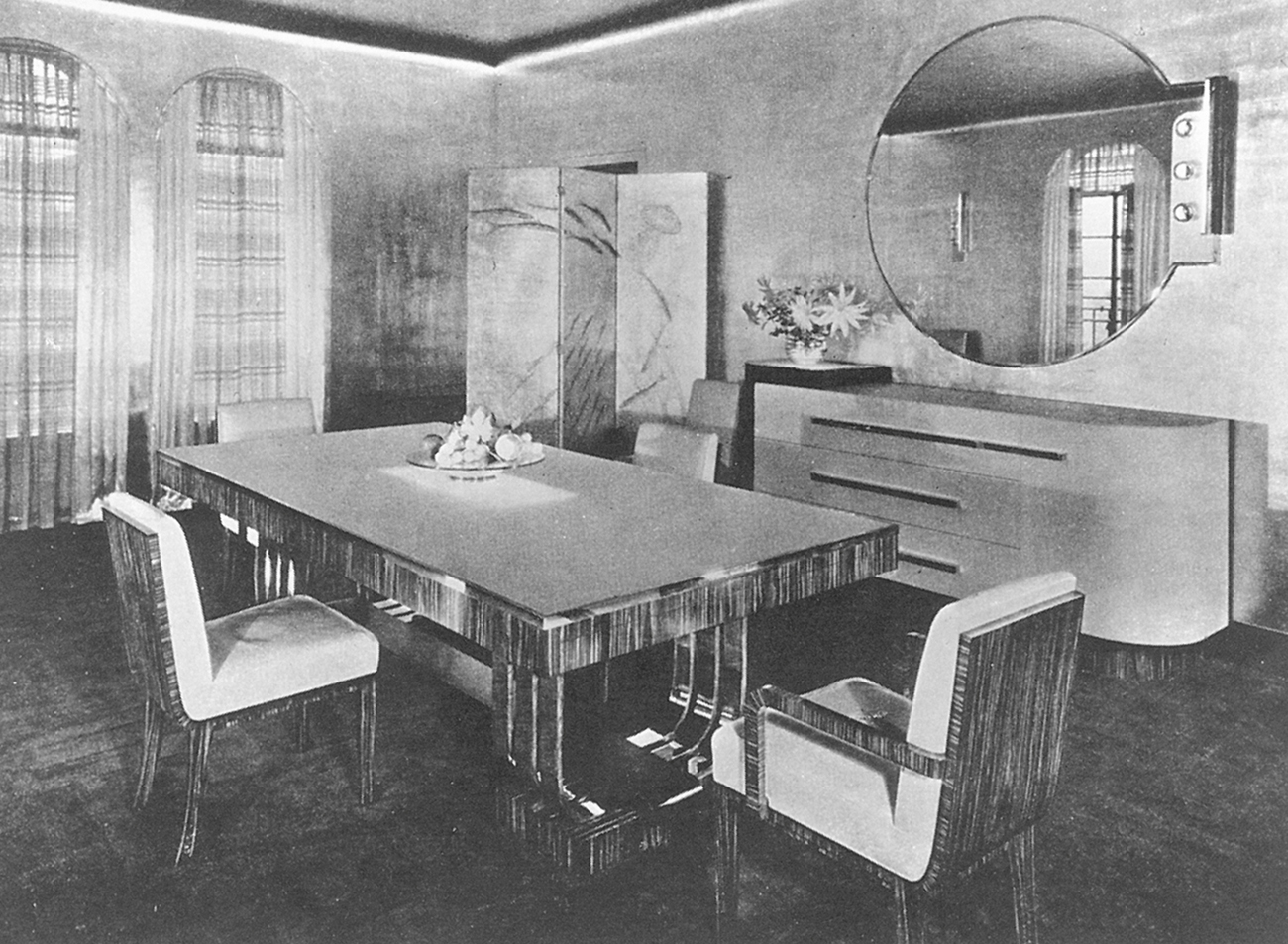

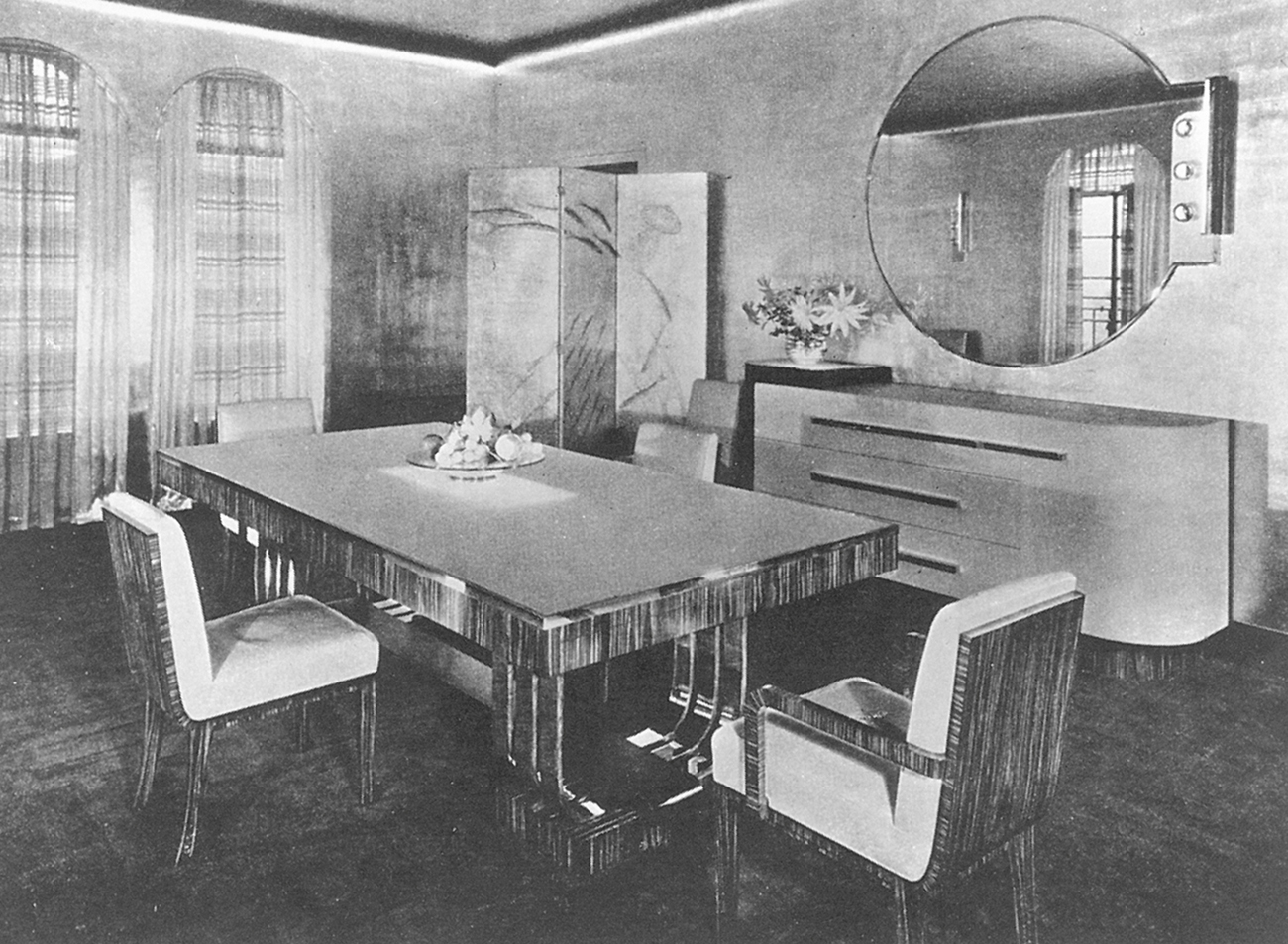

In 1911 Marcel Boulestin had opened a decorating shop called ‘Decoration Moderne’ in Elizabeth Street, London, supplying textiles and wallpaper by Studio Martine, André Groult and Iribe, but this had little effect on majority taste. The Studio magazine criticized much of the 1925 Exposition as pursuing novelty for its own sake. French progressive furniture was first seen in London in 1928 when the decorating firm of Shoolbred’s held an exhibition of work by DIM (Décoration Intérieure Moderne), a company that had been founded in 1919 by René Joubert. In the same year the furniture company Waring & Gillow opened a Modern Art Department in London for the sale of French and British furniture under the direction of Paul Follot and Chermayeff. Chermayeff’s sixty-eight room settings for the exhibition reflected Parisian taste for veneered and highly polished furniture, patterned floor coverings and geometric motifs. Chermayeff created a similar effect in the living room and dining room of his own home, which included such ‘moderne’ features as tubular-steel chairs.[84] In this and his architectural commissions he was able to combine his knowledge of the modern with French developments to produce a successful blend. From 1928 onwards, British design generally became less insular as contemporary trends from the Continent were seen and discussed.

84 Serge Chermayeff: dining room of his own house, London, 1930. A moderne combination of tubular steel and highly polished veneer, rare in 1930s Britain.

The chief source of the moderne inspiration, however, was America. Isolated from Europe during the 1914–18 war, Americans first learned of advances in design from the 1925 Paris Exposition. Up to this point only styles evoking past periods had been used. There was the American arts and crafts movement which had survived the First World War, with the Mission Revival (1890–1915) and the Spanish Colonial Revival (1915–1930) forming a part of this trend. America regarded her achievements in the decorative arts with such small esteem that, while she did not participate in the 1925 Paris Exposition, a large contingent of more than one hundred American delegates attended, representing every design field. Most were favourably impressed by what they saw. The