4

CONTEMPORARY AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

The Illustrator as Scientist and Cultural Historian

The Illustrator as Journalist and Commentator

Professional Practice

The parameters of Illustration practice have changed. As well as the ‘ebb and flow’ of what is actually meant by illustration , its actual realm of operation has become ‘porous,’ with disciplines once thought of as professionally linked now overlapping and in some instances deeply intertwined. This has a significant bearing on the concept of professional practice for the illustrator , not only for the here and now but for the future.

Broadly speaking, most illustration is commissioned by or generated for the creative, media and communications industry. This generic title represents a vast economic powerhouse whose reach and influence is prevalent throughout the world via the internet, broadcasting, publishing, advertising and entertainment. There is now a rapidly changing, complex and accelerating media where the ability to communicate creatively, meaningfully and effectively for a global audience is key. The ever changing circumstances of modishness, customs and behaviour; the economy; and technological advancements have instigated a need in many audiences around the world for imagery that satisfies a thirst for new knowledge and new markets. This alters perceptions held regarding established and ‘discrete’ disciplines: illustration, graphic design, photography, animation and film – a typical list with practitioners often declaring ownership of and identification with just one of those disciplines. That is now considered a hackneyed perception; there are alternative, ‘all encompassing’ roles being declared such as ‘creative’ (working within the broad realm of media, design and communication) a supposition that is becoming the norm. But what is meant by a ‘creative,’ and what defines such a role?

INTERDISCIPLINARY PRACTICE

A creative practitioner can be considered someone who has the intellectual, creative, managerial and technical skills to cut across a range of disciplines and perform largely unsupervised. It will command abilities for the following:

• Research

• Effective communication: having the personal confidence to engage in social and professional interaction; presentation; writing

• Innovation, problem solving and ideas generation

• Aesthetic discernment: having a complete and objective appreciation and working knowledge of most visual languages and subjects

• Organizational and collaborative skills

• Media application and technical production

Once largely regarded as transferrable, and in some instances, more ‘advanced’ or superincumbent, these attributes are essential for illustration professional practice as more and more opportunities for talented communicators are identified within publishing houses, the media, advertising agencies, design groups and consultancies, television, film and online broadcasting, entertainment, game design, music and performance. Acquiring these specific skills and by integrating other appropriate interests into one’s portfolio can determine far-reaching opportunities:

• Authorship

• Copywriting

• Journalism

• Academia and research

• Subject specialism such as history or science

• Entertainment and performance

• Broadcast

• Art direction or editorship

• Design and making, such as artefacts and products

Frequently, illustrators will develop their own unique combinations of vocations, creating disparate and original stances and operations. It is possible to affix any of the aforementioned disciplines to a practitioner’s job description such as: author-illustrator, journalist-illustrator, scientist-illustrator and musician-illustrator.

A typical example of where illustrators broaden their scope is seen frequently in publishing. It is known for certain individuals to conceive, research, graphically design, art direct, illustrate and technically engineer complex interactive books and other products. The individuals in question will have creative ownership of the entire publication. There is an enormous diversity of opportunity in the world of creative communication, and these criteria are prerequisite for successful professional practice.

4.1

Philip Burke’s

caricature of the singer Courtney Love, commissioned by Rolling Stone

magazine, represents a genre of illustration that is widely acknowledged as one of the discipline’s cornerstones of commercial practice – ubiquitously usable and immensely popular. However, does it represent multi-disciplinary practice? Not a relevant question for Philip Burke, a highly successful and sought-after professional, to answer. But, the majority seeking a career within the broadening framework of illustration practice will have to promote their wider abilities: intellectual, creative, problem solving, organizational, team working, operative and technical skills.

4.2

A hypothetical taxonomy of various career opportunities through illustration.

The Polymath Principle

This is a provocative thesis that advocates a need for illustrators and other creative practitioners to acquire a greater knowledge base through focused scholarship and an increase in intellectual capacity. This paragraph from Illustration: Meeting the Brief (Bloomsbury, 2014) by the author sums up the concept: ‘We are beginning to see a return of The Polymath Principle, in other words an illustration practice that exudes authority and a breadth of intellectual skills and learning. The consequence is that many illustrators will have wide-ranging and in-depth knowledge of subject matter and acquire an esteem-driven ownership for their work. Examples might be new or original knowledge embedded in their illustrations, literary authorship for fiction, documentation, journalism and commentary.’

The implication for this will be insurmountable for some practitioners and students of visual communication; it clearly transcends the traditional concept of the commercial illustrator being chosen for his or her style in order to undertake a prescribed and heavily directed brief. Clients, audiences and media platforms will expect practitioners to have an individual, critical voice with an expectation to be challenging and sometimes provocative; to be able to use their knowledge base to take ideas and move into new and exciting realms; and, where appropriate, confront and contradict the wider communications world.

The illustrator of today and the future will need to see how global, experiential and experimental insights can generate the most felicitous models for contemporary communications problems; to stretch and question one’s practice and gain inspiration from within and beyond immediate boundaries; be professionally and intellectually adept at social engagement; and use human interactions to inspire new thinking and, when situations are conducive or favourable, create polar tensions or friction to inspire fresh and original thinking. The communicator will be expected to produce work where success is determined by substantive impact: through context, reach and significance by creating new forms of creative expression; by preserving, conserving and presenting cultural heritage; influencing the design, delivery of curricula and syllabi in education and knowledge exchange; and by contributing to economic and cultural prosperity.

