Five

Constructivism and the Logic of Legitimation

Stacie E. Goddard

Ronald R. Krebs

Over the past decade scholars associated with diverse research traditions increasingly have agreed that legitimacy matters to the theory and practice of world politics. It is not surprising that constructivists, sensitive to the social fabric of international life, would see legitimacy as central even to the high politics of diplomacy and threat assessment. We would expect constructivists to highlight how states strive to frame even their deviant foreign policy behaviors as consistent with dominant norms and how norm violators seem especially menacing.1 But it is more surprising that realists and liberal rationalists too now argue that states generally value their reputation for being upstanding, rule-following members of the international community. Realists acknowledge that hegemony that rests on coercion alone is expensive and that legitimacy greases the wheels of global rule.2 Liberal rationalists similarly argue that insofar as abiding by or violating global norms can be costly, legitimate and illegitimate behavior potentially reveal a state’s “type.”3

Despite the field’s embrace of legitimacy, scholars of international relations have shown less interest in the politics of legitimation: how political actors publicly justify policy stances before concrete audiences, seeking to secure audiences’ assent that their positions are indeed legitimate and thus potentially to garner audiences’ approval and support.4 Even scholars who see legitimacy as integral to world politics often pay little attention to the rhetoric that gives rise to it. Some dismiss such rhetoric as meaningless posturing, as mere window dressing masking interests and power. For realists, leaders deploy rhetoric to manipulate and mobilize the credulous masses, who seem always to fall for the ethnic cards they play and for the myths of empire they propagate.5 For liberal rationalists, leaders’ public rhetoric might help overcome secrecy’s deleterious consequences, but only if uttering the words or eventually violating those commitments is sufficiently costly that it reveals true interests and actual will.6 Even mainstream constructivists have shown more interest in how already legitimate norms and ideas drive and constrain foreign policy than in how actors go about rendering particular policies legitimate.7

The field’s legitimation blind spot is puzzling. If legitimacy matters, so too must legitimation: action can be legitimate only if actors claim legitimacy and only if audiences grant those claims. Moreover, much of the empirical substance of world politics revolves around legitimation contests: dizzying public claims, counterclaims, and counter-counterclaims with respect to the legitimacy, and not merely the wisdom or advisability, of policy. Political actors the world over—from politicians to pundits to activists—devote substantial resources, energy, and political capital to rhetorical battle. They implicitly recognize that legitimation shapes the fate of political projects, from the welfare state to national security. To overlook legitimation is to overlook much of global politics. For these reasons, this chapter urges constructivists to take a public rhetorical turn and to make legitimation central to the study of international relations and foreign policy.

As we have already suggested, card-carrying social constructivists are not the only ones who should be attentive to legitimation. It should be a concern for all scholars of international relations who invoke notions of legitimate action. But that, in our view, is because any account that takes legitimacy seriously—in that it refuses to reduce standards of legitimacy to the interests, resources, and beliefs of individual actors and further that it sees those standards as shaping the behavior of even the materially and institutionally powerful—rests on social constructivist premises about the nature of the world, or ontology. A constructivist perspective sees politics as a contest not just over the distribution of material resources, but over social meaning, over how we make public sense of events and action. Constructivist accounts normally invoke social phenomenona—norms, identities, rules—that embody specific constellations of meaning and define the boundaries of legitimate political action. When these contingent constellations become sufficiently institutionalized and sedimented, they acquire the status of background common sense, to the point that they seem natural, timeless, and beyond the political realm; that is, they become social facts.8 When realists and liberal rationalists invoke legitimacy as an independent causal force in international relations and foreign policy, they are at the very least smuggling in, if not openly conceding, social constructivist insights. As will become clear below, however, we do not see constructivism as at odds with either strategic action or the operation of power. On the one hand, the social processes that give rise to the boundaries of legitimation necessarily entail power, albeit in a constitutive and sometimes indirect form.9 On the other hand, we oppose the common effort to assign human action to either the logic of instrumentalism or the logic of appropriateness and to associate the former with constructivism. Such an analytical move obscures how social standards are intertwined with, make possible, and confine rational action.10

The rest of this chapter proceeds in three sections. First, we define legitimation and clarify how a legitimation perspective differs from other approaches to public rhetoric in the field. Second, we specify the conditions under which legitimation affects political processes and outcomes: that is, when students of global politics should be particularly attentive to legitimation. Third, we conclude by laying out an agenda for future constructivist research on legitimation in international relations.

