DURING THE great Copernican Quinquecentennial of 1973, two distinguished scholars had been assigned a private limousine to get them from Warsaw to Copernicus' birthplace, Torun. Edward Rosen, the dean of Copernican studies, and Willy Hartner, Europe's leading historian of the exact sciences, emerged from the car no longer on speaking terms. Hartner had had the audacity to suggest that Copernicus and Rheticus could have discussed astrology. After all, in the Narratio prima Rheticus had entitled one section "The kingdoms of the world change with the motion of the eccentric" and added that "this small circle is in truth the Wheel of Fortune." Surely, he would not have included the statement without having talked about it with his mentor. To Rosen the very idea of such a conversation was anathema. To him Copernicus was the model modern scientist, unpolluted by such notions as planetary influences.

By today's historiography, of course, Rosen's view was hopelessly anachronistic. Copernicus lived in an era when astrological ideas permeated academia. The astronomy curriculum was designed to teach advanced students the use of planetary tables so that they could calculate the positions of planets needed for constructing a horoscope that would show the aspects of the sky at a patron's birth. Cracow University had two astronomy professors, one in the arts faculty and the other in the medical faculty, the latter expressly for teaching the doctors-to-be how to use the stars for medical prognostications. Domenico Maria Novara, the astronomer with whom Copernicus boarded while he studied law in Bologna, published annual astrological prognostications, something Copernicus could scarcely have ignored. And when he returned to Italy to study medicine at Padua, he surely was exposed to more astrological thinking.

A century and a half earlier Geoffrey Chaucer had spiced his Canterbury Tales and his Troilus and Crysede with planetary configurations that held keys to the twists of fate in his stories, and if anything, the astrological ethos had only intensified since his time. Even today our language contains fossil remnants of a sidereal and planetary vocabulary: consider, ascendancy, disaster, jovial, martial, venereal, mercurial, saturnine, not to mention the names of the days of the week.*

Copernicus was born 19 February 1473 at 4:48 P.M. This fact would probably be unknown to us except that it is preserved in an early manuscript horoscope found in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich. It seems unlikely that Copernicus' mother had a clock beside the birthing bed or that the time would have been recorded so accurately. In fact, Renaissance astrology guides point out that the first step in constructing a horoscope was usually to retrodict the time of the client's birth. An elaborate process of deducing the moment of conception by examining the phase of the Moon nine months earlier, and then working forward in time, theoretically allowed the astrologer to construct the missing information. Since a critical feature of each horoscope is the degree of the zodiac that was just rising at the moment of birth (the so-called ascendant), and because this changes on average every four minutes, a fairly precise time of birth is required. The chances are extremely high that Copernicus' birth moment was simply calculated,†

All the available biographical information on Rheticus reveals his passion for astrology. Curiously, there is not a shred of evidence that Copernicus had any interest in the subject, even though he could hardly have avoided learning the standard rules of its practice. Given the ethos of the times, Rheticus and Copernicus must certainly have discussed the topic. Copernicus was surely not naive; he must have realized that astrologers would constitute a good fraction of the market for his treatise.

The horoscope for Copernicus that establishes the astronomer's birthday. Bayerische Staatshibliothek, Munich, Cod. Lat. #27003, folio 33 verso.

WELL IN TUNE with the realities of the sixteenth century was Rene Taylor, director of the art museum in Ponce, Puerto Rico, who had come to me with an unusual request several years before my Copernicus chase began. Could I draw up a horoscope for the laying of the cornerstone of the Escorial Palace north of Madrid, an event that took place on the Feast of St. George in April 1563? I was naturally curious as to what lay behind his request. It turned out that he had a list of books in the library of Juan de Herrera, architect of the Escorial. There were few books on architecture but many on magic, astrology, and astronomy. Taylor figured that Herrera would naturally have used astrology to choose the time of day, and perhaps even the day itself, for the cornerstone ceremony. Because I was then in my spare time computing planetary positions from ancient Babylonian times to the present, I figured I could easily help him test his hypothesis.

