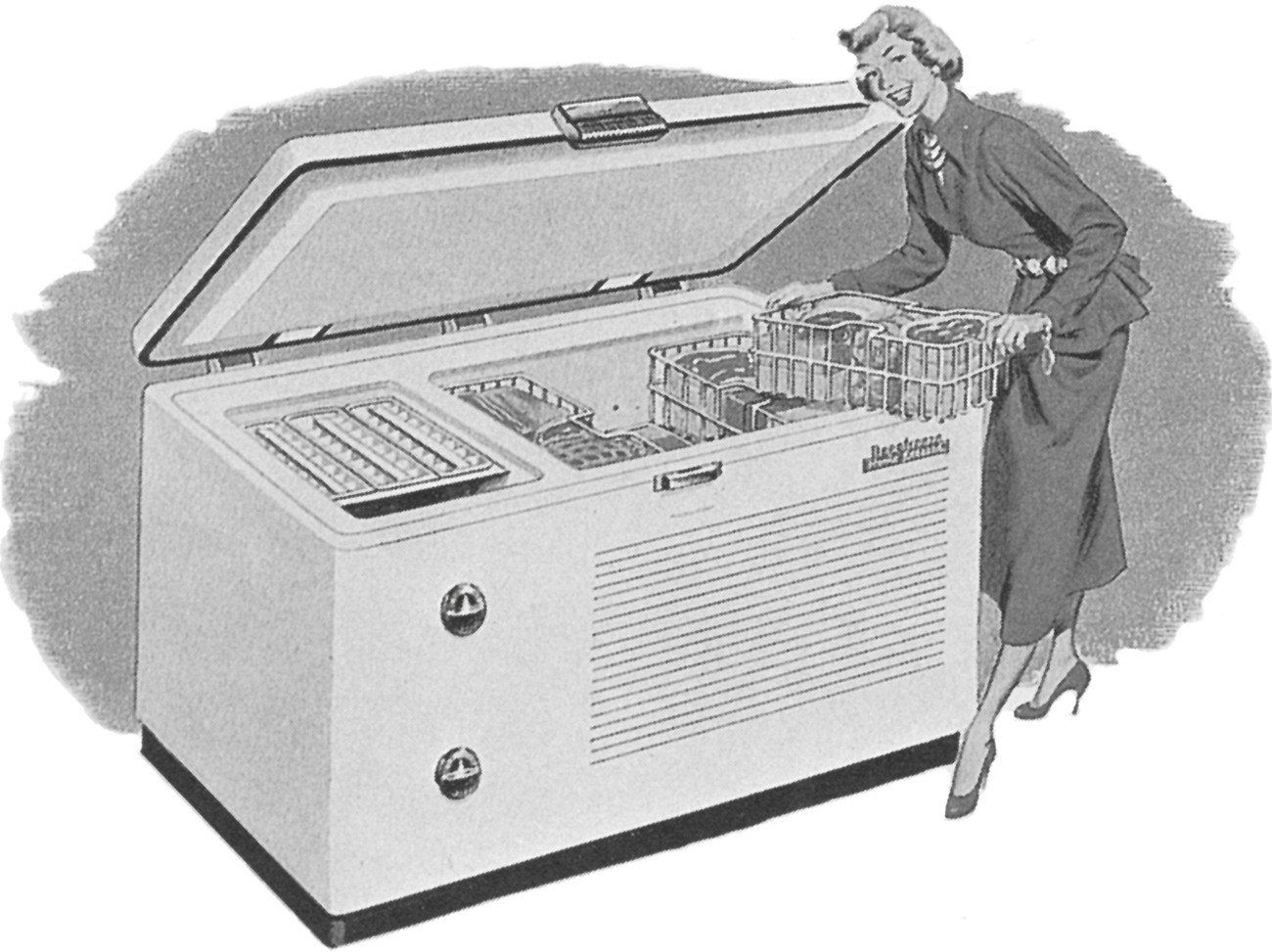

137–41 Consumerism expressed by large kitchens surfaced with brightly coloured plastic laminates, streamlined fridges, freezers, the informal breakfast bar and the family games room, and not least the family automobile.

A consumer boom, beginning in the 1950s in America and spreading throughout Europe in the 1960s, had a profound effect on the taste-making process in interior design. For the design of the domestic interior, initiative passed from the architect and interior decorator to the consumer, who now exercised a greater degree of choice than ever before, right across the social spectrum.

In the American decorating manual The Complete Book of Interior Decorating (1956), home journalists Mary Derieux and Isabelle Stevenson advised the reader to: ‘Start an indexed scrapbook in which you can collect magazine articles, advertisements of new types of equipment and furnishings, room pictures and color schemes which appeal to you.’ For the first time it was stressed: ‘Don’t be afraid to give expression to your own taste in making your selections. It is your home.’

The tradition of home advice manuals for the middle-class woman had been established in the nineteenth century. Guidance on taste could also be gleaned from a wealth of writings by designers and critics of all kinds. However, such books generally recommended one style only and criticized all other trends. In 1954 Donald D. MacMillan was advising in Good Taste in Home Decoration that ‘… the accepted standards of good taste in the field of interior design have developed over a long stretch of time and a knowledge of these standards is invaluable’. Interior decorators who were won over by the moderne during the inter-war years advocated this over all other styles. Propagandists of the modern movement tried to influence public taste through the DIA yearbooks in Britain, and in America with Museum of Modern Art exhibitions and associated pamphlets. The authority of such tastemakers was eroded during the 1950s, and the question of what constituted ‘good’ taste became confused.

In America, huge suburban sites were developed to cater for a booming middle-class population. The American family moved house more frequently than its pre-war predecessor, and needed to communicate important statements about itself and its place in a particular social milieu through the appearance of the home. The home was re-established as the province of the wife. The role of the housewife had shifted dramatically as a result of the Second World War. During the war, women in America and Britain were officially encouraged to enter the factories and take on traditionally male jobs, for example as riveters, welders and turners. A ‘make do and mend’ approach was adopted in the home. After the war, men returning from the fighting needed jobs, and the importance of the domestic role of women was reasserted by the mass media and the authorities. Dior’s New Look of 1946 reinforced a traditional role for women with its emphasis on the bust, waist and hips and unpractical stiletto heels, and the woman’s traditional job as mother and housekeeper was given greater emphasis through scientific justification. A new image of the professional housewife was constructed by the media.

