35 Disciplinary Neoliberalism, the Tyranny of Debt and the 1%

Introduction

At least since the Global Financial Crisis (2007/08) and the Occupy Movement, if not before, more and more people are waking up to the fact that global income and wealth inequality have been worsening both between and within nations. Indeed, the financial services holding company Credit Suisse reported that ‘the top percentile now own half of all household assets in the world’ (2015: 19). If we consider the top decile, the top 10% of wealth holders now own 87.7% of all outstanding global wealth (2015: 24). In the political economy literature, there is a recognition that this period of increasing inequality has coincided with what Stephen Gill (1995) has called ‘disciplinary neoliberalism'. For Gill, ‘disciplinary neoliberalism’ encompasses forms of macro and micro structural and behavioral power that reconfigures both the state and society to serve the interests of capital. These reconfigurations of state and society and their political economies are often locked-in by what he calls ‘new constitutionalist’ measures (Gill and Cutler, 2014). Such measures include trade agreements like the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the regulatory framework of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), and the Maastricht Treaty, just to name some of the most prominent examples. For Gill and others concerned with the turn to disciplinary neoliberalism, the policies that lead to new forms of structural and behavioral power are largely the result of the stagflationary crises of the 1970s in advanced capitalist countries, as well as the general debt crisis across the developing world in the 1980s. Thus, in fits and starts over the last 30 years or so, states and societies have been reconfigured in the interests of global businesses and the accumulation of capital.

In this chapter, I want to show how neoliberal policies have contributed to increasing inequality, the tyranny of debt and rise of the 1%. I will argue that this trend is largely the result of a debt-based monetary system and that, without substantial change, we will likely see an intensification of neoliberal policies, greater inequality and more austerity – particularly for the most vulnerable among us.1 To substantiate my argument, I will first discuss our current monetary order and why this leads to expanding national, business and personal debt across virtually every society, and particularly those with the largest economies by GDP. In the second section, I will explore what I call the debt–neoliberalism–austerity nexus by focusing on three key neoliberal policies: fiscal discipline, privatization and trade liberalization. In the third section, I show how these policies (among other factors) have contributed to the rise of the 1% and greater global inequality in income, wealth and life chances by examining the example of Wal-Mart and the Walton family in the United States.

Money and the Creation of National Debts

I want to argue that it is very difficult to have a clear understanding of the turn to ‘disciplinary neoliberalism’ without first having a clear understanding of how new money gets produced in our economies and the debt that results. But before I discuss this process and the consequences for our societies, we should give pause and consider the very basic, but too often neglected question: what is money? While there is considerable debate on the issue, there are two primary schools of thought. The first school sees money as metallic coins, particularly of the gold and silver variety. These ‘metalist’ scholars argue that gold and silver have an intrinsic value and, therefore, are the only true sources of money (Ingham, 2004: 7). Up until 1971, when President Richard Nixon ended the convertibility of US dollars to gold, there is little doubt that most people believed real money was mostly gold. The question is whether they are correct to see gold as the only true forms of money, which brings us to the second school of thought on money that challenges the metalist thesis. These scholars argue that money should never be confused with a medium of exchange (that is, the stuff that represents money). They point to the fact that over human history, all sorts of material goods – cigarettes, cowrie shells, vodka, cows, wampum, cacao, silver, gold, paper bills, etc., have represented money (Davies, 2002: 27). Since all manner of mediums have been used as money, critical scholars think of money as an abstract claim on society and nature expressed in a unit of account (e.g., dollars, euros, pounds). In other words, since money is in reality an abstract concept, it can be represented by virtually anything – though some material things are certainly more practical than others. Today, we are used to thinking of money as the notes and coins we use in day-to-day life. However, in most developed countries, notes and coins only represent a tiny fraction of the money supply. For example, in the United Kingdom, only 3% of the money supply takes the form of notes and coins, while it is a bit higher in the United States at 11%. The rest of the money is simply numbers in computers on the double-entry balance sheets of commercial, central and investment banks. Those of us who use Internet banking to receive deposits and pay our bills will not be too surprised to find this out.

Despite the evidence to the contrary, that money is indeed an abstract claim on society and nature measured in a unit of account, there will still be those who think that gold (and sometimes silver) is the only ‘true’ money. These metalists argue for a return to the gold standard but, as Eichengreen (2011) points out, any return to the gold standard not only has practical issues to be worked out, but would, more importantly, be a disaster for the global economy. No one knows exactly why certain humans had a fascination with gold, but it was particularly Eurasians who coveted the metal because they thought of it as the currency of power (Bernstein, 2004; Kemmerer, 1944). So while we can conceive of money as primarily an abstract claim on society and nature expressed in a unit of account, for a considerable amount of time, gold and silver were its chief representatives. The problem with a reliance on gold and silver as the only true money is that, for an economy to expand, more gold and silver would have to be found. But as we know, both metals are in limited supply, sparking geopolitical competition among European powers during the era of exploration, transatlantic slavery and colonization. So how could the money supply expand without having to constantly find gold and silver? It turns out that this problem confronted intellectuals in England in the seventeenth century.

