GEORG JOACHIM RHETICUS needed many months to persuade Copernicus to send his book to the printer. The Polish astronomer's reluctance to publish his manuscript must have arisen from a complicated jumble of reasons and phobias. In the first place, there was no suitable printer nearby to handle a complex technical work, and besides, there were still many details not quite polished to his satisfaction. But lurking in the background was the fear that his ideas about the mobility of the Earth, so contrary to common sense, would lead to his being hissed off the stage. That is precisely how he expressed it in the dedication that he eventually wrote to Pope Paul III.* And he knew that he might be in trouble with some religious sensitivities. Though he explicitly dismissed this in his dedication to the pope, saying, "Perchance there will be babblers who take it on themselves to pronounce judgment, although completely ignorant of mathematics, and by shamelessly distorting the sense of some passage in the Holy Writ to suit their purpose, will dare to find fault and censure my work, but I shall scorn their attack as unfounded," he must have worried about their potential criticism.

Foremost among the biblical verses that could cause trouble was a vivid passage from the Book of Joshua.

On that day when the Lord delivered the Amorites into the hands of Israel, Joshua spoke with the Lord, and he said in the presence of Israel:

"Stand still, 0 Sun, over Gibeon

and Moon, you also, over the Valley of Aijalon."

And the Sun stood still and the Moon halted,

till the people had vengeance on their enemies.

Is this not written in The Book of the Just? The Sun stood still in the middle of the sky and delayed its setting for almost a whole day. There was never a day like that, before or since.

In Wittenberg, even before De revolutionibus was printed, Martin Luther had cited the Joshua passage in the course of a dinner conversation. Apparently, Luther had heard about the new cosmology from Rheticus or Reinhold at the university. Despite the informality of the mealtime setting, an eager student named Anton Lauterbach copied down the critique: "There was mention of a certain new astrologer who wanted to prove that the Earth moves and not the sky, the Sun and the Moon. This would be as if somebody were riding on a cart or in a ship and imagined that he was standing still while the Earth and trees were moving. Luther remarked, 'So it goes now. Whoever wants to be clever . . . must do something of his own. This is what that fellow does who wishes to turn the whole of astronomy upside down. . . . I believe the Holy Scriptures, for Joshua commanded the Sun to stand still, and not the Earth."

Or maybe that's not exactly what he said, because another student, Johannes Aurifaber, later reported it a little differently. "That fool would upset the whole art of astronomy," Luther supposedly said, in what is one of his most widely quoted lines, though the experts generally believe this version is apocryphal if for no other reason than that Aurifaber wasn't actually present at the dinner.

These off-the-cuff remarks might have been forgotten, though they were printed along with numerous other of Luther's conversational views in the Tischreden, or "Table Talk," series, first published in Wittenberg in 1566, long after Luther's death. But his opinion was given a popular press when Andrew Dickson White, the first president of Cornell University, publicized the reformer's Copernican remarks in 1896 as part of his A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom. A liberal Christian, White announced that his goal was to let "the light of historical truth into that decaying mass of outworn thought which attaches the modern world to medieval conceptions of Christianity—a most serious barrier to religion and morals." He was eager to discredit what he believed was religion's antipathy toward the march of science, so he got his graduate students to dig up as many cases as they could find. The so-called Galileo affair played a central role in his account, introduced by the following wholly fictitious episode.

Herein was fulfilled one of the most touching of prophecies. Years before, the opponents of Copernicus had said to him, "If your doctrines were true, Venus would show phases like the moon." Copernicus answered: "You are right; I know not what to say; but God is good, and will in time find an answer to this objection." The God-given answer came when, in 1611, the rude telescope of Galileo showed the phases of Venus.

It is true that Galileo's telescope revealed for the first time that Venus went around the Sun, contrary to the Ptolemaic arrangement, but neither Copernicus nor his opponents ever considered such a test. The seeds for this myth were planted, perhaps inadvertently, by the English astronomer John Keill in a Latin textbook he published in 1718. With each retelling the story was more richly embroidered, reaching its apotheosis with White's well-embellished vignette.

