For many travellers, Uzbekistan holds the very heart of the Central Asian Silk Road. Its three main historical centres – Samarkand, Bukhara and Khiva – all resonate deeply with the weight of history, and its bazaars and teahouses still carry echoes, albeit faint at times, of its fabulous past.

Uzbekistan – the “Land of the Uzbeks” – is just the latest name used to describe the ancient lands between the Amu Darya (Oxus) and Syr Darya (Jaxartes) rivers. The Greeks called the region Transoxiana; the Arabs knew it as Mawarannahr, the “Land across the River”. It is here that the last mountain spurs of the Tian Shan and Pamirs yield to the desolate plains and forbidding desert sands of the Karakum and Kyzylkum deserts.

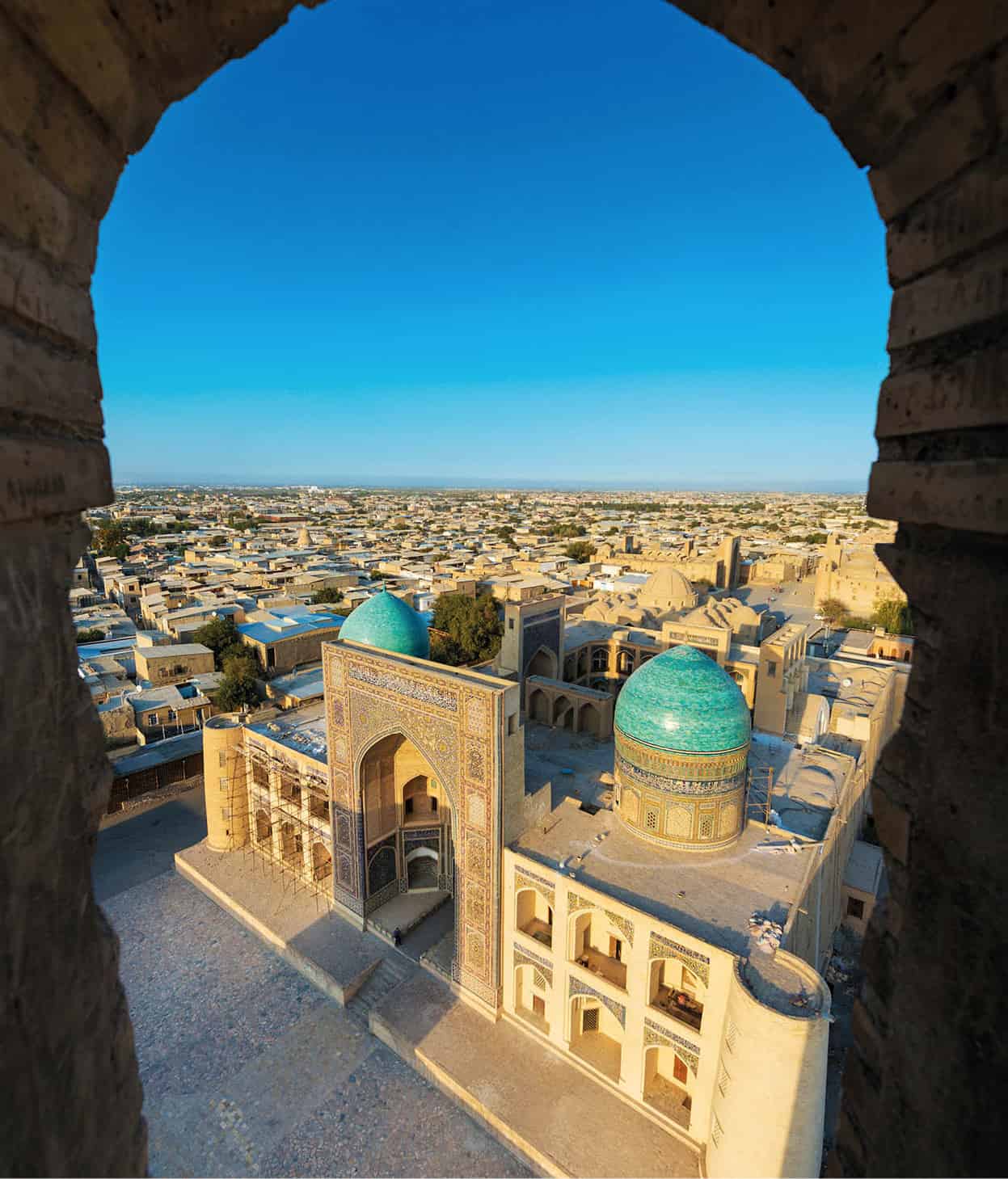

View from the Kalon minaret in Bukhara.

Getty Images

Uzbek women.

Getty Images

Cultural legacy

It is also in essence a cultural meeting point: of Turkic and Persian, nomad and settler, Uzbek and Tajik. This desert land, studded with caravan oases and made rich with plunder and trade, is above all the homeland of Timur (Tamerlane), who has bequeathed modern Uzbekistan with some of the Islamic world’s most fantastic architecture. The Uzbeks themselves are relatively late arrivals, establishing themselves in the 16th century. Most of the madrassas and mosques you see in Uzbekistan date from this era.

The teahouses of Uzbekistan are perhaps the best places in the region to soak up Central Asian culture. Factor in some time to stroll the bustling modern bazaars, sip green tea on a tapchan (tea bed) under the shade of a mulberry tree and dine on shashlyk (mutton kebabs) and freshly baked naan bread. Uzbeks everywhere wear the doppi skullcap with pride, and the fabulously photogenic elders, known respectfully as aksakal or “white beards”, still wear the striped cloaks known as a khalat or chapan. The women of the region are a riot of colour, dressed in shimmering ikat cloth and sporting mouthfuls of gold teeth.

Entering and leaving Uzbekistan

Many visitors arrive first in Tashkent and then fly to Urgench or Nukus before backtracking through the Silk Road cities. (See Travel Tips, click here, for more information on transport in Uzbekistan.)

Places to cross to Kazakhstan are between Tashkent and Shymkent by road (a main crossing and a smaller crossing primarily for lorries) or between Tashkent and Arys or Nukus and Beyneu by rail. The Nukus crossing involves a long and unpredictable rail journey.

There are two road crossings to Kyrgyzstan in the Fergana Valley, one near Andijan, the other near Namangan, although it is necessary to change transport at the frontier. Formalities tend to be more rigorous on the Uzbek side. Daily buses run between Bishkek and Tashkent but require a Kazakhstan transit visa.

A border crossing east of Samarkand leads to Penjikent in Tajikistan, and there is another further south that connects with Dushanbe. A further crossing point at Oybek (daily 24 hours), just south of Tashkent, leads to Khojand in northern Tajikistan, as does a crossing further east in the Fergana Valley just west of Kokand.

Two of the crossings to Turkmenistan (Bukhara to Turkmenabat and Urgench to Dashoguz) involve a long walk or taxi between border posts (both open in daylight). Nukus to Konye-Urgench at Khodjeyli is walkable (9am−6pm).

A border crossing into Afghanistan exists at Termiz but this is not always open to travellers.

Landscapes are not Uzbekistan’s strong point. In fact it has been said that Uzbekistan is two-thirds desert and one-third cotton. Certainly wherever you go in the country you’ll pass the endless fields of “white gold” that make Uzbekistan one of the world’s largest exporters of cotton. Yet in these fluffy white plants lie the roots of an environmental disaster. Decades of Soviet irrigation schemes has lead to chronic water pollution, soil degradation and the almost complete collapse of the Aral Sea Basin (for more information, click here). The damaged environment is just one hangover from the 70 years of Soviet rule, which moved seamlessly to become an independent country under hard-line president Islam Karimov in 1991. After 25 years in charge, he died in September 2016. Defining a new path for independent Uzbekistan remains a huge challenge.

For Silk Road travellers, Uzbekistan is easily the most exciting of the Central Asian republics. It has the region’s most fabulous historical sites, its most outrageous architecture and its most stylish accommodations. Don’t miss it.

After the rigours of the Tian Shan and Pamir mountains, the Fergana Valley must have appeared a paradise to weary travellers and traders. Hemmed in on three sides by the spurs of the Tian Shan, Pamir Alai and Turkestan ranges, the huge and hazy 330-km (200-mile) -long valley is warm, flat and fertile, and its bazaars overflow with fruit and produce.

The valley (known to the Chinese as Dayuan) played a key role in the opening of the Silk Road. Its famed “blood-sweating” horses (believed by the Chinese to be descended from dragons) were in such demand that China forced open the first transcontinental trade routes specifically to gain a supply of the steeds and thus a technical advantage over its marauding nomadic neighbours. The horse trade remained central to the Silk Road long after the secret of silk production had spread to the west.

The valley funnelled Silk Road traffic for centuries, though there’s little evidence of this today. Little remains of the Buddhist temple of Kuva, the 7th- to 11th-century ruins of Kasan and Aksiketh outside Namangan and the Zoroastrian tombs of Pap except some neglected and dusty archaeological remnants.

Merchants with toasted lochira flatbreads in Kokand.

iStock

The echoes of the Silk Road ring loudest in the valley’s vibrant bazaars and in its crafts – the paper factories of Kokand, the knives from Chust and the blue-and-green ceramics of Rishtan. The valley is one of the world’s oldest cultivated areas, and alongside the cotton fields there are orchards, vineyards, walnut groves and, of course, extensive mulberry tree plantations, which supply the valley’s silk factories with their raw material. Cotton and silk milling and the manufacture of chemicals and cement are among the valley’s most important industries; along the fringes are deposits of oil, natural gas and iron ore. The region’s natural resources contributed to the industrialisation of all Soviet Central Asia.

Home to one-third of Uzbekistan’s population, the modern Fergana Valley is the most densely populated part of Central Asia and its most religiously active centre. In recent years the valley has gained infamy as the centre of conservative Islam and of the government’s increasingly brutal attempts to stamp its control on the country. Further pressure came with the influx of 300,000 refugees from Kyrgyzstan following violence there in 2010 and the situation can be volatile.

Andijan

For travellers Andijan (Andijon in Uzbek transliteration) is the eastern gateway to the valley, a short hop and a skip from the Kyrgyz border near Osh. The city’s huge Thursday and Sunday bazaars have been attracting traders for millennia, but these days Andijan is most famous (rather, infamous) for the events of May 2005, when government troops massacred up to 1,000 unarmed demonstrators in the town’s central square.

There are several historical sites in town, such as the Babur Literary Museum, a former royal residence, but get advice on the current political climate before exploring too deeply. The Juma Mosque and Madrassa has long been a barometer of the shifting political tides, switching from Soviet-era museum to active madrassa and now back to secular museum.

