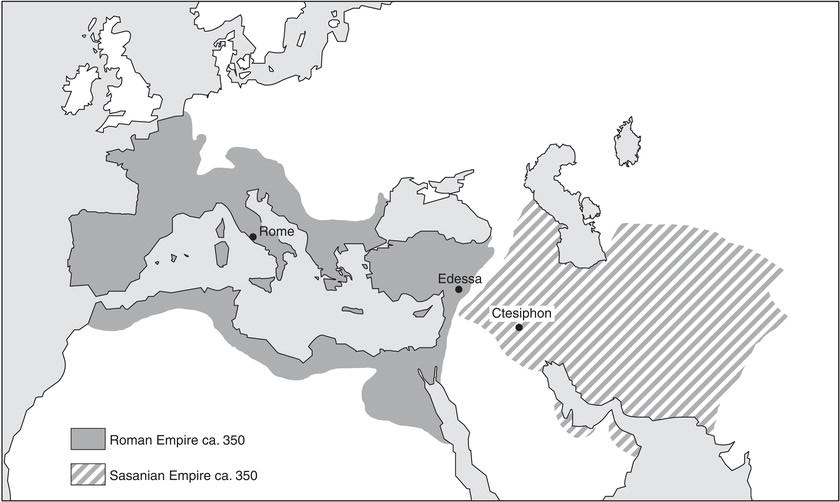

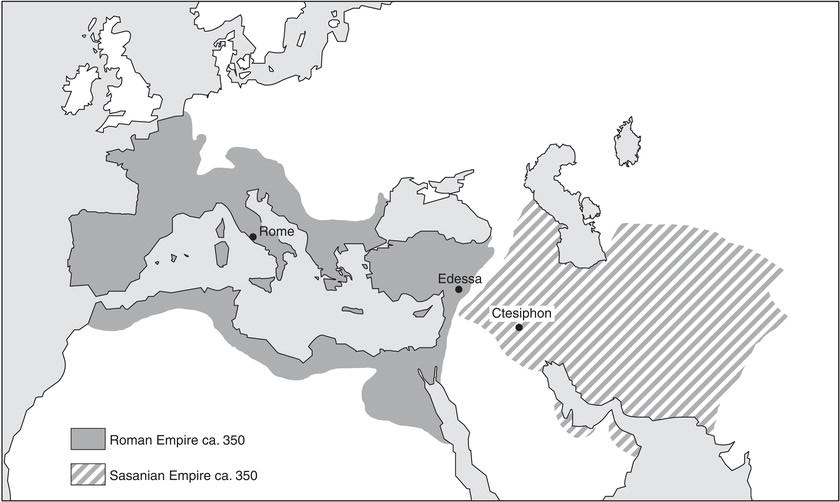

Map 1 The world ca.350: the Roman and Sasanian empires

To ensure that we see the history of western Europe in its true perspective, we should begin our account in a city far away from modern Europe. Edessa (modern Urfa) now lies in the southeastern corner of Turkey, near the Syrian border. In the year A.D. 200, also, it was a frontier town, positioned between the Roman and the Persian empires. It lay at the center of a very ancient world, to which western Europe seemed peripheral and very distant.

Edessa was situated at the top of the Fertile Crescent, the band of settled land which stretched, in a great arch, to join Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean coast. It lay in a landscape already settled for millennia. Tels – the hill-like ruins of ancient cities dating back to the third millennium B.C. – dot the plain around it. Abraham was believed to have resided in Harran, a city a little to the south of Edessa, and to have passed through Edessa, as he made his way westward from Ur of the Chaldees in Mesopotamia, to seek his Promised Land on the Mediterranean side of the Fertile Crescent.

To the west of Edessa, an easy journey of 15 days led to Antioch and to the eastern Mediterranean, the sea which formed the heart of the Roman empire. To the southeast, another journey of 15 days led to the heart of Mesopotamia, where the Tigris and the Euphrates came closest. This was a zone of intensive cultivation which had supported the capitals of many empires. Here Ctesiphon was founded, in around A.D. 240. Its ruins now lie a little to the south of modern Baghdad. Ctesiphon was the Mesopotamian capital of the Sasanian dynasty, a family from southwest Iran, who took over control of the Persian empire in A.D. 224. The Sasanian empire joined the rich lands around Ctesiphon to the Iranian plateau. Beyond the Iranian plateau lay the trading cities of Central Asia and, yet further to the east, the chain of oases that led the traveller, over the perilous distances of the Silk Route, to the legendary empire of China.