As Wennerlind argues, intellectuals were consumed by the problem of how to expand the money supply (2011: 17). At first it was thought that base metals like lead could be transformed into gold and silver – the proverbial Philosopher's Stone. When this idea was proven incorrect, an epistemological breakthrough was made whereby members of the Hartlib Circle – an early scientific correspondence society – thought of money as an abstract unit of account. If money could be represented by anything – not just gold and silver – then it was possible to create more of it. Important as this breakthrough was, in practice goldsmiths had already been expanding the money supply by circulating their own private notes representing coinage deposits over and above what they actually held in their vaults (Davies, 2002: 249ff). For example, a goldsmith might have £500 in gold coins and thinks he can get away with issuing paper notes up to the value of £1,000 (the extra £500 extended through loans at interest). As long as people trust in the fact that they can exchange the notes for gold at some later date, but have no need of cashing in immediately, the notes can circulate as currency, thereby expanding the money supply. However, given the intensity of the debate on the dearth of money, this slight expansion of the money supply as goldsmith credit was not sufficient to ignite a growing economy.

The watershed moment occurred in London when a group of financiers advanced William Paterson's plan for a Bank of England. It is important to recall that up until 1688, when the English Parliament finally subordinated the Crown to its will, any debt taken in the name of the state was the debt of the sovereign, not the people. What London financiers wanted to create was a permanent ‘national’ debt based on the power of Parliament to tax the population. To be sure, this was a period of intense geopolitical competition in Europe and the Bank was ostensibly chartered to finance a war with France. In return for £1,200,000, the Crown-in-Parliament promised an 8% return to the Bank's investors plus a yearly management fee of £4,000 (Davies, 2002: 260; Wennerlind, 2011: 108ff). The £1,200,000 extended to the Crown-in-Parliament was not all given in coinage, but mostly in paper notes believed to be backed by silver coinage. The inventor of the Bank believed that only a minor percentage of silver coin (15–25%) was needed to ensure the confidence in the use and circulation of the notes (Wennerlind, 2011: 110). These notes, according to Wennerlind, became ‘England's and Europe's first widely circulating credit currency’ (2011: 109, my emphasis). Thus, the money supply was expanded significantly with the birth of the first permanent ‘national’ debt – a debt rooted in war and backed by taxation. As yet, there is no global history on the creation of ‘national’ debts worldwide, but several factors influenced the globalization of the institution: (1) colonialism and the power of international finance; (2) geopolitical competition and the need to emulate the success of the Bank of England and the perceived gold standard; and (3) the willingness to borrow from international creditors.

Whatever the precise history of national debts, we can be sure that permanent national debts have been created worldwide, backed by a state's power to collect a revenue stream, since the watershed moment of the Bank of England's creation (Gnos and Rochon, 2002). This basic relationship is at the heart of all modern indebted states and virtually every state on the planet has a ballooning national debt. So, to be clear, if public officials want to borrow more money than they receive in taxes, fees and fines, they are structurally forced to go into debt to private social forces. This is called ‘the capitalization of the state’ and means that government bondholders will get a future flow of income from the taxes, fees and fines collected by the state (Nitzan and Bichler, 2002; 2009). State revenue is also collected when states privatize public assets and sell licenses to the public. Those who buy state debt can also sell their ownership claims to another investor in a secondary market, which increases liquidity. In other words, as Marx (1981: 429) claimed: ‘the initiators of the modern credit system take as their point of departure not an anathema against interest-bearing capital in general, but on the contrary, its explicit recognition'.

This is a crucial point to consider for three reasons. First, most people have little idea how new money enters the economy. Second, most people who have reflected upon the creation of money think that banks only intermediate between savers and borrowers. The idea here is simple: banks take in deposits and, since not everyone will be withdrawing their money all the time, banks simply use a portion of these deposits they do not have to hold as ‘reserves’ to create loans for willing borrowers. This interpretation is completely incorrect as the Bank of England has stated and as Richard Werner's research has empirically demonstrated (Di Muzio and Robbins, 2016; McLeay et al., 2014; Turner, 2015; Werner, 2014a, 2014b). This brings us to our third point and how new money is actually created in most modern societies. Banks do not take from depositors to issue loans; rather, when they make a loan to a client, they create the money by digitally inputting a deposit into the customer's account. This means that privately-owned banks create the majority of the money supply as debt in advanced capitalist economies. Most governments do issue notes and coins and make a small profit from doing so, but by far the most dominant form of money is electronic, not notes and coins. The heterodox school of thought known as Modern Money Theory does recognize that the majority of the money supply is created by commercial banks when they make loans. However, Modern Money Theory is largely descriptive in nature and the school has done precious little to suggest any major reforms to the way money is produced in capitalist economies (Huber, 2014).

So, when we start to think about neoliberal policies, we need to have this understanding of money in the front of our minds and understand that there is nothing technically stopping our democratic governments from issuing an interest-free currency and spending it on productive projects and programs benefitting society. Doing so would not accumulate a national debt. Of course, there are debates about how this can be done (and done responsibly), but the fact that these debates are only marginal at the moment is one reason to fear that neoliberal policies will intensify over time. This is largely because the main justification for neoliberal policies, as I will argue, is public and corporate debt (Di Muzio and Robbins, 2016; Hager, 2013, 2016; Soederberg, 2012, 2013a, 2013b, 2014). This fiscal-financial system works particularly well for the 1% who own considerable shares in the national debts of the world. According to the Economist debt clock, total government debt worldwide is just under US$60 trillion and counting.2 Ownership over the capacity to create money is one of the chief ways that money gets redistributed from the public to a minority of private hands (Creutz, 2010; Hager, 2016). This does not have to happen for any scientific or natural reason, but is merely a legacy of historical social struggles between a monarch and moneyed and propertied men. I would like to argue that this system of money/credit creation needs to be overcome if we are to set policies that move away from neoliberal austerity.

