3

THE CIRCUITS

TRIUMPH AND TRAGEDY ON F1’S COURSES

Best of both worlds for Ferrari at Suzuka in 2003 after Rubens Barrichello (with crash helmet) has won the Japanese Grand Prix and Michael Schumacher has become World Champion.

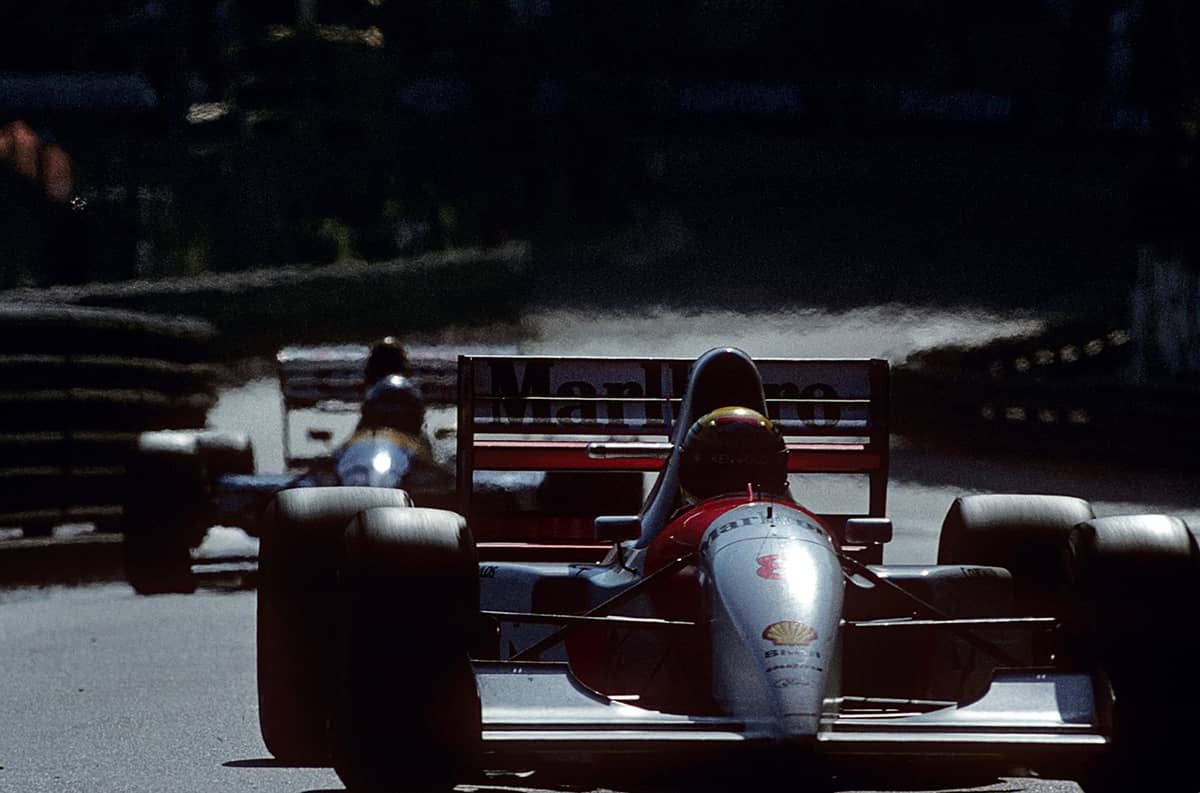

Monaco: the most famous of them all. Mika Hakkinen locks his brakes behind Michael Schumacher as the Ferrari and McLaren-Mercedes lead the pack into the first corner at the start of the 1999 Monaco Grand Prix.

There have been more than seventy different race tracks used to stage Grands Prix since the start of the World Championship in 1950. Some have been used just once. Others, such as Monaco and Monza, have provided a perpetual showcase just as intoxicating and passionate as the sport itself.

The striking difference between these two traditional venues sums up the variety that makes F1 what it is. And the fact that both Monza and Monaco have been responsible for the writing of racing drivers’ obituaries also underscores the tragedy that occasionally stalks the sport and tarnishes its best intentions, no matter where or what form the track may take.

Monza is a purpose-built high-speed circuit, established in 1922 in the Royal Park within a suburb of Milan. Monaco is the slowest on the F1 calendar thanks to the racing being constricted by narrow streets that make up arguably the best-known Grand Prix track in the world. The contrast may be stark and the challenge diverse but the end game is the same as it has always been; to finish first and score maximum championship points. Then move on to the next race track. And the one after that.

Variety has always been an essential part of F1’s fabric. The first motoring competitions were staged more than 100 years ago with races from city to city. The inherent danger to spectators brought an awareness of the need for more control in the shape of a circuit that could be more easily managed and provide some form of crowd constraint. That said, public highways and byways continued to provide the easiest, if not the most socially convenient, form of race track, but permanent venues soon became popular and offered more potential for profit.

Nonetheless, when the World Championship was introduced, the seven-race calendar in 1950 was dominated, not by permanent fixtures, but by road and street tracks such as Spa-Francorchamps, Reims, Berne and, of course, Monaco. The diversity presented by these four ensured their presence: Spa utilising nine undulating miles of roads sweeping through the Belgian Ardennes; Reims being a flat and very fast triangle of straight roads amid corn fields to the west of the French city; Berne, a scary and relentless sequence of curves and high-speed corners through woods on the northern outskirts of the Swiss capital; and Monaco has been described above.

By their very nature, all four were bound to cause casualties. But, even allowing for a more relaxed approach to safety in the decade following the Second World War, Berne in particular was considered excessively dangerous. The end of Grand Prix racing in Berne in 1955, however, was not due to the inherent risks but because motor racing was banned in Switzerland following the death of more than eighty spectators that year in the Le Mans 24-Hour sports car race.

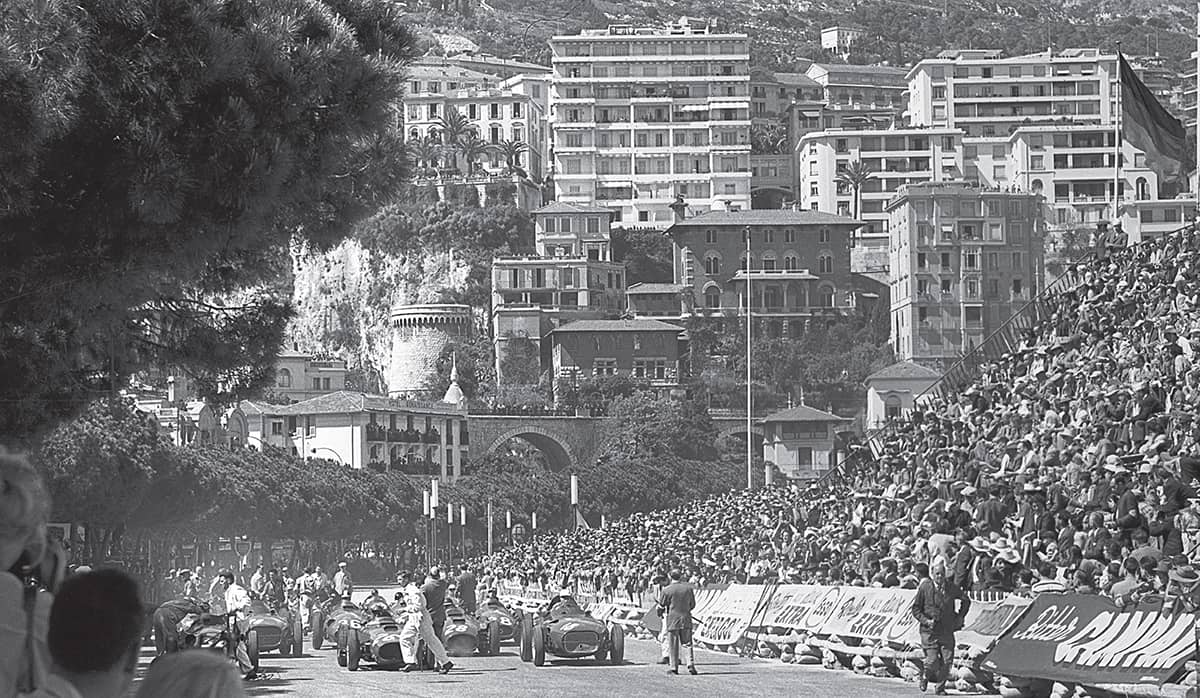

The starting grid at Monaco (shown in 1957) used to be on the straight that is now the pit lane run in the reverse direction.

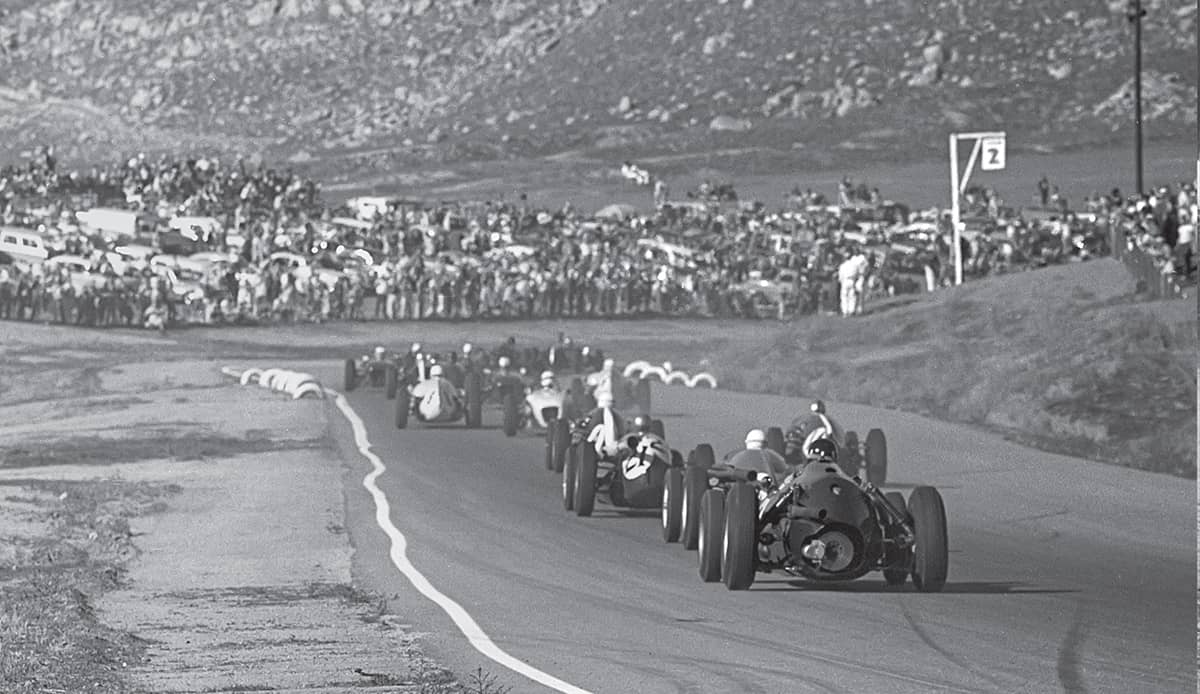

Riverside in California was used just once to stage the United States Grand Prix. The race gets under way in 1960.