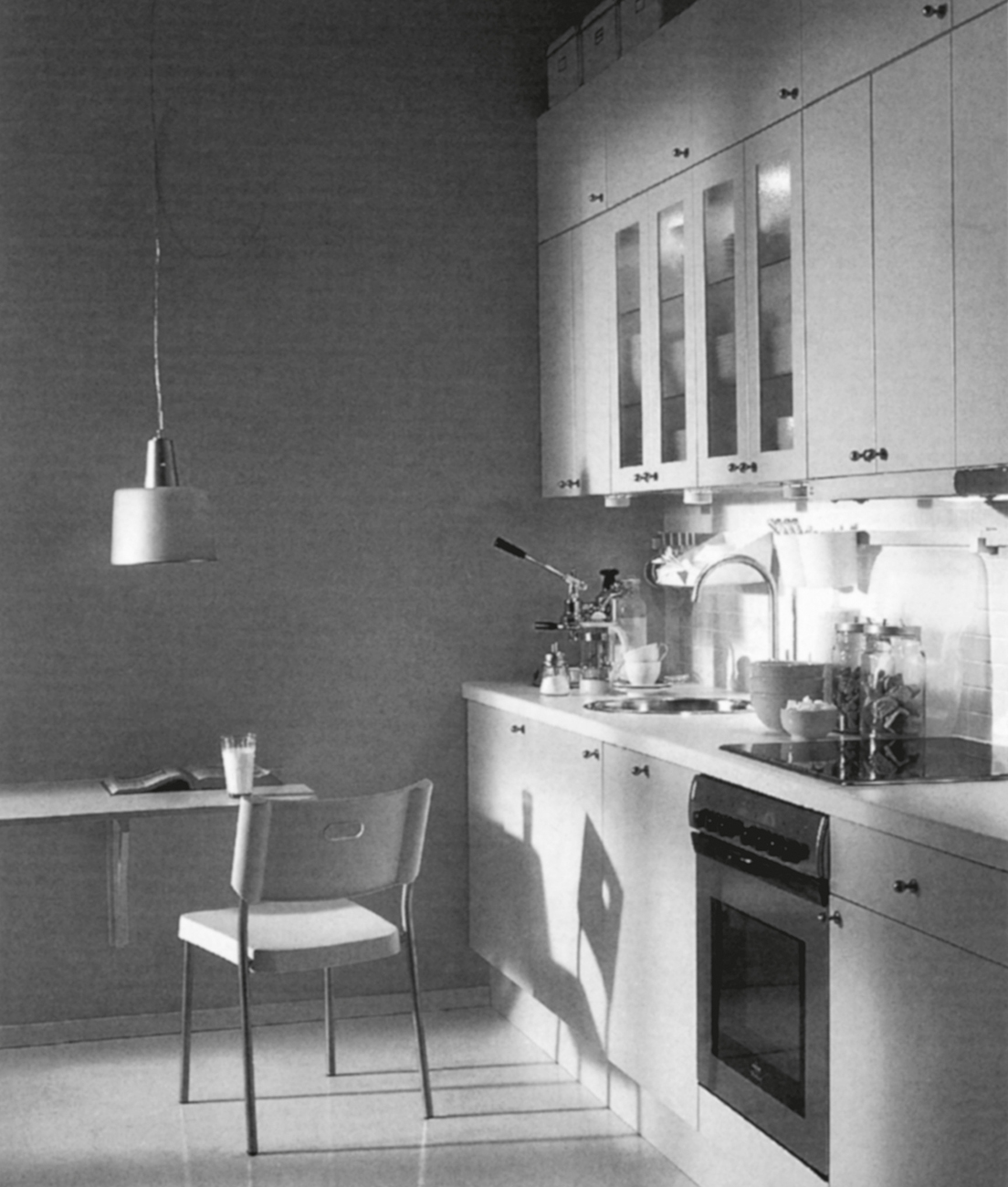

The housewife became an important target for the advertiser and manufacturer as soon as it was realized that she was responsible for handling the family budget. As David Riesman observed in his survey of American consumerism, The Lonely Crowd (1950), ‘women are the accepted leaders of consumption in our society’. This factor was important for the development of kitchen design in the post-war years. New domestic gadgets such as the electric food-mixer, toaster and kettle were accommodated in larger kitchens, with ample storage space provided by fitted units, laminated with coloured and patterned plastics. Double cookers, fridges and washing machines grew larger in America, and began to appear in British homes for the first time. The large size of such items was not functionally necessary. The design of fridges was based on car design, being streamlined, and they came in colours such as salmon-pink or turquoise with chromium trim. Manufacturers had realized the importance of design obsolescence, and the status-conscious housewife needed to be persuaded that she wanted the latest style with ‘added extras’. The servantless kitchen was no longer out-of-bounds to family and callers and needed to impress the guest. This development marked a reversal of the scientific approach of the 1930s, when kitchens were made as small as possible, being based on the ship’s galley.[137-8] Now the American kitchen provided the main focus of the domestic interior, signifying that the woman of the house was always there, that her domestic duties were paramount.

137–41 Consumerism expressed by large kitchens surfaced with brightly coloured plastic laminates, streamlined fridges, freezers, the informal breakfast bar and the family games room, and not least the family automobile.

The open-plan arrangement that was popularized by modern architects during the 1950s made the kitchen an integral part of the ground-floor living area. The living area in these new houses was larger than the pre-war equivalent, for it frequently incorporated a dining area with a ‘breakfast bar’ to divide it from the kitchen. There was interest in dual-purpose rooms.

The seating inspired by the designs of the Cranbrook Academy would now be arranged around the television set, rather than facing the fire as previously. Heating was provided by radiators, allowing a flexible furniture arrangement. Strong colours such as lime-green and orange contrasted with black were fashionable, as were standard lamps, low, boomerang-shaped tables of metal and plastic laminate, and indoor plants. The exuberance of the new consumer guaranteed a heterogeneous mixture of styles. As well as modern, ‘Old French’, Colonial and Spanish Mission styles remained popular.

Post-war prosperity and growth also brought a revolution in shopping habits and transport. Huge supermarkets were built on the edges of towns, as were drive-in cafes and cinemas, reflecting the fact that America had become a car-owning nation. The interiors of these vehicles were designed with fantasy, not function in mind. Like the contemporary kitchens, they were much larger than function demanded, with generous upholstery, and wraparound windscreens and chromed control instruments largely based on popular science fiction imagery, as exemplified in the 1954 Cadillac and 1957 Chevrolet Bel Air.[142] The interiors of jet airliners, another important new mode of transport, were more stringently controlled by space, dimensions and ergonomics. Harley Earl (1893–1969), the head of design at General Motors from 1927 to 1959, also worked as an interior designer, and when he designed the interior of the General Dynamics Convair 880, he tried to break up the monotony of the long narrow interior by making a break in the ceiling fitting on every fifth row. Foam shells formed the seating, which was crisply upholstered in blue. A scarlet aisle-carpet and white gold-flecked fabric covering the walls and ceiling provided a decorative effect.

142 Harley Earl: Cadillac interior, 1954. The styling of wheel, chrome air-vents, levers and dials owes more to science fiction and aeroplane design than to function.

The interiors of diners and bars were flamboyant, with pastel-coloured plastic seats and laminated, built-in tables with chrome fittings, in the organic shapes of post-war modernism.