The Debt–Neoliberalism–Austerity Nexus

To recall, the main task of this chapter is to demonstrate how neoliberalism has strengthened inequality, contributed to the rise and rise of the 1% and that this transformation is rooted in a debt-based money system owned and controlled by private social forces. As you are likely aware from reading this Handbook, the term ‘neoliberalism’ is a contested concept that is interpreted in many ways by different scholars (Cahill, 2014; Harvey, 2005; Saad-Filho and Johnston, 2005). Neoliberalism, I contend, is best understood as a set of policy prescriptions that are associated with what Williamson (1990) termed ‘the Washington Consensus'. The term is called the Washington Consensus because these policy prescriptions were generally agreed upon by the International Monetary Fund, World Bank Group and the US Treasury – all located in Washington, DC. Williamson arrived at these policies because he argued that they were the most prescribed in structural adjustment programs imposed upon debtor nations of the Global South beginning in the 1980s. Thus, it is very important to understand how the debt crisis of the Global South contributed to neoliberal policy prescriptions that eventually came to be applied in the Global North.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, US and UK banks, often working as consortiums, lent large sums of money to virtually every developing nation and some of their largest corporations. These loans were issued at variable interest rates and were appealing at the time because interest rates were considerably low and sometimes negative (George, 1988). However, largely due to a historically unprecedented increase in the oil price (which effects virtually all prices, albeit differentially), developing nations now had to pay higher prices for oil – a commodity denominated in US dollars. This rapid hike in the oil price by 407% from 1970 to 1974 was orchestrated by officials in the US government, so that oil producers would help fund growing US budget and trade deficits and purchase American arms (for an overview of the literature, see Di Muzio, 2015b: 122ff). This made servicing the interest on the debt more difficult, particularly for poorer nations with fewer resources to monetize on global markets and earn US dollars to service their debt. If this was not enough, Paul Volcker, then-chairman of the Federal Reserve in the United States, raised the Federal Funds Rate by a magnitude of 300% from a lower rate of 4% in 1973 to 16% by 1980–81. Thus, within the span of a few years, the debts of the developing world ballooned by unprecedented levels. Total developing world debt went from US$19 billion in 1960 to US$376 billion by 1979 – an increase of 1,879% (Di Muzio and Robbins, 2016, citing Stavrianos, 1981: 127).

The official excuse for this massive increase in interest rates was to dampen inflation in the economy of the United States. However, as I have suggested elsewhere, a close look at the data does not bear this out (Di Muzio, 2015: 122ff). The most likely hypothesis is that interest rates were intentionally raised in order to burden the developing world with a permanent debt to be serviced in perpetuity. And, indeed, the total debt of the developing world is now US$4 trillion and counting. If this sounds a bit strange, consider the fact that trapping people/nations in debt has long been a strategy of the powerful (see Di Muzio and Robbins, 2016; Hudson, 2015; Perkins, 2004; Soederberg, 2014). There are many examples, but I will only mention two here. First, President of the United States and slave-owner Thomas Jefferson's native strategy – that is, a strategy to get more land – was to entrap the Amerindians with debt and, when they could not repay, expropriate their land. Authorities in the British Empire also used the same strategy around the world by extending loans to governments. In 1903, the senior diplomat, Arthur Hardinge, wrote the following to the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Henry Charles Keith Petty-Fitzmaurice, fifth Marquess of Lansdowne, regarding Persia (modern-day Iran): ‘The more we get her into our debt, the greater will be our hold and our political influence over her government’ (cited in McLean, 1976: 297). But it was the liberal writer on imperialism, John A. Hobson, who noticed that the strategy applied far more broadly:

The creation of public debts is a normal and a most imposing feature of Imperialism. … It is a direct object of imperialist finance to create further debts, just as it is an object of the private money-lender to goad his clients into pecuniary difficulties in order that they may have recourse to him. Analysis of foreign investments shows that public or State-guaranteed debts are largely held by investors and financiers of other nations; and recent history shows, in the cases of Egypt, Turkey, China, the hand of the bond-holder, and of the potential bond-holder, in politics. This method of finance is not only profitable in the case of foreign nations, where it is a chief instrument or pretext for encroachment. It is of service to the financial classes to have a large national debt of their own. The floating of and the dealing in such public loans are a profitable business, and are means of exercising important political influences at critical junctures. (Hobson, 1902: Chapter 7, my emphasis)

In short, as Richard Robbins and I have argued, debt is a technology of the powerful in their quest to accumulate more monetary units differentially (relative to others) over time. With this in the background, we can now summarize the ten policy prescriptions of the Washington Consensus that were developed in the 1980s as structural adjustment programs imposed upon 129 indebted states that had difficulty servicing payments to their creditors:

The Washington Consensus

- Fiscal discipline (avoid large deficits that lead to mounting national debt);

- Invest in primary health care, education and infrastructure to encourage economic growth;

- Broaden the tax base and apply moderate marginal tax rates;

- Interest rates should be positive and market determined;

- Exchange rate should be competitive internationally;

- Liberalization of trade (lower tariffs);

- Liberalization of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI);

- Privatize state assets;

- Deregulate the economy to encourage competition/growth;

- Ensure property rights are secure.

Ostensibly, these policies were encouraged to promote economic growth in countries with large external debts. ‘External debt’ is a term indicating that these countries owed their debts in foreign currencies – particularly US dollars and British pounds. To earn these currencies, production must be geared towards earning foreign exchange by selling goods or services on the international market. And since the debt is perpetual, this means the discipline of neoliberal policies will also be perpetual, if not intensifying over time. To consider this idea, let's take a closer look at three of the leading policies imposed by the international financial institutions and US Treasury.