Map 1 The world ca.350: the Roman and Sasanian empires

CHRISTIANITY AND EMPIRE ca. 200–ca. 450

| Bardaisan 154–ca.224 224 Rise of Sasanian Empire Mani 216–277 | |

| 257 Edict against Christians | |

| Cyprian, bishop of Carthage 248–258 | |

| 284–305 Diocletian 303 Great Persecution | |

| 306–337 Constantine 312 Battle of Milvian Bridge 324 Foundation of Constantinople 325 Council of Nicaea | |

| Anthony 250–356 Arius 250–336 Athanasius of Alexandria 296–373 | |

| 337–361 Constantius II | |

| Martin of Tours 335–397 Ambrose of Milan 339–397 Melania the Elder 342–411 Paulinus of Nola 355–431 | |

| 378 Battle of Adrianople 379–395 Theodosius I 390 Massacre of Thessalonica | |

| Augustine of Hippo 354–430 writes Confessions 397/400 | |

| 406 Barbarian invasion of Gaul 410 Sack of Rome | |

| writes City of God 413+ Pelagian Controversy 413+ | |

| 408–450 Theodosius II as Eastern emperor | |

| 438 issues Theodosian Code | |

| 434–453 Empire of Attila the Hun |

In the early third century, Edessa was the capital of the independent kingdom of Osrhoene. Bardaisan (154–222) was a nobleman and learned figure at the royal court. He represented the complex strands of a culture which drew on both the East and the West. Greek visitors admired his skills as a Parthian (Persian) archer. But, as a philosopher, he was entirely Greek. When a faithful disciple wrote a treatise summarizing Bardaisan’s views on the relation between determinism and free will, he began it with a Platonic dialogue between two Edessene friends, Shemashgram and Awida. Yet the dialogue was not written in Greek but in Syriac, a language which was soon to become a major literary language in the Christian churches of the Middle East.

Bardaisan, furthermore, was a Christian, at a time when Christianity was still a forbidden religion within the Roman empire. He interpreted his faith in broad, geographical terms. The point that he wished to make was that, wherever they lived, human beings were free to choose their own way of life. They were not determined by the influence of the stars. Each region had its own customs, and Christians showed the extent of the freedom of the will by ignoring even these customs, and by seeking, rather, to live under “the laws of the Messiah” – of Christ. “In whatever place they find themselves, the local laws cannot force them to give up the law of the Messiah.”

Bardaisan’s treatise was appropriately named The Book of the Laws of Countries. It scanned the entire Eurasian landmass from China to the north Atlantic. It described the local customs of each society – the caste-dominated society of northern India, the splendidly caparisoned horses and fluttering silk robes of the Kushan lords of Bokhara and Samarkand, the Zoroastrians of the Iranian plateau, the Arabs of Petra and of the deserts of Mesopotamia. It even turned to the remote west, to observe the impenitent polyandry of the Britons. Naturally, it included the Romans, whom no power of the stars had ever been able to stop “from always conquering new territories.”1

Any book on the role of Christianity in the formation of western Europe must begin with the sweep of Bardaisan’s vision. This book studies the emergence of one form of Christendom only among the many divergent Christianities which came to stretch along the immense arc delineated in Bardaisan’s treatise. We should always remember that the “Making of Europe” involved a set of events which took place on the far, northwestern tip of that arc. Throughout the entire period covered by this book, as we shall see, Christians were active over the entire stretch of “places and climates” which made up the ancient world of the Mediterranean and western Asia. Christianity was far from being a “Western” religion. It had originated in Palestine and, in the period between A.D. 200 and 600, it became a major religion of Asia. By the year 700 Christian communities were scattered throughout the known world, from Ireland to Central Asia. Archaeologists have discovered fragments of Christian texts which speak of basic Christian activities pursued in the same manner from the Atlantic to the edge of China. Both in County Antrim, in Northern Ireland, and in Panjikent, east of Samarkand, fragmentary copybooks from around A.D. 700 – wax on wood for Ireland, broken potsherds for Central Asia – contain lines copied from the Psalms of David. In both milieux, something very similar was happening. Schoolboys, whose native languages were Irish in Antrim and Soghdian in Panjikent, tried to make their own, by this laborious method, the Latin and the Syriac versions, respectively, of what had become a truly international, sacred text – the “Holy Scriptures” of the Christians.2

