In the News

News disseminated through multiple mediated platforms, (print, television, online) is indeed a part of popular culture. Issues, people, and events brought to the public’s attention through the media pervade a society and influence what we know and how we think. Journalism is a venue for the circulation of ideas and knowledge. Just like other channels of popular culture, such as literature and film, news media tell the stories of our lives as well as our dreams and desires. This anthology focuses on women who found themselves in news headlines and became important parts of the ongoing and evolving dialogue about women’s roles and women’s rights in the United States.

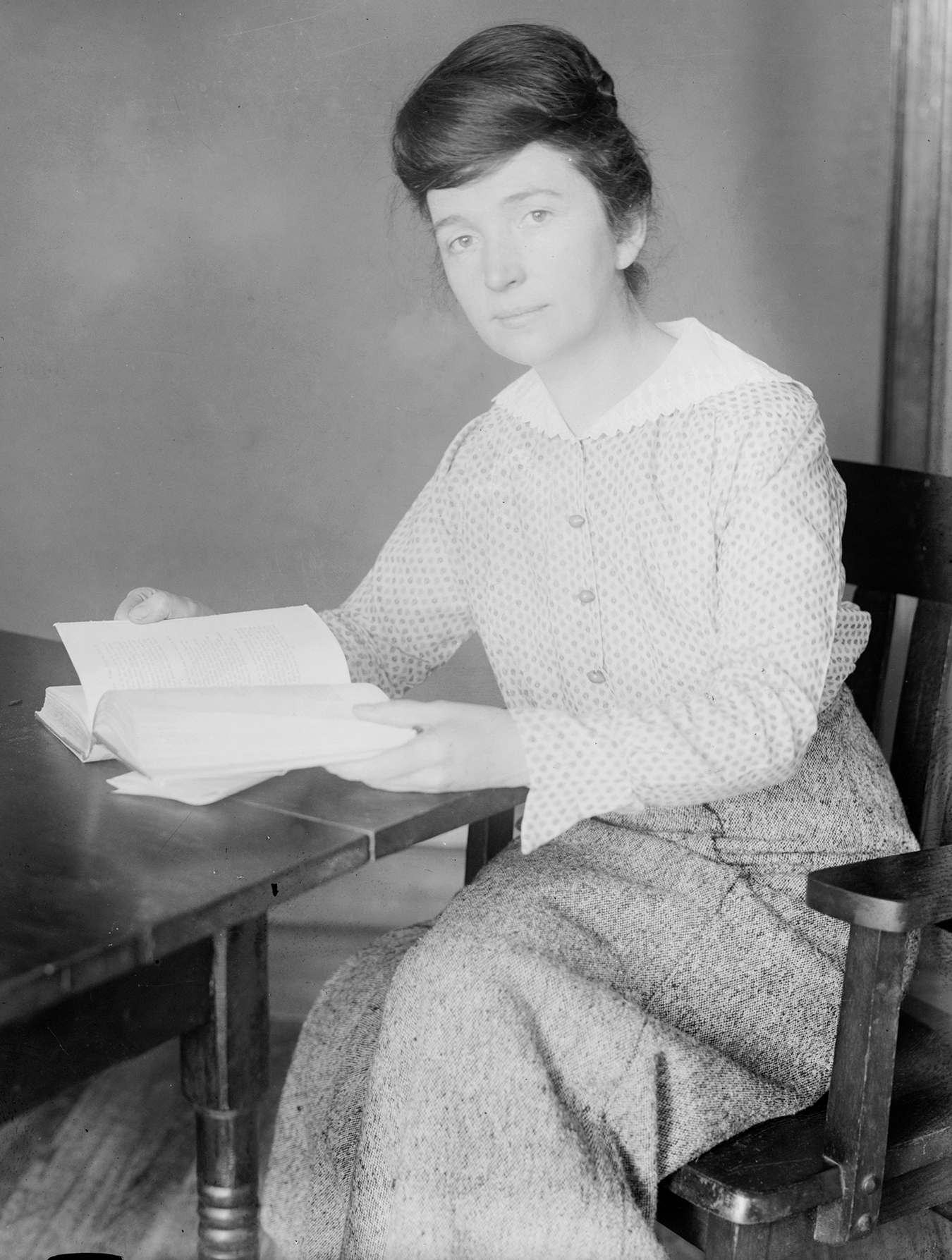

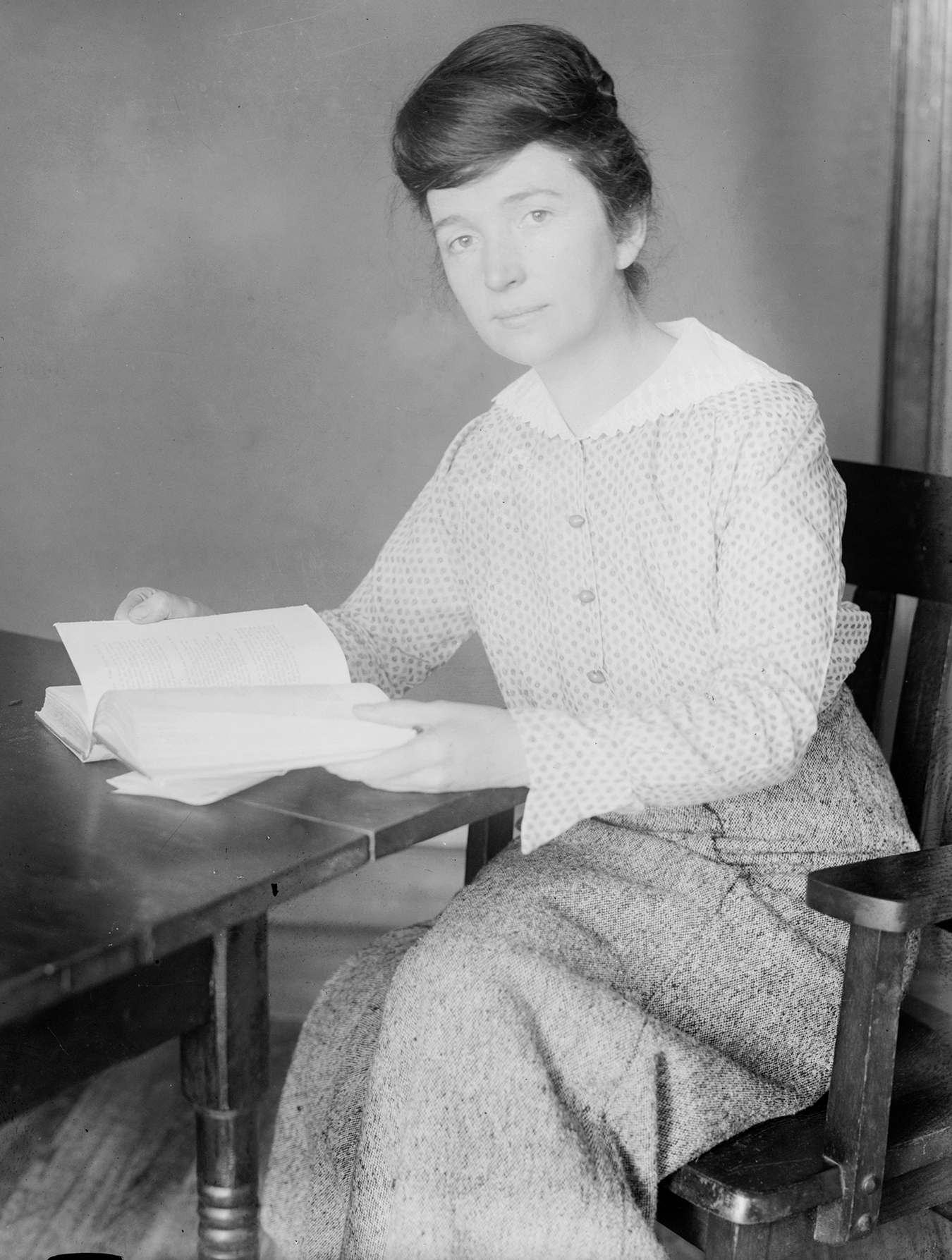

Margaret Sanger fought for the most fundamental of women’s rights—the right to one’s body. For Sanger, control over reproduction was a revolutionary act, with the potential for women’s personal and political liberation. However, it remains uncertain in whose interests this revolution was waged. Was Sanger pushing for a personal right of reproduction, or was she working for political population control? Controversy permeates Sanger’s life, and despite the layers of complexities her life reveals, she continues to be a cultural icon of the feminist movement.

Sanger saw her personal experience as connected with a political cause that deeply impacted other women. Sanger’s commitment to birth control—a term she coined—was influenced by her mother’s early death following 18 pregnancies and 11 live births. Additionally, as a nurse, Sanger met women living in poverty who, recovering from multiple pregnancies, were desperate for contraceptive information. Her activism led to the opening of the nation’s first birth control clinic in 1916, which drew a crowd of 400 women. But this action quickly resulted in her arrest for causing a public nuisance, and the closure of the clinic.