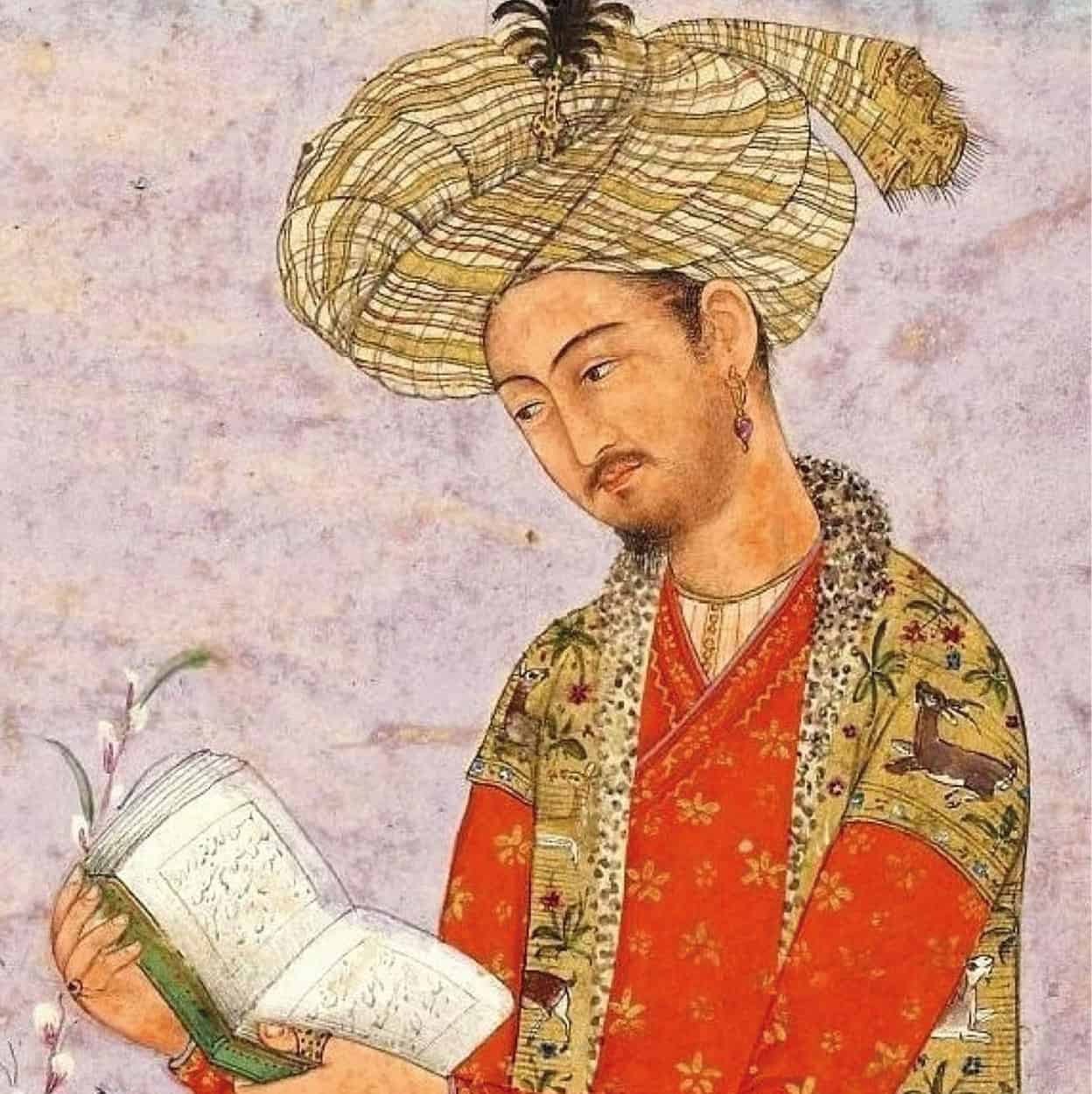

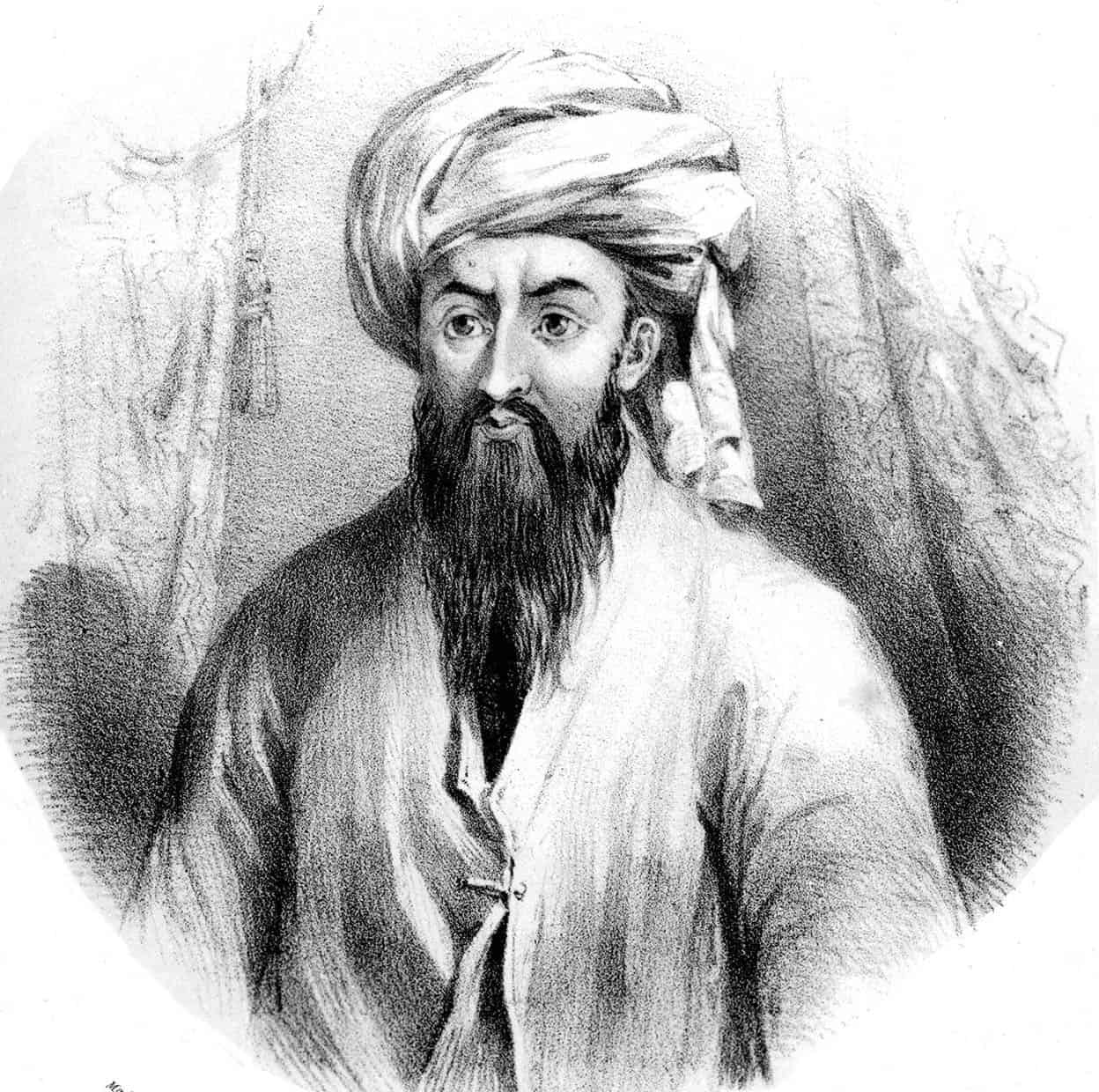

A 16th-century miniature portrait of Zahir-ud-Din Muhammad Babur.

Public domain

Fergana Town

In the south of the valley, also within striking distance of the Kyrgyz border, is the city of Fergana (Farg’ona in Uzbek). Founded as a Russian garrison town in 1876, it was initially named Skobelov after the Russian commander who subdued Khiva and Kokand and conquered the Turkmen tribes at the battle of Gök-Tepe. The blue-hued Tsarist buildings and colonial Russian layout of the town initially seem at odds with the traditional rural architecture of the valley, but the pleasant leafy boulevards, local museum and café-restaurants of the provincial capital make it a good base from which to explore the valley, and there are some good accommodation options, too.

Babur

A descendant of Timur and grandfather of the Mughal Emperor Akbar, Zahir-ud-Din Muhammad Babur (1483–1530) is an intriguing figure. Born in Andijan in 1483, he was forced out of his beloved Fergana Valley by the rising might of the Uzbek Sheybanids and fled to Afghanistan, conquering Kabul, Kandahar and finally India, where he founded the Mughal Dynasty. Despite his great conquests, he was never able to return to Central Asia, and his major literary work, the Baburnama, is infused with wistful longing for his beloved Fergana Valley. Though little-known today, without Babur the Central Asian-inspired architectural genius of the Taj Mahal and numerous other Mughal splendours in Delhi and Lahore might never have come to pass.

Margilan

Located just 5km (3 miles) to the north of Fergana, Margilan (Marg’ilon) was an important stop on the Silk Road. The local mulberry trees have fed silk production for centuries – even during Soviet times – and the economic life of the town is still dominated by the enormous Margilan Silk Factory, which churns out 2.5km (1.5 miles) of silk every day and employs some 15,000 workers. For a fascinating glimpse of traditional production methods, head to the Yodgorlik Silk Factory (daily 8am–5pm). Individual families raise the fussy silkworms on home-grown mulberry leaves, before the cocoons are taken to the factory to be steamed and unravelled and the silk woven into thread and then dyed. The result is the khanatlas (king of satin) or ikat, the brightly coloured blur that clads almost all Uzbek women. Also worth catching is the bustling Thursday and Sunday Kuntepa Bazaar, 5km (3 miles) west of the centre. Margilan’s atmospheric bazaar was replaced by a giant covered market in 2007. The few architectural remnants in town include the Khonakah Mosque, the Turon Mosque and the Sayid Akhmad Khodja Madrassa.

Namangan

Namangan, in the north of the valley, is the third-largest city in Uzbekistan. It is also known as its most religiously conservative, and its streets contain the highest concentration of veiled women in the country. The many closed madrassas and strong police presence highlight the government’s unease with the growth of Islam. If you are passing through the town, the terracotta facade of the Hadja Amin Kabri complex is particularly fine, as are the nearby ruins of Akhsykent, a 1st century AD settlement 25km west of the town.

Kokand

In the west, the Khanate of Kokand (Qo’qon in Uzbek) was long Central Asia’s third regional centre of power, for centuries jostling for regional dominance with Bukhara and Khiva, until the arrival of the Russians forced them all into irrelevance. At its peak, this crossroads city boasted 600 mosques and 15 madrassas, and ruled territory from the Kazakh Steppe to the Pamirs.

Only 19 opulent rooms survive from the original 113-roomed Palace of Khudayar Khan (built 1862–72), but it’s still worth a look (daily 9am–5pm; charge). The 100-metre (330-ft) -long iwan of the Juma (Friday) Mosque was built to house the city’s male population during weekly Friday prayers. Nearby is the Amin Beg Madrassa. Fifteen minutes’ walk east is the working Narbutabey Madrassa, behind which the royal cemetery houses the Modari Khan and Dakhma-i-Shakhon mausoleums – the tombs of Kokandi Khan Omar, his mother and his wife.

Routes west out of the valley lead naturally from Kokand to Samarkand via Khojand (in Tajikistan; for more information, click here); but today’s convoluted jigsaw borders mean that travellers generally head first to Tashkent, a three-hour drive away over the 2,268-metre (7,484-ft) Kamchik Pass. The newly strategic highway passes endless hairpin turns and snaking lines of crawling truck caravans to cross the Chatkal range, a faint final echo of the mighty Tian Shan.

Enjoying the shady terrace of a Kokand teahouse.

iStock

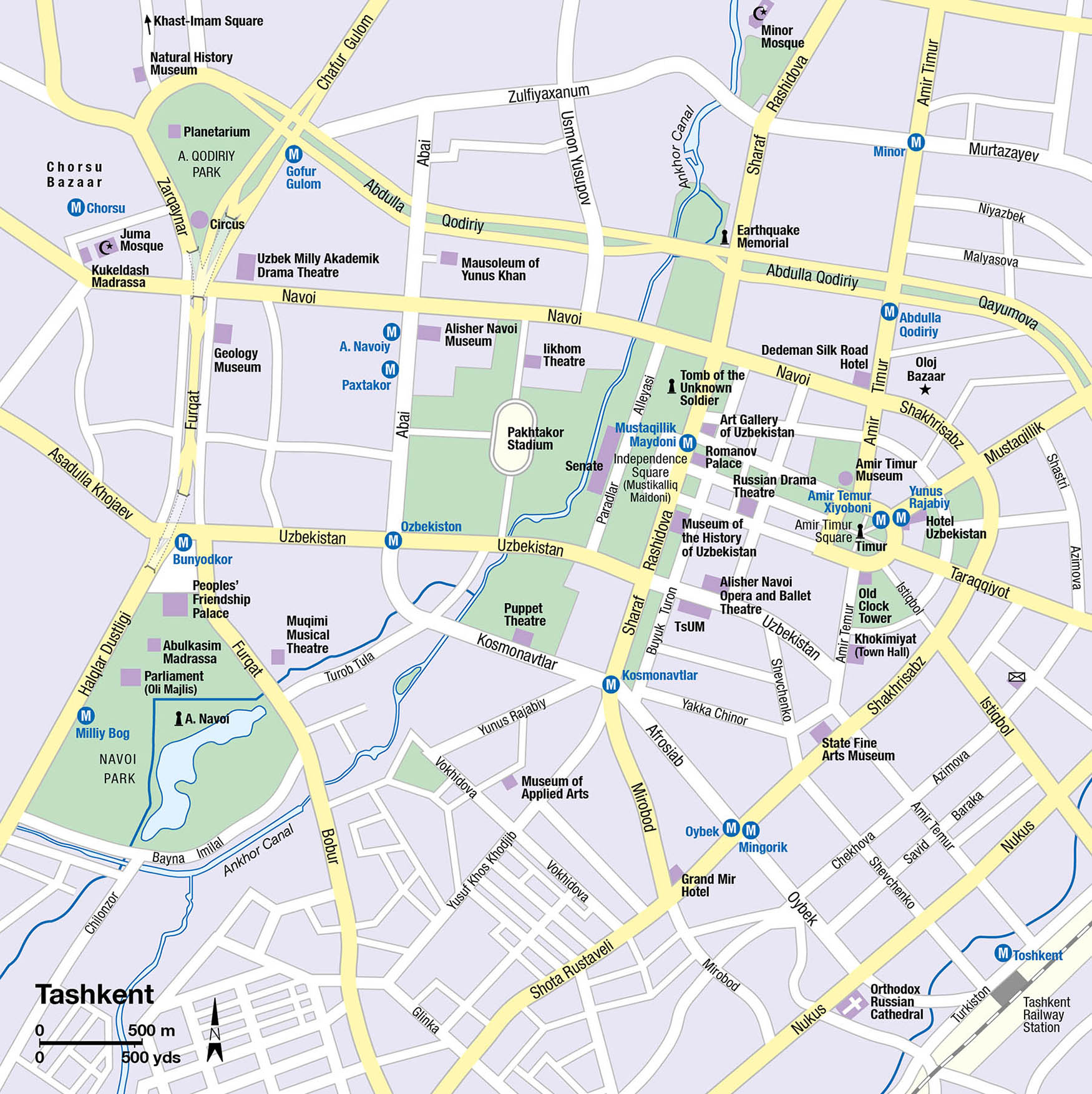

Uzbekistan’s capital is a huge sprawling city of over 2 million people; the largest in Central Asia and the fourth-largest in the former USSR. As a Soviet-era showcase of orderly boulevards, museums and monuments it’s not a particularly inspiring place but it’s worth a day or two’s exploration.

The city’s roots, at the foot of the Tian Shan, lie in the ancient caravan town that grew up at the border of the settled and nomadic worlds. Known initially as Chach, its name was changed by the Turkic-speaking Karakhanids to Tashkent, or Stone Village, in the 10th century. The Khanate of Kokand absorbed Tashkent in 1809, and in 1864 the Russian Tsarist General Chernaiev took the town with only 1,900 men, disobeying direct orders from his superiors in distant St Petersburg. The Russian military cantonment grew quickly under the first governor of Russian Turkestan, Konstantin Kaufmann.

The city became the capital of the Uzbek SSR in 1930, replacing Samarkand. World War II spurred rapid growth as evacuees and entire communities of deported Koreans and Germans were forcibly relocated here, along with much of western Russia’s heavy industry. The modern face of Tashkent (Toshkent in Uzbek) was transformed by the Soviet reconstruction that followed a powerful earthquake in 1966.

Tashkent’s ornate Amir Timur Museum.

Shutterstock

Central Tashkent

Icons of independence litter the centre of the city. The prime real estate outside the Hotel Uzbekistan, currently known as Amir Timur Square, is occupied by a park with a statue of Timur in the centre – the latest in a long line of iconic statues that have included Konstantin Kaufmann, Joseph Stalin and Karl Marx. The pleasant, leafy park is an ideal place to kick off a stroll of the city, dotted with shady glades where locals gather to play chess.

