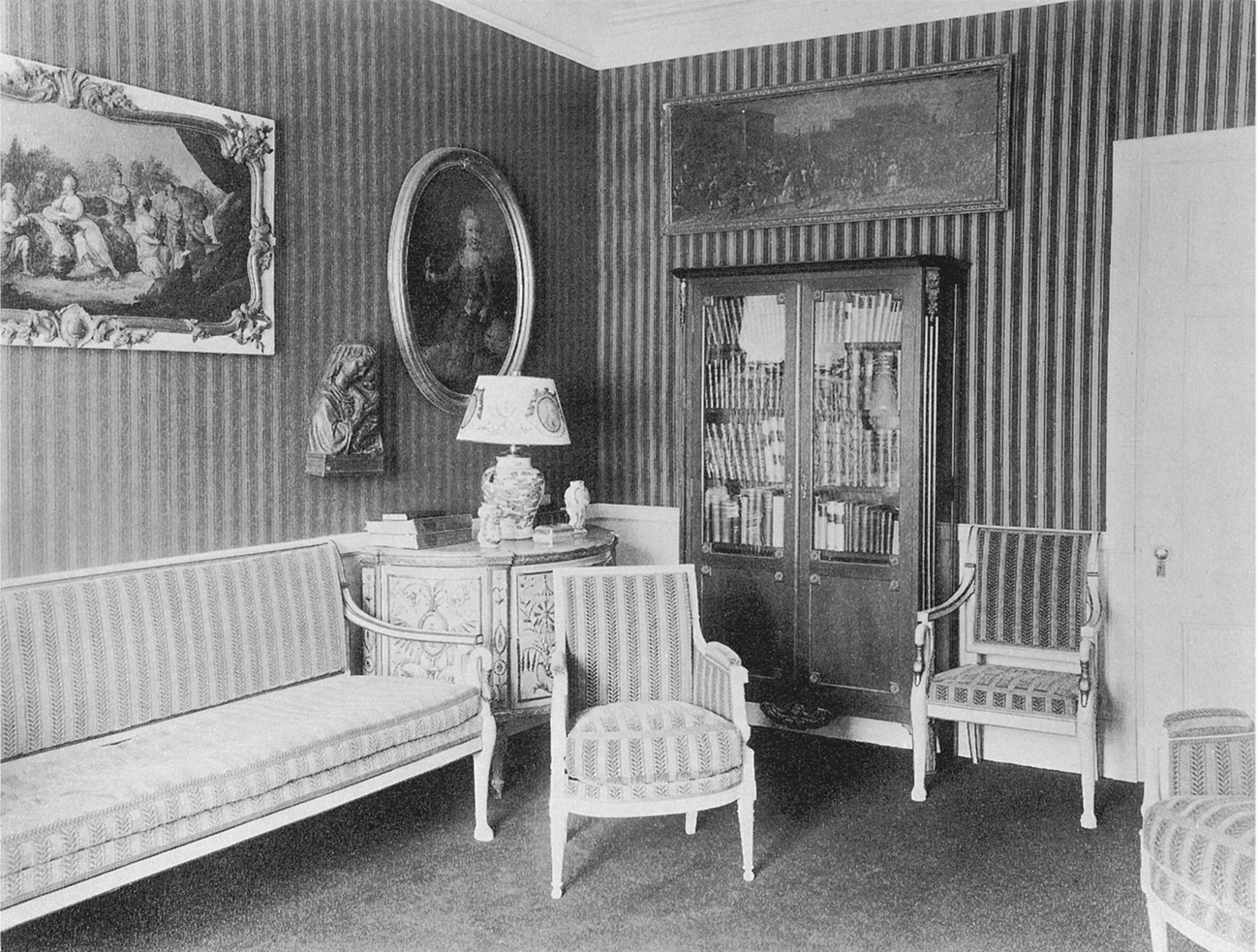

100 The ‘Old French look’. Ogden Codman Jr: parlour for the future novelist Edith Wharton, New York, c. 1903.

Before the twentieth century the profession of ‘interior decoration’ simply did not exist. Traditionally it was the upholsterer, cabinetmaker or retailer who advised on the arrangement of interiors. In London, the firm of Lenygon and Morant, founded in 1915, was typical. Francis Lenygon was primarily a furniture dealer, supplying chiefly Americans through the art dealer Joseph Duveen. His decorating work was a marginal part of the business he shared with Morant, the traditional upholsterer. Their London showroom was situated in a Palladian house, and was used to display English antique furniture from the sixteenth to mid-eighteenth centuries, when, it was generally considered, the production of ‘good’ furniture came to an end. Twentieth-century interior decorators consistently worked within the styles of the past, and until the First World War decorating was almost synonymous with the antique trade.