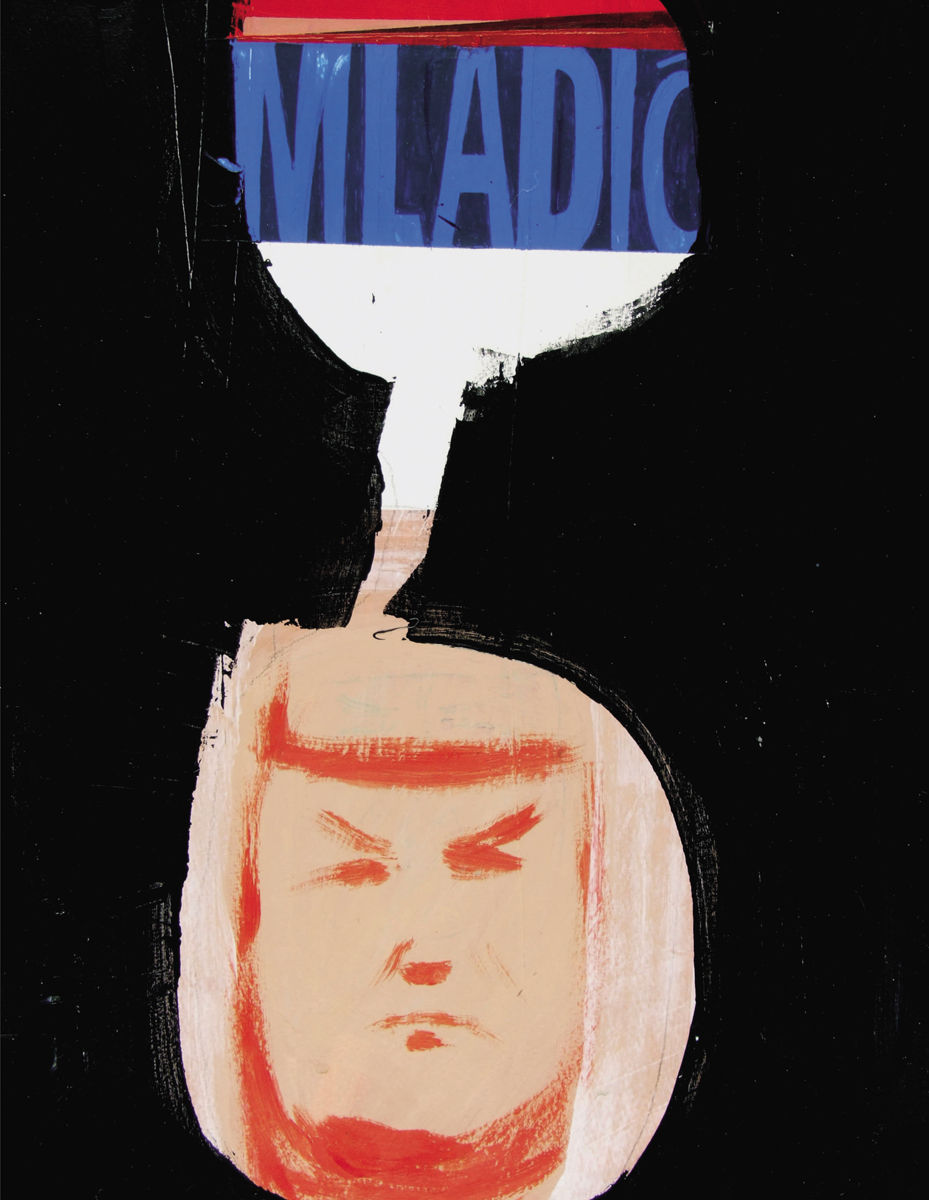

4.3

The world of literature and fiction offers the illustrator significant opportunity for authorship and original thinking: Children’s picture book publishing will facilitate opportunities for the author–illustrator to acquire complete ownership of the creative work undertaken. This is the book cover of a product conceived, designed, written and illustrated by Emma Yarlett

.

‘‘THE BEST ART AND DESIGN UNDERGRADUATE EDUCATION ENCOURAGES THE ACQUISITION OF APPROPRIATE TRANSFERABLE SKILLS THAT ARE NOT ONLY PRACTICAL, BUT INTELLECTUAL AND KNOWLEDGE BASED: THE COMMAND OF WRITTEN AND ORAL LANGUAGE, PRESENTATION AND RESEARCH.’’

THE ILLUSTRATOR AS SCIENTIST AND CULTURAL HISTORIAN

The notion of an illustrator assuming the professional status of scientist or cultural historian is not new. An example as shown by retail publishing is that there is an increase in the numbers of non-fiction children’s books being authored and illustrated by the same individual. Why? What gives illustrators the right to hold such ‘upstart’ positions of importance and authority?

The status of the commercial art practitioner has increased in recent years with seemingly more responsibility for context and content. The graduate graphic designer will often be appointed as an art director soon after leaving higher education, whilst in times past it would have taken years of apprenticeship and gradual ascents in the promotional process. This may be a result of ‘sea changes’ in recent and current art and design undergraduate education. The reduction of an overtly vocational emphasis with subjects such as studio-based illustration practice now integrated with professional practice studies and contextual, historical and cultural studies has facilitated an educational experience enabling graduates to multitask, to be professionally independent and to be much more intellectually capable. The best art and design undergraduate education encourages the acquisition of appropriate transferable skills that are not only practical, but intellectual and knowledge based: the command of written and oral language, presentation and research.