Less innocent actions also betray the workings of a common Christian mentality. As we shall see, the combination of missionary zeal with a sense of cultural superiority, backed by the use of force, became a striking feature of early medieval Christian Europe. But it was not unique to that region. In around 723, Saint Boniface felled the sacred oak at Geismar and wrote back to England for yet more splendid copies of the Bible to display to his potential converts. They should be “written in letters of gold … that a reverence for the Holy Scriptures may be impressed on the carnal minds of the heathen.”3

At much the same time, Christian Nestorian missionaries from Mesopotamia were waging their own war on the great sacred trees of the mountain slopes that rose above the Caspian. They laid low with their axes “the chief of the forest,” the great sacred tree which had been worshipped by pagans. Like Boniface, the Nestorian bishop Mar Shubhhal-Isho’ knew how to impress the heathen: he

made his entrance there with exceeding splendor, for barbarian nations need to see a little worldly pomp and show to attract them to make them draw nigh willingly to Christianity.4

Even further to the east, in an inscription set up in around A.D. 820 at Karabalghasun, on the High Orkhon river, the Uighur ruler of an empire formed between China and Inner Mongolia, recorded how his predecessor, Bogu Qaghan, had introduced new teachers into his kingdom in A.D. 762. These were Manichaeans. As bearers of a missionary faith of Christian origin, the Manichaean missionaries in Inner Asia shared with the Nestorians a similar brusque attitude toward the conversion of the heathen. The message of the inscription is as clear and as sharp as that which Charlemagne had adopted, between 772 and 785, when he burned the great temple of the gods at Irminsul and outlawed paganism in Saxony. Bogu Qaghan said:

We regret that you were without knowledge, and that you called the evil spirits “gods.” The former carved and painted images of the gods you should burn, and you should cast far from you all prayers to spirits and to demons.5

It goes without saying that these events had no direct or immediate repercussions upon each other. Yet they do bear a distinct family resemblance. They show traces of a common Christian idiom, based upon shared traditions. They remind us of the sheer scale of the backdrop against which the emergence of a specifically western Christendom took place.

The principal concern of this book, however, will be to characterize what, eventually, would make the Christendom of western Europe different from that of its many, contemporary variants. In order to do this, let us look briefly at another aspect of Bardaisan’s geographical panorama. The vivid gallery of cultures known to him appeared to stretch from China to Britain along a very narrow band. Bardaisan was oppressed by the immensity of the unruly, underdeveloped world of the “barbarians,” which stretched to the north and south of the civilized world. Grim stretches of sparsely populated land flanked the vivid societies he described.

In the whole regions of the Saracens, in Upper Libya, among the Mauritanians … in Outer Germany, in Upper Sarmatia … in all the countries North of Pontus [the Black Sea], the Caucasus … and in the lands across the Oxus … no one sees sculptors or painters or perfumers or money changers or poets.

The all-important amenities of settled, urban living were not to be found “along the outskirts of the whole world.”6

It was a sobering vision, shared by most of Bardaisan’s Greek and Roman contemporaries. It was eminently appropriate in a man bounded by two great empires – the Roman and the Persian. These two great states controlled, between them, most of the settled land of Europe and western Asia. Both were committed to sustaining the belief, among their subjects, that their costly military endeavors were directed toward defending the civilized world against barbarism. In the words of a late sixth-century diplomatic manifesto, sent by the Persian King of Kings to the Byzantine emperor:

God effected that the whole world should be illuminated from the beginning by two eyes [the Romans and the Persians]. For by these greatest powers the disobedient and bellicose tribes are trampled down and man’s course is continually regulated and guided.7

It is against the backdrop of a vast world patrolled by two great empires, which stretched with little break from Afghanistan to Britain, that we begin our story of the rise and establishment of Christianity in western Europe.

