LONG BEFORE I met Alexander Pogo I heard stories of his extraordinary career. Born in St. Petersburg, Russia, in 1893, he had begun engineering studies in Liege in 1911. When the Germans invaded Belgium during World War I, he became a prisoner. After the war he finished his degree, but rather than returning to his native land, by then the Soviet Union, he went to Athens, where he landed a job measuring the fallen column drums of the Parthenon on the Acropolis, preparatory to reerecting some of them. Later he emigrated to the United States, where he earned a doctorate in astronomy from the University of Chicago. In the meantime, he had become fluent in eight languages. With this unusual background and his facility with languages, he became an assistant to George Sarton, the man considered the father of modern history of science.

Sarton's office was in Harvard's Widener Library, though his salary, as well as Pogo's, was paid by the Carnegie Institution of Washington rather than by Harvard. Those who knew Pogo at Harvard remembered that he had his own pet peeves, such as the fact that the great Canon of Eclipses compiled by Theodor von Oppolzer in the 1880s omitted the so-called penumbral lunar eclipses, when the Moon was touched only by the outer shadow of the Earth.

As Sarton approached his retirement, the Carnegie Institution, which felt some responsibility for Pogo, decided that he could play a useful role as librarian for the Mount Wilson and Palomar Observatories, which it funded in California. Thus, in 1950 Pogo transferred from Cambridge to Pasadena, leaving in time to miss the famous "I go Pogo" riot when Harvard students tangled with local police as they got a bit too rambunctious waiting for an appearance by cartoonist Walt Kelly, who was then spoofing the 1952 American presidential elections in his Pogo comic strip.

Not only did Alexander Pogo become responsible for the Observatories' library, but he became de facto rare book librarian at the California Institute of Technology. Dean Earnest Watson was building a rare science book collection for that institution, and Pogo took me to see it in 1972 when I came searching for copies of De revolutionibus. With a touch of pride he told me that Cal Tech's copy of the first edition was not the initial one received from Dawson's of Pall Mall, an eminent rare book firm in London. When the first copy came, he inspected it carefully, and his eye caught a page that was wrong, a leaf from a second edition inserted among the leaves of the first edition. This substitution was possible because the 1566 second edition was virtually a page-by-page reprint of the first. Each signature of four leaves ended on exactly the same word in both the 1543 and 1566 editions. The easiest giveaway was the fact that the larger initial letters of the chapters differed in the two editions, but there were other differences; for instance, the first edition labeled the diagrams with lowercase letters, whereas the second always used capitals. But the similarity of the pages was such that they could escape notice with a casual inspection. Thus Pogo had every right to be proud of his acute observation. The book went back, and in due time a replacement arrived. But, as it turned out, this was not to be the end of the story.

Important sources for documenting the movement of rare books are the specialist dealer's catalogs, and here I was very lucky to inherit an extensive collection going from the 1930s into the 1960s. These catalogs had been obtained by C. Doris Hellman, a historian of science who concentrated on Tycho Brahe and who was a collector of modest scale but considerable expertise. Included among her several hundred catalogs was an almost complete set from Dr. Ernst Weil, a man I never met but who was probably the first independent book dealer specializing in early science. Collectors like Lord Crawford, who formed important astronomical libraries in the nineteenth century, relied on generalist dealers to acquire their most precious treasures. In particular, Lord Crawford depended heavily on Bernard Quaritch in London, who dealt across the board in rare books. Not until rare science collecting became less rare was there a niche for a specialist dealer, and Weil seized this opportunity.

He first worked with the old firm of Tauber in Munich, but in 1933 he emigrated to England, one of many refugees escaping the Nazi tyranny. There he became a director of the distinguished E. P. Goldschmidt company. His initial catalog, "Classics of Science," offered a copy of Galileo's Diabgo (1632) (with the claim that "the first edition has become exceedingly rare," rather inflated considering that the Dialogo is the least expensive of the great astronomical classics), Kepler's much rarer Astronomia nova (1609), and "Copernicus' first published book," the De lateribus et angulis triangulorum (1542) (again misstated, because in 1509 Copernicus published a now virtually unobtainable translation of moralistic letters by the Byzantine epistolographer Theophylactus Simocatta).*