Professional and student illustrators undertaking research, commissioned and/or given project work will often be required to engage with specialist subject matter. This can lead the illustrator to assume a position of authority in his or her thematic domain of operation. Continuous professional involvement with the topic, along with researching and illustrating books and other material at a national and international level, would soon qualify the illustrator as an ‘expert,’ even without a formal qualification in the subject. Opportunities to undertake focused postgraduate master’s degrees and research higher degrees can also facilitate and expand an illustrator’s authorial status.

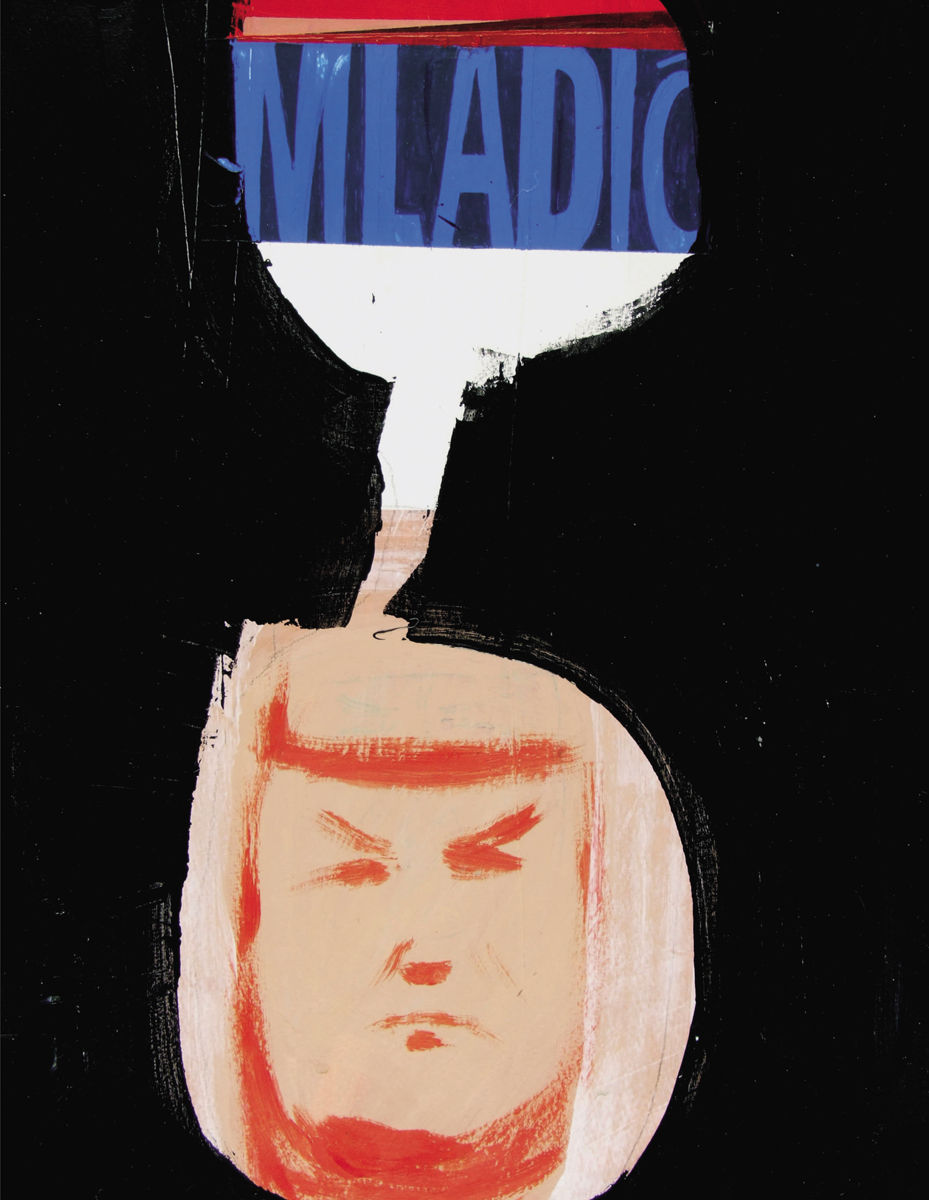

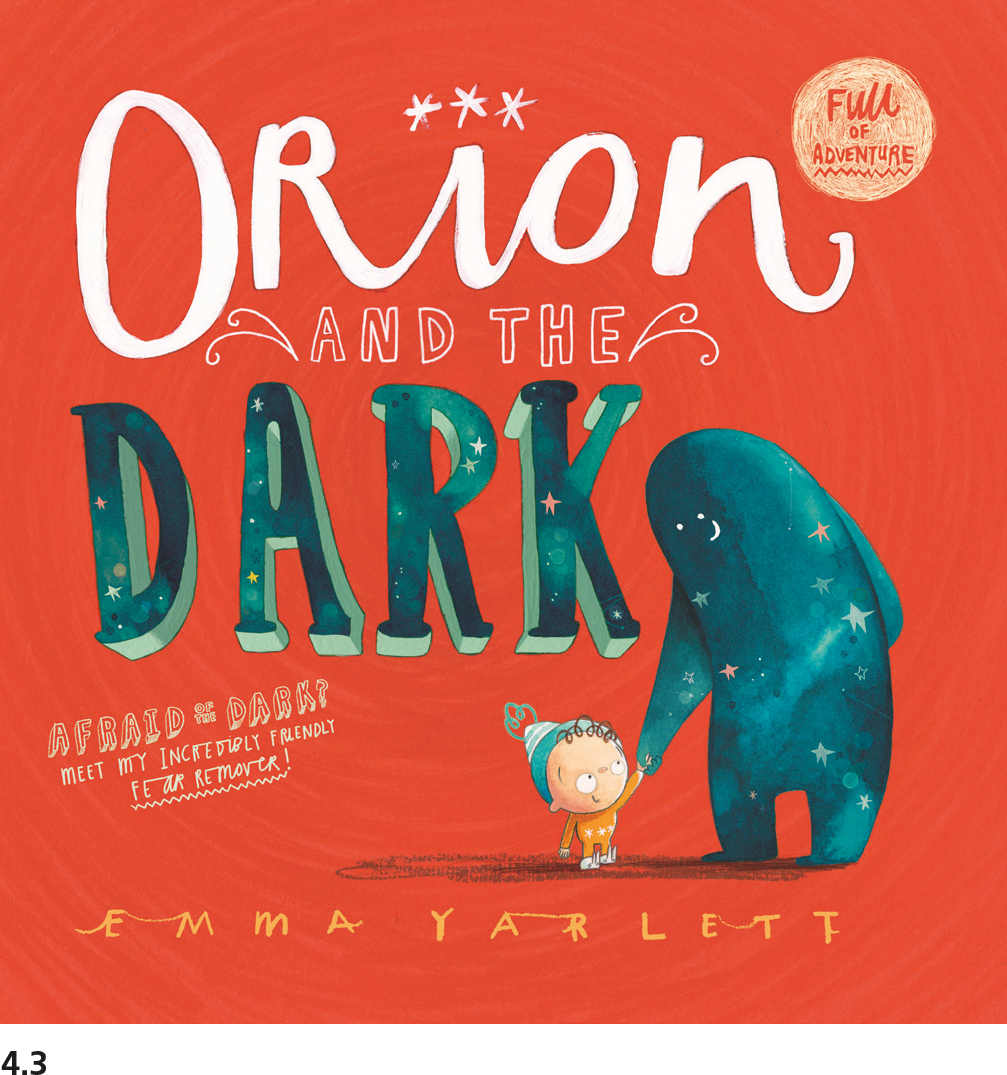

4.4a–4.4b

Paul Bowman

combines illustration and an in-depth knowledge of contemporary history to convey comment regarding the Srebrenica atrocities during the Balkan conflict.

There are a number of scientific and cultural illustrators who trained specifically in subject matter: archaeology, botany, biology, zoology. These individuals have established their status of author–illustrator by approaching their education and training the ‘other way round’ by undertaking undergraduate science and cultural studies degrees first. In order to elucidate and ‘illustrate’ academic, practical or research work, certain individuals employ an inherent ‘artistic gift’ and thus begin to draw and visualize, initially as an memory aide to their studies and then with later work manifesting as published texts with illustrations. All of this is exemplified by the roster of membership of the Guild of Natural Science Illustrators, a professional society with significant international standing. The intrinsic link between words and image and the increase in illustrators engaging directly with subject matter suggests the firm establishment of a culture representative of and given for the non-fiction author–illustrator.

Two examples of ‘polymath-type’ practices that are authorial, original, knowledge bearing and natural science themed:

4.5–4.12

Katrina Van Grouw

is an illustrator–artist, author, researcher, naturalist, ornithologist, taxidermist and curator. These drawings are part of a collection of over 300 images created from actual specimens and representing 200 avian species brought to life and published in Van Grouw’s book The Unfeathered Bird

(Princeton University Press, 2012). It is the most richly illustrated book on bird anatomy ever produced. The work represents extensive observation, research and sustained detail regarding the efficacy of the drawings, and it exemplifies a practice bridging visual art and illustration with science; it is a typical example of research through analytical drawing. Van Grouw is a recognized expert on this subject matter and, as such, makes the project truly ‘polymath-ic’. The species shown are Budgerigar (with mirror), Fish Owl, Great Horntail, Pouters, Robin (on spade), Woodpecker feet, Ostrich feet and a pairing of Frigate Bird with Tropic Bird.