Legitimation as Concept and Perspective

By legitimation, we mean how political actors publicly justify their policy stances before concrete audiences. Our argument for making legitimation central to international relations theory derives from two premises regarding human nature: that human beings are both meaning-making and deeply social animals. A long line of research in the social sciences and humanities affirms that humans are compelled, perhaps even by nature, to imbue their own actions and those of others with meaning. That is why the human mind readily imposes an interpretive framework on disparate pieces of data, seeing order even when there is none.11 And that is why human beings are driven not only to describe what they have done but to explain why they have done it. Philosophers debate whether reasons are properly understood as causes for action, but providing reasons for our own actions, and making sense of others’ actions, is central to our existence.12 A more social imperative complements this internal one. Living in communities and craving their fellows’ approval, human beings are governed by what Elster has termed “the civilizing force of hypocrisy”: when we speak in public, we must offer socially acceptable reasons or face the censure of our peers.13

Moreover, there are few social settings in which legitimation does not prominently feature. Although exasperated parents may eventually command their children to “do as I say!” at even a fairly young age, children resist parental orders they think morally wrong or otherwise illegitimate.14 In hierarchical societies, the dominated—whether on the basis of class, ethnicity, caste, religion, or gender—refuse to grant legitimacy to their subordination.15 Superiors in a bureaucracy do at times issue orders without explaining themselves, but they too typically justify their decisions, to secure their underlings’ buy-in. Certainly the powerful, more often than the weak, can say patently absurd or contradictory things and still get their way. But in most social circumstances, even the powerful must explain themselves in terms that others comprehend and find acceptable. Those who do not care to legitimate their claims are rejected or ignored. At the extreme such an individual “is quickly regarded as a fanatic, the prey of interior demons, rather than as a reasonable person seeking to share his convictions.”16

It is because language imbues events and actions with meaning that legitimation is an imperative, not a mere nicety, of global politics.17 There are of course brute facts in the world. “The rise of China” is a prevalent trope in elite and popular discourse, but it does not exist solely in the linguistic realm: it encapsulates that nation’s rapid economic growth, urbanization, and military modernization.18 But processes of legitimation impart meaning to those material developments and thus shape how other nations respond. If China’s rise spoke for itself, as both defenders and critics of US foreign policy often imply, there would not be a vigorous debate over the implications of its rise for international and regional order. Because the meaning of global events and material structures is not self-evident—they “do not come with an instruction sheet,” as Blyth has put it—they cannot be treated as objective inputs into strategy.19 This is where legitimation comes in.

In arguing that legitimation should be front and center in constructivist theorizing, we are clearly indebted to and inspired by an earlier, critical linguistic turn in international relations that deconstructed authoritative texts to unearth the unarticulated “commonsense” assumptions that inform and structure policy. That literature rightly argued that the social could not be understood outside of language and that language is both the product of and productive of power. It insightfully placed the analysis of discourse at its center to reveal the exclusions and incoherence that are constitutive of identity.20 But, like many constructivists, we have found the critical linguistic turn unsatisfying in its refusal to engage causal dynamics and in its static presentation of dominant discursive structures that strip agency and politics out of the analysis. We thus opt for a “pragmatic” model of rhetorical politics that centers on specific rhetorical deployments in particular political and social contexts.21 This approach rests on four analytical wagers: that actors are both strategic and social, that legitimation works by imparting meaning to political action, that legitimation is laced through with contestation, and that the power of language emerges through contentious dialogue. In combination, these four wagers distinguish our pragmatic model from other approaches to language—critical and neopositivist, materialist and constructivist—common in the study of politics and international relations.

First, while we agree that political actors are often strategic, this does not mean that legitimation can be reduced to self-interest. Actors are embedded in a social environment that simultaneously makes possible and confines strategic action. Even scheming elites cannot stand outside structures of discourse. As these elites too are products of a given social milieu, the schemes they design must necessarily draw on their inherited “cultural tool-kit,” in Swidler’s words, which includes rhetorical resources.22 To conceive of speakers and audiences as social creatures is not to imagine them as cultural dopes, mindlessly following culture’s purported dictates. Rather, as they seek to make sense of their world, and as they respond to others’ meaning-making efforts, they are equally subject to, and empowered by, the shared resources embedded in their culture. This stands in contrast to the many realists who see public rhetoric as a mere fig leaf covering the naked pursuit of interest and who assume that elites easily bend the masses to their ends. It is not the case then that where there is a will, there must always be a rhetorical way.

Second, legitimation exerts effects on politics by imparting meaning to action. This model thus departs significantly from rationalist approaches to public rhetoric, which flatten language to a medium for the communication of information that, when costly, reveals such information to be credible. Rationalists thereby overlook the care with which speakers construct public arguments, audiences’ attention to rhetorical contest, and the ensuing intense debates over the interpretation of legitimation, over what a given speaker means and what it portends. A pragmatic approach emphasizes that whether public claims making is legitimate renders a signal meaningful, even if it does not entail material costs. How a nation’s central economic policymakers legitimate their policy stances demonstrates their competence to the global financial community, serves as a meaningful guide to their future behavior, or index,23 and shapes patterns of lending—even when their appointment or their articulation of policy is not especially costly.24 More important, by shaping public expectations, defining the issues at stake, distinguishing signals from noise, and laying the basis for debate, legitimation has constitutive effects in world politics. Whether leaders make legitimate sense of their nations’ actions affects whether other states deem them benign or aggressive: security threats are constructed, not merely revealed, in the course of legitimation. Whether actors succeed in legitimating their private agendas affects whether their aims are thought cosmopolitan (that is, in the interest of the global community), parochial (that is, in the interests of domestic groups), or in the service of the nation’s long-term welfare. Legitimation is thus essential to the production of the national interest. The rationalist bargaining model has seized upon one aspect of the dynamics of public rhetoric, while overlooking its much more fundamental role in the making of meaning in global politics.