Fiscal discipline is a key policy goal promoted by the international financial institutions and the US Treasury. The idea here is fairly basic: governments should not spend beyond what they collect in revenue. In other words, deficits should be avoided, since yearly deficits lead to mounting national debt and, ultimately, higher interest payments to creditors. The problem with this idea, and why even the largest capitalist country on earth – the United States of America – run consistent deficits, has to do with the reality of the fiscal system (how a state raises revenue and spends). First, we have to keep in mind that the deficit is an ‘ex post value', which means it is only calculated at the end of the fiscal year – whatever the date may be in each individual state (Parguez and Seccareccia, in Smithin, 2000: 112). Only then do we know whether we have a surplus (the state has taken in more revenue than it has spent) or a deficit (the state has spent more money than it has taken in).3 Governments can try to budget based on a previous year's revenue and typically do engage in revenue forecasts but, ultimately, deficits are far more common than surpluses. Still, telling governments that they should aim for balanced budgets (no deficits) is akin to taking away the power of the state to spend into the economy during times of economic recession or depression.

It also, and perhaps more importantly, effectively delegitimizes the idea that democratic governments should be able to create their own new money to meet the priorities set forth in their mandate. But in the current system, as we have noted above, if a state does spend more than it gathers in revenue, it is structurally forced to go into debt to a minority of private social forces. Once again, we are operating as if this has to happen by some natural law. The people who most benefit from this type of a fiscal system are creditors to the state – those who have capitalized state debt and effectively privatize a portion of the state's domestic revenue and redirect it towards themselves. Put simply, the very concept of fiscal discipline completely occludes the idea that the state has the sovereignty to create money at will, interest free. Let's consider a brief example. Suppose Finland wants to build a new public hospital in a region with a growing population but few health services. If we do not follow the neoliberal strait-jacket of fiscal discipline, the government of Finland can simply tender a call for bids to private construction companies. Once the government decides who will build the hospital, it can order the Bank of Finland to create the money interest free rather than borrow the money from the private sector.4 Theoretically, all the Bank of Finland needs do is credit the government's current account by entering numbers into a computer. But if we stay within present fiscal thinking, suppose the new hospital can only be financed by deficit spending. In this scenario, the Finish government will borrow – say 1,000,000 euros – to build the hospital. Now suppose that it will take at least two years for the government to pay off this debt at a compound interest rate of 5%. What this means is that the cost of the hospital will actually be 1,102,647.38. The interest charged (102,647.38), makes the hospital far more expensive for taxpayers and goes to private social forces who lent the government their money or, alternatively, a bank that created the credit-money out of thin air (Collins et al., 2014; Werner, 2014a, 2014b). Cleary, the first option – from a cost-to-taxpayers’ point of view – is better than the second option. This was noticed by none other than the classical economist David Ricardo in addressing England's national debt:

It is evident therefore that if the Government itself were to be the sole issuer of paper money instead of borrowing it of the bank, the only difference would be with respect to interest: the Bank would no longer receive interest and the government would no longer pay it. … It is said that Government could not with safety be entrusted with the power of issuing paper money – that it would most certainly abuse it. … I propose to place this trust in the hands of three Commissioners. (cited in Zarlenga, 2002: 297)

But we are told by neoliberals and others that states must balance the budget and, if they cannot manage this task, must go into debt to private social forces. This then leads to the tyranny of perpetual debt and a justification for more austerity programs that typically harm the most vulnerable people in any given society (Abouharb and Cingranelli, 2007).

A second leading policy of the Washington Consensus is the privatization of state-owned assets. Historically, states have generally decided to nationalize assets that are deemed to be of benefit to the public at large, running them at-cost. Examples include water sanitation systems, waste and sewage systems, public education, the provision of electricity, and so on. These utilities, where they do not take on debt, can be run at-cost and, therefore, are far less expensive to run than if they were run by private companies for profit. However, within the context of a ‘debt crisis’ or what some have called the ‘fiscal crisis of the state’ in the Global North, selling state assets is one of the most common ways for governments to raise additional revenue to pay off rich creditors. In the two decades that followed these crises, a rash wave of privatizations occurred:

Over the past two decades [1980–2000], privatization has become a key ingredient in economic reform in many countries. In the last decade alone, close to one trillion US dollars worth of state-owned enterprises have been transferred to the private sector in the world as a whole. The bulk of privatization proceeds have come from the sale of assets in the OECD member countries. Privatizations have affected a range of sectors such as manufacturing, banking, defence, energy, transportation and public utilities. The privatization drive in the 1990s was fueled by the need to reduce budgetary deficits, attract investment, improve corporate efficiency and liberalizing markets in sectors such as energy and telecommunications. The second half of the 1990s brought an acceleration of privatization activity especially among the members of the European Monetary Union (EMU), as they started to meet the requirements of the convergence criteria of the Maastricht Treaty. (OECD, 2001: 43)

What this passage suggests is that a central reason for the mass wave of privatizations since 1980 has been ‘budgetary deficits'. This trend has continued into the twenty-first century with just under US$500 billion in privatizations across the OECD up until 2009, and another US$1.1 trillion dollars in privatization from 2009 to 2013 (OECD, 2009; see also KPMG, 2013). The impacts of global privatizations are fiercely debated and the literature is too vast to consider here, but many critical scholars contend that privatizations lead to higher administered prices that block people from services, unaccountable corporate control over key community resources and an additional revenue stream for the 1% (Hagen and Halvorsen, 2009). In a short chapter such as this, we cannot consider all of the evidence on the impacts of privatization, but it is perhaps worth briefly discussing the privatization of fresh water services given the ubiquity of its application in the Global South.