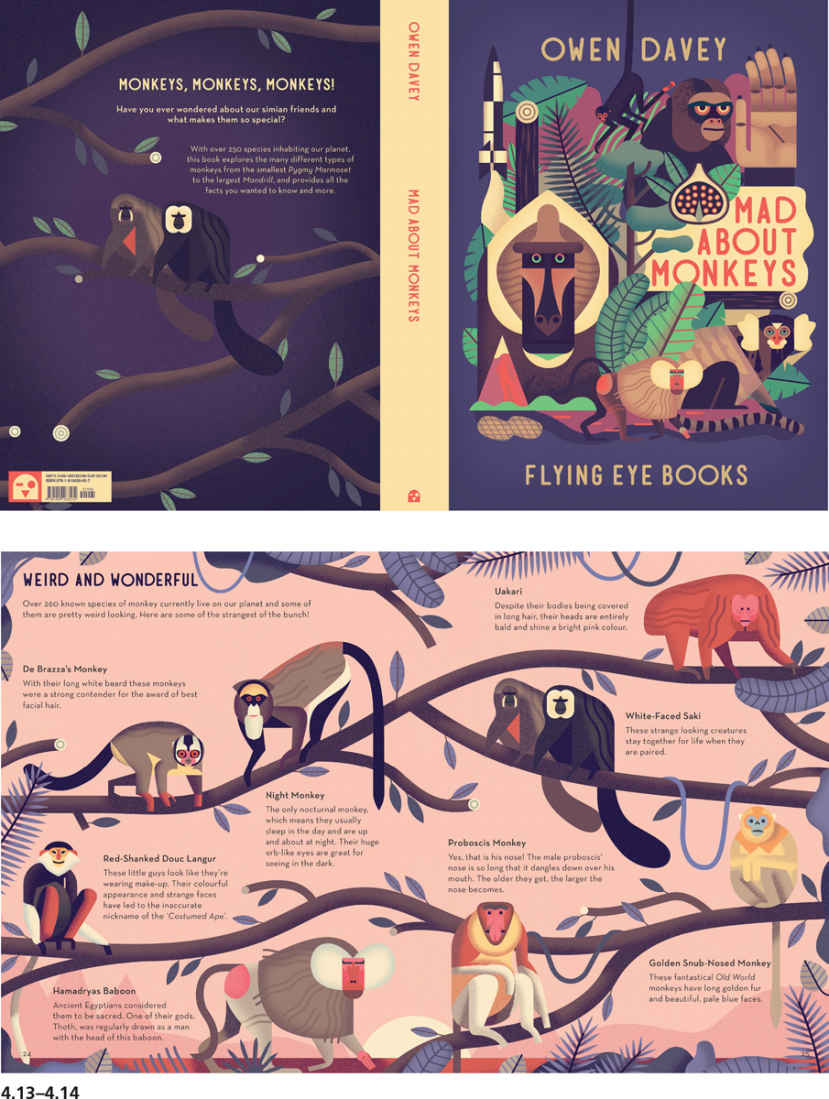

4.13–4.14

Owen Davey

has conceived, researched, written, designed and illustrated Mad About Monkeys

(Flying Eye Books). The project is commercial in nature and aimed specifically at a young audience. The product makes no pretence regarding its contextualized remit and rests comfortably within the knowledge-bearing realm of children’s non-fiction. The content is educational, yet fun and entertaining. Davey has challenged the accepted norm of producing illustrations of nature in a purely representative manner by not adhering to the ‘tenets’ of morphological accuracy.

ILLUS TRATOR AS JOURNALIST AND COMMENTATOR

Journalists write or broadcast reports and present commentary. Their field of operation is great and covers much from current affairs to specialist concerns. Can the work of certain illustrators be considered as journalism? Some illustration can certainly be considered as journalistic. Many illustrators attain specialist status with regard to subject matter, and this can cross the divide of editorial practice. When producing an image in conjunction with a journalist writer, the illustrator has not only the creative freedom to determine its essence but also knowledge and insight into the subject. Combined, the text and illustration presents opinion and account. In this context, the illustration is ‘journalistic’ in its nature.

But how can an illustrator replicate the work of a journalist? Many illustrators write professionally, both fiction and non-fiction material. However, in a contextual sense, these examples fall into different domains of practice.

Can illustration itself manifest as journalism? Photojournalism certainly does. If photographic imagery can be evidenced as a form of journalistic practice, why not illustration? The art of drawing on location, visual note taking, is sometimes used as an alternative to photography, usually when the use of cameras is prohibited. Courtroom scenes are often recorded by an attendant illustrator, the imagery broadcast or published in newspapers. There is another field of practice whereby actual artwork is being commissioned: war artist–illustrators have been dispatched to areas of conflict to capture atmosphere and detail related to aspects of the unfolding history. Recent examples include the Falklands and the Balkans. In itself, this might be considered as adjacent to actual journalism as one could get. By their very nature and physical presence, the war drawings provide a ‘hands-on’ real-life experiential account of the dramatic events that they have recorded.

The term given for this method of practice is reportage: the illustrator working on location and visually recording appropriate aspects of the subjects covered. The illustrator David Gentleman is renowned for his reportage drawings and illustration normally produced on location in countries such as India; his books provide fascinating cultural insights and information.

Magazines and newspapers sometimes use reportage illustration for features about travel. The accent is on a ‘rough guide’ approach, providing visual commentary that tends to be ‘warts and all’.

The illustrator can operate as a journalist. But one must transcend the role of being solely a visualizer and recorder of observed material. There needs to be a holistic approach that engenders status regarding one’s authority and credibility with subject matter and working practice. It must also be said that the craft of writing is an essential component of the professional make-up of the journalist–illustrator. The boundaries of the media and creative disciplines are blurred. The essence and contextual thrust of writing and illustration is communication. Journalism with illustration is another example where this can be evidenced.

‘‘REPORTAGE: THE ILLUSTRATOR WORKING ON LOCATION AND VISUALLY RECORDING APPROPRIATE ASPECTS OF THE SUBJECTS COVERED.’’

4.15

Anna Bhushan’s

uncompromising and authoritative illustration for The New York Times

is distinctly journalistic: it aims to elucidate a statistic given by the article it accompanies that female Chechen suicide–attackers, in general, kill an average of 21 people per attack compared to 13 for males. The article was entitled ‘What Makes Chechen Women So Dangerous?’.