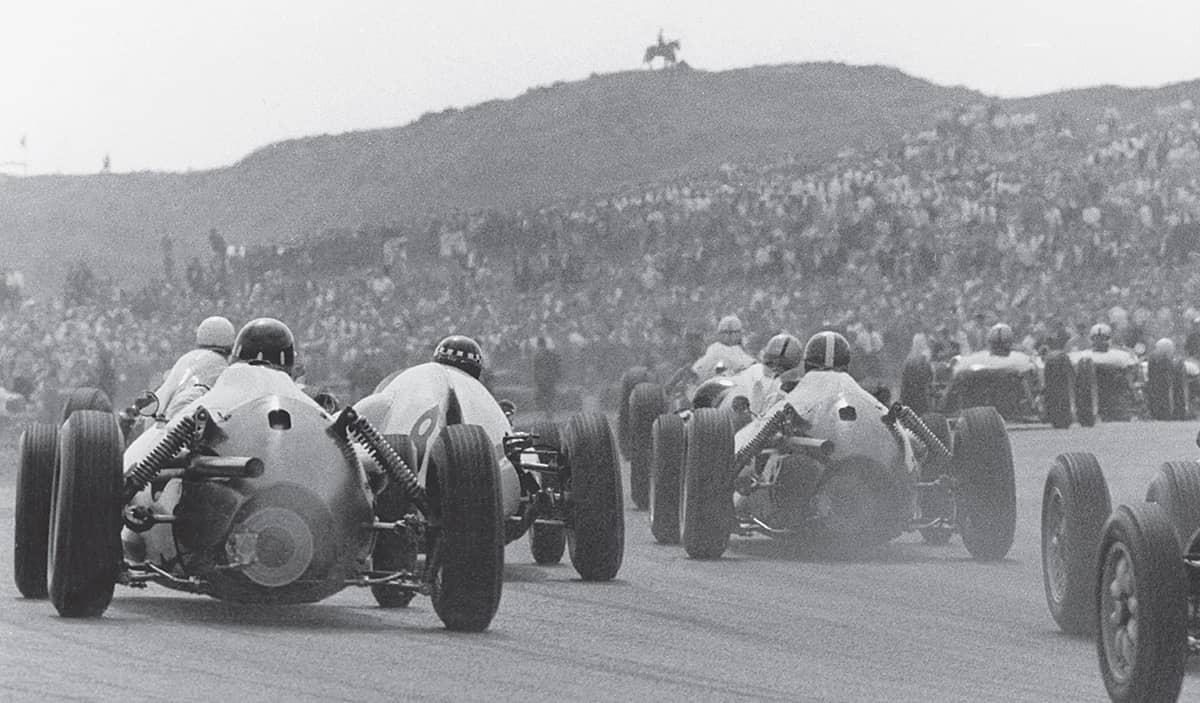

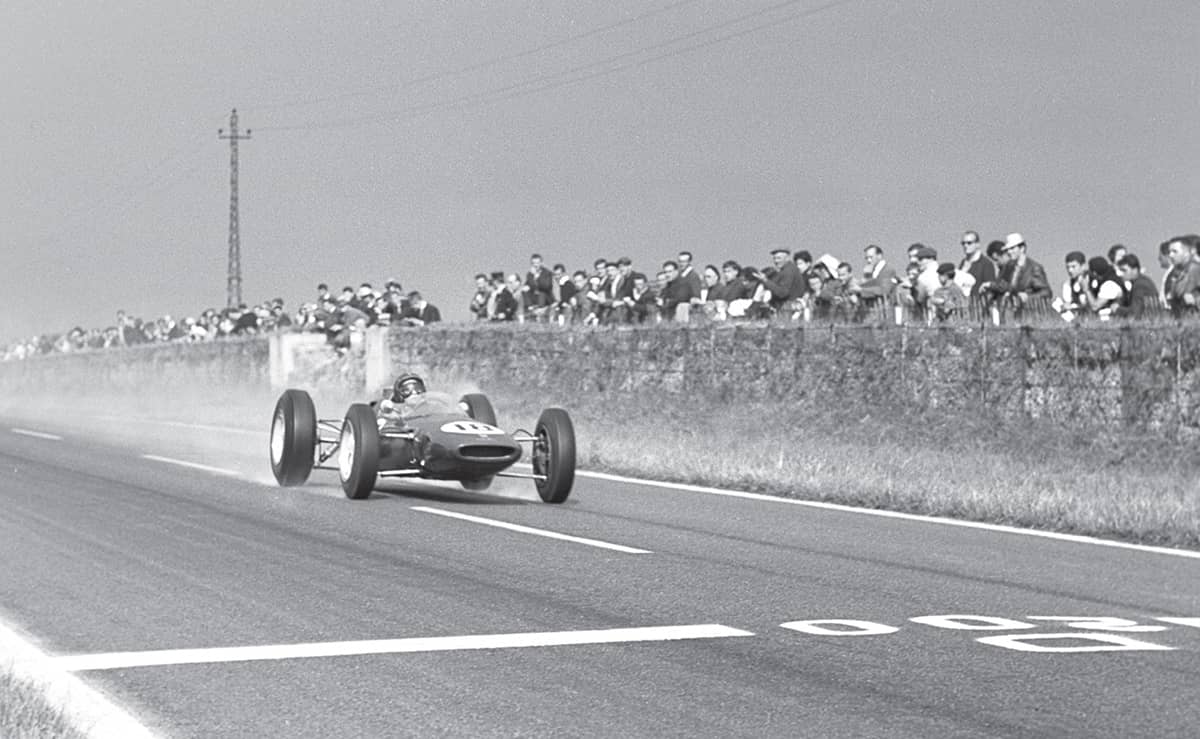

Heading off to the seaside: the first lap of the 1960 Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort.

Spa-Francorchamps in Belgium is notorious for fickle weather. Jim Clark heads for victory with his Lotus-Climax in 1963.

Nigel Mansell sweeps through the exit of Paddock Hill Bend on his way to victory with the Williams-Honda at Brands Hatch in 1985.

Danger was not confined to circuits on public highways passing between trees. The Nürburgring, thought to be one of the greatest race tracks ever built when opened in 1926, was also one of the most hazardous. It could hardly be otherwise given that this leviathan snaked its way through the Eifel mountains for fourteen tortuous miles, with no two of more than 170 corners being the same. Not a year would pass without casualties, the situation made worse by the impossible task of marshalling this giant of a race track.

The same applied, albeit to a lesser degree, through the fast curves of Spa, and yet each track survived through the 1960s, despite a litany of sorrow. This in itself summed up the conflict of emotion that attended such majestic tracks. Paradoxically, the knowledge that an error could be severely punished brought a frisson of excitement as a driver measured up to the challenge of getting through these corners faster than anyone else. They were racing against the track just as much as their competitors.

Under different circumstances because of lower speeds, the same test of daring nevertheless applied to Monaco, where a wheel a fraction out of line would bring instant retirement against a wall or kerb. The wide grassy expanse of Silverstone – a former airfield – this most certainly was not.

It was an immediate means of measuring a driver’s skill and precision – with the added ingredient of maintaining concentration throughout a race lasting, in the 1950s and 1960s, at least, for more than two hours, often in searing heat. The price of the smallest misjudgement could be horrific.

At Monaco in 1967, Lorenzo Bandini was carrying the hopes of Ferrari – and by association, the whole of Italy – as he chased the leader with 19 of the 100 laps remaining. A tiny miscalculation had massive consequences as he clipped the high-speed chicane leading to the harbour front. Thrown from its course, the Ferrari hit straw bales lining the outside of the corner, overturned and caught fire. Even with marshals in close proximity, Bandini could not be extricated and died in hospital days later. There have been no fatalities at Monaco since.

In fact, the sport’s terrible record improved massively as F1 came to terms with the fact that race tracks needed to offer the best possible protection and medical support should a driver crash – not necessarily through any fault of his own. From having close to one fatality every month during the 1968 season, Grands Prix ran for twelve years without tragedy until the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix when two drivers were killed. The fact that one of them was Ayrton Senna, a three-time World Champion and six-time winner at Monaco, brought home the fact that circuits could never be completely safe.

But that has not stopped the search for perfection. If anything, it has accelerated it. The sport’s governing body, the FIA, examines every detail of every accident, fatal or not. Circuits and facilities are improved continuously.

Spa-Francorchamps remains proof that this can be done without compromising the very reason a driver snuggles into the cockpit, has his seat harness pulled painfully tight, closes his visor, grips the wheel and prepares to take on the race track. Spa was heavily revised in 1983 and yet retains much of its original character. It is a place where a hint of sweat on a driver’s brow and a wide-eyed expression says everything about man and machine versus race track. It’s about flirting with danger and embracing triumph. Just as it always was.

Ayrton Senna’s Lotus-Renault charges down the hill at Spa-Francorchamps in 1985 and prepares to tackle Eau Rouge, one of the classic corners in F1.

■ FRANCE

There have been more Grand Prix tracks in France than in any other European country. Reims (Figure 1 and Figure 2) was an obvious choice when the championship was instigated in 1950, the flat triangle of public roads having been used for racing since 1932. Jim Clark and Lotus won in 1963 (Figure 3 and Figure 4), three years before Reims was deemed unsafe because of the extremely high speeds. Rouen, a fast but very different type of road circuit, was first used in 1952 (Ascari’s winning Ferrari pictured Figure 5), the cobbled hairpin being a feature of this picturesque but dangerous track (Fangio’s Maserati negotiates the hairpin Figure 6, on his way to victory in 1957). When introduced to the F1 calendar in 1965, stunning roads around an extinct volcano above Clermont-Ferrand were popular among drivers, if not the mechanics, forced to use a rudimentary paddock. Here you see the March and BRM teams cheek by jowl (see here) in 1970, two years before the final Grand Prix was dominated by Chris Amon’s Matra (see here) until the luckless New Zealander suffered a puncture. A purpose-built circuit at Paul Ricard may have been considered safer when first used in 1971 but the track, high above the Mediterranean coast, produced a spectacular incident in 1989 (see here) when Mauricio Gugelmin misjudged his braking at the first corner and became airborne, the turquoise March wiping off the rear wing from Nigel Mansell’s Ferrari as Thierry Boutsen’s Williams-Renault (number 5) locked a front brake in avoidance. No one was hurt.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

The March and BRM teams cheek by jowl at Clermont-Ferrand in 1970.

Chris Amon’s Matra.

The 1971 purpose built track at Paul Ricard that produced a serious crash in 1989 – fortunately no one was hurt.

■ MONACO

This is the most famous race track in the world, if only because 70 per cent of what you see today was used for the first Grand Prix in 1929. The setting could not be more glamorous, from the steep climb towards the Hotel de Paris and the Casino, to the tunnel and the dash along the waterfront, the entire glittering scene overlooked by the Royal Palace.

