ON SATURDAY, 29 October 1580, the noble-born, imperious, and eccentric Tycho Brahe inscribed the title page of one of the most lavish and spectacular books printed in the sixteenth century (plate 6). Peter Apian's Astronomicum Caesareum was truly astronomy for an emperor's eyes. Dedicated to Charles V of Spain, it had won for its author, an astronomy professor at the university in Ingolstadt, the right to appoint poets laureate and to pronounce legitimate children born out of wedlock. A giant folio with brightly hand-colored pages, not only was it a tour de force of scientific printing, but its numerous sets of volvelles—layers of rotating paper disks—could be used to calculate planetary positions and configurations. Tycho later admitted it had cost him twenty florins, which by today's currency would be roughly $4,000.*

The inscribed Astronomicum Caesareum was a princely gift for a gifted visitor, one Paul Wittich, a peripatetic mathematical astronomer from central Europe. Wittich had been on Tycho's island fiefdom of Hven for about six weeks. He had admired Tycho's quadrant and sextant, had examined the clever scales on the instruments that allowed Tycho to read the angle to a minute of arc, and had heard about Tycho's plans to build a new and larger quadrant, to be affixed to a main inner wall of the Uraniborg castle. Wittich had brought along some ingenious mathematical tricks for converting stellar coordinates from one system to another, much admired by Tycho, and he had some stimulating ideas about the technical details of planetary cosmology. Clearly, Tycho greatly appreciated his visit and hoped that Wittich would return. The big book was part of the strategy. "To Paul Wittich of Wratislavia, friend and fellow lover of mathematics," Tycho boldly wrote in Latin.

I pondered the relationship between the well-known Brahe and the somewhat shadowy Wittich as I drove from Cambridge to Oxford one morning in late January 1978.1 was scheduled to give the astronomy colloquium on my latest Copernican research. The Tychonic bubble had burst a few days earlier, and I was still trying to reassemble the pieces. Wittich seemed part of the puzzle. I had found a fascinating set of annotations in a second-edition De revolutionibus in Wroclaw when Jerzy Dobrzycki and I were there in 1974; they included marginalia copied from both the annotated Liege volume and from Kepler's teacher, Michael Maestlin. There were some mathematical problems that used 52° for the latitude, close to that of Landgrave Wilhelm of Hesse's observatory in Kassel. Today Hesse, lying in west-central Germany, is the eighth largest of the sixteen German states, but Wilhelm's powerful father, Philip the Magnanimous, had divided his territory among his four sons, and Count Wilhelm ruled only the northernmost principality, Hesse-Kassel. Wilhelm owes his lasting fame to his research in astronomy, and his observatory was second only to Tycho's. The rolls of astronomers there included Paul Wittich, who seemed an obvious candidate to be the annotator of the Wroclaw book, but my attempts to locate a sample of his handwriting had failed. Still, in my mind's eye, I had assigned the book to Wittich.

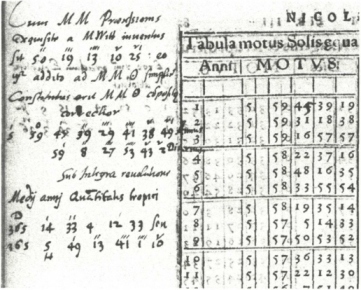

I had found two more samples of what I thought to be the "Tychonic" hand besides those in the quartet of Copernicus books. One was in a rare copy of Tycho's book on the new star of 1572, which I had taken as Tycho's working notes. The other was in that splendid presentation copy of the Apian Astronomicum Caesareum, now preserved at the University of Chicago Library. I supposed that Tycho had made a few marginal notes before magnanimously handing over the inscribed volume to Wittich. Somehow the simple logic that Wittich himself wrote in the book after he got it eluded me on the drive to Oxford.

Tycho Brahe, from Albert Curtz's Historia coelestis (Augsburg, 1666).

My musings turned to two sets of annotations derived from the four pseudo-Tycho De revolutionibus copies, which I had seen in the summer of 1975. Both had been made by Scots working on the Continent and brought back to their homeland. Duncan Liddel of Aberdeen taught some years in Rostock, and in 1587 he paid a week's visit to Tycho's Uraniborg castle. John Craig of Edinburgh had been dean at Frankfurt an der Oder for several years but later returned home and became personal physician to James VI (later to become James I of England). The king had paid a state visit to Uraniborg in 1590, and quite possibly Craig was part of the retinue. Craig's books passed to the king's secretary, who eventually donated them to the Edinburgh University Library.