The rise of the interior decorator during the twentieth century was the result of changed social and economic circumstances. The employment of an interior decorator was, and remains, an expensive luxury, available only to the upper echelons of society. There is a certain status attached to using a professional to advise on the appearance of your home or workplace. During the early years of the century American millionaires sought to express power and prestige by using professional decorators to recreate Renaissance palaces or French châteaux. In the 1920s and 1930s, the heyday of the decorator, there was a greater emphasis than ever before on entertaining, and decorators were employed to create suitable backdrops for the lavish cocktail parties then fashionable. Their services remained in demand during the Depression because it was cheaper to redecorate an existing house than build a new one.

The role of interior decorator has always been one of adviser and even confidante. Because of the consultative nature of the work it has been one of the few professions in which women have led and excelled. In the years preceding the First World War interior decoration emerged as an acceptable new profession for women.

Inspired by the suffragette movement in America, women strove to establish economic independence from husbands or fathers, and one of the means open to them was the orchestration of the overall appearance of pre-existing rooms. This role has changed little since the 1900s. Decorators are chiefly responsible for selecting suitable textiles, floor- and wall-coverings, furniture, lighting and an overall colour scheme for rooms that may already contain some of these elements. The interior decorator is rarely responsible for structural alterations, which are the preserve of the architect.

Interior decoration never enjoyed the status of architecture or even interior design, being regarded as a branch of fashion. This could be explained by its ephemeral nature, for few schemes remain intact for any length of time. The lack of seriousness associated with interior decoration could also be explained by the dominance of women in the profession’s early days. The Victorian middle-class woman was expected to stay at home and manage the household and servants. The decoration of the domestic interior was a respectable pastime that allowed women some control over their environment. Periodicals such as Home Chat (1895–1968), as well as various home manuals, advised on the selection of furniture and furnishings and the application of decorating techniques such as stencilling. As Jacob von Falke, vice-director of the Austrian Museum of Art and Industry, described the position in the popular American edition of Art in the House (1879): ‘taste in woman may be said to be natural to her sex. She is the mistress of the house in which she orders like a queen.’

The extension of the traditional female role into professional practice began in America, where women were less restricted by established codes of behaviour. Candace Wheeler (1827–1923) was an American textile designer who did much to further the cause of women’s professional employment when in 1877 she established the New York Society of Decorative Art to educate women and find outlets for their handicrafts. As Wheeler commented, the new Society ‘opened the door to honest effort among women’, and, ‘if it was narrow, it was still a door … the idea of earning had entered into the minds of women’. In 1879 Wheeler went on to establish L.C. Tiffany and Associated Artists with Louis Comfort Tiffany, the son of the founder of Tiffany and Co., and in 1883 she formed a breakaway company run entirely by women, Associated Artists, which became one of the most successful decorating firms in America, designing interiors, wallpaper, fabrics and embroidery in a style inspired by the British arts and crafts and aesthetic movements. She shared the secret of her success in the book Principles of Home Decoration With Practical Examples (1903), and publicized her encouragement of professionals in an article entitled ‘Interior Decoration as a Profession for Women’ in The Outlook magazine in 1895. This marked the beginning of the social acceptability of such a career for women.

Interior decoration gained status with the publication in 1897 of The Decoration of Houses by the future novelist Edith Wharton and architect Ogden Codman. The book set a precedent for all subsequent decorating activity by equating ‘natural good taste’ with English, Italian and French models from the Renaissance onwards. There was particular emphasis in the book on French eighteenth-century interiors which was to inspire a lasting admiration among decorators and their clients for the ‘Old French look’. The comparative simplicity of Louis XV, Louis XVI and Directoire furniture was preferred to the overblown revivalism of the later nineteenth century. The parlour designed by Ogden Codman for Wharton at 884 Park Avenue, New York City, had a marked freshness and simplicity, achieved with austere striped wallpaper and upholstery and painted Directoire furniture.[100] Wharton and Codman identified the principles of proportion and harmony as the most significant for the planning of interior schemes. Taken from classical architecture, such laws have had an enduring appeal for the decorator. During the late nineteenth century classicism had been identified as the most appropriate style to symbolize the American Republic. It evoked qualities of solidity, endurance and universal harmony.

