In 1095, preaching at Clermont in central France, Pope Urban II set in motion a movement that would transform the political, religious and economic map of the Mediterranean and Europe. His theme was the shame heaped on Christendom by the oppression of Christians in the Muslim East, the defeat of Christian armies fighting the Turks and the scandal that the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, the site of Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection, should now be in Infidel hands.1 What Pope Urban intended as a recruitment speech summoning southern French volunteers to go east and aid Byzantium against the Turks was understood as an appeal to the knighthood of Christendom to cease fighting one another (which they did in peril of their souls), and to direct their force against the Infidel, united in a holy pilgrimage, under arms, in the sure knowledge that those who died on the great journey would earn eternal salvation. Here was an opportunity to substitute for acts of penance imposed by the Church an act for which no one was better suited than the knightly class – warfare, but this time in the service of God. Only gradually did the concept of remission of all past sins for those who joined a crusading campaign become official doctrine. But popular understanding of what the pope had offered, in the name of Christ, leaped ahead of the more cautious formulations of the canon lawyers.

The principal route followed by the First Crusade bypassed the Mediterranean and took the army overland through the Balkans and Anatolia; many crusaders never saw more of the sea than the Bosphorus at Constantinople until, much reduced in numbers through war, disease and exhaustion, they reached Syria.2 And even in the East their target was not a maritime city but Jerusalem, so that its conquest in 1099 created an enclave cut off from the sea, a problem which, as will be seen, only Italian navies could resolve. Another force left from Apulia, where Robert Guiscard’s son Bohemond brought together an army. The Byzantines wondered whether he was really planning to revive his father’s schemes for the conquest of Byzantine territory, and so, when he reached Constantinople, he was pressed to acknowledge the emperor’s authority, becoming his lizios, or liegeman, a western feudal term that was used because Bohemond was more likely to feel bound by oaths made according to his native customs than by promises made under Byzantine law. When in 1098 he established himself as prince of Antioch, a city only recently lost by the Byzantines to the Turks, the imperial court made every effort to insist that his principality lay under Byzantine suzerainty. It was amazing that a vast rabble of men, often poorly armed, proved capable of seizing Antioch in 1098 and Jerusalem in 1099, though the Byzantines were more inclined to regard this as a typical barbarian stroke of fortune than as a victory masterminded by Christ. Seen from Constantinople, the outcome of the crusade was not entirely negative. Western knights had installed themselves in sensitive borderlands between Byzantine territory and lands over which the Seljuk Turks and the Fatimid caliphs were squabbling.