The IMF and the World Bank have been active in supporting the transition from publically-managed to corporate-dominated social services such as water. Both international financial institutions have included water privatizations as loan conditionalities – conditions that inquiries into IMF loans have revealed are generally applied on the ‘smallest, poorest and most debt-ridden’ African countries (Grusky, 2001; see also Roberts, 2008). The results of the neoliberal reforms pressed by the international financial institutions have been predictably disastrous. Infrastructure has not expanded to bring poor populations into the grid of piped water and dramatic price increases have forced the poor to radically cut down on their use of water and fetch water from dubious sources, significantly increasing health risks. In addition to the widespread corruption and bribery that has accompanied privatizations, the reforms are being implemented undemocratically with loan documents often remaining secret and in violation of existing laws. Such is the case in South Africa where, despite the fact that it is the only country that constitutionally protects the people's right to water, over 10 million residents have had their water cut off since the implementation of a ‘cost recovery’ program inspired by the World Bank (Barlow and Clarke, 2002; Chirwa, 2004). In fact, water privatizations appear to be such a disaster worldwide that the Transnational Institute has counted 180 re-municipalizations of water across 35 different countries in the last 15 years (Kishimoto et al., 2014). This is a hopeful trend, but the future of water privatization is still being written as companies vie to get their hands on one of the world's most-needed resources.

The third Washington Consensus policy is also related to debt: trade liberalization. Trade liberalization is essentially the reduction of tariff barriers and removal of non-tariff barriers (e.g., quotas, licensing rules) or their commutation into prices so that goods and services can be more easily traded between nations. Greater tariff liberalization facilitates goods crossing borders, therefore making the exploitation of cheap labor easier for corporations as they seek to accumulate differential earnings. Nations have typically used tariff barriers to shield national industry from international competition because, all things being equal, tariffs on foreign made products increase the price of those products and encourage consumers to choose local or nationally produced goods. However, after World War II, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade was set up to harmonize tariffs downward. The agreement was eventually institutionalized as the World Trade Organization in 1995, an intergovernmental institution that helps regulate trade and encourages trade negotiations among nations. Moreover, a range of bilateral and multilateral trade agreements have been signed like the NAFTA, GATS and Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs). These agreements have been largely pushed by giant corporations in their quest for differential earnings and have been widely unpopular with domestic populations, as demonstrated by recurrent protests since the World Trade Organization protest in Seattle, Washington in 1999.

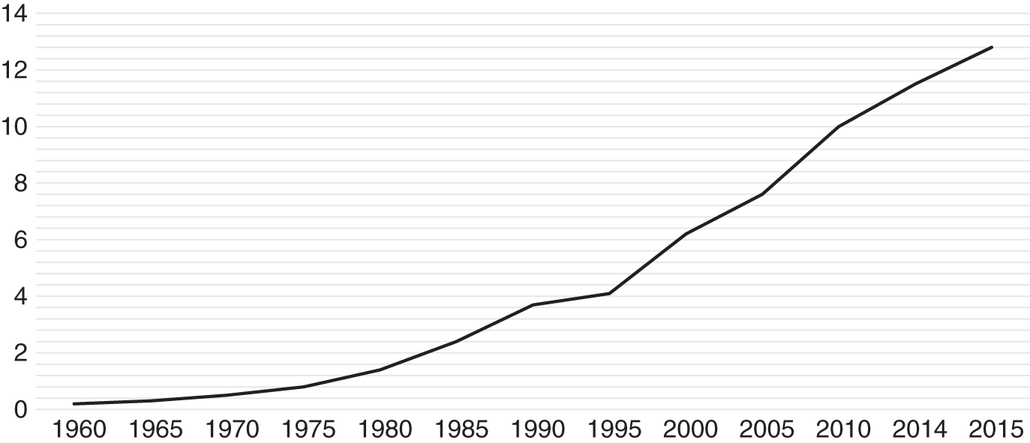

There are a range of reasons that motivate corporate leaders to lobby for trade agreements and greater liberalization of trade, but here we will focus on production costs. Many believe that large corporations finance their operations and/or expansion out of retained earnings. But the evidence seems to suggest otherwise. For example, take the level of non-financial business debt in the United States in Figure 35.1.

Figure 35.1 US non-financial business debt, 1960–2014 Q1 (trillion US$)

Source: Federal Reserve, LA144104005.Q.

It not only appears from this chart that business debt is increasing over time, but also that there was an acceleration in the accumulation of corporate debt from 1995 – the era typically associated with greater globalization of the world economy. To put this level of debt in perspective, consider that the national debt of the United States is about US$16 trillion at the time of writing, whereas in the fourth quarter of 2015 total business debt stood at US$12.8 trillion. The entire debt of the non-financial corporate universe in the United States is almost as large as its entire national debt. This is important to consider because interest is a cost to business and these costs eventually must be pushed on to consumers. As Rowbotham (1998) pointed out some time ago, business cannot control the cost of interest they have to service, but what they can control in non-unionized environments is the price they pay for labor. This appears to be the primary reason why corporations closed down factories across the Global North and moved production to countries such as China and Mexico, among other nations with lower GDP per capita and a plentiful workforce willing or compelled to work for very low wages. Neoliberals celebrate the decline of manufacturing in advanced capitalist economies because they interpret the phenomenon as giving rise to a services economy which, they argue, can also provide for stable and well-paying jobs in the Global North (Rowthorn and Ramaswamy, 1997). However, many argue that the deindustrialization and decline of manufacturing in advanced capitalist economies led to the decline of unions, decent-paying jobs and job security. While many cities fell victim to deindustrialization, this trend was perhaps best captured in Michael Moore's film Roger & Me. The film explores what happened to Flint, Michigan, USA after General Motors CEO, Roger Smith, decided to terminate 30,000 workers in the 1980s. The jobs were relocated to Mexico, where cheaper labor could be employed in the production process. With lower tariffs, General Motors could then re-import its products from Mexico and sell them to Americans. After the layoffs, Flint is shown to be left utterly demoralized, with an epidemic of business closures, high unemployment and people being evicted from their homes because they fail to pay rent or service their mortgages. Thus, trade and investment liberalization, pushed for by large corporations, has had a tendency to decimate traditional manufacturing employment in the Global North and is one of the reasons suggested – particularly in the United States – for the disappearance of the middle class (for the case of Canada, see Brennan in Di Muzio, 2014: 59–81).