100 The ‘Old French look’. Ogden Codman Jr: parlour for the future novelist Edith Wharton, New York, c. 1903.

The craft of the interior decorator became associated with the elegant, if not entirely accurate, recreation of antique interiors. Such historicism was inextricably bound up with the notion of ‘good taste’, which the decorator possessed by virtue of studying the decorative styles of the past and being a member of the same social circles as his or her patrons. The criterion of ‘good taste’ was to dominate the profession throughout the twentieth century, with decorators rarely designing wholly modern interiors. The House Beautiful magazine included a long-running series entitled ‘The House in Good Taste’, and numerous books appeared on the subject, including Furnishing the Home in Good Taste (1912) by Lucy Abbot Throop, Good Taste in Home Decoration (1954) by Donald D. MacMillen, and in 1968 a contribution by Britain’s leading decorator, David Hicks: On Living – With Taste.

Elsie de Wolfe (1865–1950), a pioneer of the profession of interior decoration in America, contributed to the trend in 1913 with her book The House in Good Taste, which included the advice that ‘It is the personality of the mistress that the home expresses. Men are forever guests in our homes, no matter how much happiness they may find there.’ De Wolfe began her professional life as an actress, attracting attention less by her performances than her dress sense, bringing the latest Parisian creations of Paquin and the House of Worth to New York. By her own efforts she gained an entrée to New York high society, at that time dominated by the Vanderbilts.

Her earliest foray in 1897–8 was the decoration of the house she shared with wealthy theatrical agent Elisabeth Marbury in Irving Place, New York City.[101-2] She was inspired to bring ‘light, air and comfort’ to the dark, cramped Victorian interior by the writing of Wharton and Codman. During the last two decades of the nineteenth century there had been a general move among the upper classes towards a greater restraint in interior decoration, as the trappings of the resplendent mid-nineteenth-century parlour became available to their social inferiors through mass production and a higher standard of living. The American breakfast-cereal magnate Dr John Harvey Kellogg had contributed to the trend when he inspired a whole health-reform movement with his writings, which castigated fashionable excesses as unhealthy.

101–2 Elsie de Wolfe’s dining room at Irving Place, New York City, before redecoration in 1896, and transformed in 1898.

De Wolfe revitalized the interior by stripping away the Victorian features. She removed the gasolier, decorative plates, oil painting, rococo mirror, and the jumble of oriental carpets. After redecoration the room was lit by sconces mounted against simple white-framed mirrors. She placed a plainer mirror and classical French bust over the mantelpiece. The floor was covered with a single unpatterned carpet. The room was made considerably lighter by painting the woodwork pale grey, and substituting more elegant painted chairs of Louis XVI type. The rest of the house was treated in the same way. A constant stream of high society, literary and artistic visitors was impressed by her transformation of what had been a mediocre interior.

