3

What Is Queer Philosophy?

University of Pittsburgh

QUEER PHILOSOPHY IS an emergent project. Neither a fully elaborated philosophy of queerness nor a queer philosophy as such yet exists. Queer philosophy should not be confused with a celebration of deviances or perversion, although queer studies of gays and lesbians, the transgendered, the intersexed, the members of fetish communities, and so on have given important momentum to the project. The knowledge held by those outside normative exclusions does prove of particular significance to queer analysis. Queerness, as will be discussed here, is not a question of the marginal or excluded as such, but rather of a universal dynamic. I suggest here that queer philosophy develops out of the realization that queerness constitutes a universal experience of being, although at the moment it may only be recognized as an experience and knowledge proper to a limited number of people. 1 In a sense, queer philosophy emerges as a philosophical attention to queerness.

In the following, I will begin with a historical survey of the emergence of queer theory (to be distinguished from queer philosophy) and a brief discussion of its domain of analysis. Queer theory, like other critical theories, developed in a particular relationship to material conditions and the strivings of liberation movements. After the introduction, I will attend to a “querying” of the work of Kant as an example of a queer theoretical engagement with the Western philosophical tradition. The discussion will then seek to distinguish the potentials of queer theory from queer philosophy where the latter moves into a second order of abstraction, investigating the universality of queerness rather than focusing on particular manifestations. In what follows, I want to be clear that in my distinguishing queer philosophy from queer studies in particular and from queer theory’s general commitment to gay and lesbian specificity, I am not trying to say that gay studies, trans-studies, and so on are not important. They should be done. However, I would contend that at this point an orientation toward universality and abstraction can actually create a situation in which we can better understand the specific and limited. As when critical race studies began to attend to non-U. S. constructions of race, the second-order orientation of the questions posed obviate residual essentialisms. Queer theory/philosophy both derive from the antiessentialist impetus that developed out of social constructionism and performativity.

Queer philosophy follows this trajectory one step further. Because the comparison of queer theory and philosophy I undertake is akin to a neo-Hegelian position—queer philosophy as deriving from the history of queer thought—the discussion here will then give way to a focus on Hegelian philosophy, in particular the question of alterity. Finally, the chapter will turn to a reflection on the possibilities of queer knowing.

The Emergence of Queer Theory out of the Spirit of Gay Liberation

The quest by gays and lesbians for civil rights gained momentum in the 1960s. Sparked by the energy of the Stonewall rebellion in New York (June 27-31, 1969), a new militant movement emerged and spread rapidly beyond the United States. The struggle for gay liberation flourished in the 1970s. As a movement, it became radicalized through the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and infused majoritarian national political debates in the 1990s. And since sexual orientation has expanded into the discourse on human rights, it has also come to have an impact on geopolitics. This movement emancipated a new positive subject from long years of pathologization and criminalization. In spite of the mountain of prejudicial evidence serving as foundation to legal, medical, religious, and educational institutions, the women and men of the early movement took a brave stance to insist on the equality and rationality of their lives and aspirations. The quest for liberation undertaken by gays and lesbians thus required not only a form of direct political engagement and community organization but an extensive revision of heteronormative knowledge. Gay liberation thereby compelled the emergence of gay and lesbian studies as a means not only to counter prejudice but also to promote an appreciation of the cultural production of gays and lesbians. Just as gay and lesbian studies had a clear relationship to the gay and lesbian liberation movements, it mirrored the dynamic that developed also with other directions in the new social movements of the sixties and seventies, for instance the relationship between the women’s movement and the simultaneously developing area of women’s studies.

Gay and lesbian studies thus started primarily as descriptive studies by and for participants in the era’s movement. Lesbians and gays sought first to produce new positive knowledge for themselves and then secondly to develop a critical position from which they could respond to the overwhelmingly negative discourse of homosexuality. Lesbian and gay studies became established within academic settings. Across disciplines, quantitative sociological analysis, psychological studies, literary and historical studies all entered into new terrain to comprehend the lifeworld of the emancipated homosexual. In culturally and historically comparative research gay activist scholars begin to seek their counterparts across time.2 And in this quest for knowledge an interesting break began to emerge.

Certainly it was clear that the era after the Stonewall rebellion differed significantly from other eras. However, the work of historians like Mary Macintosh, Michel Foucault, and Jeffrey Weeks proved especially significant in revealing how the subject emancipated by gay liberation differed in its social construction from other historical subjects.3 Same-sex desire might be a historical constant but its particular expression from epoch to epoch, place to place, differed dramatically. Thus, they suggested, there were no gays among the participants in the early Christian church; there was no direct line of thought from Plato to Oscar Wilde to Andy Warhol. Compelled in part by virtue of such studies, the recognition that the era of gay liberation was not a culmination of a transhistorical logic, that it itself might give way to a new and hitherto unexplored era, opened up the possibility for gay and lesbian studies to enter into a level of abstraction in thinking about sexuality and desire as such. This recognition, and the debates it unleashed, made possible a significant move from descriptive studies to descriptive theory, a point I want to underscore and to which I will return.

The complex consideration of sexuality and desire, however, opened up the possibility of exploring other forms of sexuality beyond a singular focus on a homosexual/heterosexual divide. This new attention also corresponded to the emergence of new sexual liberation movements in the 1980s. Considerations of bisexuality, S-M, and transgendered experiences expanded the perspective of research to a broader set of identities and fostered the development of the term “queer studies” as a collective designation. 4 Queer studies remained, at its core, identity and community based. Within it, identitarian studies like lesbian studies or transgendered studies explore the exclusion of particular groups of people, particular types, particular behaviors, striving variously for inclusion or transformation of the existing system. “Queer” as a term in queer studies, however, served not so much to designate an identity position, rather it pointed to an interest in a further move toward abstraction. “Queer” then served as a placeholder for specific identities, for the sake of propelling them into a first-order abstraction. It did not signify the meaning of these identities.

We can thus distinguish two directions here from each other: queer studies from queer theory. Queer studies emerged in the 1990s in direct relation to political and social movements and communities, while queer theory developed at the same time following more abstract interests.5 To be sure, at this time queer theory still had a close relationship with the sexual liberation movements now expanded and radicalized under the pressure of the AIDS crisis. However, I would suggest that queer theory, drawing from insights offered by various materialist, feminist, structuralist, and poststructuralist discourses, continued into a second order of abstraction. Queer did not serve as an umbrella designation for specific sexed and gendered communities; rather, it emerged as a radical critique of gender and sexual essentialism, heteronormativity, and dominant subjectivity in general.6 Leo Bersani, Judith Butler, Sue-Ellen Case, Joan Copjec, Douglas Crimp, John D’Emilio, Lee Edelman, Anne Fausto-Sterling, Michel Foucault, Elizabeth Grosz, David Halperin, Donna Harraway, Gert Hekma, Teresa de Lauritis, D. A. Miller, Michael Moon, Harry Oosterhuis, Gayle Rubin, Joan Scott, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, James Steakley, and Michael Warner, among others, offered significant contributions to the development of queer theory. To be sure, because their work attended to specific questions of gender and sexuality, their work certainly overlaps with queer studies. Yet their work established queer theory as a significant direction in cultural analysis appropriating a variety of productive critical tools: for instance, social constructionism, the concept of homosociality, antiessentialism, antinormativity, heterogeneity, fluidity, and performativity, among others.

The terms of critical analysis queer theorists developed do engage with material lived experience, but they also open up a metacritical discussion that often seems distant from the streets. Indeed, aspects of the work of queer theory have complicated the presumptions of identity- and community-based politics. Leading figures in the development of queer theory like Judith Butler have repeatedly experienced attacks for a distance from “real-world politics.”7 These types of attacks indicate that queer theory has moved away from the position occupied by lesbian and gay studies. There can be no doubt that queer theory has developed as a descriptive theory addressing a spectrum of lived human experiences that exceeds such pairs as heterosexuality/homosexuality, female/male, and femininity/masculinity. And inasmuch as lived material experience evidences a great deal of complexity, we must also expect a similar complexity from our descriptive apparatus. In this regard, queer theory proves more capable of apprehending the world in its complexity and totality than gay and lesbian studies does. At the same time, queer theory has also moved increasingly into a level of abstraction that derives not from what is given in a particular moment in the material world but rather from questioning what possibilities might be there that transcend the apparent limits of a particular moment.