The development of popular American design during the late 1940s and 1950s horrified the British design establishment who were attempting to promote a more functional style. Concerned about the continuing taste for revivals, the Council of Industrial Design launched a successful campaign to promote a new style: the Contemporary.

The most significant vehicle for the campaign was the Festival of Britain, held in 1951. This was a patriotic celebration of the past, present and future achievements of Great Britain on the centenary of the Great Exhibition of 1851. The Contemporary Style was launched by the CoID in its magazine for industry and the consumer, Design, in February 1949. The Council invited manufacturers to submit exhibits for the Festival which should be ‘lively and of today, which does not exclude those basic designs that remain as good as they have ever been, such as the Windsor chair and many hand-tools’.

Thus the Contemporary Style provided an effective blend of the latest developments in American and Swedish design with British traditions. The Contemporary Style was first seen by the public at the Festival site, where the CoID mounted an exhibition of room settings and launched the Design Index, enabling the public to browse through examples of ‘good design’ mounted on cards.

The interiors and furniture designed for the Festival site were all vetted by the Council and typify the Contemporary Style.[143-4] Chairs designed by Ernest Race and Robin Day are skeletal constructions with great stress placed on line. They are simple in that they have no surface decoration, and they have splayed legs, a feature common to all Contemporary furniture and inspired by Cranbrook designs of the 1940s. The thin chair legs rest on balls, another key feature of Contemporary-style furniture. This motif derived from the CoID’s introduction of the theme of molecular biology for the Festival Pattern Group. The Group consisted of twenty-eight British manufacturers who based textile prints, light fittings, glass and ceramics on diagrams of crystal structures: for example, the fabric ‘Helmsley’ designed by Marianne Straub for Warner and Sons Ltd was based on the chemical structure of nylon.

143 Ernest Race’s Antelope chair, designed for use throughout the Festival site.

144 ‘Contemporary’ living room, Council of Industrial Design, 1951. Officially approved British design, exhibited at the Festival of Britain in 1951.

The whimsical and decorative nature of the Contemporary Style ensured its success with the consumer. This was in no small part also due to the sustained propaganda campaign instigated by the CoID after the Festival, using women’s magazines, television and exhibitions to put the message over to the public. Each year at the Daily Mail Ideal Home Exhibition the CoID mounted a display of room settings which, it felt, represented that year’s norm of good interior design. In 1955, in the sixth of these displays, the Council furnished a flat designed by Robert and Margery Westmore in the Contemporary Style with furniture that could be bought at a high street retailer, in this case Williams Furniture Galleries, Kilburn. Such schemes were aimed at the new occupants of local authority housing. Post-war public housing generally offered smaller living spaces than its pre-war equivalent, hence the lightweight, functional pieces of Contemporary furniture were popular and replaced more solid items such as the bulky three-piece suite of the 1930s. The open-plan layout of many flats and houses ensured the popularity of the room divider, which could separate the living from the dining area. George Nelson’s upmarket prototype was manufactured in Britain by E. Gomme and Sons Ltd as part of its range of interchangeable unit furniture marketed as ‘G-Plan’ from 1953.

Many features of the Contemporary interior derived from architect-designed models. Natural elements such as indoor plants, simple varnished wood, bare brick and natural stone created an effect of lightness, airiness and functionalism. Desperately needed public housing was provided in Britain with various New Towns in order that the suburban sprawl of London and the other major cities should be halted. Crawley in Sussex was designated a New Town after the war and the show houses were furnished in the Contemporary style for working-class Londoners seeking a better quality of life away from the pollution and overcrowding of the capital.

Colour and pattern were also important features of the Contemporary interior. Wallpapers and fabrics were printed with pastel backgrounds and black linear patterns derived from modern sculpture or, for kitchens, with designs of fruits, vegetables or crockery. The Contemporary-style interior often featured the mixing and matching of very different patterns. This was encouraged by the home advice manuals, for example, in Newnes Home Management it was suggested that contrasting wallpapers of spots and stripes should be used to add interest to chimney-breasts.[145] The do-it-yourself market originated in America and flourished in America and Britain during the 1950s, encouraged by the magazine Do-It-Yourself, founded in 1957. Texas Homecare in Britain, for example, began as a family business in 1911 manufacturing wooden fireplaces. In 1954 the company opened several shops selling wallpapers and paint. In 1972 the company opened the first warehouse for the large-scale provision of materials for home improvements; by the late 1980s there were nearly two hundred such retail outlets. The market for such goods for the non-professional decorator had partly been stimulated by comparatively simple-to-use emulsion paints and vinyl wallpapers.

The widespread popularity of the Contemporary ironically led to its demise. As the mass-market demand for splayed legged plastic-laminated coffee tables increased into the 1960s, so the interest of professional designers waned. Architects were dismissive of the Contemporary as a fashionable style, to be outlived by the permanent values of modernism.

By the early 1950s the monolithic laws of classic modernism were beginning to be called into question. Members of the Independent Group, which met sporadically at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London from 1952 to 1955, dismissed modernism as outdated. Leading members, including the design writer Reyner Banham, architects Alison and Peter Smithson and James Stirling, and artists Eduardo Paolozzi and Richard Hamilton formulated a new cultural critique based on their enthusiasm for popular American design. The Group was fascinated by the American way of life as represented by the lavish interiors seen in Hollywood films and colour advertisements in magazines such as McCalls and National Geographic. Well-stocked refrigerators, automatic washing machines and televisions had an obvious appeal in the austere economic climate of Britain in the early 1950s. This avarice can be seen in Richard Hamilton’s Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing? (1956), an inventory of all the objects of mass consumption enjoyed in American homes.[146]

145 Young homemakers turn to do-it-yourself. Roller-printing with paint for contrasting patterns in pink and green.

146 Richard Hamilton’s inventory of American consumerism: Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing?, 1956.

147 Alison and Peter Smithson: ‘House of the Future’, Ideal Home Exhibition, 1956 (shown with the roof removed). Moulded room-components cluster round a central patio space.

Independent Group discussions inspired Alison and Peter Smithson to design a ‘House of the Future’ for the Daily Mail Ideal Home Exhibition of 1956, according to Reyner Banham based on the styling and marketing of American cars.[147] The Smithsons’ House was moulded in plastic in a range of colours with chromium trim, and was intended to be updated every year. Like many interiors of the 1950s, that of the house was open plan, with the function of each area defined by the built-in furniture and appliances. The House demonstrates the way in which technology was idolized during the 1950s as a means of liberating the housewife to allow her to spend more time with her family. The House created a great deal of media interest with its labour-saving devices, such as the portable electronic dust-collector, waste-disposal unit, dishwasher and gamma-ray machine for treating foods.