In any event, since the infamous Galileo affair played out in a Catholic setting, White was eager to give Protestants a role, too, in religion's presumed resistance to the advances in scientific knowledge. This is why he dusted off a version of Luther's comment. But the former Cornell president was not about to stop with Luther. Despite the fact that Copernicus' book was essentially published under Lutheran auspices, as was the first volume of tables based on De revolutionibus, White continued, "While Lutheranism was thus condemning the theory of the earth's movement, other branches of the Protestant Church did not remain behind. John Calvin took the lead, in his Commentary of Genesis, by condemning all who asserted that the earth is not at the centre of the universe. He clinched the matter by the usual reference to the first verse of the ninety-third Psalm,* and asked, 'Who will venture to place the authority of Copernicus above that of the Holy Spirit?'"

No doubt White's quotation from Calvin increased the readership of Calvin's works, for it set historians of science off on a frustrated search to find where the Genevan reformer mentioned Copernicus. In 1960 Edward Rosen, a master of minutiae, not only tracked down a flock of authors who simply parroted White's account, but traced the comment itself back to the Reverend F. W Farrar, an Anglican canon who was at one time chaplain to Queen Victoria and who overconfidently relied on his capacious memory of quotations to generate out of whole cloth Calvin's comment on Psalm 93. In a sweeping generalization Rosen concluded that Calvin had never heard of Copernicus and therefore had no attitude toward him.†

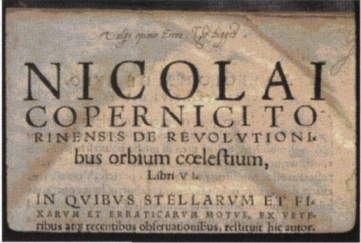

Given the relatively wide distribution of De revolutionibus, I think it highly likely that John Calvin saw the book, but he probably assumed from the notice on the back of its title page, addressed "To the Readers Concerning the Hypotheses in this Book," that Copernicus' book was intended as a mathematical device for calculation and not a real description of nature. This Ad lectorem declared that "it is the duty of an astronomer to record the motion of the heavens with diligent and skillful observations, and then he has to propose their causes or, rather, hypotheses, since he cannot hope to attain the true reasons. . . . Our author has done both of these very well, for these hypotheses need not be true nor even probable; it is sufficient if the calculations agree with the observations." It was added by Andreas Osiander, the learned theologian-minister of the Sankt Lorentz Kirche in Nuremberg who proofread most of its pages. When Copernicus' friend Bishop Tiedemann Giese saw this unauthorized addition, he was greatly exercised and wrote a letter to the Nuremberg City Council demanding that the front matter be revised and reprinted. To Copernicus' first and only disciple, Georg Joachim Rheticus, he expressed the wish that in the copies not yet sold, there should be inserted the little treatise "by which you have skillfully defended the idea that the motion of the Earth is not contrary to the Holy Scriptures." Such a replacement would have been relatively easy at a time when books were sold unbound, as loose stacks of folded signatures.

Because of Bishop Giese's letter, Copernican scholars had long known that Rheticus, in addition to writing the Narratio prima, or "First Report," that served as a trial balloon for the radical heliocentric cosmology, had also written another tract discussing how to understand those scriptural citations that seemed at odds with a moving Earth. But none of his contemporaries, nor, for that matter, Andrew Dickson White and his students, ever knew what Rheticus, a staunch Lutheran, had written on heliocentrism and Holy Scripture. For many years it was assumed that Rheticus' report had been lost in the dustbin of history. Then, almost miraculously, it was rediscovered in the flurry of Copernican researches associated with the 1973 quinquecentennial year.