Third, compared to many constructivist accounts, we conceive of political actors as less socialized and more strategic. Constructivists informed by the discourse ethics of Habermas have viewed persuasive rhetoric as central to normative change in international relations, and they have argued that persuasion is most likely when speakers and listeners are both committed to the open exchange of ideas.25 While Habermas recognizes that politics is often a site of strategic action, he envisions and directs humanity toward a politics in which power and rank are left at the door, in which agonistic competition is replaced by deliberation and ultimately by consensus. Our pragmatic model, in contrast, theorizes language use as necessarily deeply shot through with power and marked by contest. Moreover, we do not presuppose universal standards by which audiences judge arguments persuasive. In Habermas’s account, actors can be moved by the “unforced force of the better argument,” but this presumes that they are already in agreement on fundamentals, that they have already attained substantial zones of consensus.26 We, however, see legitimation as taking place before particular, not universal, audiences, and claimants adapt to the audience’s “distinctive and particular passions and their particular commitments, sentiments, and beliefs.”27

Finally, a pragmatic model of legitimation rests on a dialogical view of politics, in which various articulations compete for dominance. Scholars associated with the aforementioned critical linguistic turn in international relations point out, following Foucault, how discursive formations define the key categories of social and political life and thus constitute the range of legitimate politics. We concur with their foundational insight that discourse is both the product of, and productive of, power. But we take issue with their implicit assertion, in Neumann’s formulation, that “there is nothing outside of discourse and, for this reason, the analysis of language is all that we need in order to account for what is going on in the world.”28 Rather, legitimation proves powerful through a complex interplay between text and context, between what is said and where and when it is said. Existing discursive formations do not eliminate all space for choice and contingency, and thus agency.

Scholars of international relations routinely treat legitimation as a mask for power and interests, cast legitimation as an idealized alternative to power, reduce public rhetoric’s effects to revealing information, or see public rhetoric as an exercise in manipulation. To place one’s analytical bets on legitimation as pragmatic performance is not to deny that rhetorical exchange takes place in the shadow of material power, reflects elite strategizing, or involves the communication of information. It is, however, to insist that legitimation is a form of power, that strategizing elites cannot escape the bonds of legitimacy, that rhetorical exchange goes beyond signaling resolve and reservation values, and that the outcome of rhetorical contestation cannot be boiled down to the distribution of material power alone. Legitimation, in our view, neither competes with nor complements power politics: it is power politics.29 Triumph in the public contest over social meaning affects the distribution of capabilities, actor identities, and even their visions of political possibilities. It marginalizes some voices, rendering them effectively silent, while it empowers others to effect political change. Those who cannot legitimate their preferred strategy are, as Hans Morgenthau long ago argued, “at a great, perhaps decisive, disadvantage in the struggle for power.”30

When Legitimation Matters

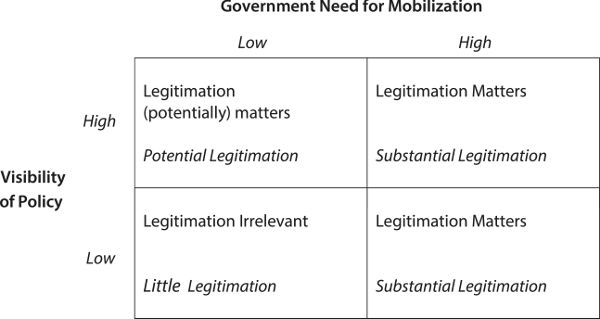

Legitimation is so commonplace that we might be tempted to conclude that it is of little consequence in accounting for variation in political processes and outcomes. Part of the analytical challenge is to ascertain when legitimation matters: when must global actors attempt to legitimate their actions to domestic or international audiences, and when do their efforts at legitimation, and their diverse strategies, have powerful effects, both causal and constitutive? At the most basic level, we contend that legitimation is necessary whenever publics, be they domestic or global, must be mobilized, and it lurks in the background wherever there is a reasonable chance that the glare of attention will turn. Put differently, the political impact of legitimation lies at the intersection of two demands: some important public’s demand for legitimation, or the visibility of a policy domain, and the government’s demand for some public’s contribution, or the need for mobilization.

Audiences’ insistence that officials explain themselves is a key driver of legitimation. If relevant publics are inattentive, if they are unlikely to be made to pay attention, and if the policy in question can be hidden from public view, legitimation is not necessary. Much escapes public scrutiny in large bureaucratic nation-states thanks to the public’s and the media’s wavering attention, the technical sophistication of policy, legislatures’ inclination to delegate, the broad scope of state activity, and the sheer size of the bureaucracy. Yet policy must generally be capable of legitimation: policies that domestic and global publics at first ignore may subsequently come into their crosshairs, and even those policies that government officials go to lengths to keep secret may eventually come to light and prove highly controversial—as recent scandals over National Security Agency spying in the United States and over CIA-led torture of terrorist suspects have reminded us. Politicians prefer covert means when they cannot offer a rationale that audiences would deem legitimate, but covert actions rarely remain covert forever, and sometimes not for long at all, and they then require justification after the fact. Russia’s denial that its forces secretly had intervened in the Ukrainian civil war in 2014 was unusual only in its audacity. With the world’s, and notably NATO’s, attention fixed on the Ukraine crisis, Russia’s steadfast refusal to acknowledge the full extent of its involvement and to provide public justification for its seeming violation of international norms ensured that its activities enjoyed little legitimacy outside Russia.