The Smithsons’ major achievement was to design a piece of expendable architecture. Modern movement theorists had always preached the value of an everlasting style, linking modernism with the buildings of Ancient Greece. The Smithsons believed that architects should learn from mass culture, and apply the lessons of rapidly changing styles and popular appeal to architectural design.

In the late 1950s the ‘expendable aesthetic’ began to apply increasingly to interior design. Swiftly changing fashions were inspired by a whole range of sources, but notably, not by mainstream architecture. One crucial source for new interior design was a new type of consumer. In the 1950s there was the phenomenon of the teenager. The spending power of the sixteen- to twenty-four-year-old age group had risen meteorically since the mid-1950s as young people enjoyed full employment and reasonable wages. A report commissioned by a London advertising agency in 1959 estimated the spending power of the British teenage sector in the previous year to be £900 million. The result was a new market sector that needed to make a distinct cultural statement.

Previously young people had unquestioningly assumed the style of interior offered by their parents. Now young people demanded that their own territory should symbolize their new independence. This was commonly seen in the decoration of the teenager’s bedroom within the parental home with posters, records and record player. In the 1950s the coffee bar provided a meeting place for the young in Britain. These were generally run by first-generation Italians and featured a chrome coffee machine prominently displayed on the counter. The best-known example of the espresso coffee machine was designed by Gio Ponti for Gaggia in 1949. As one of the Independent Group, Toni del Renzio, commented in 1957: ‘The espresso is doubtless part of a strong Italian influence that includes the motor-scooter and a new line in movie heroines.’ In London Douglas Fisher designed ‘The Gondola’ in Wigmore Street and the ‘Mocamba’ and ‘El Cubano’ on Brompton Road within this genre. Tables were usually covered in bright plastic laminate with aluminium trim, and the furniture was the popular Contemporary. An Alpine motif was often introduced, and walls were frequently faced in stone or decorated with stone-effect wallpaper.

The American influence was also powerful, with the totem of youth culture, the juke box, on display. Like many items of industrial design of the era in America, the 1950s Wurlitzers were based on the visual imagery of car design, with chromium plating, wrap-around screens, quasi-dashboard for selecting the records, and even red lights and tailfins. The affluence of American teenagers in comparison with those of Europe was marked by new drive-in fast-food outlets designed for the age group.

Design for the youth market exploded in the 1960s with even greater affluence and a new feeling of breaking down the barriers of conventional social mores. This was expressed in the pop design movement which first emerged in Britain as part of the general pop movement. In 1963 the Beatles had three number one hits in Britain, and their American tour in the following year established British dominance as world leader of youth culture. This manifested itself in interior design with the creation of new environments for the youth market, such as the boutique, a small shop selling inexpensive, trendy clothes exclusively for the young. The first, Bazaar, was opened by fashion designer Mary Quant (b. 1934) in King's Road, Chelsea, in 1955. She moved to a new shop in Knightsbridge in 1957, designed by Terence Conran (b. 1931), featuring a central staircase with the clothes hanging beneath, and bales of fabric decorating the upper parts of the interior. By the mid-1960s these small shops had opened in cities throughout Britain. In 1964 Barbara Hulanicki (b. 1936) opened the first Biba shop off Kensington High Street in London.[148] The interior was dimly lit and pop music played loudly the whole time. The walls and floor of the Biba stores that followed were decorated in dark tones, the clothes hung on bentwood Victorian hat stands, and ostrich feathers in nineteenth-century vases added to the decadent atmosphere.

148 Biba, London, 1972. Art deco motifs and Victorian bentwood hat stands evoke an ambience of ‘retro-chic’ in Barbara Hulanicki’s first Kensington High Street store.

The need for young people to dissociate themselves from the older generation and communicate fun and transience explains the diverse inspirations for pop. The decorative styles of the past were revived, particularly art nouveau after an exhibition of Aubrey Beardsley’s work at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1966, and art deco, encouraged by the publication of such books as Bevis Hillier’s Art Deco of the Twenties and Thirties in 1968, and films such as Bonnie and Clyde (1967). The aim was not to replicate past styles but incorporate them into a new, young look. Victorian furniture, reviled by serious connoisseurs of the decorative arts, was painted in bright gloss, and the new art of the poster was largely inspired by Aubrey Beardsley and Alphonse Mucha. Biba moved into the art deco former Derry and Tom’s department store in the early 1970s, with retro, glamorous interiors by film-set designers.

‘High Art’ and mass culture now developed into one intermingled area. The pop art movement had begun in the early 1960s on both sides of the Atlantic with the work of artists such as Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol in America and David Hockney and Allen Jones in Britain. The fine artists themselves took mass culture as their source of inspiration. Lichtenstein for instance reproduced the effect of the cheap printing of comic books in his paintings, which are made up of an overall pattern of dots.

Images taken from pop art were in turn used for posters, inexpensive crockery and murals. The exchanges operated on every level, as Warhol designed wallpaper with cows printed on it and furnished his studio, The Factory, in New York, with plastic silver clouds filled with helium. At the exhibition ‘Four Environments by New Realists’ held in 1964 at the Sidney Janis Gallery, New York, the pop sculptor Claes Oldenburg exhibited a bedroom setting that is an acknowledgement, if not a celebration, of consumer culture, with white vinyl satin sheets on the bed and a fake zebra-skin couch with a fake leopard-skin coat thrown over it. Oldenburg’s soft sculptures of objects such as huge stuffed hamburgers were translated into furniture design, and cheap reproductions of his work were available at high street furniture shops for the youth market as late as 1988. The basement of the new Biba store by Witmore-Thomas featured gigantic mock baked-bean and soup tins on which were shelved real tins of food.

The op art movement was also to affect interior design. The movement originated in France with Victor Vasarely (1908–1997) and was developed in England by Bridget Riley (b. 1931), who painted black-and-white images designed to dazzle the spectator by giving the illusion of movement. Such images inspired television set-design for the programme Top of the Pops and boutiques, and generated a healthy poster trade.

Students at the Architectural Association in London had tired of the staid, permanent laws of the modern movement. The Archigram Group, led by Peter Cook, released its first statement in 1961 expressing dissatisfaction with modernism and support for a more organic, free-flowing architecture.[149] In later statements the Group declared an interest in the possibilities of an expendable architecture that could be adapted to suit the individual occupant. In Florence, the Archizoom group, formed in 1966 and led by the architect-designer Andrea Branzi (b. 1938), made a similar foray into pop art aesthetics in 1967 with various beds that incorporated art deco motifs, images of pop stars and fake leopard-skin to indicate their allegiance to mass culture as opposed to the traditional high culture of architecture.[150]

Pop design’s challenge to notions about tradition and longevity was further emphasized by the production of disposable furniture. The lack of seriousness and playfulness of pop created an atmosphere in which furniture could be made from sturdy card, assembled by the purchaser, enjoyed for a month or so and then discarded as the next model appeared. A paper chair by Peter Murdoch, in a simple bucket shape and brightly decorated with polka dots, was mass produced in 1964 for the British youth market and had an expected life-span of three to six months.