I would like to focus then on this question: What kind of relationship can we recognize developing between philosophy and queer theory? We might posit it as a move into increasing levels of abstraction, although increasing abstraction does not mean distance from social-material concerns. Abstraction does not mean queer philosophy would strive for complexity as such but rather that queer philosophical abstraction affords a cohesion in perspective; it increases clarity. Furthermore, we could consider the development I am describing of queer studies into queer theory into queer philosophy as some process of supercession. However, each move does not replace the other. The information offered by gay studies allowed the debates around the social construction of sexuality to arise. The information transgendered studies afforded about the expression of gender allowed for the discussion of performativity to arise. Social constructionism and performativity in turn not only compelled the development of queer theory but had a significant effect on research in gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgendered histories.8

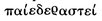

Queer philosophy emerges in its own right first as queer theoretical tools are used for a sustained critique of the discipline of philosophy. Such queer critique can develop in a number of ways. Queer theorists can seek to rewrite the history of philosophy, by discovering lost or silenced texts and philosophers, by countering heterosexist presumptions with evidence of other economies of desire inscribed in philosophical texts. For instance, we could foreground Plato’s relationship to  (pœderasty) or the Marquis de Sade’s relationship to Enlightenment thought. Queer as an umbrella designation of various identities can search through the history of philosophy to find and counter negative images of same-sex desire, of bisexual desire, of transgendered experience, and so on. In following these directions queer theory would not undertake analyses that distinguish themselves significantly from gay, lesbian, transgendered studies. In the 1970s and 1980s, especially gay and lesbian studies sought to accomplish such revisions of the literary and cultural canon. They strove for positive images, forgotten histories, and sought to formulate critical responses to the biases that led to exclusion. Or queer theoretical critique can “query” particular aspects of philosophical discourse to develop the term “queer” in itself.

(pœderasty) or the Marquis de Sade’s relationship to Enlightenment thought. Queer as an umbrella designation of various identities can search through the history of philosophy to find and counter negative images of same-sex desire, of bisexual desire, of transgendered experience, and so on. In following these directions queer theory would not undertake analyses that distinguish themselves significantly from gay, lesbian, transgendered studies. In the 1970s and 1980s, especially gay and lesbian studies sought to accomplish such revisions of the literary and cultural canon. They strove for positive images, forgotten histories, and sought to formulate critical responses to the biases that led to exclusion. Or queer theoretical critique can “query” particular aspects of philosophical discourse to develop the term “queer” in itself.

The Critique of Willed Reason

Let me offer a brief digression as exploration of some possible ways that queer critique of philosophy can open up the work of, for example, Kant. Turing our attention to Kant here begins our specific exploration of queer philosophy as a neo-Hegelian exploration, beginning via a queer history of philosophy. Contemporary philosophers often make a distinction between Kant’s pure philosophical writings, namely the three critiques of reason and judgment, and his more political and anthropological writings.9 They variously dismiss or marginalize Kant’s writing about life on other planets or about the causes of differences in skin pigment. Or they ascribe to a different category his reflections on how to achieve perpetual peace or how to promote enlightenment. For queer theory, this division becomes significant because it has the effect of separating Kant’s work on gender and sexuality as anthropological from his critical consideration. The “pure” philosophical writings thereby undergo a form of extraction from the overall oeuvre, a distinction that Kant himself certainly did not make. In this case, a queer critical approach reveals how a philosophy of human rationality and subjectivity takes shape on the basis of a particular perspective on gender and sexuality. It reveals how modern philosophy is grounded on a certain vision of human intimacy and that later commentators ignored or overlooked the presumptions having developed as “common sense.”

After the discussion of The Critique of Pure Reason (1781) with its concentration on the abstract and transcendent qualities of pure reason, Kant then addressed the role of reason in the objective world through his discussion of The Critique of Practical Reason (1788). He focused on the means whereby the subject described in the earlier critique came to express itself and have effect on the objective world: through the will as determining force exercised on the objective world. The will provided the bridge between pure and practical reason. Kant wrote on this point, arguing:

For here reason can at least attain so far as to determine the will, and, in so far as it is a question of volition only, reason does always have objective reality. This is, then, the first question: Is pure reason sufficient of itself to determine the will, or is it only as empirically conditioned that it can do so? (Prac R, 15)

Such theorizing certainly appears abstract. However, his discussion of the will did not debut in The Critique of Practical Reason. Rather, it was in The Groundwork to a Metaphysics of Morals (1785), written shortly before Practical Reason, that Kant set forth the basis of the terms through which the will operated.

The dependence of the faculty of desire upon feelings is called inclination, and this accordingly always indicates a need. The dependence of a contingently determinable will on principles of reason, however, is called an interest. This, accordingly, is present only in the case of a dependent will, which is not of itself always in conformity with reason; in the case of the divine will we cannot think of any interest. But even the human will can take an interest in something without therefore acting from interest. The first signifies. practical interest in the action, the second, pathological interest in the object of the action. The former indicates only dependence of the will upon principles of reason in themselves; the second, dependence upon principles of reason for the sake of inclination, namely where reason supplies only the practical rule as to how to remedy the need of inclination. (414)

In this discussion, Kant defines will through a series of distinctions that set apart desire, feeling, inclination, and need; moreover, he distinguishes types of will motivated by pathological dependencies and interests. He relegates therewith a whole plethora of forces that motivate human actions outside willed reason to the realm of the irrational and immoral. Kant thus establishes a position of a rational moral subject and an antipodal immoral desiring individual.

The discussion remains perhaps abstracted unless the critical investigation attends to how such a distinction comes to affect Kant’s understanding of social organization. We can intuit that the presumed immorality of this desiring individual stands in for precisely the host of subjects that may be designated as queer. I would suggest that this desiring individual actually identifies the fundamental position of the queer subject in modern Western philosophy. Remaining specifically focused on Kant’s work, however, we can recognize how this desiring individual comes to define and position whole classes of people.

In his later moral work, after articulating the necessity of willed reason’s independence from any determining irrational force, for example, lust or desire, we can find how he asserts an interconnection between marriage and pure reason. He writes:

Even if it is supposed that their end is the pleasure of using each other’s sexual attributes, the marriage contract is not up to their discretion but is a contract that is necessary by the principle of humanity, that is, if a man and a woman want to enjoy each other’s sexual attributes, they must necessarily marry, and this is necessary in accordance with pure reason’s principles of Right. (Metaphysics of Morals, § 24)

Marriage offers a necessary contract whereby two parties can enter into sexual union rationally. They thus must not fear that their lust has debased them by taking control of their will. Kant, restricting marriage to a heterosexual union, thereby relegates all other forms of affective sexual relations to a place outside Right, outside justice, outside morality, outside rationality, and ultimately outside the state.