A decade later Weil struck out on his own, in 1943 issuing his first catalog under his own name. For ten pounds you could buy an autograph manuscript by Isaac Newton, while four pounds, ten shillings would get you the astronomical tables by the female astronomer Maria Cunitia (1650), a book I most recently saw offered for 313,000. In catalogs 4 and 6 he offered a second-edition De revolutionibus, with just enough information for me to identify it with a copy now in a private collection in California. And in catalog 22 there was a first edition of the book containing the cryptic clue "with duplicate stamp of a well-known library." Probably this was the duplicate released from Harvard's Houghton Library. I had discovered that copy in 1976 when I visited the private collection of Henry Posner, a retired advertising executive in Pittsburgh.† His collection is now at the Carnegie-Mellon University.

Weil's nineteenth catalog contained a notice that raised my pulse rate: He proposed making a census of Copernicus' De revolutionibus] "I hope to be able to publish one day a census for which I have collected data for a long time," he wrote. His census never emerged in print, but he was obviously very interested in the subject because, as the pioneering and leading rare science dealer, he had bought and sold a number of copies of the first edition. Weil was no longer alive when I started my own quest for copies of Copernicus' book, but when I inherited the copy of his catalog 19,1 was seized with curiosity. Had he actually started a census? Might it be among his papers somewhere?

It did not take long for me to discover that Dr. H. A. Feisenberger, a bookman who worked for part of his career in Sotheby's book department, had inherited Weil's records; the most important for my purposes was a workbook in which Weil had kept track of some of the more famous science titles as they passed through the market. Weil had made notes, often replete with insider information, on the sale of some thirty first editions of Copernicus' book, not enough for a serious census but nonetheless highly interesting. And though the Cal Tech De revolutionibus had come through Dawson's, it was clear that Weil was the real source.

Weil's notes were terse but immensely illuminating. Many of the copies he listed I already knew about because I had worked carefully through the auction records, but certain mysteries remained. In 1950 Christie's had auctioned the "Hum Court Library" with a first edition that lacked folio 97, but no book answering to that description had turned up in my searches. And in his catalog 19, Weil had offered "the Arthur Ellen Finch copy," but no book matching that provenance had been found.

Weil's workbook was an eye-opener. I found the following entry: "1951 Bought with Scheler Finch copy, last leaf in fac [simile] + Sotheran-Christie copy lacking 1 l[eaf] Made Finch copy fine. Cat. 19, now Calif. Inst. Techn. (Watson tells me, 8/54)." Apparently, Weil, in league with a major Parisian dealer, Lucien Scheler, had bought an incomplete copy at a 1950 Christie's auction, and at about the same time he had purchased privately the so-called Finch copy. What happened thereafter became clear: Weil completed the Finch copy, which lacked a genuine final leaf, using the imperfect Christie's copy, without realizing that the Finch copy had another defect as well, a leaf from a second edition. Dawson's of Pall Mall bought the book from him and shipped it to Cal Tech. When Pogo's sharp-eyed inspection revealed the fault, the book came back. Dawson's returned the book to Weil, who promptly moved the necessary folios to fix up the other copy instead.

Several lines later Weil's notebook read, "9/8/54 made up Sotheran-Christie copy in English XVIIth calf, (now Calif Inst. 8/55)." Among booksellers and collectors there is a long tradition of "making a copy right." This procedure, like rebinding an old book, can be a bibliographical tragedy when historical information is lost, but it can also sometimes be an intelligent step. In any event, making good books out of bad books is a rather commonplace occurrence.

Even I have been a marriage counselor for the occasional pair of handicapped books. Tucked away in an upstairs rare book nook at Allen's in Philadelphia was a rather horrid copy of Tycho Brahe's 1602 book of instruments. Tastelessly bound in modern library-buckram, it lacked six leaves. In their place were photographs on double-weight photographic paper, vintage late 1920s, altogether a rather repugnant assembly, but I mentally filed away this information. Some months later Bruce Ramer, a New York dealer, lamented to me that he had just purchased, sight unseen at a German auction, what turned out to be another wretched copy of the same book, heavily browned and its title page in shreds. "Measure the page size," I told him, "and maybe I'll take it off your hands."