The iconic theme continues in the Amir Timur Museum, on the north side of the square. The modern turquoise-domed building, opened on the 660th anniversary of Timur’s birthday, is largely an exercise in propaganda, pairing the exploits of Timur with the cult of current president Karimov. The museum collection mainly consists of ancient manuscripts, paintings and engravings, but there are some fine wooden models of Timurid architecture from across Uzbekistan.

Further west, the huge Soviet-era parade ground of Independence Square (Mustikalliq Maidoni) was home to the Union’s largest Lenin statue until 1992, when it was replaced by a large globe whose only country is an oversized Uzbekistan. The square is the focus of colourful Independence Day celebrations that take place here each 1 September. Surrounding the square is the new senate building, the president’s office and various government ministries.

Tip

The best way to get around Tashkent is on the metro, which is worth riding for its stylish stations, dripping in decoration (in particular Kosmonavtlar with its floating cosmonauts). The system opened in 1977. Don’t take photos in the metro and watch out for policemen on the make, whilst acting as security guards at the entrances.

North from here is the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, which commemorates the 400,000 citizens of Uzbekistan who died in World War II. Nearby is the Earthquake Memorial, a poignant spot that marks the exact time and date in 1966 that a major earthquake levelled the town and left 300,000 homeless.

Tashkent has the best museums in Uzbekistan, including the Museum of Applied Arts (daily 9am–6pm; charge) and State Fine Arts Museum (currently closed), which is based on the private collection and palace of Prince Nikolai Romanov. Most worthy of your time is the Museum of the History of Uzbekistan (Tue–Sun 10am–5pm; charge), which houses some 250,000 exhibits including a Kushan-era Buddha statue from Fayaz Tepe, a decorated bronze cauldron from the 4th century BC and impressive coins and manuscripts. Further west, the Alisher Navoi Museum (Mon–Fri 10am–5pm, Sat until 1pm; charge) celebrates the poet whose major work (Khamsa) put Chaghatai Turkic on the literary map in an age when poets generally wrote only in Persian.

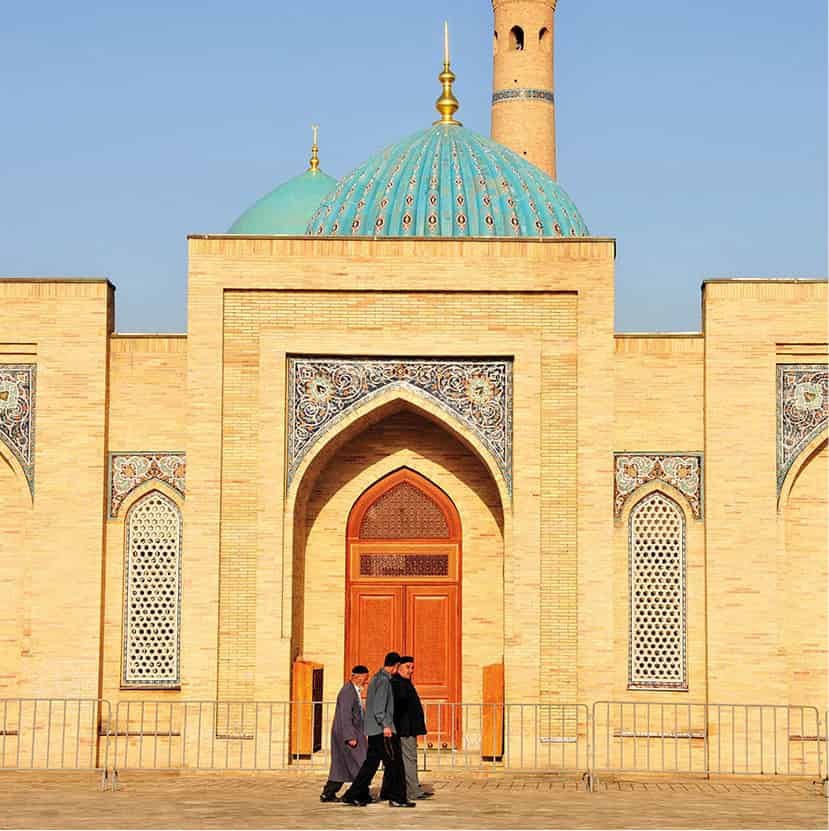

Two metro stations north of Amir Timur Square on the green Yunusabad line take you to Minor station and the brand new Minor Mosque. Built in 2014 and a beautiful marble structure, it is now the largest in the country and welcomes visitors.

Eat

Near Chorsu is the Chaghatai area of the city, where “home restaurants” are the order of the day. These family-run establishments offer simple dishes, such as kebabs, salads and soups, served with tea or beer. There are 120 versions of plov (palov or pilaf) in the country but delicious tuy plov can only be found in Tashkent.

Old Town

Tashkent’s Old Town (eski shakhar) doesn’t compare to Samarkand or Bukhara in either scope or style, but it’s worth a visit all the same. Start by taking the metro to the Chorsu (Four Roads) District and browsing the thunderous local bazaar, easily the city’s best, offering the souvenir black-and-white Uzbek skullcaps, colourful mounds of spices, famously sweet melons and huge naan breads served hot out of the tandur oven. A short walk to the east is the traditional-style Kukeldash Madrassa and Juma Mosque.

North from Chorsu, the Soviet boulevards quickly wither to winding alleys of mud-walled houses, and traditional Central Asian culture reasserts itself. Hidden here in the Old Town is the religious heart of the city, the Khast-Imam Square, home to the Imam Ismail al-Bukhari Islamic Institute, the highest seminary in the USSR and one of only two that operated in Uzbekistan during the Soviet era. The Mufti of Tashkent (the country’s top Islamic cleric) is based in the 16th-century Barak Khan Madrassa to the west.

Swimming in Tashkent’s central canal.

Shutterstock

Next to the nearby Tillya Sheikh Mosque, the affiliated Muyie Mubarek Library Museum (daily 9am–4pm; charge) holds an unexpected treasure, the world’s oldest Koran. The Osman Koran dates from 655, and the blood of the Caliph Osman still stains several of its deerskin pages. The caliph was murdered while reading from the Koran, something that further fuelled the split between the Sunni and Shia branches of Islam.

Back on Navoi Street, and opposite the Literary Museum, is the 15th-century Mausoleum of Yunus Khan, grandfather of the Mughal emperor Babur, in the grounds of the Tashkent Islamic University.

Fact

The chaos of the Bolshevik Revolution in Tashkent is described by F.M. Bailey in his book Mission to Tashkent. Bailey was in disguise when he passed through the city in 1918, and it must have been a pretty convincing one. At one stage the undercover British spy was given orders by the Russian secret police to hunt himself down!

Other sights

If you are in Tashkent outside the summer months, try to attend a performance at the lavish Alisher Navoi Opera and Ballet Theatre, designed by the same architect who built Lenin’s tomb in Moscow. Performances range from Puccini to Uzbek folklore. Check also to see what is playing at the Ilkhom Theatre, the most progressive arts venue in the country.

The lonely onion-domed Orthodox Russian Cathedral is worth a visit on Sundays for its fine icons. Since independence, large numbers of Tashkent’s Russian community have left Uzbekistan for a new life in Mother Russia.

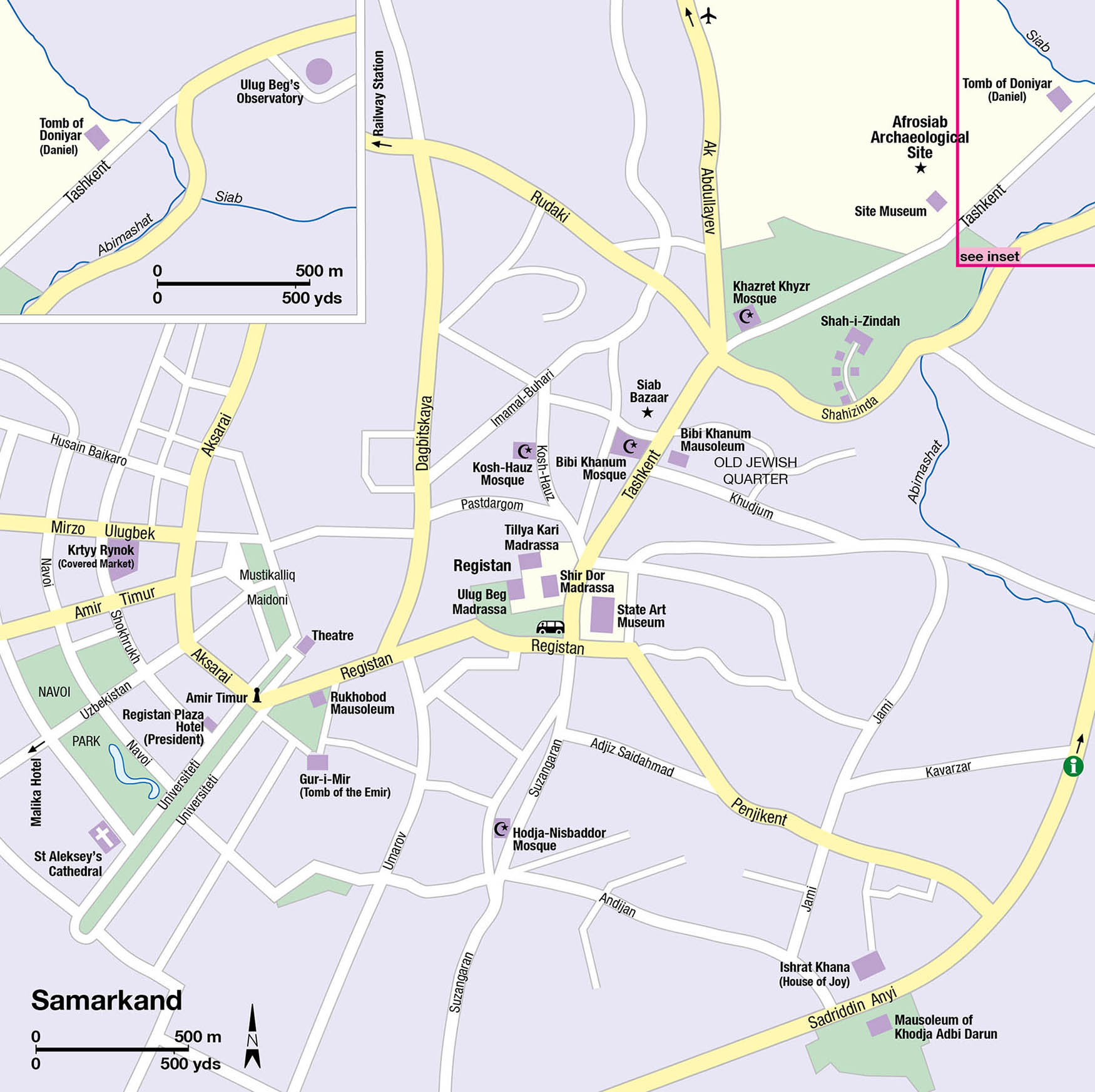

More so than any other city in Central Asia, Samarkand’s name drips with an exotic romanticism, whose resonance can be largely attributed to the immortal lines of James Flecker’s 1913 poem, Hassan:

We travel not for trafficking alone:

By hotter winds our fiery hearts are fanned:

For lust of knowing what should not be known

We make the Golden Journey to Samarkand.

Set at a trade crossroads and fed by the Zerafshan River, Samarkand (Samarqand in Uzbek) has been a Silk Road town for around 2,500 years. Alexander the Great visited in 329 BC, when it was the Sogdian city of Marakanda, part of the Achaemenid Empire. “Everything I have heard about Samarkand is true,” he said, “except it is even more beautiful than I had imagined.”

The world’s oldest Koran

You won’t be the only one surprised to hear that the world’s oldest Koran resides in Uzbekistan, and its journey here was a convoluted one indeed. It is known as the Osman Koran, after the caliph who compiled it in Medina in the 7th century.

In the 14th century Timur brought the Koran to Central Asia, from Basra, to display it on the central marble lectern of Samarkand’s Bibi Khanum Mosque. After the Tsarists took the city in 1868, the treasure was carted off to St Petersburg, until Lenin moved it on again, first to Ufa in Bashkaria and then to Tashkent’s State Historical Museum. Finally, in 1989, at the height of perestroika, the Koran was handed over to Islamic clerics at the Sheikh Tillya Mosque, where it remains to this day.

Passing by a mosque in the Sheikh Tillya Mosque complex, home to the world’s oldest Koran.

iStock

Sogdian wall murals recovered from Afrosiab in the northeast of the city depict the Silk Road heyday, when Tang China craved such exotica as Samarkand’s golden peaches. Xuanzang described Samarkand (So-mo-kien) in the 7th century: “The precious merchandise of many foreign countries is stored up here... The inhabitants are skilful in the arts and trades beyond those of other countries.”

The cosmopolitan city embraced Zoroastrian fire-worship and even became a Nestorian Christian bishopric until the arrival of the Arab armies changed everything in AD 712. The later invasions of the Khorezmshah and Mongol armies severely diminished the city. Marco Polo reported “a large and splendid city” at the end of the 13th century – but then he never actually saw it.

Samarkand is, above all, the city of Timur, and it is his turquoise domes and audacious building projects that draw visitors to this day. Timur forcibly relocated artisans from across his empire to embellish his capital, and it was in Samarkand that artisans from Persia, Azerbaijan, Syria and India saw “barbarism turned to beauty”. For Timur himself, the city was “less a home than a marvellous trophy”. Ever the nomad, he preferred the tents, camps and gardens outside the city walls to the epic bricks and mortar inside.

Silk Road traffic dried up from the 16th century, and Samarkand gradually took a back seat to Bukhara. The city was taken by the Russians in 1868 and shone briefly as the capital of the Uzbekistan SSR until sinking into obscurity as a remote corner of the Soviet Union.