It turned out that Rheticus' reconciliation of Copernicus' science and Scripture had actually been printed, but anonymously, in a little booklet published in Utrecht in 1651. This long-overlooked tract, now apparently existing in only two copies,* was identified and described by the Dutch historian of science Reijer Hooykaas. Thus we now know that Rheticus quoted Augustine as saying that Scripture borrows a style of discourse from popular usage "so that it may also fully accommodate itself to the people's understanding and not conform to the wisdom of this world." Rheticus emphasized this point repeatedly. He cited a series of passages commonly used to condemn the reality of the heliocentric plan, including Joshua and the battle of Gibeon, and noted that things appear to move either because of the motion of the object itself, or because of the movement of one's vision, but that common speech mostly follows the judgment of the senses, that is, the appearance that the motion is in the object itself. "As persons who seek the truth about things," he wrote, "we distinguish in our minds between appearance and reality."

Yet, decades later, the same scriptural passages were still being used in their literal sense. And, long before Rheticus' little tract was printed (over a century after it was written), his arguments had been independently discovered and advocated by two of the leading Copernicans, Kepler and Galileo. Both Kepler's and Galileo's copies of De revolutionibus survive, preserved in European libraries, and in both cases their annotations tell part of the story of the religious reception of this epoch-making book.

I FIRST SAW, and photographed, Kepler's copy in the Leipzig University Library in the summer of 1972, a year before the quinquecentennial celebrations. In those days one needed a sponsor to enter East Germany, and Miriam and I found one in the publisher Edition Leipzig. It provided the entree into that fenced-off police state and enabled me to see rare books in several libraries. But the most memorable, and spookiest, part came as we were driving out of the country. We had easily cleared the potentially troublesome East German customs—worrisome because I was carrying out undeveloped film—but the young officer had been more interested in practicing English than in searching our luggage. As darkness fell, a large truck blocked the view of the actual exit, and we unwittingly headed off onto a stretch of abandoned Autobahn that meandered through the no-man's-land between East and West Germany. Some distance along this dim and suspiciously untrafficked route we realized that grass was growing down the middle of the highway. In stark terror we did a U-turn, hoping no border guards were taking aim at us. Nowadays it's hard to recapture the sense of relief that always came during those cold war times when one finally transited back into the free world.

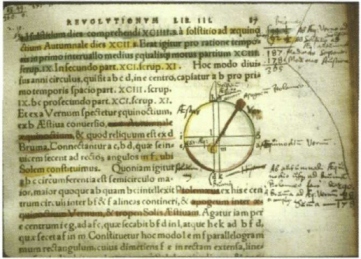

And so I carried out the latent images of Kepler's De revolutionibus. Some of the most distinctive features in the book are not the notes he wrote in it but what was already present when he acquired it. The copy had originally been given by the Nuremberg printer Petreius to a local scholar, one Jerome Schreiber. Schreiber was clearly an insider, and he learned who had written the anonymous Ad lectorem, the advice to the readers printed on the back of Copernicus' title page. One of the slides I made in Leipzig shows the name Osiander written by Schreiber above the Ad lectorem. That annotation tipped off Kepler to the unnamed author's identity.

Kepler was particularly incensed by this anonymous introduction, because, unlike the great majority of sixteenth-century astronomers, he was a realist, and he believed that Copernicus, too, thought that the heliocentric system was a real description of the planetary system and not just a mathematical computing device. Hence he was pleased with himself when he could put his own advice to the reader on the back of the title page of his great Astronomia nova, which was published in 1609 and in which he presented the evidence that the orbit of Mars was not a perfect circle but an ellipse. With the notice on the back of his own title page, Kepler revealed in print for the first time that Osiander had authored the Ad lectorem. He made it clear that Copernicus would not have subscribed to it. Osiander's advice was that the cosmology in the book was merely hypothetical, that "perhaps a philosopher will seek after truth but an astronomer will just take what is simplest, and neither will know anything certain unless it has been divinely revealed to him." Because this advice had essentially protected the book from religious condemnation for many decades, Kepler's revelation that Copernicus had not written nor subscribed to that caveat was dynamite; it undermined the Church's position that heliocentrism was a strictly hypothetical scheme, useful for mathematicians but not to be confused with physical reality. Thus the littie notice behind the title page of the Astronomia nova helped set the stage for the prohibition that would soon follow.