Little did I then appreciate that every major Renaissance astrologer seemed to have his own way of dividing up the sky into the so-called astrological houses. Furthermore, for historical studies it was necessary to know not where the planets really were but where the astrologers thought they were (which was often quite another thing). In agreeing to help Taylor, I got myself in deeper than I had intended, but eventually I came up with a credible sixteenth-century horoscope, and I helped Taylor find a real astrologer, someone with a genuine thirteenth-century mind,* to interpret it and to convince him that the time and day were deliberately selected to be astrologically propitious.

Herrera's library had included not one but two examples of Copernicus' De revolutionibus. After my quest began, I looked forward to the opportunity to inspect them in the Escorial itself, and in 1977 I finally had the occasion to visit the splendid library with the astronomical frescoes that had been at the heart of Taylor's researches. In the course of chasing after copies of Copernicus' book, Miriam and I had visited some spectacularly decorated rooms. The library at the Melk Abbey in Austria comes to mind, as do both the Strakhov Monastery and the Clementinum in Prague. The original reading room of the Vatican Library is pretty grand as well, and the Osterreichische Nationalbiblio-thek in Vienna is close to being in the same league. Alas, we didn't actually sit in any of these wonderful spaces, including the Escorial, to study De revolutionibus. Those ornate halls now function as art galleries, and the reading rooms are not so stately. So for total experience, the Wren Library at Trinity College, Cambridge, and Duke Humphrey's Library at the Bodleian in Oxford take the laurels.

Still, we took a special delight in actually seeing the Escorial images. The vaulted 175-foot-long arcade provided space for strategically positioned showcases of rare books and manuscripts as well as an ornate armillary sphere, and the hall was lined with Herrera's specially designed bookcases of ebony, cedar, orangewood, and walnut. The frescoes individually were not particularly memorable art—the conservative King Philip II, patron of the palace, placed the flamboyant paintings by El Greco elsewhere—but the total effect in the hall was stunning. The arched panels depict the seven liberal arts, beginning with Grammar and Rhetoric at one end, Logic, Arithmetic, and Music in the central three vaults, and Geometry and Astronomy curving over the armillary sphere. There in the bay for Astronomia is Alfonso the Great, patron of the astronomical tables that Reinhold's Copernican-based Tabulae Prutenicae ultimately replaced in the mid-sixteenth century. Facing Alfonso on the other side of the arcade is Euclid, and like the Castillian monarch, he holds astronomical symbols that, according to Taylor, were connected to the horoscope of Philip II. And under the bay is another astronomical fresco, with Dionysius the Areopagite observing the eclipse at Christ's passion.*

The main gallery of the Escorial Library, with itsfrescoes of the seven liberal arts.

The library itself holds one of the world's largest collections of medieval manuscripts, being surpassed only by the Vatican's holdings. In the austere reading room I took a look at the library's copies of De revolutionibus. Its first edition is in a green pigskin binding blind-stamped with the arms of Philip II—that is, an impressed but uncolored design. Apparently the king had bought the copy early on, in 1545 when he was eighteen. He didn't write in it, and there is no way to know if he actually read it. The king was a formidable collector of books, and this one became part of a gift of more than 4,500 volumes he presented to the Escorial monastery library in 1576.1 was disappointed not to find direct evidence there of either of the copies Juan de Herrera was known to have owned. The Escorial suffered a horrendous fire in 1671, and if Herrera's volumes were first editions, they might have perished then. There are, however, two unattributed copies of the second edition in the Escorial collection. If the two copies Herrera owned were of the 1566 Basel edition (entirely possible, for he was also collecting books after that time), one or both of these copies now in the Escorial might have originally belonged to the architect and escaped the fire. We will probably never know whether the Escorial architect actually read the Copernican tome, because these copies have no annotations, and I never found any other copy associated with him.