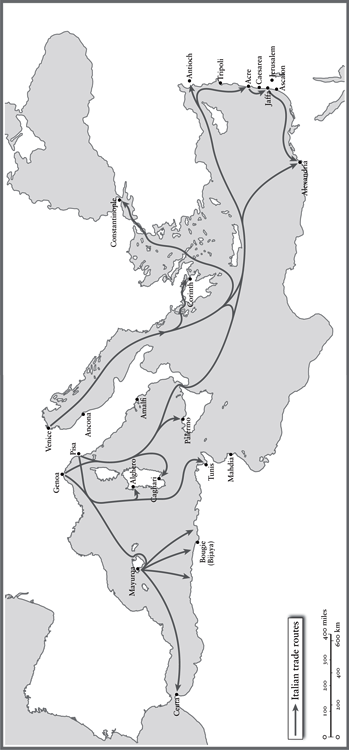

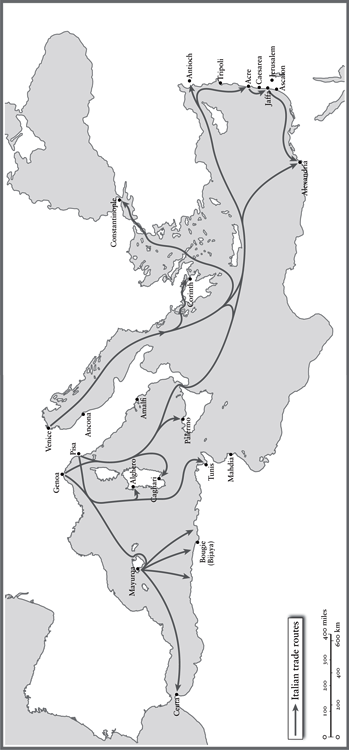

Bohemond’s religious motives in joining the crusade should not be underestimated, but he was a pragmatist: he saw clearly that the crusader armies would be able to retain nothing without access to the Mediterranean, and without naval support from Christian fleets capable of keeping open the supply-lines to the West. He would therefore need to build ties with the Italian navies. He could count on the enthusiasm that had been generated in Genoa and Pisa by the news of Pope Urban’s speech, conveyed to the Genoese by the bishops of Grenoble and of Orange. The citizens of Genoa decided that the time had come to bury their differences and to unite in a compagna under the direction of six consuls; the aim of the compagna was primarily to build and arm ships for the crusade. Historians have long argued that the Genoese saw the crusade as a business opportunity, and that they were hoping to secure trade privileges in whatever lands the crusaders conquered comparable to those the Venetians had recently acquired in the Byzantine Empire. Yet they could not foresee the outcome of the crusade; they were willing to suspend their trading activities and pump all their energy into the building of fleets that were very likely to be lost far away in battles and storms. What moved them was holy fervour. According to a Genoese participant in the First Crusade, the chronicler Caffaro, even before it, in 1083, a Genoese ship named the Pomella had carried Robert, count of Flanders, and Godfrey of Bouillon, the first Latin ruler of Jerusalem, to Alexandria; from there they had made their way with difficulty to the Holy Sepulchre, and had begun to dream of recovering it for Christendom.3 The story was pure fancy, but it expresses the sense among the Genoese elite that their city was destined to play a major role in the war for the conquest of Jerusalem.

Twelve galleys and one smaller vessel set out from Genoa in July 1097. The crew consisted of about 1,200 men, a sizeable proportion of its male population, for the overall population of the city of Genoa may have been only 10,000.4 Somehow the fleet knew where the crusaders were, and made contact off the northern coast of Syria. Antioch was still under siege, and the Genoese fleet stood off Port St Symeon, the outport of the city that had functioned as a gateway to the Mediterranean since the Bronze Age.5 After the fall of Antioch in June 1098, Bohemond rewarded the Genoese crusaders with a church in Antioch, thirty houses nearby, a warehouse and a well, creating the nucleus of a merchant colony.6 This grant was the first of many that the Genoese were to receive in the states created by the crusaders. In the early summer of 1099 members of a prominent Genoese family, the Embriachi, anchored off Jaffa, bringing aid to the crusader army besieging Jerusalem – they dismantled their own ships, carrying the wood from which they were built to Jerusalem for use in the construction of siege engines. And then in August 1100 twenty-six galleys and four supply ships set out from Genoa, carrying about 3,000 men.7 They made contact with the northern French ruler of the newly established kingdom of Jerusalem, Baldwin I, and began the slow process of conquering a coastal strip, since it was essential to maintain supply-lines from western Europe to the embattled kingdom. They sacked the ancient coastal city of Caesarea in May 1101.8 When the Genoese leaders divided up their loot, they gave each sailor two pounds of pepper, which demonstrates how rich in spices even a minor Levantine port was likely to be. They also carried away a large green bowl that had been hanging in the Great Mosque of Caesarea, convinced that it was the bowl used at the Last Supper and that it was made of emerald (a mistake rectified several centuries later when someone dropped it, and it was found to be made of glass).9 Since the bowl is almost certainly a fine piece of Roman workmanship from the first century AD, their intuitions about its origins were not entirely wrong. It was carried in triumph to the cathedral in Genoa, where it is still displayed, attracting attention as one of several candidates for the title Holy Grail.10