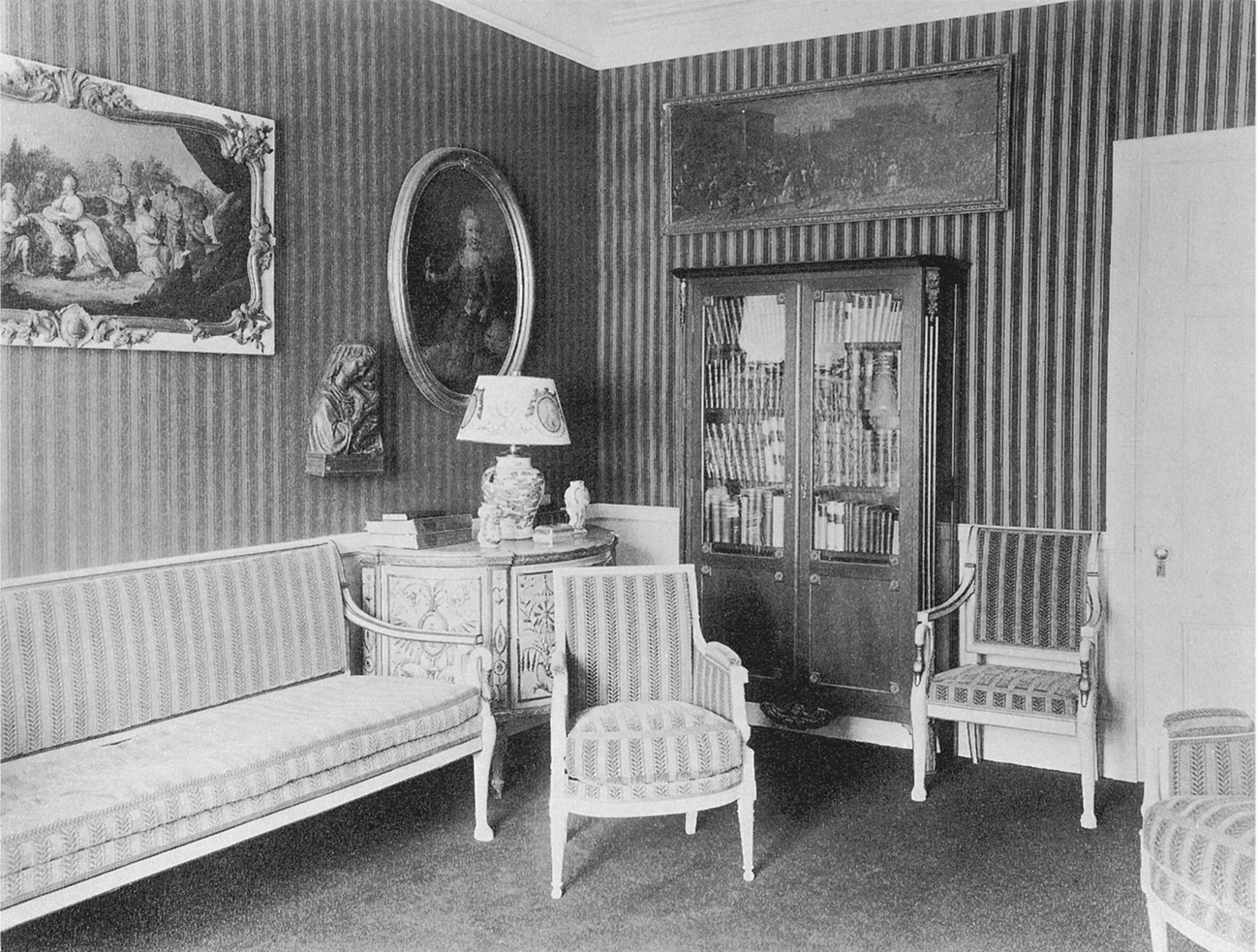

103 Elsie de Wolfe: Trellis Room, Colony Club, New York City, begun 1905. From The House in Good Taste, 1913. French inspiration for the trellised ‘country look’

The leading New York Beaux-Arts architect, Stanford White, admired De Wolfe’s achievements, and in 1905 secured for her the contract for the interior decoration of his building for New York City’s Colony Club, a new club open only to women members.[103] This was the first public interior to be designed by a professional interior decorator, rather than by an architect or antique dealer. De Wolfe was inspired by the elegant rooms she had seen in English country houses in the 1880s. She visited both England and France to acquire suitable antique furniture and samples of the chintzes that were to become her trademark. The bedrooms, private dining room and library all had the same refined look. The walls were painted in pale tones, the furniture was mainly slender and light, and the large prints of the chintzes added an English country atmosphere. In the tea room the green-painted trellis work, tiled floor and wicker furniture evoked a conservatory rather than a city-centre club.

De Wolfe’s scheme was a success and guaranteed her further commissions. The most prestigious of these came from the millionaire Henry Clay Frick. On a visit to Hertford House, the former London residence of Sir Richard Wallace (now the Wallace Collection), Frick had been impressed by the display of eighteenth-century French fine and decorative art, recently bequeathed to the nation. Determined to found a similar institution in America, Frick commissioned the architects Carrère and Hastings to design a Renaissance palace on Fifth Avenue, New York City, to house an extensive collection of eighteenth-century French art which he formed with the advice of the English picture- and antique-dealer Edward Duveen. Duveen’s English decorator William Allom was responsible for the public area on the ground floor. Frick commissioned De Wolfe to decorate the upper floor, used only by his close family. She worked for a ten per cent commission of costs, and it appears that these totalled over one million dollars. Most of De Wolfe’s purchases were made in Paris from Lady Victoria Sackville-West, who had inherited a premier collection of French antiques, assembled by Wallace, from her lifelong friend, the connoisseur Sir John Murray Scott. The Frick commission made De Wolfe’s name, and she went on to decorate numerous interiors for America’s wealthy families.