In his Anthropology (1798), through the dictum that “the woman should reign and the man should rule, because inclination reigns and reason rules,” Kant then established a condition whereby all women became aligned with inclination (Anthro, 309 303.17).10 This alignment positioned women precariously outside reason. It had significant ramifications for their role in the household and ultimately the state. Distinct from rationality, he established a loose set of autonomous feminine characteristics involving passivity and weakness, which would subordinate women in the household.11 In The Metaphysics of Morals (1797), Kant established a dominance of the husband based “only on the natural superiority of the husband to the wife in his capacity to promote the common interest of the household, and the right to direct that is based on this can be derived from the very duty of unity and equality with respect to the end” (Metaphysics of Morals, § 26). The household came to define a whole series of dependencies: wives, and children, as well as all the people who worked for the household, whether it be as cook, cleaner, or wood chopper. Kant, in his own words summed it up in this way, “[A]ll women and, in general, anyone whose preservation in existence (his being fed and protected) depends not on his management of his own business but on arrangements made by another (except the state). All these people lack civil personality and their existence is, as it were, only inherence” (Metaphysics of Murals, § 46). Because the father-husband disposed over the household, those individuals who depended on the household for their livelihood occupied a heteronomous condition, unable to exercise their reason freely. Contractual heterosexual relations impel the Kantian subject. Furthermore, they establish relations of dependency and sovereignty, thus differentially allocating capacities for reason. This difference begins with gender and desire. Such relations do not only establish a governing imperative over same-sex desire but over all forms of sexuality and all forms of relationships, inasmuch as all relationships are gendered. It just as much governs the relationships of the head of household to his male servant as it does that of the relationship of the husband and wife, or the husband and concubine.

This excursion through the works of Kant could continue much further, but the point was first to draw out the connections between the “abstract philosophical” and the practical writings. We can certainly see that Kant sought out practical relations and applications among the various levels of his works. Then returning to the question of queer theory’s engagement with philosophy, we can further see how queer critique opens up new approaches and relations to Kant’s work. Some feminist scholars, attending only to the discussions of women’s roles in Kant, have sought to enter into a reformist relationship that identifies the anthropological and moral texts as sexist while leaving the critiques as descriptive of a universal subjectivity.12 Such an approach seeks to hold open the possibility of women simply finding inclusion in Kant’s Enlightenment subject. By including assessments of sexual desire, we recognize how willed reason acts as an abjecting mechanism, foreclosing for vast portions of humanity the possibility of participation in the Kantian universal moral subject. In doing so we recognize the important correspondences between gender and sexuality and feminism and queer theory. The definition of the desiring individual does not only have an effect on women but also on members of other categories based on age, sexuality, property position, income dependence, and so on. Moreover, we can begin to recognize how his philosophy, understood as the height of the Enlightenment, establishes preconditions for gendered and sexual domination in the modern era. It proves insufficient to describe Kant simply as influenced by heterosexism. We can see that Kant actually promotes heteronormative structures. His understanding of rationality is compelled by a heterocoital imperative that relegates other economies of desire, and desire as such, outside reason and morality. From a queer critical perspective then, we would insist that “desiring individuals” too have rationales and ethics which Kantian reason cannot contain.

Thus a queer critique, in order to accord rationality to the queer subject, compels a break with this dominant sex-gender paradigm and fundamentally rejects the distinctions by which Kant defined willed reason. In order to contain the reason of the “desiring individual,” queer critique thus would inspire in a philosophical system a reformulation of reason, will, morality, universality, and so on. If we rely on this recognition to define the direction of queer philosophy, then, I suggest, queer ethics or queer discussions of reason would begin from the point that all rationalities and ethics are situational, negotiable, and not exclusive of some practice or some group. Thus, we follow a move into increasing philosophical abstraction away from the concerns of a gay or feminist movement. Queer theory, as it moves beyond the “umbrella function,” enters into a level of significant abstraction (not unlike certain influential strands of feminist theory). It is not only a matter of positive descriptive identity and community studies. Queer critical engagements can, in the overused but important formulation, “query” philosophical texts to arrive at new knowledge. This new knowledge in turn opens up new possibilities of practical activity.13 Queer philosophy does not reject philosophy as much as works its way through it.

Queer Theory Is Not Yet Queer Philosophy

While queer theory marks certain significant developments, still queer theory is not equivalent to queer philosophy or queer science. This distinction might seem odd given, on the one hand, a tendency in literary and cultural studies to collapse theory and philosophy as terms. On the other hand, the quest for queer science might also seem odd given the general abdication of scholars in the humanities from understanding their work as contributing to the human sciences. By distinguishing queer theory from queer philosophy, I am certainly not interested in enforcing disciplinary boundaries but rather in thinking about long-range and full possibilities for the term “queer.”

In that queer theory developed its tools of analysis out of the legacy of Western philosophy, it is like other contemporary forms of critical theory. The work of Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche, Freud, Heidegger, Saussure, Pierce, Wittgenstein, Derrida, and Deleuze, among others, offered a foundation upon which queer theorists built. However, in contradistinction to gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgendered studies that relied primarily on positivist, sometimes quantitative, and formalist analyses of historical events, communities, and texts, queer theory as critical theory has a distinct ability to engage philosophical discourse as such—like feminist theory and critical race theory. Yet queer theory has not yet developed a sustained critical engagement with its own foundation. In this regard, queer philosophy is an emergent discourse only now coming into its own. For queer theory to develop into queer philosophy, it requires a critique of its own foundation in modern Western philosophy. Only through such a critique can it accomplish the epistemological break that would distinguish it as a self-consistent philosophical discourse. Queer philosophy has a great contribution to make to the study of philosophy as a critical position vis-à-vis the first history philosophy.

In a trajectory in the history of ideas marked by, for instance, Kant, Hegel, and Marx, we would typically recognize significant ruptures and radical critiques. In the common story of developments, Hegel’s idealism rejected the Kantian subject, while Marx’s materialism put Hegelian philosophy on its head. Hegel broke with Kant, Marx broke in turn with Hegel. Yet precisely in this trajectory we could recognize that as radical as the presumed ruptures are, these three divergent, even antithetical philosophical directions nevertheless share a common root in that each shares a presumption of heterosexuality as the sine qua non of rational social subjects. We saw how in the development of his system, Kant allocated the properties of reason to the male head of the household, leaving de facto all nonsovereign dependents—wives, daughters, servants, and the nonhetero-sexual—permanently outside reason. Hegel similarly intensified the significance of the hetero-coital imperative, making it the basis of civil society, the resolution of the dialectic, the key to the ethical order. Marx and Engels relied on a natural sexual division of labor, a distinction of reproduction and production, and, inasmuch as they critiqued double standards in bourgeois sexual morality, they still held out heterosexual “sex-love” as the sign of the revolutionary accomplishment of positive proletarian culture. What does this mean for philosophy in general and the development of queer philosophy specifically?

Hegel suggested that philosophy is the history of philosophy. The project he undertook understood itself as the beneficiary of all the knowledge developed before it, all the ideas found in the long recorded history of ideas. Hegel, as is well-known, understood his position as the culmination of a long development that allowed him to recognize objectively the telos of history. While we might easily take exception with Hegel’s understanding that the spirit of freedom had found its historical home somewhere outside his window in early nineteenth-century Prussia, nevertheless I would still suggest that the project of an all-inclusive history of philosophy affords us not only a sense of significant knowledge but a hope for real wisdom and even possible insight into how to inhabit the world fully. However, the general project of Western philosophy to which Hegel contributed developed in a manner that made it impossible for philosophy to accomplish its own love of wisdom. It could not fully disclose the world it inhabited to itself because it could not acknowledge the full complexity of the history of philosophy. If, as Hegel suggested, philosophy is the history of philosophy, then the dominant narrative of modern Western philosophy has developed not in simple ignorance of the full range of lived human experiences but through active negation of the complexity of social, sexual, and affective relations. A queer critical engagement with the history of philosophy begins from this point, seeking to reveal that the project of modern Western philosophy is a history determined by a heterocoital imperative.