I first saw Galileo's copy, a second edition in the National Library in Florence, in July 1974.1 found myself disbelieving that the book had really belonged to the Italian astronomer, for this copy had no technical marginalia, in fact, no penned evidence that Galileo had actually read any substantial part of it. Yet, as I finally convinced myself, his handwriting was there. He had carefully censored the book according to the instructions issued from Rome in 1620—universal instructions that he had helped trigger.

Galileo's censored Copernicus was just one highlight of an intense weeklong research expedition in north-central Italy. Another memorable moment came in Padua, where the local archives agreed to let me photograph the oldest dated autograph document in Copernicus' own hand. I had brought along my case of photoflood lamps and found a precarious place near an electrical outlet where I could both clamp the lamps and place the open book of documents.* Copernicus, while a medical student in Padua in 1503, had written out a statement to be notarized, and that was the manuscript I photographed.

Copernicus' earliest dated signature, 10 January 1503, from the Padua State Archives.

In twentieth-century Central Europe, bitter contention broke out concerning Copernicus' ethnic origins, which became particularly shrill during the Nazi period. The Germans argued that the astronomer's family name was a Germanic Coppernigk or Koppernig, whereas the Poles defended Copernik. On the Padua document his signature clearly reads Nicolaus Copernik, though he was rather indifferent about orthography and later would occasionally sign off as Coppernicus.†

Besides more than a dozen Copernicus volumes recorded on the Italian field trip, Miriam and I listened to sonorous Armenian chorales in the mosaic-laden cathedral in Ravenna, saw Coppelia danced by the La Scala ballet company in Milan, and feasted our eyes on the Botticellis, Fra An-gelicos, and Michelangelos in Florence and the Giottos in Padua. And while we were in Padua I also photographed the Renaissance anatomical theater, one of only two original surviving examples, the other being in Uppsala. Here medical students in Copernicus' day—and probably Copernicus himself—crowded into the ranks of the small oval auditorium to observe human dissections. Typically, a barber-surgeon would do the cutting while the professor read the relevant text from Galen. Quite possibly, the Italian penchant for cutting up saints to serve as holy relics helped make the medical dissections socially acceptable. We got the flavor of this when we visited the library in Ferrara (which had a censored copy of De revolutionibus) and were there astonished to discover Ludovico Ariosto's heart in a large urn,‡ and we found Galileo's index finger in a reliquary in the Florence History of Science Museum (whose De revolutionibus was not censored).

Although Galileo made his most significant astronomical discoveries in Padua—the mountains on the Moon, the myriad stars composing the Milky Way, the satellites of Jupiter—his years of fame and confrontation with the Church took place in Florence. Like Kepler, Galileo endorsed a realist stance, and to this end he wrote a privately circulated letter in which he argued (as Rheticus had done, though he didn't know this) that the Bible spoke in idiomatic terms so that everyone could understand it, but it was not a scientific textbook. His punch line was that "the Bible teaches how to go to heaven, not how the heavens go." It was one thing for Kepler, who had been trained as a Lutheran theologian, to argue this way in a Lutheran context in the introduction to his Astronomia nova, but quite another for Galileo, who was at best an amateur theologian, to argue the same way in a Catholic context.

In 1545 Pope Paul III had convened the Council of Trent to discuss both Church reform and a hardened line against heretics, and following Pope Pius IV's publication of the council's decrees in 1564, the Protestant protest was no longer seen as an in-house debate. Catholic scriptural interpretation was reserved for the trained hierarchy, and Rome did not like the idea of an amateur theologian rocking the boat when they had their hands full with the heretical dissidents north of the Alps. If Galileo was invading its interpretive turf, the Vatican determined to remind everyone just who had authority by banning Copernicus' book. But it was not that easy. The Vatican claimed the power to establish the calendar, as it had done with the Gregorian reform in 1582. A fundamental part of calendar reform was specifying how to determine Easter, and this required astronomical knowledge of the Sun and Moon. De revolutionibus included observations of the Sun and Moon, of potential value to the Church, so it was inadvisable to ban the book outright. Nor could the heliocentrism simply be excised, for it was too firmly embedded in the text. The only path was to change a few places to make it patently obvious that the book was to be considered strictly hypothetical.