The green bowl was, for the Genoese, probably as great a prize as any of their commercial privileges, all of which were celebrated in the city annals as signs of divine bounty. The Genoese made friends with the rulers of each of the crusader states (Jerusalem, Tripoli, Antioch) that needed help in gaining control of the seaports of Syria and Palestine. In 1104 their fortunes were further boosted by the capture of the port city of Acre, with an adequate harbour and good access into the interior. For most of the next two centuries, Acre functioned as the main base of the Italian merchants trading to the Holy Land. The Genoese produced documents to show that the rulers of Jerusalem promised them one-third of the cities they helped conquer all the way down the coast of Palestine, though not everyone is convinced all these documents were genuine; if not, they are still evidence for their vast ambitions.11 They were even promised a third of ‘Babylonia’, the current European name for Cairo, for there were constant plans to invade Fatimid Egypt as well. To all this were added legal exemptions, extending from criminal law to property rights, that separated the Genoese from the day-to-day exercise of justice by the king’s courts.12 The Genoese insisted that they were permitted to erect an inscription in gilded letters recording their special privileges inside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Whether or not this inscription was ever put in place, the demand for such a public record indicates how determined the Genoese were to maintain their special extra-territorial status in the kingdom of Jerusalem, which never developed a significant navy of its own.13

The Genoese had competitors. The Pisans were also enthusiastic about the crusade, sending out a fleet in 1099 under their archbishop, Daimbert. They were rewarded for their help in seizing Jaffa, in 1099, and were able to set up a trading base there.14 The slowest of the three Italian cities to provide aid to the crusaders was Venice. The Venetians were aware that the Byzantine emperor did not view with equanimity the arrival in Constantinople of hordes of western crusaders, hungry and ill-equipped. They also did not want to place at risk the Venetian merchants trading in Fatimid Alexandria. Yet, seeing what bounty the crusade had brought the Genoese, they eventually sent up to 200 ships eastwards. The first stop was the small, decayed town of Myra in southern Asia Minor, where they dug for the bones of St Nicholas, the patron saint of sailors. The Venetians were jealous that in 1087 a group of sailors from Bari had managed to steal away from Myra with the bones of St Nicholas, around which they erected a magnificent basilica of white stone. Thereafter Bari, which was well placed as a departure point for pilgrims wishing to reach the Holy Land, had become an important pilgrim centre in its own right. The Venetians found enough human remains to build the Church of San Niccolò around them on the Venetian lido.15 After Myra, they turned their attention back to the crusade. Their main task was to help the crusaders attack Haifa; its sack in 1100 was accompanied by horrific massacres of its Muslim and Jewish population.16 This gave the crusaders control of the whole bay curving round from Mount Carmel to Acre. Most of the coast of Palestine was in their hands by 1110, though Ascalon was held by the Egyptians until as late as 1153.17 Egyptian tenure of Ascalon actually served the interests of the Italians, since their navies were needed so long as enemy forces persisted along the coast of the Holy Land, and the greater the need for their fleets, the better the privileges they could hope to squeeze out of the royal court in Jerusalem.

The Italians could congratulate themselves. Trade obviously flourished in times of peace, but in war too there were excellent business opportunities: the seizure of booty and of slaves, the provision of armaments (often to both sides), pirate raids against enemy shipping. It was not, however, easy to balance support for the Latin kings of Jerusalem against other ties and commitments, especially in Egypt and Byzantium. The Byzantine emperor began to wonder whether he had given the Venetians too much. In 1111 the Pisans were granted a limited set of commercial privileges, and then in 1118 Alexios Komnenos’ son and successor, John II, refused to renew the Golden Bull granted to Venice in 1082. He should not have been surprised when the Venetians looked elsewhere; they showed a new burst of enthusiasm for crusading, and responded to an appeal for naval help by sending a massive fleet to the Holy Land. In 1123, off Ascalon, much of the Fatimid navy was sent to the bottom of the sea.18 This enabled the Venetians to blockade Tyre, which was still in Muslim hands but fell the next year. Here the Venetians established themselves in a highly privileged position, acquiring not merely one-third of the town but estates outside it, and the right to a church, a square, an oven and a street in every town they helped capture in future. They were to be exempt from all trade taxes; it was proclaimed that ‘in every land of the king or his barons, each Venetian is to be as free as within Venice itself’.19 Tyre became their major base along the Syro-Palestinian coast. This did not prevent occasional razzias by the Fatimid fleet, but the Egyptian navy now found that it had no bases where it could call in for supplies. On one occasion some Egyptian sailors who tried to land in the hope of taking on water were chased away by loyal bowmen of the Latin kingdom.20 The Fatimids lost access to the forests of Lebanon, for millennia a vital resource of Levantine shipbuilders. Although the sea battle at Ascalon did not mark the destruction of the entire Fatimid navy, it did mark a turning-point: Muslim shipping was no longer able to challenge the supremacy of Christian fleets. Command of the eastern Mediterranean sea-lanes had fallen into the hands of the Pisans, Genoese and Venetians. Participation in the early crusades had brought these cities not just quarters in the cities of the Holy Land but domination over movement across vast swathes of the Mediterranean.