We need not look too far to find alternatives to this history; we can easily remain within the Western Eurocentric narrative. Certainly classic Greek and Roman philosophy recognized sexual economies that went beyond reproductive sexual relations. In this regard, a history of philosophy can reveal that affective and physical relations had forms quite different from the bourgeois nuclear family of the modern period. Such knowledge was certainly available to the modern period. Yet the modern European philosopher proved discontent to allow the particular economies of gender and sexuality that had developed to stand as one of many possibilities in the world. Nor did a history of sexuality prove sufficient to offer philosophy an awareness of an inherent permutablity of lifeworld relations. Rather, the modern period, infused with a belief in progress and in its own position as vanguard in perfecting the history of the world, emerged not simply as a repudiation of other sexual economies but as a foreclosure of any possible positive effect of their knowledge. This is not to suggest that scholarship does not exist in the modern period that seeks to account for, describe, and represent the real heterogeneity of human physical and emotive relationships. To be sure, traces of actual alternatives to hetero-coital sexuality fill modern philosophy, literature, and the arts. Yet such alternatives were excluded from the dominant mode of philosophy. Indeed, the history of philosophy that dominated in the West relied on the reproductive monogamous couple to accomplish its domination.

Recall that from at least the seventheenth century onward, for a host of liberal philosophers like Kant grappling with morality, their discussion of rights did not lead to a general consideration of ownership and private property but to an estimation of a particular form of the household present in the merchant and middle class. In the course of three centuries of philosophical development, the bourgeois nuclear household, as a site of hetero-coital activity, came to define parameters of rationality, naturalness, morality, ethics, citizenship, civil society, sociability, revolutionary subjectivity, and so on. The desiring individual, aberrant from this particular form of heterosexual activity, came to define the irrational, abnormal, inhuman, immoral, unethical, unreasonable, corrupt, selfish, excessive, uncontrolled, wandering, antisocial, seditious, and so on. Deviations from this “ideal” occupied a queer position, and representations that even sought to address the queer as a site of positive potential could easily be positioned into threats against the good as such. From this point a queer critique of modern philosophy begins.

The hetero-coital imperative did not limit only the development of modern German philosophy. In this respect, Kant, Hegel, and Marx do not represent a separate path, a Sonderweg, in the modern period; rather, they participate in the objective tendencies of domination within modern philosophy as such. The emergence of queer theory at the end of the twentieth century marked for the first time a possibility within the history of Western philosophy for a break with the hetero-coital imperative. I offer that the break with the hetero-coital imperative, however, is only the starting point of the critical potential of queer theory.

To clarify what must happen to accomplish this transition, I want to reflect for a moment on certain basic terms being used here: theory, knowledge, philosophy, science. Theory certainly informs knowledge. There is no positivist fact bearing truth in itself. There is no theory-free observation, and a Weberian value-free theorizing only accomplishes a foregrounding of how theory makes knowledge possible. Although this position is one shared with many directions in philosophy, it serves as foundational to a queer critique. Theory’s root in classical Greek,  (theoria), meant to look at, view, contemplate. As such it was bound to observation and spectacle. For the Greeks, a theorem was a proposition to be proved to a spectator. Theory in this understanding is not abstract from material conditions; rather, it is part of sense-making in the world. A theory offers a system to account for a set of phenomena, a method for comprehending a cultural artifact, a schema for describing a mode of production.

(theoria), meant to look at, view, contemplate. As such it was bound to observation and spectacle. For the Greeks, a theorem was a proposition to be proved to a spectator. Theory in this understanding is not abstract from material conditions; rather, it is part of sense-making in the world. A theory offers a system to account for a set of phenomena, a method for comprehending a cultural artifact, a schema for describing a mode of production.

What does it mean to bring queer and theory together as a designation? The etymology of queer is unclear. Although the etymologists quickly point out that the timeline remains unclear, the OED traces its roots back to the German quer. cross, oblique, squint. Queer in its earliest usage describes an experience or a form of apprehension in which something is recognized as strange, other, different, out of the ordinary. Queer does quickly take on a vulgar usage as in “dirty rotten queer” to describe people of nonnormativized gender and sexuality. Its initial contemporary use in queer theory marked a form of reclamation vis-à-vis this vulgar connotation: queer theory as focused study of those people’s experiences outside the gender and sexual norm. This reclamation project and a new queer pride, however, continues to meet with opposition from many members of the lesbian and gay liberation movement, who do not find it possible to imbue such a negatively loaded word with a sufficient form of positivity in order to be a vehicle of pride.

What intrigues me to note, though, is that queer as oblique, squint, strange, other, does describe an aspect of theory and theorem that needs to be underscored. Theory differs from awareness of recognition in that it approaches an appearance in the world that does not (yet) make sense. Only that which is out of the ordinary, strange, oblique to understanding requires the regard and contemplation of theory. Only that which is not comprehended must be held up as theorem, to be “squinted” at. Theory. proves necessary as the bridge between apprehension and comprehension. Queer proves descriptive of the fundamental motivation for theory, to make sense of that which stands outside the understanding.14 It does not mean that what is queer is unreasonable or irrational but that it is a disruption to accepted rationales and in order to find its reason theory must arise to describe it. In this regard queer theory thus describes a dynamic inherent in and constitutive of the descriptive aspirations of all theorizing. All theorizing is queer theory. Queerness is the “unconscious” of theory.

At this point, however, we want to note that in the history of philosophy a form of theoretical apparatus has arisen, as we discussed above with Kant, that rather than comprehend the compelling quality of queer actually seeks to contain and restrict the impact of its potential by barring it from reason or rationality. Of course, the investigation of how we apprehend in space and time was fundamental to Kant’s theoretical apparatus, yet we can also begin to recognize that the overall project, in the approach it took to desire and reason, also sought to establish limits on what we can comprehend. Kant’s theorizing, as part of the trajectory of modern Western philosophy, proved unable to develop as queer philosophy.

Queer Philosophy Is Not Queer Science

Stepping back for a moment from queer theory, let us note that descriptive theories are the beginning of philosophy but we might want to distinguish them from philosophy as such. A descriptive theory begins then from observation of (queer) material relations but has arrived at only an initial level of abstraction. Descriptive theory cannot move into philosophy without passing through three transformations. It must first arrive at a level of abstraction that allows it to recognize how history and location determine and specify the observed conditions. Then, second, it must identify what objective tendencies in history transform historically or spatially specific conditions. Finally, it must comprehend what structures transcend one condition into another. This knowledge, deriving from abstracted principles, arrives at the level of science, scientia.

Philosophy, philo Sophia, Aristotle distinguished from  (phronesis), which is the form of philosophical wisdom that motivates just behavior and proper living. It derives from experience of the world. For the post-Aristotelian Stoics and Epicureans, however, the distinction gave way to a focus on philosophy not as a pursuit of divine knowledge but of practical wisdom. From this point onward, there is a circle that arises with theory, science, and philosophy that is fundamentally practical in orientation. I argue here that philosophy distinguishes itself from belief or opinion in that it moves from theoretical knowledge derived by direct acquaintance, through the abstraction of scientific knowledge, back into engagement with the material world. Really, though, wisdom follows theory in that it does not appear in the quotidian; it is only in confrontation with the strange that wisdom must arise and intervene. Only when we have a sense that something does not follow our expectations, is unusual, do we call upon wisdom. Queer philosophy then is that philosophical stance that does not foreclose the possibility of understanding the strange. It acknowledges the extraordinary and accepts the transformative aspect such acknowledgment initiates. Queer philosophy does not reject the strange desire as irrational but rather proves open to extrapolating across rationales in order to expand wisdom. Not all philosophical systems have proven equally able to comprehend the knowledge of the strange. Modern philosophy emerged by delimiting, excluding, setting boundaries between things, notions, people. Queer knowing arises in the transition across such limits. It is the task of queer philosophy to focus on the dynamic of queerness. It can begin this task by reassessing the knowledge of those people excluded as desiring individuals. Inasmuch as queer theory can develop into queer philosophy, a queer way of knowing, there lies a possibility of a radical break in philosophy whereby the history of philosophy is able in its universality to come into its own, finally. It is not within or against, but through and beyond the existing system of Western philosophy that queer philosophy directs its project.