Activist Margaret Sanger popularized the term “birth control” as an advocate for women’s health. The clinic she opened evolved into what is now known as Planned Parenthood. (Courtesy of the George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress)

Sanger would later go on to establish the first legal birth control clinics in the United States. In 1921, she founded the American Birth Control League, which would later become the Planned Parenthood Federation. During World War II, Sanger focused her efforts on international birth control, helping to found the International Planned Parenthood Federation. Finally, in the 1950s she played an important role in the development of the birth control pill.

Sanger began her crusade for birth control by working closely with the Socialist party, militant working-class groups, and the anarchist movement. However, Sanger’s alliance with radical feminist causes would not be long lasting. Influenced by population control advocates and eugenicists, her birth control movement was robbed of its progressive possibilities as Sanger repositioned her work to align with mainstream conservative efforts. Sanger linked the devastating effects of poverty to uncontrolled population growth, which led many to assume that birth control was the duty, rather than the right, of the poor.

The nuances of Sanger’s life and her work are to be found in her letters, journals, articles, and speeches. These sources reveal her struggles to find balance within and without amid her all-consuming fight for women’s freedom. Before Sanger’s death in 1966, she saw the Supreme Court make birth control legal for married couples in Griswold v. Connecticut. The progressive possibilities of birth control ignited by Sanger remain, and she leaves a legacy that continues to be disputed today.

Stephanie Leo Hudson

See also: Planned Parenthood.

FURTHER READING

Davis, Angela. 1981. “Racism, Birth Control and Reproductive Rights.” In Women, Race and Class, 202–21. New York: Random House.

The Margaret Sanger Papers Project. New York University, https://www.nyu.edu/projects/sanger/.

Sanger, Alexander. 2007. “Eugenics, Race, and Margaret Sanger Revisited: Reproductive Freedom for All?” Hypatia, 22: 210–17.

Sanger, Margaret. 2003. The Selected Papers of Margaret Sanger, Volume 1: The Woman Rebel, 1900–1928. Edited by Esther Katz. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Sanger, Margaret. 2006. The Selected Papers of Margaret Sanger, Volume 2: Birth Control Comes of Age, 1928–1939. Edited by Esther Katz. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Sanger, Margaret. 2010. The Selected Papers of Margaret Sanger, Volume 3: The Politics of Planned Parenthood, 1939–1966. Edited by Esther Katz. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Steinem, Gloria. 1998. “Margaret Sanger.” Time Magazine, April 13.

Fannie Lou Hamer was the youngest of 20 children born to Mississippi sharecroppers Jim and Ella Townsend. At age 44, she immersed herself in the Civil Rights Movement and quickly emerged as a leader. The model of the passionate layperson who lived the inequities that propelled the grassroots movement, Hamer became well known for saying, “All my life I’ve been sick and tired. Now I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired” (Mills, 1996: 93). She was a rhetorically savvy speaker who remains a symbol of the Civil Rights Movement.

Hamer lived in poverty in a racially segregated community, began picking cotton at the age of six, and left school after sixth grade to support her family. She married Perry Hamer in 1944 and set up house on a plantation near Ruleville, Mississippi. She was known by community members for her singing, work ethic, and knowledge of the Bible and the U.S. Constitution. After undergoing surgery to remove a small uterine tumor, she discovered that the doctor had performed an unauthorized hysterectomy. Later she learned that thousands of poor, rural black women were sterilized without consent at that time. By 1962, Hamer had experienced a lifetime of mistreatment born out of institutionalized racism. When the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) visited Ruleville that summer to encourage blacks to register to vote, Hamer was persuaded.

It did not take long for other civil rights champions to recognize that Hamer could be an instrumental participant in the movement. She was intelligent and persistent. She unified and inspired others with her singing. She embodied the movement leaders’ claims that ordinary people can work for social change. She shared her stories with honesty and power. She explained her understanding of the intersections of race, economic power, and political efficacy. She did not hesitate to publicly denounce leaders, mimic public officials, or berate audience members who were not engaged in the movement. At the 1964 Democratic National Committee, she spoke as a representative of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, exposing the brutality of life in Mississippi to a nation largely oblivious to the injustices in that state. She gained the attention of the nation.

Hamer’s work was arduous. In 1963, she was jailed and beaten. She unsuccessfully ran for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1964 and Mississippi State Senate in 1971. Her work was all consuming: mentoring young people, traveling, and speaking with the purpose of gaining equal rights for black citizens. Visiting hostile communities made her work occasionally dangerous. She acknowledged the stress her work put on herself and her family but said, “Although we have suffered greatly, I feel that we have not suffered in vain. I am determined to become a first-class citizen” (Mills, 1996: 79).

In her later years, she went on speaking tours, focused on poverty as a social ill, and was embraced by second-wave feminists who turned to her for insight about how to resist sexism. She developed a strong relationship with citizens in Madison, Wisconsin, who supported her efforts to start a farm cooperative in Mississippi. Due to untreated cancer, hypertension, and diabetes, Hamer’s health declined rapidly in her last year of life. Still, she traveled and spoke. She died at age 59, known then and now as a warrior for civil rights.

Lori Walters-Kramer

FURTHER READING

Brooks, Maegan Parker. 2014. A Voice that Could Stir an Army: Fannie Lou Hamer and the Rhetoric of the Black Freedom Movement. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

Brooks, Maegan Parker, and Davis W. Houck, eds. 2011. The Speeches of Fannie Lou Hamer: To Tell It Like It Is. Normal, IL: Illinois State University.

Lee, Chana Kai. 1999. For Freedom’s Sake: The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois.

Mills, Kay. 1993. This Little Light of Mine: The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer. New York: Plume.

Famous for asking blunt questions of famous men, Helen Thomas was one of the most well-known journalists in American history (1920–2013). As a White House correspondent, she reported the news about every president from John F. Kennedy to Barack Obama. During her career, Thomas overcame barriers of gender discrimination in the media industry and championed the watchdog role of the press in a democratic society. Thomas took pride in the American tradition of free speech that allows reporters to ask leaders difficult questions and hold them accountable to the people. Reporters are “guardians of the people’s right to know,” she wrote (2006, 201).

Thomas began her career as a reporter as men left to fight World War II, leaving behind jobs that had previously excluded women. She became a reporter in Washington, D.C., in 1958 and invented her high-profile position reporting on the president by simply showing up at the White House and refusing to leave.

Thomas became a reporter at a time when women were allowed to write lightweight stories for the “society pages,” but not about topics like politics. The National Press Club, an elite club for reporters, where important people often gave speeches, was an exclusive men’s club until 1971. Thomas became the first female president of the club in 1975. She was also the first woman recipient of the National Press Club’s Fourth Estate Award, previously given to journalism superstars like Walter Cronkite.

Thomas lamented the rise of “news management” strategies that presidents use to control what the public knows about government policy. She felt strongly that reporters must remain skeptical of what presidents say, and have the courage to ask tough questions to get complete information for the public. Thomas argued that the news media have often failed to challenge falsehoods. The foremost example is the Iraq War. President George W. Bush claimed that Iraq supported the terrorist group Al Qaeda that attacked the United States in 2001. Bush also claimed Iraq threatened the United States with weapons of mass destruction. Although eventually proved false, these claims were effective in manipulating public opinion to support the American invasion of Iraq in 2003. The media generally failed to question the president’s faulty reasoning and instead became what Thomas called “an echo chamber for White House pronouncements” (Thomas, 2006: 136).

Thomas’s White House career ended abruptly in 2010 after she commented at a White House event that Israelis should stop occupying Palestinian land and go back to other countries in Europe and the United States. As a child of Lebanese parents, Thomas was well informed of Middle Eastern issues. She sympathized with the Palestinian experience in the conflict between Jewish Israel and Arab Palestine, in which Israel controls Palestinians in the West Bank with a military occupation. After her controversial remarks, she was accused of anti-Semitism. The backlash became so powerful that she was forced to resign her job as a columnist with Hearst Newspapers. For some scholars of news media, the political backlash Thomas received is evidence of the one-sidedness of the debate over Israel and Palestine in the United States. It was an ironic career ending for a woman who had devoted her life to free speech. Thomas died in 2013.

Dylan Bennett

FURTHER READING

Thomas, Helen. 1999. Front Row at the White House: My Life and Times. New York: Scribner.

Thomas, Helen. 2006. Watchdogs of Democracy? The Waning Washington Press Corps and How It Has Failed the Public. New York: Scribner.

