2

Welsing for Colossals in Catfishalonia

A Hypothetical History

I chose Catalonia for multiple reasons. First, for its ten-foot-long monster catfish that took off like wildfire when they were introduced into the Ebro River in the seventies, and secondly, to get a fix on this region in Spain. I was also intrigued by the geographical connection between my family history and this fish. Back during the Inquisition, my ancestors fled Spain and settled in a place now known as Spitz-on-the-Danube, where they became Spitzers. It’s also where a fish known as the “Danube catfish” swam through the Austrian city of Wels, and eventually became known as the wels catfish.

All that aside, these truly massive cats, which are the largest freshwater fish in Europe, have established themselves from the United Kingdom to Uzbekistan, throughout half the EU countries, the Baltics, the Middle East, Russia, and parts of Asia. As an introduced species, this fierce and fugly fish is faring well throughout the world, such that the wels (aka Silurus glanus, European catfish, sheatfish, som, malle, or weller) has become a top predator almost everywhere it’s been introduced as a world-class sport fish.

A freak 280-pounder was recently landed on the Po River in Italy by professional angler Dino Ferrari. Or, as the website BroBible framed it, “Italian Bro Wearing NASCAR Gear Catches Catfish Big Enough to Swallow Ricky Bobby.”1 But the wels, as a species, has definitely thrived more dramatically on the Ebro in Spain. On the upper part there’s a shore-angling industry of fishing with halibut pellets, but on the lower, it’s more from boats. And since the best seafood would be closest to the coast, and since the fishing guide website that attracted me the most featured pictures of a nine-foot-long two-hundred-pounder caught from a craft called Pussy Galore, Fate had basically made its call. So I booked the trip, shot off, met Lea in Barcelona, and not too long after that, we were on the water.

3. Viral image of Dino Ferrari and wels catfish. Courtesy of Dino Ferrari.

Reports of sixteen-foot, man-eating catfish have been circulating in Europe since the Middle Ages. A hand and two rings were found in a wels in 1558, and a Hungarian child was allegedly eaten by one in 1613. The corpse of a seven-year-old was supposedly found in a catfish esophagus in 1754, and there’s a report from Turkey about two teenage girls being devoured by a siluro in 1773. These stories may just be rumors, or it’s been posited that the accused river monsters might’ve recycled some drowning victims. Whatever the case, an 1853 article in Fraser’s Magazine claimed two boys had been eaten by a massive wels. This article, written by an anonymous author, also pumped the hand story up to three rings.2

4. Widely circulated “man-eating” catfish image. Courtesy of Mark Spitzer.

Such accounts are just as unverified as those of alligator gars attacking humans. What we can verify is that wels have been historically recorded at lengths of sixteen feet, and that they might be able to swallow children, but it’s very unlikely that they could actually gulp down adults. There’s a popular internet image of an alleged five-hundred-pound piraiba, an Amazonian cousin of the wels, that choked on a fisherman. What this indicates, if anything, is that a wels would have to be extremely enormous to eat a full-grown person, because that piraiba wasn’t even big enough to get the job fully done. What it all comes down to is that we’d have to have some solid proof (not just hearsay) documenting a pattern of human-consuming behavior to confirm that these fish are actually “man-eating catfish.”

Still, the wels can be aggressive, especially when guarding its brood. In 2008 a German bather was attacked in Lake Waidsee in Berlin and suffered a seventeen-centimeter bite. Authorities estimate the size of this catfish to be not much more than three feet long, so imagine the damage a sixteen-footer could do.

Lately, though, the wels has made prime time in relation to one of the world’s most debated crypto-creatures. Steve Feltham, a “Loch Ness Monster hunter” in Scotland, stated that after searching the legendary lake for twenty-five years, he’d come to the conclusion that Nessie was a misidentified wels. This offhand comment was picked up by Fox News and other entertainment venues that ran deceptive headlines insisting that the Loch Ness Monster was most likely a giant catfish.3 Following that, similar headlines began popping up everywhere, spreading a type of news that isn’t news at all. Unless, that is, tabloid news is news to you.

We pulled up to a chicken processing plant where a pipe full of blood and viscera was pumping out a pukey pink cloud of liquid stank, which was attracting minnows, which were attracting gulls. Tying up to that pipe, our guide threw out a cast net for live bait, which, he explained, wasn’t quite legal on this stretch of the Ebro. He said that “the stupid city government” didn’t encourage fishing for these cats and that live bait had been banned, except for worms, which are live bait. Hence, his conclusion that this law must’ve been up made by a woman. “Because,” he noted, “whoever wrote it just doesn’t understand that big fish eat smaller fish!”