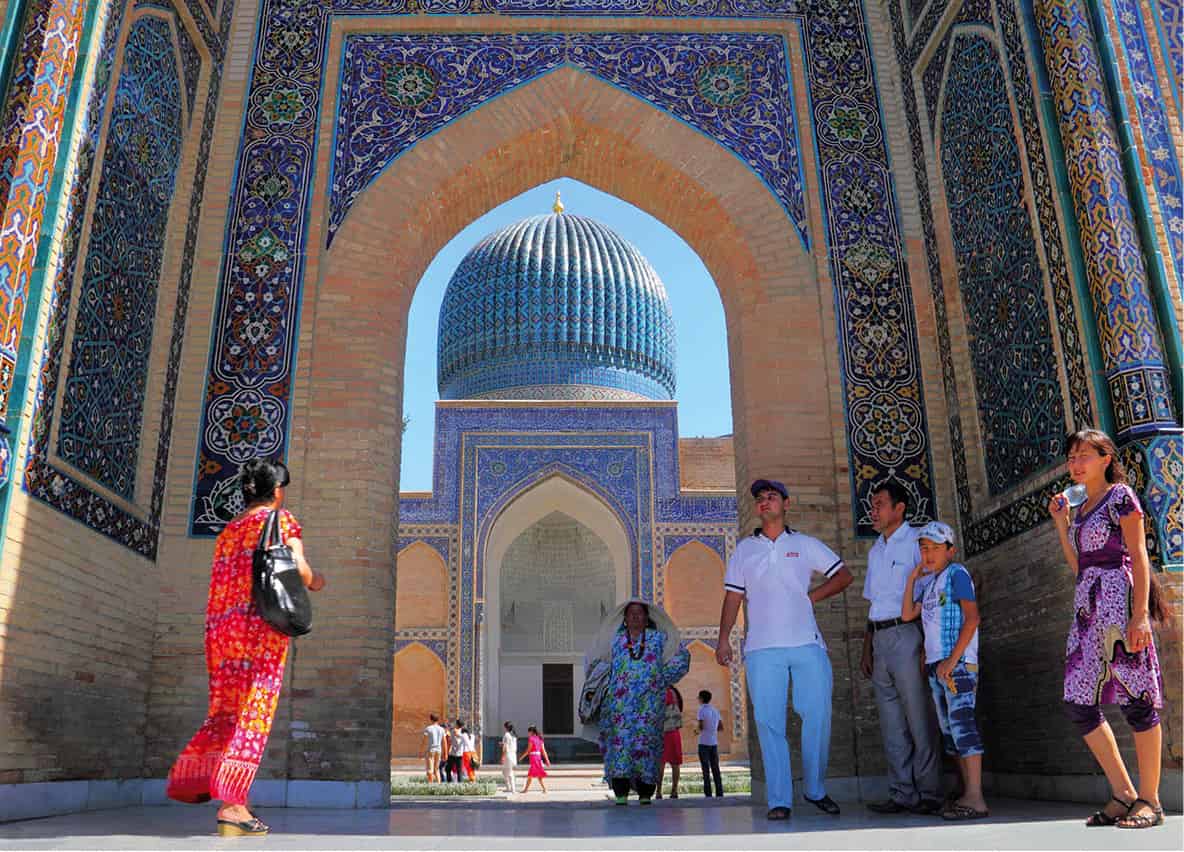

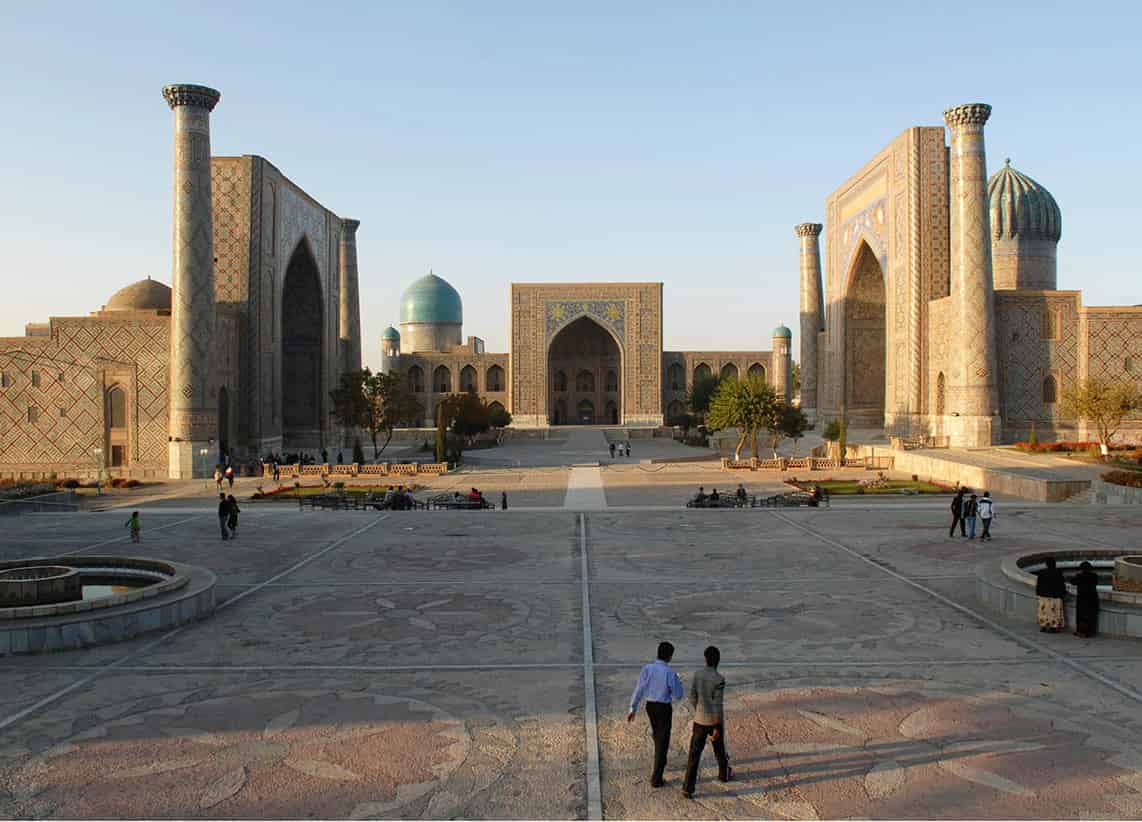

Samarkand’s Registan (daily 8am–7pm; charge) is without doubt the single most dramatic architectural ensemble in Central Asia. Three towering madrassas, saturated from head to toe in mesmerising tilework, rise around open ground to form an irresistible symmetry. The British MP (and future viceroy of India) George Curzon called it “the noblest public square in the world”.

The Registan (“Sandy Place”) was originally a market area, where the six roads of the city met in a trade crossroads. It was later used for military parades and public executions, while the Bolsheviks used it for political rallies, trials and veil burnings. Now beautifully restored, it offers a fabulous and recently upgraded, high-tech evening sound-and-light show, much better than the previous version.

The Bibi Khanum Mosque.

Shutterstock

Ulug Beg built the first madrassa here (1417–20), on the west side, flanked by 33-metre (109-ft) -high columns and richly decorated with star designs, girikh (geometric) patterns, and stunning mosaic and majolica tilework. If you tip the security guard downstairs, it is possible to climb the right-hand minaret and exit on to the roof, from where there is a superb view across Samarkand. It was a further two centuries before the Shir Dor Madrassa (1619–36) was erected to the east as a mirror piece. The madrassa gets its name from the mosaic lions (shir) that adorn the corners of the portal – anatomically incorrect, you’ll be forgiven for thinking they’re tigers. The flouting of the Islamic convention against the depiction of living beings is made doubly heretical by the beaming Zoroastrian-inspired sun faces painted on the lions’ backs.

The ensemble is topped off by the Tillya Kari Madrassa (1646–60), wider than the other two and boasting a huge turquoise dome and magnificent gilded interior. The former hujra (student accommodation) cells now function as gift shops and you can watch artisans at work. The nearby four-sided Chorsu was once the city’s skullcap bazaar.

The State Art Museum (daily 9am–6pm; charge) on the east side of the Registan displays copies of Afrosiab’s murals and the famous Kushan-era Ayrtam frieze (discovered near the Afghan border), as well as Timur’s wooden coffin.

Tamerlane, “Conqueror of the World”.

Getty Images

Tamerlane the Great

Few individuals shaped Central Asia as much as Tamerlane, a merciless leader who conquered lands from India to Baghdad.

Born into the Barlas clan of Turkicised Mongols only a century after the death of Genghis Khan, legend suggests that Tamerlane’s palms were filled with blood, auguring a bloody life. He started his career as a bandit, and at the age of 27 he was shot with an arrow in his right shoulder and hip while rustling sheep. His wounds gave rise to his pejorative Persian nickname Timur-i-Leme (Timur the Lame) and the later Latinised version, Tamerlane.

Timur’s ambitions were not easily contained, and by 1370 he had vanquished his former brother-in-law to be crowned ruler of Chaghatai – “Conqueror of the World”. He proclaimed, “The world is not large enough for two kings”, and for the next 35 years he tried to prove that claim. He defeated the Ottoman sultan Beyazid in Ankara, destroyed the Golden Horde on the Kazakh Steppe, and wrested control of trade routes from Delhi to Damascus.

It has been estimated that Timur’s merciless campaigns led to the deaths of 17 million people. Prisoners in Isfizar in Iran were cemented alive into giant towers. His troops bombarded the Christian armies at Smyrna with cannonballs made from the severed heads of their own knights. He boasted that his troops beheaded 10,000 Hindus in a single hour during the plunder of Delhi. In Baghdad in 1401 his forces killed 90,000 locals and cemented their heads into 120 towers.

A great legacy

Though he remains little-known in the West, his reputation alone was enough to inspire poetry by Edgar Allan Poe (Tamerlane), drama by Christopher Marlowe (Tamburlaine the Great) and operas by both Handel and Vivaldi (Il Tamerlano). Like all the great nomad leaders, Timur suffered the fate of being chronicled almost exclusively through the jaundiced eyes of his victims.

The man himself is in many ways a contradiction. Islamicised and Turkicised, he was a Muslim, though he never let his religion get in the way of his conquests. He spoke both Persian and Turkic fluently and had a great respect for learned men, yet he himself was illiterate. A nomad at heart who lived on the move, he also created some of the most beautiful urban architecture the world has ever seen. A chess fanatic, he invented a new game that employed twice the number of pieces (including camels, giraffes and war engines). Historians estimate that he had at least 12 wives.

Timur died in February 1405 in Otrar while planning his biggest campaign yet, the invasion of Ming China. His body was “embalmed with musk and rose-water, wrapped in linen, laid in an ebony coffin and sent to Samarkand”. His body was interred in the Gur-i-Mir and his howls were allegedly heard nightly for a year after his burial. Today, Uzbekistan celebrates their most famous son with three giant bronze statues in the cities most associated with him. In Shakhrisabz, he stands defiantly in front of the remains of his Ak Sarai Palace; in Samarkand, he is in a more reflective seated pose near to his tomb; and in the middle of Timur Square in Tashkent, he proudly waves to the crowds riding his horse, near to his own museum. Perhaps his most fitting epitaph is inscribed on his tomb: “If I were alive,” it reads, “people would not be glad.”

Bibi Khanum Mosque

Timur made his true bid for architectural immortality with the Bibi Khanum Mosque (daily 8am–7pm; charge), a monumental building planned on a hitherto unseen scale, along the pleasant pedestrianised street northeast of the Registan. Financed from the spoils of a recent campaign to Delhi (1398) and built with the labour of 95 imported Indian elephants, the huge 35 metre- (116 ft-) entry arch was flanked by 50 metre- (165 ft-) minarets that led into a court paved with marble and flanked with mosques. But it was built in too much haste (Timur himself threw gold coins and scraps of barbecued meat to encourage workers), and the tottering walls started to crumble almost as soon as they were finished. In the last decade, a similarly hasty programme of restoration has rebuilt the three main domes – “a shining blandness”, in the words of Colin Thubron, “snuffing out the strange vitality of ruin”.

Fact

When Alexander the Great swept into Central Asia he took Samarkand, then known as Maracanda, in 329 BC. It was already a well defended administrative centre belonging to the Persians.

The Registan in Samarkand.

iStock

The mosque was built in honour of Timur’s chief wife, Saray Mulk Khanum, who was laid to rest in the nearby Bibi Khanum Mausoleum. A number of local women still come here to pray, although it is now considered a museum rather than a place of worship. Next to the mosque is the main Siab Bazaar, groaning with grapes, fruit and, yes, Samarkand’s famed golden peaches. There is a pleasant picnic spot between the mosque and the market. A short walk north leads to the Khazret Khyzr Mosque, an elegant structure with carved wooden pillars and jewel-coloured paintwork, named after the pre-Islamic patron saint of wayfarers.

Shah-i-Zindah and around

Samarkand’s other great artistic highlight is the Shah-i-Zindah (daily 8am–7pm; charge), a visually absorbing necropolis and one of the great masterpieces of Timurid art. The street of tombs, accessed from the main road or on foot via the city’s modern graveyard, dates from 1372 to 1460 and houses a veritable “Who’s Who” of Timurid aristocracy, including Timur’s niece Shadi Mulk Aka, sisters Turkhan Aka and Shirin Bika Aka, and wives Tuman Aka and Kutlug Aka.

The tombs’ real genius lies in their range of decoration, with carved terracotta and majolica tilework set into complicated floral designs framed with stylised calligraphy, everything saturated in a dozen intense shades of blue. The focus for local pilgrims is the tomb of the Arab leader Kusam ibn Abbas, who was beheaded after his attempts to convert locals to Islam and merged into the local pre-Islamic legend of the “Living King” (Shah-i-Zindah). Come shortly before dusk for the most atmospheric experience.

The interior of Gur-i-Mir.

iStock

One of the few remnants of the early Silk Road are the ruins of Afrosiab, the Sogdian city that flourished from the 6th century BC until the arrival of Genghis Khan in 1220. It was here that the increasingly megalomaniac Alexander the Great killed his favourite general, Cleitus, in a drunken rage. Excavations of the dusty 120-hectare (300-acre) site have revealed Graeco-Bactrian and Kushan roots, Zoroastrian temples and a cult centre dedicated to the local god Anahita, though there’s little to see these days except hot dusty trenches and low excavated walls. However, the museum (daily 9am–6pm; charge), housed in the modern Soviet-era building at the site, is fascinating, and guides (some speaking English) provide informative talks on the different periods.