(phronesis), which is the form of philosophical wisdom that motivates just behavior and proper living. It derives from experience of the world. For the post-Aristotelian Stoics and Epicureans, however, the distinction gave way to a focus on philosophy not as a pursuit of divine knowledge but of practical wisdom. From this point onward, there is a circle that arises with theory, science, and philosophy that is fundamentally practical in orientation. I argue here that philosophy distinguishes itself from belief or opinion in that it moves from theoretical knowledge derived by direct acquaintance, through the abstraction of scientific knowledge, back into engagement with the material world. Really, though, wisdom follows theory in that it does not appear in the quotidian; it is only in confrontation with the strange that wisdom must arise and intervene. Only when we have a sense that something does not follow our expectations, is unusual, do we call upon wisdom. Queer philosophy then is that philosophical stance that does not foreclose the possibility of understanding the strange. It acknowledges the extraordinary and accepts the transformative aspect such acknowledgment initiates. Queer philosophy does not reject the strange desire as irrational but rather proves open to extrapolating across rationales in order to expand wisdom. Not all philosophical systems have proven equally able to comprehend the knowledge of the strange. Modern philosophy emerged by delimiting, excluding, setting boundaries between things, notions, people. Queer knowing arises in the transition across such limits. It is the task of queer philosophy to focus on the dynamic of queerness. It can begin this task by reassessing the knowledge of those people excluded as desiring individuals. Inasmuch as queer theory can develop into queer philosophy, a queer way of knowing, there lies a possibility of a radical break in philosophy whereby the history of philosophy is able in its universality to come into its own, finally. It is not within or against, but through and beyond the existing system of Western philosophy that queer philosophy directs its project.

Difference and Queerness

Queer philosophy begins from a recognition of difference as centrally constitutive to knowledge. In its emergence out of gay and lesbian studies, queer philosophy had of course to contend with the systematic exclusion of diverse forms of knowing from dominant philosophical paradigms. Queer philosophy overlaps, thus, to a certain extent with considerations of alterity. Yet, to come into its own queer philosophy cannot simply observe relations of difference; rather, it must also apprehend an effect of queerness as such that goes beyond difference. To explain what I mean, I want to focus our attention on alterity, which as a subdomain of philosophy has productively explored for instance how consciousness is constructed in relation to an other.

In this direction of study we understand that the “I” is not alone or, to adopt Rimbaud’s more poetic language, “I” is an other. Emmanuel Levinas offered more recent sustained discussions of alterity.15 But to understand the proposition of consciousness emerging through a relationship of alterity we can turn to Hegel as a foundational statement on the question. We cannot really overestimate the influence of this account of self-consciousness on philosophy, and beyond to psychology, political philosophy, literary studies, cultural studies, and numerous other discourses. It thus merits some attention as it poses, I would suggest, a central notion that queer philosophy must itself supersede.

In The Phenomenology of Spirit (1807), Hegel followed a dialectic procedure that allows for an understanding of subjectivity as (antagonistic) pairs forming a unity. Hegel distinguished consciousness from self-consciousness. Consciousness in itself has no phenomenal objects. Consciousness has only certainty, full knowing of the notion. The notion (Begriff) of the object vanishes in the conscious experience of it. In certainty consciousness as such is homogeneous, all-encompassing. The truth of the other does not exist—yet. I say yet because self-consciousness does require an other. To be self-aware, Hegel explains, requires a sense of limit established by conflict with an other consciousness. The recognition of an equally independent and self-contained consciousness allows the self to be aware of its actions for itself.

We could say that the Hegelian ego is bipartite, like the Kantian, but with Hegel self-consciousness or subjectivity is a relationship with the other and not with a metaphysical condition of reason. When Hegel speaks of self-consciousness as a dialectic, the “I” is bound up with a “Not-I” as the precondition for self-consciousness. The “Not-I” exists as object, as other for the “I” inasmuch as it gives the “I” form. It does not have independence as such, it does not exist for itself; rather, it exists at first as simple determination on self-consciousness. The other develops out of a condition of abstract object for the self only in the unfolding of “Life” (§ 173). We might suggest at this point that alterity tames the effect of the other, presenting it for inspection as constitutive essence. Indeed, in most discussions subsequent to Hegel the character of the other does not draw much attention. For instance, Lacan’s other is bound up with the law of the father but does not need to be identified with any particular man or type of father. Generally, the other exists insomuch as it exists for the subject of self-consciousness.

Certainly, we do know from Hegel that self-consciousness enters into a dialectical relationship with the other. The self, having lost the experience of totality that accrued to simple consciousness, enters into conflict with the other. This condition of conflict establishes an “unhappy, inwardly disrupted consciousness” that takes the other as an enemy who must be vanquished (§ 207). To vanquish the other, however, means a loss of self and a reversion to consciousness. The unhappy consciousness thus discovers that it must learn to find the lost universality of consciousness by some other means.

Much attention has been paid to how Hegel offers one solution to this crisis of self-consciousness in labor. Even Judith Butler discussed the unhappy consciousness both in her first book Subjects of Desire (1987) and in the more recent The Psychic Life of Power (1997), focusing in both studies on the resolution offered by exteriorization in labor. For Hegel, the individual subject turns his desire for universality into a control over a thing, an object of his own production. This marks the emergence of a bourgeois citizen-producer who experiences universality in a marketplace. However, this displacement onto labor and production ultimately remains unhappy because it cannot offer full universality.

I would like to interject two observations about this concentration on unhappy consciousness and labor. First, we can not overestimate how the subject harbors a propensity for violence vis-à-vis the other. This violence is not abstract. For anyone who has ever been attacked because they occupied the position of other to someone’s unhappy self-consciousness, the general disregard for the experience of the other indicates that there is a significant lack of knowledge in this approach. The other is not necessarily a docile object in relation to the aggression of the self. However, the power differentials that exist in self-other relations can make the other a constant object of assault and violence. I will return to this point below. Second, and interestingly, what remains overlooked in Hegel’s account of self-consciousness is that he does offer a resolution to the conflict and it is one that derives from heterosexuality.

Hegel offers love as the resolution to the conflict with the other. In The Philosophy of Right (1821) Hegel wrote: “Love means in general the consciousness of my unity with another, so that I am not isolated on my own [für mich], but gain my self-consciousness only through the renunciation of my independent existence [meines Fürsichseins] and through knowing myself as the unity of myself with another and of the other with me” (§ 158). Elsewhere in The Phenomenology he phrased it thus: “It is the pure heart which for us or in itself has found itself and is inwardly satiated, for although for itself in its feeling the essential Being is separated from it, yet this feeling is, in itself, a feeling of self” (§ 218). In other words, even though the subject struggles to establish self-consciousness, love allows it to experience the universality and unity of being that belonged to the undifferentiated state of simple consciousness. This love, however, is of course not any love and not just the love of man and woman but of husband and wife as progenitors of the family.

Like Kant, Hegel denied a solely procreative function to marriage. The purpose of marriage is primarily to check the natural drives of husband and wife, not to have children. Marriage creates a unity, according to Hegel, that transcends individual drives and needs for the sake of an all-encompassing totality. However, Hegel expressed only disdain for Kant’s definition of marriage as a contract for the mutual use of each other’s sex organs.16 Where Kant began with marriage—not the family—as one form of contractual law, Hegel began with the entire family as love bond sub-lated into ethical mores (Sittlichkeit). Marriage, “the union of the natural sexes,” went beyond this “union” to bring together private property and the socialization of children into the basis of the ethical realm.

At the heart of Hegel’s ethics of the family is a highly elaborated es-sentialization of gender distinctions, marking two types or characters that primarily inhabit distinct public and private spheres. Complementary characteristics make logical Hegel’s apportionment of the social sphere into two interrelated spheres: the house as the feminine sphere of activity and the world outside the house as the masculine. “Man therefore has his actual substantial life in the state, in learning [Wissenschaft], etc., and otherwise in work and struggle with the external world and himself.... Woman, however, has her substantial vocation [Bestimmung] in the family, and her ethical disposition consists in this [family] piety” (§ 166). In such oppositions we recognize an intensification and rupture of Kant’s characterization of women and men within the household.