The Mercedes of Stirling Moss (6) and Juan Manuel Fangio lead the pack through Gasworks Hairpin, the first corner in 1955.

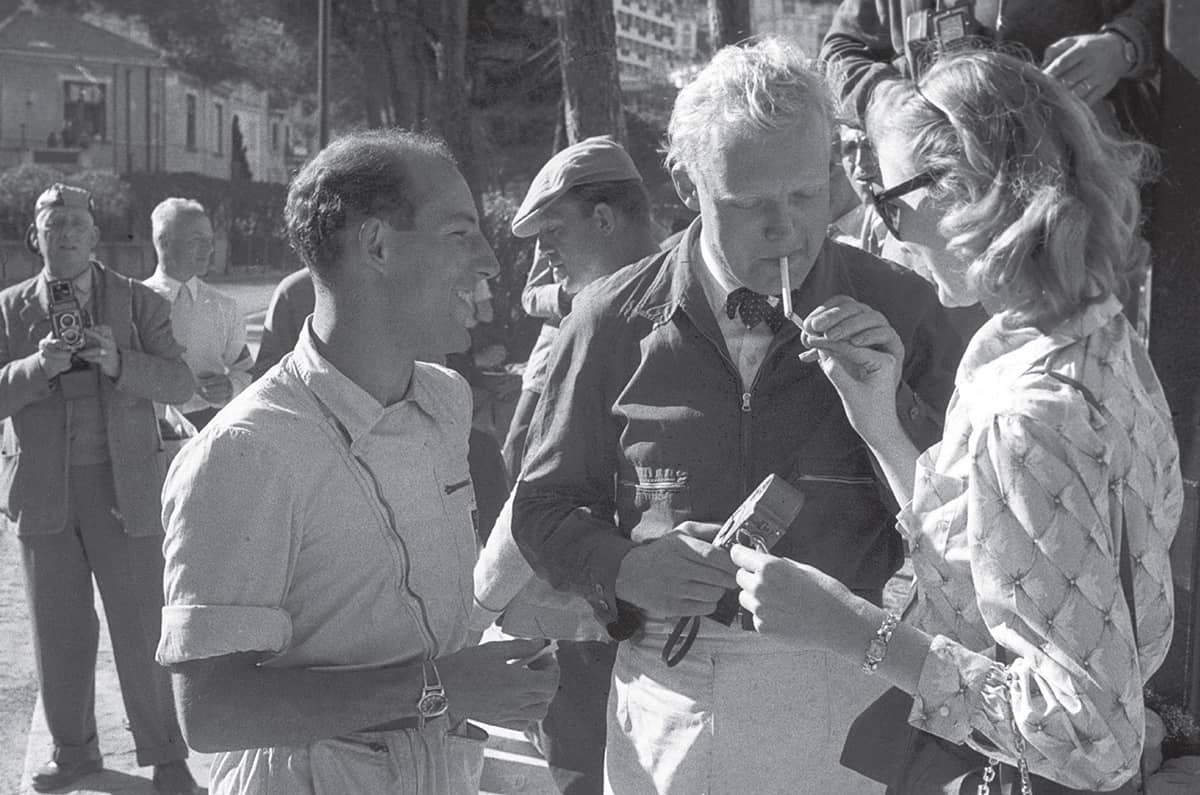

Moss looks on as Mike Hawthorn receives a light.

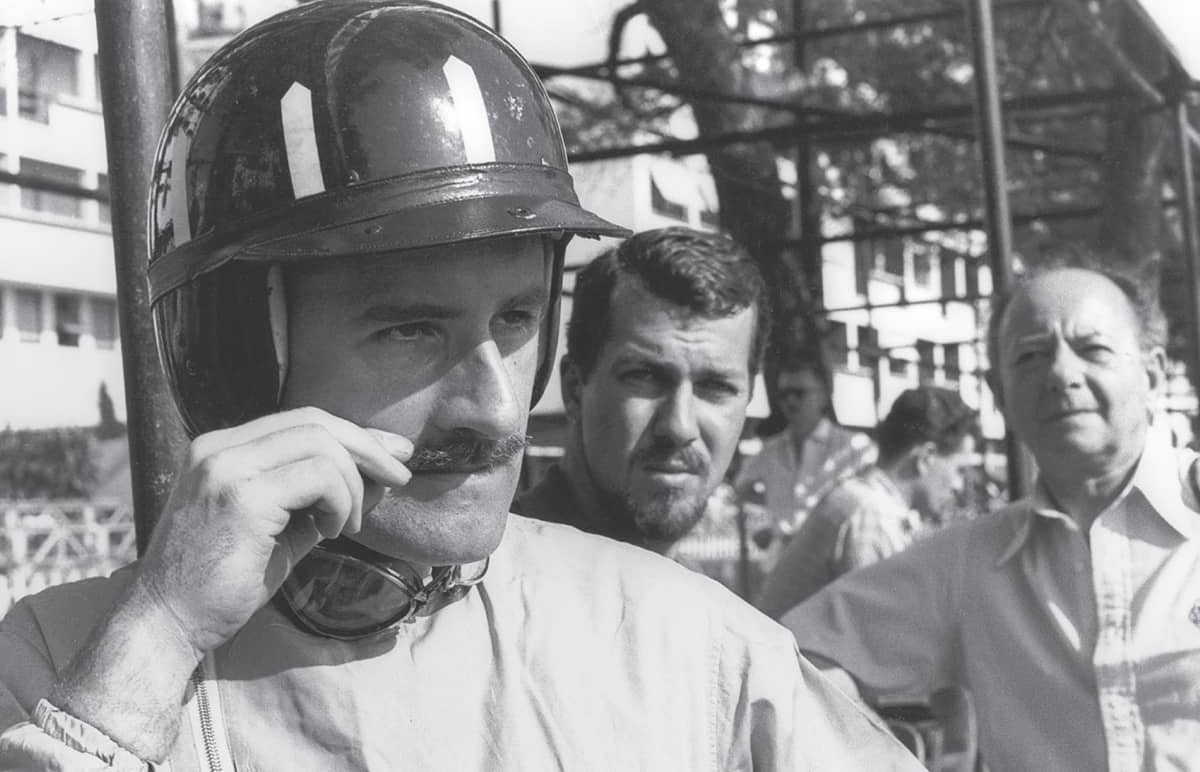

Graham Hill tweaks his famous moustache with the bearded Jo Bonnier and Raymond Mays, the boss of BRM, in the background.

Surtees, Hill and Bandini in 1965.

Jackie Stewart congratulates his BRM team-mate Hill after winning in 1965.

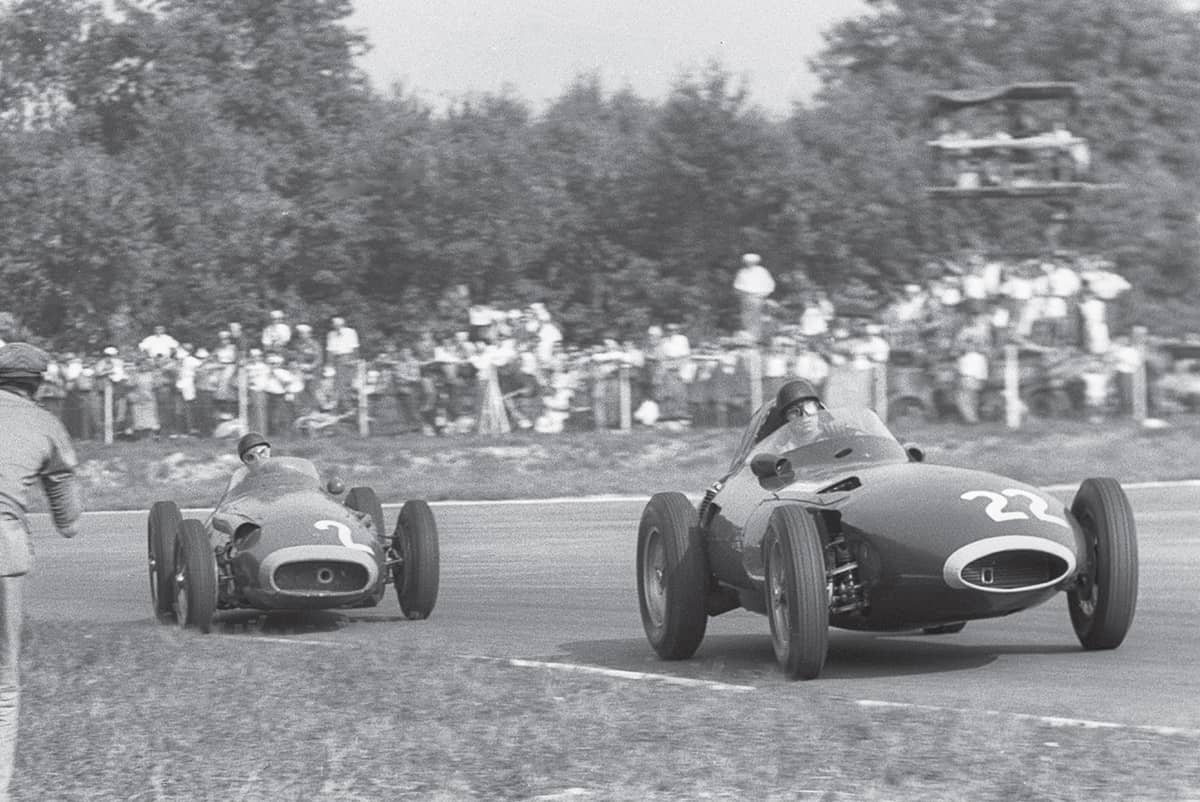

The Maserati (28) of eventual winner Stirling Moss fights with the Ferrari (22) of Eugenio Castellotti from the start in 1956.