Afrosiab is most famous for its wall murals (long since removed), which feature a royal bridal procession atop a white elephant, a series of bearded ambassadors to the Sogdian court and a ruler in magnificent clothes meeting with silk-bearing Chinese, Turkic and even Korean envoys. Copies of these murals are also on display at the museum. The site is named after the legendary king depicted in Firdausi’s epic poem Shahnameh (“Book of Kings”).

Adjacent to the site is the Tomb of Doniyar (Daniel), where a local legend claims that the bones of the Hebrew saint were interred after Timur brought them to Samarkand.

The most enlightened of the Timurid rulers was without doubt Timur’s grandson, the “Astronomer King” Ulug Beg. Ulug Beg’s penchant for astronomy, mathematics and science didn’t go down well with the conservative court of the day, and he was eventually beheaded by his own son. In 1908 Russian archaeologists unearthed Ulug Beg’s Observatory, commissioned in 1428 and destroyed by fanatics 21 years later. The underground chamber was excavated by the Soviets in 1938. You can still see the lower one-third of the arc of the great sextant cut into the rock, and the nearby museum helps to explain how it all worked. A poignant inscription outside proclaims: “The religions disperse, kingdoms fall apart, but the work of science remains eternal.”

Ulug Beg

As the ruler of Samarkand, the Timurid ruler Ulug “Mirzoi” Beg (1394–1449), grandson of Timur (for more information, click here), built several of the city’s most beautiful madrassas. However, it is his scientific patronage, and in particular his magnificent observatory, the Gurkhani Zij, for which he is most renowned. Like the Khwarezmian scientist al-Biruni 400 years before him (for more information, click here), Ulug Beg was the finest astronomer of his age, correctly repositioning 1,018 stars in an astronomical catalogue that was the first of its kind since Ptolemy. Tragically, within two years of his father Shah Rukh’s death he was assassinated while on his way to Mecca, a martyr to science, and was laid to rest in his grandfather’s tomb, the Gur-i-Mir.

Ulug Beg dispensing justice at Khurasan (15th-century miniature).

TopFoto

Samarkand’s final “must-see” is the Gur-i-Mir (Tomb of the Emir), the final resting place of Timur. The mausoleum was originally planned for Timur’s favourite grandson, Muhammad Sultan (Timur had long wanted to be buried in Shakhrisabz), but Samarkand was deemed a more fitting resting place. The exterior of the building is dominated by a fine entrance portal and the hallmark ribbed turquoise dome that floats like a giant balloon above the central octagonal chamber. It’s a beautiful but surprisingly modest monument for the world’s greatest warlord. Timur is buried at the foot of his spiritual adviser, Mir Sayid Barakah, and surrounded by many of his family. His body lies under a tombstone that was at the time the world’s largest slab of jade. The Persian invader Nadir Shah broke the slab while trying to steal it. The actual graves are in the crypt below.

Two other tombs are located within the Gur-i-Mir area: the 14th century Rukhobod Mausoleum, which is said to contain a hair of the Prophet, and the unrestored brick-built Aksaray Mausoleum on the street behind.

Other sights

Other architectural gems in the Samarkand suburbs include the Mausoleum of Khodja Abdi Darun, built by Seljuk Sultan Sanjar and renovated by Ulug Beg, and the nearby Ishrat Khana (House of Joy), a refreshingly unrestored pleasure dome built by Timur’s wife and later converted into a mausoleum by one of Timur’s descendants.

South from Samarkand, modern roads follow a side branch of the Silk Road to the Oxus River. The route was popular with invaders and traders, and the latter were taxed at a defile en route known as the “Iron Gates”.

The town of Shakhrisabz, 80km (48 miles) south of Samarkand over the Takhtakaracha Pass, is most famous as the hometown of Timur, who was born nearby in April 1336. His actual birthplace is in Khoja Ilgar Village, some 13km (8 miles) to the south, where a surprisingly unassuming cairn marks the spot.

Today Shakhrisabz is a charming, traditional Uzbek town, littered with the ruined monuments of its favourite son. The Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang visited when it was known as the Sogdian town of Kesh. Tajik-speakers later renamed it Shahr-i-sabsz, the “Green City”.

The White Palace

The main sight is the huge ruined complex of the Ak Serai, Timur’s “White Palace”. Built by slave artisans brought here from Khwarezm, the site was planned as a summer residence to complement Samarkand’s Kok Serai, or Red Palace.

The restorers have again been hard at work here, trying to recreate the huge 65-metre (214-ft) entry towers that once supported Central Asia’s largest portal. The incredible palace was visited in 1404 by the Spanish envoy Ruy González de Clavijo, who described the palace’s blue-tiled walls, golden ceilings and the lush surrounding gardens of waterfalls and silk tents that were the site of epic Bacchanalian feasts of wine and horseflesh. By the time Clavijo arrived craftsmen had already been working on the palace for over 20 years.

A large statue of Timur dominates this newly pedestrianised and landscaped complex. Here the words of Timur resonate: “Let he who doubts our power look upon our buildings.”

Timurid tombs

Other buildings worth visiting as you walk south are the 14th-century Malik Azhdar Khanaga and the Amir Timur Museum, housed in a former madrassa. The impressive blue dome in the south of the town belongs to the Kok Gumbaz Mosque (1435–6), built by Ulug Beg as part of the Dorut Tilovat complex. Timur’s father Taraghay and his spiritual adviser Shamsaddin Kulyal are both buried in the nearby Timurid mausoleum.

A couple of minutes’ walk to the east is the crumbling Tomb of Jehangir, all that remains of the Dorus Siadat, a Timurid family memorial that ranked as one of Timur’s greatest creations. Timur’s eldest son Jehangir and second son Umar Sheikh are both buried here, and Timur himself also planned to be interred here. The intended crypt of Timur was discovered nearby in 1943, and you can still see the empty underground marble casket.

From Shakhrisabz, the main M39 road continues southeast to the border city of Termiz, from where the Friendship Bridge leads across the Oxus to the Afghan cities of Mazar-e-Sharif and Balkh, themselves both ethnically Uzbek.

Ak Serai in Shakhrisabz.

iStock

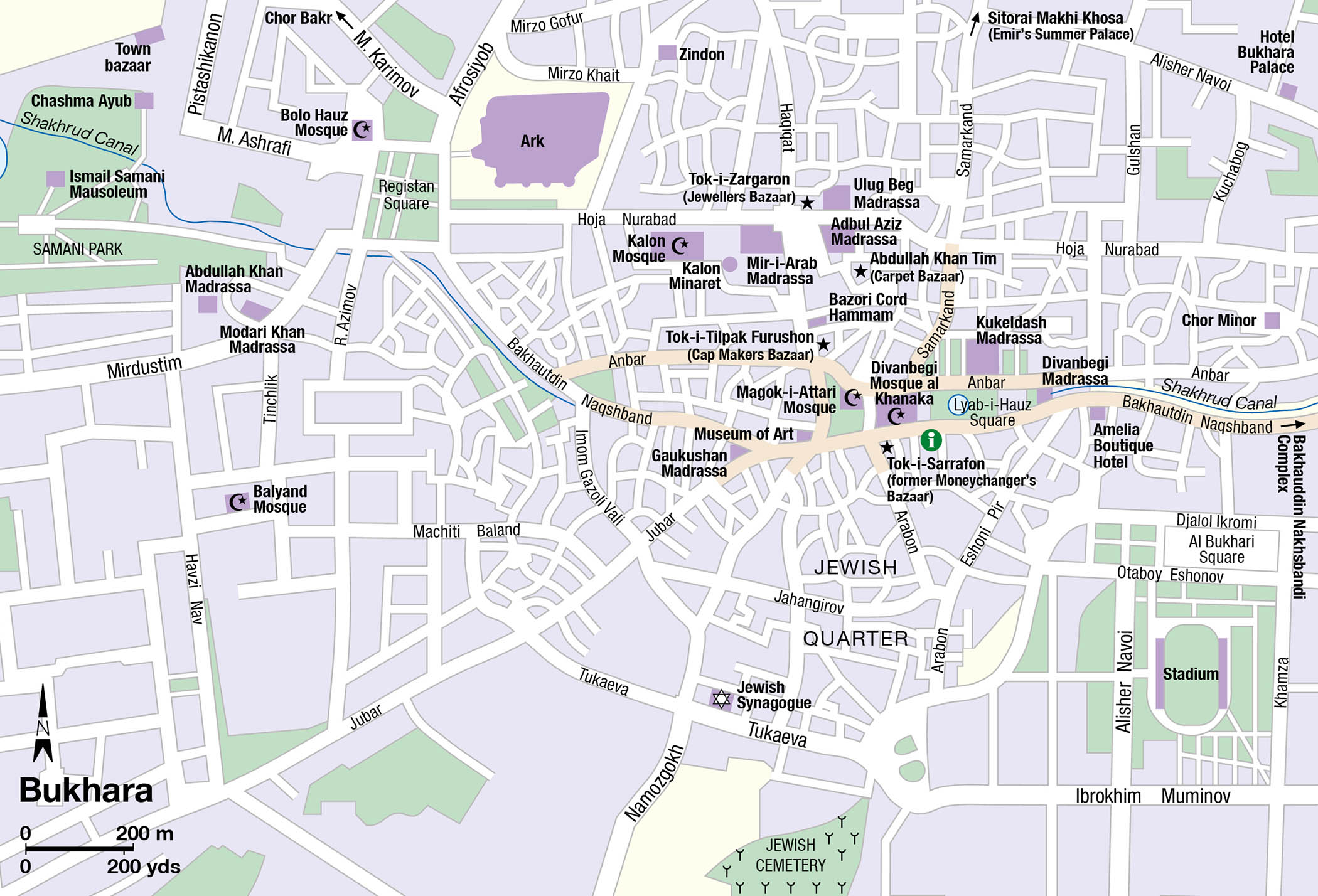

Known for centuries as Bukhoro-i-sharif (Bukhara the Noble), and the “Dome of Islam”, the holy city of Bukhara (Buxoro in Uzbek) is one of the oldest cities in Central Asia, stretching back some 2,500 years. At its peak the city boasted 250 madrassas, 200 minarets and a mosque for every day of the year.

According to the Persian epic Shahnameh, the hero Siyavush founded the city after marrying the daughter of neighbouring Afrosiab. The town thrived as a transit spot and a crossroads town, with city gates pointing to Merv, Gurganj, Herat, Khiva and Samarkand.

In the early days Bukhara was eclipsed by great cities now lost in the surrounding deserts. All that remains of Varakhsha, once the richest caravan stop in the region, are the superb Sogdian murals, now preserved in local museums, of hunters battling leopards and a court scene flanked by winged griffins. The Hephthalite capital of Paikend, another of the great regional trading centres, was destroyed during the Arab invasion.

Bukhara hit its high point in the 9th and 10th centuries under the Samanid Dynasty, when the city became a great centre of Persian culture and science. Thinkers such as al-Biruni, the poet Rudaki and the medic Ibn Sina (Avicenna), Bukhara’s grand vizier for a time, enjoyed access to Bukhara’s “Treasury of Wisdom”, a library surpassed in the Islamic world only by the House of Wisdom in Baghdad.

The city was largely destroyed by the Mongols in 1220. Genghis Khan addressed the trembling citizens of Bukhara with a perverse sense of logic: “If you had not committed great sins,” he said, “God would not have sent a punishment like me.” When the Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta arrived in Bukhara a century later in 1333, the city was still in ruins.

The khanate (and later emirate) was revived in the 16th century under the extensive building programmes of Abdullah Khan, but by the Astrakhanid Dynasty the decline of the Silk Road had isolated Bukhara, and the city began a gradual slide into decay and fanaticism.

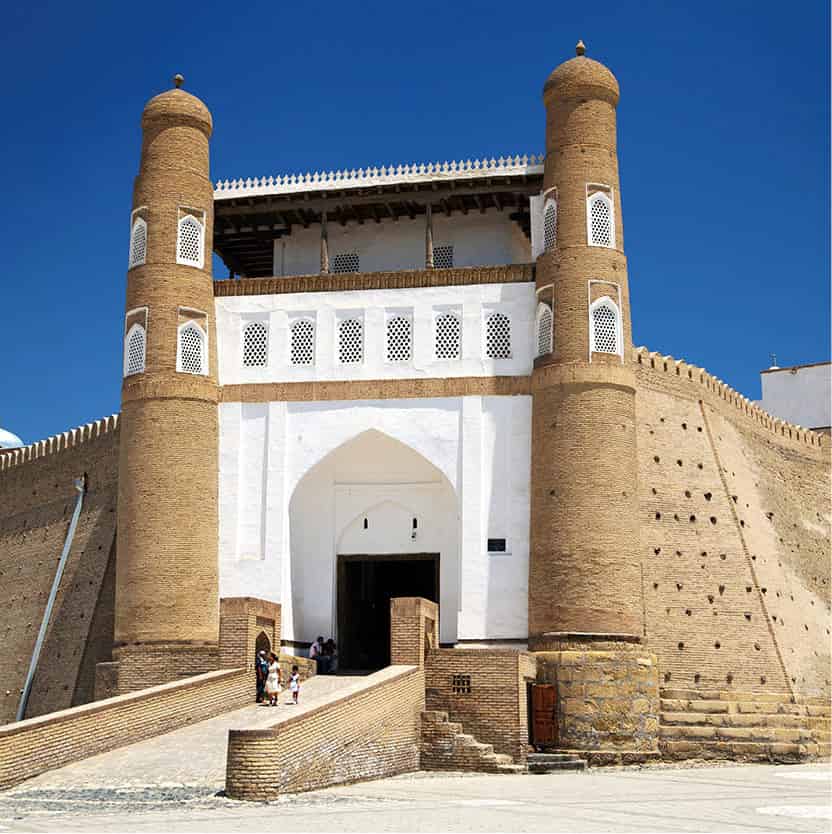

A city within a city: Bukhara’s ancient Ark.

iStock

The 19th century brought intrepid travellers to the city. The great traveller William Moorcroft arrived in 1825 in search of horses but left empty-handed, only to be murdered on the return journey to Balkh. Alexander “Bokhara” Burnes, later to write his classic travelogue Travels into Bukhara, visited the city in 1832. The city gained true notoriety abroad when the British officers Conolly and Stoddart were executed in Bukhara in 1839. Bukhara’s glory days were coming to an end. Even in the 19th century foreign travellers described the city as wearing “a halo of departed glory”.