149 Archigram Group: design for an automated house.

150 Archizoom Associates: ‘Dream Bed’, 1967. An Italian architectural partnership deliberately flout the canons of good taste with a mixture of art deco and pop motifs.

151 Chelsea Drugstore, by Garnett, Cloughley, Blakemore Associates, 1969. A deliberately disorientating interior of aluminium capsules.

Disregard for environmental issues was a characteristic of pop. In the early to mid-1960s the consumer and designer were wholly optimistic about scientific achievements. There was a definite pro-technology dimension to the pop interior, which exploited the possibilities of new materials and techniques. The Chelsea Drugstore in King’s Road by Garnett, Cloughley, Blakemore Associates (1969) used polished aluminium for its interior to create a spaceship atmosphere, enhanced by purple graphics in the style of a computer printout to indicate different areas within a large building.[151]

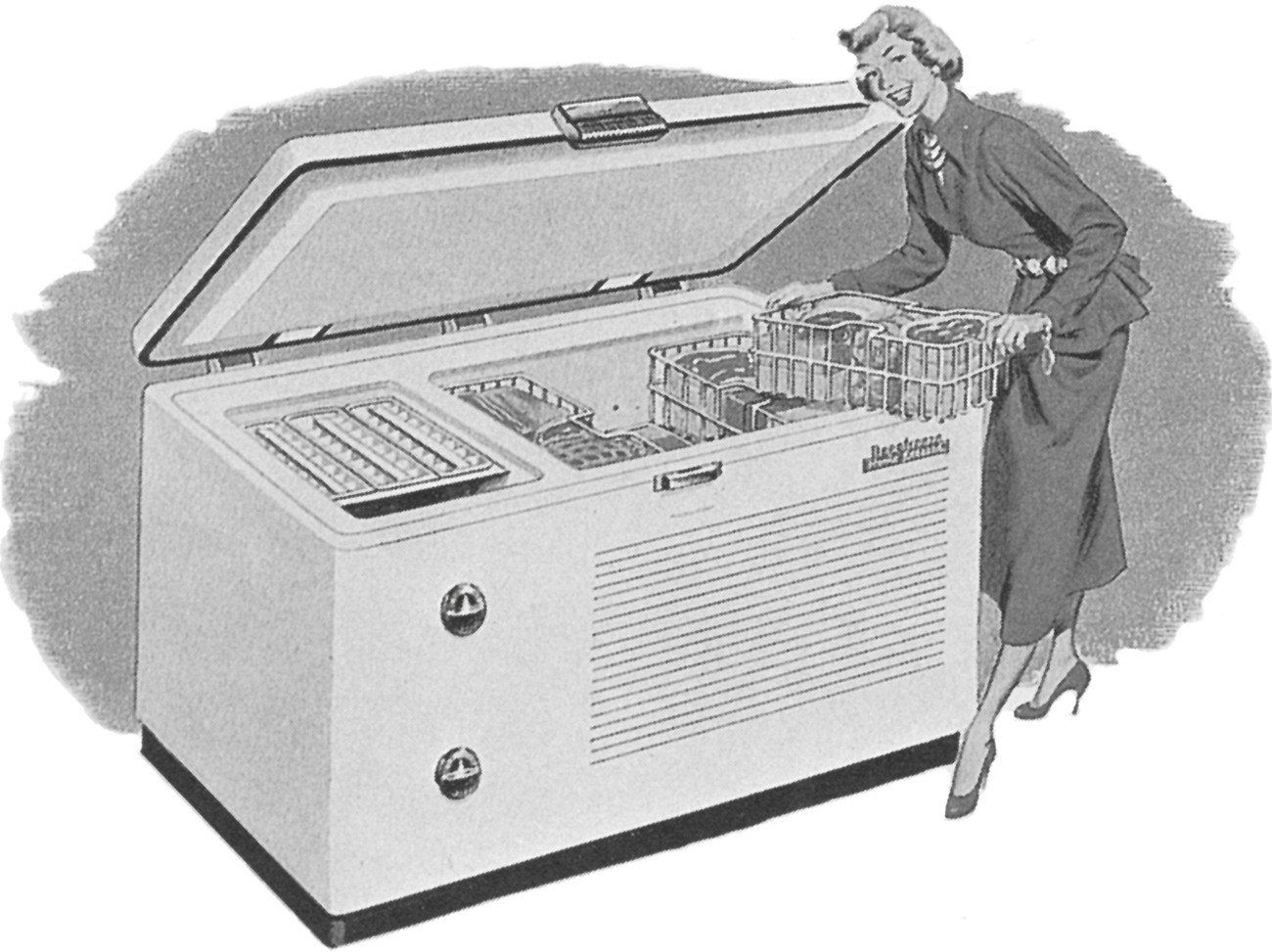

152 Olivier Mourgue: ‘Djinn’ seating, as used in the film 2001: A Space Odyssey, 1967. Biomorphic forms based on a steel frame, foam padding and jersey-nylon covering: the 1960s flexible furniture shapes.

In France, the interior designer Olivier Mourgue (b. 1939) created futuristic sets for the cult film 2001: A Space Odyssey, furnished with his low, curved seating based on exaggerated amoeboid forms.[152] The gently curved chaise longue ‘Djinn’ (1964) won him the AID International Design Award.