Finally, even the Byzantine emperor realized that he could not stand in the way of the Venetians. He reluctantly confirmed their privileges in 1126.21 The Venetian presence stimulated the Byzantine economy.22 Even if the Venetians paid no taxes to the imperial fisc, the Byzantine subjects with whom they conducted business did so, and in the long term revenue from commercial taxation rose rather than fell. But the emperors could not always see beyond their immediate fiscal concerns. The existence of a highly privileged group who paid no taxes aroused xenophobia.23 In the 1140s Emperor Manuel I Komnenos renewed the attack on the Venetians, adopting different tactics: he noticed that the Italians had flooded into Constantinople, some becoming denizens of the city and integrating themselves into city life (the bourgesioi, or bourgeois), while others, who were more troublesome, had come mainly to trade overseas. He created an enclosed area next to the Golden Horn, taking away land from German and French merchants, so as to create a Venetian quarter and control the Venetian traders more easily.

The rise of the north Italians led to the eclipse of other groups of merchants who had successfully conducted business in the eleventh-century Mediterranean: the Amalfitans and the Genizah merchants. Amalfi lost favour at the Byzantine court, and its citizens based in Constantinople were even made to pay taxes to the Venetians. One obvious reason was that Amalfi could not supply what Venice offered: a large fleet able to defeat the navy of Robert Guiscard. Although Amalfi managed to remain largely independent of Norman rule until 1131, its status in Byzantine eyes was gravely compromised by its location so very close to the strongholds of the Norman conquerors of southern Italy – Salerno lies a short boat-ride away.24 But Amalfi still counted. In 1127 Amalfi and Pisa entered into a treaty of friendship. But in 1135 the Pisans joined a German invasion of the newly established Norman kingdom in southern Italy and Sicily. Roger of Sicily permitted Amalfitan ships to leave port and attack any enemy vessels they could find – no doubt his new subjects dreamed of finding stray Pisan merchantmen piled high with expensive goods. While the Amalfitans were away, the Pisan navy entered the harbour of Amalfi and sacked the city, carrying away a great booty; they attacked again in 1137.25 Amalfi’s maritime trade contracted into the waters of the Tyrrhenian Sea, including Palermo, Messina and Sardinia, while its landward trade in southern Italy developed healthily, so that very many inland towns, such as Benevento, came to possess little nuclei of Amalfitans.26 By 1400 Amalfi had become a source of unexciting but basic goods such as wine, oil, lard, wool and linen cloth, though it also became known for its fine paper.27 Underneath these changes, there existed a striking continuity. The Amalfitans had always understood that the sea was not their only source of a livelihood. They continued to cultivate vines on the steep hillsides of the Sorrento peninsula, and did not simply see themselves as professional merchants.28

Wider changes that were affecting the Mediterranean in the twelfth century left Amalfi on the margins; it stood too far from the new centres of business in northern Italy and across the Alps. The Genoese, Pisans and Venetians could gain easy enough access to France and Germany, not to mention the Lombard plain, and were able to forge links with the great cloth cities far away in Flanders, so that selling fine Flemish woollen cloth to purchasers in Egypt became a regular source of profit to the Genoese. Amalfi represented an older order of pedlar trade, in which small numbers of merchants carried limited quantities of expensively priced luxury goods from the centres of high civilization in the Islamic world and in Byzantium to equally small numbers of wealthy princes and prelates in western Europe. Henceforth, the elite of Amalfi, Ravello and neighbouring towns used the knowledge of record-keeping and accounting passed down by their forebears to enter the civil service of the kingdom of Sicily, where several followed very successful careers. This elite did not lose its taste for eastern motifs. The Rufolo family of Ravello built a palace in the thirteenth century which borrowed from Islamic architectural styles, and the cathedral of Amalfi, with its famous ‘Cloister of Paradise’, recalls elements of both Islamic and Byzantine style.29 The decision to borrow eastern motifs did not indicate particular openness to other religions and cultures. As in Venice, exotic styles proclaimed wealth, prestige and family pride, as well as nostalgia for the days when Amalfi (with Venice) dominated communications between East and West.