Government officials, however, do not have incentives to keep invisible as much of the policy space as possible. Governments often need to mobilize domestic publics, for both tangible resources and symbolic support, and they would rather people willingly contribute the needed resources. That requires engaging relevant publics, not shutting them out of the policymaking process, and thus legitimation, not coercion. The more extensive and regular the government’s needs, the more institutionalized legitimation becomes. Thus the roots of representative parliamentary institutions and the machinery of liberal politics lie, Tilly argues, in European states’ need to mobilize resources for war making.31 The greater government’s demand for resources, the greater its need to engage in legitimation.

This same logic extends, albeit incompletely, to international relations, where the grounds for legitimation are often more uncertain and contested. Insofar as states require international cooperation, they must engage in legitimation to some foreign audience, whether other state leaders or mass publics. International institutions, in particular, can increase the demand for legitimation and thus exert effects on behavior, even when their powers of punishment and socialization are weak. This was true, Mitzen argues, of the Concert of Europe, which required European statesmen to legitimate their stances in the language of shared European norms, made it less likely they would openly invoke self-interest, and thereby compelled them to act contrary to their interests and even helped them to redefine their interests; via the logic of legitimation, the Concert forestalled Russian intervention in the Greek Revolt.32 It was even true of the League of Nations, which, despite being a notoriously weak organization, sustained the international community’s demand that Japan legitimate its invasion of Manchuria; when its answers proved unsatisfactory, Japan left the League of Nations. The more extensive and regular are states’ needs for international cooperation, the more institutionalized legitimation becomes, as reflected in NATO’s governing arrangements that provided for deep consultation among the allies and that, to an extent, mitigated inequalities of power.33 At times, state leaders may even attempt to justify their behavior to the foreign masses, as Russia’s Vladimir Putin sought in a New York Times op-ed in September 2013.

In figure 5.1, we combine these two dimensions to generate claims about when legitimation matters. Legitimation is obviously crucial in the upper-right cell, when policies are highly visible and when the government must mobilize public support. We then should observe substantial government-led efforts to legitimate its preferred policy, and the success of those efforts will have real consequences, or the government would not have expended resources on legitimation in the first place. These dynamics are, for instance, typical of the years of rivalry and crisis that precede major interstate war, and they affect whether, and how effectively, the home front is mobilized and alliances are brought to bear. But the government’s success is not assured. When policy is highly visible, it is then also more likely that political forces are arrayed in opposition and that alternative legitimations are present in the public sphere.

In contrast, legitimation matters little in the lower-left cell, when policies are relatively invisible and when government has little incentive to mobilize public resources. With audiences inattentive or unaware, and with government not requiring overt expressions or manifestations of legitimacy, government-led efforts to legitimate policy are expected to be minimal. In relatively open polities and international regimes, challenges are inevitable, but under circumstances of low visibility and mobilization, these are fewer in number and lower in intensity and hail from the margins, and officials, feeling little pressure to take critics seriously, respond in relatively perfunctory fashion. Think, for instance, of the spare efforts among US officials to legitimate the establishment and maintenance of hundreds of military installations around the world: US ambassadors exert far more energy defending these bases to host audiences than their domestic counterparts must at home. Or consider covert operations, from the arming of rebels to the assassination of foreign leaders, for which public legitimation is irrelevant, at least temporarily. But this zone, we argue, is fairly small because government must always account for the possibility that outside actors—from domestic and transnational nongovernmental organizations to foreign and opposition politicians—will work to increase an issue’s visibility and thus that newly attentive publics will demand legitimation in retrospect.

Many policy issues, however, fall into the other two cells of figure 5.1. In the lower-right cell, the public is not focused on a given issue, yet the government requires major public contributions for policy to succeed. The purpose of legitimation under these conditions is to set the public agenda, to get people to pay attention. Consider, for instance, the strategic efforts of governments, and sometimes groups in national and transnational civil society, to raise the profile of particular threats. This is as true of routine threat construction as it is of so-called threat inflation. There are numerous ways to render a policy domain publicly visible, but it is hard to imagine doing so without a sustained campaign of legitimation, as Dean Acheson understood early in the Cold War when he helped craft Harry Truman’s case for aid to Greece and Turkey in dramatic terms; as environmentalists understood when they sought to awaken mass publics and policymakers to the dangers of climate change; and as transnational activists aiming to ban chemical arms and landmines understood when they profiled these weapons’ innocent and unintended victims. The strategy and style of legitimation during this agenda-setting phase sets boundary constraints for subsequent legitimation once the issue has already seized the public’s attention. Whether there are powerful rhetorical “consistency constraints” at work in the political arena is much debated, and indeed the empirical jury is still out, but they would seem most likely to operate in the wake of a concerted campaign to shape the national conversation. This cell then is usually not a stable equilibrium. As an issue’s visibility rises, politics migrates toward the upper-right cell.