As I EXAMINED many annotations in libraries throughout Europe and North America, virtually always in Latin, I gradually learned to distinguish between various national writing styles. But no matter the nationality, there are both neat, lucidly legible hands and some so messy or idiosyncratic that reading them provides a test of wit and patience. One sprawl on a title page in the National Library in Rome turned out to be relevant to astrology, but for many days it defied both me and my colleague Jerzy Dobrzycki as we tried to decipher it. Early one morning, when I was still half asleep in bed, the reading came to me. Many seemingly brilliant insights occur when I'm in such a semiconscious state, only to dissolve into triviality in the clear light of dawn, but this rare exception rang true. Dobrzycki was visiting me at the time, and he expressed considerable skepticism that I had managed to crack the inscription, but he was soon obliged to concede. I was quite pleased with my success, since I could so seldom best him at a Latin transcription. The phrase read, " Vidit P. Rd Inquisitor inde Corrigatur si qua erant astrono-miae judiciare die 2 apl 1597" (The Reverend Father Inquisitor saw it so that it would be corrected if there were any judicial astrology, on 2 April 1597). In other words, the book passed muster because it contained no astrology. Ed Rosen would have been very pleased.

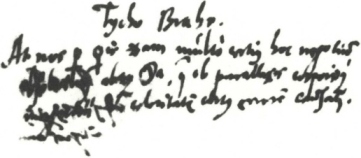

Sometimes an annotation in a cryptic hand seemed almost impossible to decipher. For example, Dobrzycki and I puzzled for a long time over the following note in a copy of De revolutionibus at the National Library of Russia in St. Petersburg (here considerably enlarged).

We recognized the third symbol in the first long line under the name Tycho Brahe as the letter p with a horizontal bar through the tail, the standard Latin abbreviation for per, but what came next baffled us. I finally showed it to Emmanuel Poulle, the distinguished French paleographer who had helped in many ways with the census, and he almost instantly read it as "At nos per Veneris stellam multo certius hoc negotium observavimus alioquin Luna,* etc." With that I felt rather like a kindergartner, for Jerzy and I had often encountered the planetary symbols in the notes, but in this context we had totally missed the traditional symbol for Venus. These symbols are tiny planetary logos, depicting a recognizable characteristic of each member of the Greco-Roman planetary pantheon:

The symbols for the five naked-eye planets are given here in their traditional order, beginning with Mercury with its truncated caduceus, the serpent-entwined staff of the swift messenger of the gods. Venus' mirror is obvious (the second symbol), as is the spear and shield of Mars (the third). Jupiter's symbol is a stylized thunderbolt, while Saturn's is the scythe of Father Time (the last in the row).

In hindsight, the printing methods of the 1970s that I considered for the Census in its early stages seem very primitive by today's standards. Many entries were typed and retyped by my secretary as additional details and identifications became available. Although today I can hardly remember what a Spinwriter is, for some years it was the device of choice for a reasonably legible computer printout. In retrospect, some of the world's ugliest books since the invention of printing with movable type were produced in that decade.

As larger and faster computers arrived on the scene, computer-typesetting became an everyday reality. Then I realized that for the typography of the Census I would need the symbols both for the planets and for the signs of the zodiac—zodiacal signs because astronomers in those days frequently designated astronomical longitudes by a system in which the ecliptic* was divided into twelve equal segments of thirty degrees, for example V 14°. Here the symbol for Aries derives from the horns of the Ram. I wanted my Census to have symbols that reflected their historical roots, so I commissioned the California typographer Kris Holmes to add these characters as well as the planetary symbols to her Lucida computer font. I sent her images from sixteenth-century astronomical tables, and here is the typography we agreed on.