The same period saw the eclipse of another group of traders and travellers, the Genizah merchants. Around 1150 the stream of merchant letters deposited in the Cairo Genizah began to dry up;30 after 1200, non-Egyptian matters largely disappeared from it. That vast world, stretching from al-Andalus to Yemen and India, had now contracted to the Nile Valley and Delta. Political calamities included the rise of the Almohad sect in Morocco and Spain, which was intolerant of Judaism; among the Jewish refugees from the Almohad West was the philosopher and physician Moses Maimonides.31 Yet the greatest difficulty faced by the Genizah merchants was the rise of the Italians. Venice and Genoa discouraged Jewish settlement – according to a Spanish Jewish traveller, there were only two Jews in Genoa around 1160, who had migrated from Ceuta in Morocco.32 As the Italians gained greater control over communications across the Mediterranean, and as Muslim merchant shipping became more than ever exposed to Christian attack, the old sea routes became less attractive to the Genizah merchants. And, as Italian naval power grew, even the sea routes between Byzantium and Egypt, along which the Genizah Jews had travelled in the past, fell into the hands of Italian shipowners, who benefited from grants of privilege by both the Byzantine emperors and the Fatimid caliphs.

There was another important reason why the Jewish merchants lost influence. In the late twelfth century a consortium of Muslim merchants known as the Karimis emerged and took command of the routes running down the Red Sea towards Yemen and India, along which the Jews had been extremely active in the previous two centuries. These routes fed into the Mediterranean: eastern spices and perfumes arrived at Aydhab on the Red Sea coast of Egypt, were transported overland to Cairo, and then by water up the Nile to Alexandria. Following attempts in the 1180s by a maverick crusader lord, Reynaud de Châtillon, to launch a fleet in the Red Sea (in the hope of raiding Madina and Mecca), the Red Sea was closed to non-Muslim travellers. The Karimis continued to dominate business there until the early fifteenth century.33 A grand partnership, mediated by the rulers of Egypt, joined the Italians and the Karimis and ensured the regular flow of pepper and other spices into the Mediterranean. Trading networks that had carried a single individual all the way from southern Spain to India were now fragmented in two: the Mediterranean sector was Christian, the Indian Ocean sector was Muslim.

The Fatimid rulers and their successors, the Ayyubids (of whom the most famous was the Kurdish warlord Saladin), became increasingly interested in the revenues they could raise from trade. This was not out of a mercantilist spirit, but because they saw the spice trade, in particular, as a source of funds to cover their war expenses. During twelve months in 1191–2 the so-called one-fifth tax (khums) raised 28,613 gold dinars from Christian merchants trading through the Nile ports. This means that exports through these ports reached well over 100,000 dinars even at a difficult time – Saladin had captured Jerusalem, the Third Crusade was under way and the Italian cities, as well as southern French and Catalan towns, were sending fleets to the Holy Land.34 Despite the name of the tax, it was levied at a higher rate than one-fifth on spices such as caraway, cumin and coriander, for the Egyptian government was well aware how keen the western Europeans were to acquire these products. In the late twelfth century, an Arab customs official, al-Makhzumi, compiled a handbook on taxation in which he listed the goods that passed through Egyptian ports. He mentions a much wider range of products than the Genizah letters reveal: Damietta exported chickens, grain and alum, the last of which was a government monopoly in Egypt. Alum was required in increasing quantities by European textile producers, who used this dull grey powder as a fixative and cleansing agent.35 Egypt was also a source of flax, heavily taxed by the government; emeralds, over which the government took increasing control; gold, looted from the tombs of the Pharaohs; and a much-prized drug, known in the West as mommia – powdered mummy. The Nile Delta ports received timber, which was in very short supply within Egypt; Alexandria acquired iron, coral, oil and saffron, all carried eastwards by Italian merchants.36 Some of these commodities could be classified as war materials, and the papal court was becoming increasingly worried at the role of the north Italian fleets in supplying armaments to the Muslims while acting, or posing, as the main naval defence force of the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem. Arabic writers refer to a type of shield known as the janawiyah, that is, ‘Genoa’, suggesting that some at least of these shields were brought illicitly from Italy.37