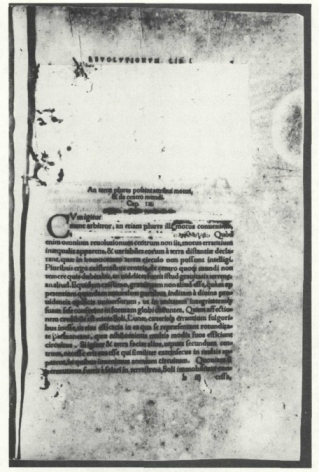

Thus it happened that in 1616 De revolutionibus was placed on the Roman Index of Prohibited Books "until corrected," and in 1620 ten specific corrections were announced. Two examples will show what the Vatican was up to. The heading of Book I, chapter 11, "The Explication of the Three-Fold Motion of the Earth," was changed to "The Hypothesis of the Three-Fold Motion of the Earth and Its Explication." At the end of the preceding chapter, where Copernicus had declared that the great extent of the starry universe made it impossible to detect any annual oscillation in the positions of the stars owing to the Earth's annual motion, he had exclaimed, "So vast, without any question, is the divine handiwork of the Almighty Creator!" This, too, met with the censors' condemnation. Why was such a pious statement forbidden by Rome? Simply because it made it appear that God had created the universe from a heliocentric perspective. All of these corrections were dutifully recorded by Galileo in his copy of the book, though he took care to cross out the original text only lightly so that he could still read it.

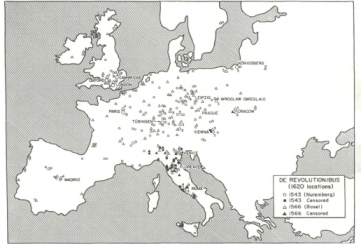

Because the Vatican Congregation of the Index was so explicit about its instructions, it is almost immediately obvious whether or a not a copy was censored, something I took note of as I examined and reexamined several hundred copies of the book. In addition, I systematically recorded provenances, that is, where the books had been. For about half of the copies it was possible to determine where they had been in 1620 when the instructions for censoring the book were announced. Then a very interesting result emerged, something the Inquisitors never knew. Roughly two-thirds of the copies in Italy were censored, but virtually none in other countries, including Catholic lands such as Spain and France. It became apparent that the rest of the world looked on the exercise as a local Italian imbroglio, and they were having none of it. In fact, the Spanish version of the Index explic-idy permitted the book!

The Inquisition's censorship of De revolutionibus, in Galileo's hand in his personal copy.

Copernicus' De revolutionibus, and two later additions, Kepler's Epitome of Copernican Astronomy and Galileo's Dialogue on the Two Chief World Systems, remained on the Index until this became something of a scandal. Not until 1835 did a copy of the Roman Index appear without these titles.*

FOR TWO YEARS during the 1980s I hosted a student from mainland China at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Shida Weng was a victim of China's cultural revolution, consigned to the backwaters when he might profitably have been in graduate school, but he had spent the time teaching himself English. In 1982 the Chinese government sent him to Cambridge to study the history of astronomy. During his stay I took Shida as my guest to the History of Science Society meeting in Norwalk, the one where Bob Westman and I presented our results on Wittich's annotated copies of Copernicus' book. En route I asked Shida what had been his most surprising impression of the United States. He replied that in America we have so many choices, what to wear, what to eat, what to read—a perceptive analysis, I thought. I told him that I hoped to visit his country someday.