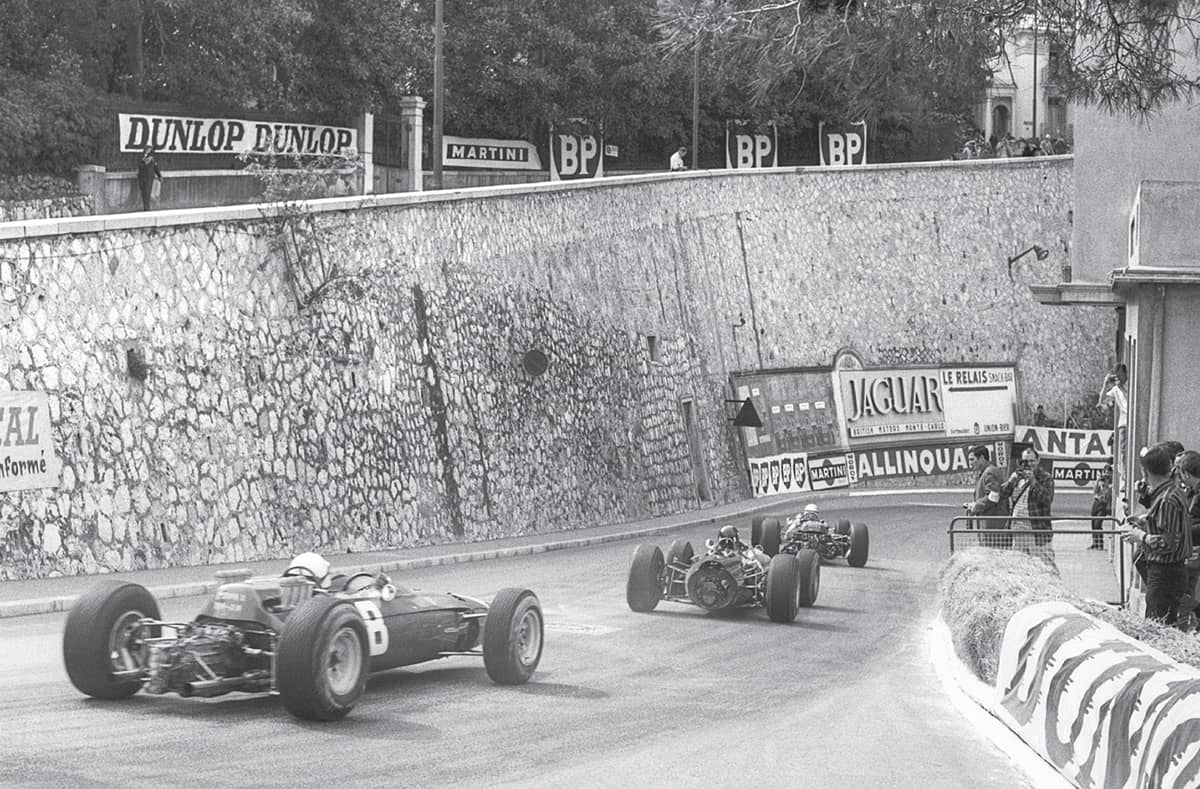

The backdrop may have changed, but the hairpin remains exactly as it was; the Ferraris of Lorenzo Bandini and John Surtees negotiate the tightest corner in F1 in 1965.

Chris Amon’s March leads the Brabham of Jack Brabham, Jacky Ickx’s Ferrari and the Matra of Jean-Pierre Beltoise away from the hairpin in 1970.

Hill’s winning Lotus is parked by the kerb in what was the pit lane in 1968.

The original track was shorter than today, the start and finish area being where the pit lane is presently located. The addition around the swimming pool in 1973 began just after Tabac (above, being negotiated by Luigi Musso’s Ferrari in 1958) and allowed the pits to be removed to safety from the side of the main start and finish straight.

Ayrton Senna’s McLaren-Ford climbs the hill in 1993 on his way to the last of a record six wins at Monaco.

Nico Rosberg points his Mercedes up the hill towards Casino.

David Coulthard won twice in the Principality.

The Williams of Valtteri Bottas kicks up sparks.

Kimi Räikkönen’s Ferrari tackles Tabac in 2015.

■ ITALY

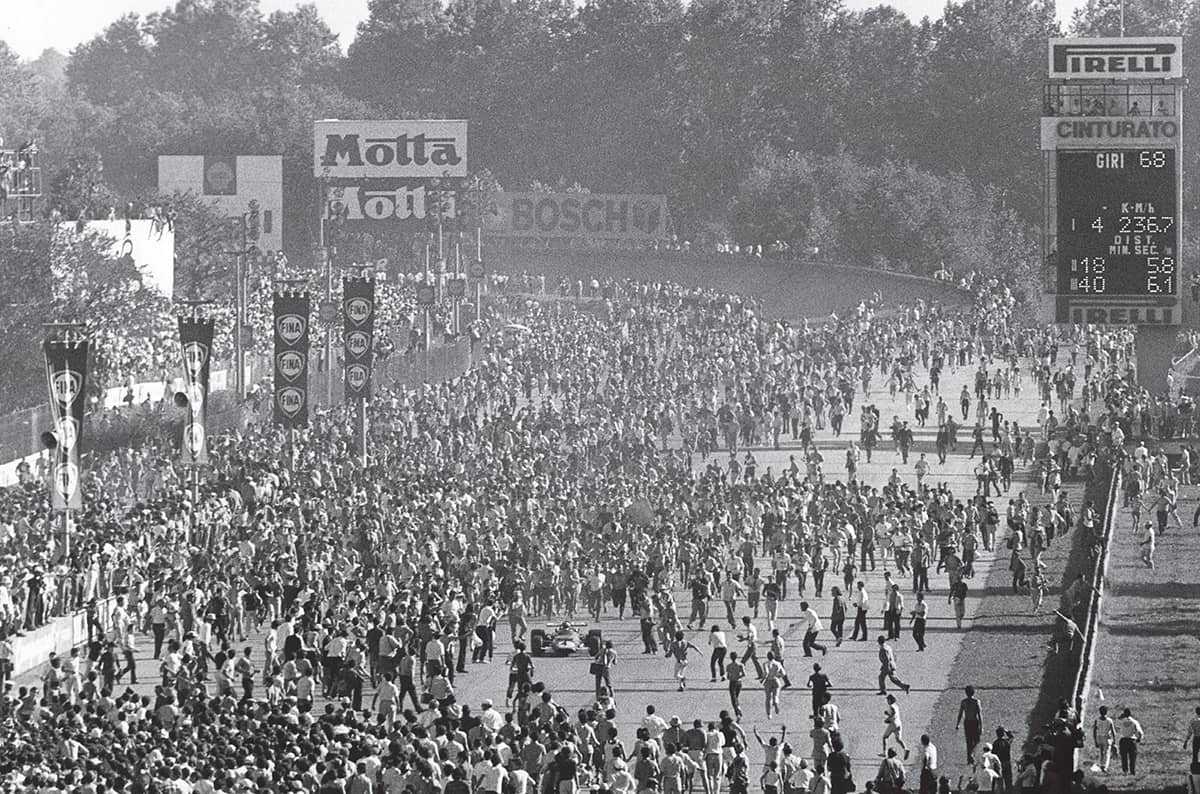

The Italian Grand Prix is all about the madness of Monza, captured perfectly in 1970 as Clay Regazzoni’s winning Ferrari was engulfed as an enthusiastic mob invaded the track (Figure 1), the huge numbers indicating many had actually climbed the fence before the race had finished. This shot also catches the historic sense of the famous autodrome, opened in 1922 with the banking, no longer used, arcing across the background. The flat-out nature of the long straights has produced epic battles with Italian red cars usually in the midst of them.

Figure 1

Juan Manuel Fangio’s Maserati leads the Ferraris of Alberto Ascari and Giuseppe Farina in 1953.

Fangio drifts his Maserati 250F while chasing the Vanwall of Tony Brooks in 1957, the same pair poised on the grid before the start.

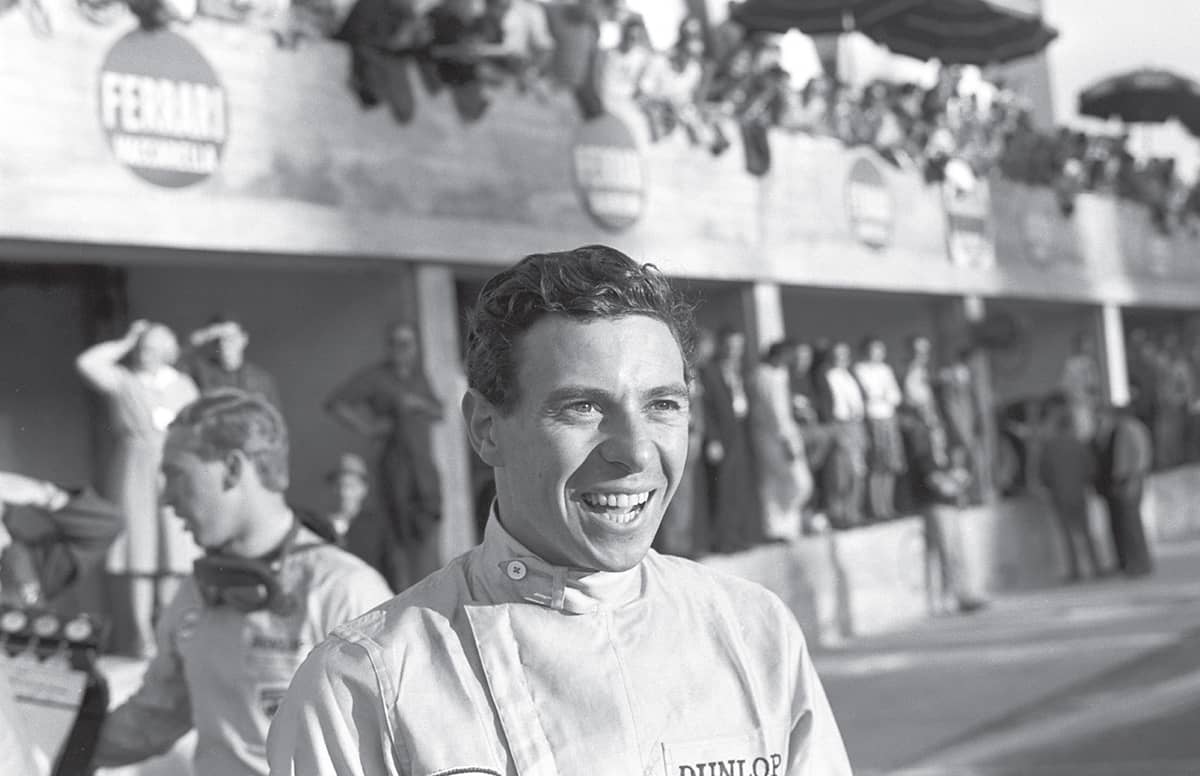

A happy Jim Clark, victor at Monza in 1963.

