FOUR

GILGAMESH

The Struggle for Life

The Epic of Gilgamesh tells of the interactions of humans and gods using a rich imagery that allows for several avenues of interpretation. Segments of this story were first inscribed on Sumerian tablets four thousand years ago. The epic was first written by the Akkadians and it was fully recorded later by the Babylonians in 1200 BCE. It survived in an oral version until the latter half of the nineteenth century CE in the Caucasus. In his book Meetings with Remarkable Men, G. I. Gurdjieff says that his father, a storyteller, knew a version very close to the account told in that mountainous region.1

The epic myth can be approached in several ways. At the literal level, the adventures of Gilgamesh in his search for the secret of immortality attracts audiences for entertainment purposes, but the characters and their interactions also show a sensitivity that leads to metaphorical inquiry, similar to that invited by the creation story in Genesis. The wealth of detail reinforces the themes of the Genesis story and encourages us to broaden our inquiry to many other aspects of higher consciousness. At each level of interpretation—literal, allegorical, hieroglyphic, and esoteric—these myths express opposing forces that underlie our personal struggles for a sense of coherence. When contradictory elements appear they invite a possible synthesis, which Jung called enantiodromia.2

Modern archaeologists have sought traces of an actual Sumerian king who might have been a model for the story, but such excursions into the literal distract from the main value of the story, which lies in its symbolism, not its history. A favorite of modern and ancient audiences alike, the epic invokes a level of detail that is, at first, surprising. Besides revealing something of the wisdom of ancient humans, the epic shows that, in spite of the changed circumstances of civilization, our essential perceptions and concerns about life have changed little, if at all. In recent years there has been a virtual spate of republications and new translations of this epic. For our own study of modern translations we use both Sandars3 and Mitchell,4 the latter which we regard as a sensitive and readable translation, available in English and retaining much of the story’s rich symbolism. It is the responsibility of the individual reader, however, to look at what is available and make the requisite effort to choose an appropriate translation.

An overriding characteristic of this epic is its depiction of gods, whose psychological and spiritual motivations enable insights into human behavior, that are difficult to perceive solely through personal experience. Our limited ability to understand these representations is less about an ignorance of the Sumerian or Babylonian texts than about our hard-to-recognize prejudices against accepting that the gods depicted in stories from an ancient culture could reflect our modern makeup. Wisdom exists, however, where we learn to perceive it and when we can circumvent our habitual attitudes and behaviors.

To understand the myth of Gilgamesh is to experience how these early conceptions of gods, or principles, embody our own most deeply felt impulses, desires, and goals. Approaching the text with an open mind allows us to reflect on the universal nature of humans and the vast complexities within us.

The Meeting of Gilgamesh and Enkidu, and the Two-sided Nature of Being

Gilgamesh, the hero-king, is repeatedly said to be two-thirds god and one-third human. He is physically a fully grown, powerful, and handsome man; however, as becomes apparent, physical growth does not complete a being. Gilgamesh displays one-sided, imbalanced, impulsive behavior that continually causes trouble for the people of his city. Part god he may be, but this does not guarantee objectivity. Clearly gods were not “sacrosanct” beings to the Mesopotamians. The people of the town of Uruk reached a point where they beseeched the great god Anu to rescue them from this mighty king, who is “shepherd of the city, wise, comely, and resolute,” yet “no son is left with his father,” and “His lust leaves no virgin to her lover.”5

To balance Gilgamesh’s one-sidedness, the gods send him Enkidu, a hairy man who lives with the animals. Enkidu is the man who, according to Gilgamesh’s mother, “is the strong comrade, the one who brings help to his friend in need . . . you will love him as a woman and he will never forsake you.”6 Gilgamesh acknowledged his mother’s wisdom and expressed the hope that he would indeed have such a friend and adviser.

The implication here is that one important side of our nature, the side that the epic implies is our “essential” nature and important enough to be called a king, is still fundamentally unruly. We do not generally accept this perception, yet throughout the epic Gilgamesh is shown to represent that vitally important part of us, perhaps through the part created two-thirds god that is visionary and responsible for communicating with the world of the gods. The beings called “gods,” however, are not objects looked to for “worship,” as is the case with God in Western culture, but are aspects of creativity that are necessary for our world.

Humans long for freedom, and this basic desire is abetted by the impulsive, naive parts of our behavior. Such a simple impulse, however, needs a broader perspective, one that includes a sense of responsibility that modifies the impulse. There would seem to be little doubt that this is what the ancient authors were demonstrating for the benefit of their audiences, along with themes of cosmic unity, love, and justice. For modern people, raising such issues may be one of the best ways to encourage us to examine our assumptions about building and sustaining relationships with other human beings.

It is sobering to consider that we give more attention to our modern aspirations—such as money and reputation—and our short-term problems than to such fundamental matters. Given the continuing popularity of this myth, we must find it refreshing to catch a glimpse of the larger, freer world of consciousness. How else might we find the capacity to judge our own impulsive behaviors, which seem both dangerous and attractive?