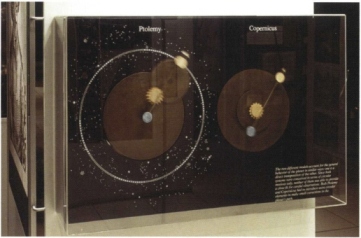

1a. The "Eames machine" in the IBM Copernican exhibit demonstrated the equivalence between the Ptolemaic epicyclic model (left) and the Copernican orbits for Mars—the rods remained parallel as the circles rotated in each system.

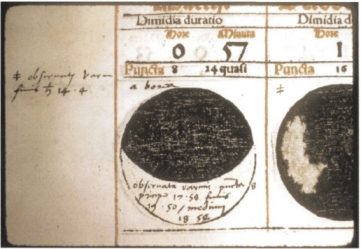

1b. Copernicus' eclipse annotations in his copy of johann Stoeffler's Calendarium Romanum magnum.

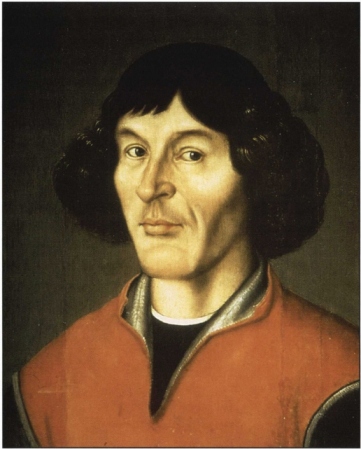

2. Tobias Stimmer's portrait of Copernicus, part of the decoration of the great astronomical clock in the Strasbourg Cathedral.

3. Nicolaus Copernicus, Torun town hall, presumably based on the self-portrait mentioned by Stimmer (see facing page).

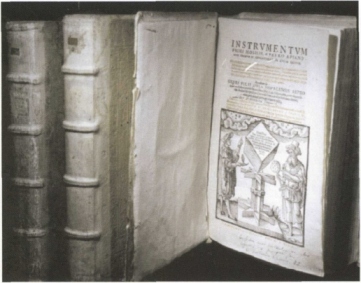

4a. The three volumes given to Copernicus, with Rheticus'presentation inscription.

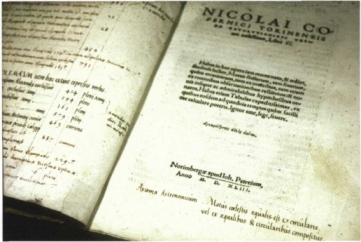

4b. Erasmus Reinhold's summary on the title page of his richly annotated De revolutionibus.

5a. The Copernican Library preserved at Vppsala University. Copernicus' copy of the Regiomontanus Epitome of the Almagest has not been located, and another copy (foreground) was substitued for the picture.

5b. Charles Eames photographing the Copernican books in the Vppsala University Library.

6. Peter Apian s Astronomicum Caesareum with Tycho Brahe's presentation inscription to Paul Wittich.

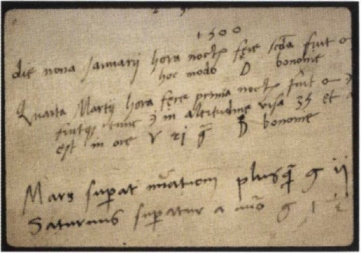

7a. Copernicus'brief observational notes in the so-called "Vppsala notebook "

74. Thomas Digges's signed endorsement of Copernicus: "The common opinion errs."

7c. Herwart yon Hohenburg's colorful annotations in his De revolutionibus.

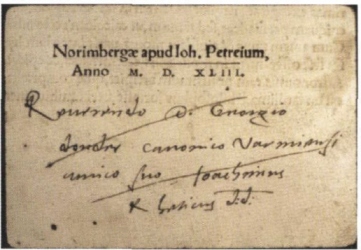

7d. Rheticus'' dedication inscription to the Varmian canon George Donner.

7e. Wilhelm Schickard y s artistic talents are evident in his marginal drawing of a triquetrum, one of the few instruments mentioned by Copernicus.