It turned out that the very best pages in Ramer's dilapidated copy were precisely the ones missing in the copy at Allen's, so I bought them both, had the browned pages washed and slightly bleached at the Fogg Art Museum's paper conservation laboratory, and put together a complete book. While I was at it, I asked an English bookbinder if he happened to have any seventeenth-century boards lying around. Luckily, he had a pair of old calf covers of exactly the right size. My Astronomiae in-stauratae mechanica (Machines for the Reform of Astronomy) will never equal the market price of an original unaltered copy, but it cost only a fraction of an unaltered edition.

I now own what is euphemistically called a scholar's copy and is technically known as a "sophisticated" copy. Given today's primary use of the word sophisticated (refined, urbane, cultivated), this may at first glance seem like a contradiction in terms. However, if you consult the Oxford English Dictionary, you will find that the original use of the word is "altered from primitive simplicity; not plain, honest, or straightforward." Indeed, wearing makeup covers up the defects, and that's sophisticated.

Armed with the insider knowledge from Weil's workbook, in 1976 I wrote to Alexander Pogo, asking him to inspect folio 97 of the Cal Tech copy. He was at first somewhat indignant, replying that the sophisticated copy had been exchanged for another copy. But when I pressed him, he made a careful inspection and wrote back a rueful analysis of a coffee splash on the replacement leaf.

In other words (I assumed) the replacement page had been subtly colored to match the beige tone of the rest of the book. Actually, I didn't really understand what he meant until a number of years later, when I had an opportunity to return to Cal Tech. By then there was a special reading room for rare books, including a fine collection of Newtoniana given by Pogo. I had neglected to bring along the folio number of the replacement leaf, so it was very difficult to spot the alteration. When I finally found it, I was amazed to see that a stain had probably been placed on several pages to make the added leaf appear to be integral to the original state!

All this left me puzzled as to what had happened to the Finch copy, the one that had originally been sent to California but returned after Pogo's inspection. Could it have gone back to Scheler, who had half ownership in the copy?

Eventually, in 1982, a copy surfaced at the Scheler firm in Paris, by then managed by Bernard Clavreuil. "Oh, it's a copy that's been around here for about thirty years," he told me. Precisely what happened to it is not entirely clear. Apparently Clavreuil bought yet another imperfect copy, and probably by now the leaves have been even more thoroughly shuffled. On a visit to the shop, Clavreuil handed me the sophisticated copy. Naturally, I surveyed the volume very carefully. I remarked that it evidently contained a number of facsimile leaves. "How could you tell?" Clavreuil asked curiously.

I had noticed that the book had been censored according to the Inquisition's instructions, which meant that corrections were specified on eight different pages. Yet in Clavreuil's copy not all the expected places displayed the censor's tracks. The pages lacking the censorship marks were clearly replacements.

"Well," I said, "this is a copy that has been censored according to the standard instructions from Rome. But on the facsimile leaves the censorship is missing." This was true, but mostly I was just letting him know that forgeries give themselves away by a variety of clues. The real detection came from the watermarks.

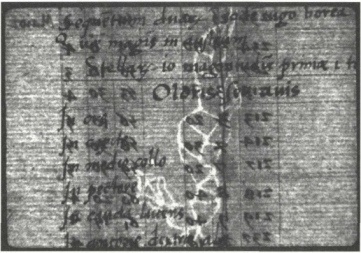

WHEN A SHEET of paper was made in the sixteenth century, the rag fibers were lifted out of the slurry on a fine screen that had strengthening wires spaced every few centimeters apart. These wires produced a characteristic pattern of slightly thinner paper called the watermark—in this specific case called chain lines. Actually, the watermarking is more subtle than just the chain lines. Papermakers usually added an additional wire logo to the form, thereby placing an identification mark on the sheets. In Copernicus' book, the paper contains the letter P on each sheet.*

Petreius printed his edition on sheets measuring 40 by 28 centimeters, a standard size known as pot paper. These dimensions have the proportion √2 to 1, which means each time the sheet was folded down the middle, the resulting page retained the same ratio of the sides, just like the metric A pages currently used in Europe. Petreius printed two pages side by side on the sheet, and then two more on the opposite side. When folded, the sheets produced two conjugate leaves. The technical bibliographic description of De revolutionibus is "a folio gathered in pairs." This means that two separate folded sheets were used, one inside the other, to make a signature of eight pages. Each signature was given a letter, and each leaf within it a consecutive number, so the leaves of a signature could be designated, for example, as C1, C2, C3, and C4. The conjugate of C1 was C4, and C2 was with C3. The P watermark appeared only once on a sheet, so only one leaf of the conjugate pair will show the symbol. Either C1 or C4 will have it, and either C2 or C3.