Betty Friedan’s complex legacy for antisexist activists and students of feminist studies begins with her iconic work, The Feminine Mystique, published in 1963 to wide acclaim, popularity, and opposition. The book has often been credited with catalyzing the second-wave feminist movement, in which Friedan was a major figure and leader (she served as cofounder of the National Organization for Women [NOW], the National Women’s Political Caucus, and the National Abortion and Reproductive Rights Action League [NARAL]). In The Feminine Mystique, she famously articulated “the problem that has no name,” the condition of middle-class women in the United States at mid-century: this narrative revolves around the iconic figure of the (well-educated) housewife who, having sacrificed her potential career to support a husband and raise children, was left depressed and isolated, divorced in mid-life, and was struck with the impossibility of empowerment in the public sphere. Friedan’s vision of liberation for the home-based reproductive laborer electrified many women who participated in feminist movements. But its exclusion of women whose lives and experiences of sexism did not fit this model has been the cause for further feminist theory and organizing. For instance, during the early formation of NOW, Friedan expressed horror at the presence and power of lesbians and lesbian politics in feminist networks, fearing that a movement focused on sex and sexual orientation would be the subject of ridicule. Her naming of lesbians as a “lavender menace” within feminism sparked outrage—and inspired a lesbian feminist organization, the Lavender Menace.

Friedan defined herself as an “equality” feminist for whom the passage of the ERA, equal pay legislation, and abortion access were the most natural and important movement goals. But her work was critiqued and opposed by those who understood their own identities (including intersectional notions of their identities as women) to be inextricable from structures of race, class, and nation—as well as gender/sex/sexuality. Friedan provided a foil for feminisms of color, working-class, socialist, anticolonial, and antiracist feminisms because she installed the white, well-educated, middle-class U.S. citizen woman as the privileged subject of feminism. Black feminist theorist bell hooks’s 1984 Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center opens with a searing critique of Friedan’s promotion of white, middle-class normativity as the basis of the feminist subject. For hooks, Friedan’s importance to feminism dangerously marginalized working-class women who could never be “liberated” through exclusive focus on the realm of the private household, as it was not their (singular) site of oppression. As hooks argues, this model fails to account for working-class women who would be called on to perform the childcare and associated reproductive labor left behind by the liberated housewife who became a professional-class worker in a continually exploitative capitalist society.

Beginning in the 1970s, Friedan became an international activist focused on an “equal rights” agenda. As she and her fellow NOW members insisted, the problem of women’s oppression was a part of, not an addendum to, other sociopolitical problems in need of radical reconfiguration. Paradoxically, in her work at the UN Conferences on Women, Friedan used this position to mobilize an essentialist notion of a “sisterhood” in which the realm of (public) “politics” would be sidelined in favor of a decontextualized focus on “women’s issues.” Friedan promoted policies that would influence the status of women across the globe; she also lauded U.S. feminism as an example for others, dismissing the contrary possibility that feminist movements in socialist or anticolonial formations might provide a model or partner for “first-world” feminists. Her legacy exemplifies both the power of an equal rights discourse and also white, liberal feminism’s self-installation as the paradigmatic definition of feminism.

Brooke Lober

See also: Women’s Liberation Movement.

FURTHER READING

Declaration of Mexico on the Equality of Women and Their Contribution to Development and Peace. 1975. Adopted at the World Conference of the International Women’s Year, Mexico City, Mexico. June 19–July 2.

Friedan, Betty. 1963. The Feminine Mystique. New York: W.W. Norton.

Friedan, Betty. 1976. It Changed My Life: Writing on the Women’s Movement. New York: Random House.

hooks, bell. 1984. Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center. Boston, MA: South End Press.

Shirley Chisholm challenged the status quo and advocated for the marginalized before, during, and after her political career. New York City residents elected her to the State Assembly in 1964. In 1968, she became the first black woman to be elected to the United States Congress. She ran for the presidency as a Democrat in 1972—the first woman to ever do so. The titles of her autobiographies, Unbought and Unbossed and The Good Fight, echo her tenacious approach to political office.

Chisholm’s father encouraged her to see the beauty of her blackness; her mother instilled Christian values in her. As a child she was unafraid to speak her mind, and as an undergraduate she honed her speaking skills on the debate team at Brooklyn College. She was active in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the League of Women Voters while attending Columbia University, where she earned a master’s degree in elementary education.

Chisholm’s political career spanned 18 years. Throughout, she concentrated on issues of concern in the black community and promoted programs to eradicate discrimination. At the 1972 Democratic National Convention, she declared her candidacy for president, knowing she had little chance to be chosen as the party’s nominee. She later explained, “I ran because someone had to do it first,” so that future women and non-whites would be regarded as serious candidates (Chisholm, 1973: 3). After the 1972 election she remained in Congress, serving seven terms for Brooklyn’s 12th Congressional District, until 1982.

Chisholm was an impressive speaker. In the midst of the Vietnam War, she delivered her first speech as a member of Congress, where she proclaimed her decision to vote against any bill to fund the Department of Defense. Her speech attracted the attention of student groups, resulting in more than 100 visits to colleges where she was regularly encouraged to run for president. One of her better-known speeches was delivered to the House of Representatives. In it, she backed the Equal Rights Amendment and developed her thesis that “artificial distinctions between persons must be wiped out of the law” (Chisholm, 1970). Her campaign speeches often centered on economic justice for women and revealed her outrage at the discrepancy between men and women’s salaries as well as the paucity of professional opportunities for women. She understood the intersectionality of race and sex. In one speech she asserted that “[t]he black woman lives in a society that discriminates against her on two counts. The black woman cannot be discussed in the same context as her Caucasian counterpart because of the twin jeopardy of race and sex which operates against her, and the psychological and political consequences which attend them” (Chisholm, 1974).

One of Chisholm’s most controversial actions during her tenure in Congress was her visit to George Wallace, a political opponent and segregationist, in the hospital after an assassination attempt. She confided to him, “You and I don’t agree, but you’ve been shot, and I might be shot, and we are both children of American democracy, so I wanted to come and see you” (Chisholm, 1973: 97). The controversy perplexed her and is one reason why, when she left office, she claimed she was often misunderstood.

Chisholm retired to Florida before her death in 2005. She continues to be known for her commitment to democratic ideals, social and economic justice, and living her life with integrity and courage.

Lori Walters-Kramer

FURTHER READING

Chisholm, Shirley. 1974. “The Black Woman in Contemporary America.” America Radio Works. http://americanradioworks.publicradio.org/features/sayitplain/schisholm.html.

Chisholm, Shirley. 1973. The Good Fight. New York: Harper & Row.

Chisholm, Shirley. 1970. “For the Equal Rights Amendment.” American Rhetoric. http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/shirleychisholmequalrights.htm.

Chisholm, Shirley. 1970. Unbought and Unbossed. New York: Avon.

Dolores Huerta is best known for her long career as a labor organizer and cofounder of the United Farm Workers union (UFW) alongside César Chávez (1927–1993). Though not as well known as many male leaders of the Civil Rights era, Huerta has been a powerful change agent for Mexican American men, women, and children laboring long hours in pesticide-rich fields and with little access to breaks, food, toilets, or shade.

Huerta was born in New Mexico to a father who worked as a coal miner, farm worker, and union activist before his election to the New Mexico state legislature. Although her father’s activism influenced her, Huerta’s parents divorced when she was young, and she was raised by her mother in Stockton, California. Huerta’s mother was a cannery worker, waitress, and eventual owner of a restaurant and hotel; she modeled how a woman could make a public life for herself beyond the domestic space of the home and traditional motherhood. Huerta raised 11 children of her own, and her difficult experiences as both a mother and a woman in the fields provided insights into the gendered nature of farm worker’s oppression. She raised awareness about sexual harassment, the impact of pesticides on women’s bodies, and the need for women’s leadership in unions and in government.

Huerta’s influence in the UFW could be seen in the Delano grape pickers’ strike (1965) and the coalitions she formed between strikers and consumers in the nationwide grape boycotts (1968–1969). In addition to organizing workers, Huerta sought political reform. She participated in voter registration campaigns and lobbied the federal and California state governments for the Aid to Dependent Children Bill (1963) and the Agricultural Labor Relations Act (1975); the latter act protected the collective bargaining rights of farm workers and established a board to review workers’ grievances. She also advocated for stricter controls on pesticides known to be dangerous and sought improved public services, including health care access and bilingual driver’s license exams.

After the success of the boycotts, Huerta became the first woman and Chicana/o to negotiate with the growers. As an outspoken Mexican American woman, she violated cultural expectations of submissiveness and domesticity, and as such she earned a number of nicknames, including la pasionara (“the passionate one”); soldadera (referencing women in the Mexican Revolution); and “dragon lady,” given to her by opposing landowners. Huerta is unapologetic for her controversial negotiating style: “Why do we need to be polite to people who are making racist statements at the table, or making sexist comments?” (Chávez, 2005: 249).

In addition to her role in the UFW, Huerta cofounded the Coalition of Labor Union Women (1974), serves on the board of the Feminist Majority Foundation, campaigns on behalf of women seeking public office, and speaks on issues of social justice and public policy as the president of the Dolores Huerta Foundation. In recent years, she has been recognized for her diverse contributions for social, economic, and environment justice, and in 2011 she received the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Christina Holmes

FURTHER READING

Chávez, Alicia. 2005. “Dolores Huerta and the United Farm Workers.” In Latina Legacies, 240–54. Edited by Vicki Ruiz and Virginia Sanchez Korrol. New York: Oxford University Press.

Dolores Huerta Foundation. http://doloreshuerta.org/.