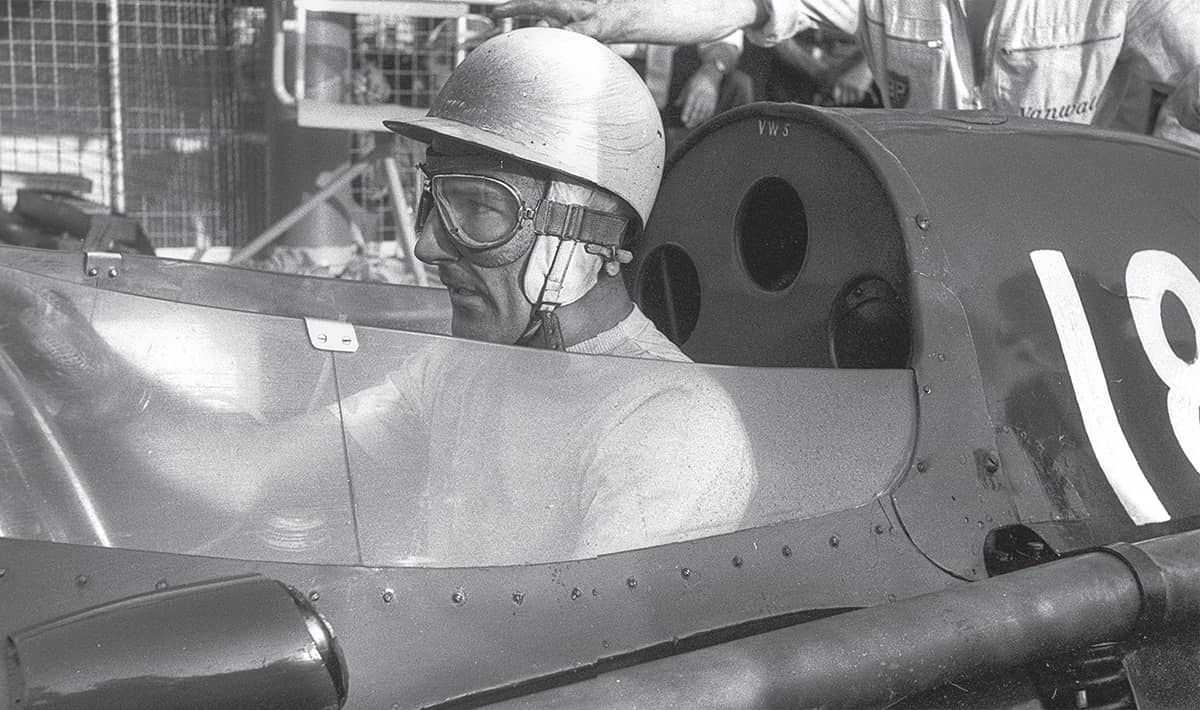

A study in concentration as Stirling Moss prepares to start the same race in his Vanwall.

Sebastian Vettel prepares for the start at Monza in 2015. The emergence of Imola as an alternative saw the Italian Grand Prix shift to the picturesque track in the province of Bologna in 1980 before assuming the title San Marino Grand Prix in 1981.

The atmosphere was no less passionate despite Ferrari not being part of a battle between the McLaren-Hondas of Ayrton Senna and Alain Prost in 1988.

Ferrari adulation at the exit of Imola’s Tosa corner.

There was little in motorsport to match the pulsating atmosphere on the hillside at Imola.

Jenson Button produced stirring performances in the BAR-Honda at Imola.

Sadly, Imola will also be remembered for the death of Senna. Memorabilia in tribute adorns the fence at Tamburello, the corner where the Brazilian’s Williams-Renault crashed on 1 May 1994.

Michael Schumacher brought joy to the home crowd with no fewer than six wins for Ferrari.

■ HOLLAND

The seaside track at Zandvoort was hugely popular from the moment it hosted the first Dutch Grand Prix in 1952, the sand dunes forming excellent viewing points. Located a train ride from Amsterdam, the race became a regular feature of the F1 calendar and attracted spectators from France, Belgium and Germany, as well as from across the English Channel. British fans were thrilled to witness James Hunt score his first Grand Prix win after his Hesketh-Ford held off Niki Lauda’s Ferrari in 1975. The long main straight, illustrated in the start shot from 1965 (Figure 1), contributed to close racing as cars braked heavily for the first corner. In 1966 Jack Brabham led Jim Clark away from that corner (Figure 2). Twelve years later, Mario Andretti and Lotus team-mate Ronnie Peterson dominated the race, 1985 providing a livelier Grand Prix as Alain Prost (Figure 3) battled with his McLaren team-mate Niki Lauda. René Arnoux’s Renault led the field at the start in 1980 (bottom, right).

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

■ PORTUGAL

Jim Clark’s set expression (Figure 1) summed up a rare driving error as the Scotsman walked away from his damaged Lotus in Porto in 1960. Attempting to take the first corner flat out during practice while avoiding the tramlines that were part of the street circuit, Clark clipped a kerb and spun into the straw bales. The car was patched up and Clark went on to score his first podium finish the next day. The street circuit, with its mixed surfaces and cobblestones, was only used twice, one more time than a road circuit at Monsanto near Lisbon where Dan Gurney is pictured (Figure 2) in his Ferrari on his way to third place in 1959. Portugal would be without a Grand Prix until the upgrading of Estoril in 1984. This permanent track would stage thirteen Grands Prix and prove popular for testing.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Niki Lauda raises an arm in triumph at Estoril in 1984, second place being good enough to give the McLaren driver the championship by half a point.

The Benettons of Alessandro Nannini and Thierry Boutsen are prepared in the cramped garages in 1988.

Gerhard Berger’s Ferrari raises sparks on the narrow and bumpy main straight in 1989.

■ HUNGARY

F1’s first venture into an Eastern bloc country in 1986 saw the introduction of the Hungarian Grand Prix at the Hungaroring. The purpose-built track was tight and twisting, the only overtaking place of note being into the first corner, where the Ferraris of Rubens Barrichello and Michael Schumacher led the Williams-BMW of Ralf Schumacher in 2002 (Figure 1). Although the races tend to be processional, the Hungaroring has set statistical landmarks by settling the championship twice (Nigel Mansell in 1992 and Michael Schumacher 2001) as well as listing several first-time winners (Damon Hill in 1993, Fernando Alonso in 2003, Jenson Button in 2006 and Heikki Kovalainen in 2008).