Gender distinctions defined oppositions that were not dialectical but natural and essential. Even though they represent positive and negative determinations on individual existence, Hegel did not understand them as contradictions that would drive the dialectic. In the heteronormative husband/wife relationship, Hegel charted out a system whereby the posited natural, essential characteristics of masculinity and femininity complemented each other to give rise to a harmonious social order. Thus we have in this harmony a vision of a perfected dialectic. The heterosexuality of the family suffused the entire social order with ethical form. Defined as essential, the gendered difference gave rise to heterosexuality as one of the first signposts of the ends of history.17

It is thus crucial to recognize that laeterusexuality is not simply a preferred form of sexuality, one among many. Instead, it provided the prototype for the kind of social homogeneity that was at the heart of Hegel’s positive social totality. Heterosexuality here is not simply a compulsory form of sexuality. Rather, it ascends to the ethical norm that pervades the entire nation-state. It is the knot that binds the totality together. Without heteronormativity, the Hegelian social structure, a social structure that infuses the philosophy of modernity, falls apart into contingencies, particularities, and accidentalities of desire. This state of diffusion worries the Hegelian system.

Out of this lengthy discussion, I want to highlight three aspects. First, paradigms of alterity tame difference not simply by contending primarily with the subject, but also, as is clear in the Hegelian system, by containing difference to stabilized essences. Gender as natural essential difference provides an inescapable form of determination. Heterosexuality as natural essential final sublation of difference positions all other forms of desire as unnatural inessential. A queer critique of the Hegelian system that begins by questioning gender as essence or by rejecting the naturalness of heterosexuality cannot end with a simple attempt at inclusion as different differences. Nonnatural, nonessential difference does not resolve the propensity for violence inherent in self-consciousness.

Second, the critique of the hetero-coital imperative as structuring the logic of the Hegelian system alludes to a queer propensity that exceeds difference. Recall that Derrida similarly underscored in the neologism différance the instability of differing and deferring in every system. Queerness, however, is not just the instability of every system, but rather the destabilizing compelled by the systematic exclusion of knowledge. While a system such as the Hegelian can contain difference, queerness compels systematic transformation. Deconstruction recognized the instability of all systems. Queerness works by rupture, revealing partiality of reason and exclusion as a price of systematicity. However, deconstruction affords primarily negative critical knowledge. It is nihilistic in the Nietzschean sense. Queerness propels movement beyond systems but not necessarily because it is itself systematic, nor can one assume that the transformation propelled by it is in any sense systematic. Queer philosophy opens up possibilities of positive knowledge. It is, in the Nietzschean sense, joyful.

Third, queer philosophy, inasmuch as it recognizes both the insufficiency of difference and the destabilizing effect of the queer, can develop by offering new approaches to the presumed violence of self-consciousness. To that end I would like to offer a few brief comments that give direction to a consideration of queer subjectivity and sociablity. If we return to Hegel we can recognize that even in identifying heterosexual difference as resolution of the dialectic, Hegelian self-consciousness does not become a mystical unity of self and other. The family represents for Hegel a limited field of harmony that restores to the self-conscious subject some sense of the universality experienced by simple consciousness. The family, however, precisely in its most “natural” form, is a filiative determination on the child. Without a subsequent rational affiliation akin to the commitment that initially convened the family unit, the child can only experience the modern nuclear family as a totalizing force on its will, not as a field of universality. Without rational affiliation, the Hegelian nuclear family based in “love” threatens to be the antithesis of Hegel’s description.

The self-conscious subject appears, however, able to carry out an act of rational affiliation. Recall that even for Hegel, the “Not-I” gives the “I” an understanding of the whole of differentiated being; consciousness arrives at self-consciousness through an awareness of its own thinking as differentiated and finite. The self-awareness of finitude affords also an awareness of the plenitude of the other. We do not even need to know consciously the other to be aware that the other holds open new possibilities of knowing for the self. Really, Hegelian self-awareness is a very curious development when examined closely. We do not even need to know the other for the other to effect a change in consciousness. The inter-subjective experience of the other drives an inner-subjective state in the self. Hegel writes, “Now, it is true that for this self-consciousness the essence is neither an other than itself, nor the pure abstraction of the ‘I,’ but an ‘I’ which has the otherness within itself, though in the form of thought, so that in its otherness it has directly returned into itself” (Phenomenology, § 200). We cannot consciously know an other given the autonomous independence that a priori defines the other, but we can be self-consciously aware of knowledge offered to us by the other.

Queer philosophy need not begin from the presumption that self-consciousness begins as violent. Rather, given the inner-subjective state, we can understand that the subject arrives at self-awareness predisposed to intersubjective sociability. We rationally can aspire to avail ourselves of the knowledge of the other. In this regard when in The Phenomenology Hegel suggests that “self-consciousness is Desire” (§ 174), it is not violent desire. Hegel, compelled by a hetero-coital imperative, can only imagine positive desire between the sexes. For the public realm of civil society and state he can only image a masculine homosocial order of violence barely contained by ethics inculcated through filiative “love.” The desire of self-consciousness, freed from distinction as heterosexual desire and filiative love, holds open new vistas for queer philosophical investigation. Self-consciousness as desire for the other seeks its full plenitude in the experiences afforded by others. We can recognize self-differentiation as unleashing a desire that draws us to the other. We do not exist as isolated monads; rather, we willingly, freely, desire sociability—that is, to inhabit lifeworlds with others.18 Ultimately, queer philosophy has the potential to envision a sociable plenitude that radically exceeds the selfish liberation in labor or the limited liberation in the family/nation that Hegel proposes as resolution to the unhappy consciousness.

Gay Science, Queer Knowing

To apprehend the effect of queerness is not simply to observe relations of difference. Nor is it a matter, as in explorations of alterity, to describe the constitutive effect of the other, that is, without object there is no subject, without an other, consciousness cannot become aware of a self, and so forth. Queer philosophy has certain affinities with deconstruction, but queer differs from dilférance. In spite of its critique of logocentrism, deconstruction can find no knowledge outside Western metaphysics. Rather than suggest, as deconstruction does, that to identify something as marginal or outside Western philosophy means that it is actually constitutive of or defining to Western philosophy, queer philosophy begins from the position that the comprehension of excluded or marginal rationales fundamentally transforms the possibilities of (Western) philosophy. Queer philosophy is transformative, not deconstructive.

I have sought here to attend to some of the terms of the critique by which queer philosophy is currently emerging: hetero-coital imperative, heteronormativity, homogenizing, totalizing, universalizing. This list develops inasmuch as queer theory proceeds with the queer critique of its own foundations: As queer theory moves toward a metacritical position, it opens up new discursive possibilities. Queer theory begins to approximate what we might describe as queer philosophy or queer ways of knowing. In this regard it follows the positive route of philosophical engagement charted out by Nietzsche in The Gay Science. Nietzsche strove in this text to accomplish a “joyful wisdom,” a “gay science” that could overcome nihilistic pessimism. His recognition of antiessentialism as a means of revaluation prefigures the project of queer theory and suggests a method by which descriptive theory is able to bridge abstraction and material engagement.

Only as creators!—This has given me the greatest trouble and still does: to realize that what things are called is incomparably more important than what they are. The reputation, name, and appearance, the usual measure and weight of a thing, what it counts for—originally almost always wrong and arbitrary, thrown over things like a dress and altogether foreign to their nature and even to their skin—all this grows from generation unto generation, merely because people believe in it, until it gradually grows to be part of the thing and turns into its very body. What at first was appearance becomes in the end, almost invariably, the essence and is effective as such. How foolish it would be to suppose that one only needs to point out this origin and this misty shroud of delusion in order to destroy the world that counts for real, so-called reality. We can destroy only as creators. But let us not forget this either: It is enough to create new names and estimations and probabilities in order to create in the long run new “thing.s”19

What Nietzsche describes is a form of material engagement, but not the kind that derives from a Marxian materialism. Nietzsche as anti-idealist arrives at materialism by a different route, the full practical implications of which still remain unexplored. Emergent queer philosophy, I would suggest, takes up this direction. It may therefore not prove immediately appropriable for quotidian politics in a manner that some movement activists would like, but that does not mean that it is not practical. Certainly it is not practical. Certainly it is oriented toward engagement with the material world. Queer theory interprets the world, queer philosophy teaches one how to inhabit it fully.