The empires which controlled the settled lands invariably presented themselves as defending “civilization” against the “barbarians.” Yet what each empire meant by “barbarian,” and the relations which each established with the “barbarians” on its own frontiers, varied markedly from region to region. Western Europe became what it now is because the relations which the Roman empire established with the “barbarians” along its northern frontiers proved to be quite unusual. Compared with the relations between the ancient empires of the Middle East and the nomads of the Arabian desert and of the steppes of Central Asia, the “barbarians” of the Roman West were hardly “barbarians” at all. For they were farmers, not nomads.

We must always remember that “barbarian” meant many things to Bardaisan and his contemporaries. It could mean nothing more than a “foreigner,” a vaguely troubling, even fascinating, person from a different culture and language-group. By this criterion, Persians were “barbarians.” To Greeks and to an easterner such as Bardaisan, even Romans were “barbarians.” But, for Bardaisan as for most Greeks and Romans, “barbarian” in the strong sense of the word meant, in effect, “nomad.” Nomads were seen as human groups placed at the very bottom of the scale of civilized life. The desert and the sown were held to stand in a state of immemorial and unresolved antipathy, with the desert always threatening, whenever possible, to dominate and destroy the sown.8

In North Africa and the Middle East, of course, there was little truth in this melodramatic stereotype. For millennia, pastoralists and peasants had collaborated, in a humdrum and profitable symbiosis. Nomads were treated as a despised but useful underclass. It was assumed that these wanderers, though often irritating, could never constitute a permanent threat to the great empires of the settled world, much less replace them. Because of a contempt for the desert nomad which reached back, in the Middle East, to Sumerian times, the Arab conquests of the seventh century (the stunning work of former nomads) and the consequent foundation of the Islamic empire took contemporaries largely by surprise. Wholesale invasion and conquest from the hot desert of Arabia had not been expected.

The nomads who had always been feared (and with reason) were, rather, those of the cold north, from the steppelands which stretched from the puszta of Hungary, across the southern Ukraine, to Central and Inner Asia. Here conditions favored the intermittent rise of aggressive and well-organized nomadic empires.9 Herds of fast, sturdy horses bred rapidly and with little cost on the thin grass of the northern steppes. These overabundant creatures, when mounted for war, gave to the nomads the terrifying appearance of a nation in arms, endowed with uncanny mobility. One such confederacy of Huns from Central Asia penetrated the Caucasus into the valleys of Armenia, in the middle of the fourth century:

no one could number the vastness of the cavalry contingents [so] every man was ordered to carry a stone so as to throw it down … so as to form a mound … a fearful sign [left] for the morrow to understand past events. And wherever they passed, they left such markers at every crossroad along their way.10

The sight of such cairns was likely to stick in the memory. Unimpressed by the desert nomads of Arabia and the Sahara, the rulers of the civilized world scanned the nomadic world of the northern steppes with anxious attention.

Yet, terrifying though the nomadic empires of the steppes might be, they were an intermittent phenomenon. Effective nomadism, in its normal state, depended on the maximum dispersal of families, each maintaining the initiative in maneuvering its flocks toward advantageous pasture, with a minimum of interference from a central authority. To change from herding scattered flocks to herding human beings, through conquest and raiding, under the leadership of a single ruler, was an abnormal and, usually, a shortlived development in the long history of the nomadic world. Even a mighty warlord such as Attila (434–453), despite the fact that he has left an indelible mark on the European imagination, found that his ambitions were subject to insurmountable limits. His ability to terrorize the inhabitants of the settled land was subject to an automatic “cut-off.” The further from their native steppes the Huns found themselves, the less access they had to those pastures that provided the vast surplus of horses on which their military superiority depended. For a few chilling decades, Attila had extorted tribute from the Roman world. But, within a year of his death in 453, his famous Hunnish empire disintegrated and vanished as if it had never existed.11

As a result, the nomadic confederacies played a peripheral role in the history of Europe. The Huns, in the fifth century A.D., were succeeded by the Avars, in the seventh and eighth centuries A.D. But the Avars also settled down, after a few decades of spectacular saber-rattling. What the Huns and the Avars brought, in the long run, was not the end of the world, as many had feared at the time, but a hint of the immense spaces which lay behind them. The nomad confederacies of eastern Europe and the Ukraine were the westernmost representatives of an international Eurasian world whose vast horizons the settled societies of Europe could barely rival. The movement of precious objects and the borrowing of customs showed this. Garnets from northern Afghanistan, set in intricate gold-work that echoed the flying beasts and coiled dragons of Central Asia and China, flowed into the Danubian court of Attila. By the mid-fifth century, such jewelry formed an international “barbarian chic,” a sign of high status sported alike by Roman generals and by local kings. Hunting with hawks entered western Europe from Central Asia at this time; and, in the eighth century, the crucial development of stirrups spread to western horsemen as a result of Lombard–Avar contacts in the region between the Danube and Friuli. Up to almost the end of our period, the Avar governor commanding the regions bordering on Vienna still bore a name that was a distant echo of the official title of a Chinese provincial governor.12