new French style was disseminated in America by magazines and museum and store displays. In 1926 the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, organized a touring exhibition of design artefacts, and established a permanent gallery for the display of furniture bought at the Paris Exposition. New York department stores, most notably Saks, Fifth Avenue, Macy’s and Lord and Taylor, set up displays of contemporary French furniture after 1925. No fewer than thirty-six museums and department stores held exhibitions of art deco throughout America during the next three years.

Art deco was enthusiastically received because it was new, not retrospective, and America, as a comparatively young country, was anxious to establish a distinctive design identity to match her economic and industrial presence. America had led the world in methods of mass production and marketing manufactured goods. Art deco style’s bright surfaces and abstract patterns well expressed American aspirations, not least in the suggestion of machine production contained in the precise repetition of geometric motifs. Ironically, the ease with which art deco was assimilated could also be explained by the continuing authority of Paris as a leader of taste.

The Viennese-born designer Joseph Urban (1872–1933) had established the Wiener Werkstätte of America, opening a showroom on Fifth Avenue, New York, to produce finely crafted, geometrically based furniture in the spirit of the Austrian prototype.[85] The Werkstätte only lasted from 1922 to 1924, but Urban’s designs for simple chairs with repetitive square decoration made the Americans more receptive to art deco. Urban used art deco for the design of pavilions at the 1933 ‘Century of Progress’ exhibition in Chicago, including the Travel and Transport Building, which used the rising sun motif combined with the stepped ziggurat shape of the style. Art deco was soon adopted for the interiors of buildings as diverse as modest hotels in Miami Beach and skyscrapers in New York City. The skyscraper had emerged as a building type in New York during the 1870s, and had flourished in Chicago during the next decade. During the inter-war years skyscrapers were built at a great rate in every major American city. The designs for the foyers of these buildings needed to measure up to their imposing exteriors.