By now I was in the outskirts of Oxford, and, still puzzled, I forgot about Tycho, Wittich, and the Scots, and concentrated on the traffic. I broke the news to my Oxford audience that Tycho was not, after all, the draftsman of the wonderful diagrams in the Vatican Copernicus.

The next afternoon, as I drove back to Cambridge, all at once I remembered an essential clue. Both Liddel and Craig had been tutored by the mysterious Paul Wittich. And something else clicked. In the Liege copy, the one whose annotations Bob Westman had first noticed, there was a marginal note in the first person: "the mean motion most exquisitely determined by me." Craig's copy in Edinburgh read somewhat differently. It said something about "Witt," which I had taken as an abbreviation for Wittenberg. But what if instead it stood for Wittich? Did the note say that Wittich himself had determined "the mean motion most exquisitely"? I could scarcely wait to examine the microfilms, but it was hard to drive much faster on the winding route from Oxford.

As soon as I got back to Cambridge, I confirmed the reading in Craig's copy. How could I have been so dense not to have noticed it before? I telephoned Bob Westman. "I know who annotated the Vatican copy. It was Paul Wittich." Bob was skeptical but soon came around to the new view. Our task was then clear: to find out everything possible about the elusive Paul Wittich. To begin with, Wittich was born in Wratislavia— today Wroclaw, sometimes Breslau. Changing the attribution from Brahe to Wittich unexpectedly cleared up one puzzle, explaining in a stroke why Copenhagen and Uraniborg weren't in the geographic table in Ottoboniana 1902, and why Wratislavia was.

A rich mine of Wittichian information existed in the Tycho Brahe Opera omnia. Its extensive index enabled us to find that Tycho had frequently mentioned Wittich in his letters. We also discovered, quite critically, that while Wittich had visited Uraniborg, a comet had appeared, and Wittich had recorded his observations in Tycho's logbook. Some years later, after Wittich had died, a countryman visited Tycho (who by then had moved to Prague), and he wrote into the logbook that he recognized Wittich's writing on the page of comet observations. We promptly wrote to Copenhagen for color photographs of those pages of the logbook, and the Royal Library responded with admirable efficiency. If any doubt remained, it was totally dispelled by this new evidence. The handwritings matched beyond a shadow of doubt.

The critical "Master Witt" annotation copied by John Craig into the margin of his De revolutionibus, folio 82 verso, now in the University of Edinburgh Library.

But who was the mysterious Paul Wittich? Because he had never published anything, his reputation had nearly perished. Yet, as we gradually discovered, astronomical correspondence in the sixteenth century was full of him. He was obviously very clever, mathematically gifted, and rich enough to afford at least four copies of Copernicus' book. He never settled down for long in any one place, and though he handed over some of his observations to be published by the royal physician to Emperor Rudolf II, he somehow couldn't bring himself to send any of his mathematical inventions to the printers.

One of his mathematical schemes was particularly ingenious: Wittich found how to replace multiplication and division with addition and subtraction. At first glance this sounds a lot like the invention of logarithms, a discovery attributed to John Napier of Edinburgh around 1614. In fact, Anthony a Wood, one of the great English gossips of the seventeenth century, wrote that Napier had got the idea for logarithms from a method brought back from the Continent by John Craig. In one of his copies of De revolutionibus, Wittich used some empty space at the end of a chapter to pen in a prototype example. He had discovered how to use the rules for sines and cosines of the sums and differences of angles to reduce multiplication of angles to addition. The prototype was rather like using a sledgehammer to crack a walnut, but at least it showed the procedure. And this was precisely one of the pages that John Craig had transcribed into his copy of De revolutionibus when he was being tutored by Wittich in Frankfurt an der Oder in 1576. In turn he took his annotated copy with him when he returned to Edinburgh, and he surely must have shown it to Napier, who was living in a castle in the area. Here was the paper trail to fill in Anthony a Wood's tale.

Early in the twentieth century another astronomer-sleuth, J. L. E. Dreyer, who was then producing the monumental Opera omnia of Tycho Brahe, had become suspicious that his protagonist had appropriated from his visitors these mathematical techniques, which go under the jaw-breaking name of "the prosthaphaeresis method."* He knew that Tycho had boasted of a handy procedure that made it easier to convert his altitude and azimuth measurements into the celestial coordinate system of latitude and longitude. Tycho had only a partial set of techniques until 1598, when he met Melchior Jostel, a mathematics professor in Wittenberg. Dreyer, in his sleuthing through the manuscript repositories in Europe, found that, despite Tycho's claim to have worked out the method with Jostel, the Wittenberg professor actually had the technique himself well before Tycho had arrived.