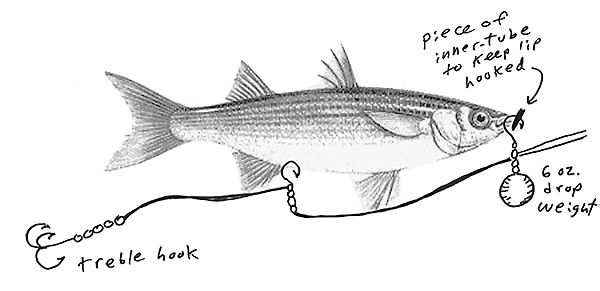

Anyway, he pulled in some silvery three- and four-pound mullets, and we kept our mouths shut because he was the captain. The mullets were then rigged up to our hundred-pound braided lines, which were connected to hundred-pound fluorocarbon leaders, which were tied to steel leaders dangling beneath three giant, fluorescent, ice-cream-cone-shaped floats. Without question, these were the largest baits I’d ever fished with.

In the meantime, the wind was blowing, and this wasn’t helping us. As our guide noted, the wels bite less when there’s wind. He reasoned that waves create sound on the surface, and since these fish are extremely efficient hearers, noise can get in the way of prey. But as he also informed us, the bite usually picks up when the sun starts going down and the day starts cooling off. At that point, the wind lessens, and that’s when his clients tend to get their cats.

5. Mullet rig for wels catfish. Illustration by Mark Spitzer.

It was nice, however, to have a breeze, because the day began baking away. It was 100 degrees in the broasting sun, and the three of us were sweating up a storm as our mullets tooled all over the place. The boat was anchored, and we had to keep switching our two-meter-long catfish poles around so that our floats could pass under the various lines. It was a bit like a shell game, and it took a lot of proactive action to keep from getting tangled.

We fished there for a couple hours, saw a couple huge cat backs breach, then moved upstream to a medieval-modern mashup of a town where ramparts and solar panels competed with steeples and smokestacks to define the skyline. It was a strange amalgamation of the old and the new, which is happening everywhere but not always so visibly.

We began drift-fishing by dragging a drogue, a parachute-looking canvas sack that slows the boat as it’s pushed by the wind. This lessened the need to keep shifting our poles because now we were towing our bait. Nevertheless, the wind kept blowing, and the sun kept roasting with a ruthless desert heat.

By late afternoon I was nodding off, and by five o’clock it hadn’t let up. By six o’clock it was even hotter. Then the wind died down.

That’s when I started taking notes for my “defeat section,” and that’s when the orange float starting acting erratic because something was wigging out our largest mullet. Then that float, it shot off. But then it stopped.

The catfish had dropped the bait, but it was possible that it might circle back. Our guide told me to wait, so I stood poised, ready to hit the lever forward, lock the spool, and set the hook.

Suddenly, the float shot off like a rocket, the guide gave the signal, and I hauled back with brute force. The rod arced. It took less than a second to know that something was on, and it was mongo.

An epic battle then ensued, hauling back and leaning forward, cranking cranking cranking in line. That big old Penn baitcasting reel was bringing in the fish, and the boat was spinning. Lea and the guide were scrambling to reel in the other lines as I horsed and horsed that mother in for about fifteen minutes.

When we saw the orange flash of the float below, I knew a monster was coming up. Its eely form began slashing into sight, and when we saw it, Lea gasped. It was the six-foot wels I’d come to get, and it was on like Donkey Kong!

I got it up next to the boat, and the first thing I noticed was the stunning speckled pattern on its sides. It was a gold-and-black mosaic that reminded me of Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss, a painting that also goes back to my Austrian heritage as well as the house I grew up in, where we had a print on the wall. And now that pattern was flashing on a leviathan that weighed at least a hundred pounds.

But that wasn’t all in the color department because the skin around its pugnacious lower jaw and maw was a brilliant, electric saffron. And when it opened up that mega-mouth to regurgitate a half-digested European eel (and you would too if you’d been hauled up like that), I saw the same vivid coloration in the depths of its gorge.

The treble hook was lodged in one side of its mouth, and there was an injury on the other side: an angry red hamburger mass of shredded-up muscle and meat where it had been hooked before and not that long ago.