The epic goes beyond this, however, to show that this “Gilgamesh” side is itself composed of two parts. One of them corresponds with impulsive aggressiveness, but this is countered by a side that is sensitive to far subtler emotions. This early myth, in fact, provides a remarkable counter to modern simplistic ideas of behaviorism that are still invoked today in neurological analyses. It is our view that the sensitivity displayed by Gilgamesh can only with difficulty be attributed to the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, the view endorsed by modern neurology. Clearly, this myth goes beyond the mechanisms of neurology and shines a light on less-recognized behaviors, places where humans need further development. It identifies different expressions of a deeply felt need for individuality, which in some cases manifests as a kind of longing. This need for individuality must find a balance with other sides of our nature, which develop under other influences. Gaining such insights into our character leads to an internal freedom, one that we continually seek today within the cacophony of Western culture.

The myth describes additional routes of realization as alternatives that each of us encounters in the process of “growing up.” All of them may be related to our aims, but the myth makes it clear that perceiving the direction toward the balance we desire requires discrimination that is itself liable to many distracting influences. We rarely find ourselves in a position to weigh their impact on us with any real sympathy or understanding of our actual social and psychological situations. This knowledge is imparted particularly through the character of Enkidu, which has many ramifications.

The Character of Enkidu

In the Gilgamesh epic, the complementary side of the ordinary, natural state is personified by a being named Enkidu, who was created in the literature of Sumer and later subsumed into the Babylonian culture. In the Old Babylonian Gilgamesh text, the most nearly complete text available to us, Anu is said to have heard the prayers of the people and so addressed his wife, Aruru, the Sumerian Ki, who, together with their son Ea, the Sumerian Enki, had been responsible for the creation of humankind. To her he said, “You made him, O Aruru, now create his equal; let it be as like him as his own reflection, his second self, stormy heart for stormy heart. Let them contend together and leave Uruk in quiet.”7 Thus Aruru, with the assistance of her son, created Enkidu, whose name in Sumerian means “the spirit who goes to earth.” This spirit becomes a kind of “alter ego” for the great demigod Gilgamesh.

The introductory pages of the Gilgamesh epic show us a remarkable dramatization of the process through which an equal to Gilgamesh became his “second self.”8 Enkidu is the “wild man” who is tamed by being introduced to the world of the king. However, Enkidu, “the spirit who goes to earth,” needs help from certain individuals to recollect his original spiritual nature. Before Enkidu is able to help Gilgamesh cope with the world of humans, he must be reintroduced to the world of the gods.

Enkidu first meets Shamat, one of the temple priestesses of the sacred Ishtar who, in the course of their own personal honoring of the goddess, gave their bodies in sexual congress to any man who desired them. We encountered Ishtar earlier, in her Sumerian incarnation as Inanna, goddess of love, who is also goddess of war. Shamat, her priestess, despite the potential dangers associated with this fearsome wild man, agrees to accompany a trapper in search of Enkidu. This is for the purpose of subduing him by introducing him to a knowledge of human interaction that will enable him to transcend his wild state. The description of her encounter with Enkidu, and the necessary six days and seven nights of virtually continuous sexual intercourse required to complete his transformation, is plainly and simply told in the narrative. At the end of it the exhausted Enkidu finds that the wild animals that had been his only companions until that moment now flee in terror. He is to them a total stranger. Enkidu awakens to a new sense of himself as a man, one who feels the need for a companion.

Shamat gradually leads Enkidu through civilizing influences. First she takes him among local shepherds, where he is exposed to human food and is instructed to thoroughly clean himself and don human clothing. Shamat then leads the well-groomed and attractive wild man to the city of Ur, to the man who, she tells him, is destined to be his companion. In fact, she has already suggested to Enkidu that he is perhaps equal in might to the great Gilgamesh. Thus the story introduces us through Enkidu to the concept of the difference between the “natural,” as represented by Enkidu, and the “divine,” represented by the demigod Gilgamesh, which are sides that can be found within oneself.

The Foundation of Personality in Gilgamesh and Enkidu

The myth explores an aspect of personality that is not well understood or even acknowledged in modern times. Aruru originally placed Enkidu in the world so that he lived in the wild with the beasts. This early life among animals is clearly an allusion to Enkidu’s instinctive foundations, the taming of which were necessary for him to play his destined role as someone who could balance Gilgamesh’s impulsiveness. In the present world, we do not believe that we can equally trust the two parts of us that we call the “instinctive” and the “intellectual.” Since at least the time of Plato, when rational thinking and clear articulation of those thoughts were given precedence, the intellectual has almost always been assigned preferential treatment, at least as the ideal, in cultured society.