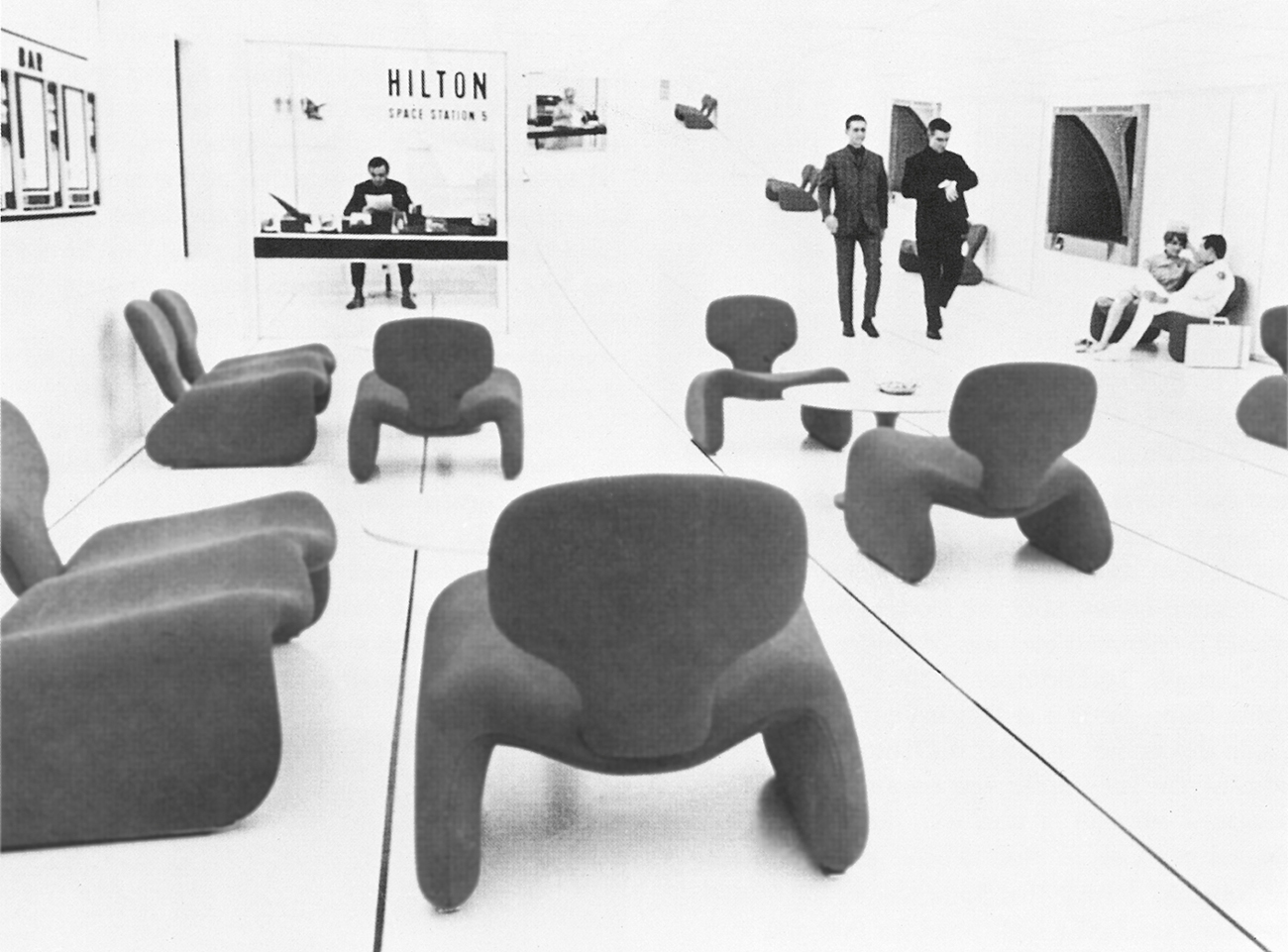

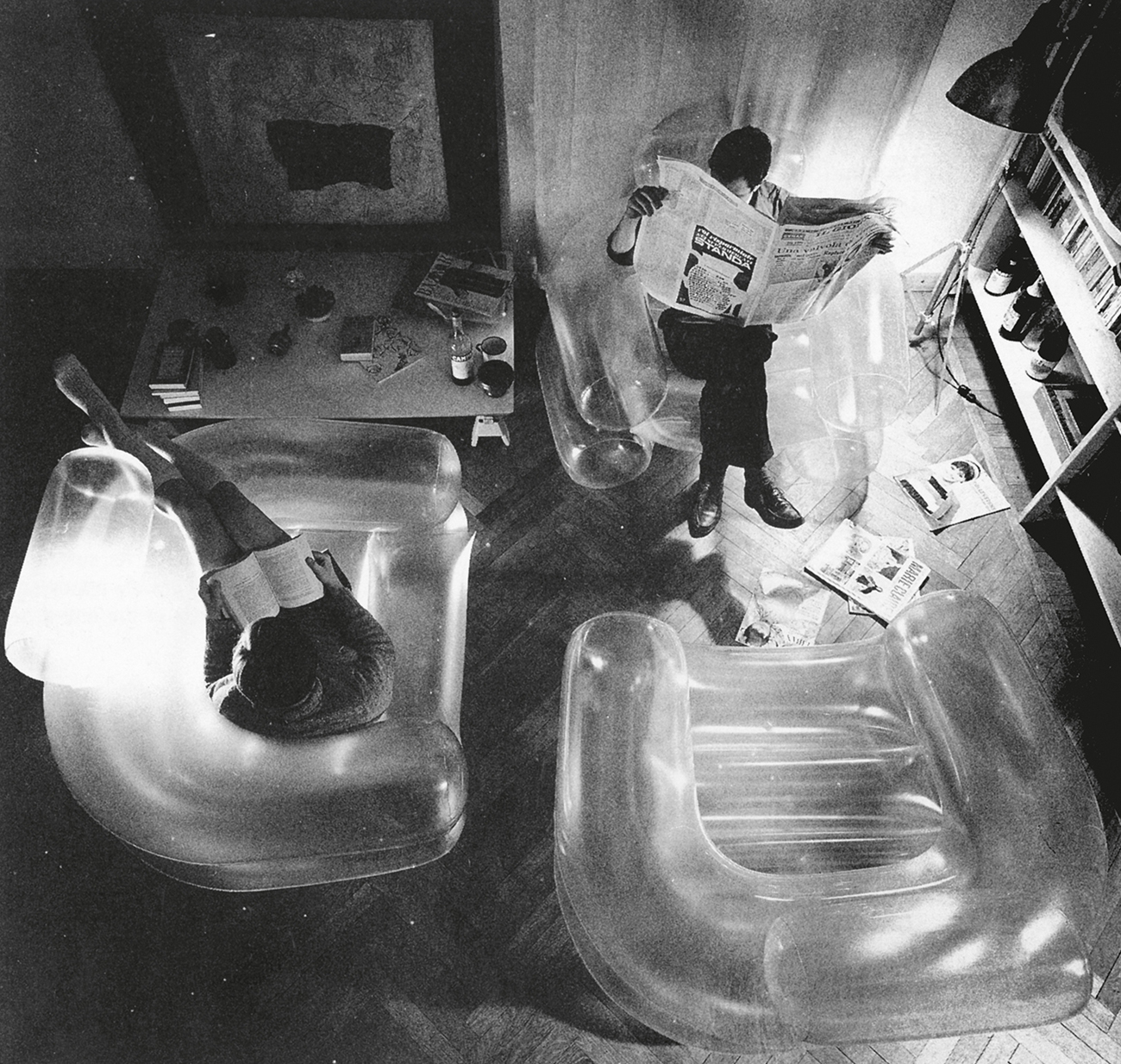

In Italy there was a marked reaction against mainstream modernism in the later 1960s, and young designers created interiors and furniture that deliberately challenged the canons of ‘good taste’. The ‘Sacco’ seat designed by Gatti, Paolini and Teodoro for Zanotta in 1970 was simply a sack filled with polyurethane granules, adaptable and formless. Zanotta also manufactured early inflatable furniture with the ‘Blow’ chair by Lomazzi, D’Urbino and De Pas in 1967. Manufactured in clear PVC for use in swimming pools, its fun and anti-establishment connotations appealed to young consumers in France and Britain.[153] The same trio of designers was responsible for ‘Joe Sofa’, also manufactured by Zanotta in 1971 and consisting of a polyurethane-foam hand covered in soft leather in imitation of a glove. This fun furniture was inspired by the soft sculpture of Claes Oldenburg.[156] The leading pop interior designer in Britain was Max Clendinning (b. 1924), who designed ‘knock-down’ furniture and total environments that relied on the use of one colour for their effect. His design for a living room, published by the Daily Telegraph in 1968, consisted of smooth, integrated solids for chairs, stools and tables, and storage space that was inspired by the excitement generated by space travel.