American Winter, Wal-Mart and the 1%5

There are a number of ways to demonstrate how ‘disciplinary neoliberalism’ and debt have contributed to the wealth of the 1% and growing inequality. However, an especially pertinent example has become evident in recent years through Senator Bernie Sanders’ consistent berating of America's richest family, the Waltons of Wal-Mart fame, for effectively taking public subsidies. Because the wages Wal-Mart pays to its employees are so low, many of Wal-Mart's workers are forced to go on food stamps, seek public subsidies and Medicaid, which are paid programs financed by tax revenue. For example, one study reported that Medicaid expenditures by the government increased by US$898 per Wal-Mart worker in the United States (Hicks, 2015). This represents a yearly taxpayer subsidy of US$1.3 billion dollars to the company and its shareholders. Yet another study done by Americans for Tax Fairness estimated that the total subsidy received by Wal-Mart, when food stamps and public housing are included along with Medicare, is closer to US$6.2 billion.6 So how low are Wal-Mart's wages? It turns out, for a family of four, below the official poverty rate:

Walmart's average sale Associate makes $8.81 per hour, according to IBISWorld, an independent market research group. This translates to annual pay of $15,576, based upon Walmart's full-time status of 34 hours per week. This is significantly below the 2010 Federal Poverty Level of $22,050 for a family of four.7

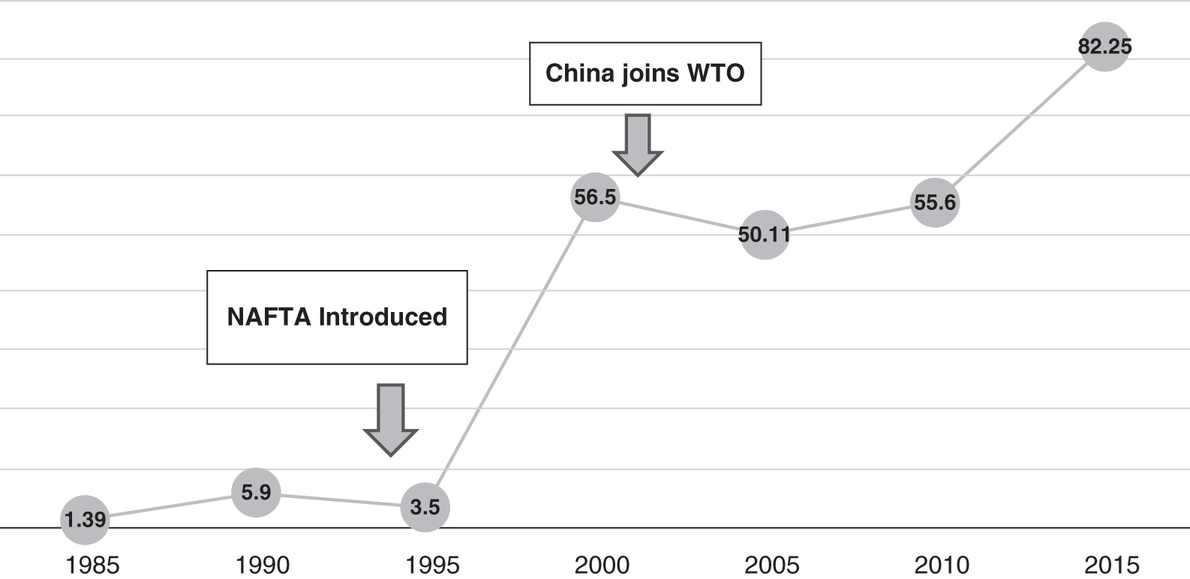

If Wal-Mart workers shared in that 430% increase in the company's value (see below), the average yearly salary would be (rounding up) US$66,000 a year, well above the official poverty line.8 What this suggests is that the wealth of the Waltons, in part, is being subsidized by American taxpayers due to the insufficient wages it pays its workers. In the last fiscal year (2015), Forbes reported that the Walton family was worth US$149 billion, or more than the total wealth of the bottom 42% of the American population combined.9 Their wealth is primarily held in Wal-Mart shares and this leads us to ask the following three questions: (1) what happened to the share price of the company after the introduction of NAFTA, which facilitated trade with Mexico?; (2) what happened to the share price of the company after China joined the WTO in December 2001?; and (3) was the exploitation of cheap wage-labor in the United States complemented by the exploitation of super-cheap labor abroad?

Figure 35.2 Wal-Mart share price in US dollars (billion) at five-year intervalsSource: Yahoo Finance.