Perhaps a similar kind of prescription is being applied here, with the additional suggestion that taming is a factor of early training. Hence the temple priestess is sought to tame the instinctive part. This prescription is, in fact, repeated three times in the epic’s introduction: first by the father, who advises his trapper son to seek out the temple priestess to help with the marauding Enkidu; later by Gilgamesh, who gives the same advice; and finally by the trapper, who explains to the temple priestess what he wants her to do. She understands and without hesitation accompanies him. The myth then points out that when the wild man learned the “woman’s art” and murmured love to her, the wild beasts with whom he shared his life rejected him. Remember that the reconciliation of opposites allows us to find an internal unity. In this particular instance the reconciliation is achieved through a sexual encounter with a temple priestess, who as a representative of a goddess offers a means to connect with divinity. The unselfishness of the priestess lends an additional transcendent quality to the encounter. This represents the initial preparation of the ordinary self for an awakening of higher consciousness, which in Enkidu’s situation leads to his partnership with the demigod Gilgamesh.

Sexuality is thus explicitly recognized in the myth as a force that needs to be reconciled as a conflicting demand of instinctive, wild impulses toward independence and of intellectual clarity. Such a perception may have been much better appreciated in ancient societies, where the passage of the boy or girl into adolescent manhood or womanhood is marked by initiation ceremonies welcoming and supporting the appearance of sexuality as a vital step in personal growth. Evidence of this concept in modern times still lingers in the meaning we sometimes assign to the word maturity. However, while adolescence is grudgingly recognized as signaling the impending struggle toward individuality, in the context of the disciplinary, even violent, problems that plague modern families and schools, it is today more commonly greeted with apprehension. This represents a realistic awareness of the genuine potential for destructive self-assertion and violence that occurs when sexuality overpowers the mind.

Unfortunately, human development requires both self-assertion and a need for reassurances; during adolescence, sexual development enters the mix, further complicating matters. Thus the emerging need to express individuality is often seen as a threat to parental or elder moral authority. The Gilgamesh myth demonstrates that this problem has been known from early times. When Gilgamesh and Enkidu are preparing to leave Uruk and seek out the Cedar Forest to kill its cruel and powerful guardian, Humbaba, Gilgamesh consults the elders for their opinion as to how to meet this monster. The original intention of the elders to protect and guide individuality toward its mature expression becomes lost in their fear that the two inexperienced friends may be unable to exercise adequate control. Loss of control is linked to fear and anxiety about new demands made by unfamiliar developments, and is not confined to adolescence. Reactions and coping mechanisms are influenced by cultural attitudes.

We may gain further understanding of the early part of the myth if we examine more closely the repeated symbol of the temple priestess. Modern views about sexual intercourse often offer only two possibilities: it is either a vehicle of ultimate pleasure or a serious duty for the generation of children. The myth enables us to realize that any such simplistic interpretation is inadequate. The temple priestess serves to offer a different point of view, one that recognizes a finer quality of being within us, a quality that is neither sybaritic nor procreative, but transcends these merely personal impulses. Achieving this transcendent state may require outside help, as is represented by the priestess.

We may require a more than ordinary sensitivity to our own natures if we are to learn to appreciate these perceptions of the ancients. Previously we mentioned a special aspect of the creation of awareness within ourselves that is related to sexuality but not to either of the modern viewpoints listed above. This special aspect occurs in the Babylonian and Egyptian myths of creation, particularly in the arising of the first Egyptian god, Atum. The myth reinforces the need to find a level of awareness that approaches real individuation, not simply a stronger personality.

The Gilgamesh epic shows that Enkidu requires a force that transcends both the instinctive wild impulse toward independence and the equally strong demand for the reassurance of relationship. The story directs our attention to the awareness that arises in the presence of powerful sexual energies. Modern day Western morality that denies the power of attraction shouldn’t lead one to dismiss its potential for directing us toward the need for higher consciousness. It is the genius of the myth to point out that the unity of being that Enkidu was helped to find through the temple priestess is what conferred upon him the wisdom necessary to play the appropriate role for Gilgamesh.

The Partnership Continues

Throughout the rest of the epic, Enkidu struggles to live up to all that was predicted for him as a friend, adviser, and protector of Gilgamesh. Enkidu enters the city of Uruk, intent on challenging Gilgamesh because the king has been riding roughshod over the people. And so he posts himself outside the marital chamber of a young newlywed girl who was awaiting the king’s arrival, as Gilgamesh intends to satisfy his passion before allowing her to proceed with her wedding night with her new husband. Enkidu challenges the approaching Gilgamesh, preventing his entry to the chamber, and the two huge and powerful men contend in a fierce wrestling match, before Gilgamesh, in his fury, tricks Enkidu, causing him to fall to the ground in front of him. But at this point both men suddenly lose their aggressiveness, and instead of continuing to fight, they embrace one another, leaving the young couple to their marriage. Enkidu then acknowledges that Gilgamesh was indeed superior to himself, and the two become the unique friends that Aruru predicted to Gilgamesh in his dreams.

In some ways it is Enkidu who, perhaps because of his former companionship with the beasts of the field, knows better than Gilgamesh the mysterious part that the gods play in nature, including humans. Later in the story he even reminds Gilgamesh of the need to pay respect to the gods at all levels. Communicating with the gods, however, is a function that Enkidu cannot fulfill. Only Gilgamesh communicates directly with them in their own realm.