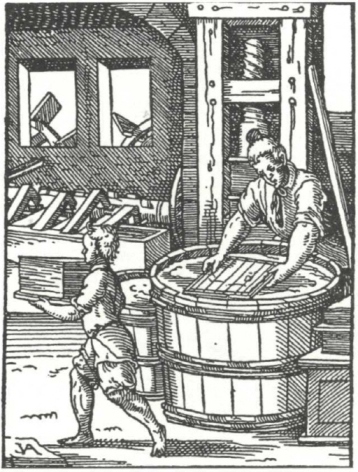

The papermaker lifts a thin layer

of slurry onto the framewhose

wires will produce the watermark

on the sheet of paper, from

Jost

Amman's 1568 woodblock-

conjugate

In Clavreuil's copy, the spacing of the chain lines of the paper was just right, but the P watermark was totally lacking, a clear giveaway for the facsimile leaves. I should hasten to point out that Clavreuil was making no secret of the problematic state of the book; his price clearly flagged the fact that she was a very sophisticated lady. By and by, the book was sold to an undisclosed buyer, so I don't know whether the current owner has any notion about the sophisticated nature of his bargain-priced but still costly first edition.

Sophistication can take various forms, not all equally benign. I vividly recall a visit to Jake Zeidin, a famed Los Angeles dealer whose various specialties included early science. He thrust into my hand an open book (not a Copernicus) with the challenge, "Which side is the facsimile?"

I first examined the watermark. Holding the pages to the light, I checked the chain lines on Zeitlin's book. Both sides of the opened page spread matched. The facsimile had been made on old paper of the correct sort.

The bookbinder from Jost Amman's woodblock in Hans Sachs' Eygentliche Beschreibung aller Stande (Book of Occupations) (Frankfurt a. M., 1568).

Next, I scrutinized the bite of the type, the way the individual letters pressed into the paper. It was very hard to tell which side was false, but I made a shrewd guess based mostly on very slight differences in the impression. Jake smiled and turned to the pastedown leaf inside the front cover, where he had written which pages were replacements. I had guessed right. The problem was, he had recorded the information in pencil, and there was no way to guarantee that subsequent owners would be so scrupulous. In any event, it was an educational experience for me to see how cleverly the facsimiles could be made.

Another curious case of a sophisticated copy is the De revolutionibus in the Dibner Library at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History. An inconspicuous marginal wormhole goes through a substantial part of the book, but it stops at the errata leaf and then continues on the other side. Obviously, the errata leaf came from elsewhere. Only about 30 percent of the copies include the errata leaf, which was printed immediately after the regular print run, but the majority of copies apparently never got such a sheet. Purist collectors would prefer to see a copy with the elusive leaf present. Because Petreius printed the errata on whatever sheets of paper were available, the paper itself gives no guarantee regarding the authenticity of the errata leaves. I would suppose that the Dibner's errata leaf is genuine and was simply lifted from some other copy, but it is hard to be certain.

The watermark on Copernicus' manuscript in the Jagiellonian Library in Cracow. Charles Eames made the picture by backlighting the page so that the mirror image the back side of the leaf is superimposed on that fromthe frontside of the manuscript.

Sometimes a book passes through an auction with its faults clearly mentioned, only to reappear for sale with nothing missing. In 1979 a second-edition De revolutionibus clearly specified as incomplete came under the hammer at Van Gendt, a major auction house in Amsterdam, and was purchased by Librarie Thomas-Scheler in Paris. Subsequently, it was listed in a bookseller's catalog from Geneva, with no mention of any defects. I asked Bernard Clavreuil what had happened, and he replied unabashedly that he had commissioned two facsimile leaves, and he even gave me photocopies to show how good they were. He added that the restored book had gone into the collection of P. Z., but he didn't reveal who P. Z. was. So there was another challenging mystery for me.

Who was P. Z.? After making some inquiries in Paris, I had my suspicions, but for ten years I couldn't be sure.