Occasionally tensions boiled over and Italian merchants were arrested, but the Fatimids and Ayyubids could not risk undermining their finances. On one occasion, Pisan sailors attacked Muslim passengers on board a Pisan ship; they killed the men and enslaved the women and children, as well as stealing all the merchandise. In reprisal, the Egyptian government imprisoned the Pisan merchants who were in Egypt. Soon after, in 1154–5, the Pisans sent an ambassador to Fatimid Egypt. Relations were mended and a promise of safe-conduct for merchants was obtained.38 The Pisans were not alone in preferring Egypt to the Holy Land. Out of nearly 400 Venetian trade contracts that have survived from before 1171, it is no surprise that over half concern trade in Constantinople, but seventy-one concern Egypt, rather more than concern trade with the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem.39 These are only accidental survivals from a mass of documents mostly now lost, but they suggest how strong was the lure of the East.

North-west Africa also lured Italian merchants when access to Constantinople, Alexandria, Acre or Palermo was obstructed by quarrels with their rulers. The Pisans and Genoese visited the ports of the Maghrib to acquire leather, wool, fine ceramics and, from Morocco, increasing quantities of grain. Particularly important was the supply of gold, in the form of gold dust, that reached the towns of the Maghrib along the caravan routes that stretched across the Sahara.40 In the middle of the twelfth century these lands fell under the rule of the uncompromising Almohad sect of Islam. Almohad Islam had its own Berber caliph, and was viewed by Sunni Muslims (such as the Almoravids they largely replaced) as rank heresy. Its principal feature was an attempt to return to what was seen as a pure and unadulterated Islam, whose fundamental principle was the absolute Oneness of God – even to name his attributes, such as mercy, was to misunderstand God’s true being. Although hostile to their Jewish and Christian minorities, the Almohad caliphs in Spain and North Africa welcomed foreign merchants, whom they saw as a source of income. In 1161 the Genoese sent an embassy to the Almohad caliph in Morocco; a fifteen-year peace was agreed, and the Genoese were assured that they could travel throughout the Almohad territories with their goods, free of molestation. In 1182 Ceuta took 29 per cent of recorded Genoese trade, a little ahead of Norman Sicily, but, if one includes Bougie and Tunis, North Africa dominated the trade of Genoa, with nearly 37 per cent.41

The Genoese acquired a fonduk – a warehouse and headquarters with living quarters – in Tunis, Bougie, Mahdia and other cities along the coast of North Africa. The remaining fonduk buildings in Tunis are of the seventeenth century and belonged to the Italian, German, Austrian and French merchants.42 The fonduks of the Italians and Catalans could expand into a whole merchant quarter. The acts of the Genoese notary Pietro Battifoglio, of 1289, portray a large and vibrant Genoese community in Tunis, consisting of merchants, soldiers, priests and fallen women, who took great pride in their tavern filled with wine casks, from which even the Almohad ruler was happy to draw taxes.

Using the trade contracts, the life and career of several successful Genoese and Venetian merchants can be reconstructed. At the top of the social ladder stood the great patrician families such as the della Volta of Genoa, whose members often held office as consul, and who directed the foreign policy of the republic – whether to make peace or war with Norman Sicily, Byzantium, the Muslims of Spain, and so on. Since they were also active investors in overseas trade, they operated at a great advantage, able to negotiate political treaties that brought commercial dividends they were keen to exploit.43 The great Genoese families were grouped together in tight clans, and the common interest of the clan overrode the immediate interest of the individual.44 The price that Genoa paid was acute factional strife, as rival clans tried to gain mastery of the consulate and other offices. At the other extreme the Venetian patriciate generally managed to keep strife in check, by accepting the authority of the doge as first among equals; once again great families such as the Ziani, Tiepolo and Dandolo dominated both high office and trade to the really profitable destinations, such as Constantinople and Alexandria. Their success had a knock-on effect on the fortunes of an urban upper middle class that included many very successful merchants. Not just ancestry differentiated the great patrician houses from the plebeian merchants; the patricians could also call on much more diverse assets, so that if trade dried up during a period of warfare they still had revenues from urban and rural property or tax farms. Their position was less fragile than that of the ordinary merchants; they had greater staying-power. So, while the commercial revolution made many fortunes, it also further enriched the elite and strengthened rather than weakened their commanding position in the great maritime cities of twelfth-century Italy.