Notes

This essay thus extends the work begun in Randall Halle, Queer Social Philosophy: Critical Readings from Kant to Adorno (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2004).

See for example Zoachary Quill, Homosexuality through the Ages (Los Angeles: Wiz Books, 1969); Kay Tobin and Randy Wicker, The Gay Crusaders (New York: Arno Press, 1975); Vern L. Bullough, Homosexuality, a History (New York: New American Library, 1979); John Boswell, Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality: Gay People in Western Europe from the Beginning of the Christian Era to the Fourteenth Century (Chicago: University of Chicago Press: 1980); Jonathan Katz, Gay/Lesbian Almanac: A New Documentary in Which Is Contained, in Chronological Order, Evidence of the True and Fantastical History of Those Persons Now Called Lesbians and Gay Men (New York: Harper & Row, 1983); Jim Kepner, Becoming a People: A 4,000-Yeur Gay and Lesbian Chronology (Hollywood, CA: National Gay Archives, 1983).

Mary Macintosch, “The Homosexual Role,” in The Making of the Modern Homosexual, ed. Kenneth Plummer (London: Hutchinson, 1981); Michel Foucault, The History cf Sexuality, 3 vols. (New York: Pantheon, 1978-1986); Jeffrey Weeks, Sex, Politics, and Society: The Regulation of Sexuality since 1800 (New York: Longman, 1981).

See, for instance, Brett Beemyn and Mickey Eliason, eds. Queer Studies: A Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Anthology (New York: New York University Press, 1996).

One of the first published uses of the term “queer theory” can be traced to “Queer Theory: Lesbian and Gay Sexualities,” Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 3 (1991), a special issue edited by Teresa de Lauritis.

This discussion of “queer” derives from the lengthier analysis undertaken in my book Queer Social Philosophy: Critical Readings from Kant to Adorno (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2004).

For examples of the dilemmas of the period, see discussions in Judith Butler, interview with Peter Osborne and Lynne Segal, “Gender as Performance,” Radical Philosophy 67 (1994): 32-39; Judith Halberstam, Female Masculinity (Durham: Duke University Press, 1998); Lynda Hart, Between the Body and the Flesh: Performing Sadomasochism (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998); Sally O“Driscoll, ”Outlaw Readings: Beyond Queer Theory,“ Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 22 (1997): 30-55.

There are numerous examples. See for example the classic discussion in Edward Stein, ed., Forms of Desire: Sexual Orientation and the Social Constructionist Controversy (New York: Routledge, 1992).

For a sustained critical discussion of this position see G. Felicitas Munzel, Kant’s Conception of Moral Character: The “Critical” Link of Morality, Anthropology, and Reflective Judgement (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999).

“die Frau soll herrschen und der Mann regieren; denn die Neigung herrscht, und der Verstand regiert.”

See the chapter in his Anthropology on “The Character of Gender.”

See for instance Susan Mendus, “Kant: An Honest but Narrow-Minded Bourgeois?” in Women in Western Political Philosophy: Kant to Nietzsche, ed. Ellen Kennedy and Susan Mendus (New York: St. Martin”s Press, 1987).

Queer theory, like similar strands in feminist theory, critical race studies, or Marxian class analysis, often must suffer an indictment that it is distant from real-world experiences and politics. Such indictments generally do not dismiss the insights offered by these critical directions; rather, they demand a clarity and simplicity of language. While I am sympathetic to a request for jargon-free writing, I would object to the general impetus behind such indictments. We live in a complex and changing world and it proves oddly reductive to expect our theoretical engagments with this world to be less complex and dynamic.

Jacques Lacan; Slavoj Zizek.

See for instance Emmanuel Levinas, Alterity and Transcendence (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999).

See § 75 of The Philosophy of Right.

There have been extensive discussions of essentialism and particularly the significance of Hegel for the proposition of essentialism. For a brief and insightful discussion of Hegel and gender see Seyla Benhabib, “On Hegel, Women and Irony,” in Feminist Interpretations and Political Theory, Ed. Carole Pateman and Mary Lyndon Shanley (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1991).

Kant’s subject got it wrong, it is not rationality and the willingness to limit coercion that establishes sociability. For insightful reflections on the relationship of desire to intersubjective communication and communicability see Slavoj Zizek’s reflections on Schelling in “The Abyss of Freedom,” in The Abyss of Freedom/Ages of the World: An Essay by Slavoj Zizek with the Text of Schelliny’s “Die Weltalter” (Second Draft, 1813) in English Translation by Judith Norman (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997).

Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science (New York: Vintage, 1974).

Bibliography

Abelove, Henry, Michele Aina Barale, and David Halperin, eds. The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader. New York: Routledge: 1993.

Altman, Dennis. “Global Queering.” Australian Humanities Review 2 (1996). http://www.lib.latrobe.edu.au/AHR/archive/Issue-July-1996/altman.html.

———. Global Sex. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Bataille, Georges. Visions of Excess: Selected Writings 1927-1939. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1985.

Baxandall, Rosalyn. “Marxism and Sexuality: The Body as Battleground.” In Marxism in the Postmodern Age: Confronting the New World Order, ed. Antonio Callari, Stephen Cullenberg, and Carole Biewener. New York: Guilford Press, 1995.

Beemyn, Brett, and Mickey Elianon, eds. Queer Studies: A Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Anthology. New York: New York University Press, 1996.

Berger, Maruice, Brian Wallis, and Simon Watson eds. Constructing Masculinity. New York: Routledge, 1995.

Berlant, Lauren. The Queen of America Goes to Washington City: Essays on Sex and Citizenship. Durham: Duke University Press, 1997.

Bersani, Leo. Homos. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995.

Blasius, Mark, and Shane Phelan, eds. We Are Everywhere: A Historical Sourcebook of Gay and Lesbian Politics. New York: Routledge, 1997.

Boswell, John. Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980.

Breines, Paul. “Revisiting Marcuse with Foucault: An Essay on Liberation Meets the History of Sexuality.” In Marcuse: From the New Left to the Next Left, ed. John Bokina and Timothy J. Lukes. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1994.

Brown, Wendy. States of Injury: Power and Freedom in Late Modernity. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995.

Butler, Judith. Antigone’s Claim: Kinship between Life and Death. New York: Columbia University Press, 2000.

———. Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex.” New York: Routledge, 1993.

———. Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative. New York: Routledge, 1997.

———. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge, 1990.

———. “Intitation and Gender Insubordination.” In The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader, ed. Henry Abelove, Michèle Aina Barale, and David M. Halperin, 307-21. New York: Routledge, 1993.

———. The Psychic Life of Power: Theories in Subjection. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997.

———. Subjects of Desire: Hegelian Reflections in Twentieth-Century France. New York: Columbia University Press, 1987.

Butler, Judith, Ernesto Laclau, and Slavoj Zizek. Contingency, Hegemony, Universality: Contemporary Dialogues on the Left. London: Verso, 2000.

Butler, Judith, and Joan Wallach, eds. Feminists Theorize the Political. New York: Routledge, 1992.

Cadava, Eduardo, Peter Connor, and Jean-Luc Nancy, eds. Who Comes after the Subject? New York: Routledge, 1991.

Califia, Pat. Sex Changes: The Politics of Transgenderism. San Francisco: Cleis Press, 1997.

Champagne, Rosaria. “Queering the Unconscious.” South Atlantic Quarterly 97 (1998): 281-97.