Figure 1

■ GERMANY

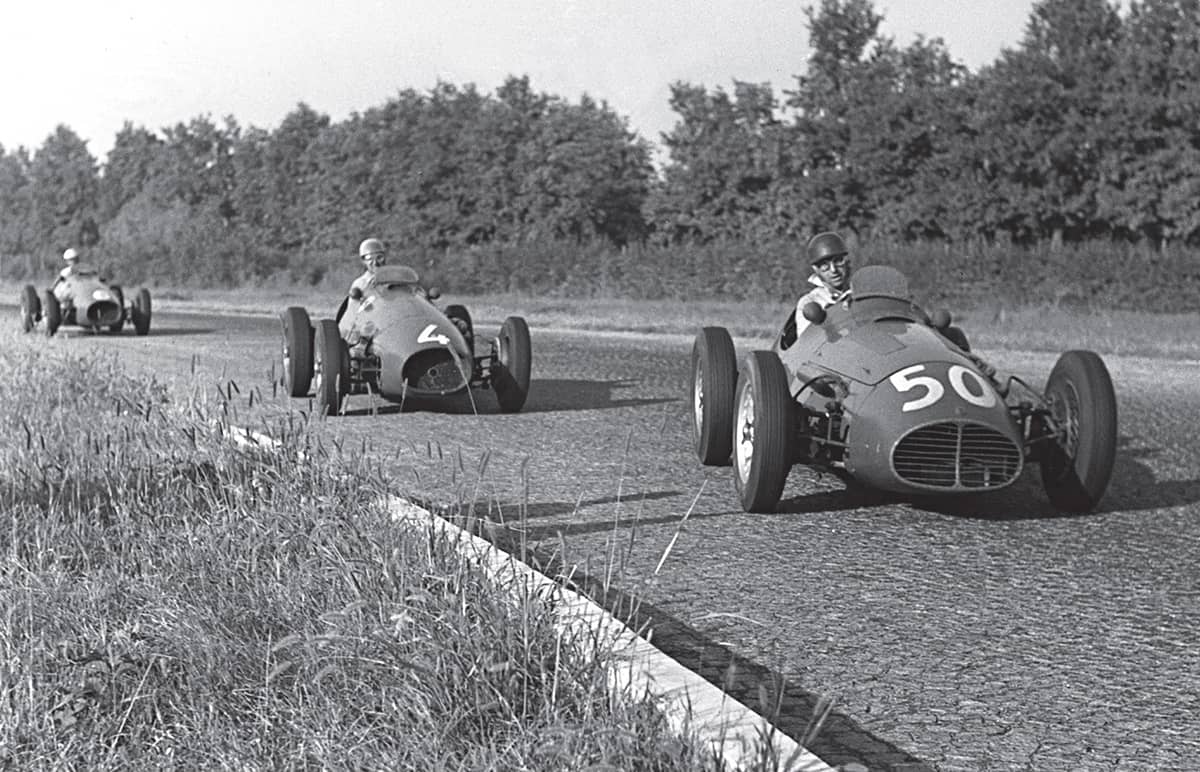

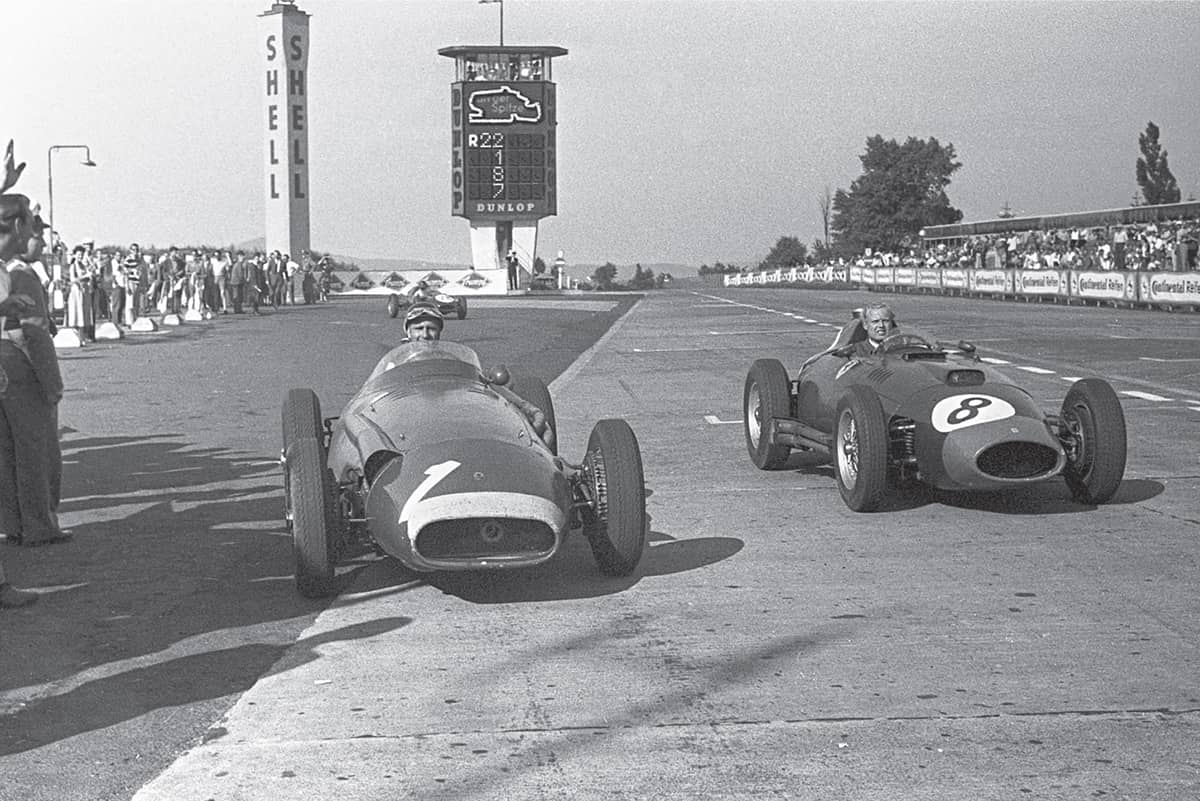

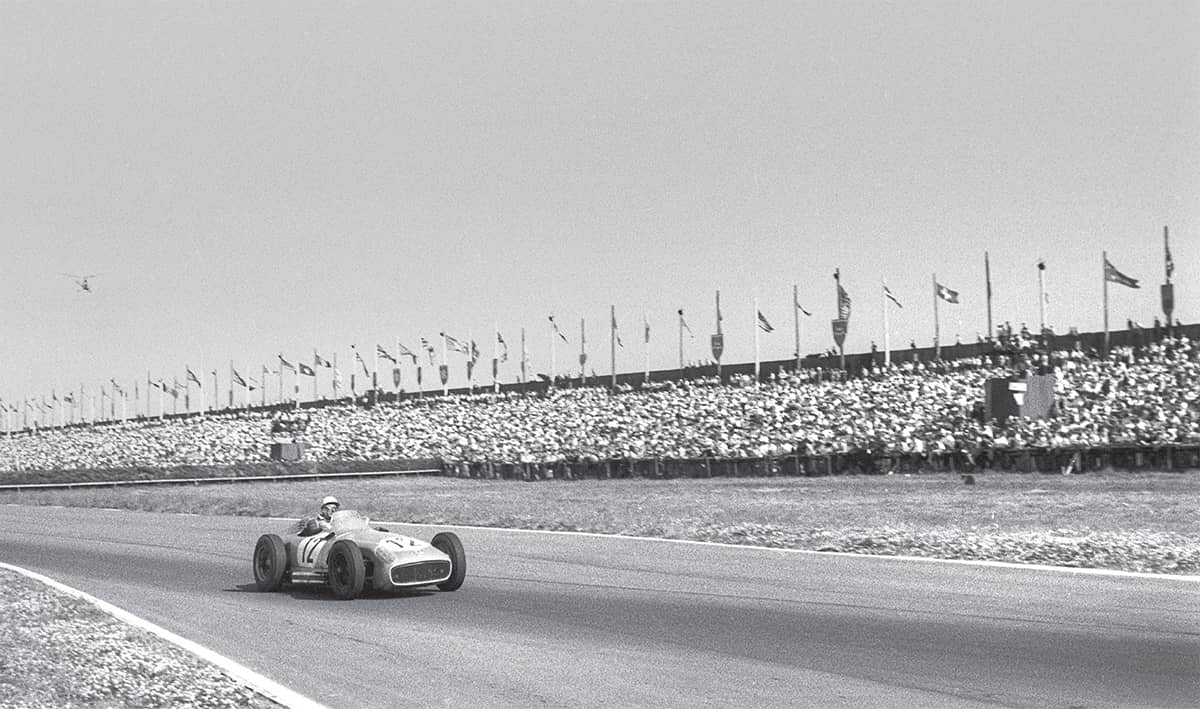

The German Grand Prix has been staged on four different circuits, none more infamous than the Nürburgring Nordschleife, twisting and turning for fourteen miles through the Eifel mountains. Opened in 1926, the circuit joined the World Championship trail in 1951 and remained on it until deemed too dangerous following Niki Lauda’s near-fatal crash in 1976. In 1957 the race produced one of the most mesmeric performances of all when Juan Manuel Fangio (Figure 1) chased, caught and overtook the Ferraris of Peter Collins and Mike Hawthorn after making a pit stop. Fangio posed in his Maserati (number 1) alongside Hawthorn’s Ferrari (Figure 2) before the start. The field gets away in 1956 (Figure 3) and John Surtees takes his first Grand Prix victory for Ferrari in 1963 (Figure 4).

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Jim Clark (1) leads Graham Hill’s BRM into the first corner of the 1965 Grand Prix.

Clark going on to win, his Lotus-Climax casting a shadow in 1964 as the circuit weaves its way through the forest.

When the Nordschleife fell from favour, and before a new track was built alongside, the Grand Prix moved to Hockenheim, where Rubens Barrichello scored an emotional maiden victory in his Ferrari in 2000.

■ SPAIN

Spain has been part of F1’s fabric since the early days with no fewer than six different tracks staging the Grand Prix. Jarama, used nine times between 1968 and 1981 (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3), was arguably the least popular, the 1970 race being marred by a fire when two cars collided, leaving victory to the blue March of Jackie Stewart. Gilles Villeneuve scored a spectacular and unexpected win in 1981 when he managed to withstand huge pressure and hold everyone back with the cumbersome Ferrari (number 27). Jerez (Figure 4; Figure 5) was used seven times between 1986 and 1997 before the Spanish race found a more permanent home outside Barcelona at Circuit de Catalunya. The Williams-Renault of Nigel Mansell and Ayrton Senna’s McLaren-Honda engaged in an epic wheel-to-wheel contest at the first race in 1991 (above). McLaren’s Lewis Hamilton and Fernando Alonso (Figure 6) sprayed the champagne after finishing second and third in 2007, with happier times for the home hero as Alonso greeted his fans after winning for Ferrari in 2013 (Figure 7).

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

■ BELGIUM

Despite ten visits to Zolder, Spa-Francorchamps is considered to be the spiritual home of the Belgian Grand Prix. The awesome circuit in the Ardennes was first used for a Grand Prix in 1925, its nine-mile length causing havoc in 1966 when the race started in the dry and competitors ran into a rainstorm a quarter of the way round the first lap. It was wet for the start in 1965 (opposite bottom left) as the field left the downhill grid and headed into Eau Rouge before the steep, curving climb through the trees towards Les Combes. The Ferraris of Phil Hill and Ricardo Rodriguez fight it out in 1962 (Figure 1). The Cooper-Maserati of Jo Siffert crests the rise at Eau Rouge in 1967 (Figure 2). Spa had become the fastest road circuit in use by 1960 when two British drivers were killed in separate accidents. Growing concern over safety brought a halt to Spa’s inclusion on the calendar after the 1970 Grand Prix, but a first-rate piece of modernisation saw the race return in 1983. The circuit had virtually been cut in half but the atmosphere and challenge remained, particularly the swoop through Eau Rouge. The climb to Les Combes (above) had been straightened to allow speeds approaching 200 mph, contributing to Spa’s continuing reputation as a fast and demanding track. Nigel Mansell (top, right), heads back to the pits after retiring in 1991.

Figure 1

Figure 2

■ JAPAN

Japan has used three circuits: Suzuka, Mount Fuji and Aida. Suzuka stands head and shoulders above not only the other two Japanese venues but just about every other race track on the F1 calendar. It is unique in being the only figure-of-eight layout in Grand Prix racing thanks to a design generated in the early 1960s, one that made Suzuka a fascinating and difficult proposition for the drivers when the Grand Prix arrived in 1987. By comparison, Fuji is relatively simple and was used in 1976 and 1977, the first visit being famous for settling a season-long championship battle between James Hunt and Niki Lauda during a race run in atrocious conditions. There was heavy rain when the Grand Prix returned in 2007 (Figure 1), the following year being the final visit to Fuji before it reverted to Suzuka. Being at or near the end of the season, Suzuka has seen the crowning of several champions, often under controversial circumstances, none more so than in 1990 when Alain Prost and Ayrton Senna collided at the first corner (top, right). Nigel Mansell and Williams team-mate Riccardo Patrese (6) run neck-and-neck into the first corner in 1992 (bottom, right), Mansell having gone off at the same corner in 1991 (bottom, left). Mansell’s Williams chases the Ferrari of Jean Alesi in 1994 (Figure 2). Mika Hakkinen wins the championship for McLaren in 1998 (Figure 3).

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

■ CANADA

Canada has hosted a round of the championship since 1967, starting with Mosport Park and moving to Saint-Jovite the following year, where it ran twice. The race stayed at Mosport until 1977, by which time a new venue on a man-made island in the Saint Lawrence River was ready to become the permanent home for the Canadian Grand Prix. Despite a flat and straightforward profile, the Circuit Gilles Villeneuve (named after Canada’s favourite motor racing son) is a tough proposition, mistakes being punished by the close proximity of concrete walls. It is a popular venue thanks to its location close by the city of Montreal and a knowledgeable and enthusiastic crowd. Originally placed at the end of the season, Montreal settled the championship in favour of Alan Jones in 1980, but a move to the summer months was favoured because of better weather conditions.

The Benetton of Michael Schumacher (right) leads Damon Hill’s Williams (left) into the first corner during their championship battle in 1995.

Montreal was the scene of Lewis Hamilton’s first Grand Prix win in 2007, and another victory in 2012. In 2005, Kimi Räikkönen took his only victory in Canada, the McLaren driver finishing ahead of Ferrari’s Michael Schumacher (next image).