The meanings of some of these symbols are pretty obvious: the rippling waves for watery Aquarius, the balance for Libra, the arrow for Sagittarius the Archer. Others are more abstract, such as the bushy mane of Leo the Lion, the paired lines for Gemini the Twins, or the horns and face of Taurus the Bull. (Our alphabet may have derived from a denser set of astronomical symbols beginning with Taurus; tipped ninety degrees, the Taurus symbol becomes an alpha.) The two most confusing are the symbols for Scorpio, with the pointed stinger in the scorpion's tail, and Virgo the Virgin, which carries the standard medieval abbreviation for Maria, a capital M with the crossed tail, a shorthand indicating additional letters.

As with the abbreviation for Maria, the early annotators frequently designated omitted letters with a short line above, below, or behind the nearest letter or over the entire word. The commonest abbreviation is a bar over a vowel, indicating a missing n or m. The system works up from there. For example, oa stands for omnia, or ro can represent ratione, something of an all-purpose word in the technical Latin context, meaning everything from "reason" to "theory" to "thought." In working with the Latin script, I quickly learned to distinguish between p for per and JD for pro. It was much harder to keep track of g for qui, q for quae, and q for quod. In the Census these words are always spelled out, so fortunately I didn't need a virtual type box quite as large as the one Petreius used for setting De revolutionibus*

The use of abbreviations was generally the compositor's option in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. When it was necessary to squeeze the words to get them to fit in a line, he would select more abbreviations from his type box. A few lines later, with a more relaxed spacing, the word might well be spelled out in full. It's particularly interesting to see this process at work in Galileo's Sidereus nundus. The final page is thoroughly sprinkled with abbreviations as the typesetter exercised full control to make sure that the text didn't run over by a few lines onto another sheet. That happened in De revolutionibus, too, at the end of Book V where the typesetter jammed in far more than the average number of abbreviations. The effect also happened in the middle of the signature* marked s in order to finish a chapter before four pages of tables. Probably a virtuoso compositor took over, squeezing in abbreviations like tpe for tempore or qn for quando.

IN 1974 I made two complicated, adventuresome book-hunting trips to Europe, adding a few dozen more Copernicus copies to the census. At Hertford College in Oxford I encountered a particularly eccentric librarian who suspected me of being a fraud, but he did show me Hertford's unannotated second edition, which had been owned by Thomas Finck, the seventeenth-century physician and mathematician who added the words tangent and secant to the trigonometric vocabulary. That April trip eventually carried me on to Egypt, where the astronomers had been given funding for a Copernican quinquecentennial commemoration, so they enlisted me to add an international note to their one-year-late affair. But in between these stops I went to a conference in Capri that led to a quite unexpected finding about Galileo.

I knew that Capri was a famous resort destination, but I was quite surprised to discover that the island had no beaches. Just getting there proved to be both a figurative and literal cliff-hanger. The plane from London to Rome was an hour late, and by the time I could catch a high-speed train to Naples, it was one scheduled to arrive five minutes after what I had been led to believe was the last ferry to the island. I had nervous visions of hiring a fishing boat at some exorbitant rate to take me there, little realizing what a substantial distance was involved. Fortunately, the information was wrong; by great good luck I had got out at the right train station, the one next to the ferry terminal, and I just had time to catch what really was the last ferry. I reached the storybook island at dusk, ascended the towering cliffs by funicular, and was soon in the company of some of the leading historians of the scientific Renaissance.

My role at the conference was to comment on a paper presented by Guglielmo Righini, director of the observatory in Florence. Righini examined in detail Galileo's early drawings of the Moon in an attempt to date when they were made. In 1609 Galileo had learned about a Dutch spyglass that was being sold in the major cities of Europe; he figured out how it could be done and effectively turned what had been a toy into a scientific instrument, with which he discovered the craters on the Moon. His book announcing his discoveries, Sidereus nundus, or "The Sidereal Messenger," was published in March 1610, so the possible dates of his observations were fairly limited. Strangely enough, no one had attempted to pin specific dates onto the two surviving sheets of Galileo's observations, probably because no one before Righini had believed that they were accurate enough to warrant such an investigation. It fell to me to point out that there were serious problems with the images published in Sidereus nundus, which varied in critical ways from the original ink-wash drawings, and that the dates Righini picked were not necessarily unique.