Our guide was gloved, and he grabbed the creature’s mouth, which was lined with compact rows of stubby but needly teeth. That catfish’s piehole was large enough to swallow a schnauzer, and it thrashed and got away from the guide. I reeled it back, and he got another grip on it, then hauled it over the rail.

6. Spitzer and Lea with wels. Courtesy of Lea Graham.

That wels weighed 118 pounds, but we didn’t have a tape measure. Still, we compared it to an iron bar on board, which I later used to calculate length. It was six-foot-three, one of the most enormous fish I’d ever caught.

Then we got the money shot, its semi-comic tiny tail flopping over the port rail, its super-wide frogzilla mouth glurping at the sky from the starboard side. Its six long whiskers were dangling down, and it had these teeny-weeny beady eyes that weren’t much larger than BBs staring up from its flattened head. It just sat in my arms with its bulging gut, a gentle giant, who, it seemed, had been in this situation before so knew how to remain composed. Then I released it back to the Ebro, slipping and sliming over the rail, leaving me with an incredibly mucousy layer of goo coating my stomach and pants.

The second day, with Lea gone off hiking to a neighboring town, I didn’t catch squat. Just spent eight torrid hours in the maddening sun. Why no fish hit, I don’t know. That’s the way it goes sometimes.

At night, Lea and I hoofed into the village where we’d gone the evening before. In the town square we’d discovered a friendly bar that made its own wine and offered a selection of local cuisine. Neither of us spoke or read Catalan, but I recognized the word anguilla on the menu, which I remembered from my eel studies. We ordered a plate of that, plus calamari and some sort of oxtail dish. Whereas the eel was exotic in a spicy sauce (small soft bones, cooked with the skin on), the fried squid was exquisite and the best we’d ever had. All we put on it was fresh-squeezed lemon juice.

It was festa time in this ancient place, meaning fireworks and live bands at night as well as loudspeakers pumping out Bruce Springsteen and Michael Jackson. This evening, however, was reserved for the running of the bull—which doesn’t run wild through the streets anymore because things have changed due to a combination of political pressures and animal rights activism. Plus, it’s not uncommon for folks to get maimed or killed when the bulls run. Nowadays, in many towns throughout Spain, the bulls are tethered to a gigantic firehose-looking strap, which is what this bull was strung to. It was controlled by at least twenty shirtless dudes who ran alongside it with hundreds of others: teenage girls, little kids, moms, dads, pastry makers, pretty much half the town.

This was part of an annual ritual that had survived and evolved just like the wels. Whereas the range of this fish had greatly expanded, the size of these cats has radically decreased. Be this due to overfishing or less feeder fish in the systems, I figured that if this trend continues we should count ourselves lucky to experience these fish in such mammoth form when they probably won’t reach such lengths in another few generations.

Because that’s what happens with fish; the more they get fished, the more their overall size diminishes. We can draw an analogy to the white sturgeon, which used to grow to twenty feet. But now, as the Audubon Society asserts, the white sturgeon maxes out at twelve foot six.4 Accordingly, the largest wels on record measured 16.4 feet and weighed over 880 pounds, but these days, it’s rarely half the length it used to reach. If you catch a 200-pounder, or one over 9 feet, that’s about as big as they get.

Whatever the case, the past was apparent everywhere we went in that old stone village, but especially in that snorting bull charging across the cobblestones as we made our way back to the town square. Where, once again, we took advantage of Catalonia’s historic cuisine existing in the modern age. We ate meatballs and garlicky squid, enjoyed tender duck in a glazy sauce, and indulged again in the best damn calamari the universe had to offer.

And as we sat there drinking chilled red wine in the humid night, I couldn’t help romanticizing that as evolution continues to evolve, and as the past endures into the present, and as certain traditions persevere while others naturally die out, the remnants of a family colossus lurk in the murk of history.

The third day, back on the river, which was bordered on both sides by great brakes of cane, Lea came along. The joke was that she’d bring us good luck like she had the first day.

It had rained the night before, which was a good sign. Our guide said that if the river turned a chocolaty brown, then the bite would be on. Since wels catfish rely on their sense of smell and hearing and touch (via whiskers) to detect prey, they have an advantage over fish that rely on sight when the water is muddy.

But since it hadn’t rained that much upstream, the water was as clear as the day before. In fact, it was so clear that you could see labyrinths of Eurasian milfoil growing thick throughout the system. In the United States this plant life is invasive, and state agencies are fighting it like a pox that takes over entire lakes, crowding out all life. But in Europe, Myriophyllum spicatum is a native vegetation that’s not as threatening.