Two ‘new men’ are well documented. Romano Mairano, from Venice, started in a small way during the 1140s with trading expeditions into Greece, operating mainly from the Venetian colony in Constantinople.45 He then turned to more ambitious destinations, including Alexandria and the Holy Land. His career illustrates how the Venetians had taken charge of the sea routes linking Byzantium to the Islamic lands. They were well ensconced in internal Byzantine trade too, maintaining contact between Constantinople and the lesser Greek cities.46 By 1158 Romano prospered greatly, supplying 50,000 pounds of iron to the Knights Templars in the Holy Land. He was not simply a merchant; he became a prominent shipowner. His star still seemed to be rising when the Byzantine emperor turned against the Venetians, whom Manuel I suspected of showing sympathy for his foe the king of Sicily, and who were, in any case, increasingly the focus of Greek resentment at the powerful position they occupied (or were imagined to occupy) in the Byzantine economy. Aware of this trend, Mairano began to build up his business in Venice during the late 1160s. After his first wife died, he remarried and found himself richer thanks to his new wife’s fat dowry. Working with Sebastiano Ziani, a future doge, he built the largest ship in the Venetian merchant fleet, the Totus Mundus or (in Greek) the Kosmos, which he sailed to Constantinople. Relations with the emperor seemed to be improving, and Manuel I even issued a decree in which he declared he would hang anyone who molested the Venetians. But his aim was to create a false sense of security, and in March 1171 the emperor unleashed a Kristallnacht against the Venetians, knowing he could count on public support. Thousands of Venetians were arrested within the confines of their quarter, hundreds were killed and their property was seized. Those who could escaped to the wharves, where the Kosmos stood ready to sail, protected against flaming arrows and catapult stones by a covering of animal hides soaked in vinegar. The Kosmos managed to reach Acre, carrying news of the disaster, but Romano Mairano had lost all his other assets, and was probably deeply in debt after building his great ship. Two years later his vessel reappeared off Ancona, which had proclaimed its allegiance to Manuel Komnenos and was under siege from Manuel’s rival, the German emperor Frederick Barbarossa. Not surprisingly the Venetians now preferred Barbarossa to Manuel, quite apart from their concern that Ancona was becoming a commercial rival within the Adriatic. They obligingly helped bombard Ancona, though the city held out against the Germans.47

By now, Mairano was about fifty years old, and had to rebuild his business from scratch. He could only do this by turning once again to the patrician Ziani family; the late doge’s son Pietro invested £1,000 of Venetian money in a voyage Romano was to make to Alexandria. Romano carried with him a large cargo of timber, paying no attention to papal condemnation of the trade in war materials. While relations between Venice and Constantinople were so bad, he sent ships to North Africa, Egypt and the kingdom of Jerusalem, trading in pepper and alum. He was ready to return to Constantinople when a new emperor readmitted the Venetians on excellent terms in 1187–9. Even in old age Romano continued to invest in trade with Egypt and Apulia, though funds ran low again in 1201, when he borrowed money from his cousin; he died not long after.48 It was, then, a career marked by ups and downs, as notable for its successes as for the disastrous collapse of his business and his dramatic escape in mid-career.