Cheah, Pheng. “Mattering.” Review of Bodies that Matter, by Judith Butler, and Volatile Bodies, by Elizabeth Grosz. Diacritics 26 (1996): 108-39.

Clark, Eric O. Virtuous Vice: Homoeroticism in the Public Sphere. Durham: Duke University Press, 2000.

Comstock, Gary David, and Susan E. Henking eds. Que(e)rying Religion: A Critical Anthology. New York: Continuum, 1997.

Copjec, Joan, ed. Supposing the Subject. London: Verso, 1995.

Crimp, Douglas, and Adam Rolston, AIDS Demo Graphics. Seattle: Bay Press, 1990.

David-Menard, Monique, ed. Feminist Interpretations of Immanuel Kant. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997.

de Lauretis, Teresa. “Queer Theory: Lesbian and Gay Sexualities.” differences: a Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies. 3, no. 2 (1991): iii-xviii

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1983.

———. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

D’Emilio, John, and Estelle Freedman. Intimate Matters: A History of Sexuality in America. New York: Harper & Row, 1988.

———. The World Turned: Essays on Gay History, Politics, and Culture Durham: Duke University Press, 2002.

Diacritics

differences: a Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies.

DiPiero, Thomas. White Men Aren’t. Durham: Duke University Press, 2002.

Dollmore, Jonathan. Sexual Dissidence: Ausgutine to Wilde, Freud to Foucault. Oxford: Clarendon, 1991.

Duberman, Martin, ed. A Queer World: The Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader. New York: New York University Press, 1997.

Duberman, Martin B., Martha Vincus, and George Chauncey, eds. Hidden from History, New York: NAL, 1989.

Duggan, Lisa. “Theory in Practice: The Theory Wars, or, Who’s Afraid of Judith Butler?” Journal of Women’s History 10, no. 1 (1998): 9-19.

Dynes, Wayne, ed. Encyclopedia of Hornosexuality, 2 vols. Garden City, NY: Garland, 1989.

Dynes, Wayne, and Stephen Donaldson, eds. History of Homosexuality in Europe and America. New York: Garland, 1992.

Edelman, Lee. Homographesis. New York: Routledge University Press, 1994.

———. “Queer Theory: Unstating Desire.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 2, no. 4 (1995): 343-46.

———. “Tearooms and Sympathy, or, The Epistemology of the Water Closet.” In Nationalisms and Sexualities, eds. Andrew Parker et al., 263-85. New York: Routledge, 1992.

Evans, David T. Sexual Citizenship: The Material Construction of Sexualities. New York: Routledge, 1993.

Faderman, Lilian. Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers: A History of Lesbian Life in Twentieth-Century America. New York: Columbia University Press, 1990.

Faderman, Lilian, and Brigette Erikson. Lesbian-Feminism in Turn-of-the-Century Germany. Weatherby Lake, MO Naiad Press, 1980.

Fausto-Sterling, Anne. Myths of Gender: Biological Theories about Women and Men. New York: Basic Books, 1992.

Foucault, Michel. Ethics: Subjectivity and Truth. New York: New Press, 1994.

———. The Foucault Effect: Studies in Govemmentality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991.

———. The History of Sexuality. 3 vols. New York: Vintage Books, 1980.

———. Remarks on Marx: Conversations with Duccio Trombadori. New York: Semiotext(e), 1991.

———. “What is Enlightenment.” In The Foucault Reader, ed. Paul Rabinow. New York: Pantheon, 1984.

Fout, John C. A Select Bibliography on the History of Sexuality. Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: Committee on Lesbian and Gay History, Bard College, 1989.

Fout, John C., ed. Forbidden History: The State, Society, and the Regulation of Sexuality in Modern Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

Garber, Marjorie. Vested Interests: Cross-Dressing and Cultural Anxiety. London: Routledge, 1992.

Gerard, Kent, and Gert Hekma, eds. The Pursuit of Sodomy: Male Homosexuality in Renaissance and Enlightenment Europe. New York: Harrington Park Press, 1989.

GLQ

Gluckman, Amy, and Betsy Reed, eds. Homo Economics: Capitalism, Community and Lesbian and Gay Life. New York: Routledge, 1997.

Goldberg, Jonathan, ed. Queering the Renaissance. Durham: Duke University Press, 1994.

Greenberg, David E The Construction of Homosexuality. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1988.

Grosz, Elizabeth. Space, Time, and Perversion. Essays on the Politics of Bodies. New York: Routledge, 1995.

———. Volatile Bodies. Toward a Corporeal Feminism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994.

Halle, Randall. Queer Social Philosophy: Critical Readings from Kant to Adorno. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2004.

Haraway, Donna. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge, 1991.

Hekma, Gert, Harry Oosterhuis, and James Steakley, eds. Gay Men and the Sexual History of the Political Left. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press, 1995.

Hennessy, Rosemary. “Incorporating Queer Theory on the Left.” In Marxism in the Postmodern Age: Confronting the New World Order, ed. Antonio Callari, Stephen Cullenberg, and Carole Biewener. New York: Guilford Press, 1995.

Herdt, Gilbert, ed. Third Sex, Third Gender: Beyond Sexual Dimorphism in Culture and History. New York: Zone Books, 1994.

Herzer, Manfred. Bibliographic zur Homosexualitat: Verzeichnis des deutschsprachigen nichtbelletristischen Schrifttums zur weiblichen und mannlichen Homosexualitat: aus deu Jahren 1466 bis 1975. Berlin: Winkel, 1982.

Hull, Isabel V Sexuality, State, and Civil Society in Germany, 1700-1815. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1996.

Jagose, Annamarie. Queer Theory: An Introduction. New York: New York University Press, 1997.

Journal of the History of Sexuality

Journal of Homosexuality

Katz, Jonathan Ned. The Invention of Heterosexuality. New York: Dutton, 1995.

Kennedy, Ellen, and Susan Mendus, eds. Women in Western Political Philosophy: Kant to Nietzsche. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1987.

Kuzniar, Alice A., ed. Outing Goethe and His Age. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996.

Lancaster, Roger, and Micaela di Leonardo, eds. The Gender/Sexuality Reader: Culture, History, Political Economy. New York: Routledge: 1997.

Phelan, Shane. “The Shape of Queer: Assimilation and Articulation.” Women and Politics 18, no. 2 (1997): 55-73.

Martin, Carolyn Biddy. Femininity Played Straight: The Significance of Being Lesbian. New York: Routledge, 1996.

Meer, Theo van der, and Anja van Kooten Niekerk, eds. Homosexuality. Which Homosexuality? International Scientific Conference on Gay and Lesbian Studies. Amsterdam/ London: An Dekker/Gay Men’s Press, 1989.

Pateman, Carole, and Mary Lyndon Shanley eds. Feminist Interpretations and Political Theory. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1991.

Plummer, Kenneth, ed. The Making of the Modern Homosexual. London: Hutchinson, 1981.

Raffo, Susan, ed. Queerly Classed. Boston: South End Press, 1997.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire. New York: Columbia University Press, 1985.

———. Epistmology of the Closet. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

———. Prformativity and Perforrnance. New York: Routledge, 1995.

———. Tendencies. New York: Routledge, 1994.

Signs

Silverman, Hugh. Philosophy and Desire. New York: Routledge, 2000.

Silverman, Kaja. Male Subjectivity at the Margins. New York: Routledge, 1992.

Snitow, Ann, Christin Stansell, and Sharon Thompson, eds. Powers of Desire: The Politics of Sexuality. New York: New Feminist Library, 1983.

Steakley, James. The Homosexual Emancipation Movement in Germany. New York: Arno, 1975.

Stein, Edward, ed. Forms of Desire: Sexual Orientation and the Social Constructionist Controversy. New York: Routledge, 1992.

Tobin, Robert. Warm Brothers: Queer Theory and the Age of Goethe. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000.