But we are getting ahead of ourselves. Together the new partners undertake great adventures. It is Gilgamesh’s wish to build a reputation that will guarantee his fame and immortality—at least in the world of humankind.

The myth seems to be describing in Enkidu what might be considered his “individuality,” a property that in recent years has often been called “personality.” The poetry in myth allows for various interpretations, and our perceptions of Gilgamesh and his alter ego may go well beyond a literal understanding. Myth may help us appreciate that we have no basis for supposing that our intellect or our personality provide access to our truly internal creative natures. Our ability to reason is of vital importance in balancing our impulses, but it isn’t responsible for the words we use in our relations with others, and it doesn’t control the poetry or the music within us.

In Gilgamesh we recognize an essential part of being linked with powers and sensitivities, what we usually call higher, perhaps even magical, values. The myth shows how these two parts of a man, the “natural” and the “divine,” even a man who is two-thirds god, are needed if he is to find a true relationship with his whole nature. In this case the balance is found through the clearly necessary intervention of Enkidu.

Further Illusions in the Land of the Living

As the myth continues, Enkidu guides and advises the naive Gilgamesh, helping him to realize the power of his impulses in the “land of the living,” the home of the immortals.9 Several situations described in detail depict very ancient examples of basic human nature, especially our collective nature. In one example, the friends prepare to venture into the Cedar Forest to kill the monstrous evil called Humbaba, whom Enlil had appointed as the forest’s guardian. The myth goes on to show how Gilgamesh marshaled the energy and enthusiasm of the community to help him and Enkidu find the necessary equipment for their undertaking. The community helps them by taking over the construction of huge weapons and armor that most men could not even lift, let alone manipulate. The community meets to carry out the construction of the weapons that the friends wished for, despite the misgivings of the elders about whether they can successfully undertake such a difficult task.

These elders do not take their responsibilities lightly. They are finally persuaded that the urge for the adventure has its real source in the wishes of Shamash, the great Sumerian and Babylonian god of the sun, not simply in the imaginations of the friends in their search for personal glory. Aruru, the mother of Gilgamesh, also realizes that Gilgamesh is responding to an impulse planted in him by Shamash, and so beseeches the god to personally watch over, bless, and protect both her son and Enkidu, whom she has adopted as a second son. She foresees a need for particular care at night and prays to Shamash that when he is elsewhere he appoints the stars and the moon god Sin to continue the watch. The elders agree that, while Gilgamesh cannot undertake the tasks alone, provided he feels fully protected by his companion Enkidu, who has much better practical knowledge and experience, then they too can add their blessings to this undertaking. They advise Enkidu of their concern and stress that he must truly be the guardian of Gilgamesh until their return from the forest.

True to his word, Shamash does indeed watch their trip of six days to the forest to confront Humbaba. And when the critical moment arrives and the friends are still supporting one another, he shouts to Gilgamesh, who can hear the gods, to act at once and slay the beast (figure 4.1) before he has a chance to make himself invulnerable to them. This they respond to, and after several dramatic moments of hesitation and self-doubt they summon their courage and joint abilities and slay the monster. After beheading Humbaba, they take the remains to show to Enlil.

Following this episode we find that Gilgamesh is now confronted by a suddenly passionate Ishtar, the Sumerian Inanna, who insists that he become her husband. In a rarely perceptive mode, Gilgamesh points out her history with previous lovers, all of whom, when they inevitably fell into disfavor, suffered dire fates. Of course, Ishtar is incensed by having her nature pointed out in this fashion and ascends to heaven in a rage, where she demands that Anu give her the Bull of Heaven so that she can destroy the unfeeling Gilgamesh. She wins her suit, and the bull is duly brought to Uruk, where it wreaks the havoc expected of such a powerful force. In the end, however, the cooperation between Gilgamesh and Enkidu is equal to the task set before them. Instead of succumbing to this terrible force, they gain control of its ferocity and finally kill it. This is a resounding defeat for Ishtar, in which she suffers humiliation to her pride, as well as the horror of the death of the Bull of Heaven (figure 4.2). While at the human level this outcome gives rest and peace to the human participants in the encounter, it resounds in heaven and helps lead to the death of Enkidu, decreed by Ishtar and Enlil as a needful balancing of the power displayed by the partners.

In the end, however, Gilgamesh’s development of his personal will over what we unthinkingly call “nature” makes it clear that Enkidu, in his support of Gilgamesh, could not guarantee the necessary functioning at higher levels. The gods Enlil and Ishtar, for all their own impulsiveness, or even because of it, perceive the self-will and pride that dominates the friends in their accomplishments. As a result, Ishtar decrees that Enkidu must die, forcing an anguished Gilgamesh to realize the truth of the worldly endeavors he believed led to “immortality.” The myth suggests that the path to individuality may be a gauntlet of trials.

Figure 4.1. Cylinder seals of a crowned Gilgamesh with a sword or dagger and an axe-wielding Enkidu slaying the bearded Humbaba.