García, Mario T., ed. 2008. A Dolores Huerta Reader. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Ruiz, Vicky. 1998. From Out of the Shadows: Mexican Women in Twentieth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press.

Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was the second woman ever to serve on the Supreme Court. Since graduating from law school in 1959, Ginsburg has fought for women’s legal rights and equal protection under the law during her expansive career as a lawyer, a professor, and a judge.

Joan Ruth Bader was born on March 15, 1933, in Brooklyn, New York. Her mother, who died just before Ginsburg’s high school graduation, taught her to value learning and encouraged her to invest in her education. She took her mother’s encouragement to heart and studied government at Cornell University, graduating first among the women in her class. She married Martin Ginsburg right after graduation, and they both decided to pursue careers in law.

She enrolled in Harvard Law School with her husband, where she was one of nine women in a class of more than 500 students. She faced discrimination based on her gender while in law school—one Harvard dean asked her to justify taking the place where a man could be (Scanlon, 1999: 120). Despite such expressions of hostility and skepticism toward her, she was elected as the editor of the Harvard Law Review. After her husband graduated from Harvard and began work at a law firm in New York City, she transferred to Columbia Law School, where she tied for the top position in her graduating class.

Ginsburg struggled to find a job, despite her impressive performance in law school. She later said that “her status as ‘a woman, a Jew, and a mother to boot’ was ‘a bit much’ for prospective employers in those days” (Cushman, 2013: 487). She was eventually hired as a law clerk with a district court judge in New York, then went on to become the second woman to teach law at Rutgers University. Later, she became the first tenured woman law professor at the Columbia Law School.

Ginsburg did not become a lawyer intending to advance women’s rights. However, after reading Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex in the early 1960s, she realized that much of the injustice she faced in her life was due to structural gender discrimination in American society, based on harmful gender stereotypes. She came to believe that the legal system should be a tool in fixing those inequalities.

In 1972, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) established the Women’s Rights Project and asked Ginsburg to lead its efforts. Over the next four years, she brought six gender discrimination cases to the Supreme Court and won five of them. Significantly, she fought for a heightened standard of review in gender discrimination cases, and finally won it in 1976, effectively establishing a legal framework for women’s equality to men.

In 1980, President Jimmy Carter appointed her to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. As a judge, she became known for her careful attention to detail and sensitivity to the fact that her decisions would affect real lives. She served on the U.S. Court of Appeals for 13 years and wrote more than 300 opinions that dealt with abortion rights, gay rights, and affirmative action. In 1993, President Bill Clinton nominated Ginsburg to serve on the Supreme Court. The Senate confirmed her with a 97–3 vote, and she was sworn in on August 10, 1993.

In 2014, she wrote the dissenting opinion in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores Inc. The decision allowed closely held for-profit companies to refuse to include birth control in employees’ health insurance plans. Instantly, Ginsburg’s sharp dissent became an Internet sensation—especially after then-law student Shana Knizhnik started a Tumblr account called “Notorious R.B.G.”—a reference to popular hip-hop artist Notorious B.I.G. The account became a “virtual shrine” to Ginsburg (Rand, 2015: 80) and turned her into a feminist icon.

Ginsburg’s legal career has spanned more than 55 years. Over that time, she has helped create new legal precedent for equal protection for both men and women under the law and has become one of the most influential legal voices for women’s rights.

Maggie Monson

FURTHER READING

Cushman, Clare, ed. 2013. The Supreme Court Justices, Illustrated Biographies, 1789–2012, 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: CQ Press.

Rand, Erin J. 2015. “Fear the Frill: Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the Uncertain Futurity of Feminist Judicial Dissent.” Quarterly Journal of Speech, 101(1): 72–84.

Scanlon, Jennifer, ed. 1999. Significant Contemporary American Feminists: A Biographical Sourcebook. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Gloria Steinem is an internationally acclaimed journalist and feminist. She studied government at Smith College and graduated Phi Beta Kappa. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, she served as director of the Independent Research Service, an organization funded in secret by the CIA (1976). In 1960, Esquire offered Steinem her first journalistic assignment, a story on the issue of contraception. Steinem’s 1962 “Moral Disarmament” article, concerning the pressure women face to choose between marriage and a career, was published a year before Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique. In 1963, Steinem worked undercover as a Playboy Bunny to expose the sexism employees faced at the New York Playboy Club. After the article “A Bunny’s Tale” was published (accompanied by a photo of Steinem in costume), Steinem struggled to secure other assignments. Ironically, because she had appeared in print as a sex object, she was dismissed as too sexual to be taken seriously. Steinem persevered, however, and eventually secured journalistic success, cofounding the feminist magazine Ms. in 1972 (Outrageous, 1983: 74).

Today, Steinem is best recognized for her longstanding activism for women’s rights, including abortion. In 1969, she covered an abortion speak-out for New York Magazine and felt what she called a “big click” (Pogrebin, 2011). Steinem had terminated a pregnancy at 22 and wished to help other American women secure safe and legal abortions without shame. Her fight for reproductive rights remains controversial today. When, for example, Steinem was interviewed by Land’s End for their March 2016 feature, “Legends,” anti-choice consumers expressed outrage. The clothing company promptly removed Steinem’s interview from their website—a response that then angered pro-choice shoppers, who considered the decision an affront to women’s rights. (Significantly, the interview did not address abortion. Steinem spoke instead for the need for an Equal Rights Amendment to secure gender equity) (Bukszpan, 2016).

Although abortion remains a central concern, Steinem has also campaigned for the Equal Rights Amendment, testifying before the 1970 Senate Judiciary in its favor. She also has raised awareness about the damage pornography poses to women and the endemic of female genital cutting, in such books as Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions (1983), as well as in countless speeches, interviews, articles, and public appearances. Steinem advocated for same-sex marriage as early as 1970. Although she long rejected heterosexual marriage as oppressive to women, in 2000 she married David Bale at the home of Wilma Mankiller, the first woman principal chief of the Cherokee Nation. (Bale succumbed to cancer in 2003.)

Steinem has also forged lasting connections with other feminist leaders, notably Bella Abzug, an American lawyer who, alongside Steinem and Friedan, founded the National Women’s Political Caucus. Today, Steinem continues to champion this collaborative spirit. When asked in a 2016 interview what advice she had for young feminists, Steinem emphasized: “Don’t worry about what you should do; do whatever you can. And seek companions with shared values. If we’re isolated, we come to feel powerless when we’re not.”

Some feminists critique Steinem for a white and cisgender focus, suggesting that she conflates “feminism” with the aims of white and straight women, excluding women of color and transwomen from her purview (Grey, 2016). In 2016, Steinem again stirred controversy when, in an interview with Bill Maher, she characterized young women who supported presidential candidate Bernie Sanders over Hillary Clinton as boy-crazy, remarking: “When you’re young, you’re thinking, ‘Where are the boys? The boys are with Bernie.’ ” Later, Steinem claimed her words had been “misinterpreted.”

In 1993, Steinem was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York. Despite occasional mishaps and accusations of exclusionism, she remains at the forefront of the women’s movement today.

Eden Elizabeth Wales Freedman

See also: Ms. Magazine; Women’s Liberation Movement.

FURTHER READING

Bukszpan, Daniel. 2016. “How Land’s End Suddenly Became an Abortion Battleground.” Fortune. February 26.

Grey, Sarah. 2016. “An Open Letter to Gloria Steinem on Intersectional Feminism.” The Establishment, February 8.

Harrington, Stephanie. 1976. “It Changed My Life.” The New York Times, July 4.

Marcello, Patricia. 2004. Gloria Steinem: A Biography. Westport: Greenwood.

Pogrebin, Abigail. 2011. “How Do You Spell Ms.” New York, October. http://nymag.com/news/features/ms-magazine-2011-11/.

Steinem, Gloria. 1983. Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions. New York: Holt.

Steinem, Gloria. 2015. My Life on the Road. New York: Random House.

GERALDINE A. FERRARO (1935–2011)

Geraldine A. Ferraro was an esteemed trailblazer for women in American politics and held numerous political positions from the 1970s until her death in 2011. She was the first woman and first Italian American in American history to be nominated by a major political party (Democratic Party), as a candidate for national office. In the 1984 presidential election, Ferraro campaigned with Walter Mondale to be vice president and president, respectively. Many credit Ferraro’s candidacy as shifting the political and social landscapes in America and permanently changing the gendered climate of American politics. Ferraro has been widely acknowledged as having paved the way for future generations of female politicians.

Originally from New York, Ferraro worked as a public school teacher before earning a law degree in 1960. Ferraro worked in real estate and did pro bono work for women, and eventually led the Special Victims Bureau of the Queens County District Attorney’s Office, responsible for the prosecution of every case involving sex crimes, domestic violence, and/or child abuse. During the early years of Ferraro’s legal career, Ferraro and her husband, John Zaccaro, had three children and worked to balance their personal and professional lives.