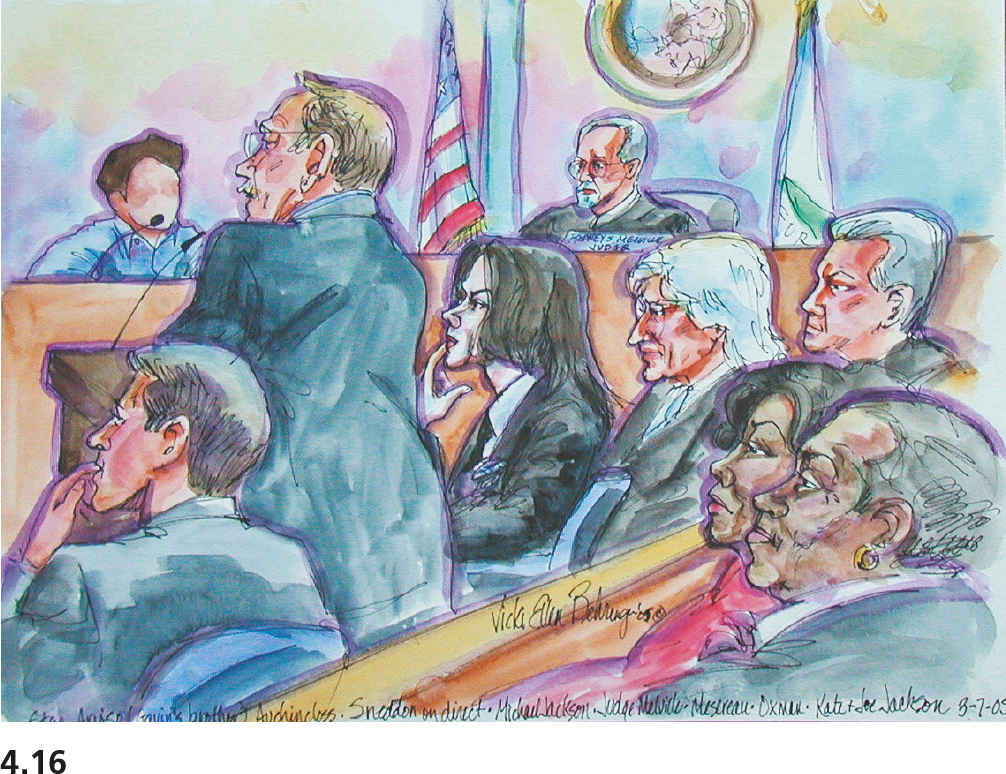

4.16

Vicki Behringer

depicts the unfolding drama of the Michael Jackson trial by drawing directly from inside the courtroom. It is a meaningful and high-profile example of reportage illustration.

4.17

A World Illustration Award Winner 2015, Olivier Kugler

is a true visual-reportage journalist. This image is part of a series, originally commissioned by Medecins San Frontieres, and was researched and recorded on location in the Middle East. The drawings, along with the hand written annotations, convey firsthand, harrowing narratives related the experiences of Syrian refugees eking out an existence in Iraqi Kurdistan.

THE ILLUSTRATOR AS AUTHOR OF FICTION

Narrative fiction is undoubtedly the contextual domain of practice that offers illustrators the most significant opportunities for authorship. Approximately 50 per cent of young audience fiction is written and illustrated by the same individual. The graphic novel and other sequential forms provide further opportunities. The suggestion here is that one assumes a dual role: illustrator and writer. However, when engaged with the dual disciplinary practice of illustration and authorship, how does one deal with the balance of text and image and which takes precedence? As an illustrator, it may be difficult not to allow the visual aspect to assume a significant presence. In practice, the majority of cases show that one’s audience connects with the perceived narrative by engagement with and elucidation by a sequence of illustrations accompanied by a relatively small amount of text that interacts simultaneously and corroborates either succinctly or literally the message given through the images. Examples of this form of practice are exemplified by word balloons in comics and the concise sentences and paragraphs contained in children’s picture books. Here, the illustrator is conceiving an imaginary tale that is original in terms of authorship. But is the intention for it to be renowned for high standards in creative writing? One is embarking on an inventive and innovative process that manifests in published form; therefore, the written aspect should match the illustrations in terms of standards and professional acceptability, even if the words are seen as an accompanying entity to the imagery.

Initially, one’s ownership, personal expression and choices made as creator and author can be given precedence over any notions of being commissioned in a standard commercial manner. This is where a publisher merely oversees the production of prescribed and heavily art-directed images. Any form of narrative fiction conceived by an author–illustrator, whatever mould envisaged for publication, will generally manifest as an entity comprising text and image. However, it is the content and essence of the invented story, its plot and setting that is of paramount importance.

It has been said previously that the conception of fictional narrative is a process that can allow one’s imagination and creativity to ‘fly’ free and unhampered. But it is important not to lose sight of one’s strengths and limitations regarding interests, inherent general and specific knowledge and sources of inspiration. These are factors that can initiate and facilitate a ‘spark’ of ideas and concepts for a potential story.

The working practice of author–illustrator has professional status, but one is rarely commissioned to produce a self-written and -illustrated fictional narrative. Therefore, one has complete uninhibited freedom to create. It is also necessary not to feel compelled to pursue a theme, plotline or genre seemingly dictated by contemporary fashion or trend. The most original and challenging stories often ‘buck the trend’. Whatever one’s particular interests and aspirations, it is fundamental to know and understand the parameters and distinctiveness of fictional genres and the possibilities afforded regarding one’s own practice. This also includes an awareness of one’s audience potential and appropriate media and publishing outlets.