In the upper-left cell of figure 5.1—when the visibility of an issue is high, yet the government’s demand for public contribution is low—the degree of observed legitimation is contingent. Not needing much public mobilization, the government has no incentive to engage in regular legitimation. Many episodes of coercive diplomacy fall into this category. So too has the US drone strike campaign of recent years in such places as Pakistan and Yemen. But often policy opponents will choose to make this a site of challenge, whether out of principle or because they see potential for political profit, as has been the case with respect to drone warfare. Moreover, under the watchful eye of civil society, officials must be ready to justify policy and thus have strong incentives to avoid flagrantly illegitimate behavior. Policies in this zone may then not be the subject of active official legitimation, but they must always be capable of legitimation.

While legitimation is nearly ubiquitous, it does not always play a signal causal role in foreign policy and international relations. It matters most, we maintain, when officials need to mobilize resources—from either domestic or foreign audiences, whether mass or elite—and when relevant publics are attentive. Much of the politics of foreign policy thus revolves around the politics of visibility, as government officials and their opponents seek to define the scope of the audience for legitimation. Officials seek to confine issue awareness to public audiences before whom legitimation is possible and to keep issues out of the public eye when their legitimation would be difficult. Opponents in both the halls of power and civil society seek to broaden the audience to the point that legitimation becomes challenging. By rendering policy visible, they hope to compel officials to justify what cannot be justified and ideally force government into a rhetorical vise.34

Legitimation and the Future of Constructivism

While scholars across the field of international relations have acknowledged the power of legitimacy, the concept is most central to the constructivist tradition. Legitimacy refers to the boundaries of the acceptable within a given social community, and it therefore sets out the limits of sustainable social practice. Among international relations’ diverse research traditions, constructivists most fully trace the implications of the international as a social realm, and it is thus no surprise that constructivists would see legitimacy as especially important. But, perhaps because constructivists have emphasized ideas and norms, they have devoted less attention to legitimation— that is, to the public rhetorical practices through which actors seek to cultivate legitimacy, to draw and redraw its boundaries, and to produce political effects. We have only a dim understanding of how political actors engage in legitimation, and with what consequences, in different domains. And we have even less understanding of how contests of legitimation play out, why political debate is sometimes wide-ranging and sometimes proceeds on a narrow foundation, why certain rhetorical formulations are transformed into background common sense while others remain subject to open challenge.35 This chapter’s ambition has been less to resolve long-standing questions and summarize the existing scholarly wisdom than to open a conversation and invite new lines of research.

This chapter has left at least three significant questions unanswered, which point to starting points for future constructivist research into the politics of legitimation. First, in the section above, we treated the model’s two dimensions—the visibility of policy and the government’s need for mobilization—largely as untheorized, exogenous inputs. If constructivists are to understand when legitimation shapes political processes and outcomes, this requires determining the concrete circumstances under which policies are likely to become visible and when publics must be mobilized. For instance, the broader the scope of policy, the more important legitimation is for its success. Officials can, and often seek to, keep fine-grained matters out of the public eye, but that is not possible when it comes to policies of broad scope, which are intrinsically visible because they impact so many constituencies and often require substantial mobilization. This implies that officials are more likely to have to legitimate, say, grand strategy than more mundane areas of policy, domestic or foreign. Even more counterintuitively, it further follows that the more private interests stand to gain or lose from the adoption of a particular policy, the more legitimation determines actors’ success. The more clearly interests are at stake in foreign policy, and the more substantial those interests are, the more others expect these private interests to seek to turn the machinery of government to their own ends, and the greater the scrutiny to which they subject policy proposals. The more divided the contending interests, the greater the need to mobilize the public, and the more political success hinges on a resonant rhetoric that can mobilize a winning coalition. This line of reasoning might be followed to explore how the threat environment, regime type, density and strength of international institutions, and other factors shape the significance of legitimation in particular domains of world politics.36

Second, we have alluded to, but not theorized, the outcome of legitimation contests. If legitimation is a war of words, what distinguishes the winners from the losers of a rhetorical battle? Why are some efforts more successful than others in specific policy domains? While processes of legitimation are in principle open—anyone can attempt to legitimate using whatever language they would like—a pragmatic model of legitimation suggests, as Williams argues, that “in practice [they are] structured by the differential capacity of actors to make socially effective claims[,] . . . by the forms in which these claims can be made in order to be recognized and accepted as convincing by the relevant audience, and by the empirical factors or situations to which these actors can make reference.”37 In other words, explaining rhetorical power cannot just be a matter of conforming to the linguistic rules of a given domain, as seminal work on securitization emphasized.38