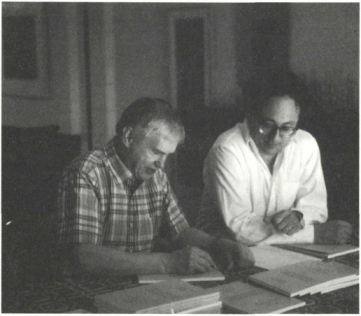

Owen Gingerich and Robert Westman signing presentation copies of The Wittich Connection in the Westmans' La Jolla living room, 1988.

Dreyer, who did not know about Wittich's mathematical examples in his De revolutionibus, nonetheless asked, "Is not the conclusion irresistible, that similarly the invention of the method in 1580 was due to Wittich alone?" Strong evidence exists in Tycho's correspondence that Wittich had carried the De revolutionibus containing his mathematical methods along to Hven on his 1580 visit. A decade later, when Tycho learned that Wittich had returned to his hometown of Wroclaw and had died there, he began a campaign to buy Wittich's library. In one letter he specifically asked for the three copies of De revolutionibus (apparently the number Wittich had brought along with him) containing the cosmological diagrams and the mathematical notes. And eventually he succeeded in buying them. So when a Jesuit librarian wrote in the Prague copy, "known to be Tycho's," he was indeed correct; the notes themselves, however, belonged to Wittich, the previous owner.

As Westman and I pored over Tycho's correspondence (published in the Dreyer Opera omnia), the details of the Wittich story gradually emerged. Further information on Wittich's peregrinations turned up in the correspondence of Andrew Dudith, a sixteenth-century Hungarian churchman, statesman, and devoted amateur astronomer; his original letters had disappeared during World War II, but a Czech scholar had photographed them before the war, and we managed to get a set of prints from an astronomical historian in Prague.

We made no secret of our new identification of the Prague/Vatican/ Liege annotations. Since we were bound by our agreement to publish the fruits of our researches jointly, nothing yet appeared in print, and the project was clearly too intricate for us to complete while we were still together in England. Nevertheless, I lectured rather widely on "The Mystery of Master Witt," which included the curious prehistory of logarithms. Therefore it was quite a surprise, shortly after my return to the United States, to be asked by Sky and Telescope magazine for an illustration from the Vatican copy of De revolutionibus to be used by Edward Rosen in an article entitled "Render Not unto Tycho That Which Is Not Brahe's."

For many years Rosen had had the field of Copernican studies virtually to himself, but with the Quinquecentennial he faced increasing competition. While he could be a delightful social companion, he was at heart a very scrappy New Yorker. He was also highly secretive, being plagued with fear that his researches would be plagiarized; as a consequence, he seldom shared what he was currently investigating, nor did he communicate with his colleagues to find out what they were doing. So he was in the dark about our new attribution of the pseudo-Tychonic materials. He had independently noticed that the handwriting in the Vatican Copernicus could not possibly have been Tycho's, but he had no idea who the actual annotator was.

I immediately wrote to Ed, explaining that we had known for some time that Tycho hadn't annotated the Vatican Copernicus, and that in fact, we knew the annotator was Paul Wittich, though I didn't mention our specific evidence. Rosen was outraged, as we found out afterward, because, not knowing the correct identity of the Vatican annotator, he had put into print a mistaken attribution. A stickler for accuracy, he had erred in a dozen notes in the edition of his translation of De revolutionibus, which had meanwhile appeared in the Polish Complete Works series—endnotes that attributed various readings to Brahe instead of Wittich.

Aware that Rosen was on the same trail, Westman and I rushed a note to the Journal for the History of Astronomy outlining the evidence for the change in attribution. But Rosen marched on as if he had been the first to assemble the evidence about Wittich and, ignoring our note, published a long article in which, among other things, he analyzed in some detail how previous biographers of Paul Wittich had gotten his death date wrong. Since we had already been onto the relevant manuscript material, we saw at once, to our amazement, that he had misread the writing. He had corrected the year appropriately but had mistaken the day, reading an abbreviation of the "5th of the Ides of January" for the "5th day of January." It was of course totally inconsequential whether Wittich had died on 5 January 1586 or on 9 January 1586, but we knew that Rosen took such minutiae very seriously indeed. We ultimately scored a trivial point in our minor game of one-upsmanship, and Ed Rosen silently corrected his error in one of his later publications.