Elsie de Wolfe established the working pattern for subsequent interior decorators. Her trips to Europe to gather antique furniture and fabrics, the extensive social contacts with potential clients, her adherence to the Wharton and Codman approach and taste for the ‘Old French’, set a standard. A group of professional decorators emerged during the 1920s and 1930s in America and England, eager to emulate her success. Nancy McClelland (1876–1959) established the decorating section for Wanamakers department store, New York, in 1913, the first of its type in America, and in 1922 went on to establish a decorating firm that specialized in the accurate recreation of period interiors for the domestic market and museums. Eleanor McMillen (1890–1991, known as Eleanor McMillen Brown from 1935) worked within the same classical idiom, and founded McMillen Inc. in 1924 as ‘the first professional full-service interior decorating firm in America’. She had taken courses in art history and business practice, and was determined not to be identified with the rather amateurish approach of her contemporaries. The firm survives into the twenty-first century, with characteristic interiors using acid yellow to offset symmetrically placed antique furniture. In a commission for Mrs Millicent Rogers in New York, McMillen brought the classic decorator’s features of black-and-white checked floor, trompe l’oeil details on the walls and symmetrically placed antique furniture to the hall, where a European, late nineteenth-century sofa upholstered in satin looks ill at ease.[104-5] Wealthy Americans lacked confidence in their own cultural heritage, and generally looked to European models.

Ruby Ross Wood (1881–1950) was an admirer of De Wolfe who began her professional life as a journalist, ghost-writing De Wolfe’s Ladies’ Home Journal articles which became The House in Good Taste. Wood established herself as an interior decorator with the publication of her own book, The Honest House (1914), which illustrated the interiors of her Forest Hills Gardens home at Long Island. She was inspired by eighteenth-century English and American Colonial models, rather than the sophisticated French antiques favoured by De Wolfe and others. This trend had been encouraged by the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition and the Chicago Columbian Exhibition of 1893, and gained further momentum from the opening of the American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in October 1924 with its sixteen period rooms.

After running Au Quatrième for Wanamakers, Wood established her own decorating firm in the 1920s. Her design for Swan House, Atlanta, Georgia (1928), for Mrs Emily Inman combined the restraint of fine antiques with the homeliness of the Colonial style. In the dining room she juxtaposed a bold check curtain with an eighteenth-century hand-painted wallpaper. The room was furnished with a rococo mirror, console tables and antique tea-caddies to recreate an eighteenth-century Colonial interior. Frances Ad;er Elkins (1888–1953), the sister of Beaux-Arts architect David Adler, was another decorator who mixed American traditional styles with French and English antiques. Her own adobe house, Casa Amesti, in Monterey, California (1918), successfully combined European antiques with traditional Spanish Colonial features such as rough plasterwork, bare floorboards and exposed ceilings. The house attracted widespread admiration, and she designed domestic interiors throughout Chicago and California in the same mode.

104–5 Eleanor McMillen (Brown): hall and sitting room for Mrs Millicent Rogers, New York, late 1920s. The wall treatment of hanging textiles was inspired by the French Empire style, which in turn was taken from Roman sources.

Women also played an important role in founding the profession of interior decoration in Britain.[106] Betty Joel (1896–1985) established her own furniture-making and interior decoration business after the First World War, eventually opening a showroom in Knightsbridge with twelve room settings. She was inspired by art deco to create bold designs such as ziggurat-shaped bookcases and curved sofas. Her interiors reflected the geometrical inspiration of art deco mingled with the smoothness and glamour of the moderne, as in the all-silver bedroom at Elveden Hall, Suffolk. The firm undertook a wide variety of commercial decorating work for shops, hotels and boardrooms. In contrast, the two women who contributed most towards the establishment of interior decoration in Britain, Syrie Maugham (1879–1955) and Lady Sybil Colefax (1875–1950), worked largely on private commissions.

106 Betty Joel: characteristically unconventional moderne chaise longue, and her patterned rug. From Derek Patmore, Colour Schemes for the Modern Home, London, 1933.

Syrie Maugham was the wife first of Henry Wellcome, the founder of the pharmaceutical firm, and then of the novelist Somerset Maugham. After the end of her second marriage she learned the basics of the trade by working under Ernest Thornton Smith, head of Fortnum and Mason’s antique department, and went on to become the most fashionable interior decorator in London.

Like Elsie de Wolfe, with whom she had visited India, Maugham created elegant interiors using eighteenth-century French furniture with elements of the moderne and light colours. She created the fashion for ‘pickling’ furniture – that is, stripping antique chairs and tables of their original dark polish and finishing them with light paint or wax. Her distinctive style is best exemplified by the influential ‘All-White’ interior she created for her London house in c. 1929–30.[107] The dining room had stripped-pine panelling and a floor-length ivory tablecloth. Tones of white and cream were used for the drawing-room upholstery, curtains, and an abstract rug commissioned from Marion Dorn. Three Louis XV chairs were painted off-white, and a moderne touch was added with a chromium-and-mirror screen. Maugham produced all-white rooms for her clients, including a bedroom for Mrs Tobin Clark at a house designed by David Adler in San Mateo, California (1930). Her commissions included interiors for Noël Coward, Mrs Wallis Simpson and the Prince of Wales.