Today the quiet and largely Tajik town offers plenty of scope for exploration. If you have only one spare day in your itinerary, spend it here. The domes and minarets of the sun-dried city glow golden in the afternoon light, and although a little lacking in spice, exhausted by its long Soviet rule, the city’s twisting backstreets still provide plenty of Silk Road atmosphere.

The Ark

The heart of ancient Bukhara is the Ark (daily 9am–6pm; charge), the 2,000-year-old fortress around which the city formed. Fortified, destroyed and rebuilt many times over the years, the “city within a city” became home to the emirs of Bukhara, evolving into a complex warren of chambers, mosques, reception rooms, servants’ quarters, mint, jail and armoury. What remains today is only about 30 percent of the original; peek around the back to see the ruins left by the Red Army artillery of General Frunze in 1920.

Restoration work

War, neglect and an extreme climate have taken a heavy toll on Uzbekistan’s architectural gems. By the end of the 19th century, many of Samarkand’s domes and Bukhara’s minarets had started to collapse. Early Soviet archaeologists painstakingly restored Bukhara’s Ismail Samani Mausoleum, and Samarkand’s Registan to their former glory, but sadly these monuments are again under threat. A rising water-table is driving salt into Bukhara’s brickwork, it’s common to see grass growing and birds nesting amongst the tiles, and the clumsy reconstruction of sites like the Bibi Khanum Mosque in Samarkand is damaging Uzbekistan’s golden cities. Scaffolding, though essential to repair work, regularly blights domes across the skyline.

The main entrance leads up a ramp into the great 18th-century gatehouse, or darvazkhana, above which the emir’s retinue would watch executions and public events in the square below. The Bukhara State Art and Architectural Museum occupies the Friday mosque and the former 17th-century coronation room, and displays 18 permanent exhibitions of paintings, manuscripts, coins and ethnographic items.

Outside the Ark, at the foot of the baked brick walls, is Registan Square, home to the city’s slave market, parade ground and, when a drumbeat pulsed from the depths of the Ark, its flogging and execution ground. The elegant colonnaded iwan of the Bolo Hauz Mosque rises to the north.

Around the back of the Ark is the Zindon, the former city jail, where important prisoners were held, often for years at a time. You can still see the notorious “Bug Pit” where the British officers Conolly and Stoddart were held for months before being executed.

South of the Registan are the Abdullah Khan Madrassa (1588) and Modari Khan Madrassa (1567), the latter built for the mother (modar) of the Uzbek Khan Abdullah Sheybani (1533–97). Further south is the multicoloured Balyand Mosque, noted for its gilded kundal paintings.

Quote

“A stranger has only to seat himself on a bench of the Registan, to know the Uzbeks and the people of Bokhara. He may here converse with the natives of Persia, Turkey, Russia, Tartary, China, India, and Cabool. He will meet with Toorkmuns, Calmuks, and Kuzzaks, from the surrounding deserts, as well as natives of more favoured lands.”

Alexander Burnes on 19th century Bukhara

Samanid Mausoleum

A five-minute walk west of the Ark brings you to Samani Park, which is home to one of Central Asia’s great architectural highlights, the Ismail Samani Mausoleum. The 10th-century gem houses the tomb of Ismail Samani, founder of the cultured Samanid Dynasty that oversaw Bukhara’s cultural highpoint. The genius of the cubed building lies in its elegant basket-weave brickwork, which glows in full glory in the afternoon light.

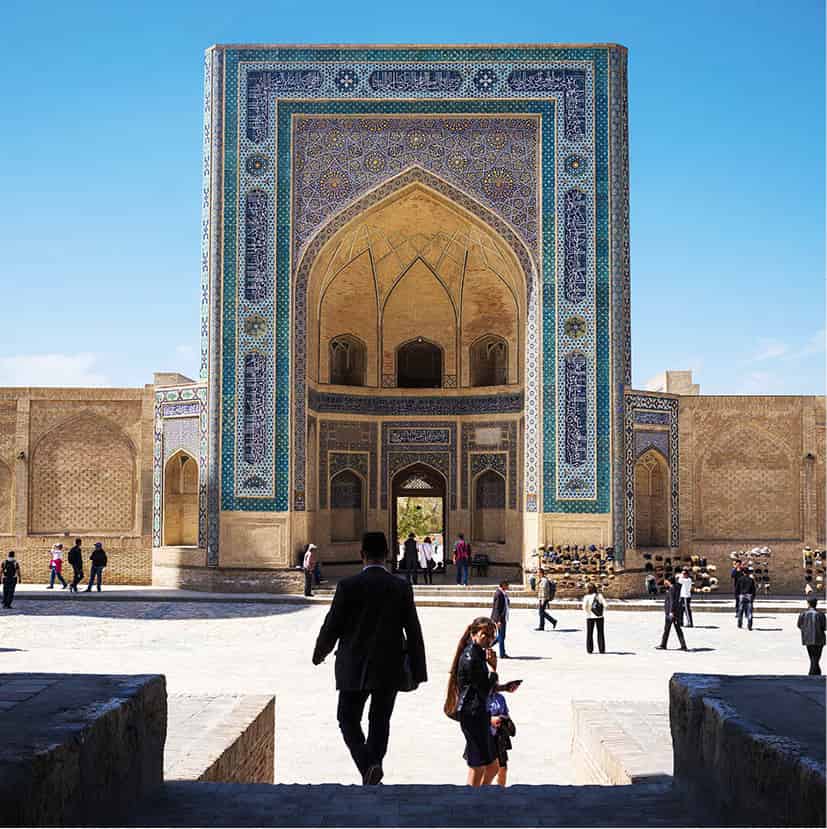

The imposing Kalon Mosque in Bukhara.

iStock

Nearby is the Chashma Ayub, built in 1380 around the spring of the Old Testament prophet Job (Ayub in Arabic). The conical cupola, unique in Bukhara, was designed by artists relocated from Gurganj (Kunya-Urgench) by Timur. The town bazaar is next door.

Bukhara’s most impressive building is the Kalon Minaret (Kalon meaning “great” in Tajik). Built in 1127 by the Karakhanid ruler Arslan Khan, the tower was probably the world’s tallest building at the time of its construction. Even Genghis Khan was awestruck, ordering the building spared from the Mongol destruction. It is the only building of this period to survive in Bukhara.

The minaret rises 48 metres (158ft) through bands of intricate brick patterns and is connected to its mosque roof by a bridge passage. The single turquoise band towards the top is thought to be the earliest example of glazed tilework in Central Asia. The minaret was nicknamed the “Tower of Death” in the 19th century, when criminals were tied in sacks and hurled off the skylight by orders of the Emir.

View of the Kalon Minaret from the Ark.

iStock

The attached Kalon Mosque (admission charge) was for centuries Bukhara’s main Friday mosque, built to accommodate over 10,000 worshippers. The town’s first Arab governor built the earliest mosque on this spot. A later 12th-century building was set ablaze by the Mongol forces but was rebuilt in 1514. When Genghis Khan arrived at the holy site he turned the mosque into a stable and uttered “The hay is cut. Give your horses fodder”, the signal for his troops to pillage the city. The mosque still has its 288 cupolas, of which the largest is the gorgeous Kok Gumbaz (Blue Dome) at the west end. The mosque was used as a warehouse during the Soviet era.

Across from the mosque are the twin turquoise domes of the Mir-i-Arab Madrassa (1535), one of only two such institutions to function in Uzbekistan during the Soviet era. The building was financed by Ubaidullah Khan from the sale of 3,000 Persian slaves and is named after the khan’s Yemeni spiritual adviser (Mir-i-Arab means “Lord of the Arabs”). Both adviser and Khan are buried inside. This is still a working madrassa, and so the fine interior is off-limits to tourists.

Fact

In 1938 Fitzroy Maclean arrived into Bukhara almost a century after the Conolly and Stoddart incident. In Eastern Approaches he wrote, “I could have spent months in Bokhara, seeking out fresh memories of its prodigious past, mingling with the bright crowds in the bazaar, or idling away my time under the apricot trees in the warm sunlight of Central Asia.”

To the south of the madrassa is the small Emir Alim Khan Madrassa, now a children’s library.

To the east is the Ulug Beg Madrassa (1417), Central Asia’s first madrassa and the prototype for the version that Ulug Beg was to build three years later in Samarkand’s Registan Square. Ulug Beg’s love of astronomy and science is revealed in the star-shaped motifs and the inscription above the portal that states: “It is the sacred duty of every Muslim man and woman to seek after knowledge.” The madrassa was renovated during its 500th anniversary in 1994.

The unrestored Abdul Aziz Madrassa (1652) across the road boasts fine Chinese-influenced interior decoration and a woodcarving museum. Both madrassas follow a standard design, with a mosque and lecture hall on either side of an entrance portal and a series of student cells arranged around the inner courtyard.

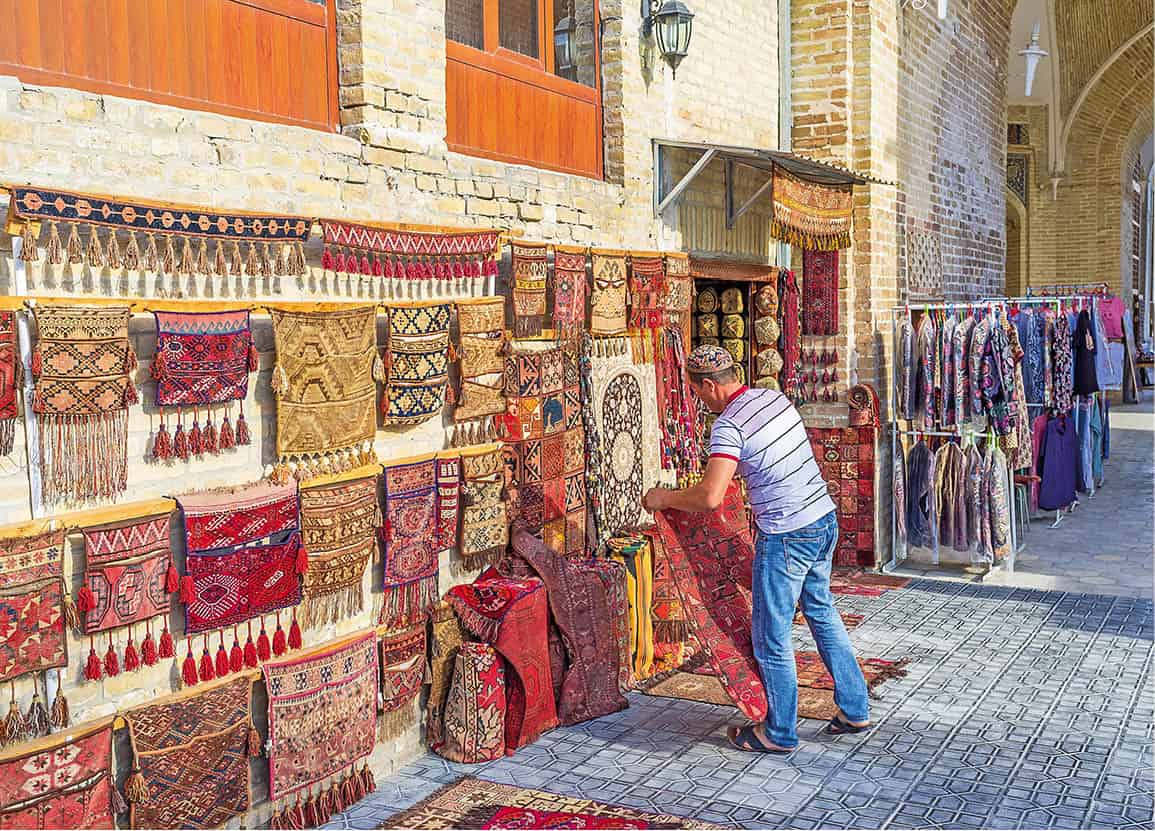

A Bukhara carpet-seller.

iStock

Bukhara’s bazaars

The heart of any Silk Road city lies in its bazaars and Bukhara once boasted 40 of them, along with 24 caravanserais, six tims (trading houses) and three toks (multi-entried bazaars that straddle major intersections). Though the turbaned traders of old have been replaced by souvenir-sellers, the cool, domed covered bazaars still offer a glimpse of the bones of a medieval Central Asian bazaar. Most of the buildings in this part of town house small exhibitions, craft workshops or souvenir stands, sometimes all three.

The main thoroughfare leads south from the Tok-i-Zargaron (1570, Jewellers’ Bazaar), which once cornered the local market in lapis and rubies from Badakhsan, past the long-vanished Indian caravanserai to the Abdullah Khan Tim, which once specialised in wool and silk, and now, appropriately, sells carpets.

South of here is the 16th-century Bazori Cord Hammam, a bathhouse still open for men and tour groups who reserve it in advance. Also here, dominating the five-spoked intersection, is the Tok-i-Tilpak Furushon, or Cap Makers’ Bazaar, which once specialised in gold-embroidered skullcaps, fur hats and illustrated manuscripts, all of which had to be protected from the glare of the sun. Inside the bazaar is the tomb of holy man Khoja Ahmed I Paran.

Fact

“Bokhara! For centuries it had glimmered remote in the Western consciousness, the most secret and fanatical of the great caravan cities, shored up in its desert fastness against time and change.” Colin Thubron features Bukhara in two of his most popular books, Shadow of the Silk Road and The Lost Heart of Asia.