Figure 4.2. Gilgamesh and Enkidu killing the Bull of Heaven.

As in the Genesis story, the price for this internal awakening may be steep. The death of Enkidu marks a similarity in the meaning of the two tales. For both Gilgamesh and the personifications of Adam in the Genesis story, there is a strong movement of pain associated with their awakening. Enkidu represents a vitally important “second self ” who knows about the external world in a way that Gilgamesh does not, and the two develop a relationship through trust and love. If we view Gilgamesh and Enkidu as two parts of a single individual, this self-love, which is closer perhaps to self-respect, enables the two parts to act as one. The early events in the epic repeatedly show the effectiveness of a relationship governed in this way in the ordinary world. In the difficult situations they encounter, the love and trust the partners share enable them to carry out their purposes and achieve success.

The myth clearly points out, however, that success in the adventure of life is a powerfully attractive force for our egos. The joint achievements of the two friends reinforce their joy in accomplishment and perhaps distract them from their original aims. It finally leads them to an ambition to “conquer,” which results in the disastrous outcome of their life together. In the events that lead up to the death of Enkidu, the myth raises many questions about what may be missing from such relationships with respect to our real needs.

In the end the cutting of the cedars and the killing of Humbaba accomplished nothing. In pursuing their own ambitious adventures, the partners had not even considered the commitment of Enlil to the powers of the natural world for which he was responsible. They sacrificed to Shamash, who could have pleaded their case to the gods, but only after the event. And so Enlil responded by giving their hard-earned booty away, some to the Queen of Hell. The recounting of the adventure ends with a weak recognition of the strength of Gilgamesh, “conqueror of the dreadful blaze; wild bull who plunders the mountain,” accompanied by the wry observation that, “the greater glory is Enki’s!”10 That is, the ambition that led Enkidu and Gilgamesh to such wanton destruction ended with the Queen of Hell, ruler of the dead, as the real winner!

Difficulties of Matching Aspirations with Abilities

The myth is uncompromising in its evaluation of the fruits of self-will and ambition in our lives. These interactions with Enlil and Ishtar expose the consequences of such traits. In their adventures the pride of the two heroes led to excesses of action. Their insensitivity killed the guardian of the mysteries of the Land of the Living. Their pride also destroyed the passions represented by the Bull of Heaven and gave rise to taunts and ridicule. Such emotional forces we underestimate at our peril.

In neglecting their responsibilities to the cosmic dimensions of life and attempting to directly grasp what they perceived as the glories, the heroes turned the glories into their opposites. Forces that at one level are a source of generation and development may at a lower level manifest as a desire for power, which can lead to destruction. The myth makes a clear and strong statement that finding the worth in life requires the resolution of opposites through discrimination, which must be found at a higher level than the level of operation of the heroes themselves.

By involving the gods so inextricably in the misadventures the myth shows that the interaction of opposites occurs at all levels; not only our usual lives, but also our most prized hopes and aspirations. The gods live at a level different from humans, and when Ishtar decrees that one of the two partners must die, it seems not to be a retribution, but an inevitability. Enkidu learns of his fate in a dream. As we saw in Gilgamesh’s dream of Enkidu’s creation, dreams are often used in this myth to illustrate the mysterious nature of the connection between the very different worlds of gods and humans.

With great suffering for both the heroes, Enkidu, so much a part of Gilgamesh’s adventures and ambitions in life, is taken from him. Gilgamesh thereby comes to see that his real wish is not for the great feats he and Enkidu had undertaken, but for another, quite different aspect of existence. Behind his original urge to conquer the unknown, he had failed to see the buried sense of his own incompleteness. In the death of Enkidu, however, he is faced with an intimation of his death, which the creation story in Genesis warns is a necessary part of the knowledge of good and evil.

This new awareness finally leads the weeping Gilgamesh, lamenting the death of his friend, to undertake new, lonely adventures in search of the real meaning of life. “How can I rest, how can I be at peace? Despair is in my heart. What my brother is now, that shall I be when I am dead. Because I am afraid of death I will go as best I can to find Utnapishtim, the Sumerian Ziusudra and the equivalent of the Noah from Genesis, whom they call the Faraway, for he has entered the assembly of the gods.”11 He then departs the city of Uruk and sets out on his quest for one who was once a mortal man like himself, but whom Enlil made immortal and set up in the Mesopotamian paradise to the east in the Garden of the Sun.

Adventures in the remainder of the epic graphically portray the strength of the passions underlying Gilgamesh’s new ambition to win immortality for himself. The myth repeatedly shows, however, that his wish is not matched by a sense of discrimination. Time and again, the habits of his lifetime lead him to try to use power where sensitivity and subtlety are needed. Only at the end is there a suggestion that he attains a perspective that enables him to see that wisdom involves the resolution of forces rather than their conquest.