Broadly speaking, and drawing from more recent agenda-setting work on securitization, it seems that five factors shape which legitimation attempts succeed and which fail: (1) who speaks, (2) where and when they say it, (3) to whom they say it, (4) what they say, and (5) how they say it.39 (1) Some speakers have authority to legitimate policy, while others shout from the sidelines. Some enjoy credibility as spokespersons for the public interest, while others are dismissed as self-serving. (2) Context matters as well to whether legitimation is required and is politically significant and to how legitimation contests play out. On the one hand, institutional rules may shape the authority and capacity of speakers. On the other hand, discursive structures can be so tight that all legitimation is confined to a dominant discourse, which renders some policy stances indefensible, or they can permit a far broader range of legitimation strategies and policy stances. (3) Audiences are central to rhetorical battle, for it is they who determine the victor. Contestants’ capacity to craft resonant legitimations presumably depends on various features of relevant audiences: the nature of their interests, their unity or diversity, their education and political sophistication. (4) The content of legitimating appeals affects their persuasiveness. It is well established that when deployed frames draw on and are consistent with common rhetorical formulations, they are more likely to resonate than when these frames sit in tension with audiences’ rhetorical priors. (5) The fate of legitimation rests also on rhetorical technique. Speakers strike audiences as skilled based in part on what metaphors, analogies, figures of speech, and tone they choose, as well as how they conform to the rhetorical conventions associated with particular forms of public address or genres. Audiences respond differently under different circumstances and to different rhetorical modes, whether speakers offer argument or whether they tell compelling stories.40

These five baskets of factors shape the outcome of legitimation contests, but the literature lacks many well-limned causal claims with well-conceptualized variables and appropriate scope conditions. Future research has far to go in unpacking these broad baskets, specifying the conditions under which particular factors operate, and spelling out what effects they produce.

Third, and finally, the effects of legitimation are not constant through time and space. They vary along with developments in technologies of communications and information, which in turn bolster (or undermine) authority, enlarge (or shrink) audiences, polarize (or unify) those audiences, make policy more (or less) visible, and increase (or diminish) the demand for legitimation. Theorizing and examining empirically how recent and historical changes in the material and social context of communication have shaped the intensity and dynamics of legitimation is a tall order for future research, but an essential one if we are to make sense of leadership in the contemporary age.41

Notes

Portions of this chapter draw from our contribution to a special issue on “Rhetoric and Grand Strategy.” Stacie E. Goddard and Ronald R. Krebs, “Rhetoric, Legitimation, and Grand Strategy,” Security Studies 24, no. 1 (Jan.–March 2015): 5–36.

1. Ian Hurd, After Anarchy: Legitimacy and Power in the United Nations Security Council (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007); Christian Reus-Smit, American Power and World Order (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2004), 102; Mlada Bukovansky, Legitimacy and Power Politics: The American and French Revolutions in International Political Culture (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002). On legitimacy and global politics, see generally Ian Clark, Legitimacy in International Society (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007); and Ian Hurd, “Legitimacy and Authority in International Politics,” International Organization 53, no. 2 (Spring 1999).

2. Stephen G. Brooks and William C. Wohlforth, World Out of Balance: International Relations and the Challenge of American Primacy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008), 207.

3. On rhetoric and signaling, see Jack L. Goldsmith and Eric A. Posner, “Moral and Legal Rhetoric in International Relations: A Rational Choice Perspective,” Journal of Legal Studies 31, no. 1 (January 2002): esp. 123–25.

4. On the distinction between legitimacy and legitimation, see Rodney Barker, Legitimating Identities: The Self-Presentations of Rulers and Subjects (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 1–29.

5. Jack L. Snyder, Myths of Empire: Domestic Politics and International Ambition (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991); Jack L. Snyder and Karen Ballentine, “Nationalism and the Marketplace of Ideas,” International Security 21, no. 2 (Fall 1996): 5–40; and John J. Mearsheimer, Why Leaders Lie: The Truth about Lying in International Politics (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011). For a neoclassical realist exception, see Randall L. Schweller, Unanswered Threats: Political Constraints on the Balance of Power (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006).

6. On public commitments, credibility, and audience costs, see, among a very large literature, James D. Fearon, “Domestic Political Audiences and the Escalation of International Disputes,” American Political Science Review 88, no. 3 (1994): 577–92; Anne E. Sartori, “The Might of the Pen: A Reputational Theory of Communication in International Disputes,” International Organization 56, no. 1 (Winter 2002): 121–49; and Charles Lipson, Reliable Partners: How Democracies Have Made a Separate Peace (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005).

7. However, on normative change, see Neta Crawford, Argument and Change in World Politics: Ethics, Decolonization, and Humanitarian Intervention (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002); Martha Finnemore, The Purpose of Intervention: Changing Beliefs About the Use of Force (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2003); Richard Price, “Reversing the Gun Sights: Transnational Civil Society Targets Land Mines,” International Organization 52, no. 3 (Summer 1998): 613–44; Nina Tannenwald, The Nuclear Taboo: The United States and the Non-Use of Nuclear Weapons Since 1945 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007). There is also a large, relevant literature on the legitimation of global institutions: see, among others, Jens Steffek, “The Legitimation of International Governance: A Discourse Approach,” European Journal of International Relations 9, no. 2 (June 2003): 249–75; Achim Hurrelmann et al., eds., Legitimacy in an Age of Global Politics (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007); Dominik Zaum, ed., Legitimating International Organizations (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

8. On social facts, see Emile Durkheim The Rules of Sociological Method, ed. Steven Lukes (New York: Free Press, 1982); John R Searle, The Construction of Social Reality (New York: Free Press, 1995).