The appeal of new technology was accentuated with the first moon landing in 1969. Whole interiors were designed around a space age theme, with computer typeface and metallic or brightly coloured plastic facings.[157] The living room of Victor Lukens in New York (1970) incorporates all these features and includes an enclosed seating unit from which the occupant can observe the room without being seen.

153–5 The informality of the 1960s living room exemplified by soft seating. ‘Joe Sofa’, inspired by Claes Oldenburg’s ‘soft sculptures’. the ‘Sacco’ of 1970 and the ‘Blow’ chair of 1967. Pop furniture mass-manufactured by Zanotta. Some shelves hung on painted walls or stacked on bricks, a bright-coloured moulded plastic table and a floor/table lamp were basics to be added.

156 Max Clendinning: dining room of the designer’s own house, London, 1960s. Ceiling colours continue down the walls, horizontal stripes defy corners to expand space. Chair arms and backs are designed to be unbolted and exchanged for new shapes.

157 Victor Lukens: living room, New York, 1970. The 1960s bubble chair, here in a oneway-mirror version, in the designer’s own apartment of shiny moulded plastic and vinyl. Niches cut in the walls hold lights and television/sound equipment.

The creation of deliberately disorientating interiors was a product of a new drug culture. Drugs that altered the perception, especially LSD, were associated with pop culture and gave rise to the Psychedelic movement. The normal dimensions of a room were obliterated by light shows, or by supergraphics which often imitated their effect.

In America Barbara Stauffacher Solomon popularized the use of large-scale graphics for the decoration of interiors with the Sea Ranch Swim Club (1966) in Sonoma, California.[158] Lettering was blown up and randomly mixed with bold stripes and geometric shapes in primary colours to conflict with the architectural space and produce a disorientating effect. In Britain, huge amoeboid shapes in bright, even fluorescent colours, spread randomly over ceilings, walls, doors and floors, as in the Junior Common Room at the Royal College of Art, designed by the students in 1968. There was also ‘The Retreat Pod’, designed by Martin Dean, which completely enclosed the occupant in an egg shape to encourage transcendental experiences. This type of interior had its ultimate expression in the sensory deprivation tank. The ‘Trip Box’ by Alex MacIntyre, a hallucinatory environment created with back-projection and music, was shown by the London furniture store Maples, in 1970, in an exhibition entitled ‘Experiments in Living’.

158 Barbara Stauffacher Solomon: ‘Supergraphic’, Sea Ranch Swim Club, Sonoma, California, 1966. The artist’s bold red, blue stripes and graphics counterpoint the architectural space.

159 The 1960s conversation pit, suited to the relaxation of lifestyles and mores. Psychedelic neon (left), flexible tube lighting and giant stand-up electric light-bulbs were all popular 1960s–1970s designs.

Pop design inspired film sets, particularly those of Barbarella and Help, which introduced a carpeted seating-well. Effects such as these could be easily emulated at home and featured in previously staid magazines like Vogue and House and Garden.

There were strong links between pop and surrealism. The bizarre juxtaposition of incongruous objects in deliberate ‘bad taste’ in strangely lit, brightly coloured interiors stems from the language of Dada and surrealism. Previous proponents of surrealism like the critics Mario Amaya and George Melly were now deeply involved in pop. It is also an indication of the continuing importance of fine art for interior design, as the preferred alternative to architecture, which had anyway been discredited by movements like Archigram. The architectural elements melted away, as the room became an environment, a happening or a painting. The mural was a key feature of the pop interior. George and Patti Harrison commissioned the Dutch ‘Fool’ group of designers and artists to paint a psychedelic circular mural above the fireplace of their new bungalow in Esher, Surrey.

The brash, dayglo colours of the mid-1960s were tempered towards the close of the decade as concern about the environment became an issue. A new spiritual and political consciousness characterized youth culture, as a deliberately ‘Alternative’ set of rules was evolved. After the revolutions and student protests of 1968 and the Torrey Canyon oil-spillage disaster, young people were no longer pro-technology and sought ways to reject conventional Western values as hippies.

In terms of interior design, it was important to state your allegiances through the look of your home. Some abandoned permanent homes altogether for a nomadic lifestyle, preferring caravans or tent structures. In more permanent domiciles there was the introduction of artefacts from the Third World, particularly from India, natural materials, real fires, candle-light and patterned textiles and wallpapers. The Whole Earth Catalog, edited by Stewart Brand from 1968, provided such ecologically sound paraphernalia. One’s room became a self-conscious political statement, whereas previously it had simply been fun. The book Underground Interiors: Decorating for Alternate Life Styles (1972) typifies this trend. The authors described it as ‘an exploration into the revolt against old concepts of decor and old ways of living – a look at the new living environments closely linked to recent developments in art, politics and the press, all of which have taken the name “underground” to distinguish them from their establishment counterparts.’ Whether ‘radical chic’, space age or surreal, these are anti-establishment interiors.

The return to nature was catered for by a new store called Habitat.[160] Founded by Terence Conran, the first shop opened in May 1964 in London to sell ‘good’ basic design to the middle-class market. The chicken brick, rush matting and beech furniture became standard in the early 1970s for the creation of a total lifestyle. The design of the shop itself was influential, with white-painted walls and a brown quarry-tiled floor. The goods were displayed en masse to give the impression of a warehouse. Significantly, Habitat also marketed classic modern movement chairs, signifying a shift in taste away from the exuberance of the 1960s. As the economic recession deepened young consumers rejected the freedom and transience of the 1960s.

160 Habitat, London, 1972. By the early 1970s Terence Conran’s store was marketing a quiet, tasteful but commercial modernism.

One of the most lasting trends in late twentieth-century interior design was environmentally friendly or green design. This term emerged during the early 1970s, firstly in Germany, and signified an alternative and more caring approach to natural resources. The green movement was driven initially by minority political concerns and involved using consumer power. American designer Victor Papanek’s (1923–1998) best-selling book, Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change, was first published in 1972 and acted as a critique of Western design practices, particularly built-in obsolescence, and advocated striving to meet consumer needs rather than wants. The book caused outrage among the design establishment.