Gilgamesh’s new struggles resemble those of Odysseus in the course of his homeward voyage. When Gilgamesh finally enters the Garden of the Gods, even Shamash is distressed at his woeful appearance. He notes that, “No mortal man has gone this way before, nor will, as long as the winds drive over the sea.”12 To Gilgamesh he says, “You will never find the life for which you are searching.”13 But Gilgamesh refuses to be discouraged: “Now that I have toiled and strayed so far over the wilderness, am I to sleep, and let the earth cover my head for ever? Let my eyes see the sun until they are dazzled with looking. Although I am no better than a dead man, still let me see the light of the sun.”14 Physical exertion had always accompanied Gilgamesh’s passions, and so despite the warnings and discouragement from the gods, he continues in the only manner he knows.

Siduri, a young woman, maker of wine, whom he encountered early in his new search, summarizes his situation with this question: “If you are that Gilgamesh who seized and killed the Bull of Heaven, who killed the watchman of the cedar forest, who overthrew Humbaba that lived in the forest, and killed the lions in the passes of the mountain, why are your cheeks so starved and why is your face so drawn? Why is despair in your heart and your face like the face of one who has made a long journey? Yes, why is your face burned from heat and cold, and why do you come here wandering over the pastures in search of the wind?”15

This description presents a cruel contrast between what the friends had anticipated in adventures intended to “establish[ed] my name stamped on bricks” and the fate they attracted by the intrusion of their blind ambitions into the realms ruled by Enlil and Ishtar.16 Now Siduri accuses him of the folly of searching for the wind, a power that affects all, but that no one can see! Siduri, too, advises him to give up the search. She reminds him that immortality is only for the gods and that he could rejoice in the many substantial things that life offers. “[F]ill your belly with good things; day and night, night and day, dance and be merry, feast and rejoice . . . for this too is the lot of man.”17 Besides, she points out, to find Utnapishtim he has to cross the ocean containing the Waters of Death, and no one but Shamash does that.

Then, perhaps because she cannot control her admiration for a display of will that takes no notice of personal deprivation and suffering, she admits that down in the woods Gilgamesh might find Urshanabi, the ferryman of Utnapishtim. “With him are the holy things, the things of stone. He is fashioning the serpent prow of the boat.”18

Great willpower does nothing to clarify Gilgamesh’s confusion over the nature of his goal or how to reach it. He immediately seeks out the ferryman, but lacking discrimination, in an impulsive attempt to overpower him, Gilgamesh destroys the holy things. These turn out to be devices that ensure the boat’s ability to carry Urshanabi over the sea and prevent the Waters of Death from touching him and his passengers. However, Urshanabi too supports Gilgamesh’s determination, and so directs him to cut 120 poles, cover them with bitumen, and secure them with ferrules. The two men then launch the boat and travel in three days a journey of a month and fifteen days, to reach the Waters of Death. There Gilgamesh uses the poles one after another to thrust the boat onward without getting his hands wet! When the poles are used up, he strips and holds up his arms and clothing for mast and sail. He thus makes use of the power of the wind to help him, despite the doubts of Siduri and Shamash.

The Power of Discrimination: The Story of the Flood

Gilgamesh’s great efforts bring him across the Waters of Death to the land of Utnapishtim. Utnapishtim sees in Gilgamesh what Siduri saw in him. However, after an initial hesitation, he says to Gilgamesh, “I will reveal to you a mystery, I will tell you a secret of the gods.”19 Then he tells the adventurer the story of the Flood.

The story as told by Utnapishtim is filled with imagery and symbolism rich enough to intrigue the most ambitious of interpreters. Many aspects of it are familiar from repetitions in later Western religious traditions, and parallels with the biblical accounts are striking. We do not review them here. The device of a story within a story is often used in myths to make special points. Two of these seem particularly relevant to our search for a path toward consciousness.

In the first place, we are told that Enlil decided to cause the Flood. This decision makes him sound a little like his great-grandfather Apsu, who threatened to destroy all of creation in order to preserve the conditions for his own comfort. However, Enlil’s decision must be seen differently. It was he who separated the earth from the sky. He is the creative force of the wind that in Genesis is the breath on the waters that creates the new possibilities. His impulsive idea of a flood to cure the world of humankind’s cacophony was more an attempt to return to pre-creation conditions than an intention to destroy existence.

Enlil’s solo venture raises a question: What elements are needed for creation? Ninurta, the god of canals who has his own obvious interest in the life-giving properties of water, points out that Enlil failed to achieve his purpose because he attempted to cause the Flood completely on his own. As Ninurta puts it, not even Enlil could devise without Ea (Enki).

When the Flood is over and the creatures that Utnapishtim saved on his boat have landed safely, even Ishtar celebrates the event with her presence and her jewels. She invites all the gods except Enlil to attend, because “without reflection he brought the flood; he consigned my people to destruction.”20 Enlil’s fury when he learns that a mortal has escaped is mainly due to the frustration of his plans. Thus Ea, instead of destroying Enlil as he destroyed Apsu, finds it necessary only to placate him with a combination of cajolery and persuasion, pointing out that a flood is too terrible a punishment for humans.