Ely Jacques Kahn (1884–1972) was the leading designer of art deco skyscraper entrance lobbies, including the Lefcourt Clothing Center, 120 Wall Street, and the Bricken Building, 111 John Street, of the late 1920s. The interiors of the Chrysler Building (1928–30) and the Empire State Building (1930–32) are resplendent with art deco motifs: the entire surface of the elevator doors of the Chrysler Building is veneered in light amber and dark brown woods in a geometric lotus design. The lighting fixtures, signs and floors are all decorated with stylized flowers and geometrical shapes taken straight from the 1925 Exposition.[86] Another important skyscraper, the Chanin Building, on 42nd Street and Lexington Avenue, New York, was built during 1928–9 as a monument to the success of property developer Irwin S. Chanin. The interior decoration was overseen by Jacques Delamarre, head of the huge Chanin Construction Company.[87] The opulent Executive Suite washroom, created for Irwin S. Chanin, was tiled in cream, gold and green with a gold-plated sunburst over the geometrically engraved glass shower doors.

85 Joseph Urban: ‘Man’s Den’ for the ‘Architect and the Industrial Arts’ exhibition, New York’s Metropolitan Museum, 1929. Severe geometrical design sparked by the patterned rug.

86 Lobby of the Chanin Building, New York. Plaque ‘Endurance’ and art deco metal grille by René Paul Chambellan and Jacques Delamarre, 1928–9. The plaque is one of a series ‘New York – City of Opportunity’.

87 Washroom for Irwin S. Chanin, 52nd storey, Chanin Building, New York, 1928–9. Note the art deco sunburst over the engraved-glass shower doors.

88 Light fitting of cast aluminium inspired by contemporary skyscraper design, Weary & Alford, City Hall, Kalamazoo, c. 1930.

French art deco also strongly influenced the interiors of the Netherland Plaza Hotel, Carew Tower, Cincinnati, of 1931 by Walter W. Ahlschlager (recently restored). The lavish Hall of Mirrors and Palm Court have ornamental metalwork balustrades in the style of Edgar Brandt, with exquisite glass and metal lamps. The luxurious foyer of the Banking Hall of the Irving Trust Company, New York (1932), was one of the last grand interiors to be designed in a purely art deco manner in America.[89] The vast walls are decorated with a reflective mosaic in red shading to orange. The vertical line is emphasized by the panels that divide the walls, and by the perpendicular heating vents.

89 Foyer of the Banking Hall of the Irving Trust Company, New York City, by Ralph Walker of Voorhees, Gmelin & Walker, 1932.

90 Walter Dorwin Teague: sitting room for La Société Matford, Paris, late 1930s. The verticals of the skyscraper lobby give way to streamlining.

The vertical so characteristic of art deco was to give way to the horizontal line during the 1930s, as another design trend emerged in America that was to combine elements of art deco, the International Style and French moderne. This was streamlining, or the American moderne.[90]