To the side, between the two domed bazaars, is the Magok-i-Attari Mosque, one of the earliest religious shrines in the city and the site of a former herb, spice and perfume (attar) bazaar. Excavations in the depression (magok means “in a pit”) have revealed a shrine to the local moon god, a Zoroastrian temple, a Buddhist monastery and an Arab mosque, stacked on top of each other in layers of history. To the south is the 12th-century mosque portal, stunningly decorated with incised alabaster girikh (geometric designs). A carpet museum occupies the interior, but a portion of the excavations lie revealed in the far corner.

To the west of the Tok-i-Sarrafon is the 16th-century Gaukushan Madrassa, now a metal-chasing workshop and named after the slaughterhouse (gaukushan means “cow-killer”) that used to occupy the site.

Lyab-i-Hauz

With its traditional architecture and ancient mulberry trees set around a central stepped pool, the mahalla (district) of the Lyab-i-Hauz (“Around the Pool”) is in many ways the town’s most attractive. The hauz (pool) dates from 1620 and was one of 200 that supplied Bukhara with its drinking water (as well as many of its infectious diseases). The shady poolside chaikhana (teahouse) is a great place to relax over a bowl of plov and a pot of green tea, though tourism has forced out most of the aksakals who gave the place much of its character.

The hauz was commissioned by Grand Vizier Nadir Divanbegi, who also initiated the khanagha (pilgrim hostel) and mosque to the west. East of the pool, the Divanbegi Madrassa was originally built as a caravanserai, but when the khan mistakenly inaugurated it as a madrassa it had to be hastily converted (once uttered, the edicts of the khan could never be rescinded). Two mythological birds decorate the portal, grasping white doves in their talons. The Mongol-faced sun recalls the Shir Dor Madrassa in Samarkand. The madrassa hosts a colourful nightly folklore and fashion show in summer, and the nearby puppet show is also worth a visit.

Shop

These days most of Bukhara’s bazaars and architectural sites are home to souvenir stalls. One of the best local buys are Bukharan-style miniature paintings, reproductions of court scenes, medieval folk tales and famous vignettes taken from such Central Asian literary classics as Navoi’s Khamsah and Firdausi’s Shahnameh. Visitors can often watch the artists painting new works.

To the south is a statue of Khoja Nasreddin, the Sufic holy fool, whose humorous sayings and anecdotes are much loved throughout the Islamic world. Finishing off the ensemble to the north is the Kukeldash Madrassa (1568), the largest in Central Asia, with 160 student rooms.

The town’s Jewish quarter stretches south from the Lyab-i-Hauz. Legend has it that the Jews were given this land in exchange for the area now known as Lyab-i-Hauz. Bukhara’s Jews trace their arrival in Bukhara from the 14th century and they long played an important role in trade with the Khazaria region in the Russian Volga. The community once numbered 4,000, but since 1991 many have opted for a new life in Israel. It’s possible to visit the nearby synagogue and Jewish cemetery.

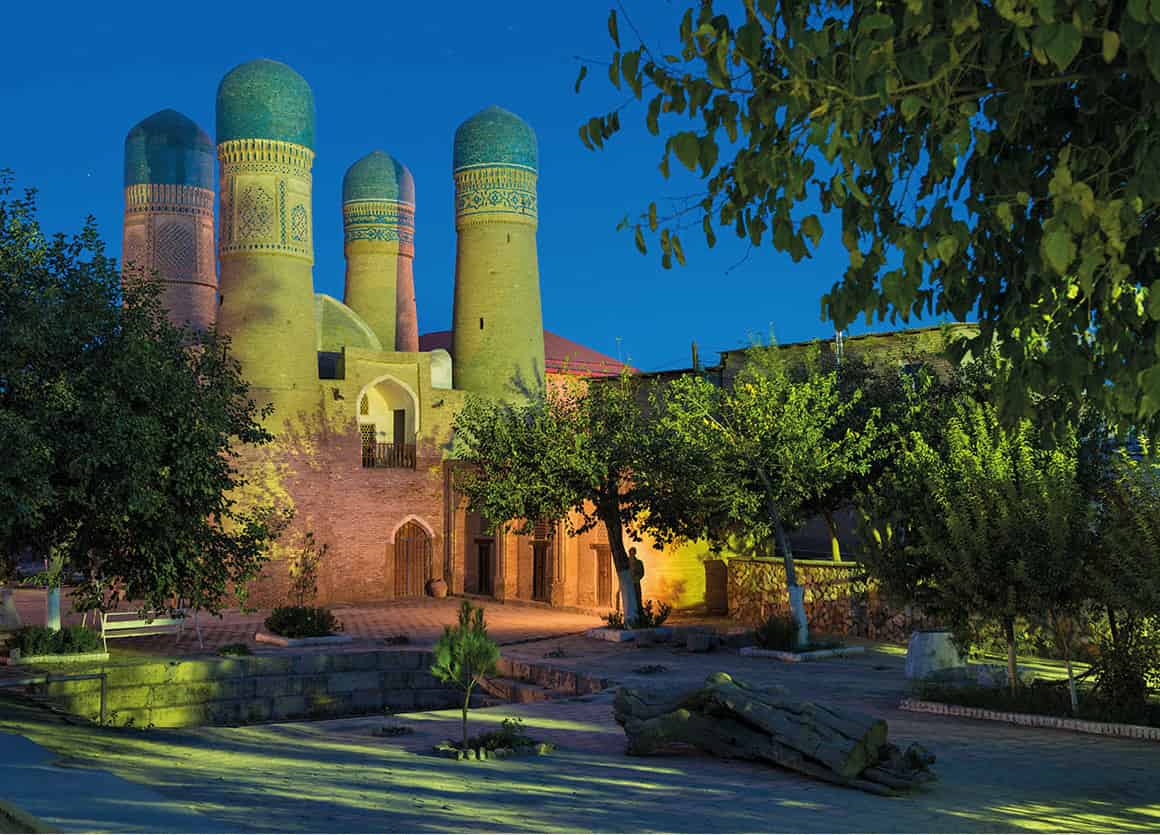

A few hundred metres east of the Lyab-i-Hauz is the Chor Minor (1807), one of Bukhara’s quirkiest buildings. This architectural oddity, which resembles an upside-down chair, is actually the gatehouse of a destroyed madrassa. The blue domes of the eponymous four minarets (chor minor) were once topped by storks’ nests and fell into disrepair but have since been restored by Unesco. A souvenir seller occupies the ground floor and will allow visitors to climb onto the roof (charge).

The Chor Minor once opened into a large madrassa complex. Its name means “The Four Minarets” in Tajik, although its sky-blue turrets have little in common with ordinary minarets.

Getty Images

Suburban Bukhara

If you have a spare few hours, head into the northern suburbs to the Sitorai Makhi Khosa, otherwise known as the Emir’s Summer Palace (Wed–Mon 9am–5pm, Tue until 2.30pm; charge). Built by the Russians in 1911, the kitschy half-European, half-Oriental palace was home to the last emir of Bukhara, Alim Khan, until he fled to Afghanistan in 1920. The first Congress of the Bukharan Soviet was held in the palace that same year, heralding the dramatic political changes to come.

The wedding-cake-like complex leads into an inner courtyard of reception halls, where you’ll find the museums of Applied Arts, National Costume and Needlework. The examples of gold embroidery and suzani (wall hangings) here are particularly fine. The last museum is housed in the former palace harem, where a voyeuristic emir would watch his concubines bathing, before throwing an apple to his passing favourite. The complex is fascinating in its depiction of an emirate straddling the medieval and the modern and was the first place in the Bukharan emirate to have electricity.

Around Bukhara

About 12km (7.5 miles) from Bukhara in Kasri Orifon village is the Bakhauddin Naqshbandi complex, centred around the tomb of the 14th-century saint who is Bukhara’s spiritual protector. With its “wishing trees”, holy stones and sacrificial offerings, the site offers a glimpse into Central Asia’s brand of popular or “parallel” Islam, which has its roots as much in an animist past as in the formal teachings of Islam. Apart from the saint’s tomb, the complex includes two mosques, a huge khanaga (1544) and the tombs of two khans, Abdul Aziz and Abdullah II.

The imposing city walls of Khiva.

Shutterstock

The other main Sufic site is the Chor Bakr, whose street of tombs is centred around the graves of Sayid Abu Bakr and three brothers (chor Bakr means ”four Bakrs”). The term sayid denotes a direct descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, and the sanctity this brought the complex made it the preferred burial place of the Bukharan aristocracy. The quiet complex of mosque, pilgrim accommodation, chillakhanas (meditation rooms) and takharatkhanas (place for ablutions) remains a pilgrimage site and its gardens are a tranquil spot for picnics. It is 6km (3.5 miles) west of Bukhara.

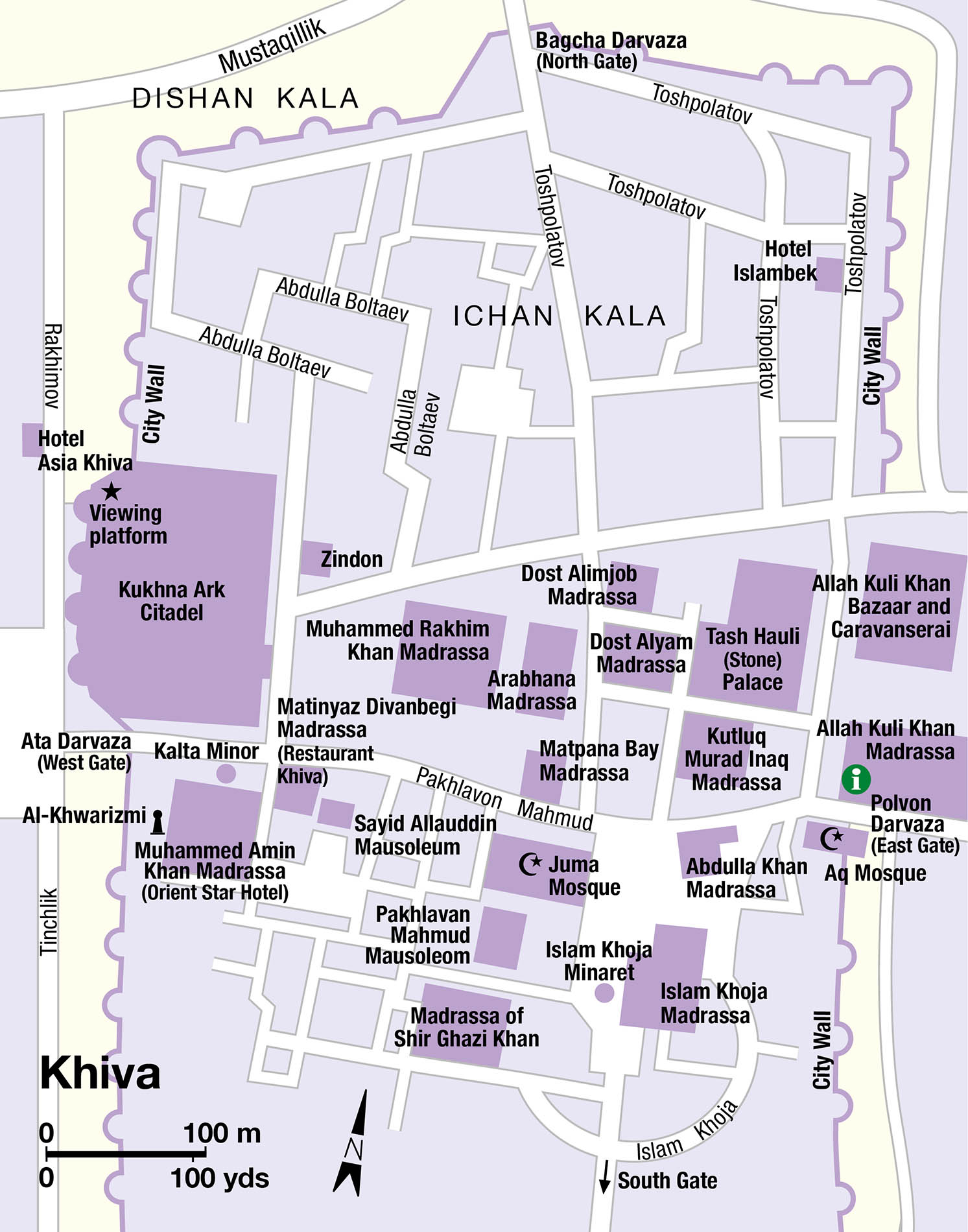

Khiva and Khorezm

Hiddenin the deserts of northwest Uzbekistan, an 18-day journey by camel from Bukhara (or 45-minute flight from Tashkent), the oasis caravan town of Khiva (Xiva in Uzbek) has long been the remotest of the three khanates.

Though local legend has the town founded by Shem, son of Noah, Khiva is not the most ancient town in the region. Like its great brethren the Indus, Nile and Euphrates, the Oxus Delta has long nourished one of Asia’s great centres of antiquity. Most of these ancient cities lie neglected, lost and baking in the desert sands, though the former capital of Gurganj (Konye-Urgench) can still be visited in neighbouring Turkmenistan.

Khiva prospered after both the Mongols and Timur flattened Gurganj, and it eventually became the region’s capital in 1592. The oasis town provided a vital pit stop for caravans headed to Merv. Trade with the Russian Volga, particularly Astrakhan, added to the city’s wealth and filled its caravanserais with samovars, furs, guns, karakul pelts and Turkestani melons. Isolated and lawless, the city also grew rich on plunder and, importantly, the slave trade.