It thus appears that in the Flood story we have a purposeful repetition of the idea that real actions at any level require a reconciliation of opposites. The impulsiveness displayed by Gilgamesh bears a remarkable parallel to the impulsiveness of Enlil himself. The fact that Enlil requires the moderating influence of Ea invites us to consider the correspondence between Enkidu and Ea. The intellect and reason that they represent play a role in our ability to perceive higher influences. There is an implication here that in our own search we may discover differences in levels of our being that are related to different understandings represented by head and by heart.

The second aspect of the Flood story that is of particular relevance to our interests concerns Utnapishtim’s ability to hear and act on the impending danger of the Flood through Ea’s whispers to him in a dream. Ea told Enlil that the escape of humankind from his curse was to be blamed on the fact that Utnapishtim had learned of it in a dream! Ea, “because of his oath” to his own creation, had caused the dream.21 But neither does Enlil question the success of Utnapishtim’s survival. Thus Utnapishtim survived that which he should not have, only with the help of Ea.

We have already learned of Ea’s use of words and breath as a kind of magic. Ea whispering in a dream is a metaphor that suggests the wisdom that preserves existence comes from levels on high that are difficult to perceive, a finer order than ordinary existence. Evidently messages from the gods are as difficult to hear and act upon as whispers in a dream. In this dream Ea told Utnapishtim to “tear down your house and build a boat, abandon possessions and look for life, despise worldly goods and save your soul alive.”22

There seems to be little doubt that the secret Utnapishtim mentioned is his ability to hear and act on these words of wisdom. In recognition of this fact, after the Flood is over, when Ea asks the relenting Enlil to take stock and decide what should be done, Enlil recognizes Utnapishtim, who “was a mortal man,” as special.23 Thus he ordains that Utnapishtim and his wife should be granted immortality and “live in the distance at the mouth of the rivers.”24

The story of Utnapishtim seems designed to draw attention to the question of what constitutes real individuality and levels of consciousness. Gilgamesh continually attempts to reaffirm his sense of individuality and purpose through his physical prowess, but to no avail. This is maintained in the story of Utnapishtim and the Flood, which makes clear how difficult it is for one to discriminate between one’s ordinary day-to-day nature and that which is required for higher consciousness. Utnapishtim’s abilities are of the required higher order. His ability to hear the advice of a god constitutes a level of comprehension above what may be considered an individual or ordinary viewpoint. This is a rarely recognized perspective that depends on an entirely new dimension of experience.

Utnapishtim’s special powers of discrimination are concordant with what we earlier called a change in the level of being. The irony expressed by the myth is that Utnapishtim’s ability represents a taste of the wisdom of the eternal for which Gilgamesh seeks, but is totally unprepared to appreciate. The question that it raises for us concerns the personal responsibility we take for the discernment that prepares us to participate in such wisdom.

The final episodes of the epic show how Gilgamesh continues to fail to see what stands in his way. Utnapishtim offers to help him with his wish for an assembly of the gods to whom he can state his case and persuade to grant him eternal life. To obtain this wish, Utnapishtim advises Gilgamesh that he must remain awake for six days and seven nights.

Evidently even the greatest of men, or demigods, needs to remain aware of the demands of the flesh in which they are grounded. Indeed, the demand of Gilgamesh’s body for sleep overcomes his intentions to stay awake, and he falls into slumber almost immediately after Utnapishtim tells him the condition of his request. He is not even aware that he slept until Utnapishtim shows him the evidence! Even his passionate wish for immortality is the wish of only one part of his being.

A final opportunity arises through the intercession of the wife of Utnapishtim, who pities Gilgamesh’s weary state and admires his past efforts. She persuades Utnapishtim to reveal another secret—another mystery of the gods. Utnapishtim tells him about a plant that grows under the water: “it has a prickle like a thorn, like a rose; it will wound your hands, but if you succeed in taking it, then your hands will hold that which restores his lost youth to a man.”25

With his customary superhuman effort, Gilgamesh ties heavy stones to his feet and descends into the deepest channel, where he finds and grasps the plant. After returning to the shore he shows the plant to Urshanabi and dreams of how he will take it back to Uruk and feed it to the old men. When that is done he will finally eat of it himself and have back his lost youth.

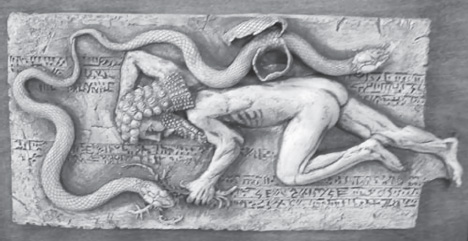

Alas, Gilgamesh at the end displays that he is yet part man, susceptible to spells of irresponsibility. On his way home, his attention is caught by a refreshing pool of cool water. He neglects his stewardship of the precious plant of eternal life for only the few moments required for bathing in the pool, but this is enough for the serpent who dwells in those attractive waters to sense its sweetness, rise up, and snatch it away. As the tale relates, “immediately it sloughed its skin and returned to the well,” stealing the great treasure (figure 4.3 below).26 Gilgamesh laments that through his efforts he had “gained nothing; not I, but the beast of the earth has joy of it now.”27

Figure 4.3. Gilgamesh sleeps while the snake steals the secret flower of eternity. Image courtesy of Neil Dalrymple, www.neildalrymple.com.