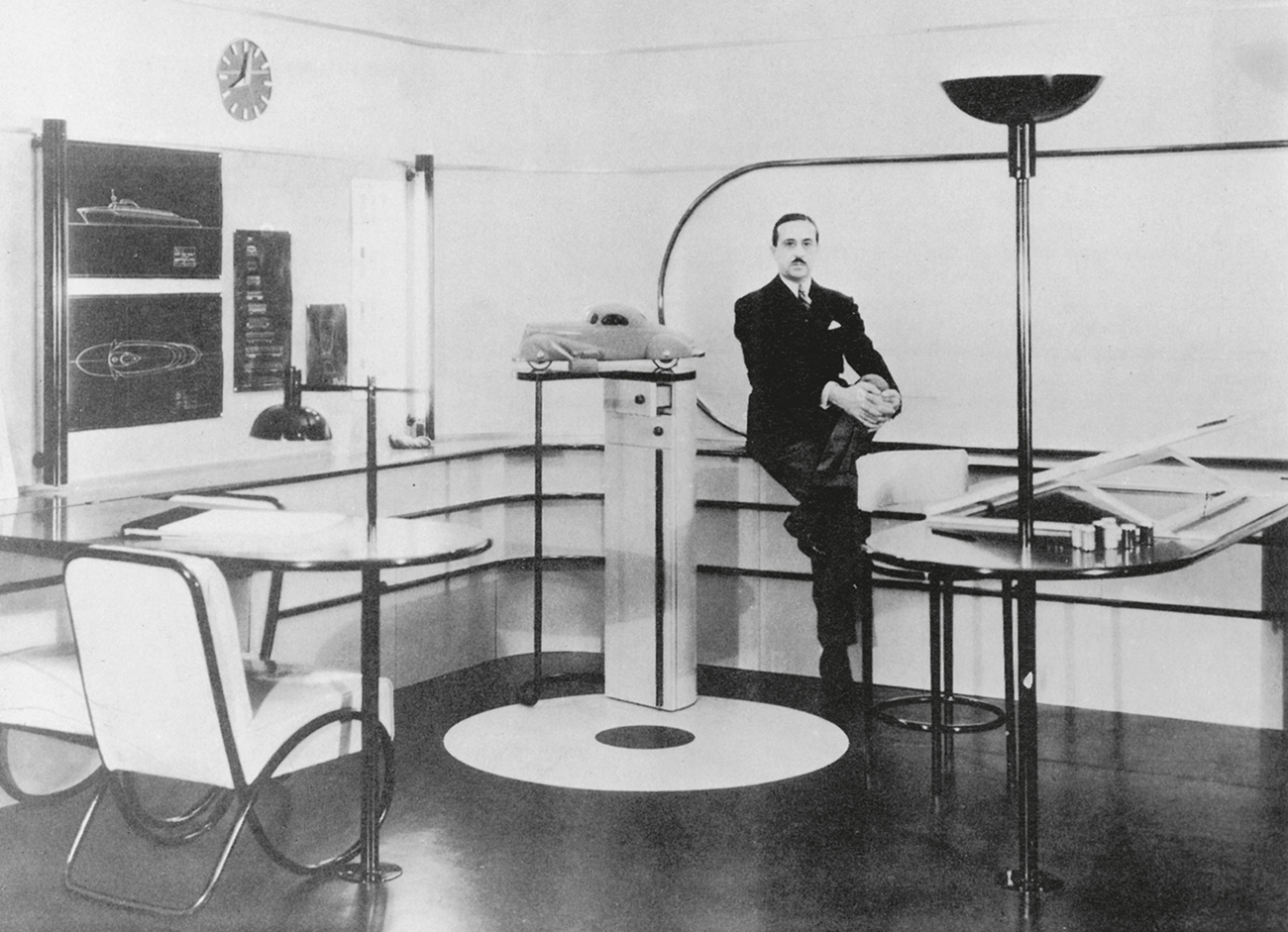

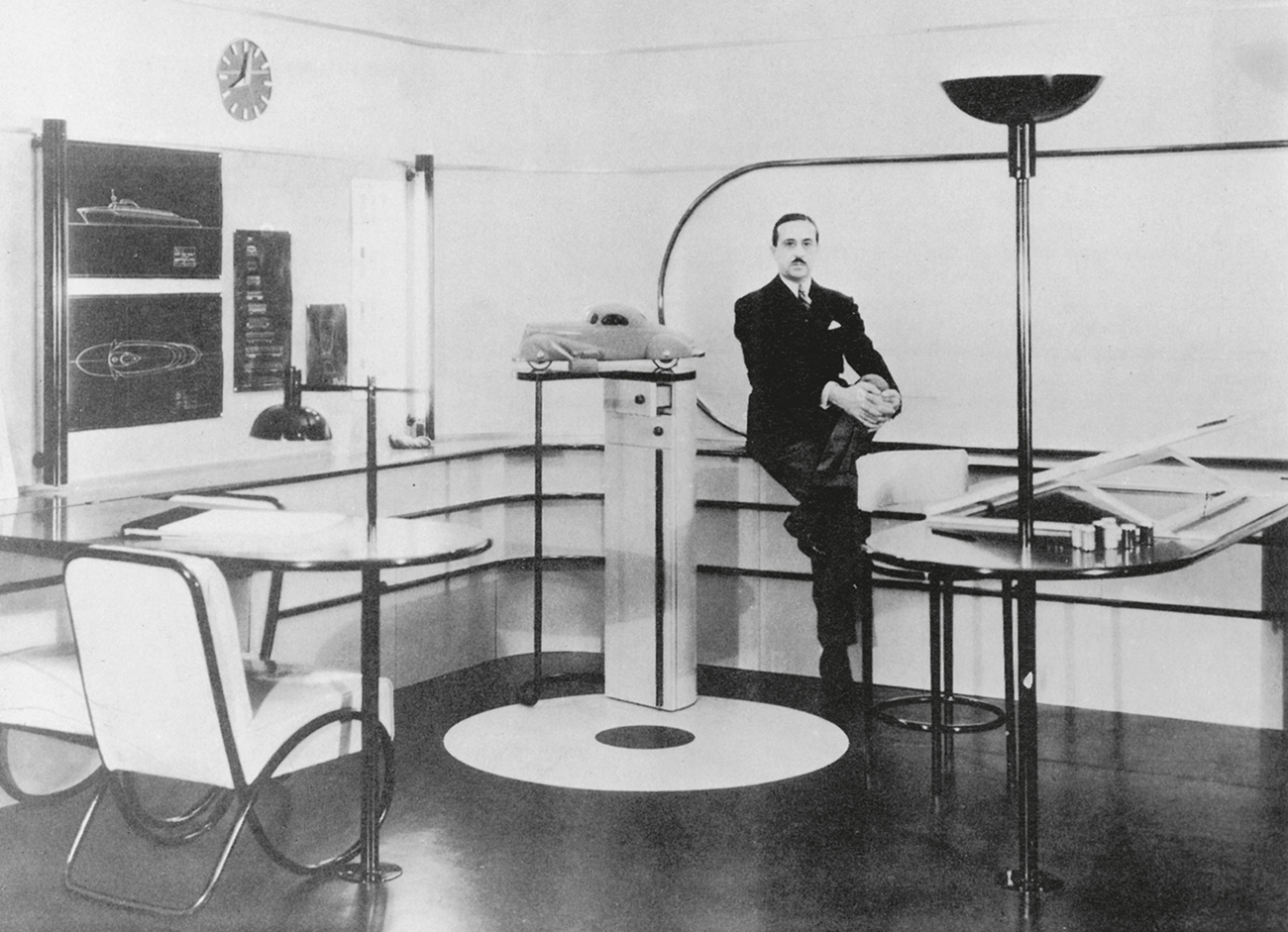

As a result of the 1929 Wall Street Crash American manufacturers found themselves compelled to stimulate new markets for their products. Design grew in importance as it was recognized as a marketing tool. Individual designers began to enjoy almost film-star status as manufacturers discovered that design sold goods. Norman Bel Geddes (1893–1958), Henry Dreyfuss (1904–1972) and Walter Dorwin Teague (1883–1960) were just three of the new breed of designers who established practices devoted to the design of everything from cameras and fridges to ocean liners and trains. Their concern for the total look of any design can be traced back to the example of the French ensemblier. Streamlining was the style in which such designers chose to work.