In eastern Europe, the nomads remained a constant presence throughout this period and beyond. In western Europe, however, the true nomad world, which produced Attila and, later, the Avars, remained remote if imposing. It is important to emphasize this fact. True nomads were rare in western Europe, yet Romans tended to assimilate all “barbarians” to the rootless and violent image of the nomads which was so current in the ancient world.

Our own image of the barbarians has been colored by Roman attitudes. With us, also, the “barbarian” stands for all that was most mobile and dangerous beyond the frontiers of Rome. In reality, relations between Romans and “barbarians” in western Europe evolved in a significantly different manner. The opposition between “settled” and “barbarian” regions had been charged with great weight for a man of the Near East such as Bardaisan because it was thought to coincide with the ancient opposition between farmers and nomads. But such an opposition was not appropriate when applied to the Roman frontiers of Britain, the Rhine, and the Danube. The ideology of the settled world made it appear as if a chasm separated the populations contained within the frontiers of the Roman empire from the barbarians gathered outside. Their life was portrayed as incommensurable with that of civilized persons, as if it was, indeed, the same as the life of the nomads of the steppes and the deserts.

But the populations of northwestern Europe were not nomads. There was no place along the European frontiers of the Roman empire for the stark ecological contrast between the desert and the sown which made the settled populations of North Africa and the Middle East feel so different from their “barbarian” neighbors. Rather, Roman and non-Roman landscapes merged gently into each other, within a single temperate zone.

If we were to follow only the texts written by Roman authors, we would have little idea of the extent to which life in the world beyond the Roman frontier of the Rhine and the Danube resembled the life of many rural areas within the Roman empire itself. Nor could we guess the extent to which the “barbarian” world came to be molded by the presence of Rome. It is only in the last decades, indeed, that spectacular finds in Germany and Denmark and the new interpretative skills applied to these finds by archaeologists have enabled us to allow the “barbarian” half of Europe to “speak” in its own voice.13 And what we hear is a world slowly penetrated, on every level, by Roman goods, by Roman styles of living and, eventually, by Roman ideas.

When we enter “free” Germany (as the Romans called it) we do not find creatures from another world. Rather, we have entered a “peripheral economy” attached, in innumerable ways, to the new world created by the Roman empire along the frontiers of the Rhine and the Danube: warriors are buried with Roman swords; chieftains sport Roman dining sets; a kiln for pottery identical with those used in Roman Gaul is set up in Thuringia, over 100 miles east of the Roman frontier. It is the closeness of Rome to central Europe that is surprising, not the notional chasm between “Romans” and “barbarians.”

Certain contrasts of terrain between the Roman territories and “free” Germany struck Roman observers. They described the heathlands of the north German plain with their herds of half-wild cattle and the somber, primeval forests which covered the hills of central and southern Germany. But, despite these contrasts, the lands outside the Roman frontiers were inhabited by peoples who shared with the provincial subjects of the Roman empire, in Britain, Gaul, and Spain, the same basic building-blocks of an agrarian society. They too were peasants. They, too, struggled to wrest their food from the heavy, treacherous earth, “the mother of men.”

Their overall population was low. It was more dispersed than was the case in many Roman provinces. Farming communities lived in isolated groups of homesteads and in small hamlets, cut off from each other by stretches of forbidding forest and moorland. The villages excavated by archaeologists rarely seem to have contained more than 300 inhabitants. Yet, as is shown in the case of the village excavated at Feddersen Wierde, near Bremerhaven on the north German coast, these could be stable settlements, laid out with care; large barns and buildings hint at increasing social differentiation over the centuries. Along the North Sea coast of Frisia, beyond the last Roman garrisons, the inhabitants defended the arable land against the saltwater tides with the same skill and tenacity as did their neighbors across the sea, the nominally “Roman,” British peasants of the Fenland.