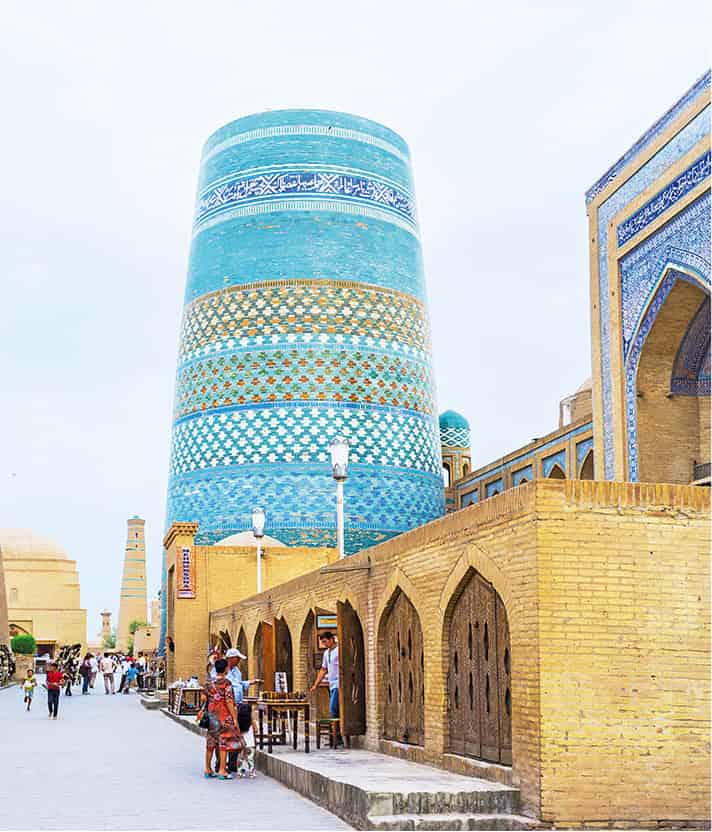

The unfinished Kalta Minor minaret.

iStock

It was the slave trade, specifically the 3,000 or so Slavic slaves, that gave the Russians the excuse they needed to attack its troublesome neighbour. Things did not go well at first. The first expedition ended in the slaughter of 4,000 Russian troops and the despatch of the expedition’s head, literally, back to St Petersburg. The second winter expedition faltered in the frozen desert and never even reached Khiva, with the loss en route of 8,500 camels. In a move typical of the Great Game, the British officers James Abbot and Richmond Shakespear rushed to the city in an attempt to release the slaves and pull the rug from under the Russians’ feet. But it was too little, too late. Khiva was living on borrowed time and by 1873 Kaufmann had engineered the absorption of the khanate into the Russian Empire.

Today Khiva is the most architecturally intact and tightly packed of Uzbekistan’s Silk Road cities. Its intense green-and-blue tilework ranks as some of the most opulent in Central Asia, but it also has the feel of a movie set or a museum city, frozen in time and without the lived-in feel that makes Bukhara so fascinating.

The main points of interest are in the Ichan Kala, or inner city, encased in 17th-century city walls with rounded bastions and punctured by four entrances. These gates were once sealed dusk to dawn to keep marauders out. These days most tourists enter through the western Ata Darvaza gate. The city walls sadly no longer rise from the wind-whipped desert sands but rather from a tarmac car park.

The Ichan Kala

As you enter the inner town, on the right (south) is the Muhammad Amin Khan Madrassa (1855), the largest in the city and named after one of the city’s more impressive khans. The madrassa’s 125 hujra cells, once housing the madrassa’s students, are currently home to the atmospheric Orient Star Hotel. Above the main entrance there is an inscription in Arabic calligraphy that reads: “This wonderful building will stay here forever to descendants’ joy”.

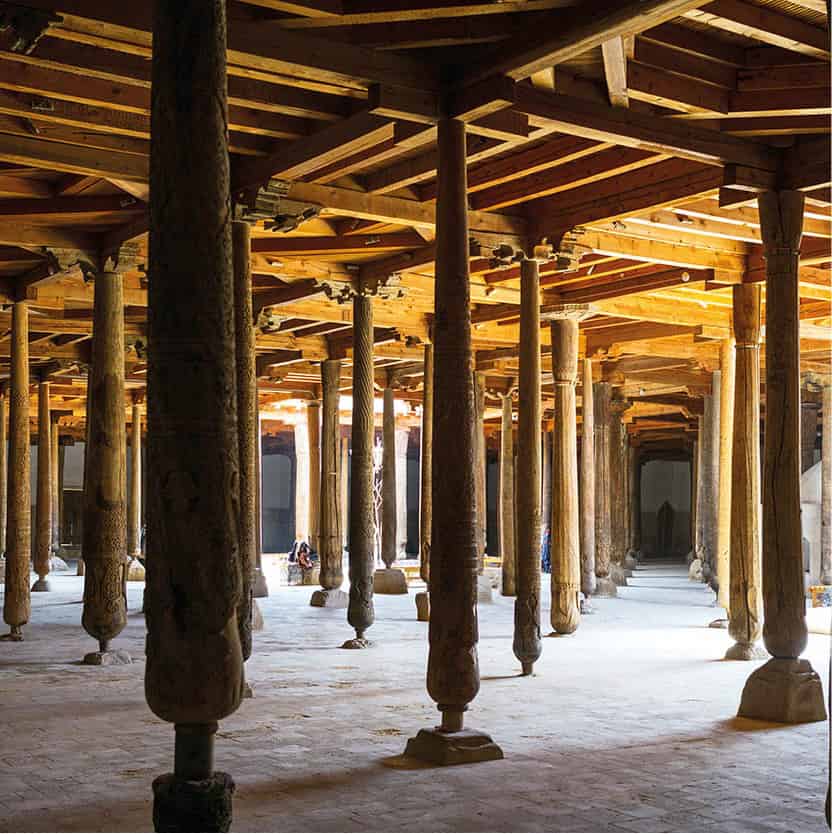

All but one of the columns in the Juma Mosque are carved of black elm wood.

iStock

Beside the madrassa is a glowering statue of al-Khwarizmi (783–840), the brilliant Khorezmian mathematician after whom the word “algorithm” is named (he is also considered the father of algebra – another Arabic word, al-jabr). Khwarizmi was born in Khiva but spent much of his working life in Baghdad.

Outside the madrassa is the bright green stub of the Kalta Minor, commissioned by Amin Khan to be the world’s tallest minaret, but abandoned as too costly after the khan was murdered three years later. It is consequently rather squat in appearance.

To the left is the Kukhna Ark, the oldest core of the original fortress, whose roots stretch back some 1,500 years. The complex is notable for ice-blue tilework and tall iwans that face north to catch the prevailing summer breezes, with great views of the old city from the viewing platform on the roof. The royal rooms include a summer mosque, mint, harem and a throne room where the khan would meet winter guests in a felt yurt erected on a brick base (the yurt was easier to heat than the draughty brick halls of the palace). Just outside the Ark is the zindon, or city jail.

To the east is the Muhammad Rakhim Khan Madrassa (1871), now home to a crafts centre. A museum is dedicated to the khan, who was also known for his poetry, written under the name Feruz Shah. Feruz was the last khan of Khiva. An interesting figure, his notable achievement was to bring the khanate’s first telephone from St Petersburg, with little thought to the fact that there was no telephone line for hundreds of miles in any direction.

Tip

Just inside the West Gate is the Tourist Information Office in Khiva, which can supply a car and driver for trips out to Khorezm. One of the more popular options is a half-day visit to the remote Ayaz Qala and Toprak Qala fortresses. Some hotels also offer other excursion options.

One of Khiva’s holiest sights is the Pakhlavan Mahmud Mausoleum, which commemorates the poet, wrestler and patron saint of Khiva who died here in 1325. The 19th-century tomb contains some of the city’s best tilework and also the largest cupola in Khiva. The Soviets spent years trying to dislodge the cult of Khiva’s local pirs (holy men), but the spot is still madly popular with pilgrims and wedding parties who come here for blessings.

Opposite the tomb is the Madrassa of Shir Ghazi Khan, built with the sweat of 5,000 Persian slaves who, sensing that their promised freedom was not forthcoming, lynched the unfortunate khan inside his new building. The inscription on the portal reads stoically, “I accept death at the hands of slaves.”

Khiva’s tallest minaret, the 45-metre (148-ft) Islam Khoja Minaret, is named after the enlightened early 20th-century grand vizier who built several public schools and hospitals before being assassinated by outraged religious conservatives. Built in 1908, it is the last Islamic monument to be built in the city before the arrival of the Soviets. The attached madrassa hosts the city’s best museum, featuring some wonderful silk clothing amongst the other applied arts.

The walls in the harem courtyard of Tash Hauli Palace are decorated with beautiful Islamic glazed tiles.

Shutterstock

If the heat is getting too much, dive into the deliciously cool gloom of the nearby Juma Mosque (1788), supported by a dense forest of 213 wooden pillars that are cleverly arranged to allow the entire congregation a view of the mihrab (niche pointing the direction to Mecca). Aptly, the mosque holds an exhibition of carved karagacha (elm) wood.

Follow the 60-metre (200-ft) -long tunnel of the eastern Polvon Darvaza gate (built in 1806) into the main bazaar, where you can pick up one of Khorezm’s fantastic hats, brightly coloured ikat fabrics and hand-painted ceramics. Be prepared to haggle hard.

Before you leave the old city, don’t miss the 19th century Tash Hauli Palace (Stone Palace), home to the court of Allah Kuli Khan (1826–42) and a highlight of the city. A secret corridor connects the fabulously decorated inner harem to the reception court (ishrat hauli) and law courts. The intricately carved columns are particularly fine, as are the majolica tiles in the harem’s inner courtyard.

Excursions from Khiva

Several ruined and crumbling fortresses in the deserts of the Khorezm oasis make for a great overnight trip from Khiva or Urgench. En route to the desert, near the town of Beruniy, the road crosses a rickety pontoon bridge to offer an unassuming glimpse of one of Asia’s most historically and geographically important defining points: the Oxus River (Amu Darya). Bled almost dry at this point by the thirsty cotton fields of Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, the sluggish river is today only a faint echo of its former self.

Most popular is the enormous 4th- to 7th-century Ayaz Qala, where you can stay overnight in a traditional nomadic yurt. It’s also possible to make camel trips from here and even swim in the desert at the nearby Ayaz Lake.

Of most archaeological interest is the Kushan-era Toprak Qala, the region’s biggest city until the destruction of irrigation canals left it marooned in the desert sands. The Russian archaeologist Tolstov excavated the palace friezes in 1938, unveiling a blend of Classical Roman and Gandharan styles dating from the 2nd or 3rd century AD, a time when the transcontinental Kushan Empire dominated the entire middle leg of the Silk Road.

The other main excursion is to the white salt-caked former shores of the Aral Sea, where you can visit the iconic beached fishing trawlers rusting in the sand, 150km (90 miles) away from the nearest water. In what is perhaps the greatest environmental disaster of recent times (for more information, click here), the dying sea has lost half its area and 75 percent of its volume within a single generation, bled dry by the Soviet obsession with cotton monoculture. A visit to the ruins of the sea and the rusting skeletons of ships is a sobering reminder of the dangers of environmental recklessness.

Ayaz Qala.

Getty Images

The trip leads first to Nukus, the environmentally blighted capital of Karakalpakstan, where art-lovers should stop at the impressive Igor Savitsky Art Gallery (Mon–Fri 9am–5pm, Sat–Sun 10am–4pm; charge), home to one of the finest collections of Soviet avant-garde art from the 1920s and 1930s. Much of the museum’s collection, which numbers some 90,000 items, as well as detailed biographies of represented artists, is available to view online at www.savitskycollection.org. The Karakalpak State Museum and the Museum of Amet and Aymkhan Shamuratiev, a local artist and writer who came to prominence in the early 20th century, are also worth a brief visit.

Emir Nasrullah, the “Butcher of Bukhara”.

TopFoto

Conolly and Stoddart

Bukhara was the setting for one of the most notorious incidents in the Great Game, when two British agents held prisoner by Nasrullah “The Butcher” met their fate.

The emir of Bukhara from 1826 to 1860 was the highly unstable Nasrullah, fondly known amongst his subjects as “The Butcher”, a nickname he received when he killed 28 of his relatives in a bloodstained scramble to become ruler.

In 1837, a Sandhurst-trained British envoy, Colonel Charles Stoddart, arrived at the gates of the emirate in an attempt to build a political alliance between Britain and Bukhara, and to assure the emir that Britain’s push into Afghanistan would not threaten Bukhara. A soldier rather than a diplomat, he quickly offended the volatile emir with his ignorance of Bukharan protocol by arriving in front of the Ark to salute the emir on horseback, rather than first dismounting. Neither did he bring any gifts or a letter of introduction from Queen Victoria.

Stoddart was taken to the Zindon and thrown into Bukhara’s notorious vermin-filled “Bug Pit”, a 6-metre (20-ft) -deep subterranean dungeon, accessible only by a length of rope, where he was held on and off for the next two years. Nasrullah played with Stoddart like a cat with a mouse, alternately releasing him and then sending him back into the pit, until Stoddart was convinced he was quite mad. At one point the emir’s executioner descended into the pit to behead the British officer on the spot, whereupon the desperate Stoddart converted to Islam in exchange for a modicum of freedom. Amazingly, whilst staying in the police house, he managed to smuggle several letters back to his family in which he put on a brave face, despite the ghastly conditions.

Doomed rescue mission

Then in the winter of 1841 another agent, Arthur Conolly of the Sixth Bengal Light Cavalry, arrived outside the gates of Bukhara on a one-man rescue mission. Conolly was certainly well equipped to accomplish the release. A veteran Central Asian political officer who travelled in disguise under the name Khan Ali, he was the quintessential Great Game player, and is even credited as the first person to coin the phrase.

Conolly was treated cordially at first, but when the British Army was routed in neighbouring Afghanistan it dawned on the unstable emir that he had little to fear from a British reprisal and he once again threw both officers into the pit. The emir was convinced that the men were spies, a suspicion not helped by the British government who had already disowned the two men as “private travellers”.

It became clear to the snubbed emir that Queen Victoria was never going to reply to his earlier personal letter. As part of the celebrations over the defeat of his rival the Khan of Kokand, Conolly and Stoddart were led bound into the Registan Square and forced to dig their own graves. Stoddart was beheaded and Conolly was given one last opportunity to convert to Islam, before he too was killed. It was the 24th of June 1842, and one of the darkest days in the Great Game. Within the museum inside the Ark Citadel are copies of the paintings of both men, the originals of which are held in London’s National Portrait Gallery.