91 An industrial designer’s office, with its designer. Raymond Loewy in his mock-up for the ‘Contemporary American Industrial Art’ exhibition, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1934.

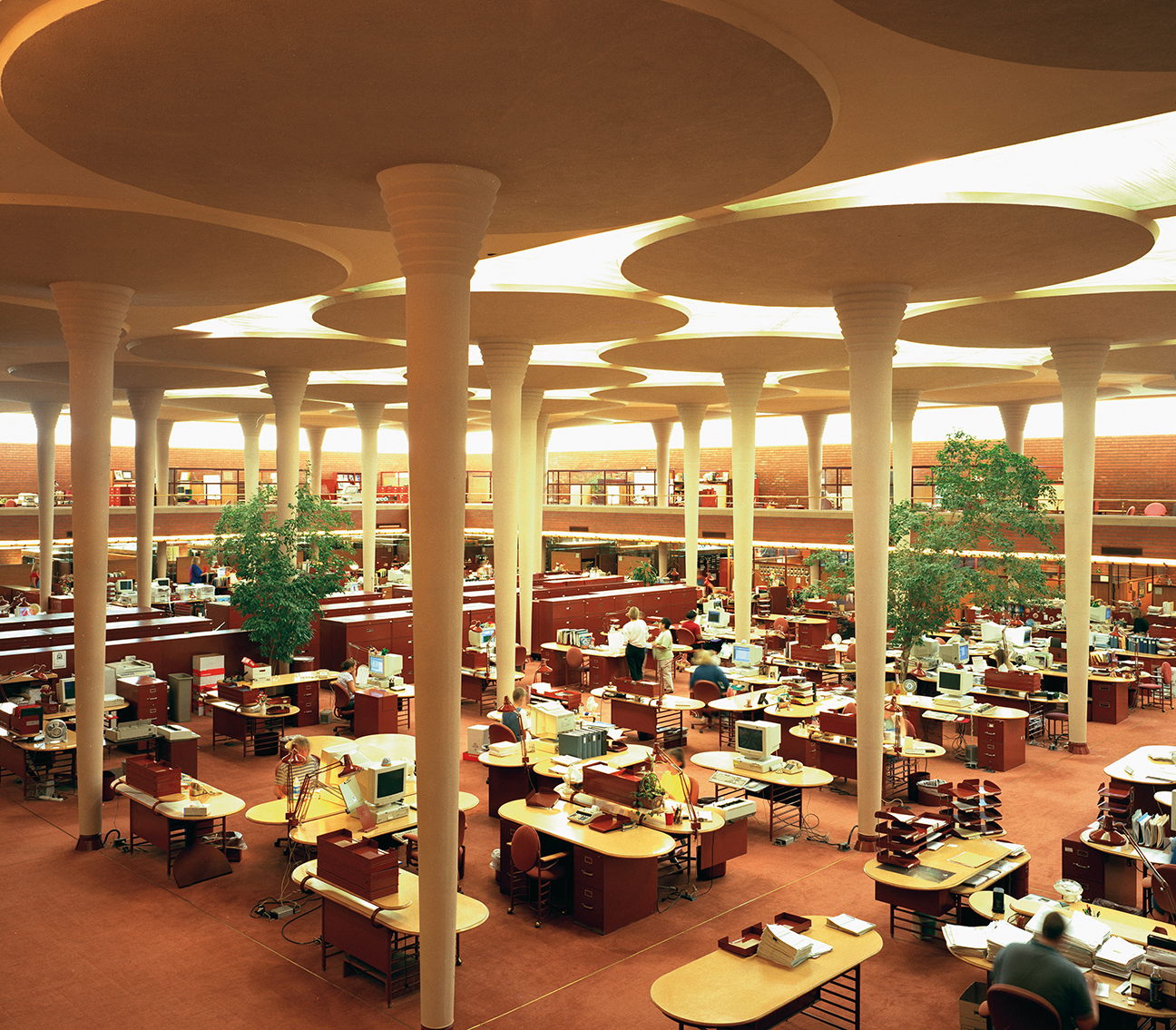

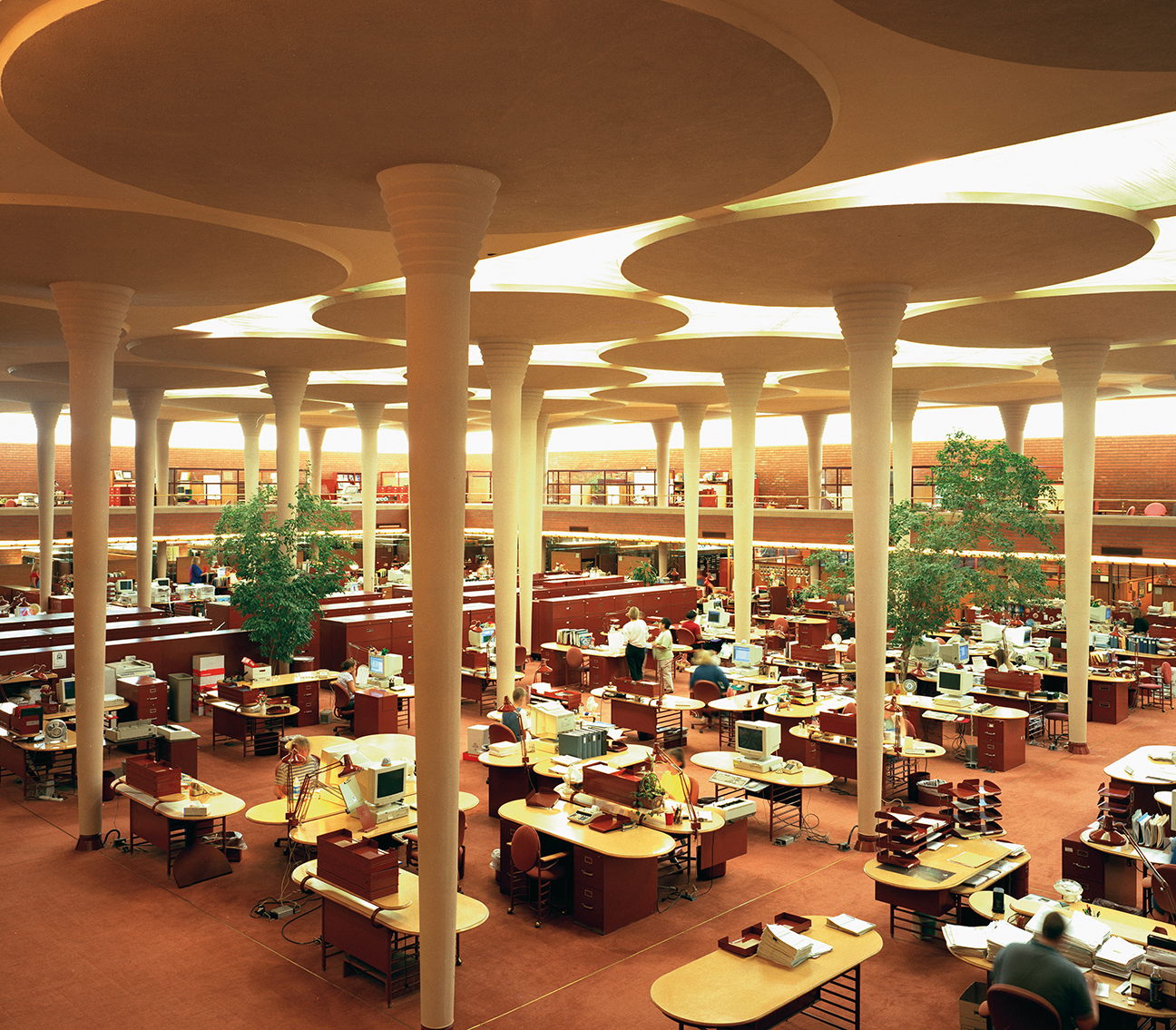

92 ‘Great Workroom’ of the Johnson Wax Building, Racine, Wisconsin, designed and furnished by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1936–9.

Adopting shapes developed in experiments with aerodynamics in cars and trains, the American moderne grew out of a need to express the new dynamism of American life. It combined the sleek surfaces of art deco, the French moderne preference for new materials, and an optimistic view of machinery inspired by the Italian futurist movement and America’s own Stuart Davis, who rendered the excitement of American mass culture in paint. In an America recovered from the severe blow of the Wall Street Crash, a new optimism and faith in the future prevailed. Less restricted by tradition than Europe, American society freely adopted streamlining for every domestic and public purpose. Because of its aerodynamic source and emphasis on the horizontal, interiors in the style often had three horizontal bands running round the walls. Also rooted in aerodynamics were the teardrop shape and smooth rounded corners.

Early examples can be seen in the new designs for trains. Beginning with the Union Pacific Railroad’s ‘City of Salina’ of 1934 (produced by the Pullman Car and Manufacturing Company) and culminating in Dreyfuss’s ‘20th Century Limited’ of 1938 for New York Central, the trains were styled with bullet-shaped fronts and horizontal banding to symbolize the airflow as the train sped along. For the