Of more substantial importance than finding the day on which Wittich died was deducing the year in which he was born. Tycho had always implied that it was "young Wittich" who had visited him, but that could simply have resulted from his highborn arrogance. With his snobbish manners, nearly everyone seemed in some way inferior. The key to calibrating Wittich's age fell into my hands entirely serendipitously several years later, fortunately before we published our definitive account of the Wittich connection.

The library of Duke August in Wolfenbiittel was considered one of the greatest, if not the greatest in seventeenth-century Europe. Today Wolfenbiittel is just a small town east of Hannover, but it is still renowned for hosting one of the premier research libraries in Germany. Isaac Newton's rival, the polymath Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, was for some years its librarian. Among its many impressive treasures are two first editions of De revolutionibus, which I had examined in 1973 and again in 1978, but it was not just Copernicus' book that I was looking at in the spring of 1986.1 was systematically examining all of their astronomy books, thinking about the possibility of a special exhibition. Among the curious volumes I opened was a printed astrology text with a set of extra pages on which the owner had constructed birth horoscopes for his classmates at Wittenberg. I quickly realized that the book had an interesting research potential. With all those birthdays I could find out how old the students at Wittenberg were. In the late Middle Ages young teenagers went to the university, but were thirteen-year-olds typically at Wittenberg in the age of Copernicus? Miriam joined me in the library and set to work with the printed matriculation list for Wittenberg University, matching names with the manuscript horoscopes. The average age of entry turned out to be seventeen, much the same as in today's universities.

Our result, published in the journal History of Universities, intrigued the editors so much that they included an editorial that was even longer than our article. They considered our findings to be a breakthrough in understanding the nature of the European undergraduate population in the 1500s. And our result provided the basis for deducing when Wittich was born, since we knew he enrolled at Leipzig in the summer of 1563. If he was seventeen, then his birth year was around 1546, making him the same age as Tycho. But Tycho, precocious lad that he was, had turned up at Leipzig at age fifteen. He later recalled having been at Wittenberg the same time that Wittich was there, but that he scarcely remembered him. Tycho may not have recalled that meeting very well, but his memories of Wittich's visit to Uraniborg and its aftermath were all too clear.

Paul Wittich was a cut above most of the helpers who had arrived on the island of Hven. He was more akin to Tycho both intellectually and socially. The imperious Tycho needed appreciation, and Wittich could offer it as he admired the instruments on the balconies of the Uraniborg castle. So Tycho held nothing back as he explained the novel star-sights and scales on his quadrants, sextants, and armillary spheres. They toured the library with its thousands of books and its giant celestial globe, and they swapped notes on their ingenious trigonometrical methods. And the guest showed his host the technical underpinnings of his cosmological speculations, elegantly drafted into the copies of De revolutionibus that accompanied his wanderings. The idea of preserving some of the Copernican details, but with the Earth at the fixed center, must have greatly intrigued Tycho. He may have already been thinking along those lines, but seeing the specific arrangement of the planetary mechanisms within a geocentric framework must surely have spurred his own imagination. Clearly, Wittich's copies of De revolutionibus impressed Tycho, for he spent a decade pursuing those books, specifically mentioning their number and their contents, before he finally got them.

Despite his brilliance, Wittich seems to have been much more laid-back than Tycho. I have known a number of scientists, more than competent, wonderfully helpful and full of ideas, who could scarcely ever bring themselves to turn their researches into a publishable paper. Wittich must have been one of this type, for there is a not a single published book or paper with his name on it. No doubt on Hven he became increasingly wary of the arrogant, high-intensity Tycho, and when an inheritance came his way in Wroclaw, he used it as an excuse to escape the snare. He obviously accepted the huge Apianus volume, and he promised to come back, but he never did.

The next Tycho heard of Wittich was that the Wratislavian was holding forth at the observatory of his chief astronomical rival, Landgrave Wilhelm of Hesse in Kassel, revealing the secrets of Tycho's star-sights and scale graduations and much else. Tycho was infuriated and felt badly burned. Never again would he be so open about his inventions. He became a changed man, secretive to the point of paranoia. And he soon had occasion to be truly paranoid. This time it was not the upper-class Wittich, but a lowborn autodidact, once a swineherd, who became the thorn in his side.

* Copies today sell in the vicinity of half a million dollars.

* Coming from the Greek, prosthaphaeresis literally means "addito-subtractive."