Crucial skills of metalworking were practiced; but such skills were virtually invisible to Roman eyes, taking place as they did in the smithies of tiny villages, unconnected by the overarching political and commercial structures which enabled the Romans to bring so much metalwork together, with such deadly effect, in the armaments of their legions. When the German tribes fought each other, the armies they raised were minute and ill-equipped by Roman standards. A German “army” reconstructed from finds at Illerup (in Denmark) seems to have had 300 soldiers armed only with spears, 40 heavily armed warriors, and five leaders. The swords of the elite in this small force were all of them Roman swords.14

Livestock played a prominent role among the “barbarian” peoples of the north European plain and elsewhere. Livestock promoted more dispersed patterns of settlement. It was the focus of intense, upper-class competition for mobile wealth, as in the great cattle raids of Irish epic and in the solemn cattle-tributes which expressed the power of chieftains in Germany. Pastoralism on this scale seemed rootless to Romans, who were used to a well-disciplined peasantry, tied to the land and engaged in a labor-intensive agriculture based on cereal crops. But abundant cattle gave greater access to protein, in the form of meat and dairy products, than was common among the undernourished peasants of the Mediterranean. Hence the pervasive sense, among Romans, of the “barbarian” North as a reservoir of mobile and ominously well-fed young warriors. A Roman military expert wrote that “the peoples of the North” live far from the sun. As a result, they have more blood in their bodies than do the inhabitants of the sun-soaked Mediterranean, whose bodies are “dried up” by heat. No wonder that they make such formidable soldiers!15

Thus, though viewed by the Romans as “barbarians”, the populations of northern and eastern Europe were, first and foremost, farmers. The moment that Germanic villagers and ranchers found themselves confronted by true nomads, such as the Huns, they had no illusion about which world they belonged to. We can see this in the 370s. The first populations encountered by the Huns as they infiltrated the steppelands of southern Russia at this time were the Goths. The Goths were settled to the north of the Danube. Their villages stretched from Transylvania and Moldavia into the southern Ukraine. They were an agrarian people, northern representatives of a peasant economy which had come to cover the landscape, since prehistoric times, in an uninterrupted band that stretched from the Mediterranean to central Europe and the southern Ukraine.16

When the Gothic villagers in Moldavia and the Ukraine began to be subjected to Hunnish raids, in 374, their first reaction was to seek permission to place the Danube between themselves and the Huns by settling in the Roman empire. In return for an offer to provide regular military service, they were allowed to become Roman subjects. They crossed the Danube not so as to “invade” the Roman empire, but as immigrants, who sought to resume their lives as farmers, in a Roman landscape no longer overshadowed (as the Ukraine had come to be) by the truly alien nomads.

Politically, the arrangement turned into a disaster: driven by famine and enraged by the systematic exploitation of their refugee camps, the remnants of the Gothic nobility (soon renamed and known to us ever since as the Visigoths) rallied its warriors to defeat and kill the eastern emperor at Adrianople (Edirne, European Turkey) in 378. Alaric, a Visigothic king, eventually sacked Rome in 410, in the course of a prolonged and inconclusive attempt to gain admission to the Roman high command. But this breakdown of relations happened only after the Visigoths had opted to appeal to Rome against the Huns and the Romans had allowed them in. To call the entry of the Goths into the Roman empire a “barbarian invasion” is profoundly misleading. Despite its unforeseen and damaging consequences, this was a controlled immigration of displaced agriculturalists, anxious to mingle with similar farmers on the Roman side of the frontier. Seen in terms of the long-term history of a shared agrarian civilization which had developed throughout temperate Europe since prehistoric times, the Roman frontier did not mark a chasm between two totally different worlds. It was an artificial divide, destined, within a few centuries, to become irrelevant.