interior, Dreyfuss used venetian blinds and horizontal bands at the top of columns and on the metal lampshades to carry the airstream motif through. New materials and finishes were also important to the style. In ‘20th Century Limited’ Dreyfuss gave a moderne look with coloured metallic finishes, cork panelling and plastic laminates.

Streamlining began as an appropriate style for transport, but was applied to all areas of design during the 1930s, from kitchen appliances like irons to office equipment. Raymond Loewy’s ‘Model Office and Studio for an Industrial Designer’, designed for the Metropolitan Museum’s 1934 exhibition ‘Contemporary American Industrial Art’, is made almost entirely from ivory-coloured plastic laminate and blue gunmetal.[91] Again, the horizontal is emphasized with three metal bands running round the room. All the lines are curved, including the window frames and furniture, to give the whole interior an effect of smoothness.

Frank Lloyd Wright used the same moderne style for his Johnson Wax Building, Racine, Wisconsin (1936–9).[92] The vast main office space is punctuated by support columns that are stepped outwards in ziggurat-shape as they approach the ceiling and meet a circular pad which separates the areas of overhead lighting. The metal furniture Wright designed for the office echoes the motif with circles and horizontal bands. The interior of New York City’s Radio City Music Hall (1933), largely by designer Donald Deskey (1894–1989), is a particularly fine example of the application of streamlining to a commercial interior.[93] Clean smooth lines, mirrors, chromium-plated steel and tubular aluminium furniture, veneers, Bakelite and lacquer are used to create an atmosphere of glamour and luxury.