Ferarro was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives as a Democrat in 1978 and then reelected in 1980 and 1982. In the House, she worked in support of the Equal Rights Amendment and the Women’s Economic Equity Act. As the child of an Italian immigrant, Ferraro’s support of pro-choice policies caused major tensions within Italian Catholic communities. In the 1984 presidential election, Mondale and Ferraro lost to Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush. After the election, the House Ethics Committee announced that Ferraro and Zaccaro had misreported important financial information. Many supporters have claimed that the degree of scrutiny to which Ferraro was subjected was based largely on Ferraro’s gender.

Ferraro campaigned unsuccessfully for a New York Senate seat in 1992 and again in 1998. Between these campaigns, President Bill Clinton appointed Ferraro as a United States Ambassador for the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, a position Ferraro occupied for four years. In 1994, Ferraro was elected into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. Following a 1998 cancer diagnosis, Ferraro became an outspoken advocate on the disease. In 2008, Ferraro worked on Senator Hillary Clinton’s 2008 presidential campaign against Senator Barack Obama, during which Ferraro took heat from supporters and opponents alike for making comments that some deemed to be racist. When Governor Sarah Palin received the Republican nomination for vice president in the 2008 election, Palin became the first woman since Ferraro to be nominated by a major political party for vice president.

Over the years, Ferraro published many articles and authored multiple popular books, including My Story in 1985 and Changing History: Women, Power, and Politics in 1993. In 2014, Geraldine Ferraro: Paving the Way, a feature documentary about Ferraro’s life and career, premiered on Showtime in honor of Women’s History Month.

Viki Peer

Ferraro, Geraldine. 1993. Changing History: Women, Power, and Politics. Wakefield, RI: Moyer Bell.

Geraldine Ferraro: Paving the Way. 2014. “Geraldine Ferraro: Paving the Way.” http://www.ferraropavingtheway.com.

History, Art and Archives: United States House of Representatives. n.d. “Ferraro, Geraldine Anne.” http://www.history.house.gov/People/Detail/13081.

Queens District Attorney’s Office. 2014. “Special Victims Bureau.” http://www.queensda.org/specialvictims.html.

Rosie the Riveter lingers in the American imagination as a symbol of the fresh-faced bravery, patriotism, and selflessness of the American women who gamely stepped into manufacturing jobs vacated by new soldiers after the United States entered World War II. Beyond her context in WWII history, Rosie the Riveter has persisted as a feminist icon, a sign of women’s workplace liberation, and a metaphor for American women’s participation in the nation as citizens and workers.

The iconic “We Can Do It!” poster featuring the image of Rosie the Riveter sporting a red and white polka dot bandana and rolling up her blue uniform sleeve was created by J. Howard Miller for Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company in late 1942. Norman Rockwell also created a Rosie the Riveter for the May 1943 cover of the Saturday Evening Post. Although “We Can Do It!” emerged as the most easily recognizable version of Rosie after the mid-1980s, during the war, Rockwell’s Rosie vastly overshadowed Miller’s. It is likely that the popular tune, “Rosie the Riveter,” sung by Kay Kyser on radios across the nation in 1942, inspired both images. Though remarkably different in their composition, purpose, and style, audiences often conflate the two best-known Rosie the Riveter images. Both have contributed to the mythos of the young, white, female, American war worker.

Despite Rosie the Riveter’s continued cultural position as a feminist icon, her liberation possibilities have been largely exaggerated in the American cultural imagination. Although the advertising and government propaganda campaigns (of which Rosie the Riveter was part) rapidly expanded the parameters of acceptable feminine behavior in response to the dramatically changing needs of the economy, the images of working women did not replace traditional expectations about the sexual division of labor or the limitations of proper femininity. Contrary to popular images, most women did not work as riveters; much higher percentages worked in “pink-collar” jobs as nurses, secretaries, and other female-designated positions. Even at the height of the war, only 37 percent of women worked (McEuen, 2011: 35). Furthermore, Rosie the Riveter imagery obscures the classed and racial reality of women workers. Contrary to popular images, the female workforce consisted largely of working-class wives, widows, divorcees, women of color, and students whose work arose from economic necessity more often than patriotic duty. Both Miller’s and Rockwell’s Rosies are white women. Although women of color were much more likely than their white counterparts to work, they remain absent from mainstream wartime imagery.

This idealized image of the female wartime worker bolstered several facets of the American imagery surrounding the war, particularly in the decades since its conclusion. First, pretty, young, unmarried women war workers were meant to inspire courage among soldiers abroad and to imply that bravery on the battlefield guaranteed soldiers new sweethearts upon their safe return. Related to this message was the metaphor of the woman as the besieged nation. As such, she—and the nation—deserved all citizens’ protection, dedication, and loyalty. Second, the war worker embodied the ideal spirit of the home front: hardworking, stoic, long suffering, and united for victory. Lastly, Rosie the Riveter reminded women that traditionally feminine qualities best equipped them to fulfill their civic and moral responsibilities as citizens. These messages became indelible components of the American ethos, and as such Rosie the Riveter endures as a symbol of American values, women’s liberation, and the Greatest Generation.

Samantha L. Vandermeade

FURTHER READING

Gluck, Sherna Berger. 1987. Rosie the Riveter Revisited: Women, The War, and Social Change. Boston, MA: Twayne Publishers.

Honey, Maureen. 1984. Creating Rosie the Riveter: Class, Gender, and Propaganda during World War II. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

Kimble, James J. 2006. “Visual Rhetoric Representing Rosie the Riveter: Myth and Misconception in J. Howard Miller’s “We Can Do It!” Poster.” Rhetoric & Public Affairs, 9(4): 533–69.

Knaff, Donna B. 2012. Beyond Rosie the Riveter: Women of World War II in American Popular Graphic Art. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press.

McEuen, Melissa A. 2011. Making War, Making Women: Femininity and Duty on the American Home Front, 1941–1945. Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press.

Billie Jean King’s professional tennis career goes hand in hand with her fight for women’s rights. In tennis and in all sports, King has actively worked to ensure women’s rights and, later, LGBT rights. Arguably, her highest profile battle for equality was her 1973 tennis match against Bobby Riggs, dubbed the Battle of the Sexes, which aired on primetime television.

King’s lengthy (1959–1990) tennis career was impressive, with 67 singles titles and 101 doubles titles (WTA, 2016). Her tennis prowess earned her the title of the Sports Illustrated Sportsman [sic] of the Year in 1972, becoming the first-ever female athlete to earn the honor. However, she became arguably even better known and respected for her tireless activism for women’s rights, especially in the world of sports.

On September 20, 1973, King played an exhibition tennis match against Bobby Riggs, a retired top men’s tennis player. King agreed to the match after Riggs’s repeated public statements that women’s tennis was inferior to men’s and that he could beat any of the then-top players despite his age (at the time, Riggs was 53). The Battle of the Sexes match was televised live on ABC, with Howard Cosell calling the high-profile match. It attracted an estimated audience of over 50 million people (Tennis Channel, 2003). King beat Riggs in straight sets, 6–4, 6–3, 6–3. In interviews since the match, King has repeatedly acknowledged that for the advancement of women’s rights, she had to win the match. “ ‘This was about history, getting us on to a more level playing field because of Title IX and the women’s movement, all that was very close to my heart and very important to me,’ ” recalled King (Tennis Channel, 2003). King’s victory, along with the passage of Title IX, are major landmarks in the public acceptance of women in sports.

In the early 1970s, King watched as tennis money increased for the networks and the male players while the female players’ salaries languished. In 1973, just before Wimbledon, King, along with a few other female players, founded the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) in order create one tour for women’s tennis and create a unified voice for more equitable pay. Today, the WTA is the governing body for women’s tennis.

In 1974, King expanded her equal rights activism by founding the Women’s Sports Foundation (WSF). Still active today, the WSF works to ensure women and girls access to sport. In 1981, King became the first professional athlete to publicly identify as a lesbian. She was outed as a result of a lawsuit. The revelation of King’s sexual orientation cost her endorsements, money, and friendships. However, since that time, King has become a spokeswoman for LGBT rights, and in 2009 she earned the Presidential Medal of Freedom for “champion[ing] gender equality issues not only in sports, but in all areas of public life.”

Still a well-respected activist, King has earned many honors, including being named one of the “100 Most Important Americans of the 20th Century” by Life Magazine (1990) and receiving the Arthur Ashe Courage Award (1999). King has been regularly cited as an idol and mentor to many high-profile tennis players, such as Chris Evert, Martina Navratilova, and Venus Williams.

Allison L. Harthcock

See also: Williams, Venus and Serena.

FURTHER READING

King, Billie Jean, and Christine Brennan. 2008. Pressure Is a Privilege: Lessons I’ve Learned from Life and the Battle of the Sexes. New York: LifeTime Media.

Naify, Marsha. 2013. “Billy Jean King.” Lesbian News, 39(2).

“The Tennis Channel to Air Exclusive Event Marking 30th Anniversary of Historic Billie Jean King vs. Bobby Riggs ‘Battle of the Sexes’ Tennis Match.” 2003. September 10. http://tennischannel.com/press_releases/the-tennis-channel-to-air-exclusive-event-marking-30th-anniversary-of-historic-billie-jean-king-vs-bobby-riggs-battle-of-the-sexes-tennis-match-seotember-20-beginning-at-8-p-m-et-2/.