9. This is the form of power that Michael N. Barnett and Raymond Duvall term “productive.” See Barnett and Duvall, “Power in International Politics,” International Organization 59, no. 1 (Winter 2005), 39–76.

10. On these logics, see James G. March and Johan Olsen, Rediscovering Institutions: The Organizational Basis of Politics (New York: Free Press, 1989); and for an application to international relations, see Martha Finnemore and Kathryn Sikkink, “International Norm Dynamics and Political Change,” International Organization 52, no. 4 (1998): 887–917. For a critique, see Ole Jacob Sending, “Constitution, Choice and Change: Problems with the ‘Logic of Appropriateness’ and Its Use in Constructivist Theory,” European Journal of International Relations 8, no. 4 (2002): 443–70.

11. On the human penchant for imposing cognitive order, see Thomas Gilovich, How We Know What Isn’t So: The Fallibility of Human Reason in Everyday Life (New York: Free Press, 1991), esp. 9–28; Arie W. Kruglanski, The Psychology of Closed Mindedness (New York: Psychology Press, 2004); Leonid Perlovsky, “Language and Cognition,” Neural Networks 22, no. 3 (April 2009): 247–57; Richard M. Sorrentino and Christopher J. R. Roney, The Uncertain Mind: Individual Differences in Facing the Unknown (Philadelphia: Psychology Press, 2000).

12. The seminal philosophical work is Donald Davidson, “Actions, Reasons, and Causes,” Journal of Philosophy 60, no. 23 (November 1963): 685–700. On the centrality of reason giving in practice, see Charles Tilly, Why? What Happens When People Give Reasons . . . and Why (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008).

13. Jon Elster, “Deliberation and Constitution-Making,” in Deliberative Democracy, ed. Jon Elster (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 104.

14. Serena A. Perkins and Elliot Turiel, “To Lie or Not to Lie: To Whom and Under What Circumstances,” Child Development 78, no. 2 (March–April 2007): 609–21; Elliott Turiel, The Culture of Morality: Social Development, Context, and Conflict (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), esp. 107–18; Elliott Turiel, “Moral Development,” in Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science, Volume 1: Theory & Method, ed. William F. Overton and Peter C. Molenaar (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2014).

15. See James C. Scott, Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1985): for a psychological perspective, Turiel, The Culture of Morality, esp. 67–93.

16. Chaïm Perelman, The Realm of Rhetoric (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1982), 16.

17. Generally, on the imperative to legitimation, see Jon Elster, “Strategic Uses of Argument,” in Barriers to Conflict Resolution, ed. Kenneth Arrow et al. (New York: Norton, 1995), 244–52; Mark C. Suchman, “Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches,” Academy of Management Review 20, no. 3 (July 1995): 571–610.

18. Though those too are bulky concepts, resting on layers of sedimented meanings. They are, however, shorthand for concrete processes: goods being manufactured and sold, people moving from villages to cities, capital-intensive weaponry being acquired.

19. Mark Blyth, “Structures Do Not Come with an Instruction Sheet: Interests, Ideas, and Progress in Political Science,” Perspectives on Politics 1, no. 4 (December 2003): 695–706.

20. See, among many others, Michael J. Shapiro, Language and Political Understanding: The Politics of Discursive Practices (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1981); James Der Derian and Michael J. Shapiro, eds., International/Intertextual Relations: Postmodern Readings of World Politics (Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1989); David Campbell, Writing Security: United States Foreign Policy and the Politics of Identity, rev. ed. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998); Roxanne Lynn Doty, Imperial Encounters: The Politics of Representation in North-South Relations (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996).

21. See similarly Marie-Laure Ryan, “Toward a Definition of Narrative,” in The Cambridge Companion to Narrative, ed. David Herman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 25; Tine Hanrieder, “The False Promise of the Better Argument,” International Theory 3, no. 3 (November 2011): 409–10. On pragmatism and international relations, see Gunther Hellmann, “Pragmatism and International Relations,” International Studies Review 11, no. 3 (September 2009): 638–62; Jörg Friedrichs and Friedrich Kratochwil, “On Acting and Knowing: How Pragmatism Can Advance International Relations Research and Methodology,” International Organization 63, no. 4 (Fall 2009): 701–31.

22. Ann Swidler, “Culture in Action,” American Sociological Review 51, no. 2 (April 1986): 273–86.

23. Robert Jervis, The Logic of Images in International Relations, Morningside ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1989 [1970]).

24. For related supportive evidence, see Stephen C. Nelson, “Playing Favorites: How Shared Beliefs Shape the IMF’s Lending Decisions,” International Organization 68, no. 2 (May 2014): 297–328.