The sleek surfaces of the moderne and streamlining were fully exploited by the American motion picture industry, for the moderne style matched the buoyantly confident mood of inter-war Hollywood. In the early days of cinema, sets were merely theatrical backdrops adapted for black-and-white presentation. By 1915 the profession of ‘art director’ had been created, reflecting the influence of European experimental art, architecture and theatre, particularly expressionism. Cedric Gibbons, one of the first art directors, described his role with modesty in 1938: ‘The audience should be aware of only one thing – that the settings harmonize with the atmosphere of the story and the type of character in it.’[95] Inspired by a visit to the 1925 Paris Exposition, in Grand Hotel (MGM, 1932) Gibbons created sumptuous interiors with satin bed covers and wall-hangings, moderne furniture and mirrors as the appropriate setting for the star of the film, Greta Garbo. But it was for the musical that the most lavish sets were created, Busby Berkeley’s Gold Diggers of 1933 (MGM, 1933) and films starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers – for example Top Hat (RKO, 1935) – made full use of reflective surfaces, long sweeping curves and ziggurat outlines. The impact of such mise en scènes on interior design at all levels was immense.

Cinema attendance in Britain reached a peak between the wars. Most adults visited the cinema at least once a week during the days of the Depression, when an evening of Hollywood films offered warmth and escapist glamour. The Hollywood cinema and the moderne style as a whole inspired a generation of British architect-designers to dispense with period detailing like picture rails, cornices and dados. Smooth, clean surfaces were emphasized with mirrors or reflective materials such as silver foil, paint or metal. When in 1930 the Australian architect-designer Raymond McGrath (1903–1977) refurbished a Victorian house in Cambridge, he renamed it ‘Finella’ after the Scottish queen who built a glass palace. The interior was entirely reflective. The entrance-hall floor was covered with black induroleum, the walls were silver-leaf sprayed with green lacquer, and the ceiling covered with green glass. The pilasters were green cast sheet-glass banded in chromium and lit from within. The architect Basil Ionides (1884–1950) designed the Savoy Theatre, London, in 1929 with an auditorium decorated in silver-leaf picked out in different shades of gold lacquer.

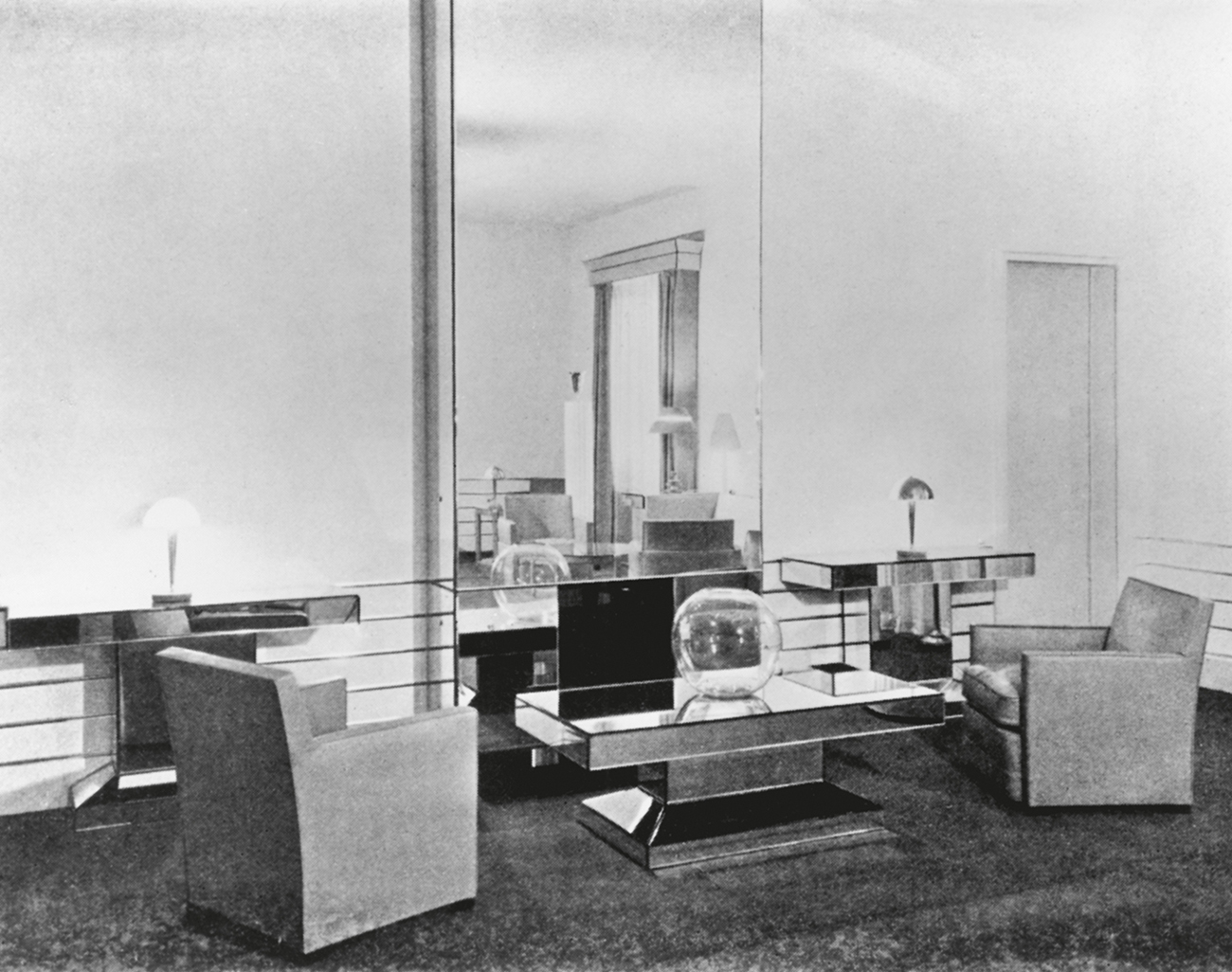

93 Donald Deskey: private apartment for the manager of Radio City Music Hall, New York City, 1933. An outstanding example of the American moderne, with exotic cherrywood panelling and furniture of lacquered and veneered wood, Bakelite and brushed aluminium.