Although Righini's analysis was flawed, his paper provided the catalyst that ultimately established a precise dating of Galileo's lunar observations and thereby gave an accurate chronology for the swift genesis of his astronomical discoveries. Galileo undoubtedly found the craters on the Moon before he was prepared to record them, but having decided that his discovery was worthy of publication, he subsequently equipped himself with ink, brushes, and a sheet of special artist's paper, and on the evening of 30 November 1609 made two careful depictions of the cratered lunar surface. At four further times throughout December he added images to his sheet, making six drawings in all. But in the week of 7 January 1610 another series of observations, not of the Moon but of Jupiter, suddenly gave an urgency to his publication schedule. After discovering four companion stars revolving around Jupiter, and filled with excitement but fearful of being scooped, he rushed to publish his observations. His Sidereus nundus was in print in just over six weeks after he had delivered the first installment of his manuscript to the printer in Venice—an extraordinarily quick turnaround even by today's standards.

Galileo's ink-wash drawing of the Moon on 19 January 1610 and his uncompleted horoscope for Cosimo de' Medici; a completed horoscope is on the other side of the sheet.

In a letter to Kepler written in 1597, Galileo had allowed that, privately, he accepted the Copernican cosmology. In public, however, for more than a decade Galileo apparently never whispered a hint of his radical beliefs. That all changed in 1610 with the publication of Sidereus nundus. Some critics had resisted the idea of a moving Earth, asking how an Earth in orbit around the Sun could keep the Moon in tow. To them, Galileo pointed out that Jupiter, which everyone agreed was in motion, managed to retain its companion moons as it moved across the sky—a powerful Copernican counterargument to the objectors. From this point on, Galileo became ever more open in his defense of the Copernican system, apparently stimulated by the astonishing novelties his telescope had revealed.

But Galileo had a second agenda in writing Sidereus nundus: He was keen to give up his professorial post in Padua to become the mathematician and philosopher to Grand Duke Cosimo de' Medici in Florence, and to that end he dedicated his book to Cosimo and he named the Jovian moons the "Medicean stars." In this plan he succeeded, and Florence became his home for the rest of his life.

I made a second trip to Italy in July 1974, and in Florence I discovered what turned out to be Galileo's secret weapon in getting the job at the Medicean court. At the time of the Capri conference I had not actually seen Galileo's original ink-wash drawings of the Moon. Two pages of the lunar images had been carefully reproduced in the so-called National Edition of Galileo's works and correspondence, published in twenty volumes at the turn of the twentieth century, and it was very convenient to use those reproductions in preparing my commentary on Righini's paper. But with my curiosity sparked, I took advantage of a visit to Florence to examine not only Galileo's sparsely annotated copy of De revolutionibus in the National Library but also his astronomical manuscripts. I had long supposed that Galileo was not the sort of astronomer who would have read Copernicus' book to the very end. Even on that seminal evening with Jerry Ravetz, when we had speculated how few early readers of Derevolutionibus there might have been, we had been reluctant to include Galileo in the list of readers. Unlike Reinhold or Maestlin or Kepler, he was not interested in the details of celestial mechanics. Still, when I saw the copy in Florence, my reaction was one of skepticism that it was actually Galileo's copy, since there were so few annotations in it apart from the standard censorship decreed by the Inquisition in 1620. Eventually, as I became more familiar with Galileo's hand, I realized that my skepticism was unfounded and that it really was Galileo's copy.

The Galileo manuscripts, on the other hand, proved to be quite fascinating. To my surprise, I discovered that the reproductions of the sheets of lunar drawings in the National Edition were not entirely complete. A single drawing of the Moon on a second sheet, now dated to 19 January 1610, had been published, but an astrological horoscope that shared the page was nicely suppressed. Clearly, it would have diminished Galileo's heroic status as the first truly modern scientist to admit so conspicuously that he was capable of drawing up horoscopes.