There are, of course, a range of factors that bear on Wal-Mart's earnings and, therefore, the overall market capitalization of the firm. But the hypothesis advanced here is that the ability of Wal-Mart's suppliers to exploit cheaper labor in both Mexico and China – in part, facilitated by so-called free trade agreements – was a major contributor to the increased valuation of the company, as demonstrated in Figure 35.2. From January 1994 to May 2016 (the time of this writing), the value of the company went from just over US$40 billion to just over US$212 billion. This represents an increase of 430% over the period.10 To be sure, this is also a period of Wal-Mart's expansion both in the United States and abroad, and there is little doubt that this also contributed to increased earnings and therefore the private fortune of the Walton family. But there can be very little doubt that the liberalization of trade helped propel the Waltons to a level of wealth not seen before these agreements, since they allowed their suppliers to escape high-wage countries for lower-wage ones, thereby reducing costs.

However, exploiting cheaper wage-laborers to reduce costs and boost earnings is not the only reason why Wal-Mart puts pressure on its suppliers to cut costs. The company is also in debt to the tune of US$50 billion and must pay its creditors varying rates of interest from 2.5% at the low end to 6.5% at the high end.11 If we take a simple interest rate average of 4.5%, Wal-Mart would owe its creditors US$225 million in interest over the period of a year. This can continue so long as its quarterly earnings remain in the billions of dollars, but it is important to note that interest is a cost to Wal-Mart and, therefore, incentivizes the company to cut costs and demand cost-cutting from its suppliers. So, both from the perspective of equity, which capitalizes the potential of the firm to generate earnings, and debt, which capitalizes the assets of the firm, Wal-Mart and its suppliers are motivated to find the cheapest pools of competent and compliant wage-labor. Thus far, as evidenced by the rapid rise of the Walton family into the stratosphere of the 1% after the passing of NAFTA and China's entry into the WTO, the strategy appears to be working. How long this will continue is anyone's guess, but there are movements in the United States pushing for a higher minimum wage and Bernie Sanders continues to make noise about a rigged economy that favors the 1% at the expense of a disappearing middle class.

Conclusion

In this chapter, I have argued that neoliberal policies – what Stephen Gill calls ‘disciplinary neoliberalism’ – are largely the result of how we produce new money as debt. We surveyed how international loans were made to the developing world from the 1960s under variable interest rates. Thanks to rigged oil prices and the subsequent Volcker shocks, the United States ensnared the developing world in perpetual debt service to Northern banks. The consequence of this was an explosion of well-documented neoliberal policies across the Global South. I have also tried to show how neoliberal policies, now inflicted with increasing frequency on the Global North, contributes to stark inequality, the tyranny of perpetual debt and the rise of the 1%. To do so, I discussed three key policies of the Washington Consensus, applied in both Global North and South. Last, though more empirical work could be done on the rapid rise of Wal-Mart's share price, I demonstrated that there is considerable evidence to suggest that the signing of NAFTA and China's entry into the WTO boosted Wal-Mart's share price and, thus, the capitalized fortunes of the Walton family by 430%. Austerity politics and the intensification of neoliberalism will likely continue so long as governments are structurally forced into debt when they want or need to spend more than they collect in taxes fines and fees. Moreover, as non-financial corporations take on more debt, they are incentivized to find cheaper pools of labor, since labor cost is far more controllable than the interest rate. Moving towards a form of democratically controlled sovereign money would remove the power of the social forces of finance to discipline governments, while simultaneously eliminating the excuse for neoliberal austerity – ever more mounting debt across all levels of society.

Notes

1. This assessment also appears to be shared by Hudson (2015).

2. Economist debt clock, www.economist.com/comment/1325345 (accessed 15/9/2016).

3. Though this is true for the fiscal year, governments would have some clue of their position from month-end data.

4. It should be noted that, since Finland decided to join the Euro, this is illegal under the current system.

5. American Winter (2013) is a film by Harry and Joe Gantz that follows families struggling in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. Rich Hill (2014), by directors Andrew Droz Palermo and Tracy Droz Tragos, is another great film on the lives of three American boys and their struggles with family and poverty in the USA.

6. www.forbes.com/sites/clareoconnor/2014/04/15/report-walmart-workers-cost-taxpayers-6-2-billion-in-public-assistance/#484c00527cd8 (accessed 4/5/2016).

7. http://makingchangeatwalmart.org/factsheet/walmart-watch-fact-sheets/fact-sheet-wages/ (accessed 3/5/2016).

8. http://makingchangeatwalmart.org/factsheet/walmart-watch-fact-sheets/fact-sheet-wages/ (accessed 4/5/2016).

9. www.forbes.com/profile/walton-1/ (accessed 3/5/2016).

10. The value of the company for 1994 is calculated by multiplying 3.14 billion outstanding shares by US$12.93 in January 1994. The value for May 3, 2016 is taken from https://au.finance.yahoo.com/echarts?s=WMT#symbol=WMT;range=my (accessed 3/5/2016).

11. http://quicktake.morningstar.com/stocknet/bonds.aspx?symbol=wmt (accessed 4/5/2016).

References

and (2007) Structural Adjustment and Human Rights. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

and (2002) ‘Who Owns Water?' The Nation, 275 I. 7: 11–14.

(2004) Gold: The History of an Obsession. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

(2014) The End of Laissez-Faire: On the Durability of Embedded Neoliberalism. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

(2004) ‘Water Privatization and Socio-Economic Rights in South-Africa.' Law, Democracy and Development, 2: 181–206.

, , and (2014) Where Does Money Come From? A Guide to the UK Monetary and Banking System. London: New Economics Foundation.

Credit Suisse (2015) Global Wealth Report. October.

(2010) The Money Syndrome: Towards a Market Economy Free from Crisis. Peterborough: FastPrint Publishing.

(2002) A History of Money: From Ancient Times to the Present Day. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. https://www.credit-suisse.com/corporate/en/research/research-institute/global-wealth-report.html (accessed 7/2/2018).