■ AUSTRIA

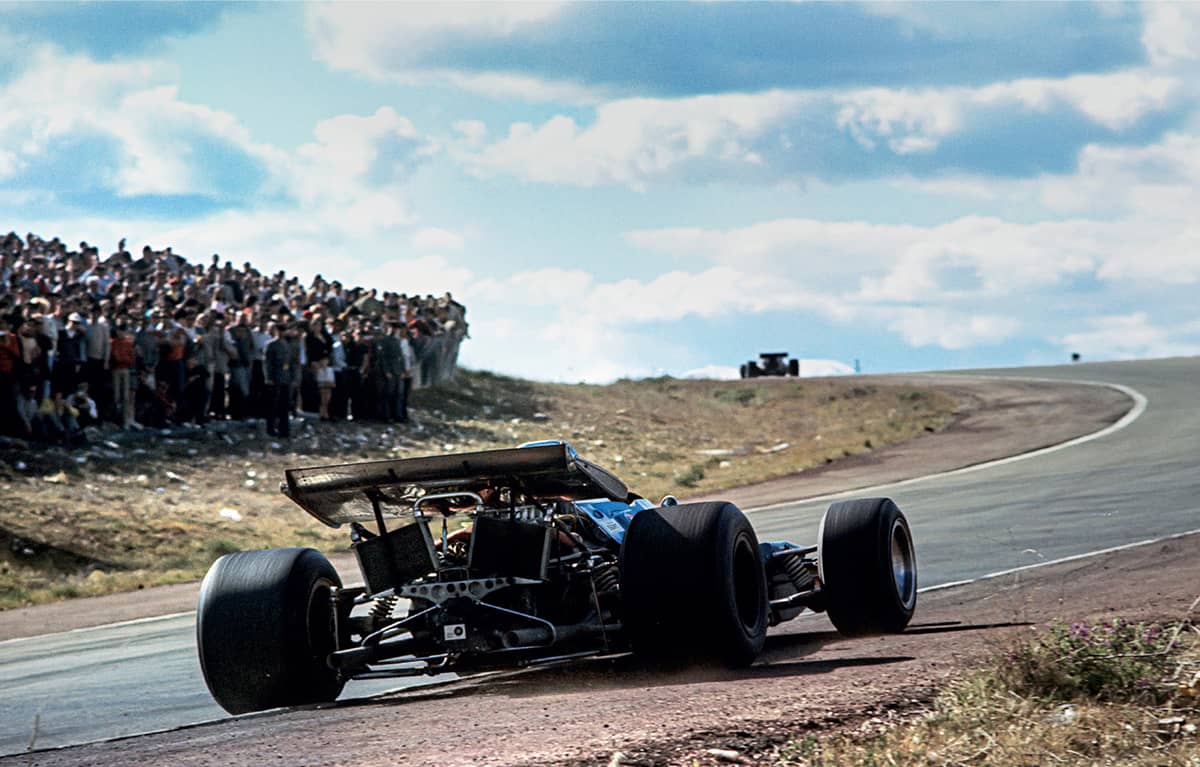

A simple but fiercely bumpy airfield track at Zeltweg provided a spartan venue for Austria’s first championship Grand Prix in 1964. The circuit was never used again and when a brand new track was built in the foothills overlooking the airfield, the comparison could not have been more dramatic. Ready for a Grand Prix in 1970, the Österreichring was a magnificent collection of fast, sweeping curves making full use of the natural majesty of its surroundings in Styria. Thousands of spectators from across the Italian border enjoyed a dream result when Jacky Ickx and Clay Regazzoni finished first and second for Ferrari. Eighteen Grands Prix were staged here until the track was considered too remote a location and out of step with the changing commercial requirements of F1. The average speed had risen to more than 150 mph and concern had grown over the lack of run-off at quick corners such as the Bosch Kurve (Figure 1). A ten-car pile up on the narrow pit straight at the start of the race in 1987 added to the pressure to have the race removed from the calendar. The Grand Prix returned ten years later to a shortened track known as the A1-Ring, where the race was staged until 2003 and included two wins for Michael Schumacher (Figure 2). After much debate over future plans, the site was bought by Red Bull and upgraded in readiness for a round of the championship in 2014.

Figure 1

Figure 2

■ MEXICO

A passion for motorsport in Mexico was answered in 1961 by the building of an impressive track within Magdalena Mixhuca, a municipal park in the suburbs of Mexico City. Granted a round of the World Championship in 1963, the race soon established itself as a welcome part of the calendar (Figure 1: Jo Siffert takes his Lotus-BRM to ninth place in 1963). The Mexican Grand Prix settled the championship in favour of John Surtees in 1964 and Graham Hill in 1968. Hill led Chris Amon’s Ferrari on the first lap in 1967, but victory would go to Hill’s Lotus team-mate, Jim Clark, lying third behind Amon (Figure 2). The previous year’s race was won by the Cooper-Maserati of Surtees, seen leading Jack Brabham’s crossed-up Brabham-Repco at the hairpin (Figure 3). The Mexican race would not be without its controversy, particularly in 1970 when the overenthusiastic crowd encroached onto the edge of the track and a large dog was fatally hit by Jackie Stewart’s Tyrrell. Removed from the calendar, the race was revived on a shorter version of the track between 1986 and 1992, returning once more with further revisions in 2015.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

■ BRAZIL

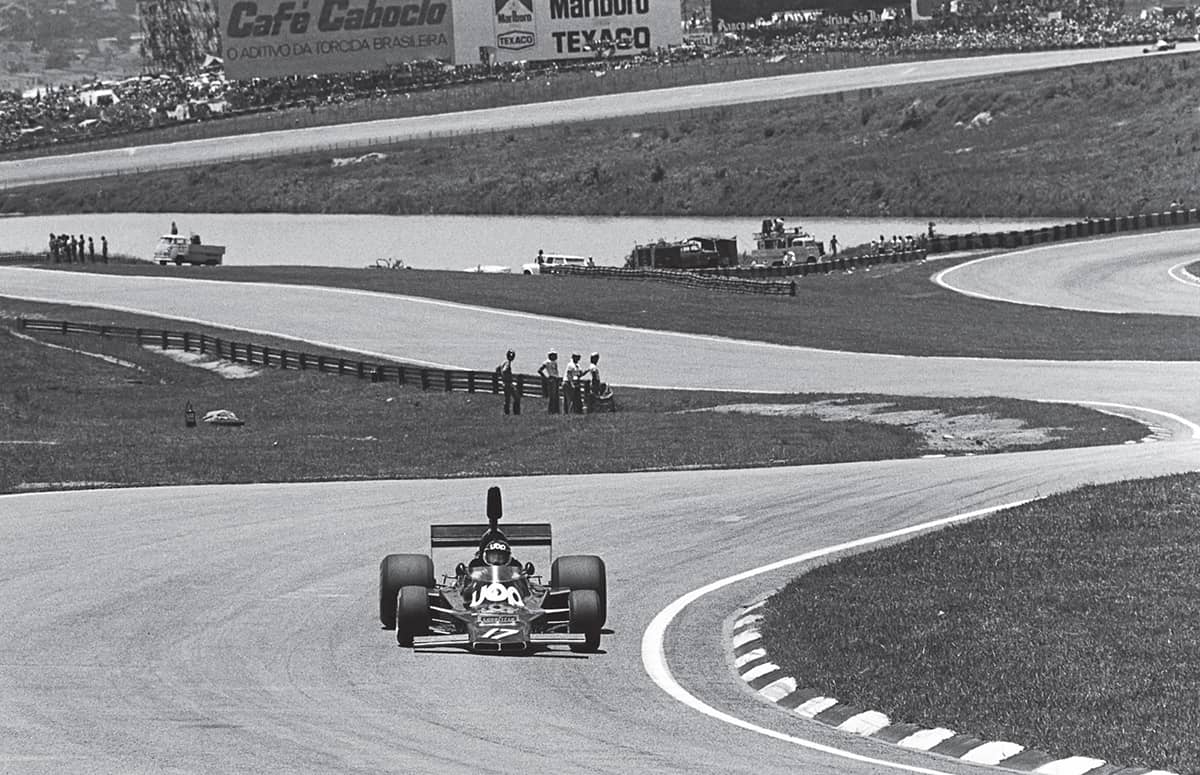

The emergence of Emerson Fittipaldi as Brazil’s first World Champion in 1972 accelerated the desire to stage a Grand Prix in his home country. The obvious choice was Interlagos, a permanent track opened in 1940 and twisting and turning within itself on land on the edge of Sāo Paulo’s sprawling southwest suburbs (Figure 1, Jean-Pierre Jarier’s Shadow-Ford in 1975). Appropriately, Fittipaldi’s Lotus-Ford won the first championship Grand Prix in 1973, Interlagos staging the race until 1980, by which time it was deemed to be too bumpy and dangerous. Jacarepaguá (p.252, top row, left), a new track near Rio de Janeiro, was favoured from 1981 until the rise of Ayrton Senna from Sāo Paulo prompted a major facelift at Interlagos in readiness for a return in 1990. The circuit length had been reduced by almost half but the huge enthusiasm of the Brazilian fans remained and often needed cooling down in the torpid heat of race day (Figure 2). Passion would run even higher if a Brazilian driver was in the reckoning, as was the case when Felipe Massa (p.252, bottom right, and p.253) fought with Lewis Hamilton for the title in 2008, only to lose on the final lap.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Nigel Mansell heads for a surprise victory for Ferrari at Rio de Janeiro in 1989.

The Williams of Damon Hill (left) sits it out with Rubens Barrichello’s Jordan into the first corner of the 1996 Brazilian Grand Prix at Interlagos.

Michael Schumacher blasts his Ferrari away from the pit box at Interlagos in 1999.

Felipe Massa savours the home support after winning the 2006 Brazilian Grand Prix for Ferrari.

Kimi Raikkonen celebrates winning the world title at the final race of the 2007 season at Interlagos.

■ MALAYSIA

A desire to promote Malaysia as an international force led to the construction of a 3.4-mile track at Sepang, close by a new airport serving Kuala Lumpur. Costing 12 million US dollars, the venue was well received when the F1 teams arrived for the first Grand Prix in 1999. The track utilised the rolling landscape to include corners of every type and two wide straights with tight turns at the end of each to encourage overtaking. The first corner was unique in that it turned in on itself initially and offered drivers different lines to help promote close racing. Apart from the G-forces generated by several of the quick corners, drivers had to cope with high levels of humidity, making this one of the toughest races on the calendar.

Sebastian Vettel leads the Ferraris of Fernando Alonso and Felipe Massa at the start in 2013.

■ SWITZERLAND

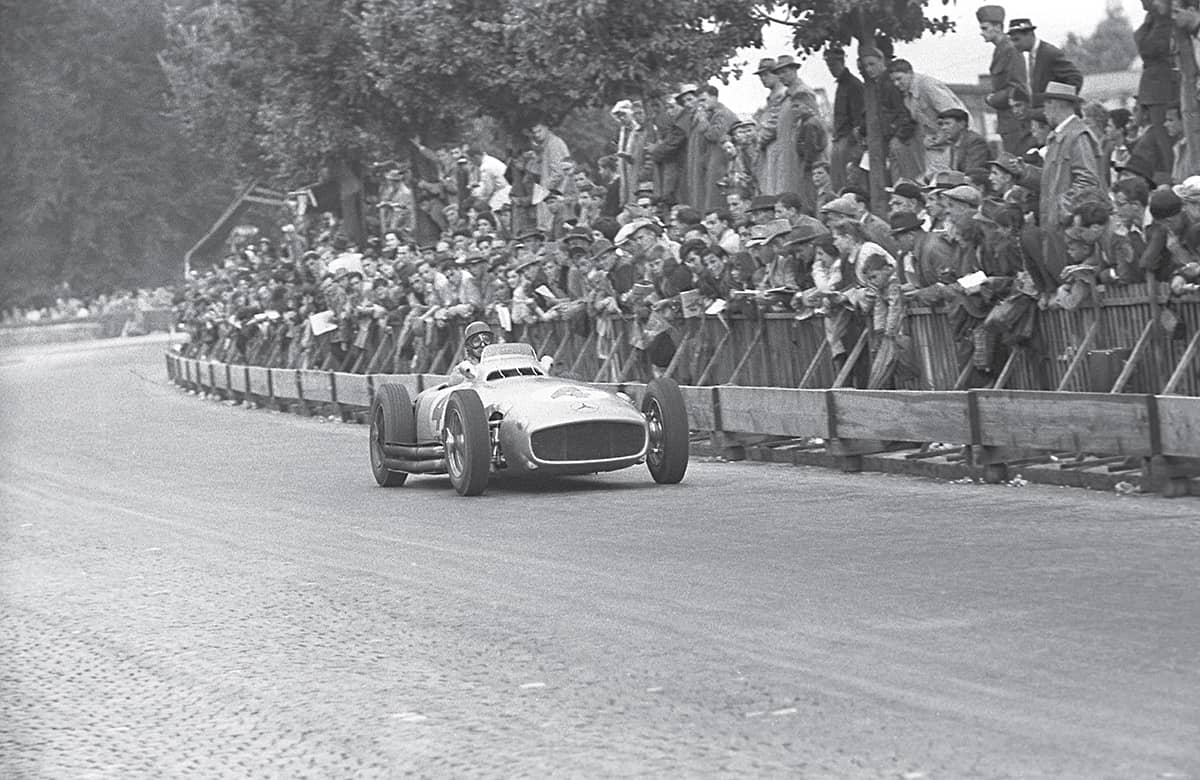

Switzerland’s history of Grand Prix tracks is a slim volume thanks largely to motor racing being banned within the country’s borders following the death of more than eighty spectators during the 1955 Le Mans 24-Hour race. The one track the country had used to stage five championship Grands Prix between 1950 and 1954 was also deemed too dangerous. The Bremgarten circuit was made up of roads running through a forest on the northern edge of Berne. With no straights worthy of the name, the 4.5-mile track formed a relentless series of curves and high-speed corners made even more difficult by constant changes of surface that would become treacherous in the wet. Add the close proximity of trees on both sides of a track with an average speed of around 100 mph and it was no surprise to find fatalities were common. The final race in 1954 was won by the Mercedes of Juan Manuel Fangio (below), the rudimentary crowd safety arrangements clearly shown. The title ‘Swiss Grand Prix’ was given to a round of the World Championship at Dijon in France in 1982, the French Grand Prix having been run at Paul Ricard earlier that year.