We must realize, however, that, in the year 200, few Romans appreciated these facts. The ideology expressed by a writer such as Bardaisan was widespread among educated persons in the Latin- and Greek-speaking worlds. “I expect no more to have Germans among my readers,” wrote the famous Greek doctor, Galen of Ephesus, an older contemporary of Bardaisan, “than I would expect to be read by bears and wolves.”17

Such jaundiced views are not altogether surprising. Looking across from their side of the frontier, the Romans saw a society which, by their standards, was totally illiterate. Apart from runes, which developed at this time but were used more for magic than for purposes of communication, the “barbarian” world was a world of entirely oral culture. It was also, palpably, a society dominated by its warriors. Compared with the peasants and slaves who supported them, the warriors of “free Germany” were only a small proportion of the males of each tribe. But they dominated their own societies. Prestige, leisure, access to resources (and especially access to abundant food which would be consumed with gusto in heavy feasting as a sign of the superior status of warriors) and, above all, “freedom” – the crucial freedom of males from dependence on the arbitrary commands of others (as slaves and as serfs) – depended on the ability of young males to participate in battle.

It was the warrior upper crust of “barbarian” society which the Romans watched closely. But they did not do so, inevitably, with anxious attention, in the expectation of imminent invasion. Far from it. What they saw, rather, was a vast and “underdeveloped” landscape whose principal “cash crop,” as it were, was an abundant surplus of violent young men. What changed central Europe in the years between A.D. 200 and 400 was not so much an increase of “pressure” on the part of “barbarian” tribes against the Roman frontier. It was the increased “presence” in “free” Germany itself of the Roman empire as a land of opportunity.

The frontier region became a vortex which sucked warrior groups toward it. Faced by a harvest of young men which was so easy to garner, the Roman authorities changed their recruiting grounds from the Roman to the German side of the frontier. Germans rather than provincials filled the ranks of the armies. They served first in “auxiliary” units, but increasingly as fully trained professionals. The emperors always needed troops to fight the bitter civil wars which characterized the third and fourth centuries. This need for soldiers to fight in civil wars sucked Germans across the frontier into wars where, at regular intervals, Romans set about killing Romans, in the deadly clash of fully professional armies, in far greater numbers than they ever expected to kill or to be killed when fighting “barbarians.”

As a result of this development, already by the year A.D. 300 a “para-Roman” world, long accustomed to Roman ways and deeply involved in Roman politics, had grown up along the Rhine and the Danube. Far from threatening the Roman order as if from an untamed “barbarian” hinterland, many of the leaders of these warrior societies had already been called upon, in the course of civil wars and even as career soldiers in the Roman high command, to act as the representatives of that Roman order.18

Altogether, along the frontier, things were not quite as they appeared. The arrival of the Roman empire in northwestern Europe had set in motion a process which reached its inevitable (but largely unexpected) culmination in our period.

In the first and second centuries A.D., the establishment of large Roman armies on the frontiers and the foundation of Roman-style cities behind them brought wealth and demands for food and labor which revolutionized the countryside of northern Gaul, Britain, and the Danubian provinces. These regions were suddenly subjected to unparalleled demands. At the mouth of the Rhine, a population of less than 14,000 had to find room for legionary garrisons of over 20,000. The garrisons of northern Britain ate enough food to keep 30,000 acres of land under permanent cultivation. At least 12,000 cattle were needed to supply the Roman army in Britain with leather for its tents and its boots.

On the Roman side of the frontier, hitherto unimaginable coagulations of human population were gathered into newly founded towns. Trier, London, Paris, and Cologne had populations of up to 10,000, even 20,000. They were small-scale yet impressive echoes, in northern Europe, of an urban life associated with the Mediterranean: at this time, Rome had a population which reached a million; the populations of Alexandria, Antioch, and, later, of Constantinople could be counted in hundreds of thousands.

But the towns were only one aspect of a wider process. All over the northern provinces of western Europe the huge fact of empire settled its slow weight on the land. Agrarian society was congealed into more solid structures, designed to aid the permanent extraction of wealth from the tillers of the land. Behind the frontiers, in northern Gaul, great, grain-producing villas (whose owners even experimented with primitive harvesting machines) came to dominate an increasingly subservient peasantry.