7f. Michael Maestlin's note identifying Andreas Osiander as the anonymous author of the Ad lectorem on the back of the title page of Copernicus' book

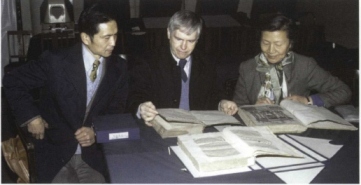

8a. Owen Gingerich with Shida Weng and Peishan Li examining the second and third editions of De revolutionibus and Kepler's Rudolphine Tables in the rare book room of the National Library of China, Beijing, 1985.

8b. Owen Gingerich examining the most important first edition of De revolutionibus in the Western Hemisphere, in Yale University's Beinecke Library. His own copy of the second edition lies just beyond the first.

Our opportunity came in the fall of 1985. Miriam and I decided to begin an Asian tour in China, and Shida provided a timely invitation. Besides the mandatory visit to the Great Wall and a trip to see Xi'an's astonishing terra-cotta army, I had two specific goals: I wanted to see the Pascal calculating machine sent to Beijing possibly by Louis XIV, and I hoped to inspect the two copies of De revolutionibus brought to China by Jesuit missionaries in 1618.

For centuries astronomers were the major consumers of numbers. In 1623-24 Kepler's friend Wilhelm Schickard (whose well-annotated De revolutionibus is today in the Basel University Library—see plate 7e) designed a calculating machine to assist in Kepler's continuing numerical problems, but unfortunately it was destroyed in a fire before it could be tested in real calculations. The oldest surviving mechanical calculating machine, from 1644, was made by the French mathematician Blaise Pascal, not for astronomers but to assist his father with financial calculations at the customs office, and a few original examples survive.* In the seventeenth century wealthy Europeans coveted the silks and porcelain that came only from China, but the Chinese were not interested in very much of what Europeans had to offer. One exception was fancy clocks, and another was automata, such as mechanical dolls that danced to the tunes of mechanical music boxes.

The Pascal calculating machine was a novelty of precisely the sort to intrigue the Chinese court, and in researching the history of automatic calculating devices for a Charles Eames exhibition, I had learned that there were two Pascal machines in the Royal Palace in the Forbidden City in Beijing. But even when Miriam and I arrived in Beijing, Shida Weng was not at all certain that we would be given permission to see the Pascal machines, which were in a restricted section of the Royal Palace. Then, as mysteriously as many things in China, the permission was granted. We were taken into rooms not ordinarily open to visitors, and there the devices were gently lifted out of their packing boxes. One proved to be the genuine French import. The other, we were surprised to discover, was an almost exact Chinese copy. Later, when I reported our experience to Joseph Needham, the eminent English student of Chinese science and civilization, he allowed that we were probably the only westerners to have examined these machines in the past half century.

The two copies of De revolutionibus arrived in China about thirty years earlier than the Pascal calculator. Shida Weng himself had never before gained permission to examine these books, and seeing them was only slightly less of a cliff-hanger than viewing the Pascal machines. We were taken to the National Library, which must have been a very suitable and handsome structure when it was built in 1931, but was in 1985 (like many libraries around the world) awaiting more commodious quarters.* The rooms were filled with readers save for the one reserved for the works of Marx and Lenin, which was as quiet as an undiscovered tomb. The rare book room was chilly and singularly austere, but three volumes I had specifically requested were on reserve for us: a second edition of De revolutionibus and also a third edition from 1617, both of which were brought by Jesuit missionaries in 1618; and a copy of Kepler's Rudolphine Tables, which obviously came somewhat later since it wasn't published until 1627 (plate 8a). The Jesuit library was not nationalized until after the Chinese revolution of 1949. In this action the Chinese were singularly backward, since most of the Jesuit libraries in Europe had been nationalized a century and a half earlier.