We took off later than usual since we were planning to stay out into the evening, shooting for the windlessness. Motoring upstream, we caught more contraband mullets, then sweltered in the blazing sun.

The hours went by, but it was cooler than the day before, and cooler than the day before that. The wind riffled throughout the afternoon, and we saw plenty of gulls and blue herons, plus another model of a smaller heron with a checkery pattern and a slightly different coloration. The cattle egrets were basically the same as those in the states.

Then, around seven o’clock, just like two days before, that orange float went straight down.

“Strike!” the guide yelled.

I jumped up, locked the lever, and hauled back as hard as I could. Fish on!

“Can you bring in that other float?” I asked Lea, who jumped to the task and started reeling. I wanted to get the other lines out of the way. Not only that, I wanted to give her a crack at this fish. But I knew she’d need the fighting belt to keep the butt of the rod from digging into her pelvis—which I didn’t need because I was wearing a leather belt.

“Can we get the fighting belt out?” I asked our guide, but his response was something I didn’t expect.

“NO!” he shouted, not at me but at Lea. “Leave that float out there! Leave them all out there! Another fish might come along!”

So she left it out as he ordered, and I battled a wels that felt a lot lighter than the one I’d caught two days before. Yet sometimes it would surge, and when that happened, I questioned my assessment.

This one came in a lot quicker. Lea declined to fight it, so I battled it for about five more minutes, and then it was beneath the boat. Predictably, it was tangled in the line that the guide told Lea to leave out. She was shooting video (see “Spitzer vs. Wels Catfish” on YouTube), and he started flipping out.5

“No!” he scolded. “This is not the time for video! Put that down and hand me that pole! We’ve got to get this mess untangled, or we’ll lose the fish!”

Meanwhile, I was fighting a monster cat that was testing everything I had. My pole was bending, and the other line was wrapped around my line right beneath the tip of the rod. This got our guide up on the bow, where he tried to reverse the knotted mess. Lea had to let out line from the other reel and give him some slack to work with so that the other line wouldn’t slice through mine. Basically, our huffing, puffing guide was trying to create a loop to pass an entire fishing pole through, and the fish was giving him guff.

He began shouting orders at me like, “Step back!” and, “Give me some room to operate!” when I was the guy fighting the fish—a procedure we went through several times when he should’ve just cut the other line and hauled the tackle in by hand.

Anyhow, he worked on getting the mess unraveled while I held the fish a foot beneath the boat, where I was trying not to yank it or spook it or make it run in any way. Because if it lurched, the rod could slam down on the rail and break. Even worse, it could lasso one of his fingers and sever it right off.

But then we were free, and I brought it up: a long, dark, even eelier-looking wels. Whereas the first one had been a technicolored neon fatty, this sinewy overgrown sperm of a fish was black and white in coloration. Its tapering anal fin was rippling away, the whole fish looking at least five feet long. But ultimately, after we hauled it in, it turned out to be an inch shy of seven feet and 123 pounds!

It was a male fish, according to our guide, who noted its funny little vestigial dorsal. He also pointed out the pointy shape behind its vent. The females, he said, had a more thumb-shaped flap of skin in that spot.

Again we took a round of pictures, and as we did, our guide pulled its jaws apart so we could get some shots of its throat. Past some of the most impressively menacing, fancy-looking gillworks I had ever seen, you could see four sandpapery crushing pads. Because what these catfish do is they grab their prey with their up-front teeth, then literally Hoover their food straight back, where those pads smash down with hundreds of pounds of pressure and crush stuff to smithereens.

Like the other catfish, we released this one, as is the norm. And the second after it vanished into the Ebro, the silence was totally palpable. It had been a great fish and a bigger fish, but to paraphrase Hunter S. Thompson’s suicide letter . . . football season was over.6

7. The maw of the beast. Photo by Lea Graham.

One thing I should mention is the pool. We had this really cool, above-ground swimming pool—and by “cool” I mean imperative when it’s 100 degrees. It was outside the guest quarters where clients stayed. It was a trailer and it wasn’t that big, but it was comfortable enough. It had two bedrooms, a sitting area, a kitchenette, and a fan.

So Lea and I, we’d come back from fishing, and we’d get a beer, and we’d get in that pool, and that pool made all the difference. In that pool we had quite a few heavy-duty conversations. One went like this:

“It seems there’s some illegality,” she said, “in these fishing trips you take. I’m wondering how you deal with that.”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“Well, when we went piranha fishing in the Amazon, our guide was always looking out for the authorities because it wasn’t legal to fish. But that’s what happens. All the guides were doing that, and all the tourists were doing that. It’s part of the experience. And now, over here, we find that it’s not legal to fish for wels with live bait, but as our guide told us, the other guides do it too. He asked us not to take pictures of the bait, and he asked you not to mention them in what you write. How do you deal with that?”