107 Syrie Maugham: ‘All-White’ drawing room for her own house, London, c. 1929–30. The society decorator’s most famous project. The low sofa covered in beige silk, low table, screens, and especially ‘white on white’ decor were to be strongly influential.

108 Syrie Maugham: interior at Wilsford Manor, near Amesbury, Wiltshire, mid-1930s. Design for the country house of the artist, poet and aesthete the Hon. Stephen Tennant.

109 Rex Whistler: ‘Painted Room’, Port Lympne, Kent, 1930–2. Brilliant trompe l’œil paintwork simulates striped fabric, with the witty addition of genuine tassels. The furniture was chiefly designed by the architect of the house, Philip Tilden.

Maugham created idiosyncratic interiors, mixing the Parisian moderne with the antique. Her rival Lady Sybil Colefax created very English interiors, inspired by the chintz and solid furniture of the English country house. She had turned from life as a London hostess to become a professional decorator in 1933, after losing money in the Wall Street Crash. In 1938 she took on a partner, John Fowler (1906–1977), an expert on eighteenth-century decoration and one of the most influential figures for the period decoration of houses.

The historical inspiration for decor was prevalent in Britain in the 1930s. An increased awareness of the value of the British heritage had been inspired in part by scholarly activity in the area of historic buildings, and public interest was heightened by magazines such as Country Life (founded 1897), and by the National Trust. Many of the clients who commissioned work from interior decorators themselves lived in historic buildings, and wished to maintain or recreate the authentic interiors. Fowler fulfilled their requirements with his expert advice on curtaining, paint colours, finishes, floor coverings and furniture. During the post-war years Fowler was responsible for the restoration of a number of significant British interiors, including 44 Berkeley Square, designed by William Kent, the Adam interiors of Syon House, Middlesex, and James Wyatt’s Cloisters at Wilton House, Wiltshire. Such schemes and his work on properties for the National Trust needed to be historically accurate, but the smaller-scale interiors he decorated bear his individual stamp. The sitting room for the Countess of Haddington at Tyninghame in Lothian, Scotland, is characteristic with rich curtaining, chintz, heavy fringing, pyramid-shaped bookcases and chandelier. Rooms such as this were featured in British and foreign periodicals throughout Fowler’s career, and contributed markedly to the popularity of the English country house look from the 1930s onwards. The British mural-painter Rex Whistler (1905–1944) worked in a number of English country houses during the inter-war years, as well as the Tate Gallery Restaurant in London, where he painted The Expedition in Pursuit of Rare Meats (1924–5), and his recreations of eighteenth-century scenes charmed English society.[109] In the dining room at Plas Newydd for Lord Anglesey (1936–8) he used trompe l’oeil techniques on the ceiling and end walls, and painted a romanticized classical harbour scene on the long wall facing the windows.

110 Emilio Terry with Charles de Beistigui: roof terrace of the Beistigui apartment, Paris, 1930.

While some British decorators were excelling in recreating the past, others in Britain, France and America were finding novel sources of inspiration, such as surrealism, for the creation of witty rooms. The surrealist movement began in 1924 with the publication of the Manifesto du Surréalisme in Paris. Surrealist painters including René Magritte and Salvador Dalí attempted to illustrate the threatening world of the subconscious in their paintings, most often by juxtaposing incongruous elements within the picture frame to startle the viewer and undermine everyday expectations. The surrealist influence first came to the fore in Paris, where surrealism had been conceived. The Mexican millionaire collector Charles de Beistigui had commissioned an apartment from Le Corbusier in 1931 and by the time it was completed, and de Beistigui came to decorate the interior, he had developed an interest in the style.[110] In collaboration with architect-decorator Emilio Terry he created a surreal interior with out-of-scale furniture.

Ornate Second Empire gold-and-white chairs in the Cinema Room overpower the simple lines of Le Corbusier’s spiral staircase, and on the roof terrace, artificial grass formed the carpet for baroque garden furniture. The walls were painted blue, and a mirror set above the fireplace reflected views of the Champs Elysées.