■ UNITED KINGDOM

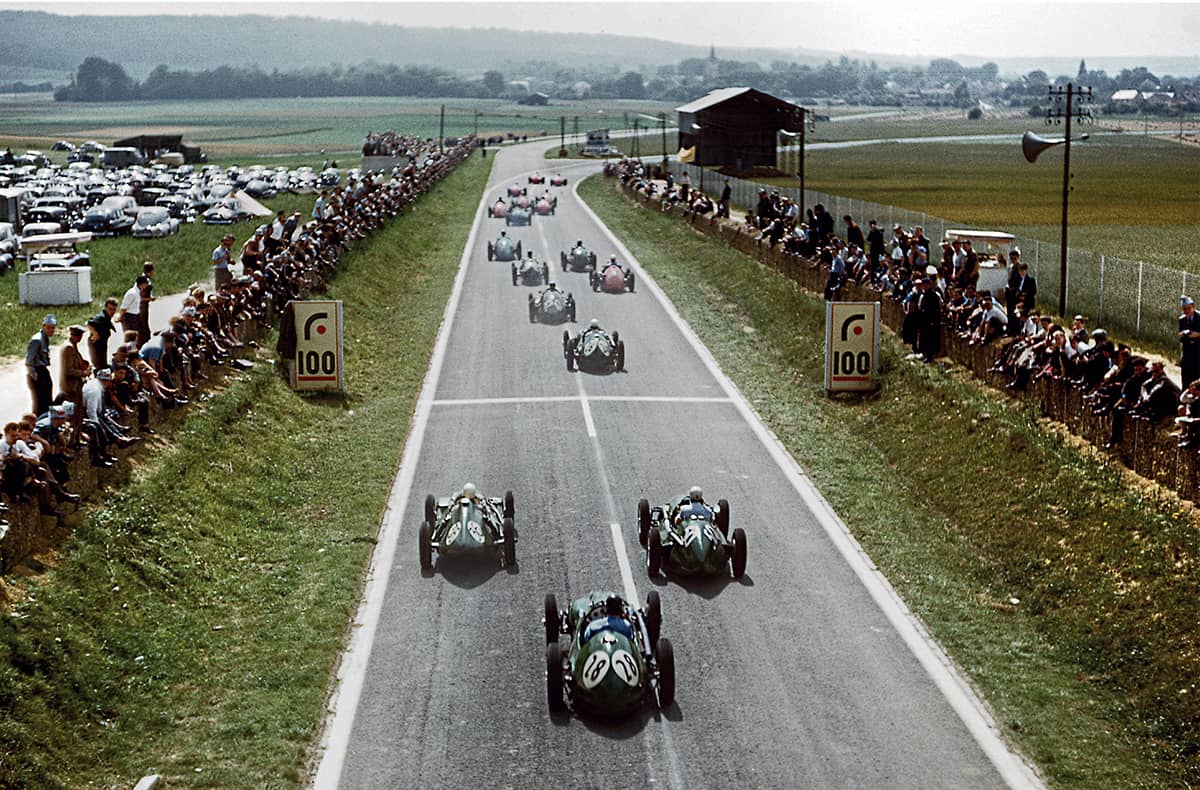

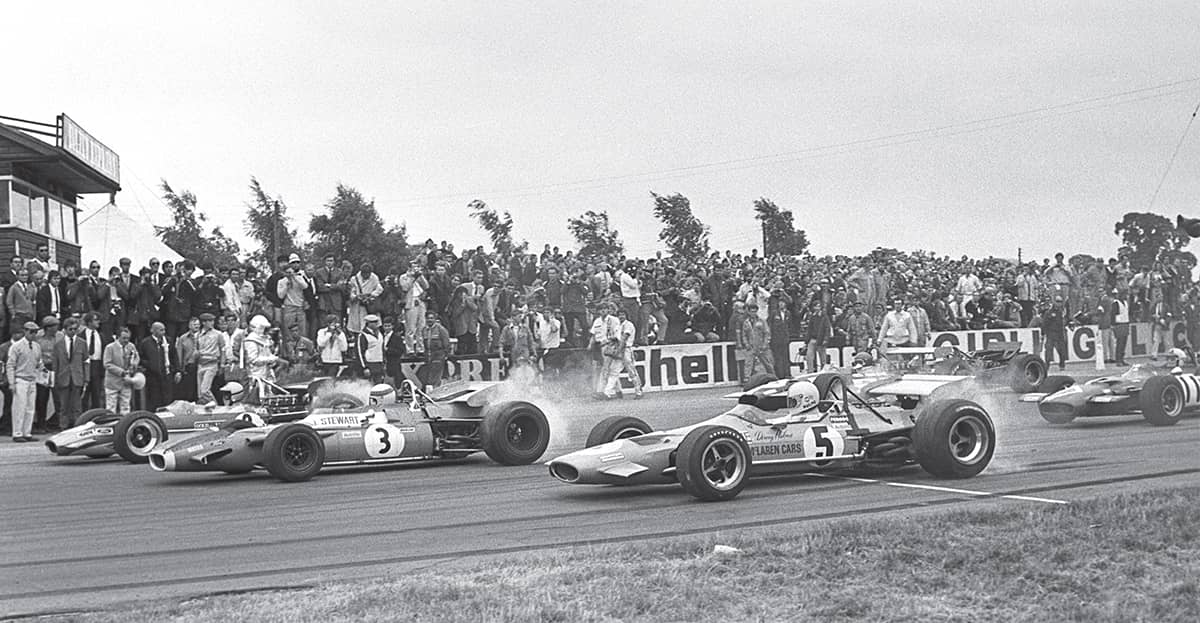

Chosen as the first-ever round of the World Championship in 1950, the British Grand Prix has been a kingpin in the series, never failing to host a round, with Silverstone being the constant throughout. Aintree was the first alternative, the roads around the famous Grand National horse race course being used five times between 1955 and 1962. Stirling Moss scored his first Grand Prix win driving for Mercedes in 1955 (Figure 1), the sun shining that day, unlike the wet 1961 race (Figure 2) as the field lined up in view of Aintree’s imposing grandstands. Juan Manuel Fangio (Figure 3) won the British Grand Prix once and finished a close second to Moss in 1955. One of the greatest contests occurred at Silverstone in 1969 (Figure 4) as the Lotus-Ford of Jochen Rindt and Jackie Stewart’s Tyrrell-Ford (number 3) blasted off the line at the start of a wheel-to-wheel tussle that would last for over an hour, the pair lapping the field, including the McLaren-Ford of Denny Hulme (number 5).

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Jack Brabham won the British Grand Prix for Cooper at Aintree on his way to the first World Championship for a rear-engine car in 1959.

Donington Park hosted a championship round just once, the 1993 European Grand Prix being memorable for a stunning drive by Ayrton Senna. The Brazilian’s McLaren-Ford lay fourth behind the Williams-Renaults of Alain Prost and Damon Hill and Karl Wendlinger’s Sauber not long after the start of the opening lap. Senna would be leading at the end of it.

Brands Hatch hosted the race fourteen times, starting in 1964 and including 1986 (Nelson Piquet’s Williams-Honda leads the pack through Paddock Hill Bend).

■ UNITED STATES

With no fewer than ten different venues since 1959, the United States Grand Prix has tried everything from permanent tracks to street circuits and an adaption of the famous Indianapolis 500 oval. Following brief visits to Sebring in Florida and Riverside in California, Watkins Glen became the most successful, the purpose-built track in New York State being used twenty times before it was no longer considered suitable in 1981. In 1982, there were three Grands Prix in the USA: on the streets of Long Beach and in a converted car park in Las Vegas in the west, and in downtown Detroit (Figure 1), a street circuit that went on to host the US Grand Prix East seven times. For various reasons – mainly finance and an inability to meet required standards – all three faded, to be replaced by unsuccessful attempts on the streets of Phoenix and Dallas. Indianapolis, never totally satisfactory, lasted for eight years until, finally, a brand new circuit near Austin in Texas appeared to answer all the questions when introduced in 2012, the race being won by the McLaren-Mercedes of Lewis Hamilton (Figure 2).

Figure 1

Figure 2

■ AUSTRALIA

Grands Prix in Australia may have been limited to just two venues across more than thirty years but each has been considered an outstanding success. Adelaide set new standards for a temporary track when introduced to the calendar in 1985, the South Australian venue settling the championship in a spectacular manner for Benetton’s Michael Schumacher in 1994. A heavyweight political battle saw the state of Victoria wrench the country’s Grand Prix away from Adelaide to Melbourne in 1996, switching from the end to the beginning of the year in the process. Jacques Villeneuve (Figure 1) caused a sensation on his F1 debut by taking pole position in his Williams-Renault in 1996, while Michael Schumacher (Figure 2, in 1999) won four times for Ferrari.

Figure 1

Figure 2

■ SINGAPORE

Singapore delivered high standards when it arrived on the F1 scene in 2008 and not only established a challenging track on the streets of the business district alongside Marina Bay but also chose to become the first Grand Prix to be run at night. Powerful overhead lights successfully replicated daylight conditions for the drivers while producing a spectacular sight as the three-mile combination of boulevards and highways passed iconic landmarks such as the City Hall and the cricket ground, as well as crossing the ancient Anderson Bridge. A bumpy surface, angular corners and sapping humidity made this a tough test for the drivers in a race lasting an hour and three-quarters. A contract extended until 2017 was proof of the popularity and success of such a unique addition to the calendar.