‘‘THE CONCEPTION OF FICTIONAL NARRATIVE IS A PROCESS THAT CAN ALLOW ONE’S IMAGINATION AND CREATIVITY TO “FLY” FREE AND UNHAMPERED.’’

4.18–4.19

Chris Odgers

works within a niche of narrative fiction suited to a broad audience, including adults. He specifically writes and illustrates books that have a limited print run, whereby they acquire collectable edition status. The illustrations and text (written in verse) exemplify best practice in picture and word symbiosis.

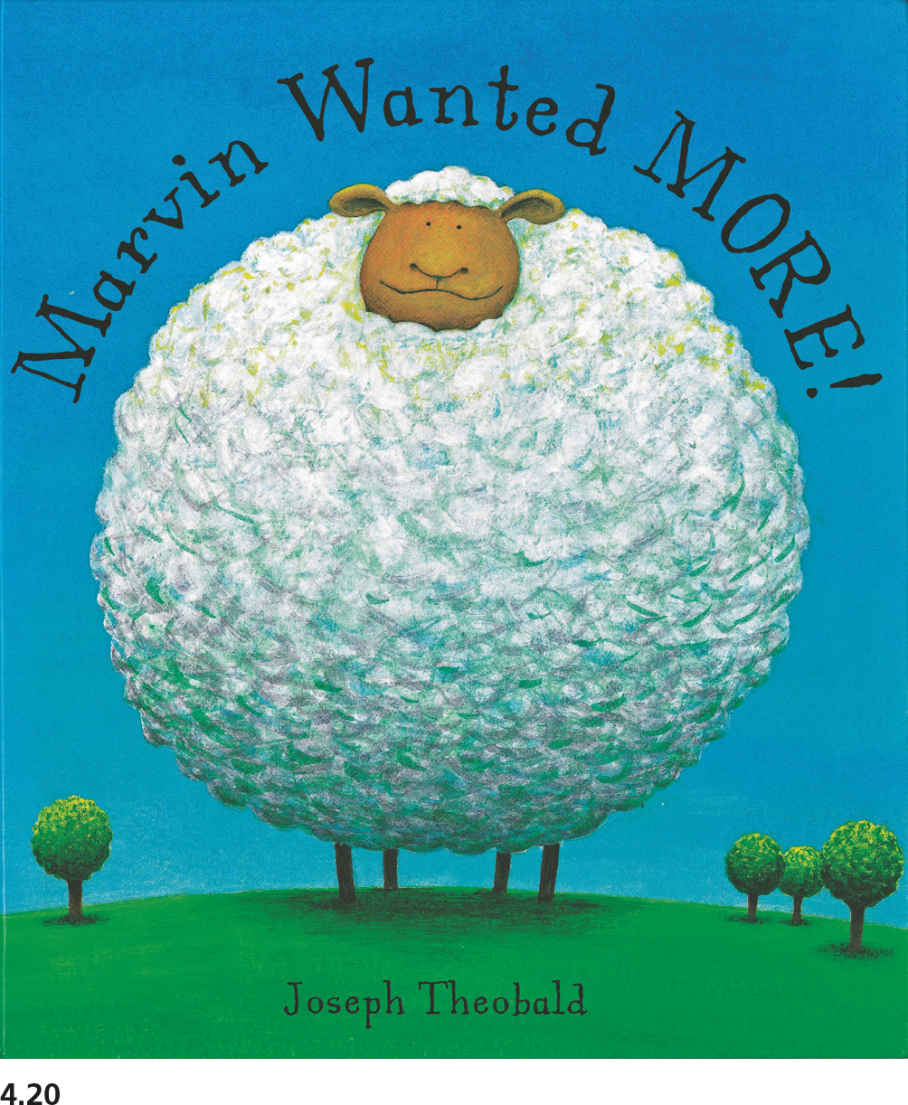

4.20

The children’s picture book is a medium that provides the most opportunities for illustrators to combine with authorship. This is the cover of Marvin Wanted More

, written and illustrated by Joseph Theobald

.

A Public Interface

Engagement with any form of communication in the public domain is not restricted to media platforms (i.e., online, broadcast or hard copy) at home, at work or in any other discrete or exclusive venue. Public space is there to be exploited by every professional design and communication context, with a potential audience comprising the broadest multi-cultural demographic. Town and city centres, other urban and built environments, landscapes and the countryside rarely escape some form of advertising or propaganda, public information systems, company, public or retail branding and identity and public art. The ‘artworks’ will often manifest as murals on walls and sides of buildings, advertising hoardings with static and digital moving imagery, sculptures, monuments and memorials, interactive three-dimensional features, live performances and broadcast. Hospitals, libraries and other public service locations or institutions will often commission illustrators to produce signage and information material or just decoration. This variety of output suggests it might not be easy to discern the remit or context of a ‘work’; where does illustration end and fine art begin? With inter-disciplinary procedures and the polymath principle prevailing as the norm for creative practice, perhaps it doesn’t matter.

It is likely that most, if not all, works accessed in the public realm will have been commissioned either to fulfil a commercial remit or as public art, with the intention of providing some local or national cultural identity, sense of place, or more specifically, community involvement and collaboration. Any project such as this would usually have to meet the approval of a local governing body. Some practitioners – including some extremely well known and celebrated artists – specialize in installation or public art.