In the 1930s the influence of surrealism also affected France’s leading interior decorator, Jean-Michel Frank (1895–1941), renowned for his supremely simple but expensively elegant interiors. He had influenced and supplied leading American decorators, including Elsie de Wolfe, Frances Adler Elkins and Eleanor Brown, with art deco emphasis on the quality and rarity of the materials used.[111] The Cinema Ballroom he designed for Baron Roland de l’Espée (1936) was a major departure. The colour scheme was startling: there was a bright red carpet and one pink, one pale blue, one sea-green and one yellow wall. The theatre boxes hung with purple velvet flanked the ultimate in surrealist seating, the ‘Mae West Lips’ sofa (c. 1936) designed by Dalí and based on his painting, Mae West (1934, Art Institute of Chicago), which had depicted the film star’s lips as a sofa, her nose as a fireplace and her eyes as framed oil paintings. The British versions were commissioned in deep and pale pink felt by the great collector of surrealist art, Edward James, for Monkton House near Chichester, the country home he furnished and decorated as a monument to surrealism. A series of strange room settings used quilting on the walls, and a stair carpet was specially woven to reproduce James’s dog’s pawprints.

Edward James also commissioned the painter Paul Nash (1889–1946) to design a bathroom for his wife, the Viennese dancer Tilly Losch, at his London house. Like many artists during the Depression, Nash was forced to take on design work in order to make a living. He wrote passionately on the subject of design in his Room and Book (1932), decrying the British taste for historical revivals: ‘It is time we woke up and took an interest in our times. Just as the modern Italian has revolted against the idea that his country is nothing but a museum, so we should be ashamed to be regarded by the Americans as a charming old-world village.’[112] In Tilly Losch’s bathroom he provided a sleek interior with modern reflective materials. The walls were stippled glass, coated with an alloy to give a purple sheen, set off by peach-tinted mirrors. The fittings were all black, and the floor was covered in pink rubber. The fluorescent light on the wall was shaped as two half-moons, and the fitted electric fire was unusual enough at this time to be made a feature of the moderne interior. The moon was a recurring motif in Nash’s paintings, and the chromed barre was inspired by the metaphysical cover he designed for the book Dark Weeping (1929).

111 Jean-Michel Frank: Cinema Ballroom for Baron Roland de l’Espée, Paris, 1936, with the ‘Mae West’s Lips’ sofa designed by Salvador Dalí.

112 Paul Nash: all-glass bathroom for Tilly Losch, London, 1932. A painter’s sleek interior with stippled and plain mirror-glass.

American interior decorators were similarly influenced by the surrealist movement.[113] Dorothy Draper (1889–1969) displayed her debt to surrealism in the dramatic use of scale and striking manipulation of expectations of inside/outside. At the Arrowhead Springs Hotel in Southern California (1935) she installed overscaled furniture and neo-baroque white plaster decorations, while at the Hampshire House Hotel, Central Park South, New York (1937), she designed the function rooms as an outdoor space, complete with garden furniture and the exterior of a Georgian house to unnerve the visitor. The flamboyant Rose Cumming (1887–1968) found the ‘Old French taste’ of women like McClelland or McMillen Brown stale, and combined raw silk, satin, metallic wallpaper and silver furniture in fantasy interiors inspired by surrealism and Hollywood cinema.[114]

Cumming was of the same generation as de Wolfe, Ruby Ross Wood and Dorothy Draper. These women had pioneered the profession of interior decoration but were untrained; and brought with them an air of the dilettante. By the 1930s the whole profession had become more formalized. The American Institute of Interior Decorators (now the American Society of Interior Designers) was established in 1931, and trade magazines were founded in America including Home Furnishing from 1929 and The Decorators’ Digest in 1932 (renamed Interior Design in the 1950s). A new generation entered the profession in the 1930s with more formal training in design and a more business-like approach. Terence Harold Robsjohn-Gibbings (1905–1976), for instance, had an architectural training. He was brought to America by Charles Duveen, the antique dealer and brother of art dealer Joseph Duveen, and set up his own practice on Madison Avenue, New York City, in 1936. His designs were inspired by Ancient Greece and the moderne. The Klismos Chair and his mosaic-floored showroom (1936) display his eclectic knowledge of ancient and modern sources. His subsequent work for the California jeweller, Paul Flato, and his furniture designs indicate a debt to Swedish modernism. Less stark, with its extensive use of blond woods and other natural materials, Swedish modern was regarded as acceptable by the decorating world when the international modern was not. William Pahlmann (1900–1987) trained at the New York School of Fine and Applied Arts, and designed room settings for the New York department store Lord and Taylor from 1936. He promoted a variety of styles, including the moderne, as well as creating baroque settings worthy of the film Gone With the Wind.

113 Dorothy Draper: room for the Quitandinha Hotel, Petropolis, near Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1946. Sweeping curves and oversized candelabra owe a debt to the baroque and surrealism.

114 Rose Cumming: bedroom, the decorator’s own apartment, New York, 1946. A luminous grand design of shimmering greys, mixing fine period furniture with oriental and fantasy elements.