It was not until the mid-1980s that green design and green politics shed their alternative image due to scientific research and legislation in support of an environmentally responsible approach. Green design became part of mainstream interior design practice and informed patterns of consumption. The recycling of household waste became the norm and consumers sought out environmentally friendly products. A public concern for green issues affected producers on a global scale. For example, the Valdez incident of March 1989, when a giant supertanker ran aground, spilling 10 million gallons of oil, which polluted 700 miles of coastline and devastated the wildlife, prompted the Valdez Principles. This set of guidelines was created by a multinational Coalition for Environmentally Responsible Economies (CERES), consisting of environmentalists and ethical investment organizations. The principles included protection of the biosphere, reduction and disposal of wastes, sustainable use of natural resources and energy conservation.

Green design has had an impact on the types of materials employed in interiors and on how space is used to create more environmentally friendly surroundings, making efficient use of natural light and sources of power. For example, a house designed by Javier Barba (b. 1949) in Llavaneres, at Maresme in Catalunya, Spain (1984–6), is partly buried in a hillside.[161] It is well insulated by the turf, which covers the roof and blends into the garden; the main living area features a south-facing, curved window to exploit the available solar energy fully and tiled floors help to retain heat. The form of the interior is thus dictated by environmental concerns, particularly energy conservation. It is not only the careful management of finite sources that has made an impact on interior design, but also the need to create healthier working environments, particularly with the discovery of sick building syndrome in the 1980s. The need to ensure good systems of ventilation and natural sources of light, and to monitor the use of hazardous materials became central in the design of the workplace. The interiors of new office buildings, notably Niels Torp’s (b. 1940) Scandinavian Airways headquarters building near Stockholm, Sweden (1988), frequently feature a well-lit, central atrium.[162] This enables occupants to enjoy the benefits of natural daylight, as offices either face outwards or overlook the central area, and of enhanced communication as workers circulate through the main walkway. The central atrium offers the opportunity to bring the external environment into the interior, another key feature of green design.

161 Javier Barba: semi-buried house in Llavaneres, at Maresme in Catalunya, Spain, 1984–6. In the main living area the design of the interior is determined by energy-saving features, such as the curved, south-facing window and heat-retaining floor tiles.

The atrium at the former corporate headquarters of PHICO (Pennsylvania Health Insurance Company) Group in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania (1976) features decorative greenery on the balconies, which overlook the central area.[163] Likewise, in shopping malls such as Frank Gehry’s (b. 1929) Santa Monica Place in California (1979–81) or the one in Madrid illustrated overleaf, huge trees punctuate the internal space.[164] In the domestic interior, a similar theme of nature working in harmony with the internal space of a building emerged as part of green design.[165] A weekend retreat (1999) designed by Takayuki Murakami and Mira A. Locher in Nasu, Japan, is arranged around a central courtyard, which features a mountain cherry tree. The rustic simplicity of the dwelling is enhanced by the walls, which have been treated with a rough mixture of ochre plaster mixed with straw and sand, contrasting with the cherry flooring and plywood veneer skirting boards. A house designed by British architect Bill Dunster (b. 1960) for himself features a triple-height conservatory on its south-facing facade that provides a space in which to grow plants and vegetables, and also an environmentally friendly living space, heated by solar energy.[166]

162 Niels Torp: Scandinavian Airways headquarters near Stockholm, Sweden, 1988. The trend to provide a more conducive working environment has led to the widespread use of atria, such as this, for new office buildings.

163 Metcalf and Associates with Keyes Condon Florence: PHICO Group corporate headquarters, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, 1976. The ambience created by this atrium is enhanced by the natural greenery that adorns the balconies.

The ethics of green design have also been applied by home-furnishing retailers to their goods. In 1989 Habitat ceased selling furniture made from tropical hardwoods because of global concern about deforestation and instead their materials included rattan, which is derived from sustainable forests in Indonesia. In 1993 the Swedish home furnishing retailers IKEA bought Habitat; they are owned by the same founder, but operate as separate companies. Now a hugely popular mid-to-low-range global chain, IKEA has over 355 stores in twenty-nine countries worldwide, including India and Russia. With a similar commitment to green design, they only use environmentally friendly materials. For example, no cadmium is permitted in IKEA designs, as this heavy metal is both harmful and indestructible. They also sell organic cotton and linen furnishing products.

164 Typical 1980s shopping centre in Madrid, Spain, which uses plants in the atrium.

165 Takayuki Murakami and Mira A. Locher: weekend retreat, Nasu, Japan, 1999. The central courtyard is built around a mountain cherry tree and the interior blurs the distinction between nature and habitat.

166 Bill Dunster: Hope House, East Molesey, Surrey, 1993. This owner-designed home features an energy-efficient, three-storey-high conservatory where plants can be successfully grown.

IKEA’s mix of reasonably priced, high-styled design displayed in massive, out-of-town superstores, with carefully constructed room sets, is extremely successful. The adventurous designs are created by a Copenhagen-based consultancy, Pelikan, which acts as a design laboratory. Part of IKEA’s success derives from the interactive relationship established with its consumers. The stores stimulate desire by offering a wide range of styles to suit different consumer identities and by promoting a do-it-yourself ethos.[167] For example, in Britain, twelve types of fitted kitchen are offered in glossy modern or traditional wooden finishes at a reasonable price and customers are lauded in promotional material: ‘One reason why even the solid-wood door fronts at IKEA are so astonishingly cheap is that customers assemble them at home… The job is ideal for a single weekend.’ The personalizing of individual space by the consumer acting as their own designer was one of the most prominent trends in late twentieth-century interior design. It was capitalized upon by such stores as IKEA and also through books, magazines and television programmes, most notably Changing Rooms. Produced by the BBC, in this magazine programme two sets of neighbours, friends or relatives redecorated one room in each other’s homes. An interior designer oversees the process, and part of the entertainment came from observing the tension between the amateurs and the professional. Considerable efforts were made to fit the interior to the inhabitants, to express individual tastes and identities.

167 IKEA ‘Appläd’ fitted kitchen, 2000. Stylish and simple to assemble, the Swedish furniture giant offer environmentally friendly goods for the active consumer.

Globalization in the 1990s inspired taste and the expression of identity in interior design. The speed of communication enabled by new technology, particularly the internet, and increased international travel raised popular awareness about design style and ethics. The Chinese art of feng shui – the organization of interior spaces around geomantic principles – is now immensely popular for both domestic and commercial interiors.

Design is a much more public concept today and consumers take a far more direct interest in the interior design process. Since the early 1970s interior design has existed as a specialization for the architect and as a profession in its own right: interior design can again be taken seriously and involve the consumer directly. And even if interior design is not permanent, it makes a statement of sorts about the inhabitant. The new self-consciousness in interior design has manifested itself in myriad styles and, since the early 1970s, made an important contribution to the creation of a post-modern aesthetic.