4.21

The work of British artist Sir Antony Gormley

may be seen in many outdoor locations. He states that the rationale behind his work is ‘an attempt to materialize the place at the other side of appearance where we all live’. This photograph taken by the author is one of a 100 cast iron sculptures of the artist’s own body. Entitled ‘Another Place,’ the sculptures, all facing out to sea, are permanently located on Crosby Beach, north of Liverpool, England.

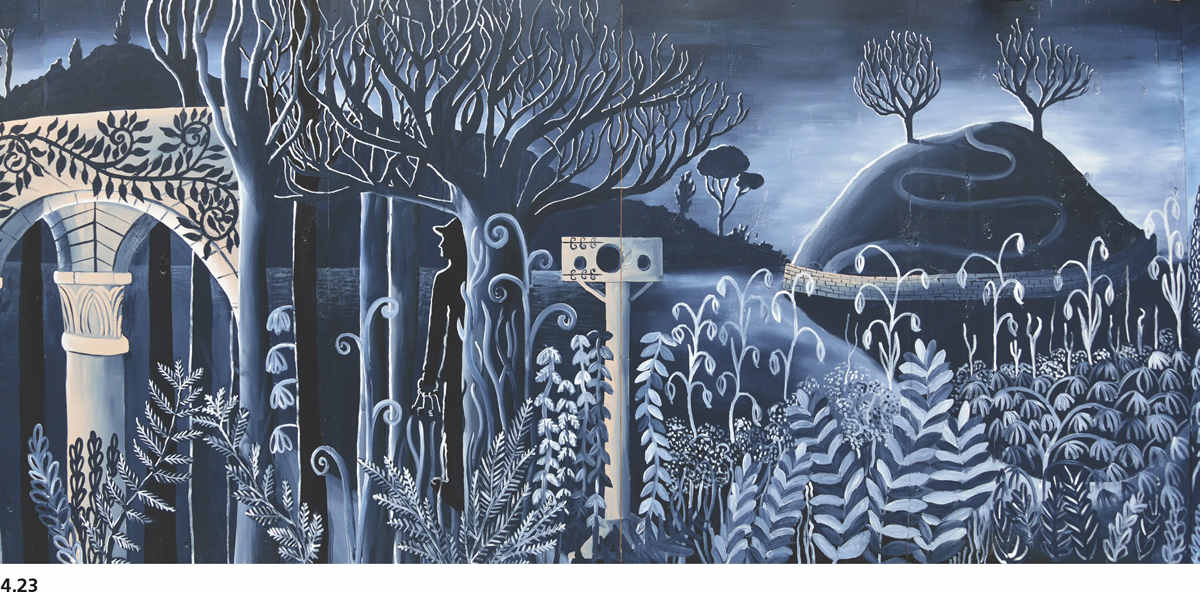

4.22–4.23

This mural has been researched, designed and illustrated by Charlotte Orr

and stretches the full length of a 120 feet (approximately 40 metres) courtyard within the city of Oxford, England. The mural, which was entirely painted by hand, can be accessed within the Oxford Castle Quarter and was Winner of the World Illustration Award, Public Realm category, 2015. The image conveys a mystical and ethereal narrative containing scenarios from the castle’s history.

CONNECTIVITY AND INTERACTION

It is becoming increasingly prevalent for a variety of organizations – public, commercial or heritage – to facilitate events or other such activities that invite people to participate by learning through workshops, live exhibitions, play or entertainment. These activities can be sponsored as free or subscription events and are normally open to any interested party irrespective of age or experience. Sometimes they can be part of a modest charitable event, as an element within a large-scale arts–music festival or facilitated by business; this might mean being part of a commercial promotion or alternatively for ‘altruistic’ reasons by ‘putting something worthwhile back into the community’. Also, heritage centres such as museums or large historical and cultural preservation organizations like The National Trust in England have a remit for ‘educating the public’ and will feature interactive exhibits, practical artefacts, lectures and educational activities for children.

So, where might the illustrator contribute? The Society of Illustrators in New York, the first of its kind and established in 1901, has a mission to ‘promote the art of illustration; to appreciate its history and evolving nature through exhibitions, lectures and education; and to contribute the service of its members to the welfare of the community at large’. This particular remit is generally universal across many similar organizations such as societies, guilds, galleries, associations and clubs that represent a wide range of professional (and amateur) visual communication, design and craft disciplines.

FINAL THOUGHTS

To summarize, illustration is seen everywhere. Its effect and impact are deeply rooted in societies all over the globe. As for the future, people everywhere will continue to seek new knowledge, be seduced by new products and services, demand more and more entertainment and illustration will be at the heart of all of this.

The essence and parameters of illustration will ebb and flow in accordance with societal need and technological and media advancements, but as a discipline, it will continue to be as essential and influential as before.

4.24–4.29

Mis Led

, AKA Joanna Henly, is an award-winning illustrator whose work spans fashion, branding and promotions. As well as producing illustration work in traditional print and digital formats, murals and installations, she facilitates and leads many workshops for community organizations, business and commerce, artists, illustrators, designers and galleries. A typical example features a portraiture workshop held for VANS in London and La Galeria Roja, Seville, which enabled groups and individuals from media professionals to bloggers and drop-in art lovers to ‘turn their hand to illustration for the first time’.

The imagery shown is a composite of various artworks produced and workshops given from a live painting commission to celebrate the launch of DRAW, an exhibition at the Printspace Gallery, London; a four-wall room installation for the ‘Eye Candy Festival’ of Popular Culture in Birmingham, England; Book Club to Saatchi Gallery, London; and a Narrative Portraiture Workshop: Working with Words