The rise in status of the interior decorator was halted for a time after the Second World War by shortages, and then aided by the emergence of the new profession of ‘interior designer’. Entrants to the profession would now usually be trained, relying less on ‘natural good taste’ and more on graduate education. Such designers increasingly worked on non-domestic commissions, as the commercial sector realized the value of good interior design.

In the grand milieu, John Fowler was succeeded as principal adviser to the National Trust in Britain in 1969 by David Mlinaric, who did not aim for the faded elegance of Fowler, but recreated period interiors with new textiles and gilding. Mlinaric’s private commissions reveal an eclectic use of antiques from different centuries. Another new figure on the post-war decorating scene, Michael Inchbald (1920–2013), showed the same disregard for historical accuracy, and incorporated a varied mixture of past styles in his interiors. He designed the luxury interior of the Queen Elizabeth 2 ocean liner, and his own London home provided a slightly quirky setting for an important collection of antique furniture and objets d’art. Perhaps the best known of all British interior decorators and designers, David Hicks (1929–1998), was an admirer of Inchbald’s work, and he showed the same skill in combining antiques with modern design.[116]

Hicks’s career was launched in 1954 when the decoration of the interior of his mother’s house in London was published in House and Garden. The combination of strong colours such as scarlet, black and cerulean blue in the library, the emphasis on crisp outline, and the careful table-top arrangements or ‘tablescapes’, all characterize Hick’s work. After a four-year partnership with Tom Parr, who went on to run Colefax & Fowler, he established his own business, David Hicks Ltd, in 1959. During the 1960s he contributed to the renaissance in British culture at a time when British pop groups, fashion designers, photographers and models dominated the international scene. His photograph appeared in David Bailey’s Box of Pin-Ups in 1965 as one of the young fashion leaders working in London.

115 David Hicks: drawing room, Eaton Place, London, 1954. Bold combinations of strong colours used for the project that launched Hicks’s career.

116 David Hicks: an artful division of bathroom and dressing-room, late 1960s. Note the geometric patterned rug.

117 Billy Baldwin: dining room of apartment of Placido Arango in Madrid. A characteristic blend of old and new, including an El Greco original and Louis XVI gilt chairs; pale yellow walls and white curtains complement a geometrically patterned rug.

The bathroom he designed for his wife in their house in the South of France in the late 1960s is characteristic of his style, with white-painted furniture, louvred shutters and a bold black-and-white patterned rug. The curtained bath ingeniously divides the bathroom from the dressing room. For his own Palladian Revival villa in Portugal in the 1980s, Hicks acted as architect, designer and decorator.

Hicks’s work, particularly his bold, geometric carpet and fabric designs, was influential in the United States. The leading post-war American interior decorator, Billy Baldwin (1903–1983), wrote that Hicks had ‘revolutionized the floors of the world with his small-patterned and striped carpeting’.[117] Baldwin also excelled in blending antiques into modern interiors: the ‘Old French’ style and Colonial Revival both remained popular with American decorators. Baldwin had begun his career working for Ruby Ross Wood in 1935, collaborating on the surrealist interior for a house in Montego Bay, Jamaica, in 1938. After Wood died in 1950 he went into partnership with designer Edward Martin in 1952. His debt to Wood is clear in his use of antiques in simple settings of plain white walls, bare floorboards and rush matting. Inspired by the brilliantly coloured paintings of Henri Matisse, he introduced exotic fabric prints and vivid mixtures of colours into his interiors during the 1950s. In the 1960s he became the most sought-after decorator in the USA, designing interiors for prominent figures such as the Paul Mellons and American Vogue editor and doyenne of fashion Diana Vreeland. His memoirs, Billy Baldwin, An Autobiography (1985), acknowledge his debt to the female pioneers of decorating, particularly Ruby Ross Wood.

Michael Taylor (1927–1986), who had a successful practice in San Francisco from 1957, was influenced by Syrie Maugham, acquiring most of Elkins’s business estate when she died, including designs brought from Maugham. Albert Hadley (1920–2012) was an admirer of Eleanor Brown, and in 1956 joined McMillen Inc. as a decorator. He used lighting designed by De Wolfe in his own apartment in the late 1950s. In 1962 Hadley went into partnership with Mrs Henry Parish II, another woman decorator of the early generation who was then working on the refurbishment of the White House, Washington, DC, for President and Mrs Kennedy. The new interiors reflected the eighteenth-century classical origins of the building, and expressed Mrs Kennedy’s interest in high culture. The firm of Parish-Hadley completed many historically based interiors during the 1970s. Post-war interior decorators have found lasting inspiration in the working practices of the women who founded the profession.