Di Muzio, Tim (ed.) (2014) The Capitalist Mode of Power: Critical Engagements with the Power Theory of Value. London: Routledge.

(2015) Carbon Capitalism: Energy, Social Reproduction and World Order. London: Rowman Littlefield.

and (2016) An Anthropology of Money. New York: Routledge.

and (2016) Debt as Power. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

(2011) ‘A Critique of Pure Gold.' The National Interest, September/October: 35–45.

(1988) A Fate Worse than Debt. London: Penguin.

(1995) ‘Globalization, Market Civilization and Disciplinary Neoliberalism.' Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 24(3): 399–423.

and (2014) New Constitutionalism and World Order. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

and (2002) ‘Money Creation and the State.' International Journal of Political Economy, 32(3): 41–57.

(2001) ‘Privatization Tidal Wave: IMF/World Bank Water Policies and the Price Paid by the Poor.' Multinational Monitor, 22(9): 14–19.

Hagen, Ingrid J. and Thea S. Halvorsen (eds) (2009) Global Privatizations and Its Impact. New York: Nova Science Publishers.

(2013) ‘What Happened to the Bondholding Class? Public Debt, Power and the Top One Per Cent.' New Political Economy, 19(2): 155–182.

(2016) Public Debt, Inequality, and Power: The Making of a Modern Debt State. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

(2005) A Brief History of Neoliberalism. London: Oxford University Press.

(2015) ‘Does Wal-Mart Cause an Increase in Anti-Poverty Expenditures?' Social Science Quarterly, 96(4): 1136–1152.

(1902) Imperialism: A Study. New York: Cosimo.

(2014) ‘Modern Money Theory and New Currency Theory: A Comparative Discussion, Including an Assessment of Their Relevance to Monetary Reform.' Real-World Economics Review, 66: 38–57.

(2015) Killing the Host: How Financial Parasites and Debt Bondage Destroy the Global Economy. Petrolia, CA: Counterpunch Books.

(2004) The Nature of Money. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

(1944) Gold and the Gold Standard: The Story of Gold Money, Past, Present and Future. New York: McGraw-Hill.

, and (2014) Here to Stay: Water Remunicipalisation as a Global Trend. Amsterdam: Transnational Institute. www.tni.org/en/publication/here-to-stay-water-remunicipalisation-as-a-global-trend (accessed 4/30/2016).

KPMG (2013) The Privatization Barometer Report. www.kpmg.com/IT/it/IssuesAndInsights/ArticlesPublications/Documents/PB-AR2013.pdf (accessed 4/30/2016).

(1981) Capital. Volume 3: A Critique of Political Economy. Trans. David Fernbach. New York: Penguin Putnam.

(1976) ‘Finance and the “Informal Empire” before the First World War.' Economic History Review, 29(2): 291–305.

, and (2014) ‘Money Creation in the Modern Economy.' Quarterly Bulletin Q1. London: Bank of England.

and (2002) The Global Political Economy of Israel. London: Pluto Press.

and (2009) Capital as Power: A Study of Order and Creorder. London: Routledge.

OECD (2001) Financial Market Trends No. 79. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

OECD (2009) ‘Privatization in the 21st Century: Recent Experiences of OECD Countries.' Paris: Corporate Affairs Division, Directorate for Financial and Enterprise Affairs Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (www.oecd.org/daf/corporateaffairs).

(2004) Confessions of an Economic Hit Man. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

(2008) ‘Privatizing Social Reproduction: The Primitive Accumulation of Water in an Era of Neoliberalism.' Antipode, 40(4): 535–560.

(1998) The Grip of Death: A Study of Modern Money, Debt Slavery and Destructive Economics. Charlbury, UK: Jon Carpenter Publishing.

and (1997) ‘Deindustrialization: Its Causes and Implications.’ International Monetary Fund. Economic Issues 10, September. https://www.imf.org/EXTERNAL/PUBS/FT/ISSUES10/INDEX.HTM (accessed 4/30/2016).

and (2005) Neoliberalism: A Critical Reader. London: Pluto Press.

Smithin, John (ed.) (2000) What is Money? London: Routledge.

(2012) ‘The Mexican Debtfare State: Micro-Lending, Dispossession, and the Surplus Population.' Globalizations, 9(4): 561–575.

(2013a) ‘The Politics of Debt and Development in the New Millennium: An Introduction.' Third World Quarterly, 34(4): 535–546.

(2013b) ‘The US Debtfare State and the Credit Card Industry: Forging Spaces of Dispossession.' Antipode: Radical Journal of Geography, 45(2): 493–512.

(2014) Debtfare States and the Poverty Industry: Money, Discipline and the Surplus Population. London: Routledge.

(1981) Global Rift: The Third World Comes of Age. New York: William Morrow and Co.

(2015) Between Debt and the Devil: Money, Credit and Fixing Global Finance. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

(2011) Casualties of Credit: The English Financial Revolution, 1620–1720. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

(2014a) ‘Can Banks Individually Create Money out of Nothing? The Theories and the Empirical Evidence.' International Review of Financial Analysis, 36: 1–19.

(2014b) ‘How do Banks Create Money, and Why Can Other Firms Not Do the Same? An Explanation for the Coexistence of Lending and Deposit-Taking.' International Review of Financial Analysis, 36: 71–77.

(1990) ‘What Washington Means by Policy Reform.' In John Williamson (ed.), Latin American Adjustment: How Much Has Happened? Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics. pp. 5–20.

(2002) Lost Science of Money: The Mythology of Money: The Story of Power. Valatie, NY: American Monetary Institute.