It was in this way that the Roman frontier, set in place to separate the Roman world from the squalid lands to its north, became the unwitting axis along which the Roman and barbarian worlds converged. Like a wide depression formed by the weight of a glacial ice-pack, the frontiers of the Roman empire, maintained at the cost of crushing expenditure of wealth and characterized by dense concentrations of settlement, created a novel catchment area. The economic and cultural life of the lands beyond the frontier began to flow into this catchment area. We can see this in small details. Roman garrisons along the estuary of the Rhine came to purchase grain and cattle in the non-Roman territories. The first lines of Latin ever written from beyond the Roman frontiers take the form of a purchase order for a Frisian cow, discovered near Leeuwarden in northern Holland.19

The Roman frontiers in Europe were more porous than we think. The spread of Latin loan words in German and Old Irish; the recurrence of Roman motifs in the gold-work of Jutland; the fact that ogham, the archaic script cut along the edge of wooden tallies and on standing stones in Ireland, followed a categorization of the consonants propounded by Roman grammarians: these details show a barbarian world slowly changing shape under the distant gravitational pull of the huge adjacent mass of the Roman empire.20

As a result of this development, what happened after the year 400 was not what we imagine to have happened when we think of the “fall” of the Roman empire in the West. The Roman frontier was not violently breached by barbarian “invasions.” Rather, between 200 and 400, the frontier itself changed. From being a defensive region, which kept Romans and “barbarians” apart, it had become, instead, an extensive “middle ground,” in which Roman and barbarian societies were drawn together.21 And after 400, it was the barbarians and no longer the Romans who became the dominant partners in that middle ground. The Middle Ages begin, not with a dramatic “fall of Rome,” but with the barely perceived and irreversible absorption, by the “barbarians,” of the “middle ground” created in the Roman frontier zone.

This development, of course, did not happen without suffering and bloodshed. To take one example from northern Britain in the middle of the fifth century A.D.: Saint Patrick (ca.420–490) did not first visit Ireland of his own free will. Patricius (to use his true Roman name) was brutally swept away from his home by Irish slave raiders. A young man who might have gone on to polish his Latin in the Roman schools of Britain found himself set to herding pigs on the rain-lashed coast of County Mayo.

But Patricius’ subsequent return to Ireland and the slow implantation of Christianity in what had been an entirely non-Roman island reveals a world that was not entirely dominated by violence. What happened in Patricius’ lifetime was the emergence of the Irish Sea as a Celtic “Mediterranean of the North.” Around the Irish Sea, the Romanized coasts of Wales and northern Britain were joined to Ireland and the western isles of Scotland to form a single zone which ignored the former Roman frontiers. In exactly the same period, the Frankish kingdom created by Clovis (481–511) represented a return to the days before Julius Caesar, when successful warrior kings had straddled the Rhine to join Germany with the “Belgic” regions of northern Gaul.

This development coincided with religious changes. The development which we tend to call “the coming of Christianity to the barbarians” has always been acclaimed as the beginning of the western Middle Ages. But seen in a longer perspective, it was no more than the last, most clearly documented and best-remembered phase in the long process by which Roman and “barbarian” regions of northwestern Europe came together along the “middle ground” to form a new zone of high culture.

Western Europe itself looked very different when viewed from the former frontier zones of the empire and no longer exclusively (as Romans had done) from the perspective of Rome and the Mediterranean. To a person of around the year A.D. 700, there was nothing strange in the fact that some of the most polished Latin scholarship of the age should have been produced in monasteries founded by Saxon kings and aristocrats of the kingdom of Northumbria, in what had once been the frontier zone between York, Hadrian’s Wall, and southern Scotland. The monasteries of Jarrow and Monkwearmouth, with their well-stocked Latin libraries, which produced a scholar of the caliber of the Venerable Bede (672–735), and the spectacular “Roman-style” buildings set up in northern Britain by bishop Wilfrid (634–709), should not be seen as miraculous oases of “Roman” culture perched, somewhat improbably, at the furthest ends of the earth. They may have been far from Rome, but they lay at the center of a whole new world of their own. From Iona, on the southwestern coast of Scotland, across Anglo-Saxon Britain, to northern Gaul, Bavaria, and, ultimately, to central and northern Germany, a new world had come into being around the former Roman frontiers. The northern Britain associated with the “Golden Age” of Bede (which is well known to British readers) was only one region of the former “middle ground” which blossomed at this time. From Ireland all the way to the Danube, centers of Christian learning came to flourish in what had once been the “barbarian” side of the Roman frontier. Early medieval Christianity was at its most vigorous in regions which, half a millennium previously, had been regarded by cultivated Romans as lands beyond the pale of civilization.

But this, of course, is to anticipate. In the next two chapters, we must turn to the nature of Christianity itself as it developed within the territories of a changed Roman empire in the period between A.D. 200 and 400.