An Important Aspect of the Love of the Self

The self-love that psychology and morality alike so often view as a source of selfishness and blindness in our relations with others is certainly an important attribute of personality—one that is not easy to see in oneself. Gilgamesh and Enkidu in their active support of each other often show a kind of self-assured disregard for the sensibilities of other people, and sometimes of gods. The consequences of this are examined later. However, we also need to understand a quite different aspect of self-love that the myth emphasizes—one that is a source of mutual trust and respect between different parts of our natures. In fact, this trust confers on the friends a freedom to undertake their remarkable adventures together.

The myth emphasizes, however, that in the absence of the ability of either of the “partners” to dominate or control the other, their working together depends on the power of attraction that is described as “like the love of a woman.”28 Anu’s original commission to Aruru implies that this attraction may depend partly on the fact that Enkidu was created so much in the image of Gilgamesh himself. However, this doesn’t explain the way they work together. Here, in this power of attraction, the myth shows that development depends on an aspect of love of the Self that has a very different effect than our usual concept of self-love.

The story makes it clear that the love between the parts of our being that these friends represent results in the trust that instinctively and completely supports the very different aspects of their natures in their many demanding and daring adventures. Enkidu is always the trustworthy moderating influence necessary to balance the unruly, adventurous force that is Gilgamesh. He seems to feel equal to almost any challenge. But without Enkidu, Gilgamesh behaves like an unrestrained child, liable to impulsive, even violent and destructive behavior, at the same time lacking the attentiveness provided by a sense of remembering. By contrast, without Gilgamesh, Enkidu’s life lacks direction and a sense of ambition. Neither Gilgamesh nor Enkidu was interested in higher purpose until the gods intervened in their lives.

We can see in Enkidu parallels with Nahash in the Genesis myth. First, both of them represent a wish for a sense of individuality. But in the Gilgamesh myth, through the love they have toward their complementary parts, this wish seems to transcend self-pride or self-assertion. Second, Enkidu and Nahash reflect a concern that their “essential” nature, represented by their partners, Gilgamesh and Adam, should realize its full potential. As a result they act to balance a certain naïveté in the creative impulse to action, which is a necessary step in development. While these actions require participation of the more sensitive, emotional parts, they cannot be undertaken without support from the more substantial, worldly side.

Complementary to the Myth of Gilgamesh as written by the Babylonians in the mid-second millennium BCE, there is recorded on a Sumerian tablet from the third millennium BCE a much earlier story, called Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld, that speaks of the conditions necessary to maintain this trust.29 In this tale Enkidu descends to the underworld to help Gilgamesh recover the (possibly tainted?) gifts given him by Inanna. In his descent, however, Enkidu fails to heed detailed directions and warnings given him by Gilgamesh, who is better informed about this part of the world. As a result, Enkidu dies. Gilgamesh seeks the help of Enlil, who refuses to pay attention to his request. It is then Ea (Enki) who assists Enkidu to re-ascend to his friend. However, by the time this help arrives all that is left of Enkidu is a ghost. The reduction in the power of Enkidu from his descent is a strong reminder of the need for close attention of the two sides for each other. A conscious sense of responsibility for both giving and receiving help is needed. The myth implies that a unity of our sense of being or its capacity for action cannot be sustained by our automatic functioning alone.

The Gilgamesh epic thus portrays an unusual power in a human being—the power to struggle against the forces of nature as well as against the habits formed during life on earth. The hero-king’s aspirations often place him in opposition to the gods. However, this is not so much the result of intentional confrontations as of unintentional consequences of his insistent, indiscriminate exploration of the limits of his abilities.

He does not succumb to the advice that he should act like other men and enjoy the many good things of an ordinary life, such as food, drink, and relationships. He listens instead to his own restless inner nature, and with superhuman but short-lived effort pursues his quest to the very limits of possibility. In the end, he seems to understand that his stubborn insistence on exercising his will is the source of his disappointment.

We can sympathize with the seeming inevitability of the results of his efforts. We too have an inkling of our mortality and our lack of awareness. We can even see our wish for individuality, and sometimes can be helped to realize that we can attain individuality only by seeing and recognizing our failures. Gilgamesh’s return home to carve his story on stone seems to symbolize his eventual understanding that answers to the questions “Who am I?” and “Why am I here?” are not found in adventures abroad, but through patience and contemplation of the strong but elusive powers within oneself.

Whatever the results of his struggles, his remarkable commitment to them set him apart. The myth says, “He was wise, he saw the mysteries and knew secret things, he brought us a tale of the days before the Flood. He went on a long journey, was weary, worn-out with labor, returning he rested, he engraved on a stone the whole story.”30 Gilgamesh’s twisting tale justifies the epithet of the ancients who said, “He was wise!”