“ ‘You’ve Got to Give People a Spectacle.’ ” 1998. Business Week, 3591: 66.

Angela Y. Davis, who was born in Birmingham, Alabama, is an American activist, writer, scholar, and public speaker. Initially deeply involved in activism regarding both civil rights and communism, Davis continues to dedicate herself to working for social and political rights, with a current focus on the prison system. As a radical black feminist activist who has at times championed black nationalism, Davis is a controversial figure for some, but her revolutionary contributions to feminist theory, prison abolition, and anti-imperialism movements are undeniable.

Davis completed her undergraduate degree in French at Brandeis University, studying under Herbert Marcuse (1898–1979). After studying at the Marxism-based Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt, Germany, with Theodor Adorno (1903–1969), a leading figure in theorizing cultural studies and cultural critique, Davis attended the University of Paris before returning to the United States. She resumed study with Marcuse at the University of California at San Diego, where she earned her master’s degree. She then secured a PhD in philosophy from Humboldt University.

Davis began her academic career at the University of California, Los Angeles, and has also taught at San Francisco State University and the University of California Santa Cruz, where she currently holds the status of distinguished professor emerita in the history of consciousness and feminist studies departments.

In popular culture, Davis may be best known due to her 1970 arrest, subsequent time in prison, and eventual acquittal. During the August 1970 trial of the three men commonly known as the Soledad Brothers, weapons registered in Davis’s name were used during a failed escape attempt. Davis was placed on the FBI’s Most Wanted List and fled; she was eventually captured in New York City and imprisoned in California. A massive, multi-pronged movement for Davis’s release began, raising awareness of her situation among the public, and after 16 months in prison, Davis was eventually released on bail and then acquitted of the charges.

In 1974, Davis published Angela Davis: An Autobiography, which detailed her incarceration and acquittal; The New York Times described it as “exemplary,” and labeled it “an act of political communication” (Langer, 1974). While many of her books and essays draw on autobiographical material, Davis has no other fully autobiographical works; some biographies exist, but none appear to be sanctioned and acknowledged by Davis. The arrest and trial were also examined in a documentary coproduced by Jada Pinkett Smith, Free Angela and All Political Prisoners (2013), which featured interviews with Davis. The film won the NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Documentary. Other tributes and works about her include the Rolling Stones’ song “Sweet Black Angel,” which is dedicated to Davis, and John Lennon’s song “Angela.”

Davis has been a member of a number of organizations working toward social and political change over the years, including the Communist Party USA (primarily as part of the Che-Lumumba Club, an all-black part of the party), the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and the Black Panthers. In 1980 and 1984, Davis ran for vice president of the United States on the Communist Party ticket. More recently, she helped found Critical Resistance, a group focused on prison abolition in the United States; she is also affiliated with an Australian organization that advocates for the rights of women in prison. In addition to her activist work, Davis has published significant scholarly work, including nine books as well as a number of essays and articles. Her work addresses gender, racial, LGBT, and economic inequality, focusing on the relationships between capitalism, imperialism, and inequality. As early as 1971, Davis identified the “judicial system and … the penal system” as “key weapons in the state’s fight to preserve the existing conditions of class domination, therefore racism, poverty, and war” (Davis, 1998: 44). Today, this idea is more generally known as the prison-industrial complex to recognize that the penal system provides mutual profit for government and industry, and is also a means of enforcing racial and social control.

Jessica E. Birch

FURTHER READING

Davis, Angela Y. 1998. The Angela Y. Davis Reader. Edited by Joy James. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

Davis, Angela Y. 2013. Angela Davis: An Autobiography. New York: International Publishers.

Free Angela and All Political Prisoners. Film. Directed by Shola Lynch. Lionsgate, 2013.

Langer, Elinor. 1974. “Autobiography as an Act of Political Communication.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/books/98/03/08/home/davis-autobio.html.

Sally Ride is most widely known as the first American woman astronaut to go into space. In addition to her success as an astronaut, Ride excelled as a tennis player, a scientist, a researcher, an educator, and an advocate for helping young women see their potential in the fields of science and technology.

From an early age, Ride excelled at athletic competition and briefly considered the possibility of becoming a professional tennis player. It was at Stanford University that she decided to refocus her efforts on astrophysics. During her doctoral studies, Ride and 8000 other individuals responded to NASA’s job advertisement for mission specialists. For the first time, NASA explicitly encouraged both minority and female candidates to apply. After enduring grueling interviews and physical and psychological tests, Ride joined the 1978 class of astronauts.

During training, Ride learned to fly T-38 jets and spent hours in a simulator, learning to operate the space shuttle’s robotic arm used for releasing and retrieving satellites. Her skills at manipulating the arm, along with her calm demeanor, earned her a spot on the STS-7 crew. The press was relentless. Reporters asked Ride questions ranging from “How does it feel to be a woman on an otherwise all-male crew?” to the more presumptuous, “Did you ever want to be a boy?” Ride and her crewmates tried to emphasize that gender made little difference in the shuttle and that Ride was chosen because of her qualifications. However, even NASA was uncertain how to accommodate a woman in space. At one point, for instance, NASA officials asked her if 100 tampons would suffice for her seven-day flight. “No. That would not be the right number,” Ride said in response (Sherr, 2014: 145).

Ride proved that women could be successful in space, as she put her many hours of simulation practice to use releasing satellites into orbit. On June 24, 1983, she returned from her first space shuttle mission. However, her work for NASA was far from over. She served on a second shuttle crew in 1984 and played a critical role in the investigations following the deadly 1986 Challenger explosion and 2003 Columbia disaster.

After retiring from NASA in 1987, Ride became a professor at University of California San Diego. She also wrote children’s books and founded Sally Ride Science, an organization intended to support student interest in science and technology. Ride understood that young girls and minorities often could not picture themselves as scientists. Through her books and lectures, Ride shared her experiences, hoping to demonstrate to students and educators that “scientists and engineers are diverse men and women with exciting careers” (Ride, 2009: 21).

Following Ride’s death from pancreatic cancer in 2012, the public learned of her private, long-term relationship with Tam O’Shaughnessy, a woman whom Ride met playing tennis. Though some criticized Ride for not using her fame to further LGBTQ activism, others supported her choice to remain private because of her ties to NASA, a traditionalistic, conservative organization averse to public relations controversies.

Madelyn Tucker Pawlowski

FURTHER READING

Ride, Sally. 2009. “For the First Woman in Space, Science Is the First Frontier for Students’ Dreams.” American School Board Journal, 196: 21.

Sherr, Lynn. 2014. Sally Ride: America’s First Woman in Space. New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks.

Sonia Sotomayor was the first Latina and third woman to be appointed to the United States Supreme Court. As a self-described “Nuyorican” (UC Berkeley News, 2009), growing up in New York with the strong influence of her Puerto Rican–born parents and their cultural traditions, Sotomayor’s identity and activist background came into play during her Supreme Court confirmation hearings. Since joining the Supreme Court in 2009, Sotomayor has often sided with the other justices who are considered liberal leaning in their interpretations of the law.

Sotomayor grew up in public housing in New York and attended Cardinal Spellman High School. She earned her undergraduate degree from Princeton University and her J.D. from Yale Law School. After serving in the District Attorney’s office and in private practice, Sotomayor was nominated to the U.S. District Court by then-president George H. W. Bush. Here, she famously wrote the decision that ended the Major League Baseball strike, siding with the players. The New York Times noted that “she was widely celebrated, at least in those cities with major-league teams, as the savior of baseball” (Stolberg, 2009). Sotomayor then went on to serve on the United States Court of Appeals from 1998 until her nomination to the Supreme Court in 2009.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor is the first judge of Hispanic heritage to be appointed to the Supreme Court of the United States. She was nominated by the first African American president, Barack Obama. (Steve Petteway, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States)

Following her nomination to the Supreme Court by President Barack Obama, Sotomayor was critiqued by conservatives for a statement she made during a speech at the University of California Berkeley School of Law in 2001. Sotomayor, then serving as a federal appeals court judge, addressed gender and ethnicity in the judiciary. She said that “[w]hether born from experience or inherent physiological or cultural differences … our gender and national origins may and will make a difference in our judging.” Conservatives asserted that Sotomayor’s stance appeared to conflict with expectations that a judge should be impartial and objective. Noting that “there can never be a universal definition of wise,” she added, “I would hope that a wise Latina woman with the richness of her experiences would more often than not reach a better conclusion than a white male who hasn’t lived that life” (UC Berkeley News, 2009).

During her confirmation hearing, Sotomayor sought to clarify her comments. She told the Senate Judiciary Committee that her record demonstrated that life experience and personal views do not guide her judgments, adding that judges should “test themselves to identify when their emotions are driving a result, or their experiences are driving a result, and the law is not” (Goldstein, 2009). Her nomination to the Supreme Court was approved in the Senate by a 68–31 vote that broke down largely along party lines.