I asked Righini's wife, Maria Luisa Bonelli-Righini, director of the History of Science Museum in Florence, for help in obtaining color slides of the horoscopes (for there was another on the other side of the sheet). They arrived just in time for me to add a postscript to my Capri paper, and there I pointed out that one of the horoscopes could be dated to 2 May 1590 from the positions of the planets it contained. Afterward I felt rather dim-witted that I hadn't taken the next step. Righini, alerted to the horoscopes by my slide request, promptly realized that the date was Cosimo's birthday, and that Galileo had drawn up a birth horoscope for his prospective patron. Indeed, in the dedication to Sidereus nundus, Galileo dwelled on the theme of Jupiter's position in the horoscope, writing with obsequious flattery, "It was Jupiter, I say, who at your Highness's birth, having already passed through the murky vapors of the horizon and occupying the midheaven and illuminating the eastern angle from his royal house,* looked down upon your most fortunate birth from that sublime throne and poured out all his splendor and grandeur into the most pure air, so that with its first breath your tender little body and your soul, already decorated by God with noble ornaments, could drink in this universal power and authority." Astrology never again played a public role in Galileo's work, unlike Kepler's, which included a pamphlet entitled The Sure Fundamentals of Astrology and another defense where on the title page he urged critics not to throw out the baby with the bathwater, saying that he was searching for a few kernels among the dung of traditional astrology. Nevertheless, astrology was part of the ethos of the times, and it is surprising that there is nary a hint of it in De revolutionibus. Nor is there any trace of interest in astrology in anything else that remains from Copernicus.

* Consider = cum sidera = "with the stars"; disaster = "against the stars" (ill-starred); et cetera,

† in Johannes Kepler's manuscript legacy there are, among many others, two horoscopes he drew up for himself, one for his birth and the other for his conception. Once when I projected slides of both side by side in my class, a young woman in the second row raised her hand to inquire why rhere were only seven and a half months between the two horoscopes. "Oh," I replied, "Kepler chose his parent's wedding night for the date of the conception." Needless to say, this remark completely cracked up the class.

* The expert was an authority on Islamic art of the Middle Ages, who was well in tune with that era.

* There couldn't have been an eclipse at that time. Jesus was crucified the day after Passover, which is locked to a lunar calendar so that it falls near the time of full moon. Solar eclipses occur only at the time of new moon.

* (But we have observed this business with more certainty via the planet Venus than using the Moon, etc.) The note refers to Tycho's method of comparing the position of the Sun with the stars, which is difficult because they are not visible at the same time. Tycho connected them by measuring the distance from the Sun to Venus (which is visible in the daytime), and at night connecting Venus with the stars. In the text next to the annotation Copernicus described using the Moon for the same purpose. Tycho's alternative method gave improved accuracy.

* The ecliptic is the great circle of the Sun's path through the zodiac. The paths of the Moon and planets are slightly tilted with respect to the ecliptic, each orbit crossing the ecliptic at two points called the nodes, separated by 180°. An eclipse can take place only when the Moon is near its node, crossing the ecliptic (with the Sun also at a lunar node), hence the name ecliptic.

* Not counting punctuation, numbers, Greek letters, or the zodiacal signs and planetary symbols, the Nuremberg printer used just over thirty special symbols or ligatures in addition to twenty-three lowercase letters (noy, v, or w, which do nor occur in Latin) and twenty-three uppercase letters (noy, U, or IV).

* A signature in De revolutionibus comprised four printed leaves, or eight pages. Each signature was coded wirh a sequential letter to assist in the assembly of the book.

* The two most important zones, or "houses," in a horoscope are the ascendant (the part of the ecliptic circle about to rise over the eastern horizon), here called the eastern angle, and the midheaven (the part of the ecliptic circle about to cross the meridian). In Cosimo's horoscope, Jupiter was in the midheaven, while the sign of Sagittarius, the so-called day domicile of Jupiter, was in the ascendant.