The two editions of De revolutionibus had traveled to China at an especially interesting time, because the Vatican decree prohibiting Copernicus' book "until corrected" had appeared in 1616, but the corrections were not issued until 1620, by which time the two Jesuits who had brought the books had already made their way to Beijing. The 1566 edition, brought by Giacomo Rao, included Rheticus' Narratio prima, which had been reprinted as an appendix; Rao crossed off Rheticus' name on the title page because as a Lutheran Rheticus was considered a "first-class" author, meaning that all of his works were banned, but the Narratio prima was not excised (as sometimes happened). However, the Lutheran names at the beginning of the appendix were struck out. Otherwise the book was uncensored and unannotated.

The draconian censorship of the entirety of Book I, chapter 8, the only known copy in which the more severe form of the Vatican's excisions was performed. Biblioteca Statale, Cremona.

The third edition, brought to China by Nicholas Trigault, S.J., was treated slightly differently. Chapter 8, on the refutation of the ancient arguments against the mobility of the Earth, was marked in Latin, "This chapter is not to be read." This must have been a shrewd guess, probably on Trigault's part, because among the remarks contained in the 1620 decree was the statement that chapter 8 could be excised in its entirety. The decree went on to say, however, that because students might wish to see how the arguments of the book were developed, it would be satisfactory simply to reword two of the passages in the chapter. Presumably, this instruction never caught up with Trigault. Among the nearly six hundred copies examined in my survey, only one suffered the more draconian treatment: The second edition in Cremona has the central leaf of chapter 8 sliced out, but the beginning and ending of the chapter were printed with uncensored material on the other side, so sheets of paper were pasted over this prohibited part. I'm not sure who would have been put off by the warning in Trigault's third edition, but it does offer a fascinating window on the mindset of the Vatican workers in the early seventeenth century.

* Copernicus used the word explodendum, which means "being hissed or clapped off the stage." The Oxford English Dictionary confirms that this is also the original but now obsolete meaning of the English word explode, which did not pick up the modern definition of "to blow up with a loud noise" until around 1700. Shakespeare never used the word despite its theatrical connotation, but his contemporary Kepler did, undoubtedly in an echo of Copernicus' usage, when in the introduction to his Astronomia nova he wrote (in Latin), "First, Ptolemy is certainly hissed off the stage." Kepler may have been sensi-rized to the word by Galileo, who used it in his first letter to Kepler, in 1597.

* "Thou hast fixed the Earth immovable and firm, thy throne firm from of old; for all eternity thou art God."

† There the matter stood for a decade. Then, in 1971, a French scholar noticed that in a sermon on I Corinthians 10 and 11, Calvin denounced those "who will say that the Sun does not move and that it is the Earth that shifts and turns." Calvin neither mentioned Copernicus by name, nor did he invoke any Scripture against heliocentrism itself. In fact, it has been cogently argued that Calvin was alluding to a quotation in Cicero brought on by a debate with one of his understudies who had fallen out of his good favor. So the jury is still out on Calvin's opinion, if any, on Copernicus and his book.

* One copy is in the British Library, and the other is in the library in Greifswald, Germany.

* Despite the makeshift arrangement, the photograph was good enough to appeaf in the appropriate Complete Works volume of the Polish Academy of Sciences.

† Such indifference was characteristic of the period: Kepler sometimes spelled his name Keppler.

‡ The Michelin Guide characterized Ariosto's Orlando Furioso as the Renaissance equivalent of Gone with the Wind.

* Incidentally, Andrew Dickson White, though an unreliable guide to the religious reception of Copernicus' book, did own a first edition of De revolutionibus, now pteserved in the library of Cornell University. A previous owner had been the English antiquary John Aubrey (1626-97), and since the book had spent the critical years in England, it was not censored.

* SeveraI examples are found in the Conservatoire des Arts et Metiers in Paris, another in the historical museum in Clermont-Ferrand (Pascal's hometown), one in the State Mathematical-Physical Salon in Dresden, and one in the IBM Collection in New York.

* A new building was opened in October 1987; it is now the largest single library building in the world.