Supreme Court Justices seldom achieve celebrity status, but Sonia Sotomayor is an exception. Her memoir, My Beloved World, was published in 2013 and topped The New York Times bestseller list. At standing-room-only appearances on her book tour, Sotomayor spoke warmly and openly to audiences about her life and her career. Even the White House accommodated her busy public schedule: the swearing-in ceremony for Vice President Joe Biden’s second term of office, with Justice Sotomayor presiding, was held in the morning instead of the afternoon because of a conflict with her scheduled reading at a Barnes & Noble in Manhattan. She has also appeared on The Daily Show, The Colbert Report, and Sesame Street, in an effort to make the Supreme Court more familiar and accessible.

Linda Levitt

FURTHER READING

Goldstein, Amy, Robert Barnes, and Paul Kane. 2009. “Sotomayor Emphasizes Objectivity, Explains ‘Wise Latina’ Remark.” Washington Post, July 15. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/07/14/AR2009071400992.html.

Sotomayor, Sonia. 2013. My Beloved World. New York: Knopf.

Stolberg, Sheryl Gay. 2009. “Sotomayor, a Trailblazer and a Dreamer.” The New York Times, May 26. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/27/us/politics/27websotomayor.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0&module=ArrowsNav&contentCollection=Politics&action=keypress®ion=FixedLeft&pgtype=article.

UC Berkeley News. “A Latina Judge’s Voice: Judge Sonia Sotomayor’s 2001 Address to the ‘Raising the Bar’ Symposium at the UC Berkeley School of Law.” http://www.berkeley.edu/news/media/releases/2009/05/26_sotomayor.shtml.

Two-time Green Party vice-presidential candidate Winona LaDuke is an internationally renowned scholar and activist best known for her work on Native American rights and environmental issues. LaDuke, an Anishinaabekwe (Ojibwe) enrolled member of the Mississippi Band Anishinaabeg, was born in Los Angeles, California, on August 18, 1959, and raised in Ashland, Oregon. In 1977, 18-year-old LaDuke spoke at the International Non-Governmental Organization Conference on Discrimination Against Indigenous Populations in the Americas, which marked a pivotal moment in the then burgeoning indigenous peoples’ movement. For the first time in history, the United Nations (UN) opened its doors to indigenous delegates who called for a number of stipulations including, but not limited to, the establishment of a UN Working Group on Indigenous Populations. LaDuke’s expert testimony on how the exploitation of natural resources impacts the indigenous peoples of North America set the stage for her continued activism at the intersection of Native American and environmental issues.

After graduating from Harvard University in 1982, she moved to the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota, where she later founded the White Earth Land Recovery Project (WELRP). Dedicated to recovering the original reservation territory—land that belongs to White Earth tribal members—WELRP directs a wide range of community-based programs focusing on cultural conservancy and, in particular, traditional agriculture (LaDuke, 1999: 115–39). LaDuke’s work draws attention to the fact that for Anishinaabeg—indeed, for all indigenous peoples—land is inextricably linked to culture. By restoring local food systems as well as sacred foods (e.g., manoomin, or wild rice), the Anishinaabeg not only preserve and protect this link, they also fight against ecological destruction (LaDuke, 2005: 167–91).

Of particular importance to WELRP’s mission is seed sovereignty, or the right of farmers to cultivate seeds versus the right of corporations to own them. LaDuke frequently speaks out about how native seeds, in addition to heritage crops, contain life as well as indigenous people’s culture, history, and even ancestry. In 2013, she rode horseback along the Enbridge Corporation’s proposed oil pipeline expansion, which would have cut through tribal treaty territory, including the White Earth reservation as well as two wild rice lakes. LaDuke remains at the forefront of this ongoing battle against Enbridge to protect indigenous people’s land and the planet at large from further destruction caused by faulty pipes.

LaDuke likewise connects the violation of indigenous people’s land to the violation of indigenous women’s bodies, further contributing to the scope of environmental justice activism. In an effort to amplify and unite the voices of indigenous women on environmentalism, she established the Indigenous Women’s Network alongside more than 200 indigenous women in 1985. In 1993, she cofounded Honor the Earth with The Indigo Girls (Amy Ray and Emily Saliers) to promote national awareness about Native environmental issues and fundraise for grassroots Native environmental groups. Among the organization’s many groundbreaking initiatives is a campaign to end sexual violence against indigenous women in the Great Lakes region, where natural resource extraction is at an all-time high. For LaDuke, both resource extraction and the alarming rates of sexual violence in extraction zones evidence the enduring legacy of settler colonialism in North America.

LaDuke is a former board member of Greenpeace USA, an international environmental nonprofit organization. In 1994, Time Magazine named her one of America’s 50 most promising leaders under 40 years of age, and in 1997 LaDuke was named Ms. Magazine Woman of the Year for her work with Honor the Earth. She has received many prestigious fellowships and awards, among them the Thomas Merton Award, the BIHA Community Service Award, the Ann Bancroft Award for Women’s Leadership Fellowship, the Reebok Human Rights Award, the Global Green Award, and the International Slow Food Award. In 2007, LaDuke was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame.

Tala Khanmalek

FURTHER READING

LaDuke, Winona. 1999. All Our Relations: Native Struggles for Land and Life. Cambridge, MA: South End Press.

LaDuke, Winona. 2005. Recovering the Sacred: The Power of Naming and Claiming. Cambridge, MA: South End Press.

Nelson, Melissa K., ed. 2008. Original Instructions: Indigenous Teachings for a Sustainable Future. Rochester, VT: Bear and Company.

Notes, Akwesasne, ed. 1978. A Basic Call to Consciousness. Summertown, TN: Native Voices.

Smith, Andrea. 2005. Conquest: Sexual Violence and American Indian Genocide. Cambridge, MA: South End Press.

The women’s liberation movement is a term often used to describe the quest undertaken by American women activists in the 1960s and 1970s to lift women up to a position of social, political, and legal equality with men. Among some feminist activists and historians, however, the term is sometimes used to reference the most radical and anti-patriarchal segments of that movement.

Prior to the 1960s, the opportunities for most American women to chart their own paths in life were circumscribed by cultural traditions and legal restrictions that were deeply entrenched in American society. This state of affairs was generally defended by its male architects, who benefited from their advantageous position in a host of ways. But in the late 1950s and early 1960s a confluence of events and trends laid the foundation for a political and cultural uprising against this male-dominated society. These factors included simmering resentments against a world in which women were expected to willingly accept subordinate roles in marriage and society and make due with employment in a handful of low-wage, traditionally “female” professions. During the economic boom of the 1950s and early 1960s, though, the sheer demand for workers became so great that women were increasingly able to break out of the “homemaker” straitjacket and find jobs outside the home. Women also drew inspiration—and experience in political organizing and activism—from the American Civil Rights Movement.

Even women who managed to gain a foothold in the world outside their homes, though, often found themselves at a disadvantage. Women in the workplace had no legal recourse when confronted with gender discrimination or sexual harassment, and they ran the risk of being fired if they became pregnant. Meanwhile, girls and women who chose to pursue non-traditional dreams still found themselves subjected to harassment, hostility, and ridicule. Women of color had it even worse, typically unable to land jobs beyond the service sector.

The women’s liberation movement of the 1960s and 1970s—sometimes called the second wave of feminism (the first being the original suffragist movement)—emerged in response to this environment of continued inequality. Some of these early activists, such as Betty Friedan and the women who embraced the National Organization for Women (NOW) after its founding in 1966, were primarily interested in pursuing gender equality in American institutions and laws. As NOW itself stated, its goal was “to take action to bring women into full participation in the mainstream of American society, exercising all privileges and responsibilities thereof in true equal partnership with men.” Others had an even more ambitious goal—to completely uproot the patriarchal foundations of American thought and thus “liberate” women to have complete agency over their own lives. These latter activists “popularized the idea that ‘the personal is political’—that women’s political inequality had equally important personal ramifications, encompassing their relationships, sexuality, birth control and abortion, clothing and body image, and roles in marriage, housework, and childcare” (Tavaana, n.d.).

Together, these linked but distinct campaigns had a transformative impact on American society, despite the fact that the relationship between the two wings was often strained. Utilizing everything from court challenges in order to end legally sanctioned gender discrimination in employment, education, high school and college sports, and financial lending to provocative demonstrations that took aim at beauty pageants and bridal fairs, activists registered a series of gains that helped break down many barriers confronting women in the United States. These victories were made possible in large measure because of their success in enlisting public support for their goals. But their quest to pass an Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) that would formally enshrine gender equality in the U.S. Constitution fell short—perhaps because the sense of urgency that drove support for the ERA in the first place diminished as women tallied victories in America’s political, legal, and cultural arenas.

Ann M. Savage

See also: Betty Friedan; Gloria Steinem.

FURTHER READING

Collins, Gail. 2009. When Everything Changed: The Amazing Journey of American Women from 1960 to the Present. New York: Little, Brown.

Echols, Alice. 1989. Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America, 1967–1975. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Freeman, Jo. 1975. The Politics of Women’s Liberation: A Case Study of an Emerging Social Movement and Its Relation to the Policy Process. New York: Longman.