Then, in 1995,1 got a call from a prominent New York dealer. "We've just bought a second edition at a Paris auction, and I've got a question about the final leaf with the printer's anvil emblem," he said. "It's wrong-way around and looks fuzzy and fake."

I inquired what sale was involved, for it had been hard for me to keep track of the Drouot auctions because it is not a unified auction house like Sotheby's or Christie's, but rather, an umbrella organization for a conglomerate of dealers. The sale of Phillipe Zoumeroffs collection, he informed me.

"Jackpot!" I thought, and then I broke the news. "Are you aware that two leaves are in facsimile?"

There was a stunned silence at the other end of the phone. "How do you know?"

"Because Bernard Clavreuil gave me copies of the facsimiles."

That information undid the sale. The book was returned, and eventually Drouot offered it again, noting that the pages had been added but without a clue that they were actually facsimiles. It is only fair to add that eventually I acquired the copy, took out the two facsimile leaves, and replaced them with genuine leaves from a broken copy I still own. As for the anvil leaf, I'm sure it's genuine, but like most of the copies of that edition, it has the printer's mark very fuzzily printed. In 1999 I sent the book to the Reiss auction in Germany, where it fetched DM 26,000 plus the 15 percent hammer fee, and since its history is fully documented in my Census, there is no secret about its checkered past.

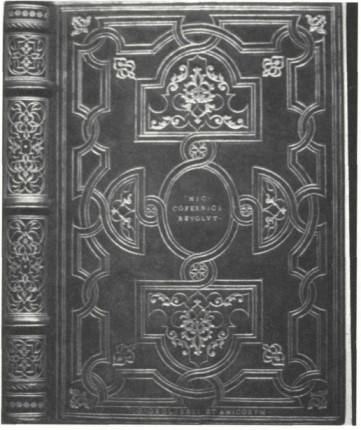

I FOUND THE wildest case of sophistication, if it can be called that, in one of the most unexpected locales. The trail that eventually led to a copy in the Victoria and Albert Museum started in 1976 when I investigated a printed reference work called Book-Prices Current, whose annual volumes list the rare books sold in London in that year. In one of the early yearbooks I found a reference to a first-edition De revolutionibus offered at the 11 November 1897 auction by Sotheby, Wilkinson, and Hodge under the heading "A collection of books formed by an amateur." The book was described as having a richly tooled binding from the famous sixteenth-century French collector Jean Grolier. I perked up when I saw this entry, because I hadn't by then found any copy with a Grolier binding. However, the auction description went on to say, "Note—the books in this library were more remarkable for their binding than for their rarity. The bindings, though modern, were historically correct. They were, in fact, modern imitations of very high quality." In other words, fakes.

Grolier formed such a distinguished library, in fact, that the book collectors' club in New York City is named after him; the Grolier Club is a sufficiently major institution to have its own librarian. I figured the club must keep track of all the known Grolier bindings, so I dropped them an inquiry. Yes, came the reply, they could tell me where the copy of Copernicus' book was if it were genuine, but as for fakes, I should ask Howard Nixon, former keeper of rare books at the British Museum.

I still treasure the reply from Nixon, who was then librarian at Westminster Abbey. "It is very nice to be asked a question that one can answer so easily," he wrote, and he told me that the binding reposed safely at the Victoria and Albert Museum in South Kensington, London. The binding was one of a number made by the French forger Louis Hague. Many of these forgeries had been sold by the reputable London firm of Bernard Quaritch to a nineteenth-century English collector, John Blacker. Even after Quaritch became suspicious of the bindings, Blacker refused to believe they were false.

In due time I made the pilgrimage to the V & A, a magnificent museum of decorative arts of all ages. The Copernicus volume, too, was a showy sample of decorative arts, its splendid binding as fake as a three-dollar bill, and its genuine old bookplates equally fraudulent in their placement in this particular copy. At least there were no anonymous annotations whose source might have been destroyed by the nineteenth-century rebinding scam.

The V & A copy is unique in the census with its deliberate fake binding. Many copies have been rebound, of course, to replace shabby or tattered covers, without any intention to fool anyone. On the market, copies in original bindings in good condition fetch a higher price than those rebound, so an owner always faces a dilemma in replacing an old but dilapidated binding. Occasionally I have encountered disgusting cases of modern library-buckram, but more frequently tasteful imitations of earlier binding styles, though never undertaken with the goal to mislead a naive collector. There is a sort of intermediate situation, however, when an old binding has been transferred from another book. Cognoscenti call this a remboitage*and when it is recognized, it definitely lowers the value of the book compared to a copy with a comparable original binding.