25. Thomas Risse, “‘Let’s Argue!’: Communicative Action in World Politics,” International Organization 54, no. 1 (Winter 2000): 1–39; Harald Müller, “International Relations as Communicative Action,” in Constructing International Relations: The Next Generation, ed. Karin M. Fierke and Knud Erik Jorgensen (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 2001); Marc Lynch, “Why Engage? China and the Logic of Communicative Engagement,” European Journal of International Relations 8, no. 2 (June 2002): 187–230. On the centrality of persuasion to much constructivist international relations scholarship, see Crawford, Argument and Change; Martha Finnemore, National Interests in International Society (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996), 141; Martha Finnemore and Kathryn Sikkink, “International Norm Dynamics and Political Change,” International Organization 52, no. 4 (Fall 1998): 914; Rodger A. Payne, “Persuasion, Frames and Norm Construction,” European Journal of International Relations 7, no. 1 (March 2001): 37–61.

26. Hanrieder, “The False Promise of the Better Argument.”

27. Bryan Garsten, Saving Persuasion: A Defense of Rhetoric and Judgment (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006), 5. See also Clark, Legitimacy in International Society, 254.

28. Iver B. Neumann, “Returning Practice to the Linguistic Turn: The Case of Diplomacy,” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 31, no. 3 (July 2002): 629.

29. Janice Bially Mattern, “The Concept of Power and the (Un)Discipline of International Relations,” in The Oxford Handbook of International Relations, ed. Christian Reus-Smit and Duncan Snidal (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 691–98.

30. Hans Morgenthau, Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace, 2nd ed. (New York: Knopf, 1954), 61–63.

31. Charles Tilly, Coercion, Capital, and European States, AD 990–1992 (Cambridge: Blackwell, 1992); Tilly, The Emergence of Citizenship in France and Elsewhere, International Review of Social History 40, supplement 3 (1995): 223–36. See also Stephen Holmes, “Lineages of the Rule of Law,” in Democracy and the Rule of Law, ed. José María Maravall and Adam Przeworski (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 19–61.

32. Jennifer Mitzen, Power in Concert: The Nineteenth-Century Origins of Global Governance (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013); Mitzen, “Illusion or Intention? Talking Grand Strategy into Existence,” Security Studies 24, no. 1 (Jan.–March 2015), 61–94.

33. Thomas Risse-Kappen, Cooperation Among Democracies: The European Influence on U.S. Foreign Policy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995).

34. On the mechanism of rhetorical coercion, see Ronald R. Krebs and Patrick T. Jackson, “Twisting Tongues and Twisting Arms: The Power of Political Rhetoric,” European Journal of International Relations 13, no. 1 (March 2007): 35–66; and Ronald R. Krebs, Fighting for Rights: Military Service and the Politics of Citizenship (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2006); Stacie E. Goddard, “When Right Makes Might: How Prussia Overturned the Balance of Power,” International Security 33, no. 3 (Winter 2008/2009): 110–42.

35. A wide range of scholarly traditions, despite differences in epistemological orientation and substantive concern, recognizes that some premises are unquestioned and strike participants and observers as common sense but are actually the product of human agency. See, among many others, Schattschneider’s classic insights into agenda setting, sociological accounts of political competition over the “definition of the situation,” Barthes’s efforts to demystify the naturalness that seemed to surround social myths, Bourdieu’s habitus that structures the everyday cultural forms through which subjects express themselves, Laclau’s writings on the establishment and disruption of doxa, and Foucault’s genealogies of institutional and disciplinary discourses.

36. We have done so with respect to legitimation and grand strategy in Goddard and Krebs, “Rhetoric, Legitimation, and Grand Strategy.”

37. Michael C. Williams, “Words, Images, Enemies: Securitization and International Politics,” International Studies Quarterly 47, no. 4 (December 2003): 514.

38. In his seminal theory of speech acts, Austin pointed out, rightly, that some utterances—such as saying “I do” at a wedding or making a promise—were themselves actions, and he argued that the key to their productive effect was their conformity to linguistic rules. This has found its way into international relations via theories of securitization. See John L. Austin, How To Do Things with Words, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1975). On securitization, see Barry Buzan et al., Security: A New Framework for Analysis (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 1998); Thierry Balzacq, ed., Securitization Theory: How Security Problems Emerge and Dissolve (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2011).

39. See, similarly, Holger Stritzel, “Towards a Theory of Securitization: Copenhagen and Beyond,” European Journal of International Relations 13, no. 3 (September 2007): 357–83; Thierry Balzacq, “The Three Faces of Securitization: Political Agency, Audience and Context,” European Journal of International Relations 11, no. 2 (June 2005): 171–201.

40. For exploration of these dynamics, see Ronald R. Krebs, Narrative and the Making of U.S. National Security (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015); Krebs, “How Dominant Narratives Rise and Fall: Military Conflict, Politics, and the Cold War Consensus,” International Organization 69, no. 4 (Fall 2015): 809–45; Krebs, “Tell Me a Story: FDR, Narrative, and the Making of the Second World War,” Security Studies 24, no. 1 (January–March 2015): 131–70; Stacie E. Goddard, When Right Makes Might: Rising Powers and World Order (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, forthcoming).

41. For preliminary efforts along these lines, see Ronald R. Krebs, “Pity the President,” The National Interest 148 (March/April 2017): 34–42; and Krebs, “The Politics of National Security,” in The Oxford Handbook of International Security, ed. Alexandra Gheciu and William C. Wohlforth (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), 259–73.