Another uneven career was that of Solomon of Salerno. Though he came from southern Italy he traded from Genoa, where, like Mairano, he was close to the patrician families.49 He also had personal ties to the king of Sicily, whose faithful subject, or fidelis, he was said to be. He showed he wanted to be counted as Genoese when he bought some land just outside the city, and he tried to forge a marriage alliance between his daughter and one of the patrician families; he had turned his back on Salerno. He recognized that Salerno, Amalfi and neighbouring towns had been greatly overtaken by the more aggressive trading cities of Genoa, Pisa and Venice, and it was in Genoa that he made his fortune. He brought with him from Salerno his wife Eliadar, who was another keen merchant, for there was nothing to prevent women in Genoa from investing money in trading ventures. Solomon and Eliadar made a formidable pair, casting their eyes over the entire Mediterranean. Like Romano Mairano, Solomon was willing to travel to its furthest corners in pursuit of wealth. Golden opportunities beckoned in 1156, in Egypt, Sicily and the West. In summer of that year he decided to capitalize on the more open mood of the Fatimids. He agreed to travel out to Alexandria on behalf of a team of investors, and then to follow the Nile down to Cairo, where he would purchase oriental spices including lac, a resin that could be used as a varnish or dyestuff, and brazilwood, the source of a red dye. Solomon also had plenty of interests that pulled him in other directions. The same year he was trying to recover 2⅔ pounds of Sicilian gold coinage, a formidable sum at the time, from a Genoese who had absconded with the money in Sicily while Genoese ambassadors were negotiating a treaty with its king.50 He was away nearly two years in the East, leaving Eliadar at home to manage a triangular trade network linking Genoa, Fréjus and Palermo.

After his return from the East, Solomon looked westwards, trading with Majorca and Spain as well as Sicily and his old favourite, Egypt, where he invested very substantial amounts of money. One document describes a roundabout voyage he commissioned that was typical of the more ambitious ventures of the time: ‘to Spain, then to Sicily or Provence or Genoa, from Provence to Genoa or Sicily, or if he wishes from Sicily to Romania [the Byzantine Empire] and then to Genoa, or from Sicily to Genoa’.51 Great Genoese patricians eagerly invested money in Solomon’s expedition to Egypt, ignoring a clause in the documents that implied the ship might be sold in Egypt. For not merely did the Italians send timber to the shipyards of Alexandria, they sent whole ships, ready for use in the Fatimid fleet. Solomon was at the peak of his success; although he was an outsider, his daughter Alda was betrothed to the son of a powerful member of the Mallone clan. Solomon had his own notary to record his business, and documents grandly speak of the ‘court of Solomon’, suggesting that he lived in a lavish style. Like Romano Mairano, however, he lay at the mercy of political changes over which he had no control. Having made friends with the king of Sicily in 1156, Genoa was forced in 1162 to abandon what had been a very lucrative alliance that gave access to vast amounts of wheat and cotton; the German emperor Frederick Barbarossa was breathing down the necks of the Genoese, and they felt obliged to join his army of invasion directed against Sicily. Ansaldo Mallone broke off the advantageous engagement between his son and Solomon’s daughter. Suddenly the business empire of Solomon and Eliadar seemed very fragile.

However, some contact with Sicily was still possible. In September 1162, a few months after the Genoese abandoned Sicily for Germany, Solomon received the emissaries of an eminent Sicilian Muslim, ibn Hammud, the leader of the Muslim community in Sicily, who advanced him funds against the security of an ermine mantle, silver cups and other fine goods. A Sicilian Arab writer eloquently said of ibn Hammud: ‘he does not suffer his coin to rust’. He was very wealthy: taking advantage of accusations that he was disloyal, the king of Sicily fined him 250 pounds of gold, an enormous fortune.52 Contacts such as these enabled Solomon to stay in business, but conditions were bleak for someone with his interests and expertise. Quarrels between Genoa and the king of Jerusalem inhibited trade to the Holy Land, and access to the eastern Mediterranean was rendered more difficult by the breach with the king of Sicily, whose fleets controlled the passages between the western and the eastern Mediterranean. Like other Genoese merchants, Solomon and his wife now turned from the eastern to the western Mediterranean, trading with the important port of Bougie in what is now Algeria. Solomon must have died some time around 1170. His ambition of anchoring himself to the Genoese patriciate by a marriage alliance had been frustrated by political events. Until he and his heirs entered the ranks of the patriciate, his position would always be fragile. The land he acquired outside Genoa was worth only £108 of Genoese silver, and his wealth was mainly built on cash, loans, investments and speculations, whereas the wealth of the city aristocracy was firmly rooted in urban and rural property. It was this that gave them the staying-power that men such as Solomon of Salerno and Romano Mairano lacked. And yet it was by working together that the patricians and the merchants created the commercial revolution that was taking place.