I’d been thinking about this for a while, and I’d also been researching why live bait was illegal on the Ebro. An email to the Pesca Continental division of the Catalonian government had come back with the reply that live bait was banned “as a method of control and eradication of invasive species.”7 The Google translation was awkward, but it echoed a document I found online published by the Aragon region upstream, which stated, “In order to avoid further spread and invasion of non-native species potentially harmful to aquatic ecosystems and the species that inhabit them, the use as bait of live, dead, parts or derivatives of any specimen of any species of fish, except dead sardines” is prohibited.8 Meaning that because there are now twenty-two invasive fish species in all Catalan river systems as compared to thirty indigenous fish species, the Spanish government wasn’t taking any chances.9 Thus, the situation was akin to a country like the United States banning anyone from coming in, whether they be foreigners or citizens, just to keep out Mexicans.

But back to the original question, which had to do with what I chose to address in relation to what I chose not to mention. “I work with a lot of guides,” I responded, “and they all have certain demeanors. I once worked with a famous guide who called black people ‘crack monkeys,’ and I once worked with another who constantly referred to women as ‘bitches.’ These instances are rare, and more times than not my guides are fine people. But for those who have issues, I suspect it has something to do with knowing fish better than humans—which is why they tend to get the fish for me. And when they do, I don’t complain. That’s what I pay them for, not their anecdotal insights or company. When it comes to writing about fishing, it should be about fishing. Or mostly about fishing.”

I then rambled on about how I’d tried to discipline myself into sticking to the subject matter when tension exists between telling the story as a journalist (which I am, in a way, when I write about fish) and telling the story in a literary way for university presses that don’t wish to raise any hackles. For them, it doesn’t make commercial sense to venture into areas where controversial views can complicate things.

This brought me back to our purposely unidentified catfishing guide, who knew his stuff and produced the fish. But sometimes his anger boiled over. He once snapped at me like he snapped at Lea, and it had been over nothing. I’d been putting mullets into a tub, and he yelled at me because I wasn’t holding the lid over it and he thought some might jump out. But so what if they did? He’d just catch more.

There were a number of other things he’d said that were also disturbing. He’d definitely been critical of some Arabs we saw at the launch one day, and he told me that it’s idiotic to put terrorists on trial when videotapes show them chopping off heads. His thesis was that they should just be executed.

That’s not to say that this guy was all bad. I did have some good conversations with him about gun control and the dilemma of the Confederate flag, in which we seemed to be on the same page. But when a boat got too close to us on the river, or someone was parked on the ramp when we came in, some anger management issues arose.

“Well,” I went on, still trying to address her question, “I try not to get personal, and I sometimes have to censor myself, or what I want to write about. But in this case, I think I need to be honest about the bait we used and how we got it. Not that it’s a big deal, but my loyalty is to history, not him.”

“What do you mean?” Lea asked.

“What I mean is, I need to be faithful to the details that matter, not his business interests. I never agreed to leave anything out.”

But then I got even more abstract, taking the stance: “This is a history. That is, what I’m investigating . . . it’s a history of a fishery, but it’s also a history of a bunch of histories clashing and reacting and searching for balance. Some people love the wels over here, and others claim they’re wrecking the food chain. But it’s not just about catfish anymore because they’re only part of the equation. And like all histories, there’s no way to be completely objective. It’s a hypothetical history.”

This half-baked theory then led to a much more relevant observation, one that’s key to what I kept trying to get at but just kept skirting. And it goes like this:

So Lea and I, we’re sitting in that pool, and we each have our histories, and we’re each checking to see if our histories are compatible, and the subject is how ecosystems change because of change. Because of migration. Because of native species and nonnative species moving around like humans do—due to all the expulsions and migrations and genocides and slaveries and mass-agricultural pressures on the planet, plus all the jobs and wars and politics that just keep getting repeated.

And Lea—radiant, smiling—says, “You know, getting a close look at those fish really gives you a sense of history.”

And she hits the nail right on the head, informing me with certainty that I couldn’t have said it any better.

And this insight, it supplies what I need to end the chapter with finality—even though I still have questions. The main one being: where is all this monster stuff going, and where will it take me next?