94 Donald Deskey: dining room for Abbey Rockefeller Milton, Manhattan, 1933–4. ‘Silver glazed’ walls, Macassar ebony table and white leather for the chairs recall the French designers’ love of rich materials.

95 Hollywood movies spread the message of the American moderne: ‘Our Dancing Daughters’, 1928. Set designed by art director Cedric Gibbons, with French art deco pillowed divan and Hollywood-style stepped screen.

The architect-designer Oliver Hill (1887–1968), admired for his more historicist work in the 1920s, became a convinced moderne designer in the 1930s. He carried the reflective surface to its furthest extreme in designing an all-glass display for Pilkington Brothers (the major glass manufacturers) at the furniture exhibition at Dorland Hall, London, in 1933. The floor was made up of glass tiles with gold and mirrored mosaic, the walls were decorated glass panels, and the furniture was made of plate glass. Hill’s design of c. 1931 for the entrance hall of Gayfere House, London, for Lady Mount Temple, consisted of mirror-glass from ceiling to floor with a gleaming wooden floor and illuminated pillars.

Lighting became important in itself during the development of the inter-war interior. Chermayeff’s design for the Cambridge Theatre, London, and Oliver Percy Bernard’s (1881–1939) foyer of the Strand Palace Hotel, London, both of 1930, use lighting as an architectural element.[96] In the Cambridge Theatre coloured, geometrically patterned glass screens are used to conceal the light source. In the Strand Palace Hotel, columns and stairs seem composed entirely of strips of light. Such devices were used particularly for the design of new building types, most notably cinemas.

Some cinema interiors were based loosely on classical models, but the majority were moderne.[97] Trent and Lewis’s New Victoria Cinema in London of 1929 is typical, with fan-shaped columns dramatized by concealed lighting. The Odeon chain, designed mainly by H.W. Weedon (1887–1970) between 1934 and 1939, used art deco motifs to great effect, particularly shiny surfaces and Egyptian or Assyrian patterns, ziggurat outlines, bright-coloured squares or scrolls and geometric figures.

96 Oliver Percy Bernard: foyer entrance, Strand Palace Hotel, London, 1930. Lighting used as an architectural element.

97 New Victoria Cinema, London, designed by Trent and Lewis, 1929. Shell-capped sidelights suggest an underwater palace.

The cheapness of electricity had encouraged its use in interior design and also opened up a mass market for domestic consumer goods. A number of new factories were constructed on Western Avenue, one of the main routes out of London, for American clients by Thomas Wallis, Gilbert & Partners. The Hoover Factory (1932) is a symmetrical, classical-style building with bold moderne decoration. The main entrance is dominated by a coloured glass sunburst, symbol of energy and modernity, and the boardroom inside the building looks out through the top half of this imposing window. The style of the factory was an important ingredient of the corporate image, and in Britain as elsewhere, the use of the moderne denoted a progressive and successful company. The pure International Style’s message of ultra-modernity and democratic functionalism was understood by few at this period.

In Britain art deco and the moderne gained mass appeal in the later 1930s.[98] The four million homes built between 1919 and 1939 in England and Wales were typically modest-sized, semi-detached, and located in the suburbs. Tudor Revival is the most commonly used style, with half-timbering outside, and such motifs as galleons in stained glass in the panes of the windows. Combined with these are lively art deco motifs, particularly the rising sun, which figured on garden gates, in the window-glass and particularly on radio cabinets. The three-piece suite was a new feature of the middle-class lounge; it consisted of a two- or three-seater couch and two armchairs, thickly upholstered to suggest comfort, and covered with leather, velveteen or moquette, which might be decorated with moderne geometric designs. The glazed china cabinet was often used to display the best tea service. The ‘Crocus’ design tea-set by Clarice Cliff (1899–1972), for example, consisted of angular-shaped pieces, cream coloured and decorated with vivid triangular patterns in bright orange and black.

Art deco and the moderne had an equally pervasive influence on the American domestic interior during the inter-war years, until by the end of the 1930s America enjoyed a confidence in the creation of a style that owed little to European models. Paul T. Frankl, a Viennese-born designer who had emigrated to America, proclaimed in New Dimensions (1928) that ‘new ground has been broken and the foundation for a distinctive American art is already being laid’. He celebrated this belief in his own designs for ‘Skyscraper Furniture’, inspired by the building-type that American architects had invented and developed independently of Europe.[99] In a more conservative vein, Americans were also responsible for founding and nurturing the profession devoted to the overall look of a room, that of interior decorator.

98 Popular art deco: a suburban lounge. Wooden fittings from a house of c. 1937 with the authentic furniture (Geffrye Museum, London).

99 Paul T. Frankl: sitting room, displayed at Abram & Strauss, New York, 1929. A ‘Skyscraper’ bookcase mirrors the burgeoning Manhattan skyline.