WITH SO MUCH indirect experience with book auctions, I finally decided I should see one for myself. So after the manuscript of the Census had been sent off for publication, I resolved to go to a Sotheby's auction to observe a De revolutionibus on the block. Accordingly, early on the morning of 16 November 2001 I flew to New York for the sale of the Friedman collection.

The collector, Meyer Friedman of San Francisco, was the medical doctor who made famous the concept of Type A and Type B personalities. He demonstrated not only that certain personality traits correlated with higher risk for heart attacks, but that by working to suppress some of the pushy or aggressive behavior, Type A persons could actually reduce their chances of having a heart attack. As a collector Dr. Friedman acquired the great medical titles, such as Andreas Vesalius' De humani corporis fabrica (1543), the great illustrated anatomy text, and William Harvey's much rarer De motu cordis (1628), the first correct analysis of the circulation of the blood. But his collection also included pure science works as well, including those by Copernicus, Newton, and Einstein.

The fake Grolier binding on the De revolutionibus in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

I never met Dr. Friedman because I had already seen his copy of Copernicus' book when it was still in the hands of its previous owner, Marcel Chatillon, a French surgeon. Chatillon practiced in the former French colony of Guadeloupe, and he collected regional art and Americana. De revolutionibus fell in the latter category because Copernicus mentioned America, "named after the sea captain who discovered it." The Polish astronomer was misled on this matter because he relied on Martin Waldseemiiller's Cosmographia introductio of 1509 for news about the New World, but nevertheless his fleeting reference to Amerigo Vespucci was enough to qualify his book as an Americanum.

Dr. Chatillon showed me his copy in Paris. I still cringe whenever I recall our conversation: Chatillon spoke no English, and my spoken French could charitably be called rudimentary. Nevertheless, I heroically carried on in French as I examined his relatively ordinary copy, measuring its page size, noting the binding and the position of the errata leaf, and hastily scanning for annotations. As it turns out, I missed the two minor marginal notes and failed to investigate carefully the most interesting point in the book, its somewhat weathered final leaf.

In 1978 Dr. Chatillon sold his Copernicus copy, and it went into the Friedman collection. When Dr. Friedman acquired it, a first edition was still relatively easy to find, and he got the book for 365,000. During the 1970s and 1980s twenty copies passed through the market, but ten of them moved to institutional libraries, gradually contracting the number of copies available for private owners. By 2001, when Sotheby's announced the Meyer Friedman sale, only about twenty copies remained in private collections, and with the rise in cyber fortunes owned by the newly wealthy with interests in science and technology, the competition to obtain a copy had built to volcanic proportions.

The austerely elegant auction room at Sotheby's took me by surprise. There was not a book in sight apart from the sale catalogs carried by the potential buyers, a group of twenty-five who were mostly dealers. I recognized several from London and others from the West Coast. On a raised dais along the side and front were nine phone stations for anonymous bidders, and in the back was a long table with computers, whose operators apparently controlled a screen in the front that would show the lot number and current bid in ten different currencies. As the group assembled, I introduced myself to Selby Kiffer, one of the Sotheby experts, who promptly asked if I wanted to see the Copernicus. Indeed I did, so he fetched it from the back room.

Several dealers gathered around as I reacquainted myself with the book. I took a hard look at the last leaf, a bit scruffy with a library stamp totally removed and carefully patched with a paper repair. Clearly, the leaf had been remounted, but I saw no reason to doubt its legitimacy in the volume. I turned the book back to Kiffer and settled down in one of the hundred portable chairs whose rows formed a square in the middle of the room. The clerks took their places behind the phones. David Redden, the auctioneer, ascended the spotlighted podium in the front and asked, "Shall we begin?"

The bidding on various lots moved sequentially and swiftly, by standard increments, $ 25 for the lower range, for example, or $ 500 when the bids got over $ 5,000. There was no accidental bidding by someone scratching his nose—even the catalog made that explicit. Bidders held up their hands, and Redden frequently indicated who had the current bid, with a phrase such as "in the third row" or "Selby's phone." Otherwise the auctioneer limited himself to the figures—the lot numbers, which came at a rate of about one a minute, and the bids. It was very rare that he announced the author or title on the block.