Tavaana. n.d. “The 1960s–1970s American Feminist Movement: Breaking Down Barriers for Women.” Accessed May 8, 2017. https://tavaana.org/en/content/1960s-70s-american-feminist-movement-breaking-down-barriers-women.

VENUS WILLIAMS (1980–) AND SERENA WILLIAMS (1981–)

Venus and Serena Williams have been trendsetters since they entered the professional tennis circuit in 1994 and 1995, respectively. Throughout their lengthy professional careers, they have fought for equal pay and stood up to racism in a largely white sport. In addition to their activism, they have also been innovators off the court. Both have engaged in entrepreneurial and philanthropic endeavors throughout their tennis careers.

Simply by virtue of their presence as African Americans in a largely white sport, the Williams sisters have changed the face of U.S. tennis. Coached by their father, Richard Williams, and playing on public courts in Compton, California, the Williams sisters took a nontraditional path to the professional tennis circuit. Early in their careers, their background was presented as a detriment or disadvantage to the sisters. However, the Williams sisters have dominated the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) for over two decades. Despite or perhaps, in part, because of their domination, the sisters have been subject to racist coverage, depictions, and statements throughout their careers.

Venus Williams has been ranked number one repeatedly, earned 49 singles titles, 22 doubles titles, four Olympic gold medals (one for singles and three for doubles) and has earned over $34 million in career prize money to date, making her the third highest earning woman tennis player (WTA, 2016).

In 2005, Venus Williams met with Wimbledon officials to demand equal pay for women, to no avail. In 2006, Venus published an essay in The Times (London), entitled “Wimbledon has sent me a message: I’m only a second-class champion,” which sparked then–prime minister Tony Blair and several members of Parliament to publicly endorse her position. Later that year, Venus was asked to lead a joint WTA and UNESCO campaign for gender equality in sports. In 2007, Wimbledon gave into public pressure to award equal pay to women. Shortly thereafter, the French Open followed suit. Many people argue that it was Venus’s public pressure during a time of her professional dominance that resulted in this significant shift toward equal rights for women in tennis.

Beyond her on-court accomplishments, Venus is an entrepreneur, starting her own fashion line, Ele11en, and interior design company, V*Starr.

Serena Williams’s professional accomplishments are unparalleled: she has been ranked number one repeatedly, earned 71 singles titles, 23 doubles titles, four Olympic gold medals (one for singles and three for doubles), and has earned over $80 million in career prize money to date, making her the highest earning woman in tennis by over $50 million (WTA, 2016).

Serena’s entrepreneurial endeavors include creating an athletic fashion line designed for Nike; a clothing line for HSN; and, most recently, launching her own clothing line, Aneres. Serena’s philanthropic endeavors include being named a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador in 2011, opening two secondary schools in Kenya, and backing the Equal Justice Initiative, which works to end mass incarceration and challenge racial and economic injustice in the United States.

As competitors, the sisters have faced controversy compounded by racism. At the 2001 Indian Wells Masters tournament in California, Venus withdrew from her semifinal match against her sister. Rumors swirled that their father, Richard, was arranging which sister should win the tournament. After the withdrawal, Serena played Kim Clijsters in the finals the next day. During that match, Serena was booed by the crowd throughout the match and her championship presentation. Venus and her father were booed as they entered the stands to watch Serena’s match. Citing the racist vitriol they faced from the crowd, neither Williams sister played the tournament again until 2015, when Serena returned to Indian Wells. In an essay she wrote for Time Magazine, Serena shared her terrifying experience at the 2001 Indian Wells tournament. Citing the changes in tennis, such as the WTA’s and U.S. Tennis Association’s (USTA) swift and public condemnation of racist and sexist comments from a Russian tennis official, along with her own professional growth and accomplishments, Serena decided it was time to return to Indian Wells. To make her return even more powerful, Serena raffled off the opportunity to stand with her at Indian Wells. All proceeds went to the Equal Justice Initiative.

Allison L. Harthcock

See also: Billy Jean King.

FURTHER READING

Djata, Sundiata A. 2008. Blacks at the Net: Black Achievement in the History of Tennis, Volume 2: Sports and Entertainment. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Williams, Serena. 2015. “I’m Going Back to Indian Wells,” Time Magazine, February 4. http://time.com/3694659/serena-williams-indian-wells/.

Williams, Serena, and Daniel Paisner. 2010. My Life: Queen of the Court. London: Pocket.

Williams, Venus. “Wimbledon Has Sent Me a Message: I’m Only a Second-Class Champion,” The Times (London), June 26, 2006. http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/sport/tennis/article2369985.ece.

Alison Bechdel is a critically acclaimed writer and cartoonist. Her first successful publication, considered a cult classic, was the long-running, witty, and controversial comic strip on lesbian culture called Dykes to Watch Out For (DTWOF). The comic strip, which ran from 1983–2008, appeared in several gay and lesbian newspapers, such as the Chicago Tribune’s WomanNews and Between the Lines, and was later published on the Web.

Considered to be one of the first North American pop culture representations on lesbians, DTWOF offered a comical, yet critical, commentary on topical political issues. Characters discussed contemporary events, including gay pride parades, popular protests, and women’s marches as well as their experiences of love, intimacy, trauma, sexism, and homophobia. Importantly, these topics were regularly debated among a diverse group of characters who came from different racial groups and class backgrounds. Based on their different social locations, each character offered a unique perspective on various political issues. The representation of different identities and intersectional politics (the interconnections of oppression, such as sexism and racism) in DTWOF challenged the stereotypical overgeneralization that categorized lesbian feminists as a monolithic group of white middle-class women. Other works by Bechdel include The New York Times best-selling graphic memoir Fun Home (2006), which chronicles her childhood relationship with her gay father, who committed suicide, and her award-winning companion novel Are You My Mother?, which was published in 2012.

Bechdel is also well known for her development of the so-called Bechdel Test to assess the active presence of women in a work of fiction. Although mainly applied to movies, the test—which was first introduced in Bechdel’s 1985 comic strip entitled “The Rule” from DTWOF—has also been used to assess the representation of women in video games and novels. In order to pass the Bechdel Test three criteria must be satisfied: (1) there must be at least two women; (2) the women must talk to each other; and (3) they must talk about something other than a man. Some variations of the test require that the two women have names and that they talk to each other for at least 60 seconds.

Bechdel credits the idea for the test to her friend Liz Wallace, and therefore the test is also sometimes referred to as the Bechdel-Wallace Test. Other names include the Bechdel Rule and the Mo Movie Measure (the latter is named after the main character in DTWOF). The test gained mainstream popularity in 2009, when feminist cultural critic Anita Sarkeesian referenced “The Rule” in a video on her YouTube channel Feminist Frequency. Although the test is a quick and easy way to gauge the presence of women in fictional works and, as such, has become a standard feminist tool to analyze media, the test does not indicate whether a work has sexist content or not. It is also possible that a fictional work about women or with predominantly female characters can also fail the test. However, the Bechdel Test is useful because it helps point out that the lack of relevant and meaningful roles of women in mainstream media is a systemic issue and reoccurring pattern. Several studies have applied the Bechdel Test to box office movies and found that approximately half of the films fail the test (see Hunt, Ramon, and Proce, 2014; Smith et al., 2014). The Bechdel Test has inspired several other tests, including the Russo Test, which analyzes the representation of LGBTQ characters in fictional work, and the POC (people of color) Test, which examines the development and presence of characters of color in television and movies.

Andie Shabbar

FURTHER READING

Bechdel, Alison. 2001. “Dykes to Watch Out For.” Dykestowatchoutfor.com. http://dykestowatchoutfor.com.

Bechdeltest.com. 2014. “Bechdel Test Movie List”. http://bechdeltest.com.

Hunt, Darnell, Ana-Christina Ramon, and Zachary Proce. 2014. 2014 Hollywood Diversity Report: Making Sense of the Disconnect. California: Ralph J. Bunche Center for African America Studies at UCLA. http://www.bunchecenter.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/2014-Hollywood-Diversity-Report-2-12-14.pdf.

Sarkeesian, Anita. 2009. The Bechdel Test for Women in Movies. Video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bLF6sAAMb4s.

Smith, Stacy, Marc Choueiti, Katherine Pieper, Traci Gillig, Carmen Lee, and Dylan DeLuca. 2016. Inequality in 700 Popular Films: Examining Portrayals of Character Gender, Race, & LGBT Status from 2007 to 2014. Media, Diversity, & Social Change Initiative. California: USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. http://annenberg.usc.edu/pages/~/media/MDSCI/Inequality%20in%20700%20Popular%20Films%208215%20Final%20for%20Posting.ashx.

UNITED STATES V. WINDSOR (2013)

United States v. Windsor is a 2013 decision of the United States Supreme Court that paved the way for the legalization of same-sex marriage two years later in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015). In Windsor, the Supreme Court declared unconstitutional Section 3 of the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which defined marriage for federal purposes as the legal union between one man and one woman. Because of DOMA, same-sex couples that were treated as married under the law of the state where they lived were not treated as married for federal purposes.