By the time the sale approached lot number 34, the De revolutionibus, the assembled dealers realized, with some shock and even more curiosity, that about 80 percent of the books were being snatched up by an anonymous telephone bidder, designated as L020, and most of the others were going, after a duel of phones, to a second anonymous bidder, L029. Several of the rarer items had already gone well above the high end of the estimated bids.

The auction had been under way barely half an hour when lot number 34 flashed on the screen. I set my stopwatch. Did the bidding start at $100,000 or $200,000? I was too excited to remember, but the auctioneers say it was $150,000.1 was later sorry that I hadn't registered for one of the numbered bidding paddles so that I could have made the first offer, even though I would have had to mortgage the house to back it up. The bids came from the floor at a furious rate, notching up by $25,000 intervals. At first the bids came too rapidly for the phone bank to compete, until the offers passed the high estimate of $400,000—elapsed time, forty-five seconds. The highest floor bid came in at $550,000, already past the previous auction record for a first edition of De revolutionibus, and then the battle devolved to three anonymous phones. I could overhear a Sotheby's representative say, "It's now at $600,000. Do you want to raise?" And L020 raised.

Moments later, the bidding stopped. The auctioneer tapped the hammer at $675,000. With Sotheby's hammer fee, the book had cost L020 almost exactly $750,000.1 clicked my stopwatch. The bidding had taken two minutes and sixteen seconds.

The sense of curiosity in the room was palpable. Who were these mystery bidders? The rest of the auction gave only limited clues. The initial printing of a thousand copies of Darwin's On the Origin of Species had sold out on the first day, but the edition is not particularly rare and Sotheby's high estimate of #35,000 was entirely reasonable. Nevertheless, the two telephone duelists drove the price to a sublimely ridiculous $150,000. Experienced collectors would have already owned this classic, and no institution could have been so reckless with its funds. Clearly, the two collectors were beginners, going after an instant library, keenly chasing both the medical and the more strictly scientific items.

In the auction's aftermath there was a great deal of speculation, and no hard facts, about the identity of the well-heeled buyers. And there was a lot of second-guessing about the status of the Copernicus book itself. "There is a real problem about that last leaf," Rick Watson assured me. A longtime and well-trusted friend among the London book dealers, Rick had noticed that the chain lines on the leaf did not run parallel with the edges of the printing, a detail that had escaped my inspection. Since the conjugate leaf was not skewed in the printing, the final leaf had to have come from somewhere else. Clearly, it was a sophisticated copy.

I checked my records again. The book had been auctioned at Drouot in 1973, and sure enough, it lacked the last leaf. Had it passed through Scheler's shop? The team that added a fake water stain in the Cal Tech copy could have fabricated a page with a fake patch to cover a phony library stamp. That would be enough to keep almost anyone from looking too hard at the page. To my eyes the leaf passed muster; it was similar to a number of copies I had seen in which the wear and tear on the first and last pages was relatively harsh. My notes showed that the Scheler shop formerly had two copies in which the last leaf was probably in facsimile. The genuine leaf in the Chatillon-Friedman copy could have come from one of those Parisian copies. Someday, no doubt, their owners' names will become known. Then I would certainly relish the chance to inspect any of those copies more thoroughly.

Meanwhile, there are several collectors impatiently waiting to spend a million dollars on an unsophisticated first edition of Copernicus' book in an original sixteenth-century binding—preferably a copy with a known provenance and clear title.

* Nor a great contribution to letters, nor a very sound translation, this publication was Copernicus' way to learn Greek.

† Posner told me that many years earlier he had been shown a novelty, a small neon bulb. "That gives bright light," he said. "What are you going to use it for?" He was told it worked just fine for testing automobile spark coils, but his bright idea was to make neon advertising signs. He remarked that Pittsburgh had some of the oldest neon signs in existence because in the early days the anodes were made of heavy plarinum. With his resulting fortune he was able to acquire a formidable collection of rare books.

* Ir would be pleasant to think that the P stood for the printer's name, Petreius, but P is such a common watermark that experts believe it simply stands for Papier, the German or French word for paper.

* A French word meaning more generally something placed into a socket.